Simply submit your suggestions for the column name to letters@psaudio.com. The contest will run from now through October 31. Then we’ll choose the lucky winner!

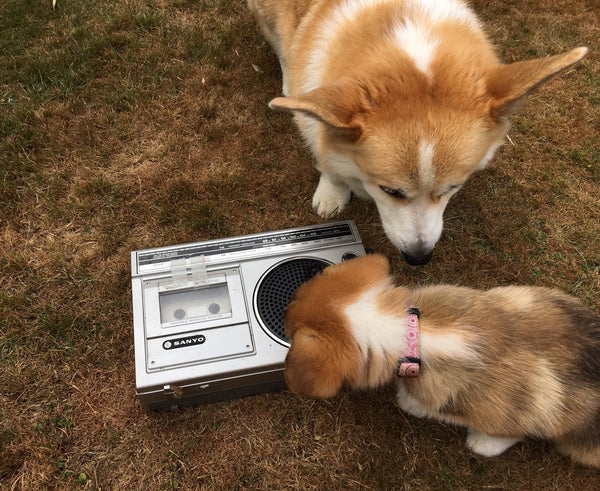

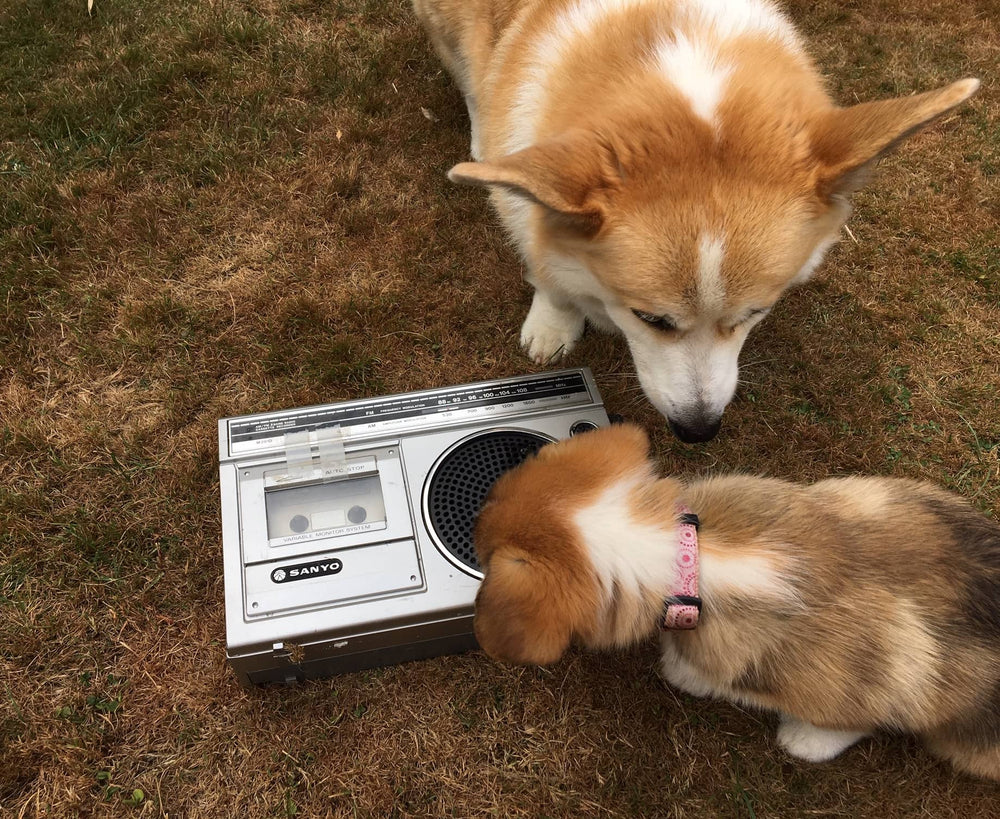

In other news: we welcome a new staff member, writer Steven Bryan Bieler. Steven is a novelist living in Portland, Oregon, with his wife, his dogs, and his CD collection. He blogs about music at rundmsteve.com.

Bob Stuart, inventor of Meridian Lossless Packing digital audio technology and MQA (Master Quality Authenticated) digital audio encoding has been awarded the Prince Philip Medal. The medal is given biennially by the Royal Academy of Engineering to an engineer who has made an exceptional contribution to engineering as a whole through practice, management or education. Congratulations Bob!

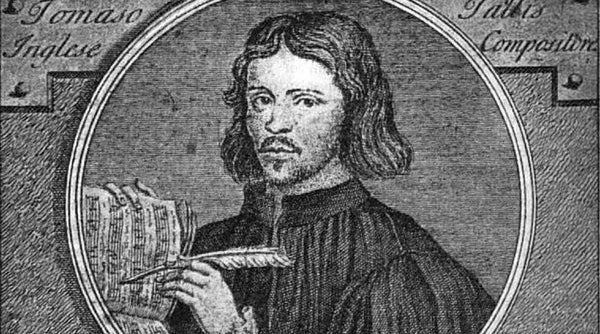

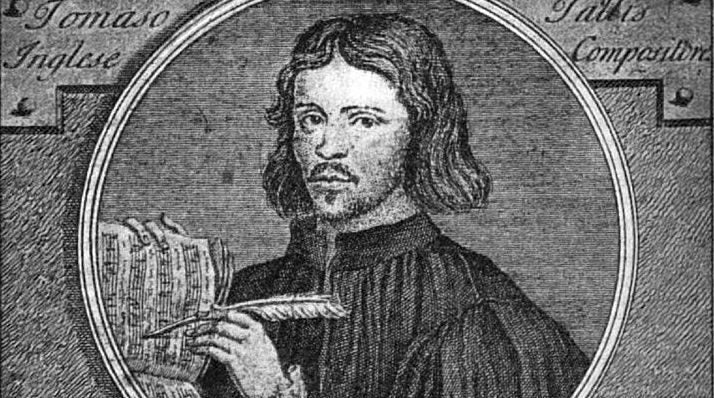

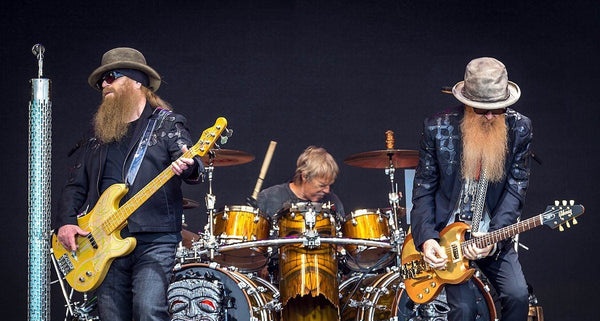

In this issue: Don Kaplan takes a fresh approach on how to listen. Roy Hall looks back on the Munich HIGH END show. J.I. Agnew concludes his interview with acoustic design consultant Philip Newell. Jay Jay French drinks in British blues singers. Anne E. Johnson considers the music of Thomas Tallis and ZZ Top. Alón Sagee tells a story of two hands clapping. Don Lindich interviews Bill Voss of Technics, and John Seetoo wraps up his series with Quilter Amps/QSC Audio founder Pat Quilter.

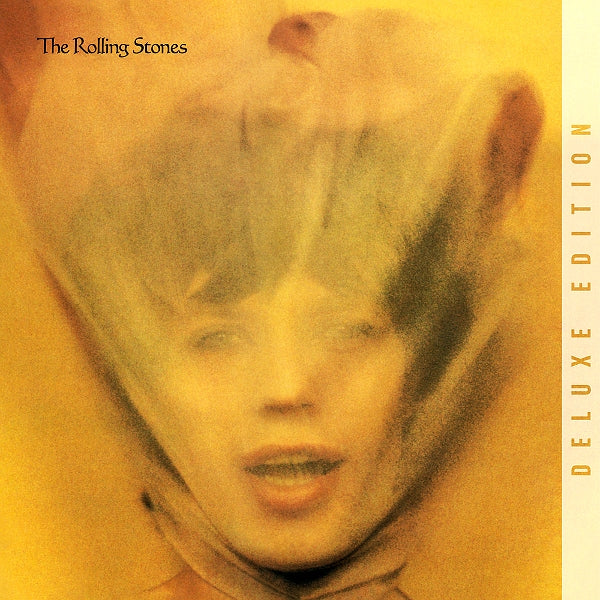

Tom Gibbs is thrilled to hear a good-sounding Stones reissue, among other new releases. New contributor Steven Bryan Bieler hears voices. WL Woodward is home for the pandemic. Robert Heiblim concludes his series on bringing products to market. Ray Chelstowski has an explosive look at K-tel Records. Ken Sander offers a Stories story. I find that audio systems are consistently inconsistent. Reader Adrian Wu takes us on an audio journey encompassing continents, and decades of gear. We round out the issue by staying in our room, experiencing changing weather and going to Nepal.

Simply submit your suggestions for the column name to letters@psaudio.com. The contest will run from now through October 31. Then we’ll choose the lucky winner!

In other news: we welcome a new staff member, writer Steven Bryan Bieler. Steven is a novelist living in Portland, Oregon, with his wife, his dogs, and his CD collection. He blogs about music at rundmsteve.com.

Bob Stuart, inventor of Meridian Lossless Packing digital audio technology and MQA (Master Quality Authenticated) digital audio encoding has been awarded the Prince Philip Medal. The medal is given biennially by the Royal Academy of Engineering to an engineer who has made an exceptional contribution to engineering as a whole through practice, management or education. Congratulations Bob!

