Loading...

Issue 42

Woodsmoke and Oranges

British & Irish Music

I want to talk about British and Irish folk music. And I’d like to start with Henry Purcell.

Wait, what?

If you look at the entire history of music, it’s only recently that classical instrumental music became completely separated from folk (and then brought back together with it sometimes in the works of Dvořák, Tchaikovsky, and others). And a thrilling new album demonstrates how, even in the 17th century, good music to dance to was also the best music being composed.

The album is called The Alehouse Sessions (Rubicon Classics), an album of English music played by the Barokksolistene, a Norwegian band led by violinist Bjarte Eike. You might expect a bunch of early-music specialists to give an academically-minded performance. But these guys exist to question the whole concept of what “authentic” really means. To quote the band’s official slogan, “It’s just old pop music.”

What hooked me was a track by Purcell called “Curtain Tune (from Timon of Athens).” Rather than the vertical, almost prim, execution of chords most of us associate with Purcell’s music, Eike and his band play freely and are not afraid to arrange and recompose. In a way, this is not for purists. Then again, who’s to say that an individual interpretation – inspired by the venue, audience, and available instruments – isn’t exactly what Purcell would have thought good and right? This feels like living music.

If you aren’t signed up on Spotify, it’s worth it for the free service that will give you access to this piece:

Not much of The Alehouse Sessions is represented on YouTube, but you’ll get an excellent sense of the freedom of style I’m talking about with this live version of John Playford’s “Wallom Green.” Playford was a generation before Purcell in early 17th-century England, writing dance tunes and music theory texts. If you’ve ever wondered what it was like to set down your beer and lay down some rhythm on the floor of an Elizabethan-era pub, I’m betting it was a lot like this:

Mixed in with acknowledged “classical” composers of the early Baroque, you’ll find traditional folk tunes like the sea chanty “Haul Away Joe” and “Johnny Faa.” And the Alehouse Boys, as the Barokksolistene are currently calling themselves, are about to launch a fall tour in support of the album. Based on the videos I’ve seen and the energy of their sound, witnessing them live would be a rollicking good time.

Another interesting group playing instrumental folk is the Irish band Buille (which means “frenzy” or “madness” in Irish Gaelic). Their new album, Beo (Alive), from Crow Valley Music, proves the quintet to be worth watching. This is newly composed music, but it’s also Irish folk, not to mention a dozen other genres blended together into a unique and satisfying musical experiment.

The opening track, “A Major Minor Victory,” starts out with a boogie-woogie piano bassline played by composer Caoimhín Vallely, and you wonder who kidnapped all the Irish musicians. But then in comes his brother, Niall Vallely, on his concertina (or “box,” as the cool people call it), and suddenly it’s a high-steppin’ reel. And then it’s a jazz number. Then a jazz number and reel mash-up! Why does this work? Who knows, but it does:

“The 1st of August” is a minor-key reel on concertina accompanied by syncopated rhythm from bodhran (drum), guitar, and piano that gives it a jaunty energy. The accentuation of weak beats in reels is reminiscent of the great Bothy Band, a group that helped established how Irish music should be played for worldwide consumption in the 1970s. The reel (in 2/2 time) opens out into a jig (6/8 time), and then Coaimhín’s piano takes over for a while. Tradition meets composition again.

Buille, for all its innovation, is a pub band. That’s a compliment. Their performances offer no frills beyond the music, and their recordings are a true, unadorned representation of what they sound like in performance.

Which brings me to Natalie MacMaster and Donnell Leahy and their recent album, One. Yes, it has lots of energy. Yes, these two master fiddlers (a husband and wife team of Canadian Celts) have incredible chops. But wow, the record is one slick production, and to this particular folkie, that’s not a compliment.

“The Chase” is a good example of this slickness. Irish meets Scottish meets American country meets Vivaldi in this impressive track, but the playing is so tight, and the high frequencies so accentuated, that the track gleams like it’s made of polished steel. If I can’t imagine dirty wooden floors and the smell of Jameson whiskey, I get very suspicious of a “folk” album:

“The Chase”

I don’t need my British and Irish instrumental music to be utterly pure. I just need it to be real.

Dippermouth

January 1, 1901 was a Tuesday in steamy New Orleans. There were folks, mostly muttering vagrants and journalists, who would say it was Wednesday in China, but these people were considered unbalanced and irrelevant. That Tuesday introduced an un-conjoined rabble of miscreants labeled ‘Americans’ into a century that would thrill, fly, drive, destroy and generally scare the crap out of millions of people.

50 years earlier an industrial revolution got kicked off as the necessity of war created new ideas that forever enhanced the colorful pastoral landscape of America. Railroads created new towns across the land as well as a small class of wealthy people. The need of lubricants for these colossal engines created millions of jobs and big holes and a small class of wealthy people. Suddenly horses and trains weren’t fast enough so the two were combined. And the need for a compound that had been being developed for a few centuries without any clear need created a rubber tire industry and a small class of wealthy people. The need to govern this creeping advancement towards a utopian environment cemented a move from politicians being reluctant rural aristocrats, a move that had been building throughout the 19th century, into the career knuckleheads we re-elect to this day. And of course created a small class of wealthy people.

Anyone who owns a home knows that any small crevice, a corner on the underside of your deck or eaves, the spaces between the shingles on your roof and the roof itself, those pesky fence post corners, are irresistible havens for wasps. You create this environment and you have to live with the varmints. Nasty, pesty creatures that have no gratitude that you built this environment and have given them endless opportunities to make your life miserable. So in came the bankers. And another small class of wealthy people. Note: I did not capitalize wasps.

Farming as a way of life was waning, certainly as a small family farm. And this was no more apparent than in the southern United States at the beginning of the 20th century. The carpetbaggers that flocked to the South at the end of the Civil War squeezed the last of any possible revenue from the rural farms and plantations then flocked back north. Whites and Blacks alike went to the cities searching for new jobs and new lives and mostly re-discovered poverty.

Louis Daniel Armstrong was brought into this stew on a Friday. August 4, 1901. He posited his whole life he was born on the Fourth of July 1900, but that’s been discounted because July 4, 1900 was a Tuesday and we have it on solid authority Louis was born on a Friday. He was born into poetic circumstances. Both parents were teenagers, and his mom Mayann brought little Louis into the world in Boutte, a small Creole town north of New Orleans. Pops left when Louis was young, and Mayann was forced to make a decision. Work the sugar cane fields around Boutte, an incredibly hard and dangerous profession, or move to New Orleans and get work as a domestic servant.

Mayann chose the latter. Louis spent the first 5 or so years in the care of his grandmother. Mayann supplemented the wealth she no doubt made as a domestic servant with evenings walking the streets. Picking sugar cane as a job has a nasty and dangerous reputation but choosing prostitution in turn of that century New Orleans in a neighborhood called ‘the battlefield’ over picking cane gives that shit a new perspective.

At 6 or 7 Louis was befriended by a local Jewish family named Karnofsky. He was impressed early on by three things: This family was white and as oppressed as his family because they were Jews, they gave him jobs working their junk business despite the fact they were poor themselves, and they had music. The house was full of singing, and later in life Louis remembered the sounds of the mother starting a lullaby, and the family joining in before going to bed.

The Karnofsky’s scraped together $5, a sum of princes at that time and place, and bought Louis his first cornet. Even at 9 years old he knew what he wanted to do with that thing, and spent evenings wandering around New Orleans listening to music. At the time you could walk the residential streets of this musical city and hear variant styles of music coming from the houses on each block, jug bands, ragtime on player pianos, strings with horns, old men on porches with banjos. But what really drew young Armstrong’s attention was a musical form that was taking ragtime, adding call and answer figures and syncopation that would by the time he was a teenager develop into Dixieland or Creole Jazz.

When Louis was 10 or 11 he really started listening to Joe Oliver and Sidney Bechet. He followed them after gigs, pestered them for lessons and tips on playing. Oliver in particular remembers this little kid they called Dippermouth as talented but really too young to pay much attention to. But even at 11 Louis could make money singing in the streets.

The entertainment environment in New Orleans in 1912 was as rich as it is today. The city was a major route entry for ships, sailors, scoundrels and thieves who needed brothels, drink, and music. A style of singing sprang up with street bands who sang on corners and in front of bars for spare change. They developed a style of imitating instruments with their voices and added growls, howls, and guttural screeches that became known as ‘spasm music’. These spasm bands would do hits of the day for money, adding a new and exciting flavor that couldn’t be called nuance as much as hot sauce. It was fun to watch, fun to listen to, and fun to perform. Louis learned his singing chops in these roving bands of delinquents.

