Loading...

Issue 112

Tiptoe Through the Tweeters

Vinyl and Absolute Polarity: Q&A

Bob Lehman, a classically-educated retired electrical engineer and long-term audiophile, asked some very good questions upon reading my column in Issue 110, “Vinyl and Absolute Polarity: A Technical Exposition.”

What follows are my detailed answers to his questions, combining science and practical examples to hopefully keep it interesting both for engineers and for normal people!

Bob Lehman: All magnet-and-coil acoustic-to-electrical transducers [including] dynamic microphones (I’m not sure about powered or electret condenser types), tape heads, and most phono cartridges (moving magnet, moving coil and moving iron I believe, but again, I’m not sure about electret condenser types) produce their electrical signal as a function of (i.e., in proportion to) the rate of change of the mechanical motion of the moving part of the transducer – right? E.g., my old Shure test record, for the trackability sections would announce each [section] with a phrase such as “velocity 5 centimeters per second, frequency 1,000 Hertz.” For that example, the velocity is a reference to that of the vibrating stylus – right?

J.I. Agnew:

Both mechanical grooved-media reproducer (record player/phonograph) and magnetic media reproducer(tape machine) transducers respond to the rate of change of mechanical displacement or magnetic flux. When motion is stopped, such as keeping the needle down on a stationary record, or having a tape machine in “edit” mode (tape stationary, head in contact, reproducer electronics activated), there will be no signal output from the transducer. There may still be a non-zero value of absolute groove displacement (relative to the spiral pitch or depth), or magnetic flux, at the point of contact between transducer and medium, but the transducer will not produce any output.

On magnetic tape transducers operating on the Faraday principle (as is the case with most common tape heads), this is because the electrical output is generated by a coil wound on a core of a suitable magnetic material, which generates an electrical signal when the flux through the core changes. Mathematically speaking, a periodic change of any parameter (displacement, flux, etc.) has a certain frequency of repetition and therefore different values over time. A static value (no rate of change) has a zero frequency of repetition.

The operating principle of magnet-and-coil transducers can be mathematically expressed as e = N (dφ/dt), where e = electromotive force (EMF, or voltage), N = number of turns of a coil linked by magnetic lines of flux, φ = flux and t = time. If the flux is constant, then regardless of its numerical value, the rate of change of flux over time (dφ /dt) does not exist, which will always result in e = 0. Zero voltage effectively means no signal output.

As such, if non-zero flux on tape remains stationary in front of the repro head, the core would assume an equivalent non-zero value of DC magnetization, but since the frequency/rate of change would be zero, there would be no electrical output. A Hall-effect sensor (a device used to measure the magnitude of a magnetic field), on the other hand, would be able to detect DC magnetization, which is why Hall-effect probes are commonly used in instrumentation for measuring permanent magnets, and Faraday-principle heads are used to reproduce audio. Faraday principle tape heads cannot be used to measure the magnitude of a permanent magnetic flux. Once the tape starts rolling, the flux keeps on changing and the rate of change is converted to an electrical signal, since dφ/dt exists.

Phono cartridges have more effects at play. The Faraday principle of coil EMF (electromotive force) applies just the same as for tape heads. But as this is a mechanical medium, the electrical output is proportional to ds/dt, where s = stylus displacement. Inside the cartridge, however, the mechanical displacement moves a magnet (or coil) relative to a coil (or magnet), creating a dφ/dt, (variations in flux linking the coil, over time). Relative motion between the magnet and coil at f ≠ 0 introduces a rate of change which produces an electrical signal. On the other hand, when the cartridge is lowered onto the record, the vertical tracking force will result in cantilever displacement. If lowered on a stationary record, this displacement is static, and despite the magnet inside the cartridge still causing a non-zero value of flux, dφ/dt does not exist (there is no difference in the value of φ over time).

Initially, at the moment it drops, there will be a short impulse where dφ/dt exists. But then it will reach an equilibrium where dφ/dt no longer exists and the displacement depends entirely on the static compliance (in μm/mN) of the cantilever suspension and the effective vertical tracking force (in mN). This static displacement does not produce any output from the cartridge. This is not a sudden effect; the output starts dropping gradually below a certain frequency. By 0 Hz (DC), it is certainly zero. But it already starts dropping at a frequency defined by the transducer design parameters.

This is because in a practical cartridge, the rate of change of flux does not remain proportional to the rate of change of displacement, at large amplitudes of displacement, due to finite magnet dimensions, weight and strength.

Especially below the lower 3180 μs/50.05 Hz RIAA curve point, where the recording is in constant velocity mode, the amplitude of displacement increases as the frequency decreases. As amplitude increases, the time interval also increases in proportion (being the inverse of frequency), keeping the velocity (ds/dt) constant.

The flux swing increases along with amplitude swing, up until the limits of zero flux and maximum flux linking the coil are reached, at which point the flux cannot increase any further, even if the amplitude keeps on increasing. In practice, even before any hard limits of flux are reached, the relationship between flux variations and amplitude variations stops being linear and flux increases progressively less than amplitude, so the electrical output starts falling.

A cut-off frequency between 1 – 3 Hz is common for the cartridge alone, below which the output would gradually fall.