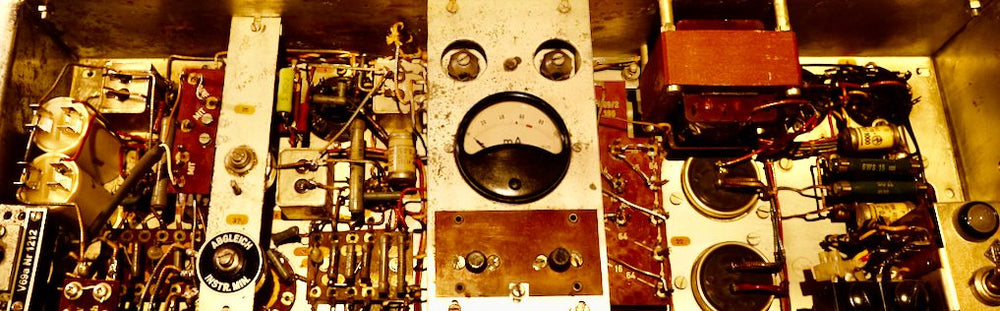

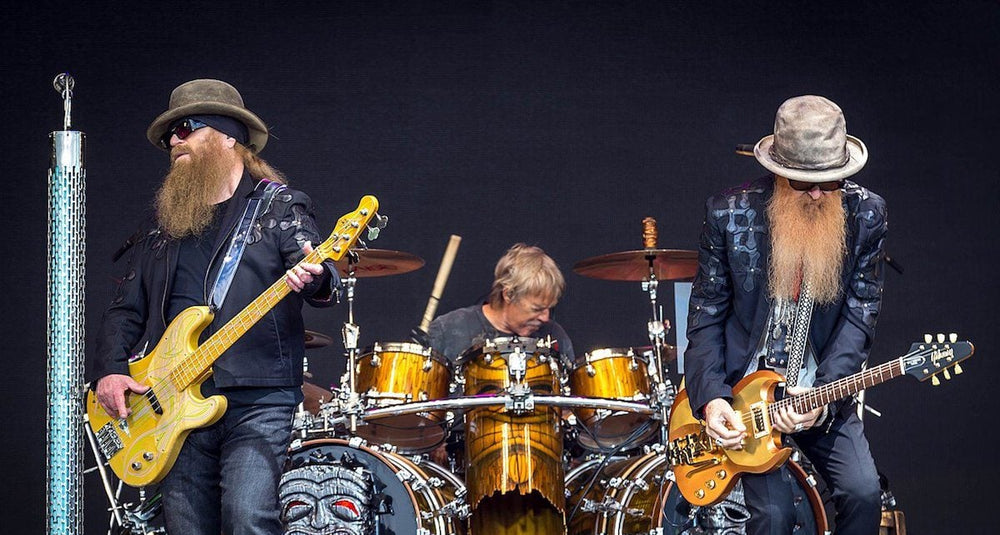

In this issue: Don Kaplan takes a fresh approach on how to listen. Roy Hall looks back on the Munich HIGH END show. J.I. Agnew concludes his interview with acoustic design consultant Philip Newell. Jay Jay French drinks in British blues singers. Anne E. Johnson considers the music of Thomas Tallis and ZZ Top. Alón Sagee tells a story of two hands clapping. Don Lindich interviews Bill Voss of Technics, and John Seetoo wraps up his series with Quilter Amps/QSC Audio founder Pat Quilter.

Tom Gibbs is thrilled to hear a good-sounding Stones reissue, among other new releases. New contributor Steven Bryan Bieler hears voices. WL Woodward is home for the pandemic. Robert Heiblim concludes his series on bringing products to market. Ray Chelstowski has an explosive look at K-tel Records. Ken Sander offers a Stories story. I find that audio systems are consistently inconsistent. Reader Adrian Wu takes us on an audio journey encompassing continents, and decades of gear. We round out the issue by staying in our room, experiencing changing weather and going to Nepal.

Loading...

Issue 120

Name That Column Contest!

Simply submit your suggestions for the column name to letters@psaudio.com. The contest will run from now through October 31. Then we’ll choose the lucky winner!

In other news: we welcome a new staff member, writer Steven Bryan Bieler. Steven is a novelist living in Portland, Oregon, with his wife, his dogs, and his CD collection. He blogs about music at rundmsteve.com.

Bob Stuart, inventor of Meridian Lossless Packing digital audio technology and MQA (Master Quality Authenticated) digital audio encoding has been awarded the Prince Philip Medal. The medal is given biennially by the Royal Academy of Engineering to an engineer who has made an exceptional contribution to engineering as a whole through practice, management or education. Congratulations Bob!

In this issue: Don Kaplan takes a fresh approach on how to listen. Roy Hall looks back on the Munich HIGH END show. J.I. Agnew concludes his interview with acoustic design consultant Philip Newell. Jay Jay French drinks in British blues singers. Anne E. Johnson considers the music of Thomas Tallis and ZZ Top. Alón Sagee tells a story of two hands clapping. Don Lindich interviews Bill Voss of Technics, and John Seetoo wraps up his series with Quilter Amps/QSC Audio founder Pat Quilter.

Tom Gibbs is thrilled to hear a good-sounding Stones reissue, among other new releases. New contributor Steven Bryan Bieler hears voices. WL Woodward is home for the pandemic. Robert Heiblim concludes his series on bringing products to market. Ray Chelstowski has an explosive look at K-tel Records. Ken Sander offers a Stories story. I find that audio systems are consistently inconsistent. Reader Adrian Wu takes us on an audio journey encompassing continents, and decades of gear. We round out the issue by staying in our room, experiencing changing weather and going to Nepal.

Simply submit your suggestions for the column name to letters@psaudio.com. The contest will run from now through October 31. Then we’ll choose the lucky winner!

In other news: we welcome a new staff member, writer Steven Bryan Bieler. Steven is a novelist living in Portland, Oregon, with his wife, his dogs, and his CD collection. He blogs about music at rundmsteve.com.

Bob Stuart, inventor of Meridian Lossless Packing digital audio technology and MQA (Master Quality Authenticated) digital audio encoding has been awarded the Prince Philip Medal. The medal is given biennially by the Royal Academy of Engineering to an engineer who has made an exceptional contribution to engineering as a whole through practice, management or education. Congratulations Bob!

In this issue: Don Kaplan takes a fresh approach on how to listen. Roy Hall looks back on the Munich HIGH END show. J.I. Agnew concludes his interview with acoustic design consultant Philip Newell. Jay Jay French drinks in British blues singers. Anne E. Johnson considers the music of Thomas Tallis and ZZ Top. Alón Sagee tells a story of two hands clapping. Don Lindich interviews Bill Voss of Technics, and John Seetoo wraps up his series with Quilter Amps/QSC Audio founder Pat Quilter.

Tom Gibbs is thrilled to hear a good-sounding Stones reissue, among other new releases. New contributor Steven Bryan Bieler hears voices. WL Woodward is home for the pandemic. Robert Heiblim concludes his series on bringing products to market. Ray Chelstowski has an explosive look at K-tel Records. Ken Sander offers a Stories story. I find that audio systems are consistently inconsistent. Reader Adrian Wu takes us on an audio journey encompassing continents, and decades of gear. We round out the issue by staying in our room, experiencing changing weather and going to Nepal.

Quilter Labs' and QSC Audio's Pat Quilter, Part Three

Founded in 1968 as Quilter Sound Company, QSC Audio has grown to become one of the most recognized global names in sound reinforcement. In Part One (Issue 118) and Part Two (Issue 119) we interviewed Pat Quilter on a variety of topics including the history of recorded sound, non-amplified vs. amplified live concerts, advancements in amplification and loudspeakers and more. The interview concludes here.

John Seetoo: Do you have a personal preference for recorded references that you like to use in evaluating loudspeakers and equipment?

Pat Quilter: I wouldn’t remember the names, but we’ve played many of the same songs for speaker testing — a repertoire of various music styles [including] jazz, pop, even stuff bordering on heavy metal. [There’s nothing] magic about the musical pieces, per se, except that they cover a good frequency range and we’re familiar with them, so we can make informed judgments like “I heard the bass better on that other speaker” and so forth.

JS: After retiring from day-to-day duties at QSC, you came back full circle to make guitar amps by forming Quilter Labs. Was there a sense of unfinished business that prompted that move, having dropped that product line early in QSC history?

PQ: Well yes. I did feel a sense of unfinished business, and when spring would roll around and the sap would rise, I would think about my old work – incorporating the time tested attributes of classic tube technology without the drawbacks. For QSC’s 40th anniversary in 2008, I dashed off a 50-watt lightweight combo with all the key elements in the current generation of Quilter products: a warm-sounding power amp, a thoroughly well-designed overdrive section, a surprising amount of nuance in the equalization curves, and so forth. It played quite well and gave me confidence in the approach.