But delinquents they were, and at 12 Louis was arrested for disturbing the peace and sent to the Colored Waifs Home for Boys.

The home was a structured environment where you got three hots and a cot, but were expected to go to school, fix your own clothing, and follow rules. Armstrong was OK with the former but had to be shown that whole ‘rules’ thing that resulted in sore body parts. But the Waifs Home had something he couldn’t resist, and would put up with anything to participate in. They had a band.

Not only did they have a band, but they had a leader, a teacher who would recognize the talent of Louis and would set to bringing this wild kid into a world he would need that discipline to survive. Even late in life Armstrong would credit Peter Davis with setting him on a path that would change his life and the lives of musicians around the world, but remained convinced Davis never liked him. Peter Davis was a hard master and kept Louis in menial roles until he stopped getting into trouble. Louis was first allowed into the band as the tambourine player, which Armstrong considered demeaning and some form of punishment, but Davis would recount he did that to give the boy the rhythm he needed to really succeed on that cornet. Thank you Mr. Davis. Tell us where we can send flowers.

The band introduced Armstrong to structure, discipline and theory, but also to many different styles of music. Ragtime was considered low class and certainly Dixieland hadn’t been explored yet, so Davis taught the boys the popular tunes of the day. Louis never lost the love for different styles, even pop styles, and despite being credited as instrumental in the development of Jazz never considered himself a ‘jazz’ trumpeter. He was an entertainer. And the growling he took from spasm band singing and the natural talent he had for innovation found fertile ground under the shadow of Peter Davis.

The Waif’s Home Band would march in neighborhoods and do concerts. He would remember his entire life the pride he felt going back to the battlefield where the hookers and hustlers remembered Dippermouth and were amazed at his talent.

Upon leaving the home he was a musician for life and went in search for where he would fit best. Ragtime was still popular but had a constriction which chafed musicians like Armstrong. They started playing around the melody, and brought in call-and-answer blues senses into ways to have the instruments ‘talk’ to each other. And it begins.

Armstrong played around New Orleans with several bands, even taking Joe Oliver’s place in a band when he moved to Chicago. But the real next jump was joining a band led by an African American pianist named Fate Marble. At 18 he was playing with Marble on a riverboat band whose captain loved this new ‘jazz’ music that band was playing. Marble recognized Armstrong’s raw talent and knew throwing him into a band with veteran talent would help him. Louis not only learned a new level of music discipline including sight reading charts, he learned he had a natural ability to hear a song once and own it.

In 1922 Joe ‘King’ Oliver called Louis and asked him to join his band in Chicago. Armstrong was 21. The next decade would see Louis revolutionizing the cornet and singing as a jazz instrument. In 1924 he joined Fletcher Henderson’s orchestra, but Fletch didn’t dig Louis’s singing voice and feared that growling would offend his audiences. Armstrong left sending the remainder of the Roaring 20’s with his Hot Five and Hot Seven groups. In 1928 he finally switched to trumpet and in 1930 moved to New York.

Here is Louis’s first solo with King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, 1923, Jelly Roll Morton’s Froggie Moore.

1928, with the Hot Five. A song that follow him his whole life, Basin Street Blues. His power as a player and singer is really taking off. And man, that scat.

In 1937, Louis with the Mills Brothers. Acoustic guitar and trumpet, two instruments only. Mills Brothers vocalizing the horn parts.

Killer.

Bonus. La Vie en Rose. This is much later, like 1950.

Shiver Me Timbers.

Next issue: Louis Armstrong, Ol’ Satchmo. The really amazing later years.

CEDIA

The Custom Electronic Design and Installation Association — better known as CEDIA — holds an annual show for audio/video installers and custom home integrators. It’s a great place to learn about custom home theater and home automation. I attended from the point of view of an audiophile.

This year and next, the show is located at the fabulous San Diego Convention Center on the San Diego bayfront. The location couldn’t be better, and the weather was perfect. Shown on the dining patio of the Convention center is Paul Marble, a friend and fellow member of the San Diego Music and Audio Guild. The Coronado Bridge is in the background.

There were many attractive speakers of interest to audiophiles. To me, this one from Triad was the most elegant.

There were many attractive speakers of interest to audiophiles. To me, this one from Triad was the most elegant. Much of the convention floor was covered with these modular audio/video booths. All of them had great video .... and audio that was too loud. The Starke Sound booth and the Harman booth seemed to be tied for the least fatiguing sound at those elevated sound levels. I was fascinated by Starke's new class A power amp. It comes in various configurations.

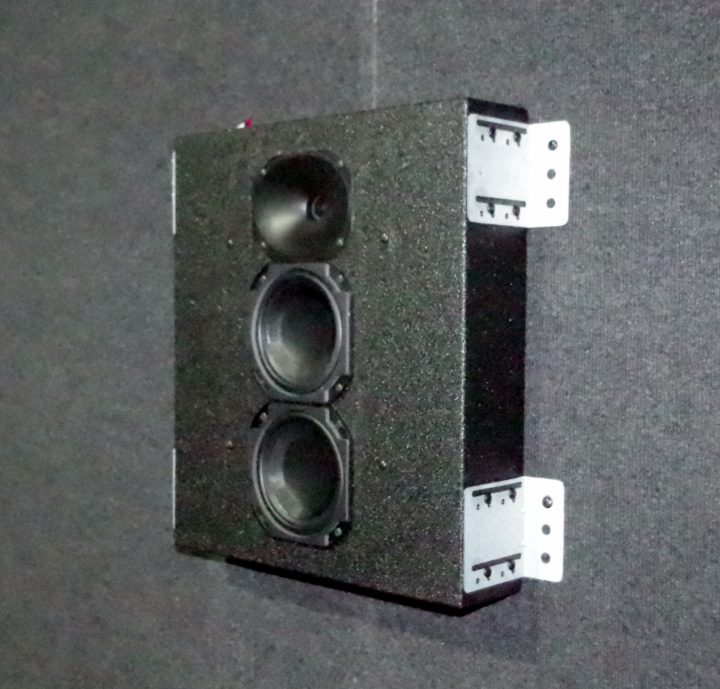

Much of the convention floor was covered with these modular audio/video booths. All of them had great video .... and audio that was too loud. The Starke Sound booth and the Harman booth seemed to be tied for the least fatiguing sound at those elevated sound levels. I was fascinated by Starke's new class A power amp. It comes in various configurations. These (normally) in-wall modules from Klipsch exhibited impressive dynamics and bandwidth at a very reasonable price.

These (normally) in-wall modules from Klipsch exhibited impressive dynamics and bandwidth at a very reasonable price. Nice to see venerable old names revived; this time around, Adcom is a Taiwanese concern. This 200 watt X 5 channel amp retails for $3000.

Nice to see venerable old names revived; this time around, Adcom is a Taiwanese concern. This 200 watt X 5 channel amp retails for $3000. SAE, another venerable name resurrected. Lots of interest in their open-air demos.

SAE, another venerable name resurrected. Lots of interest in their open-air demos. Yes, 6K. This is the first I've heard of it.

Yes, 6K. This is the first I've heard of it. It was just a static display, but the new B & O speakers drew a lot of interest.

It was just a static display, but the new B & O speakers drew a lot of interest. Yes, even your Airstream can be outfitted with an audio/video system.

Yes, even your Airstream can be outfitted with an audio/video system. MBL's sound varies dramatically according to the acoustics of the room. They are using some interesting sound traps here.

MBL's sound varies dramatically according to the acoustics of the room. They are using some interesting sound traps here. For those seeking the sound insulating qualities of double-walled construction without the expense, Kinetics Noise Control has an answer.

For those seeking the sound insulating qualities of double-walled construction without the expense, Kinetics Noise Control has an answer. This screen from Peerless was drenched in water during the entire show.