But the cartridge is not alone! It is held on a tonearm. If we move the tonearm to the start of our favorite song on a record, it will stay there, absorbing the “DC” displacement. Likewise, if the spiral groove leads the tonearm across the record surface from the beginning to the end of the record, it is allowing a very slow displacement to be transferred directly to the tonearm, instead of bending the cartridge cantilever as far as it will go! Imagine if you would hold the tonearm still with your hand while the record is playing! The cantilever would just bend more and more, trying to follow the groove, up until it would skip or snap! But if we let it operate as intended, slow, large displacements, such as vertical warps and normal tracking along the record, are transferred to the tonearm pivots, allowing the cartridge to concentrate on reproducing the intentional groove modulation as audio.

This is due to the mass/compliance resonance of the tonearm/cartridge system, which effectively creates a mechanical crossover filter at the resonant frequency, typically between 8 – 12 Hz. This functions similarly to the crossover in your loudspeakers, but it is accomplished entirely by mechanical means. As the frequency is lowered, the entire cartridge and tonearm start to follow the displacement, while the cantilever remains stationary and the entire cartridge moves, below the “crossover” frequency. Under these conditions, there is no electrical output from the cartridge. Therefore, while the cartridge itself could, in theory, respond to frequencies much lower than the mechanical crossover, in practice the low-frequency response of the system is determined by the mass/compliance resonance frequency.

This is a good thing in disk record reproduction, as it filters out all the strange sounds that would otherwise creep in as a result of even the slightest warp. It does, however, adversely affect the low-frequency phase response, if not adequately dealt with by disk mastering engineers at the time of cutting the masters, and by designers of audio equipment (such as phono stages) to be used with turntables.

So, disk reproducers respond to the rate of change of displacement over time, above the mechanical crossover frequency of around 10 Hz. The rate of change of displacement over time, ds/dt, is the definition of velocity, which is why velocity is used to measure recorded levels on disk. This is the velocity of the vibrating stylus.

BL: To be picky, is that RMS velocity? Or average, or peak velocity?

JIA: The old NAB monophonic standard was an RMS lateral velocity of 5 cm/s at 1 kHz, which is equal to a peak lateral velocity of 7 cm/s at 1 kHz, which is equal to a peak velocity per stereophonic channel of 5 cm/s at 1 kHz, which is equal to an RMS velocity per channel of 3.54 cm/s at 1 kHz. But if we measure the velocity per channel in the actual geometric plane of the channel (45 degrees to the record surface), then it is 5 cm/s RMS or 7 cm/s peak per channel at 1 kHz.

Which is why it is essential to specify if the reference velocity figure given is peak or RMS, and lateral or per channel, along with the frequency. Looking through the dozens of different standards (and yes, there are dozens), these values (7 cm/s, 5 cm/s, 3.54 cm/s) all show up regularly in different contexts, without usually specifying what exactly is meant. This hints suspiciously in the direction of a generally poor understanding of the issue by many of the standards organizations and test record manufacturers.

BL: That would be a function of the amplitude and the frequency of the test signal engraved into the groove – right (which is, I assume, why both are stated)?

JIA: The frequency is important because of the RIAA curve. A quick, simplified explanation for readers who may not know: the RIAA curve is an equalization curve applied to vinyl records, which reduces the lows and boosts the highs on the record and does the reverse on playback equipment. The result is a flat frequency and phase response. The RIAA curve enables improved sound quality and longer cutting times.

The RIAA curve. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The RIAA curve. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

A record could be recorded at constant velocity, but the amplitude (groove excursion) would be too large at low frequencies and too small at high frequencies. Constant amplitude recording, on the other hand, implies that the velocity is no longer constant with frequency.

To better understand constant amplitude versus constant velocity, take a 12-inch record sleeve as a reference and slowly move your hand back and forth by 12 inches. Now do it faster, as fast as you can. It gets harder the faster you go.

Now allow your hand to reduce the amplitude to less than 12 inches, and you will notice that the faster you go, the lower the amplitude will tend to be. This is constant velocity, or as an over-simplification, constant effort. Constant amplitude requires that the amplitude remains constant (the full 12 inches) as your hand velocity increases (you’re moving it faster), which requires increasing effort, but keeps that motion clearly visible relative to the background, even from a distance. This results in an improved signal to noise ratio. Records are cut at constant velocity up to 50.05 Hz, constant amplitude from 50.05 Hz to 500.05 Hz, constant velocity once again from 500.05 Hz to 2122 Hz and constant amplitude yet again from 2122 Hz upwards, as defined by the RIAA curve.

This is unrelated to the linear velocity of the medium (the disk record) which is diameter-dependent, since the speed of rotation (rpm) is steady.

It is practically impossible to implement the RIAA pre-emphasis curve at the time of cutting, as it would imply infinite amplification to keep on increasing the drive to the cutter head at a rate of 6 dB/octave from 2122 Hz upwards, with no defined upper limit! The cutter head would certainly not survive this, even if the cutting amplifier system could do it. This is a topic worthy of a dedicated article, perhaps in a future issue.

BL: Move the stylus to a greater maximum amplitude displacement at a given frequency, or move it at a higher frequency at the same amplitude, or increase the amplitude displacement and the frequency, and the electrical amplitude of the phono cartridge will increase – right?