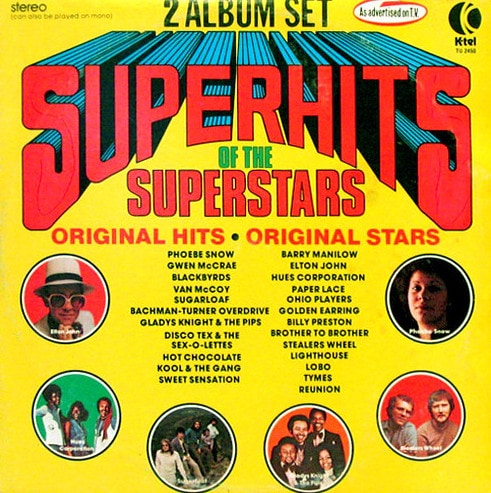

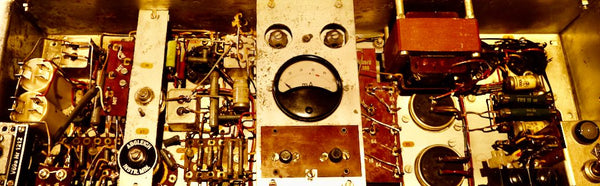

JS: You also had a hand in designing the Pignose 30/60 combo amp in the 1980s. I had one, and it was a great-sounding amp. PQ: (laughs) That’s a whole story in itself [and included in the link to the complete interview – Ed.] The 30/60 had all of the key elements that we’re using today in our amps, although somewhat unrefined. When I decided to get back into the guitar and bass amp business during my retirement, it was a combination of wanting to show the world what I could do, as well as to try to give back to the community of musicians that started it all for QSC. So I observed that guitar amp technology not only has stagnated, in that premium amps are still based on vacuum tubes, but actually has gone backwards to some degree, because the tube quality is not what it used to be back in the 1960s, when RCA used to make them by the millions to put in their color TVs. I enjoy playing music recreationally, and when I was ready to retire I thought to myself, “well, all right. What kind of amp should I get for my lap steel?” I didn’t want some big, heavy thing. No one was making a nice, warm sounding, lightweight guitar amp with enough headroom to take out and play in front of people but handy enough to have around the house. So, much to my surprise, I realized that’s what I’d be doing in my second career. And here we are today. I think that the one thing I bring to the game aside from a bunch of particular tricks is the use of Class D for guitar amps. It’s been a part of bass amplification for quite a few years, but it was a resource that hadn’t really been explored much for guitar amps until we got into it a few years ago. JS: Why do you think tube amps still carry such a mystique among guitar players? PQ: The electric guitar can now be put in the class of a “traditional” instrument, like the piano or the saxophone. The electric guitar hasn’t really changed in the almost 80 years since it was introduced. People still buy Telecasters, Stratocasters and Les Pauls, or various imitations thereof, that are all designs from the 1950s. The electric guitar grew up with vacuum tube amplification. And through a happy accident, it turned out that magnetic pickups, with their rounded tone, when played through somewhat primitive, low-fidelity, underpowered tube amps, do some wonderful things together when pushed. At first, low-power amps were all you could get, but the instinctive process of pushing an amp into overdrive opens up a second register for the guitar, one that maps the inherent “twang” into a more sustained and harmonically rich sound. When solid state [amplifiers] were first developed, the engineers assumed that players would like the cleaner headroom, but they didn’t sound the same, and they didn’t feel the same. But as I mentioned before, tubes are not as good as they used to be. So from a sheer practicality and consistency standpoint, I believe that musicians need a more reliable tool. We stand on the shoulders of giants; we’re able to look at the work that’s been done by previous generations. We study what’s good about it and where things fall short and try to emulate the good parts while correcting the bad parts. The result is a better tool to perform a familiar job for the electric guitarist and bass player. That’s kind of Quilter Labs’ mission – to make modern amps that are playable, and [will even be] collectible 50 years from now. I don’t know how many tube amps will still be operable by then. JS: Why you decided to forego digital modeling and not use digital circuitry to simulate the sounds of various tube and other amps? PQ: Let’s face it, I’m an analog guy. I understand in principle what’s going on with digital modeling, but I would have to undertake a massive catchup to be competitive in that field. And at the end of the day, the digital models are struggling to capture nuances and effects that just flow naturally from the analog circuitry they’re emulating. So why not just do it in analog? Admittedly, you don’t have the ability to get a hundred different sounds at the push of a button. But frankly, most people only need a few good sounds. If we can make really charming, good analog amplifiers, they can be the basis of a good rig that you can add to with outboard effects and digital processors to your heart’s content. JS: Among other products, Quilter makes very small “micro” amps with a lot of power and a wide range of sounds. How do you do it? PQ: Class D technology and active power supplies let us put big power in small boxes. The original, historic guitar amps from the tube era have relatively simple EQ circuits but every designer had their own theory about voicing. So [how] to get many different sounds out of a [modern] amp? One way is with a switch that selects a different circuit or [part of a circuit] or “tone stack” to give it a different personality. We use surface mount technology, which is mainstream now.[Surface mount technology allows electronic components to be directly mounted onto a printed circuit board. It enables greater miniaturization than previous “through hole” mounting techniques. – Ed.] Since it’s a lot more compact, it lets us put moderately complicated circuits into tiny, little pedal-sized boxes. Our electronic technology is more advanced than classic tube amp stuff, but I’ve got to be honest: it’s nothing like what you’d find in a digital pedal, or a cellphone. But we use the tools we have. One of my hallmarks as a designer is to seek the simplest way of getting a result, on the theory that it will save money and effort in the long run. Combine that [philosophy] with modern power amp technology, which is vastly more compact than it used to be, and yes – we can make an amp the size of a library book that cranks out 800 watts. JS: I’m going to switch gears to talk about Quilter’s Panoptigon disc player, something Copper readers might find particularly interesting. The Panoptigon plays proprietary optical discs like the type originally made for the 1970s Mattel Optigan. The Optigan was a keyboard instrument that played pre-recorded sounds stored on these discs in a similar manner as the more well-known 1970s Vako Orchestron (or the Mellotron, which played sounds stored on strips of magnetic tape). Why did you decide to offer this unusual product?

The Panoptigon.

The Panoptigon.

PQ: Robert Becker was my project manager at QSC and has become a vital part of the team at Quilter Labs. Some years ago he was looking at a hanging mobile that emitted a light display, and remembered seeing something like that online. He discovered that it was a British system developed in the 1920s to automatically tell you the time when you dialed up the phone number. It had rotating glass discs with [recorded voices for each digit] on them. That led him to a fellow named Pea Hicks, who had created a website celebrating the Mattel Optigan, [which] everyone had more or less forgotten about. Of course, we all know Mattel as a toy company, but they apparently had ambitions to get into a higher-price-point adult toy range by making home organs. Now, the home organs of the 1960s came in two classes. You had cheesy little reed organs with chord buttons, or you had elaborate electronic organs such as the Hammond or Gulbransen, which cost thousands of dollars, were as heavy as a piano, and were serious instruments that also required keyboard skills to play them. So, somebody at Mattel came up with the idea: if we recorded rhythm tracks instead of just having chord buttons, you could sound like an orchestra playing while picking out the melody on a small keyboard. And we can then sell various styles of music on discs plus E-Z Play songbooks. They’d set these Optigans up outside the organ store at the neighborhood mall and collar people. “Look! You can be a musician! Hold this button down!” – and you’d hear, “shung-a-lunga-lunga” (rhythm sound). “Now play these notes! Two fingers and you’re playing a song!” They sold these things for $600. They had a surge of popularity and planned to release an endless stream of new discs so the thing wouldn’t go stale, but – the machines just weren’t very well made. The discs, made out of clear film. began to slip; wouldn’t stay in tune and if you didn’t take care of them they’d get scratchy pretty quick. So after a couple of years, the Optigans all wound up in the closet. Forty years later, Pea Hicks becomes fascinated by this history, digs up some interesting material, and manages to contact one of the remaining engineers who had worked on the project. The engineer had kept a carton full of memorabilia about the Optigan, including never-issued master tapes! So Pea got his hands on all this stuff and started featuring [it] on his website. Robert stumbled across this and chatted Pea up on what was going on. Pea mentions, “My Optigan needs restoration. You’re in electronics, aren’t you? Could you do something with it?” So Robert winds up restoring several Optigans. It was a frustrating job. The electronics and transport were primitive and even with great effort, never really worked that well. Robert ended up saying, “I could make a better one from scratch.” Long story short, he came up with our Panoptigon. It uses a servo-controlled drive so you can set it to discrete pitches. It has the ability to start and stop from [a MIDI-linked] keyboard, you can [play the discs] backwards, [change the pitch]…and many other user-friendly features [and improvements]. After the Optigan came and went, another company, Vako, issued the Orchestron, which used the same disc format, without the rhythm tracks. The Orchestron [was designed to] to compete with the Mellotron, which used little strips of tape that gave you the actual notes, but could only play for eight seconds before the tape had to rewind. You can imagine how finicky a machine like that would be. The Orchestron was somewhat better built, [and] more capable of being hauled around on tour. But they too gradually went under. Digital synthesizers and sampling keyboards put all these guys out of business. So now we come to the present day, where the optical discs have become kind of an art form in themselves. They do have a distinctive tone quality, and the limitations of the format, with everything in two-second loops, can actually lead to artistically interesting results. You can experiment with recursion and create interesting rhythm patterns. Pea had mentioned he had all of these unissued tapes and lamented, “It’s too bad no one’s ever going to be able to record new discs.” Robert thought, “I can think of a way to do this on a computer with a .WAV file and an art program” [without using an optical recording head]. So by using modern resources, he can actually master optical discs from scratch. [As a result] Pea has been able to release some never-before-issued disc Mattel [would have issued but never did], as well as create new ones. They’re having a lot of fun with it, and…it’s of my unspoken missions for Quilter Labs to do cool things that you couldn’t justify on a business level, but that somebody ought to do. So this was one of our opportunities to bring something to market that may have a small band of aficionados who appreciate what we’ve done. It’s an interesting, creative piece of work [and] I don’t know where else you might have gotten something like that to happen. JS: I can imagine someone like Brian Eno getting one. PQ: There have been a couple of famous keyboard players who have either acquired or expressed an interest in getting one. It does things you can’t readily do on other keyboards, so it’s kind of its own thing. JS: As a musician yourself, do you share the notion that music is a language and that musicians communicating with each other and with an audience through music is the primary goal for the existence of music? PQ: I absolutely see music as a language. I think one of the most fascinating elements of music is that I can go to a foreign country where I don’t speak the language, but if I find a fellow musician, if we sit down, chances are we can make music together. I can listen to what the other person is doing, they can listen to me, and we can end up doing something together that harmonizes. And of course, the word “harmony” is fundamental to the practice of music. Heaven knows we could use all the harmony we can get in today’s world. “Harmony” has always been a part of QSC’s culture. It’s even on our official mission statement. The act of collaborating with other musicians in real time, working in a pure art form, is practically unique to music [although you see this kind of collaboration in sports]. Of course, a solo musician can be pretty impressive. But an ensemble, for me, is where it’s really at. You work with other people, hear new ideas, build on them, it triggers something…if you have experienced the joy of a good musical session, you come away feeling, “I just went someplace I’ve never really been before, and it was great!” And you live for those moments. If QSC and Quilter Labs can help deliver high-quality gear that’s [easy to] get a good sound [from], and [help people] pursue making beautiful music, I will feel that I’ve done something helpful for the world. JS: Music has evolved through innovations in technology that expand the possibilities of what kind of music can be created. In what ways would you characterize technology as a disruptive force for musical change over the past hundred years, and how would you place the contributions of QSC Audio and Quilter Labs in that timeline? PQ: Back in the 1960s when I was young and knew it all, by virtue of having a record collection that went back to the 1920s, it did seem to me that music changed dramatically about once a decade. You had your ragtime era, then the hot bandstand music of the 1920s. The driving technical impact of this era was the fact that music could be recorded at all, so that a band could make a hit record and actually make money off record sales, instead of having to perform over and over again. In the 1920s the introduction of electric recording “opened up” the sound quality of recordings, which led to the more percussive, string-bass-driven swing era of the 1930s, and enabled soft-voiced crooners to become popular entertainers. Of course, this was coupled with the advent of radio, which allowed recorded and live music to be piped into millions of homes at the same time. In the 1930s, the Big Band still remained the way to fill a dance hall with exciting sound. For most of the 1930s, the “vocal chorus” remained a one-verse interlude, but as wartime travel restrictions set in, vocalists backed by a combo took over. The big technology of the 1950s was, of course, the rise of the amplified electric guitar. A small, four-piece combo could fill a dancehall with loud, exciting music. And in the 1960s, amps became bigger and louder, overdriven amps [and distortion] became a thing, and we had this fantastic outpouring of musical creativity, just as I was just getting started in the business. The last thing that I expected was that we would still be listening to those same songs, 50, 60 years later, which is kind of unprecedented. Nobody in the 1960s was listening routinely to music recorded in 1910. I firmly expected that some new technology would let the next crop of musicians dazzle their peers with fresh material. Although the guitar is a great stage instrument that lets you jump around and sing, I didn’t really expect the advent of the modern keyboard. A good player on a keyboard can of course sound like several musicians at once and play bass lines, chords and melody lines and sing at the same time, which you can’t do playing a horn. The economics of music performance continued to drive the music towards fewer performers making a bigger sound, which kind of culminated in DJs and rap artists, stripping the song down to vocals and a rhythm section, or even just a drum track. It’s fascinating to trace the history of popular music as the systematic paring away of elements in favor of lyrics and rhythm. But at the same time, even though rap is [so popular], other forms that involve more players and melodic elements have remained in play. So we have a very fragmented music scene now that’s not as monolithic, for [lack of a better term], than what we had in the 1960s and 1970s. People then were always waiting for the next big thing. We would all drop everything to check out the new Beatles album. That really doesn’t happen anymore. At the same time, it does mean there are more [musical] outlets than ever. As home video became affordable, I thought that video technology would be one of those major enabling factors that takes music in a new direction, much like the advent of the PA system. I don’t see much evidence that this has happened. It seems like video is just another kind of fancy lighting or effect. It’s an embellishment of [the music], but it’s not an element in its own right. Maybe there are creative people out there blending sound and motion in new ways that I don’t know about, but I would have thought there would be a form of music that involves creative motion as much as creative sound. JS: Where would you place the contributions of QSC Audio and Quilter Labs within that timeline? PQ: In terms of live sound and music, you could fairly categorize both companies as essentially second-to-market companies. QSC did not invent the powered speaker or the power amplifier, or any of the other things that we do. We have seen trends developing and have gotten in on them, tried to learn from the efforts that went before, and tried to do a better job [with products that are] hopefully more streamlined and easier to operate. We try to smooth off the rough edges and raise the state of the art. By the same token, although I still have some hopes of doing highly original things at Quilter Labs, most of our projects have been efforts to do a known job better with the goal of establishing a revenue base to underwrite the development of more out-of-the-box types of things. This interview is taking place in the middle of a worldwide health crisis, but hopefully we’ll soon be able to have people return to enjoying live music in groups again. That will be nice. But now it’s interesting to see what people can do online. JS: Pat Quilter, this has been wonderful and I thank you for your time. I know you’re a pretty busy guy. PQ: It’s been a fun talk. Thank you John. Editor’s Note: There’s a lot more of this interview that we didn’t have the space for, and if you’d like to read the complete text of Pat and John’s conversation, please click on the following link: Pat Quilter: Complete Interview