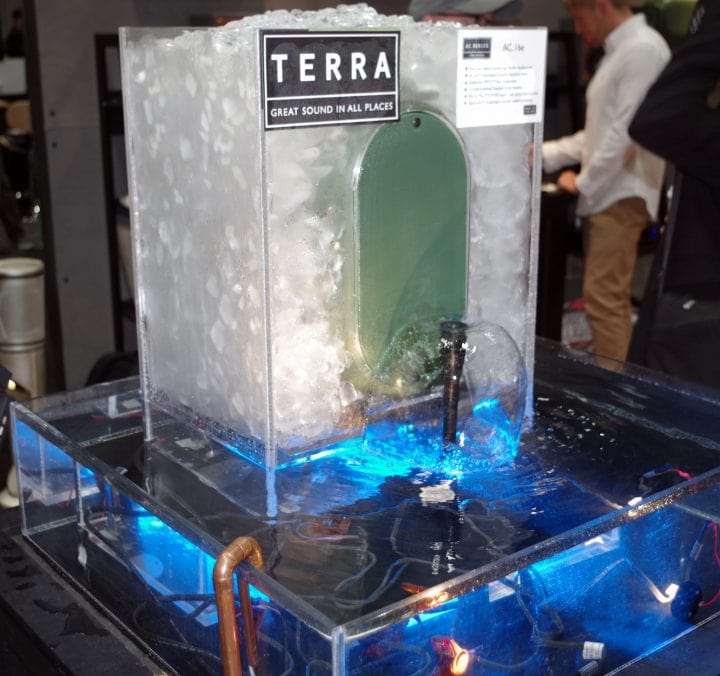

This screen from Peerless was drenched in water during the entire show. These outdoor speakers from Terra played beautifully while exposed to both water and ice.

These outdoor speakers from Terra played beautifully while exposed to both water and ice. Portable sound?

Portable sound? KEF had one of the most attractive displays at the show.

KEF had one of the most attractive displays at the show. Their new, powered, wireless, LS50Ws were very impressive.

Their new, powered, wireless, LS50Ws were very impressive. I particularly liked this screen, though I can't remember why.

I particularly liked this screen, though I can't remember why.

Massive Layoffs at Harman Pro

Back in Copper #27, we reported legal woes at Samsung and made mention of that company’s purchase of Harman International. As is to be expected when any company is sold to a monolith like Samsung, things are changing at Harman. And the news isn’t great for employees at a number of Harman Pro facilities: 650 employees will lose their jobs.

Just to recap: Harman International was the corporate culmination of companies founded and bought by the late Sidney Harman, starting with Harman-Kardon, founded in 1953 by Harman and his partner, fellow Bogen engineer Bernard Kardon. Through the years, Harman International became a powerhouse in three areas: home audio, including brands like JBL, Mark Levinson, Revel, Infinity, and of course Harman-Kardon; pro audio, including brands like Crown, AKG, and Studer; and car audio/electronics, including brands like Becker and the auto-sound divisions of B&O, Infinity, Mark Levinson, and many others.

The home audio division of Harman, with which most audiophiles are familiar, is actually the smallest of the three sectors, averaging about 10-12% of the company’s revenues. Pro sound is roughly double that, with the remaining 60-65% coming from the automotive division. The 2016 annual report showed the company’s revenues at just under $7B; Samsung’s purchase price of Harman was reportedly $8B in cash.

Of the companies affected by layoffs, the one most familiar to audiophiles is undoubtedly Crown. Local media in Elkhart, Indiana, report that the Crown plant will shut its doors, and 115 workers will lose their jobs. An earlier layoff last year laid off 125.

As is often the case, Harman has not issued a press-release announcing the layoff. The most detailed coverage to date has appeared on the AVNetwork; the most interesting part of that coverage is the comments left by audio industry integrators and installers, who clearly have felt let down by Harman many times in the past.

Value For Money?

Upgrading your Hi-Fi equipment can be both deeply satisfying, and deeply unsatisfactory, and both at the same time. Satisfying, because you have invested in something that you have either wanted for a long time, or have spent a long time researching and preparing for. Unsatisfying, because, so many times, after the thrill of the chase is over, and the new car smell has worn off, you often find that your new installation is somehow not much more musically satisfying than the previous system. Go on – admit it. We’ve all been there.

There are many reasons and causes for this, but I am going to focus on two of them that I see happening more frequently than any other – the loudspeaker fixation, and cable allergy. And, more so than with anything I have written so far for Copper, many of you are going to want to disagree fundamentally with me. But stick with me, and hear me out.

It is perhaps natural to focus on the loudspeaker as the ‘most important’ item in your playback chain. Very clearly, different loudspeakers have an immediately obvious different sound signature. Most people, whether card-carrying audiophile or civilian, would agree that they can hear differences in sound when you change from one loudspeaker to another. It is relatively easy for a retailer to hook a bunch of loudspeakers up to a switching box and have the customer switch back and forth between them in real time, with the differences between each model standing in stark contrast. It is not so easy to set this up for a bunch of amplifiers, even less so for a bunch of speaker cables. [I have actually heard it done with amplifiers – and the sonic differences were quite dramatic. It wasn’t all that different from switching between loudspeakers.]

However, differences in sound, and differences in musicality, are different things. It is an inconvenient truth that while anybody can readily appreciate the former, for most people it appears that the latter has to be learned. This is a bit of an uncomfortable assertion, in that it speaks to all sorts of connotations such as ‘golden ears’, ‘trained musician’, and other faintly elitist notions. But it is nonetheless generally the case, and is perhaps a subject for a column all of its own one of these days. It used to be that this learning process was something a good dealer would be able to train you to do. [This was something Ivor Tiefenbrun, the larger-than-life founder of Linn, drilled mercilessly into all of his dealers back in the day.] Too few dealerships these days seem to have mastered that art. In my case, I was shown the light by an infinitely patient salesman in a high-end London audio store during the course of a quiet Tuesday afternoon. What I learned that afternoon shaped the rest of my life.

Most people who are not audiophiles – and many who are – would tend, maybe at least in part subconsciously, to categorize audio equipment into two groups. Those that sound different, and those that don’t. For example, most will happily put loudspeakers into the ‘those that do’ category, and cables into ‘those that don’t’. Amplifiers are usually described by audiophiles as being among ‘those that do’, although real-world behavior tends to suggest that these same people actually treat them more as ‘those that don’t’. The easiest way to quantify this behavior is to consider the way people apportion their budgets in building an audio system. It makes sense that individuals would apportion the money they spend in the way that best reflects their own perception of where the most bang can be had for the buck. Most people – audiophile or otherwise – seem comfortable with the notion that a full 50% of the budget for an audio system should be set aside for the loudspeakers, a ‘those that do’ staple. It is my view that this is seldom the most satisfactory proportion, but there are others who notably disagree.

So, given that loudspeakers indisputably sound more immediately different than do amplifiers, how does an audiophile set about choosing the right pair? The best way to think about different loudspeaker systems is to recognize that each different model has a ‘character’ of sound that is immediately evident, and a ‘quality’ of sound that is not. The elements of ‘character’ are often expressed in terms of a loudspeaker being more or less suitable for one genre of music or another. And it’s true. Some speakers definitely make a better job of pop/rock than classical, and vice versa, and yet others come into their own with intimate jazz. Choosing a ‘character’ that suits you is for many people the major consideration when choosing loudspeakers … and who is to say that’s wrong. But it shouldn’t be to the exclusion of considerations of ‘quality’, the assessment of which is an acquired skill. Don’t go buying expensive audio equipment until you’ve acquired at least a rudimentary understanding of qualitative assessment. If I may make a suggestion, take some time out to go listen to a pair of Wilson’s entry-level (but still car-priced) Sabrinas. These loudspeakers are widely available, and are all about sound quality. The ‘character’ might or might not be to your taste (it’s not to mine, for example), but the ‘quality‘ is indisputable, and is there in spades for you to contemplate. And Wilson dealerships are usually very friendly places.

So the process of buying a system usually starts with choosing a loudspeaker that works well with the sort of program material you like to listen to. And that’s not a bad place to start … but don’t make it both the start and the end. By choosing your loudspeakers you have not broken the back of the task. The key to musical fulfillment lies in what comes next. You should plan to spend equal amounts of time first on loudspeakers, then on source components, then amplifiers, and finally cabling (preferably in that sequence), working with only one category at a time, and in each case following the same procedures and evaluation criteria. There is a solid argument for apportioning costs in the same way as well. Many people have a real problem spending as much on a suite of cables as they do on a pair of loudspeakers or amplifiers – and I can sympathize enormously with that – but if you are serious about buying your system based entirely on what you hear, then that is something to which you should be prepared to give equally serious consideration. I would at least start out with that as your initial objective, and only adjust according to where your auditioning takes you if one aspect or another is proving to be a roadblock.