JIA: Electrical amplitude is proportional to velocity, ds/dt, in Faraday-principle cartridges. At a given frequency, increasing the amplitude of displacement, s, increases the velocity, since the variation in displacement values is made larger while the time (inverse of frequency) remains the same. Keeping the amplitude of displacement steady and increasing frequency reduces the time, while keeping the displacement values steady, which again increases the velocity. Increasing displacement values and reducing the time simultaneously increases the velocity to a much greater extent, as we are now changing both terms in the direction of increased velocity! For constant velocity, as the frequency goes up, the amplitude of displacement must go down. Since most phono cartridges generate an electrical output that is proportional to velocity, an increase in velocity will result in a proportional increase of the electrical output level.

BL: However, a reproduction transducer cannot output a DC signal [a signal of a steady non-zero value rather than alternating between positive and negative value]. If a microphone is presented with a constant air pressure, or if a tape head is presented with a constant magnetic field, or if a phono cartridge is presented with a constant physical displacement shift, the transducer is not capable of producing a DC electrical signal as an analog of what the “media” is doing. It will produce an impulse, and perhaps (probably) some “ringing,” [overshoot] but no DC, right? And this has nothing to do with AC vs. DC coupling of the signal path between the electrical components – even if all of the electrical components are DC coupled, these transducers cannot produce DC signals.[1]

JIA: Exactly. These transducers cannot produce a DC output. If they could, then microphones would produce a DC output proportional to atmospheric pressure, which would vary with altitude and weather phenomena. Phono cartridges would produce a DC output proportional to vertical tracking force, groove depth changes and groove pitch changes. Tape heads would produce a DC output as a result of the earth’s magnetic field, or any other permanent magnetic fields nearby. If the DC outputs of such devices would be accurately preserved all the way to the loudspeakers upon reproduction, then all we would achieve would be a displacement of the coil in proportion to parameters unrelated to sound.

This would cause an increase in distortion due to coil misalignment (since it would be displaced). Most listening rooms are not air-tight and practical loudspeaker drivers are not as efficient in pressurizing a room as they are in radiating sound waves.

Even if we would set up an airtight listening room with a loudspeaker system capable of DC pressurization of the room (at which point I suspect that both Underwriters Laboratories and your insurance company would take exception, in fear of your impending claim for the costs of your emergency medical treatment for self-inflicted divers’ disease), since the room would start with a given atmospheric pressure. If the microphone would have registered the exact same value of atmospheric pressure during the recording, the recorded DC would instruct the loudspeakers to pressurize the room even more, unless we also establish a complex feedback loop to sense the actual atmospheric pressure in the control room and ensure it matches the conditions under which the recording was made.

Apart from being unnecessarily complex, I wouldn’t want to know what would happen when trying to enjoy whale recordings under realistic conditions…something along the lines of what happened to the aliens in Mars Attacks upon hearing the yodeling of Slim Whitman! SPLAT!

Even worse, the orientation of the tape machine with respect to the earth’s magnetic field and the automatic groove depth/pitch control system found on many disk mastering lathes, along with record warps, would be translated into extreme pressurization of the listening room, which is far from a truthful recreation of the actual performance! [My head is ready to explode just contemplating this. – Ed.]

Fortunately, regardless of the transducer type and its ability to produce a DC output, typical microphone diaphragms are not mechanically sensitive to the static atmospheric pressure. Both sides of the diaphragm are open to the atmosphere (unlike the vacuum-operated power assisted braking servo mechanism in a passenger car), so a change in the static pressure would apply to both sides equally, preventing any displacement forces from being set up, even if we put the entire microphone in a pressure chamber.

Which leaves us with the great philosophical question of our century: how perfectly sealed should a sealed box loudspeaker really be?

_____

[1] AC coupling vs DC coupling: Electronic circuits are said to be DC-coupled when they can pass DC. AC-coupled circuits only respond to AC signals, blocking DC. If an AC signal exists superimposed on a DC bias, an AC-coupled circuit would still pass the AC, removing the DC offset. A DC-coupled circuit would pass both the DC and AC components.

Header image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Joost Dicker Hupkes.