QSC GXD 8 power amplifier.

QSC GXD 8 power amplifier. QSC WL3082 sound reinforcement loudspeaker.

QSC WL3082 sound reinforcement loudspeaker.

Majestic Mountains

Annapurna Massif, Nepal, looking at Annapurna I peak, 8,091 meters (26,545 feet) high. The photo was taken near the ancient Tibetan village of Phu near the Nepal-Tibet border. That is a Mani stone wall; each stone has a hand-carved Tibetan prayer. The particular village is now a ghost town used only by traveling yak herders and trekkers. The town was wiped out around 1918 by what we now believe was the Spanish flu pandemic. The few survivors thought the village was cursed, so no one ever moved back.

A Conversation with Technics’ Bill Voss

Technics is a brand that needs little introduction to most Copper readers. Technics was once a household name in consumer electronics but eventually faded to the point where the marque was discontinued. In 2015, Technics was brought back with the introduction of new high-end audio systems. Following is an interview with Bill Voss, Business Development Manager/US of Technics.

Don Lindich: Technics has seen a lot of changes since the brand was launched by Matsushita/Panasonic in 1965 as a Nakamichi competitor. As time went on the Technics name was used on mass-market equipment and rack systems, and later became something of a DJ brand as DJs adopted the SL-1200 turntable as the industry standard. After a period of dormancy from 2010 to 2015, the brand relaunched with an uncompromising high-end purpose. Do you see this as a return to the roots of the brand, or an even higher level of aspiration entirely?

Bill Voss: I see it as both. Our roots are [in] the many innovations Technics engineers have introduced over the years to a wide audience, and remain the fundamental building blocks of the new line and future developments. [The new] Coreless Direct Drive [turntable motor], for instance, was an improvement on the direct drive motor Technics invented in 1970. The concept for improvement was based on analog [design] principles with the addition of modern digital technology and materials among other things, to [ensure] the most accurate platter rotation.

DL: Reflecting on the previous question, sometime after the audiophile versions of the new SL-1200 turntable were released (the SL-1200GAE/SL-1200G/SL-1210GAE/SL-1200GR/SL-1210GR), Technics introduced a turntable for DJs, the SL-1200MK7. Was this part of the plan all along? How will you keep the Technics image and brand value high with audiophiles while also serving the DJ market?

SL-1000R turntable.

SL-1000R turntable.BV: Turntables in general were not part of the plan. At least, not the plan I was given at CES in 2015, where Technics introduced two complete cutting-edge high-res digital audio systems to address the growing desire for ease of streaming digital music from computers, NAS servers, other devices and app sources. I believed in it and is certainly the reality now. But we didn’t ignore vinyl playback as both our Premium and Reference systems could accommodate the highest-quality phono stages if users chose to enjoy [vinyl]. At that time, the SU-C700 Premium Class integrated amp had a dedicated phono section and the SU-R1 Reference Class when used as a preamp had the option of an outboard phono stage for wider flexibility. Our new Reference Class SU-R1000 integrated amplifier, which was just announced, will again offer cutting edge technology with a very unique Intelligent Phono EQ to cancel crosstalk, optimize gain and phase (similar to the LAPC Load Adaptive Phase Calibration amplifier/loudspeaker interface technology) and improve accuracy of the EQ curve.

However, most everyone visiting us at CES 2015, while excited to see Technics back in the business, couldn’t help but ask, “when are you bringing back the turntables?” We told visitors that there was no turntable in the plan, we had done that already, vinyl was on the downswing, and how could we ever [equal] the monumental success that Technics turntables had in the 1970s and 1980s? So, while not in the plan then, [turntables] certainly must have been on our engineers’ minds because just one year later in 2016, we arrived back in the same suite at CES with the new $4,000 SL-1200GAE/G.

The turntable world was suddenly in an uproar with the announcement. But while the new Coreless Direct Drive [motor design] drew mass appeal from the audiophile community (and was considered a bargain at the price), it broke DJs hearts who were expecting a lower price. Of course, Technics rebounded the following year with another new 1200 model, the SL-1200GR, which set out to bring most of the SL-1200GAE/G experience at half the price. And it was very successful but still not quite the sweet spot the working pro DJs were looking for. So, at CES 2019 we introduced the SL-1200MK7 which now seems to be the right model to return us to favor [with DJs].

So, it seems we never really turned our back on vinyl. It just took us some time to ramp back up. I’m so glad we did. I mean, these days, everyone is enjoying vinyl, getting back into or trying it for the very first time.

DL: Are you finding that any consumers or audiophiles on a budget are buying the SL-1200MK7 as a hi-fi turntable? The SL-1200GR is a great audiophile turntable, but $1,699 is a far cry from $999.

BV: It’s hard to know exactly who is purchasing it but sales on the SL-1200MK7 are brisk, proving the MK7 with its Coreless Direct Drive motor, while certainly a top choice as a DJ “tool of the trade,” is also earning its place as an incredible audiophile bargain. With that starting price point, it lends itself to endless tweaking [in] trying various aftermarket AC power cords and interconnect cables, isolation feet and platter mats and it accommodates a wide range of cartridge and headshell combinations for various [types of] LP playback. Not so much of a secret anymore.

DL: Traditionally audiophiles have had a strong preference for belt drive turntables and shied away from direct drive turntables. Your current direct drive turntable line seems to have largely changed that, receiving highly positive reviews and widespread acceptance in the audiophile community. In a hobby that has passionate followers with prejudices and opinions that can be hard to change, how did you do it?