I want to emphasize this point by focusing on cables during the second half of this column. No other audiophile topic is capable of arousing passions as inflamed as those aroused by cables. Try saying nice things on-line about a set of $20,000 cables and you will be flamed until Christmas. Nonetheless, the effects of cables – power cords, interconnects, USB cables, speaker cables, etc. – on an audio system never ceases to floor me. Like almost everybody else, I guess I have an inherent resistance to accepting the perceived value of (for example) a pair of speaker cables as being remotely comparable to the loudspeakers to which they are connected. But I must also disclose that my B&W 802 Diamond loudspeakers spent nearly a year in a system cabled with a suite of of Transparent Audio Reference cables which sell for more or less the same price as the speakers. And dammit, those Transparents really did make the Diamonds sing! For various reasons I never kept them, and I still wonder whether that was the right decision. The cables are the seasoning on a well-matched system. Get the cables right and the timing and imaging all snap into a clear focus and the sound cleans up quite dramatically. It’s been my experience that the higher up the quality ladder you go in the world of high-end audio, the more important it becomes to get the cables (and other tweaks like furniture and suspension systems) correct.

It is pretty clear that cables incite such strong reactions, is because they offend most people’s sense of value-for-money. Why is that? I think it’s because, since the dawn of the electronic age, anything electronic you bought which needed a cable to function would include a free cable in the box. Shipping a product without a power cord – like shipping a printer without a USB cable – really irks customers who expect these things to be included in the package. I remember the days when every amplifier was shipped with at least one cheap set of general purpose RCA interconnect cables (and a fixed power cord). Consumers therefore have been conditioned to ascribe negligible value to them. What value do you attach to the power cord that came free with your $5,000 amplifier? Not much, I imagine. So how can an after-market power cord be worth $300? Or $1,000? Or even $10,000 for that matter? It is just too easy to dismiss it all as snake oil.

Let’s look at a nice, new, shiny, $10,000 power amplifier. Say something nice about it in a high-end audio forum, and while a few people can be counted upon to be deeply offended by the mere existence of such a product at such a price point, it will mostly be accepted and discussed on its own terms. So I guess we have come to accept that the notion of value-for-money does indeed extend to the $10,000 amplifier. OK, so you go to your nice local dealer and cough up $10,000 for a nice shiny new amplifier. It might surprise you to learn that manufacturer buys all the parts he needs to make that amplifier for less than $2,000. Of that $2,000 in parts, less than $1,000 would be accounted for by resistors, capacitors, transistors, ICs, circuit boards, and the like. The rest goes into the (surprisingly expensive) chassis, the power transformer, the back panel (also remarkably expensive), and the shipping container. Yes indeed, if you knew what you were doing you could build your own $10,000 amplifier in an ugly box for under $1,000.

Now let’s look at an interconnect cable. A cable comprises some wire with a connector at each end. Doesn’t sound like much, does it? If I wanted to make a better-sounding cable, I’d start off by designing a better-sounding wire. Let’s assume that is an easy thing to do (which it most assuredly is not). I’d need to get someone to manufacture my nice new wire, because, like designing my own transistor, it’s not something I can knock together in my basement. I’d need to go to a specialist cable-manufacturing company, of which there are a few out there. These companies do not exist to serve the audio industry. The specialty audio market is just too small to pique their interest. But they’d be happy to manufacture my wire, provided I wanted a couple of miles of it. So alternatively, instead of designing my own special wire, I could just grab their catalog and select an existing wire design whose specs are close enough to what I want.

This was the approach we took to make BitPerfect’s Balanced Interconnect design (now discontinued). The stock wire we specified was priced at about $10 a foot [an even better one was available at $20 a foot!], and I needed four runs of wire per pair of interconnects. A one-meter pair of interconnects would therefore consume about $150 worth of wire alone. Four modestly high quality Neutrik XLR connectors are another $10 each. When you add up everything else that goes into them, one set of one-meter cables costs me well over $200 in parts cost alone. These must sell direct for at least $500 if I am going to make enough profit on them to justify all the development effort. That price will more than double if I am to sell them in a High Street store. Companies who are serious about the cable business will devote considerably more sophisticated design intelligence to their product line than we did at BitPerfect, and their product costs must reflect that.

The people who make after-market cable accessories are not all snake-oil salesmen, even if one or two of them are. They are for the most part highly dedicated individuals and organizations. They make these products because, goddammit, they DO sound better. So much so that a $5,000 amplifier with a $1,000 power cord will almost always sound notably better than a $6,000 amplifier with a stock power cord (all else being equal). A power cord, interconnect cable, loudspeaker cable, or USB cable which is offered for sale at a four-figure – or even a five-figure – price point, may well represent just as good of a deal in value-for-money terms as an equivalent-priced amplifier or loudspeaker, depending on the system into which it is inserted.

If you can get your head around the perceived value-for-money blockage and audition cables the exact same way you auditioned your loudspeakers, source components, and amplifiers, and make the effort to learn how to listen for and recognize the specific contributions cables make to overall system performance, you will be well on your way to buying yourself a system that will deliver a fully satisfying listening experience for a considerable time to come.

Wood

Back in Copper #31, I wrote about the subject of Tone, and how it seems to have vanished as a topic of audio discussions—and really, from consideration as a vital element of audio design. The header pic on that piece was an early Fisher (“THE FISHER”) receiver, replete with a wonderful, warm brassy faceplate and a thick wooden case. Somehow, the appearance of that receiver said “tone” to me—and a major part of that look was wood, plain and simple.

As I’ve mentioned before, my introduction to hi-fi was courtesy of my Uncle Art’s Altec Lagunas, big corner horns which featured large radiused slabs of wood and gently tapered legs, elements that were called “Danish modern” back in the day (nowadays, the generic term for such design elements is Mid-Century Modern or MCM to Craigslist hunters). I still equate warmth of tone with warmth of appearance…and that means wood.

During the early ’70’s when I came of age in audio, the dream speakers of the day meant large expanses of oiled walnut or rosewood. They were designed as attractive elements of a home, not as Frankensteinian outliers bound to be banished to a basement mancave.

I miss that.

Whether it’s due to our Druidic “knock on wood” connection to the material, or just an appreciation of the warm feel of wood, the standard approach to wood is with the hands, as well as the eyes. Not to get all new-agey about it, but I suspect that as more of the things in our lives become ephemeral and virtual, we need a big solid chunk of reality we can lay our hands upon.

Whether it’s as a big ol’ pair of speakers or as a giant, gnarled tree like the one on our back cover—I’m convinced we need wood in our lives.

This B&O receiver displays the company's talent for contrasting beautiful woodgrain with metal. Perhaps if they returned to that formula...?

This B&O receiver displays the company's talent for contrasting beautiful woodgrain with metal. Perhaps if they returned to that formula...? I'm convinced that one of the reasons that the towering Infinity IRS are so appealing is that massive curvy expanse of wood. Kindly ignore the bald spot.

I'm convinced that one of the reasons that the towering Infinity IRS are so appealing is that massive curvy expanse of wood. Kindly ignore the bald spot. Among modern manufacturers, John DeVore clearly understands the appeal of wood. Not surprisingly, his speakers are respecters of tone.

Among modern manufacturers, John DeVore clearly understands the appeal of wood. Not surprisingly, his speakers are respecters of tone.Alice Phoebe Lou

At the ripe old age of 17, Alice Phoebe Lou decided she’d had enough of life in her native South Africa. She slung her guitar across her back and headed for Europe. Everywhere she went, she sang on the street, mainly doing covers of other people’s songs. But then she discovered Berlin and its cutting-edge arts scene. She’d found her home and her creative self.

Lou settled in Berlin and started honing her own songwriting skills. Like many indie musicians, her career is growing fast thanks to word of mouth. Visitors to Berlin come to one of her shows, are bowled over, and take their experience home to share with others. Now Lou can fill venues with over 500 seats when she tours.

She started making home-made CDs as a busker, even designing and printing home-made covers. Now she makes recordings in a studio, emphasizing in interviews how important it is to maintain control over every aspect of her product. “I can’t handle having to answer to anyone,” she claims.

Now 23, Lou has a philosophical depth that belies her age. She has described her songs as having three levels of meaning: a personal meaning for her, a “storytelling aspect,” and a universal human truth. Keep an ear out for exhortations to fight against normalizing hate, one of her most central themes. Individuality is the paramount human right in her view, and anything that threatens the flowering of the individual is an enemy to well-being.