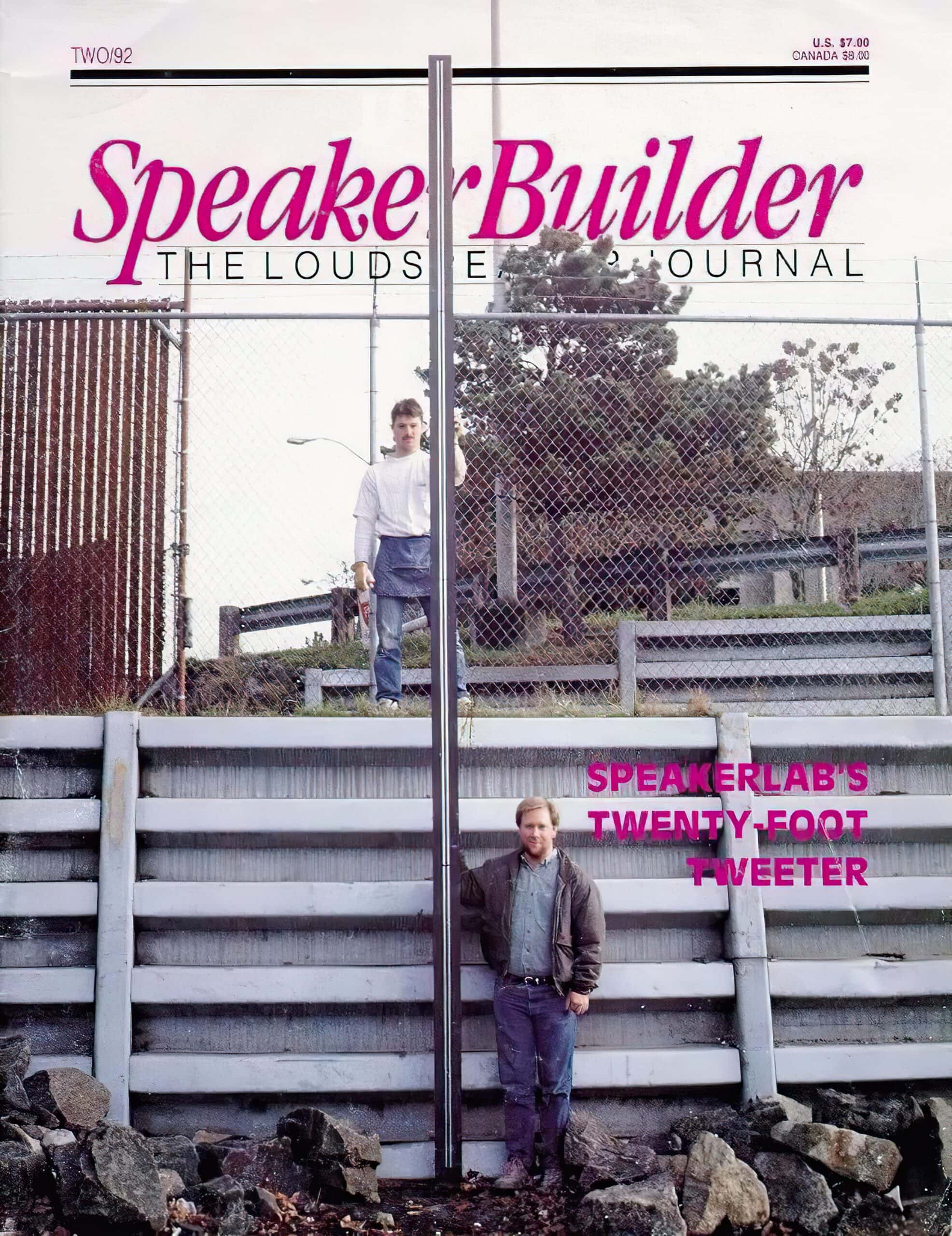

Attack of the 20-Foot Tweeter

Yes, this massive unwieldy thing was made to produce sound! It was made by a small, Seattle-based loudspeaker company, Speakerlab, for a research project on behalf of Boeing’s commercial airplane division. Boeing needed an acoustic line source – a speaker where the wave front of the sound propagates more in the shape of a cylinder rather than in the spherical shape of a traditional point source speaker (as the name suggests, a speaker that produces sound from a single point, or from components that are acoustically “small”).

Yes, this massive unwieldy thing was made to produce sound! It was made by a small, Seattle-based loudspeaker company, Speakerlab, for a research project on behalf of Boeing’s commercial airplane division. Boeing needed an acoustic line source – a speaker where the wave front of the sound propagates more in the shape of a cylinder rather than in the spherical shape of a traditional point source speaker (as the name suggests, a speaker that produces sound from a single point, or from components that are acoustically “small”).

Highly directional along its length, this kind of line source design can offer some unique acoustical properties and advantages, such as minimizing certain interactions with a room, increasing speech intelligibility, and halving the drop in sound pressure over a given distance. This giant tweeter was actually being used by Boeing for acoustic aerofoil (wing) research.

This “tweeter” was actually a wideband push-pull planar magnetic speaker that covered the human vocal range and beyond. It used a very thin membrane of plastic with conductive traces, with the traces laid on the membrane like pinstriping on a car. The membrane, which functioned as the speaker’s diaphragm, was placed between magnets of different polarities. When an electrical signal was fed to the diaphragm, it was alternately attracted and repelled by the magnets, causing the diaphragm to move back and forth and produce sound.

This wasn’t a new concept at the time – it was generally similar to some of the Infinity and Magnepan (Magneplanar) designs, but with some important construction differences to make it usable to over a wider frequency range, with higher output and with a line source-type of sound coverage.

Highly directional along its length, this kind of line source design can offer some unique acoustical properties and advantages, such as minimizing certain interactions with a room, increasing speech intelligibility, and halving the drop in sound pressure over a given distance. This giant tweeter was actually being used by Boeing for acoustic aerofoil (wing) research.

This “tweeter” was actually a wideband push-pull planar magnetic speaker that covered the human vocal range and beyond. It used a very thin membrane of plastic with conductive traces, with the traces laid on the membrane like pinstriping on a car. The membrane, which functioned as the speaker’s diaphragm, was placed between magnets of different polarities. When an electrical signal was fed to the diaphragm, it was alternately attracted and repelled by the magnets, causing the diaphragm to move back and forth and produce sound.

This wasn’t a new concept at the time – it was generally similar to some of the Infinity and Magnepan (Magneplanar) designs, but with some important construction differences to make it usable to over a wider frequency range, with higher output and with a line source-type of sound coverage.

Feel the quality! PS Audio's Paul McGowan and the Infinity IRS loudspeaker system.

Feel the quality! PS Audio's Paul McGowan and the Infinity IRS loudspeaker system. The Genesis II.5 loudspeaker.