BV: The proof is in the pudding as they say. The engineers certainly did their homework. Turntables are analog components, but the new Technics models incorporate multiple digital control systems. Some models can even accept a firmware update! There are many fine details in the design of the new motor and control system. We try to explain them all [in our product descriptions] but [you’d need to be trained in] engineering [to have a full] understanding. The extra steps taken to assure perfect rotational accuracy from table to table in the manufacturing process, so that each one is as perfect as the next, is an example of Japanese engineering at its best, beyond the call.

DL: What product categories do you compete in, and how many different products does Technics now offer in North America?

BV: Over the years Technics has held the appeal of professional DJs as well as audiophiles. And we continue the 2-channel only tradition (no multi-channel or home theater gear yet) with our new line of turntables, loudspeakers, network-connected CD/SACD players and true-wireless earphones. We also offer digital amplifiers with proprietary functions like LAPC Load Adaptive Phase Calibration, which enables flattening of the frequency characteristics of amplitude and phase, which had previously not been achieved by amplifiers, as well as delivering a sound with richer spatial expression.

We recently added some specialty products like the Ottava Series of wireless speaker systems that are complete all-in-one, high-res audio solutions with networking, internet radio, access to streaming services like Spotify, TIDAL, Deezer and Chromecast built-in, and compatibility with Google Assistant. All [of this is] controllable from your handheld device via the Technics Audio Center app.

SL-1200G turntable.

SL-1200G turntable.DL: Who do you see as your target customers and target markets?

BV: We continue to address the professional DJ’s need for a reliable tool of the trade with the MK7 turntables in particular, and to provide cutting-edge luxury products appealing to a wide range of audiophile needs in our Premium, Grand and Reference Series of products. The new true wireless noise-cancelling headphones open the door to a wider and younger audience for appreciating high-quality sound on the go.

DL: Besides the SL-1200 turntable, what are some other iconic and significant Technics products from the past?

BV: There were so many, I’m not sure where to start. It’s a little-known fact that the first Technics product introduced in 1965 was actually the Technics 1, a 2-way bookshelf loudspeaker, not a turntable. The first Technics turntable was the SP-10 and introduced direct drive to the world in 1970. It enjoyed similar status as the latter SL-1200s among professionals and audiophiles with a number of model changes and improvements over the years. Another turntable “first” was the SL-10 linear tracking (LP jacket-sized) turntable which could play [oriented either] horizontally or vertically.

SP-10, the first direct drive turntable.

In 1981, even before CD, Technics pioneered PCM digital recording on VHS tape in an all-in-one deck (PV-M100), which was available in a two-piece portable and a processor-only version. This was originally a 14-bit process that I felt was quite enjoyable and convenient to use. There are [actually] many highly-regarded companies that specialize in refurbishing the legacy turntables and open reel decks to bring them back to original or improved specs. Some of these are: J-Corder for open reel tape decks, KAB Electro Acoustics, OMA and Artisan Fidelity who specialize in turntable upgrades and modifications.

DL: The Panasonic DP-UB9000 4K Blu-ray player is widely considered the best player available, filling a void left by Oppo going out of business while providing noticeably better video reproduction. When I began my review of the Technics SL-G700 network/SACD player it reminded me of the UB9000, because both components are heavy, flawlessly finished and feel like they are machined from a solid block of metal. My impression was that the UB-9000 and SL-G700 could be sister products, despite the different purposes, brand names and likely different engineering teams responsible for their design. Is there any commonality between Technics and Panasonic besides having the same parent company, and do you think we will ever see high-end Panasonic audio products, or high-end Technics video products?

BV: As you point out, Technics is and has always been a subsidiary of Panasonic, without whose technical, manufacturing and financial prowess could not have produced the Technics product line we know today. Digital technology plays a major part in all the product designs and is shared among the Panasonic Consumer and Professional divisions, whether appliances, entertainment (TV, video, Technics, audio, headphones), Imaging (Lumix, cameras, lenses), computers, and even personal care and other products.

A good example is the motor control system used in the new turntables which borrows a digital speed control mechanism designed by the Panasonic Blu-ray team. As far as crossover products, my guess is that Technics will continue to carry the high-end audio flag and this philosophy already plays a part in the sound quality of Panasonic’s flagship OLED TVs.

DL: Are you finding that customers purchasing Technics components are using them in all-Technics systems, or are they mixing and matching as audiophiles typically do?

SU-GH700 Grand Class integrated amplifier.

SU-GH700 Grand Class integrated amplifier.BV: I would say that most customers’ systems evolve by mixing and matching. It’s rare for a system to be all one brand. However, it has been recognized by a well-known audiophile publication that our flagship R1 Reference System offers what they deem to be award-winning synergy as a complete system. I feel a similar appreciation for the new more affordable Grand Series which offers incredible audiophile value and great synergy and convenience when used together as a system.

DL: Your brick and mortar dealer network is still somewhat small, and I frequently receive e-mails from readers of my “Sound Advice” newspaper column who can’t find a dealer in their hometown. Do you have plans for expansion in this area? And what do you look for when selecting Technics dealers?

BV: It’s a long road to re-establish a product line even with the brand strength of Technics. It’s difficult to capture position in a dealer’s showroom as there are plenty of competitors. In the last five years I believe Technics has earned its place back in audiophile circles and will continue to grow market share and add new dealers. Although we’ve gained ground, we’ll likely never experience the top tier sales volume enjoyed in the 1970s through the 1990s. I like to say we’re not our father’s Technics. We’ve progressed cautiously using proven conservative methods to utilize the support of hi-fi and Professional DJ specialists in order to present the fine subtleties of a new, much higher-priced and technically-involved product line. But as the product line has grown we have added more and more dealers. And as we develop more affordable and mainstream (regarding ease of use) products, it will lend to more e-commerce thus more national reach.

DL: Please explain the difference between Technics’ Premium Class, Grand Class and Reference Class products.

BV: Premium Class is our entry-level audiophile line, which includes products like our SL-1500C turntable, SB-C700 loudspeaker and Ottava wireless speakers. The Grand Class, which is growing in popularity, offers advances in digital amplification, high-resolution audio processing and streaming and also includes turntables like the SL-1200GR, SL-1210GR and others. A Grand Class system comprised of the SU-G700 integrated amplifier, SL-G700 networking CD/SACD player, SL-1200GR turntable and SB-G90 coaxial loudspeakers, sells for $12,200 and I would put it up against anything even at twice its price. The Reference Class offers our flagship power amplifier, control preamp and the SP-10R and SL-1000R turntables.

DL: Anything else you would like to add?

BV: Probably not; my wife says I talk too much! 😉

Technics/Rediscover Music

2 Riverfront Plaza, 8th Floor

Newark, NJ 07102

201-348-7000

www.technics.com/us

All images used with permission of Technics. Header image: SL-1100 turntable, circa 1971.

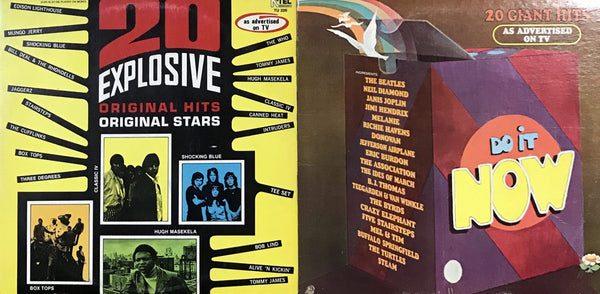

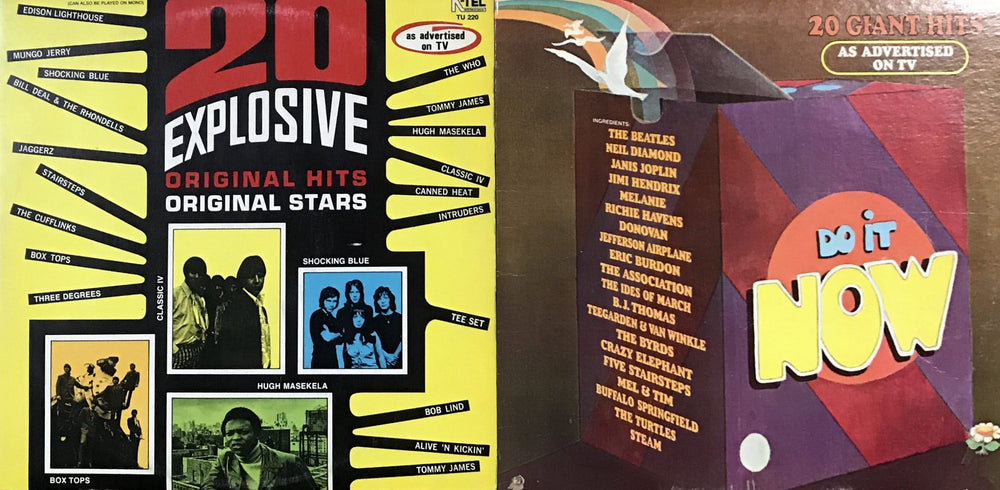

K-tel Records: Now That’s What We Call Music!

Since the late 1990s the Now That’s What I Call Music franchise has almost single-handedly kept compact disc sales from completely falling off the ledge. The concept is a simple one. Each album compiles a roster of current hit songs into a single release. For almost 40 years these music compilations have delivered the kind of sales performance that equaled what you might expect from a hit record back in the gravy days of vinyl. The most successful volume to date is 1999s Now That’s What I Call Music! 44. This edition has sold 2.3 million copies and remains the biggest-selling various artists compilation album in the UK. 2008s Now That’s What I Call Music! 70 sold 383,002 units in its first week of sales alone. Today the series is simply called Now and volumes are produced in over thirty countries worldwide.

What’s most surprising about the Now franchise is that it was never a new or novel concept, even if it was treated as one. The business model had made millions for others before Now arrived, with the most popular being the very concept’s own creator, K-tel Records.