In 2014 she made Momentum, which she calls an EP although it includes eight tracks. The opening song, “Berlin Blues,” is a worthy introduction to her intensely focused voice, tight vibrato, and exact intonation. At first the guitar is the barest framework holding up the tapestry of her singing. Despite the name, “Berlin Blues” is a love song to that city and its attitudes. When the drums come in after the somber intro, Lou sings about freedom – of ideas and intellect, mostly. (You know, typical pop stuff. Ha!) “There is a place…where ideas are for free…and your great mind is no longer the minority.”

In “Grey,” Lou shows off some serious R&B- and jazz-singing chops, spinning out long, melismatic lines that end with a little flourish of vibrato like you might expect from Dianne Reeves. Unlike most of the best-selling artists nowadays, Lou understands that ornaments are just that: decorative elements to hang on the main notes, not a substitute for strong melodic singing. The arrangement is mesmerizing, a combination of percussive synth and electric guitar, provided by Matteo Pavesi:

Pavesi (known simply as Matteo) is the co-star on Lou’s album Live at Grüner Salon. Lou carefully chooses the musicians she works with for their individuality and musical instincts. Besides Pavesi, she also works a lot with producer Jian Kellett Liew (A.K.A. Kyson).

Most of the songs on that live collection have also been released as studio tracks. A stunning exception is “She.” Again, individual freedom is the theme, specifically that of a strong, curious, sexually energetic woman. “She caught a hole in the fence and she ran…she didn’t want to lose her desire.” Lou flips the pitch up to headvoice at the end of each line, giving the song a decidedly African sound, a sensation increased by the repetitive, chant-like simplicity of the melody. Listen to that crowd react with cheers all the way through – these people appreciate what she has to say:

Lou’s debut full-lenghth studio album, Orbit, came out in 2016 on Lou’s own label, Rtbe F-L Groove Attack. Orbit continues to focus on personal freedom, and characters longing for communities without too many rules. “Girl on an Island” has a folkish sound, with parts of the melody reminiscent of Verdi. The lyrics start out telling a story, but end up as more of a lesson: freedom is a state of mind. (The live video offers a great view of the creation of the lilting waltz accompaniment.)

There’s a return to an amorphous jazz style in “Haruki” – I can imagine Billie Holiday just slaying this one. While the text, urging someone to wake up after a long sleep, might be directed at one of Lou’s personal acquaintances, it’s also a warning to all of us that we’ve “forgotten how to live for the now.” This is a good example of Lou’s own theory that her songs can be understood on multiple levels.

Some of Lou’s most intriguing poetic imagery shows up in “Orbit,” the album’s title song, which lilts in a slightly creepy triple time accented with the natural creak of a guitar’s fingerboard. It’s hard to tell whether the opening lines are purely metaphorical or some kind of science-fictional vision. “One foot on the pavement,” she sings, “and one foot in the Milky Way.”

As usual, Lou challenges the listener to pursue a full and meaningful existence: “Do you want to be just a machine in this crazy society?” It’s safe to say that, for her fans, the answer is a jubilant “No!"

Meetings With Remarkable Men, Part 3

In the previous two articles, I wrote about encountering Jack Casady and Phil Lesh as a teenager. Of course, I could write pages and pages about the influence of my father (and my brothers). But there was another person who loomed large in my legend — although we didn’t actually meet until years later. And I’d say this man played a pretty huge role in the lives of Paul McGowan and his pal Gus Skinas, as well.

I’m talking about synthesizer designer Robert A. Moog, of course. Probably nobody of my age can remember where we first heard of the Moog Synthesizer; the name was just in the environment at a certain point. But I know where I first saw one: the Wildwood Convention Hall in Wildwood, NJ in mid-August of 1971. We were there for the day, and we saw that Emerson, Lake and Palmer were playing. My parents paid for my brother and me to go to the show (a whole $4.50 — EACH!), while they went off to the movies (Carnal Knowledge). We’d run into friends down there, and we got seats at the back. Then my friend Glenn and I walked down to the front to look at the gear and…

Oh my god.

I don’t know why it grabbed me so much, but it did. And in those days it was still relatively small. The next day, back home, I got out the Last Whole Earth Catalog, and reread Wendy Carlos’s 2-page spread on synths. And promptly wrote to Robert Moog. (My letter was addressed “Dear R.A…” I was determined to sound as hep and mature as possible — I didn’t want anyone suspecting I was 14!)

I got back a very cordial letter and a 1971 Moog catalog, and a little bit of a correspondence was struck up (along with a daunting price list, showing a list for a large system of $12,500 — two and a half times the price my dad paid for our top of the line Volvo). Gradually, using mostly that catalog, I taught myself to use them. There are certain things that you have to have experience to know, but the broad strokes were all there. I’ll give an example to explain:

The 911 Envelope Generator has 4 controls (three for Time settings, one for the level of sustain). By looking carefully at the photo of an early Moog system, I determined which was the 911 by looking for a module titled with two somewhat lengthy words, and from the description of the module, determined what each of the controls did. Not immediately, of course. I pored over the pictures for months and years, and gradually it came into view, both literally and metaphorically.

Parallel to this, I was slowly piecing together a small collection of electronic music, but most importantly, Carlos’ Sonic Seasonings, a dazzling record of synthesizer and environmental recording, in service to tonal composition. I spent so much time with that catalog that by the time I first got into a lab with a modular Moog in it for a couple hours, I knew what I was doing and put together my first Moog piece. And I went to various colleges that gave me experience on other systems, like EMS and Buchla.

14 years later, I began to fulfill my dream when I acquired the first quarter of of my system (from 1974), and two years later got the remaining 3/4ths of it (from 1967, one of the first systems in California).

These days, they’re available again, and you could buy a system like mine for about $50,000. Like most everything else I have, mine sits unused, except for the occasional museum exhibit.

Not Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting

The popularity of martial arts has grown exponentially in the US in recent years. The sale of the UFC for $4 billion last summer only demonstrates the huge demand for opportunities to both view and participate in competitive combat sports. And aside from the glitz and glamour of televised fight leagues, Americans are flocking to all different types of dojos, academies, and schools to train in the world’s top martial systems.

Although the names and terms that define each style can get confusing, virtually every martial art can find its roots in some ancient practice of war. Whether drawn from the combat styles of dueling tribes or inspired by the weapons fashioned in one geographical region or another, martial arts as we practice them today have been transformed through centuries from their battlefield origins.

Many of the more fluid, dance-oriented martial arts evolved to be that way because oppressed populations and marginalized groups were forced to disguise their martial heritage in order to continue practicing. Distinct geographical boundaries now separate highly detailed difference in style, for example in South East Asia, where in a way, Cambodian, Burmese, Thai, and Malaysian martial arts are unique branches evolving away from the same tree.

In this sense, the way history has unfolded guarantees certain similarities and roots that hold the world of martial arts together more generally. Here we dive into a few of the most popular martial arts practiced in the US today, investigating where each art originated and how its strengths have developed over time. Whether you’re training for fitness, balance, energy, focus, or to climb your way into a fight cage, there’s a martial art out there for you.

When I first found the martial arts academy where I still train today, I knew right away it was the one for me. New York City is filled with pretty gyms and fancy kickboxing classes that focus more on the athleisure styles of the day than actual fight technique, and this works for some people. I was looking for something truer—a martial arts school where I could train like the fighters and learn from the best without having to get my face bashed in. For almost two years now I’ve trained more arts than I could name when I first walked in the door of the school, and low-ranked as I may be, I have no qualms about calling myself a martial artist.

First, what is Kung Fu?

The term Kung Fu is fraught. In today’s American English lexicon, we use Kung Fu to point to Chinese martial arts in general. But in the original Chinese, Kung Fu referred more to the deep study or any kind of profound learning that requires a dedication of energy and time to master. In this sense, your kung fu could be anything, including but not limited to martial arts. Your Kung Fu is whatever you are learning with intensity and dedication at the time towards a goal of mastery, from patience to calligraphy to classical flute.

Karate

Originally developed in Okinawa, Japan, karate has long been known as one of the most commonly practiced martial arts in the US. Pop culture mentions of the art focus mainly on the karate chop, which, regardless of the overuse, does identify karate’s reliance on standup hand striking. Punches and open-handed striking techniques, like the karate chop, are used in karate to both attack an opponent and gain advantage by deflecting and intercepting incoming attacks.