The Genesis II.5 loudspeaker. Exploded diagram of a Bohlender Graebener NEO10 driver, a descendant of the 20-Foot Tweeter.

Exploded diagram of a Bohlender Graebener NEO10 driver, a descendant of the 20-Foot Tweeter.

How I Met Buck Dharma of Blue Öyster Cult

When I was a teenager I wanted to be a rock star. Every month, the magazines Creem and Circus came out and I devoured them, windows into that mythical rock and roll world I so much wanted to be a part of. In 1972 a review by Ed Ward in Creem raved about a new band called Blue Öyster Cult, and in particular, the talents of their lead guitarist, Donald “Buck Dharma” Roeser. The review encouraged me to get the band’s eponymously titled debut album.

By the second song, “I’m on the Lamb but I Ain’t No Sheep,” I was completely stunned. Electrified. The songs sounded like nothing I’d heard before, rocking hard but…different, with mysterious musical twists and turns and impenetrable yet evocative lyrics about motorcycle gangs, Canadian Mounties, silverfish imperatrix, cities on flame – all set to the beat of roaring guitars and Buck Dharma’s astounding lead playing. He was rocking but wasn’t playing the usual weedly-weedly rock guitar clichés of the day – it was a far more inventive and virtuosic style. I was hooked.

Blue Oyster Cult, 1977. Donald "Buck Dharma" Roeser is in white. Photo by Wikimedia Commons/Eric Meola, Columbia Records.

Blue Oyster Cult, 1977. Donald "Buck Dharma" Roeser is in white. Photo by Wikimedia Commons/Eric Meola, Columbia Records.

Some months later, an article in Long Island newspaper Newsday profiled the band, and noted that the band members lived on Long Island. Hmmm. I took out the Suffolk County phone book and looked for their names; Eric Bloom, Allen Lanier, Albert Bouchard, Joe Bouchard…Donald Roeser. There was the listing. And a phone number! Could that be the Donald Roeser? Not a common name…maybe I could just call him up and find out!

But I didn’t have the nerve. I was a shy kid and thought, you didn’t just call Rock Stars up. So…I wrote him a letter, on that lined paper that school kids use. I told him how much I liked his playing and the band’s music. I didn’t even know if it was getting to the right person.

A few months later Blue Öyster Cult was playing at the Schaefer Music Festival in Central Park, July 16, 1973. A friend and I went. I was bouncing off the walls with anticipation. I would get to see my favorite band live! They were fantastic. They looked great, lead singer/guitarist/man of mystery Eric Bloom in black wearing shades, Buck in a white suit playing a matching white Gibson SG guitar, a huge Cult symbol logo in back of the drums, walls of Marshall amps. And Buck’s playing was even better than on record. Wow!

At the end of the show I noticed a line of people outside a trailer by the stage. We thought, that must be where the band is. Let’s stand in the line…maybe we’ll get lucky and meet them. I had no experience in this sort of thing.

My expectations started sinking – as people got to the trailer entrance, an intimidating security guy would bark, “who are you?,” look at a list and then either let them in or not. Some practically pleaded – and were told by the guy to get lost. Not good odds.

I finally got to the door. “Who are you?” Mustering up all the chutzpah an awkward kid could, I replied, “My name is Frank Doris. I sent Donald Roeser a letter and I want to see if he got it. He might be expecting me.” To my amazement the guy sized me up and said, “Hold on. Let me go check.”

A minute or so later he came back and said, “go ahead,” waving my friend and I back into the trailer.

Oh my G-d.

We walked in and standing right there was Donald “Buck Dharma” Roeser, resplendent in the white suit with an attractive woman next to him.

Put this in perspective. What if one of you, at age 18, met Paul McCartney, or Miles Davis, or Jascha Heifetz, or whoever your personal idol is? That was what meeting Buck Dharma was like for me.

I was vibrating with excitement. Buck looked at me and said, “Hi! You’re Frank? Thanks for sending me that nice letter! This is my wife Sandy.”

He not only got the letter, he remembered who I was. Then Sandy also warmly welcomed me. Then the surroundings started to sink in. There was Joe Bouchard’s black, maple neck Precision Bass sitting on a stand. There were the other guitars. There were the stage outfits. There was the food and drink spread. There were the other band members! Beautiful women! Hangers on!

I was flipping out but Donald and Sandy immediately put me at ease. “Frank, Tim (my friend), let me introduce you. This is Eric, this is Joe, this is Allen, this is Albert…” We talked about their music, equipment, what it was like to play New York. We stayed for maybe 10 minutes – other people were waiting to get into the trailer. As I was about to leave, head spinning, Donald said, “We really appreciate you being fans of the band and coming to our show. Keep in touch.”

I had thought that Rock Stars would be arrogant, aloof, not wanting to even speak to mere mortals like myself, and here was my guitar hero going out of his way – to be a nice guy and thank me for coming!

Then Came the Last Days of May

We kept in touch. I would see the band whenever I could. Each time Donald and I got to know each other a little better. After high school I attended SUNY Albany and on May 24, 1975 BÖC played at the Saratoga Performing Arts Center. A bunch of us drove up to the show with a Blue Öyster Cult flag that my friend Ed’s mother had made for us flying from the antenna of an immense Dodge Polara. On the drive, fellow BÖC fans honked and waved at the sight of the flag.