K-tel was founded by Canadian Philip Kives, a salesman who started his career selling cookware, iceboxes and other items and pitching wares in Atlantic City. In 1962 he hit upon the idea of selling a Teflon-coated frying pan on TV in what would eventually become known as the “infomercial.” Kives later expanded into selling other items, including the famous Dial-O-Matic and Veg-O-Matic food choppers!

In 1966, K-tel released its first compilation album, 25 Country Hits. It quickly sold out and prompted the K-tel follow-up, 25 Polka Greats. This one sold 1.5 million copies in the United States alone. The hits kept coming and included The Super Hits series, The Dynamic Hits series and The Number One Hits series. K-tel assembled greatest hits from the latest, greatest artists in one single package. There were even thematic compilations like Goofy Greats, Super Bad, Super Bad Is Back, Souled Out, Summer Cruisin’, and a 1950s look back, Rock n Roll Show.

The K-tel music compilations were a quick, very cheap way to boost your music collection or hear your favorite pop hits on demand. A record could go for $3.99. The commercials were kitschy and brilliant. During the 1970s and 1980s these catchy broadcast advertising spots were impossible to miss, and they helped define that era’s television experience. For the voice overs, Kives hired Bob Washington, the morning man of CKRC-AM, one of Winnipeg’s three Top 40 stations. Back in the day Washington’s voice was as distinct as the K-tel ad copy he would read. I can still hear him voice, “Twenty-two original hits! Twenty-two original stars!” and the tagline which was always some variation of, “LP, $4.99! Tape or cassette, $5.99!” These ads remain one of the many great pop culture memories I have from my youth.

But it wasn’t all great. In order to squeeze as many hits as they did into a single record (often eleven per side) K-tel often cut songs down, making them shorter than their original run time. And no song would run any longer than 2:30. In order to secure the rights to the bona-fide hit records, many labels forced K-tel to also accept lesser-known songs as part of the licensing deal. That would always lead to some head scratching as you browsed through a particular record’s playlist. Even on some of the ads where the actual bands spoke about how “explosive” a collection was, you could see them grimace as they called out some of these wild card additions.

The records weren’t of high quality either. They were terribly thin so the grooves couldn’t be cut deep. This impacted the sound quality. The bass was weak, the midrange was gritty, and the high end often entirely absent. The grooves were also cut very close to each other, making even the smallest scratch a guaranteed spot for the record to skip with each spin. In a way we all accepted the poor production quality because when you got right down to it, the record was really a sampler. Anything that caught your ear was probably going to prompt you to go out and buy that band’s actual record. Considering how important sound fidelity is to me to Copper readers it’s a wonder that even back then we would have been all that forgiving of the products’ shortcomings.

Competitors quickly emerged, with Ronco Records being perhaps the most noteworthy. Founded by fellow TV demonstration salesman Ron Popeil, Ronco was a company that was more diversified than K-tel, with a portfolio of household and other products that gave them better financial stability. (Who can forget classics like the Pocket Fisherman, GLH-9 spray-on hair and that favorite of budding audio engineers everywhere, Mr. Microphone?)

In 1972 Ronco released its first compilation, 20 Star Tracks. This was soon followed in 1973 by the That’ll Be the Day soundtrack. Rock worked for Ronco, but it was with disco where they would set themselves apart and really take off. Disco Daze and Disco Nites were among their best sellers. Maybe even more famous than their compilations was their announcer, Tommy Vance. A UK native, he was not only the voice for all Ronco products, he had an illustrious career as a radio broadcaster, and announced each act that took the stage at Wembley Stadium for Live Aid in 1985.

Even CBS records got in the game with their CSP (Columbia Special Products) division. To this day I find myself still spinning their compilation #1 Rock Hits of the 70s. It has very few “rock” songs but across eighteen tracks it delivers Freddy Fender, Billy Swan, Andy Kim, The O’Jays, The Manhattans and more. I love the mix so much that I had to make a digital playlist counterpart to back me up for that day when the record becomes completely played out.

Then there were the companies that recorded sound-alike covers of the actual hits. These sounded very close to the originals but as soon as you picked up what was really going on the record became unlistenable. It’s amazing how long this racket actually lasted.

The editor will not admit to having these records in his collection.

The editor will not admit to having these records in his collection.As competition from others like Ronco grew, K-tel diversified, forming subsidiaries in areas such as real estate and oil exploration. In 1980 they acquired rival Candlelite Records. This was a bit off-strategy asCandlelite focused on music from the 1940s and the easy listening genre. The audience for this music was older and this turned out to be a losing investment.

In the 1980s the tide continued to turn for K-tel International and in 1984 the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. K-tel would negotiate settlements with the banks and other creditors and seven years later, in 1991, Kives once again became K-tel’s owner. By then, the Now franchise had been well underway, having land-grabbed the compilation business from K-tel and all others in the market.

K-tel still exists, even if they are no longer the music powerhouse they once were. That said, they distribute more than 200,000 songs worldwide each year through digital platforms and receive revenue from licensing songs for commercials, TV and movies. But back in the day, they were as Forbes magazine once said, “the Spotify of the 70s.” K-tel records were easy go-to spins for those afternoons when friends came by to visit. Putting a K-tel record on was a sure-fire way to please almost anyone.

Years ago as an employee of Time Inc., I took advantage of the great deals they offered employees at their company bookstore. I decided to buy the entire 1970s series called AM Gold, 10 CDs of AM radio at its 1970s best. We also developed a similar compilation line at Entertainment Weekly that began as a subscription tool and then grew to be a fantastically successful business on its own. Curated by a former circulation manager named Vinny Vero, the collections caught fire quickly and proved that great mixes, whether on vinyl, cassette, CD, digital file or streaming, connect with us in ways that are physical, emotional, and in the undefinable region between both. This is something that Philip Kives picked up on and turned into a sensation.

As I look back now I realize that we all found bands through K-tel that we might not otherwise have paid much attention to. Foo Fighters frontman Dave Grohl famously said that he discovered Edgar Winter through a K-tel compilation record. I discovered Redbone (“Come and Get Your Love,” “The Witch Queen of New Orleans”). An entire generation discovered that sharing music was maybe K-tel’s greatest gift to us all. Better yet, that lesson came at the everyday low price of $3.99 per record. “Explosive” indeed!

There Must Have Been Something In the Water

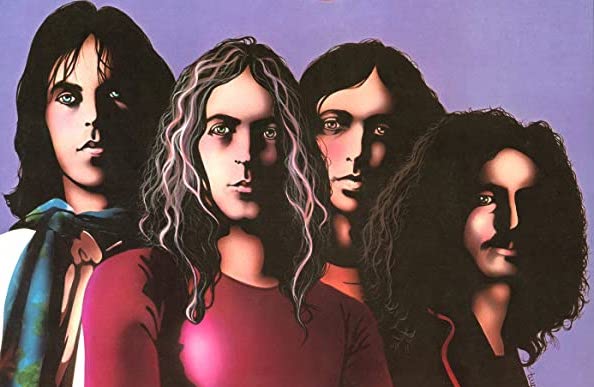

If the Beatles never happened, if the British Invasion never occurred, then music fans around the world would more than likely never have been exposed to some of the finest white blues singers the UK produced between 1964 and 1970.

Note…this list only covers the time frame from 1964 – 1970 and only British singers!

There are always caveats and guidelines with any list like this so here are mine:

As great as John Lennon and Paul McCartney were and are as singers (among my all-time faves), they were never blues singers, notwithstanding John’s vocals on “Twist & Shout,” “Please Mr. Postman” and “This Boy,” and Paul’s on “Oh Darling” and “Helter Skelter.”

They were/are incredible rock n roll and pop singers.

There really is a difference in singing styles even though both blues and rock are steeped deeply in Black blues vocals.

Mick Jagger may cast himself as a blues singer but to me, as good as he is in the way the Stones do their versions of Chicago blues songs, Jagger just ain’t a great blues singer and is not on my list. Jagger does the Stones perfectly and he’s done wonders with his very limited range but in truth, the Stones were a better blues band than Jagger was a blues singer during the time that they were a blues cover band.

Neither are Elton, Bowie, Ray Davies, Freddy, Roger Daltrey or Frampton blues singers stylistically.

Also, Pink Floyd may have started out as a blues band — they were named after two blues singers, Pink Anderson and Floyd Council – but Syd Barrett (love him!) and Roger Waters were never blues singers.

You either get where I’m coming from or you don’t and I’m ready to hear your comments so bring ’em on!

One more thing…

Most of you will know these British singers. I have read multiple interviews with most of them over the last 50 or so years. They all share similar stories, which led to the idea for this article. All of these English singers, along with countless other musicians, somehow started to hear American Black music on the radio late at night or on the 7-inch 45 RPM singles given to them by a family member or family friend who brought them back from the US. The music resonated with these musicians in ways that can only be described as culturally connected, and all happening at the same time!

Most of the singers cite very similar influences such as Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, J.B.Lenoir, Memphis Slim, Big Mama Thornton, T-Bone Walker, Big Bill Broonzy, Sunnyland Slim, Lonnie Johnson, Big Joe Turner, Sonny Boy Williamson, John Lee Hooker and Willie Dixon. I could go on, but the thing to know is that if you love this stuff and want to know more about it, there are a couple of Grammy-winning DVDs called The American Folk Blues Festival 1962 – 1966 that feature all of these performers plus many more. The performances are from a series of German TV shows that were filmed during the time. These artists were treated so well in Germany that many of them didn’t want to return to the US. Memphis Slim moved permanently to Paris and Sonny Boy Williamson stayed in England for a while and joined the Yardbirds for an album.

These discs provide an amazing “CliffsNotes” version of this purely American musical art form.

Just about every blues legend alive at the time performed. (You’ll have to deal with the fact that some of the TV stage settings look like slave quarters. I’m sure the producers thought this was going to lend some kind of air of “authenticity” and need to be seen in context.) The two young Germans who produced this event clearly loved these performers. The DVDs were produced for commercial release by Experience Hendrix, the licensing arm of the Jimi Hendrix estate run by his sister Janie Hendrix.