This focus on blocking and reacting to incoming attacks has made karate, at least as it is taught in the US today, an art geared more towards self-defense than combat and competition. On the other hand, karate also employs kicking, knee and elbow strikes which make use of the entire body and prevent a practitioner from relying solely on hand techniques and self-defense strategy. This effort to produce well-rounded karate practitioners also extends to the focus on self-discipline and character development in most karate schools. As a sport, karate is set to make its Olympic debut at the 2020 Summer Games in Tokyo.

Tae Kwon Do

If Karate is the prominent traditional self-defense system from Japan, Tae Kwon Do if often mentioned in the same breath as the sister art from Korea. For over 2,000 years, Tae Kwon Do blends self-defense tactics with punching and kicking attacks to make it a useful and adaptable art in any situation. And where Karate focuses on hand techniques and punching, Tae Kwon Do is most famous for its emphasis on kicks. Traditionally, Tae Kwon Do identifies the leg as the strongest limb in the body, not to mention the furthest reaching.

This basic strategy unites the entire system of Tae Kwon Do around keeping your opponent at a distance, and doing major damage with a well-placed, well-timed, full-force kick. To date, Tae Kwon Do is commonly considered the most widely practiced art in the world. Part of its ease of entry and adaptability comes from the forms that students must learn to progress through the belt rankings. These predetermined sequences of movement incorporate attacking, blocking, placement, and movement technique to demonstrate each student’s progress in the art. Tae Kwon Do and Judo are the only two martial arts currently featured as a sporting event in the Olympic Games.

Judo

Judo was originally developed for sport and physical fitness when it originated in Japan in the late 1800s. Since Judo was not originally created as a fighting style for war, the system grew to encourage throws and takedowns in order to rack up points and eventually win a match. Over the years, judo has evolved into an effective grappling system that works best when in a close quarters environment, say for street fighting or real world self defense situations.

The motto of Judo is widely accepted as “maximum efficiency, minimum effort.” It’s in this way that practitioners learn to manipulate leverage and the natural flow of energy to get the best of their opponents. These concepts paired with techniques and traditional movements make it possible for a Judo practitioner of virtually any size overcome a bigger or stronger opponent.

While there is no direct striking in Judo, punches and kicks are replaced with submissions like chokes and joint locks. In a sport environment, one performs any of these submitting maneuvers until the opponent taps out to prevent serious or permanent injury. In prearranged practice forms called kata, Judo practitioners also incorporate the striking attacks that are otherwise prohibited in competitions.

Brazilian Jiu Jitsu

Although Jiu Jitsu was originally developed in Japan, it is Brazilian Jiu Jitsu in particular that has taken US martial arts schools by storm. The original Japanese sport was designed to enable practitioners to disarm and defend against an attacker carrying a weapon, like a sword or knife. Where Japanese Jiu Jitsu is focused on formalized movements and patterns that can often look very similar to Judo, Brazilian Jiu Jitsu focuses on self-defense and intense ground grappling. Much like Judo, Brazilian Jiu Jitsu is also used to empower smaller practioners to defend against and overcome larger, stronger attackers.

Brazilian Jiu Jitsu is considered by some to be an aggressive, vicious art. Its reputation for choke holds, joint locks, and all-out ground grappling certainly makes the system seem like an intense and dangerous one. But in many of the adaptations of Brazilian Jiu Jitsu that are currently taught in the US, the focus is placed more on strategy and problem solving than ultimate damage to your opponent. Of the hard and soft arts, many consider Brazilian Jiu Jitsu to be a soft art in that it relies on an understanding of the flow of energy between you and your opponent. Manipulating energy and leverage, again, like in Judo, allows for both complex self-defense techniques that are applicable in the real world and competition-ready finishes that employ submissions like locks and chokes to win matches.

Muay Thai

As the name makes clear, Muay Thai originated in Thailand as the nation’s traditional martial art. Also known as the Art of Eight Limbs, muay thai uses punching, kicking, and knee and elbow attacks to round out its arsenal of techniques. In Thailand, children train from extremely young ages to develop and condition their bodies in order to perfectly execute the art. Those viral videos you’ve seen of practitioners kicking palm trees? That was probably some form of Muay Thai in its native Thailand.

Muay Thai can be a very violent sport, in much the same way that traditional Western Boxing often leaves its competitors bloodied and battered. As Muay Thai spreads throughout the US, many American schools teach a style of the art marked by European influence. The traditional Thai stance places body weight heavily on the rear foot and leg, allowing practitioners to launch forward with balance and precision and throw the front kick, known as a teep, to maintain and gauge distance. Dutch influence brings Western Muay Thai closer to our traditional stand-up boxing with a stance that spreads the weight between both feet and keeps a challenger bouncing from one foot to the other in order to gauge distance and plan attacks.

Part of Muay Thai’s popularity in the US can be tied directly to the huge popularity of mixed martial arts or MMA through platforms like the UFC. Many of the sport’s top practitioners through the decades have been highly trained Muay Thai fighters. Between Muay Thai’s reputation as one of the world’s original no holds barred bloody combat sports and the UFC’s Hollywood style, big entertainment treatment of cage fighting, it seems they make a perfect fit to spur on the dominance of martial arts training stateside.

Of course, as it spreads, Muay Thai is also available as a more relaxed training regimen for martial arts students looking to get in a good workout or develop their minds along with their bodies, as opposed to hardcore fight training. Many of the arts that have made their way from the ancient world to the present and from far-flung nations to the US have softened in this way. And thanks to this transformation over time, laypeople like us have the opportunity to learn the arts and philosophies of martial systems from around the world.

Jeet Kune Do

At my martial arts academy in New York, I quickly fell into the world of Jeet Kune Do. Known best as the martial system developed by Bruce Lee before his untimely death in 1973, Jeet Kune Do may be less commonly practiced because the lineage of the art is fiercely protected. And, Lee broke all the rules to develop the ultimate “no way as way” style while training and teaching on the West Coast. Lee traveled the country and the world to train with top-ranked practitioners in a variety of arts, when it was widely considered dishonorable to train at a school other than your own home dojo.

But Jeet Kune Do would not have been possible without this international exchange of profound martial arts knowledge. In the end, the system combines Muay Thai striking and southeast Asian arts known generally as silat, Filipino boxing styles (like panantukan) and weapons systems (like kali, arnis, and eskrima), Wing Chun hand techniques from the world of Kung Fu like trapping and energy training, and more. The art is as adaptable as they come, and requires the student to make decisions about what works best for his or her body, playing to strengths and advantages while discarding what works less well for each body type and ability level.

I didn’t start training martial arts to get in the ring as a fighter or even to get fit. I certainly did get fit, and my body changed completely as a result of up to three hours a day, six days a week spent rolling around on the sweat-drenched mats of my academy. But practicing Jeet Kune Do, Muay Thai, and Brazilian Jiu Jitsu also trains my mind. I practice discipline and patience, self-acceptance and the acceptance of others, strategy and control, self-awareness and spatial awareness, dedication and commitment and the deepest kind of nourishing breathing. Training martial arts has made me a stronger person physically, but it has also made me a better human.

MQA Just Ruined My Stereo

[Please note: this piece was originally run in Copper #6, when distribution of MQA and MQA-encoded files was still very limited. Seth wrote in anticipation of things to come, and was looking forward to not just the effect of the process, but its disruptive effect upon the field, as well. —Ed.]

Not just broken, but broken into a thousand worthless pieces.

Sure, it still works, but reading these articles about MQA makes it sound worse. Far worse.

MQA, we’re promised, will remove digital artifacts, open up the soundstage and clear away the veils. It isn’t just a dramatic step forward for digital—it leaves analog in the dust.

Of course, the very existence of MQA means that the music I’m listening to right now is rife with digital artifacts, closed in and veiled. This music, the music that was so majestic and real just two days ago, has been muddied and rusted by a few articles in a high end magazine.

If you ever needed proof that this is all in our heads, there it is.

MQA sounds like a sort of artless April Fool joke. Not only is the music better, better in every single way, but it streams, quickly and easily, without regard for bandwidth. I’m never going to need to buy another piece of music, in fact, I won’t be able to buy high fidelity music, because all the good stuff will only be streamed. All I can listen to for the cost of one vinyl record a month.