A number of my friends had never seen the band before. By the end of the first song, “Stairway to the Stars,” they were blown away. After the next few songs, we were putty. Then the band took a pause and Donald got up to the mic. “We’d like to say hello to a few of our friends…X, Y, Z, and…Frank Doris!” My friends went nuts, screaming.

After the show we all got invited backstage and I got to re-live that whoa, we’re hanging with rock stars feeling all over again, this time through my buddies’ eyes. I remember asking Donald what his favorite part of the United States was. The Southwest, he replied, because of the beauty and uniqueness of the terrain.

We were among the last to leave the venue.

Don’t Turn Your Back

We graduated college in 1977. Around that time a friend and I went to a BÖC show at the Academy of Music or whatever it was called. (We nicknamed it the Academy of Drugs for the amount of pharmaceutical mayhem that took place there.)

At the end of the show we were almost in tears. We felt like it was the end of an era, now that we were about to enter the “real world.” And bands didn’t last, so maybe this was the last BÖC show we were ever going to see.

We had forgotten the band’s motto – “On Tour Forever.”

In fact, I did “lose” the band, and my connection with Donald, for a while. I lost touch with a lot of people during the 1980s, not the best period in my life. However, during this time I had been reading a column that Donald was writing for Guitar Shop. I contacted editor Pete Prown to see if he could put me back in touch, which Pete did. I e-mailed Donald and his reply was, “Hey Frank, it’s been a zillion years. How are you?” In 1997 we saw each other again at Tommyknockers in Farmingdale, Long Island. This time the guy at the door was expecting me. It was wonderful to see my friend again. It was as if the lost years never took place; you know how that feeling goes.

Still Burnin’

Since then we’ve gotten to know each other to the point where we exchange holiday cards. (Sorry I didn’t send any last year; I was overcome by events.) Among the highlights:

I invited Donald and Eric Bloom to a New York Stereophile show about 10 or 15 years ago. Donald’s into high-end audio and Eric wanted to check out big-screen home theaters. Donald said he was going to go incognito – and then he showed up wearing a badge that read, “CEO – Blue Öyster Cult!” Still, most show-goers didn’t recognize Donald, the man who wrote “(Don’t Fear) the Reaper” for crying out loud (we visited a bunch of rooms together) – but I wish I had a camera to get the double takes of those who did.

In July 2000 I had hernia surgery. A little thing like that wasn’t going to stop me from going to a BÖC show shortly after. By the end of the show (standing room only – what was I thinking) I was in a fair amount of pain. After the show Donald asked me if I was OK and offered to drive me home. I was touched. In fact, the guys in BÖC are generous with their fans, usually going out to meet them after the show.

My daughter grew up listening to music (no shocker there) and was a rock fan by the time she was a few years old. This isn’t an exaggeration. When she was five and found out I was going to see Blue Öyster Cult (at the IMAC Theater in Huntington, NY, May 4, 2002) she wanted to go. We got first-row tickets (and ear protection).

Since the first-row seats were just a few feet from the stage, the guys in the band saw her sitting there. During the last song of the set I held her up to get a better look – and the next thing we knew, she was up on the stage with Donald and the guys gathered around her, playing to her! The place went nuts. A once-in-a-lifetime moment.

In 2012 BÖC played at Mulcahy’s in Wantagh. By this point, going to a BÖC concert meant seeing a bunch of friends I’d become acquainted with after seeing so many shows (and seeing them is one of the most fun parts of going to a BÖC gig). A few weeks beforehand one my friend Alex had invited me to a birthday party for Donald she was throwing after the gig. She told me, “bring your guitar.”

Nassau Coliseum, Uniondale NY, August 2012. Photo by Tony DeStefano.

Nassau Coliseum, Uniondale NY, August 2012. Photo by Tony DeStefano.Does that mean what I think it means? Yes. I was going to get to play with Buck Dharma.

I practiced every day for three weeks.

I got to the party, acoustic guitar in hand. I’d be playing along with Donald and my friend Tony DeStefano, quite a player and singer. I was a little nervous but not a basket case. (Not to blow my own horn but I play on a professional level.) We played Beatles songs and other stuff. It sounded good! Really good. I had to pinch myself. We were actually doing this.

Donald hadn’t brought a guitar and someone handed him a Baby Taylor something like that. It wasn’t tuned to normal guitar pitch. “That’s OK; I’ll just play it.” And just took it and played it beautifully. I’d be stumbling in a situation like that. He was flying.

After the party Donald sent me an e-mail saying, “we sounded good. It was SMOOTH!”

OK, I’ve lived.

The last BÖC show I saw was at the Suffolk Theater in Riverhead on February 7, 2020. It was particularly outstanding, with the band blazing and pulling out a number of rarities (“Flaming Telepaths,” “In Thee,” “Workshop of the Telescopes”) for the hometown crowd. (The current lineup includes Bloom, Roeser, Richie Castellano on guitar/keyboards/vocals, Danny Miranda on bass/vocals and Jules Radino on drums.) After the gig the band and some friends went to Jerry’s, a nearby karaoke bar/restaurant.

Outside of the insiders, no one recognized Donald. “How does it feel to be ignored!” I joked to him. Shortly thereafter, the BÖC hit “Burning for You” came on the jukebox. The regular bar crowd still had no clue that the guy who did the song was right there. “That’s nothing,” Donald told me. “The last time we played here I went up and did karaoke to “Burning for You” and people still didn’t know it was me!”