OK, here goes:

After the arrival of the Beatles in the US, the next British Invasion (referred to as “BI” from now on) band to smash into our shores Beatles was the Dave Clark Five. Although they didn’t have their first number one for a year and a half (late 1965 with “I Like It Like That”), one knew right away that the lead singer Mike Smith was incredible. His vocals on “Glad All Over,” “Bits and Pieces” and “Because” were incredible but on the track “Baby, You Got What It Takes” he totally crushes it.

The first BI band to have a number one record on the US charts after the Beatles were the Animals in August, 1964. The world got to hear Eric Burdon for the first time in his without-a-doubt definitive version of “House of the Rising Sun.” Time after time, with successive hit after hit like “We Gotta Get Out of This Place,” “It’s My Life” and “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood,” Eric brought it! [See Ken Sander’s article on hanging out with Eric Burdon in Issue 109 – Ed.]

Next up, another then-new band, Manfred Mann with “Do Wah Diddy Diddy.” That vocal blew through the AM airwaves like a jackhammer. The singer of that track was Paul Jones. Jones was replaced a year later but everyone who grew up with radio from that era knows how amazing that vocal was.

By late 1965 the world heard about John Mayall and his band The Bluesbreakers. Although Clapton was the star of the Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton record, Mayall’s blues voice became synonymous with the British blues scene and anyone who was anyone in that circle owes their success to the exposure of the genre given by Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. Listen to the track “Have You Heard” from that debut album and you will understand how good he is.

Special mention goes out to Alexis Korner and Long John Baldry who were UK legends but never really made it in any commercial way over here, except maybe for Long John Baldry’s “Don’t Try to Lay No Boogie-Woogie on the King of Rock and Roll.” It was all over the New York FM airwaves in 1971.

Van Morrison also came into the picture in late 1965 with the band Them. They covered the garage band hit “Gloria.” Maybe you didn’t know about him until “Brown Eyed Girl” two years later. Van has one of the great soul voices of all time and when you hear Van…you know it’s Van!

In October 1966 the US AM airwaves once again were shaken to the foundation with the vocal of 18-year-old Stevie Winwood on the Spencer Davis Group hit “Gimme Some Lovin’.” One of greatest debut singles in BI history.

Stevie went on to front Traffic, who scored an enormous hit with “Dear Mr. Fantasy,” and two years later joined the short-lived Blind Faith, considered one of the first rock “supergroups” thanks to Winwood and bandmates Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker and Rick Grech. Listen to Winwood’s vocal on “Presence of the Lord” on their one and only release, Blind Faith. It’s hair-raising. Years later he gave the world “Higher Love.” His live version of Ray Charles’ “Georgia on my Mind” will bring you to tears.

When John Lennon was asked what his favorite song was in 1967, he not only did not mention any of the Beatles songs from Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, his immediate response was “Whiter Shade of Pale” by Procol Harum. While technically “Whiter Shade of Pale” wasn’t the number one song in the US that “Light My Fire” was, it ruled over everything in my book as well as in the UK which is why Lennon said what he said. There was so much amazing music that year: Hendrix bursting onto the scene with Are You Experienced, the Doors debut, Love’s Forever Changes, the Grateful Dead’s first album, Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow, Moby Grape’s first album Omaha, Country Joe and the Fish, Big Brother and the Holding Company…the list goes on and on.

Yes, 1967 was a watershed year for great music but “Whiter Shade of Pale” dominated the US and UK charts for a while and the lead vocal by Gary Brooker has become one of the all-time classic vocals in pop music history. Procol Harum had many other FM radio hits (“Shine on Brightly,” Simple Sister,” Whiskey Train”) but only returned to the pop charts in 1972 with a live version of “Conquistador” performed with the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra.

As I go down this list I am amazed at what this short period of time brought us from the UK.

If just the above was all of it, that would have been incredible enough, but the decade wasn’t over yet.

1968 brought the release of The Jeff Beck Group’s debut album and gave the world lead vocalist extraordinaire Rod “The Mod” Stewart. The album opened with the Yardbirds hit “Shapes of Things.” Rod’s vocals almost blew my stereo apart. Nothing more about Rod needs to be said as his recorded history with the Faces and as a solo artist speaks for itself.

Maybe some of you don’t know much about Steve Marriott. Many consider him one of the greatest English blues singers of them all. He started out with the Small Faces, a very English mid-sixties pop group (see Anne E. Johnson’s article in Issue 117). He left them in 1968 and, along with Peter Frampton, formed Humble Pie in 1969. Along with Blind Faith, they became one of the first supergroups and many consider them, along with the Jeff Beck Group, the founding fathers of heavy metal. [We could add the MC5 and Blue Cheer. – Ed.] Steve’s vocals on the Humble Pie album Performance Rockin’ the Fillmore cemented his superstar vocal status. Later, Humble Pie’s performance opening for Grand Funk Railroad at Shea Stadium blew GFR off the stage.

1969 also brought us Tons of Sobs, the debut album from Free with lead singer Paul Rodgers. The song “All Right Now” came two years and two albums later, but their 1969 debut tour, opening for Blind Faith in the US, was legendary, as “The Hunter,” the first single off their debut album, was written by the members of Booker T & the M.G.’s and that vocal tells you all you need to know about how great Paul Rodgers is. Add to this the multi-platinum success of him leading the entire Bad Company era, and you have a world-class singer whose only misstep was his short stint as Freddie Mercury’s replacement in Queen. Paul’s voice just didn’t fit the Queen songs and it was even weirder seeing Queen playing Bad Company songs!

Closing out this incredible decade was the 1969 debut album from Led Zeppelin. Zeppelin has become second only to the Beatles in total US album sales by a British rock group. As pretty much everyone reading this knows, Robert Plant’s vocals on that debut album are astounding. His blues-based vocal stylings owe much to Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker and T-Bone Walker, to name just a few.

I was fortunate to have been at many of the shows given by the artists listed above. I was in the front row at Led Zeppelin’s first-ever show in New York City, at the Fillmore East on January 28th 1969. Plant, in a show of his incredible lung power, held the microphone away from his face and sang alone, a cappella style, to the sold out crowd during a quiet part of the song “You Shook Me.” The place went crazy. I have never seen a vocalist with that much power before or since.

That’s my list. I have no doubt many of you will offer up your own. All I can say, again, is that if the Beatles never happened, we might never have gotten to hear these incredible blues-based singers from the UK.

Header image of Steve Marriott courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Dina Regine.

An Audio Journey

Copper reader Adrian Wu lives in Hong Kong and has spent time in the UK and elsewhere, as you will see. He is a contributor to the Asia Audio Society website, dedicated to reference-quality sound and reproduction. As you will also see, Adrian, like so many of us, has had quite an audio journey, which he is kind enough to share with us and which we will run in two parts, to be concluded in Issue 121.

I would like to say thank you to everyone involved in Copper. For me, this is the one true magazine for music and audio lovers, devoid of commercial interests and packed full of practical information, learned opinion and thought-provoking comments. Looking back at my audio journey of almost 40 years, I have made many friends and continue to learn new things every day that I will treasure for the rest of my life. And I get to use the stuff I learned in my physics and math classes at school!

I have been a music lover all my life. I started learning the piano at the age of eight, and I was very fortunate to encounter my second teacher after I started boarding school in the UK. He was a retired concert pianist with a mind-boggling repertoire, but he also taught me a lot about how to be a decent and honorable human being. From that day on, music became a major focus of my life.

My introduction into audio came after I joined the electronics club organized by my high school physics teacher. One day after our club session, he asked for volunteers to help him with a project in his home. My friend and I volunteered, and that was the first time I laid my eyes on the Quad ESL electrostatic loudspeaker (or any audiophile equipment for that matter). At the time, the ESL was still available new from the factory, but being a high school teacher, he could only afford a second hand pair. He wanted to upgrade the EHT power supply unit, and we helped him remove the covers. Not having allowed them enough time for their membranes to adequately discharge, he stuck his hand in and was promptly thrown back several feet onto his butt by the 6000 volts (thankfully of high source resistance) still lurking around. Having witnessed this debacle, I knew that instant that these were the speakers for me.

During my university years living in Edinburgh, I eagerly awaited every new issue of Hi-Fi News & Record Review. I saved up my allowance (not having a girlfriend helped) and bought my first stereo, which was made up of the Dunlop Systemdek II turntable (aka the “pressure cooker”), Mission 774 arm (designer John Bicht’s classic) and Audio-Technica AT33 cartridge. Amplification was an Arcam integrated, driving KEF Coda 3 speakers. A Frenchman operated a used record store at his wine shop in New Town, and I bought the wide- and narrow-band Deccas (the wide band issues were the early premium releases, including the whole SXL2000 series, and the early SXL6000 series from 1962 until 1970. These were mostly produced with tube electronics. The later SXL6000 narrow band issues were all produced with solid state electronics), EMI ASDs and SAXs, French Pathé Marconis and Lyritas etc. that nobody wanted because the CD offered perfect sound forever. As the Scots were frugal and took great care of their possessions, the LPs I bought were mostly pristine. These still make up the core of my record collection. I investigated CD audio, and decided it was not for me. CDs cost 10 pounds in those days, whereas I could pick up a mint second hand Decca LP for about 2 pounds.

My classmate Neil was a Linn evangelist. After he saved up enough money, we went to the Linn dealer in Edinburgh to audition the Linn Sondek LP12 turntable. The salesman (barely out of high school) was shocked that someone wanted to actually listen to the thing. What was the point of auditioning since the product’s superiority was cast in stone? He took one out of storage, got it out of the box, plonked it on top of the box, hooked it up and put on a record. It might have been Steely Dan’s Gaucho if I remember correctly.