Here we are then, on the precipice of wonder, in the magical moment where hope has to be so much better than reality ever could be. So why does it feel so unsettling?

Isn’t this what we’ve been working for generations? Perfect sound, and not only that, but every record ever recorded! They drive a truck to your house…

The challenge that I’ve got, and that you may have as well, is that every change comes at a cost, even the change to perfection. Change means giving up the things we liked in order to have things we might love.

I’ve been buying music for forty years, and I’m not going to be able to have that pleasure again, not if I also want perfect music.

And the act of looking through the music I already own, being prompted by proximity and juxtaposition–that goes away once I’m streaming all the time. No need to spend any time at all imagining what a better cartridge might contribute, or whether or not that record, that physical totem, is clean enough, static released enough, flat enough…

But most of all, as far as I can tell, this is the end of the road.

It can’t get better after this.

The original master, from the vault, straight to me.

Sure, there will be revisions to the software, incremental improvements. But they won’t be giant leaps, and they’re likely to not be announced. They certainly won’t require a wholesale shift in our habits.

And you know what, now that I think about it?

I can’t wait.

(Originally published in Copper #6)

Immersion

You’ve probably already figured this out, but I am innately distrustful of fads, buzzwords, and whatevers du jour. I never read a book while it’s on the NYT bestsellers list. If it still holds up after a couple years, maybe I’ll read it then. But not while it’s on that damn list.

One of the buzzwords I distrust is “immersive”. Yes, I’ve used it myself, describing how better audio gear makes for “a more immersive listening experience”—and it’s true, it does indeed. But at the same time: what the hell?

Going back a ways to my Memphis years, the only time I heard the term “immersive” was in reference to baptism—the dunkers versus the sprinklers. If you don’t know what that means, that’s just fine; in fact, count yourself as lucky. But just imagine a swimming pool: when you plop yourself into it, you are immersed in the water—right? Submerged, enclosed, enveloped, covered up. Immersed.

Usage of “immersive” and “immersion” these days is mostly figurative, meaning to become deeply involved in something: that whole “immersive experience” thing. I guess that’s in contrast to…the lack of engagement that marks everyday life?

See, that’s the part I find disturbing. It says to me that our daily lives are spent in superficial non-involvement with everyone and everything we encounter. Given that the people I meet can barely tear themselves away from their phone screens to acknowledge my presence, much less actually engage in a conversation with me, I would agree that such seems to be the case. That makes me sad, and it pisses me off.

We skate along through life like the puck in an air hockey game, gliding above everything, assiduously avoiding any contact, either physical or emotional. Anything beyond a carefully-timed handshake is battery, and any too-personal question or comment is assault. God help you if you look someone in the eye for more than a couple seconds.

Are we that fragile? Honestly? I don’t think so.

Another buzzword that has paralleled the rise of “immersion” is “passion”. Every business book, blog, website, whatever, trots out that hoary term to describe any level of interest beyond cursory curiosity. We read of entrepreneurs who proclaim their passion for, oh, reusable diapers. Or organically-grown kale. Or car polish. Pretty much any item you can think of, SOMEbody out there has a passion for it.

My objection with that multiplicity of passions is that, just like immersive everything, it diminishes the meaning of the word. It creates an all-or-nothing world, in which emotions consist only of flattened affect or reality-show rage, with no middle ground. It also encourages trite usage of the same words over and over, rather than encouraging development of a broader vocabulary. It’s rather like the way that “awesome” has become the all-purpose adjective for any positive experience, event, or item.

Sorry, but not everything is AWESOME. No matter what The Lego Movie says.

As I’ve mentioned before, my daughter Emily is far wiser than I. I suspect this is one of those times when she’d say, “Dad, I think this is more a YOU issue than a THEM issue.” And she would likely be correct.

I tend to obsess over meaning, and lack thereof. I like the fine shades and gradations of meaning that can be created by use of just the right word, and am dismayed by the posterized, polarizing language that dominates common speech in these times. For one who can be horribly crass and in-your-face, I do demand a certain subtlety in communication.

But the problem is mine, really, and not the problem of those immersive, passionate types who dominate our pages and airwaves with their pep-squad prose and relentless fervor.

When I was a kid, I didn’t understand how someone could be, say, a lepidopterist who devoted his life to the study of one particular family of butterflies. In the blue-collar meatpacking town in which I was born, such a person would’ve been viewed with amusement and a little concern, and likely labeled a “weirdo”…the same way that we kids viewed the male neighbor who dressed in full witch’s attire at Halloween. But: while collecting butterflies and pinning them to a board for a school project, I began to understand the appeal of the subject, the allure of order and the understanding of a big picture beyond oneself. Later on, it gave me a little more understanding of one of my high school biology teachers, a PhD who specialized in lepidoptera.

Did we still think he was weird? Yes, but that was due more to his personality than his specialty. After all, most of the kids in the class had parents who were college teachers or researchers; by then, we were well-acquainted with adults with obsessions.

Later, as a college student studying mechanical engineering, I was baffled by the EE students, whose interests seemed so much more ephemeral and theoretical than the pumps and gear-drives and camshafts I studied. I came to realize that for many EE students, as with mathematicians, that was much of the appeal of the subject. It could be carried with them at all times, worked on and puzzled over…all in their heads.

Convenient. And indicative of a real passion, not the hysterically-hyped infomercial variety, and of a mind truly immersed in its subject.

Now—something like that, I have no problem with.

The Beauty of Song Part 2

[In the last issue of Copper, Jason Victor Serinus introduced us to the beauty and communicative power of art song. That story paves the way for what follows below.—Ed.]

One of the great joys of many art song aficionados is comparing multiple interpretations of the same song. Conducting a YouTube search for Schubert’s great hymn to music, “An die Musik” , yields page upon page of very different versions of the song. Some are from its greatest exponents, while others are by students, amateurs, and professionals who demonstrate that they would be wise not to try to make a living from art song.

Let’s begin by visiting the song’s original German and English translation:

Du holde Kunst, in wieviel grauen Stunden,

Wo mich des Lebens wilder Kreis umstrickt,

Hast du mein Herz zu warmer Lieb’ entzunden,

Hast mich in eine beßre Welt entrückt,

In eine beßre Welt entrückt!

Oft hat ein Seufzer, deiner Harf’ entflossen,

Ein süßer, heiliger Akkord von dir,

Den Himmel beßrer Zeiten mir erschlossen, Du holde Kunst, ich danke dir dafür,

Du holde Kunst, ich danke dir!

You, noble Art, in how many grey hours,

When life’s mad tumult wraps around me,

Have you kindled my heart to warm love,

Have you transported me into a better world,

Transported into a better world!

Often has a sigh flowing out from your harp,

A sweet, divine harmony from you

Unlocked to me the heaven of better times,

You, noble Art, I thank you for it,

You, noble Art, I thank you!

Let us begin with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, the soprano who, in the decades following WWII, recorded more German art song than any of her rivals. Though Schwarzkopf owed her ubiquity as a recording artist in no small part to her marriage to Walter Legge, the record producer for EMI who also worked with Maria Callas, it is nonetheless true that her superb instrument and piercing intelligence were destined to make her the German art song soprano specialist of the 1950s and ‘60s, whose few rivals included the very different-voiced Irmgard Seefried :https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S3r3FzAGqeE and Lisa della Casa https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=guR7wnALheg.

Schwarzkopf had already amassed a sizable post-war discography when, in 1952, Legge brought her to EMI. Here is her famous rendition of “An die Musik” recorded with Edwin Fischer in 1952, as she was approaching her 37th birthday:

We next jump ahead eight years to ponder the differences between Schwarzkopf’s early rendition of “An die Musik,” and her 1961 video of the song with Gerald Moore: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bm_AKMV0ME0 . Not only does Schwarzkopf sound fresher on the earlier version, but she also allows herself to sing softer, with great intimacy. Head tones that in 1953 float naturally, sound more effortful eight years later, and are placed in a more self-conscious manner. The voice is also more covered in the midrange.

But there’s far more to a successful performance of “An die Musik” than technique, sheer beauty of voice, and thrilling head tones, all of which Schwarzkopf had in spades. The basic question that must be asked, with this or any rendition of a song, is if it convinces. Is the singer true to meaning of music and words? Have they internalized them to the extent that the song seems to be flowing naturally, from the center of their being? Or are they perhaps faking it, and doing all they can to sound as though they believe in and feel deeply what they are singing?