As we were sitting at the table, we got a little philosophical, having known each other for so long. At one point Donald looked at me and said, “life is a journey.”

It sure is.

I’ll let him have the last word: “Getting older gives us both a different perspective on the whole journey. Life is good! It’s a great ride.”

Axiom Audio Celebrates its 40th Anniversary

Canadian loudspeaker and electronics manufacturer Axiom Audio is celebrating their 40th anniversary this year. Located in Dwight, Muskoka, Ontario, the company offers a range of wired and wireless speakers, systems and amplifiers. Double-blind listening and omnidirectional radiating patterns are key elements of Axiom’s design approach.

We asked Sound Advice columnist Don Lindich to interview founder and president Ian Colquhoun and R&D manager Andrew Welker and ask about Axiom’s past, present and future.

Don Lindich: This year Axiom Audio celebrated its 40th anniversary. That’s quite a milestone for any company. Ian, what can you tell us about Axiom’s beginnings?

Ian Colquhoun: I started Axiom right after leaving university. I had already been building speakers in my neighbor’s garage for a number of years starting in high school, so the passion was already there. Before Axiom was one year old, I had the good fortune to be introduced to Dr. Floyd Toole [an expert in the field of sound reproduction, acoustics and loudspeaker design – Ed.] who was conducting in-depth research into psychoacoustics as it related to speaker performance at the National Research Council (NRC) in Ottawa, Canada. This changed Axiom forever.

The garage where Ian Colquhoun built his first pair of loudspeakers.

The garage where Ian Colquhoun built his first pair of loudspeakers.At the core of the research was the double-blind listening test, which allowed measurements taken in an anechoic chamber to be correlated with listener preference in an unbiased test environment. The double-blind loudspeaker testing resulted in very consistent scores that related to the measurements across all listeners. It should be noted that if the same tests were conducted sighted, then the results tended to be skewed towards price, brand, and size; [and] not just [correlated to] the measurements like the double-blind test results.

The NRC laboratory was available to rent, so all Axiom product designs could be done in this state-of-the-art facility. But [we benefited from] far more than this, as I had access to all the research Floyd was doing, in real time, and got to participate in the double-blind listening tests he was doing and make samples that would aid in the research. This went on for 11 years until Floyd left the NRC to join Harman.