The record player had an Ittok arm and a Karma cartridge, top level in those days, but we could see the suspension bouncing in every direction except vertically. The cartridge mistracked every few revolutions and the sound was awful. After a few minutes, my friend leapt up from his seat and exclaimed, “That’s wonderful. I want one now.” And he parted with his cash, hard-earned during years of summer jobs (and no girlfriend), just like that. Talk about Ivor worshipping! The next time I visited Neil, he proudly played his copy of Gaucho through his officially approved system consisting of the LP12 with Naim Nait electronics and Linn Kan loudspeakers.

I credit Mr. Winston Ma (better known outside Hong Kong as the founder of the record label First Impression Music) for my early education in all things audio. During my holidays when I would go back to Hong Kong, I loved to hang around his shop, Golden String, in the Central business district. He was already very well-known and well-respected within the industry in those days, but he and his staff would spend hours explaining things to me, someone who couldn’t even afford the cheapest merchandise in his shop. He was the agent for brands such as Cabasse, Burmester and Koetsu, not exactly equipment that a university student could aspire to buying.

One day, a customer walked into the shop in the middle of the afternoon. He was dressed in the type of clothes worn by men who pulled rickshaws and by dock laborers, and he was wearing dirty old canvas shoes (way before those became fashionable). He did not know who Mr. Ma was, but nevertheless, Mr. Ma greeted him warmly and spent a lot of time introducing him to various products. At the end, he pulled out a pile of cash from his pocket and bought a top Koetsu cartridge. I was totally amazed and said so to Mr. Ma. I will always remember his response. “To be successful in selling hi-fi is no different from what you need to do to be successful in life,” he said, “and that is to treat everyone as equal and with respect, no matter if you think they are rich or poor, smart or dumb, well or poorly educated.” This advice has served me well.

Many years later, after he had emigrated to Seattle, we worked together on a project to release a series of recordings I had made for a Chinese violin prodigy (and that is another long story). Unfortunately, this project did not come to fruition due to his illness and untimely demise. I still go past that building from time to time, and the large window on the first floor is still the same after 35 years, only without the large Golden String logo. It still brings back fond memories.

After graduation and actually living off the fruits of my own labor, I saved enough money to buy an “antique” Bösendorfer (1928, to be exact) piano. A few years later, I sold my original system to a friend (who had been coveting it for some time), and upgraded to a Roksan Xerxes turntable with Artemis arm, Mission Cyrus integrated amplifier and Linn Tukan speakers. A chance encounter led me to move to the US for postgraduate training. I arrived with just a suitcase and rented a studio apartment, the only criteria being that it was large enough to accommodate my piano.

I bought a futon that folded into a sofa, which was the extent of my furniture. Fortunately, my piano arrived soon afterwards, having been sent away ahead of time for an overhaul, and then directly from the workshop to my new address. It also became my writing desk and dining table for the next year.

I was afflicted by the common audiophile malady of upgrade-itis, and soon ditched the Cyrus (since it had no option for 110 volts and needed a transformer to operate in the US) for a used conrad-johnson PV10a preamplifier (tubes!) and Aragon 4004 power amp. I didn’t go for a tube power amp after considering the potential maintenance cost. Being in an extremely busy job with a brutal call schedule meant not much time for music, but I did manage to start taking weekly piano lessons from a professor at The University of California, San Diego (and falling asleep during the lessons). She (in fact, her husband) had extremely impressive wall to wall shelves loaded with LPs along the corridor and the living room.

Another six years went by, and after landing an academic job back in Hong Kong, I moved back after having been away for 19 years. I soon picked up old friendships and made new ones. An old family friend introduced me to someone who had been into music recording since he was at university in Los Angeles during the late 1970s. Having known noted recording engineer and producer Allen Sides for a long time, he had a nice collection of vintage microphones (being a top investment banker in Hong Kong helped) and recorders. We could therefore play with his Neumann U47, U67, M49, M50 and AKG C12 mics, and even a mint condition Telefunken ELA-M251.

My new friend also needed a few able bodies who were willing to help him haul around tons of equipment. Together with another friend (a real estate guy) who had set up a mastering studio to keep himself amused, we managed to get a contract (pro-bono) with the Hong Kong Philharmonic to record some of their dress rehearsals and concerts for their archives. (Their employment contracts with musicians in those days excluded permission to make commercial recordings.)

We would set up the microphones early in the morning (usually on a weekend) for the afternoon rehearsal, and then the evening concert. We usually limited ourselves to eight microphones (to lighten somewhat the back-breaking labor), arranged in a “Decca tree” configuration behind the conductor, with two flanking mics and a few spot mics for the percussion, basses and wind instruments depending on the program. At my friend’s urging, I found a Nagra IV-S stereo analog recorder with a QGB 10.5-inch reel adapter in a BBC sale in London for 2,000 pounds. Another 800 francs for new heads and a once-over at Nagra, and it was good to go. I was also offered a Telefunken M21 tape recorder for 800 Euros, which I turned down due to a lack of space. They were throwing these out of radio stations in Europe to replace with DAT machines in those days. Apparently, the same stations were buying them back a few years later when they realized that some of the DAT recordings were having dropouts and becoming completely useless. I would have bought a Studer A820 deck if I had space; they didn’t go for that much in those days! We would feed the mics into a Studer analogue mixer, and the stereo out into a splitter to feed our two Nagras, and line level outputs from the mixer would be fed to a digital multitrack recorder for use by our real estate friend. For monitoring, we used active Tannoy loudspeakers.

All that ended when the now-current director of the orchestra came in and did not want to continue with the arrangement, but it was fun when it lasted. At least, we got almost all the Mahler symphonies on tape (but not the 8th, sadly).

Back on the hi-fi front – the subchassis of my Roksan turntable warped after less than a year spent in Hong Kong. Apparently, this was a common problem in humid climates. Therefore, off I went to buy a new turntable from Excel Hi-Fi (now defunct), the biggest dealer (at the time) in Hong Kong. I decided to buy a Michell Orbe turntable with a Graham 2.2 arm and Lyra Helikon cartridge. The salesman was an industry veteran whom pretty much every audiophile in Hong Kong knew. When I enquired if he was going to set up the player for me, he sneered and said, “if you can’t set up a turntable yourself, you shouldn’t be in this hobby!” Having had 15 years of experience with turntables by then (and still having reasonable eyesight), I could of course set up the rig, but I expected some service after having spent that much money (which was of course peanuts from his perspective). In any case, we became good friends nevertheless, even though I never bought anything else from the shop.

After some time I was able to buy a flat. I finally had a chance to indulge in my childhood dream – the Quad ESL! During a trip to visit my sister in Leicester, England, I came across an ad in the local newspaper for a pair of Quad ESL loudspeakers and Quad II amplifiers. I borrowed my sister’s car and drove to meet the seller at a council estate. The ESLs were in excellent cosmetic condition, and at a very low price (something like 200 pounds). The amps were a bit beaten up but the price was also low. I bought the whole lot and spent the next few days packing them up to ship back home.

After the gear arrived at my home, my old electronics skills came in handy. I went shopping for a soldering station, oscilloscope, multimeter and tools. My recording partner was a wellspring of information, having been introduced to the world of vintage audio by his friend, legendary audio publisher and manufacturer Jean Hiraga, and having a collection of vintage gear to rival his mic collection (Western Electric amps, tubes, drivers and transformers etc.). He came over and we checked out the speakers. The voltage was weak, and the panels had faded. I therefore had to order new EHT units and panels from One Thing Audio, and the two of us rebuilt the speakers over the Easter holidays. The hardest part was installing the panels, and having to remove uncountable numbers of splinters from my fingers afterwards.

The amps were in their original state, which means wax leaking out of the transformers and components with badly drifted values. When researching about restoring these pieces, I came across a local chat group that provided a lot of information. I made friends with the administrator Tim, another banker. He is a walking encyclopedia of vacuum tubes and vintage hi-fi, especially British products, since like me, he went to boarding school in the UK. He can recite all the structural variances of different vintages of most of the common audio tubes from Mullard, Telefunken, Amperex and so on. He is a great one to consult on the authenticity of NOS (New Old Stock) tubes. He and two partners own a vintage hi-fi shop called Vintage Sound, which is really an excuse for them to buy stuff. Tim had collected pretty much every make and vintage of the classic BBC LS3/5a studio monitor speaker over a couple of decades (another anomaly of British audiophiles of our vintage, thanks to Ken Kessler), including a pair of rare prototypes with screwed-in back panels, until thieves broke in and stole the whole collection one weekend. They didn’t steal anything else, not even the rare tubes in the display cabinets. I guess they were too busy trying to remove the haul without being caught. I had never seen my friend so distraught, and he spent the next few years going around the second hand shops in Hong Kong and Guangzhou trying to buy back whatever he could.

In his shop, I have experienced some of the weirdest and most wonderful things: Quad corner horn loudspeakers, Lowther back-loaded horns, the original Williamson amp with Partridge transformers as well as pretty much every amplifier ever made by Leak, Radford and Pye, and all the vintage Tannoy drivers (one of his partners’ nicknames is “Tannoy Silver”).

One of the friends in our group was a German named Dieter. Dieter started working at Siemens when he was still in high school (his mom worked in the vacuum tube division of AEG), and stayed with the company until his retirement as the general manager of its medical business in Hong Kong ten years ago. A properly trained electronics engineer (meaning he studied vacuum tubes and analogue electronics), he had kept a copy of any datasheet, manual and schematic that he had ever come across at work, filed away in the typical meticulous German manner. He could recite off the top of his head the specifications of many Siemens tubes and parts. He had an enviable collection of C3M, AD1, EL156, F2A11 and other rare tubes, as well as Sikatrop capacitors and other vintage parts, and introduced these to me via the lovely amplifiers he built in his spare time. Sadly, he left Hong Kong and went back to Hamburg after his retirement, rented a garage and started rebuilding vintage Mercedes sports cars.