Does Schwarzkopf sound as if she is truly singing a hymn to music? Does her professed devotion, as reflected in her body language and gaze in 1961, seem real? Or does she instead seem as though she is constantly thinking about how best to sound devout and grateful?

For contrast, I turn to the lower-pitched, noticeably slower 1949 recording of “An die Musik” by English contralto Kathleen Ferrier and Phyllis Spurr:

Here, beyond the sheer beauty of Ferrier’s remarkable voice, we can sense a depth of feeling – a virtually egoless piety – that seems far removed from Schwarzkopf’s studied approach.

For more analysis of Schwarzkopf’s singing, and comments on her newly remastered early commercial recordings from 1946-1952, please see my piece on Stereophile.

Here are several more clips of “An die Musik,” performed by some of the greatest singers of the last 100 years:

—English Mezzo-soprano Dame Janet Baker with Murray Perahia https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pt19nrxdVb4, an interpretation especially notable for the hushed sincerity with which the duo begins the second verse.

—A second version https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w1DB5xB0RyM by Janet Baker, recorded with Geoffrey Parsons. How can one not believe this woman when she sings?

—Dutch soprano Elly Ameling with Jörg Demus in 1970 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3TDEyW9JLuc, a performance beautiful in its simplicity, and perfect, save for the breath in the middle of the first phrase of the second verse.

—As she aged, Ameling became a deeper but no less lovable artist. Here, in her retirement, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tD8_UKfdnsM she talks about “An die Musik,” and then offers up her finest commercial recording of the song. You can hear it in better sound here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Wfohl-zEDU&index=2&list=PLGneby1hN84M8tp0Bo2lVbERKEdicS6_i. It took going through 13 pages of “An die Musik” on YouTube to find both of these videos. As you can hear, the hunt was worth it.

—The totally idiomatic Spanish soprano Victoria de los Angeles with Gerald Moore https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e-E7IicGOfQ, who, albeit a bit self-consciously at first, manages to transcend artifice and charm the pants off this song.

—English tenor Ian Bostridge and pianist Julius Drake, with Bostridge fussing even more than Schwarzkopf with this simple song.

—French baritone Gérard Souzay was a bit past his best and trying a bit too hard when he recorded this version https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mvNVPzudBis with Dalton Baldwin in 1967. Nonetheless, there is something very special about the end of the second verse.|

—The variety of vocal coloration is extraordinary in this recording https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4-qYwh4e6i4 of the great Welsh bass-baritone, Bryn Terfel, accompanied by the equally great Malcolm Martineau. Does it convince you?

—The one and only Spanish soprano, Montserrat Caballé, with Alfredo Rossi, captured live in Buenos Aires at the start of her international career. Caballé’s many indulgences, which include arbitrary pianissimos and stretched notes, demonstrate why she is not famed for her lieder singing.

—The great lyric tenor Fritz Wunderlich https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D-VqK088TF4, who died in his prime, may not invest the words to “An die Musik” with a plethora of individual touches, but his singing is so beautiful that the performance succeeds. The slowing in the second verse is very special.

—Ditto for this lovely performance https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H9TlAOKCmaQ by soprano Felicity Lott.

—For sheer gravity of utterance, you can’t do much better than bass-baritone Hans Hotter https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFsaO7lZ6JU.

—For contrast, here is the beloved soprano, Elisabeth Schumann with Gerald Moore in 1936:

Schumann’s voice had already peaked, but her sincerity and intensity, and the beauty that remains of her unique top, transcend all technical limitations. No one on record has ever sung like this.

As much as I wish to stick with “An die Musik,” I cannot resist linking to this rare film of a younger Schumann singing parts of Schubert’s “Ave Maria”:

The sound may be poor, and the visual conceit decidedly old-fashioned, but the singing is heaven itself. When Schumann’s voice rises to her incomparably pure, glowing top, she radiates golden light. Her miraculous commercial recording of “Ave Maria,” recorded in 1934, is a treasure. The way Schumann rounded off phrases was unique:

—Returning to “An die Musik,” here is the incomparable German soprano Lotte Lehmann https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dxsETaJxMJw, with orchestra. Lehmann may sing slower than she comfortably can without taking breaths in the middle of phrases, but she nonetheless expresses an uncommon depth of feeling. The voice is like no other in its combination of gravitas with beauty.

—In 1941, Lehmann was 53 when she appeared on the radio https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=81-g46Z_3Fk with Paul Ulanowsky to introduce and sing a host of great songs. Extra breaths again intrude in this version of “An die Musik,” but her heartfelt sincerity is beyond question.

—The best Lehmann version of “An die Musik” was recorded in 1947, when she was 59 years old:

It tears my heart apart to hear how much love she pours into this song. While the age in the voice is apparent, its greater depth actually makes for a more convincing interpretation.

Four years later, Lehmann stunned a Town Hall audience by announcing her retirement in the middle of what turned out to be her last New York recital. As an encore, she attempted to sing “An die Musik.” Overcome with emotion, she walked off the stage in the middle of the second verse rather than breaking into tears, and left it to her accompanist, Paul Ulanowsky, to pick up the pieces.

—In this single verse, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0yyIqN-E96Q , French baritone José van Dam gives us a sense of why he is so highly prized.

In the baritone range, the one man who dominated the field of German art song (lieder) from 1951 through the mid 1980s was Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. An extraordinarily versatile singer, who also excelled in the vocal music of Bach and Mahler and the operas of Mozart and Strauss – he even sang Verdi and Wagner – Fischer-Dieskau was virtually ubiquitous in recording studios during the prime of his career. In some years, a month rarely went by without another Fischer-Dieskau recording.

Here is Fischer-Dieskau singing “An die Musik” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RxsFgJF6XS4. As beautiful as his voice may be when he softens, it is hard not to notice how much he varies volume and tone, and pays special attention to the consonants and vowels of certain words.

Following other Fischer-Dieskau links on YouTube somehow took me to this:

…and to this:

A PBS remembrance of the man, recorded just days after his death, it is remarkable in that it honors the singer by presenting, not just a snippet of his singing, but rather an entire extraordinary performance intact. Equally important, it includes an interview with Washington Post chief music critic Anne Midgette at her perceptive best.

Fischer-Dieskau’s prime was unusually long. The tribute’s clip, a song from Schubert’s great song cycle, Winterreise (A Winter’s Journey), was recorded in 1979, when he was 54. Just one year earlier, he retired from opera. His prime probably would have extended far longer had he not smoked so much. Nonetheless, if this citation his true, he could still sing magnificently when he was 62: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=td5rg_p0z2c .

After you get a sense of how well Fischer-Dieskau could sing, this snippet from his final interview, conducted shortly before his death at age 86, provides great insight into how he viewed art song in the context of opera: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yyBBb0izYmM .

There is so much more one can say about art song. Truly, I’m just getting going. Let me end with several very different performances of Mahler’s great song cycle, Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer) by Fischer-Dieskau. This is the music that first introduced him to an international audience, and helped make him a household name.

The first https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tKpjJCvWxRg , from 1952 with Wilhelm Furtwängler, was recorded commercially one year after the men performed the cycle together at Salzburg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2sMLTC1lGEk . This live performance first surfaced decades after the commercial recording had made its mark.

In 1960, Fischer-Dieskau joined conductor Paul Kletzki, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ur-3LrpgB0Y for a filmed performance of the cycle. Note how his interpretation had changed in the intervening years. In general, the older he got, the more he tried to do with a given piece of music.

For contrast, here is the famous recording https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CMZmuV5vrlU of Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen by Janet Baker with Sir John Barbirolli. Finally comes the latest recorded version by a great mezzo, from Alice Coote with Vladimir Jurowski. My review of that recording for stereophile.com, contains a very detailed discussion of performances of three Mahler song collections, and I urge you to read it.

While Coote and Jurowski’s Pentatone SACD is not on YouTube, we have in its place clips of them performing Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen at the BBC Proms in 2012 (complete with English translation). Broken into four parts, you can find the performance here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XKoYyABuTio , here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yrGMh3LQWeY, here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XrGw1oxDWqM, and here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9qBUiqWdixM.

We are so fortunate to have access to so many live performances by great artists, and to live in an age where many recordings are instantly accessible. If any of the voices or performances cited in this overview have touched you, I urge you to obtain out high-quality recordings of their artistry. The better the recording and playback chain, the more nuance you will hear.

Justice