After this we went on to build our own laboratory at the Axiom factory in Canada. The laboratory included a full-sized anechoic chamber and a 100-foot bass measurement tower. The bass tower was built so that we could accurately calibrate our anechoic chamber below 80Hz. The height allows us to measure down to 10Hz with no reflections, so it is anechoic without being in a chamber. We also built a “torture chamber” for testing speaker power handling, double-blind listening test facilities, and a full electronics lab. We have continued our research at Axiom, based on what was learned from my 11 years at the NRC, to this day. DL: How would you describe your design philosophy and what principles do you adhere to when you develop new products? IC: At the core of the Axiom design philosophy is the double-blind listening test results. Products must score high in their respective categories or they get kicked back to the lab, or to the curb. This relentless focus on performance over appearance has resulted in some comments that our products do not necessarily look “exotic” enough, but our thinking is that there are lots of exotic looking products on the market to choose from. Axiom stands for performance. Because we make all our products to order at our factory in Canada, we can really customize the speakers for our customers. We do custom paint, custom stains, custom speaker depths when that is required for a particular installation, and even a custom amplifier that literally goes to 11 for Spinal Tap fans. It’s very satisfying to connect with our customers in this way – we become part of their home theater or stereo installation journey. All of Axiom’s drivers are built in-house at our factory in Canada. While we source most of the components offshore, all are designed and built to our specifications. A good example would be our current tweeter where the faceplate contouring and horn loading was designed, prototyped, and then die-cast tooled for us. The titanium dome shape, surround, and voice coil were all built to our detailed requirements. All of our woofers and midrange drivers use anodized aluminum cones for linear behavior within their operating regions, and most importantly for superior power handling. One area that we are very proud of is that our loudspeakers can take a beating without failure. Loudspeakers should not “break” just because you have a party and crank up the music! By assembling our drive units ourselves, we are able to control every aspect of production and subject each unit to state-of-the-art testing, ensuring each loudspeaker is a close match to our design reference. DL: Your omnidirectional speakers have received much acclaim from those who have heard them. Functionally they operate quite differently from the traditional definition of an “omnidirectional speaker” that simply radiates sound in all directions. They utilize forward- and rear-facing drivers. How did you come up with the concept and what kind of challenges did you face developing the speakers? [The company also makes conventional forward-radiating models as well as in-wall, in-ceiling and other types, and subwoofers – Ed.] IC: When Axiom first got into designing omnidirectional speakers, we had a huge leg up. Prior to joining Axiom, Andrew was the lead designer for [Canadian loudspeaker company] Mirage for 13 years. As a result, he already knew everything there was to know about omnidirectional design. In many ways [when we started doing omni speakers] I felt like that little kid again back when I first arrived at the NRC. This was exciting stuff. Andrew had always wanted to try using DSP [digital signal processing] to have finite control over the front and rear radiating sections of an omnidirectional speaker. This is how our original model LFR1100 was born. And now I am addicted to designing omnidirectional speakers. For an omnidirectional speaker the entire relationship between the on-axis, listening window, and sound power curves [the sound that a speaker produces at all angles] has to be rethought. Figuring this relationship out took endless months, years really, of measurements and double-blind listening tests. DL: In a relatively short period of time, Axiom has evolved from a traditional manufacturer of bookshelf speakers, tower speakers, home theater speakers and subwoofers to a full-line electronics manufacturer offering amplifiers, wireless speakers, soundbars, and single-piece sound systems like the AxiomAir Series. Without telling any secrets about future plans, do you see yourself expanding into additional product categories? IC: The move into electronics and writing DSP code began with our subwoofers. We were just not happy with what could be purchased in off-the-shelf subwoofer amplifiers. So about 20 years ago we decided that we would start designing and manufacturing these ourselves. Over the years, and exponentially since Andrew joined, we have developed a full line of electronics products. About seven years ago, we decided it would be a good plan to start developing wireless products that actually sounded good. This is when AxiomAir was born. We have lots of software-related plans right now for the AxiomAir wireless platform, and since the AxiomAir software is user-updatable, current owners can expect lots of cool updates in the months ahead. DL: Andrew, you have worked as an engineer for several well-known audio manufacturers. What attracted you to join the team at Axiom Audio? AW: I began my career at API (Audio Products International), the parent company of the Energy, Mirage, Sound Dynamics, and Athena loudspeaker brands in late 1997. I was fortunate to work for a great company with a talented group of people, including Ian Paisley, one of the best loudspeaker designers in the industry. The Klipsch loudspeaker group acquired API in 2006 and closed Canadian manufacturing operations soon afterwards, leaving only a small design and administration team. That ended in 2008 and I found myself out of work for the first time since high school. I considered options outside of audio, but I had the desire to keep pushing loudspeaker design and began discussions with a number of companies worldwide. I knew of Axiom and Ian Colquhoun, often driving by the factory when visiting Algonquin Park, and asked Doug Schneider (owner and editor of Soundstage.com) to put us in touch. The rest, as they say, is history. It was important to me that Axiom’s involvement with the NRC philosophically matched my own ideas about loudspeaker engineering, and it’s amazing that I’ve been able to work with the two Ian’s who learned alongside Dr. Floyd Toole. Axiom also manufactures their products in-house which is becoming a rarity in this industry. DL: You’ve been selling direct for a while. Can you comment on that? IC: We started selling direct in 2000. At first we weren’t sure anyone would buy speakers without listening to them first, but it turns out that people were already doing that in stores anyway – or listening to them in environments that weren’t at all like their home environments. We offered a 30-day in-home trial, generous return subsidies, and really active message board forums where you could ask other people for advice on what products to try and how to tweak your setup. We have over 15,000 members and thousands of threads that cover just about anything you can think of. That, coupled with staffing our telephone lines with experts from the industry really helped people get over the hump of not being comfortable buying online. The vibrant community has [even] met up in small groups all across the US and a couple of times at our factory in Dwight. DL: Ian and Andrew, answering independently, of all the products you have developed of which one are you the proudest? IC: I think the LFR1100 active omnidirectional floorstanding speaker. This was a complex design. The goal was to make the listening window and sound power curves match exactly. In a conventional front-firing speaker we know that a listening window and sound power that have similar linearity, except with a downward tilt to the sound power, results in a speaker that will win double-blind listening tests. With an omnidirectional speaker we had the ability to make these two curves identical, both in linearity and tilt. The result is a scary level of realism. I think we have achieved a totally new level of speaker performance.

AW: I’m going to cheat here and mention two products, the Mirage OMD-28 surround speaker system [an omnidirectional floorstanding speaker, not a surround-sound home theater setup – Ed.] and the Axiom LFR1100. The OMD-28 was my first complete from the ground-up loudspeaker. It was designed in 2007. I had a hand in every aspect of the product; from the cabinet, to mechanical design, to the drive units and their motor systems, cone and dome profiles, driver surrounds and crossover topology. It was a massive undertaking, and it took my patented Omnipolar technology to the limit.

Omnipolar technology consists of a midrange or mid-woofer on a specifically angled baffle with a reflective housing above it, also at an angle. At the top of that reflector housing is an up-firing tweeter with another angled reflector above it. The result is a loudspeaker with omnidirectional characteristics at mid and high frequencies, but with an energy bias that is skewed towards the front of the loudspeaker. This creates an omnidirectional soundstage with tighter image focus.

To this day I still have customers getting in touch to ask advice or talk about the OMD-28. The LFR1100 is the other design that I am most proud of because it fulfilled a desire that I had had for over a decade: to take the best performance aspects of a bipolar/omnidirectional design and combine that with the image focus and detail of an excellent forward-radiating design. It took the power of modern digital signal processing to achieve, but the LFR1100 is capable of performance that I never felt would be possible from an omnidirectional loudspeaker.

DL: Anything else to add?

IC: One of the greatest pleasures of having customers for 40 years is seeing their systems evolve over the years. We have a Wall of Fame on our website with pictures dating right back to the 1980s, and we still receive trade-ins from the 1980s and 1990s which we keep in our own Axiom museum. It’s such a gratifying part of being around so long. If anyone is visiting Algonquin Park post-pandemic, we’d love to meet you and give you a factory tour.

Axiom Audio

2885 Highway 60

Dwight, Ontario

Canada

P0A 1H0

1-888-352-9466

Songs of Praise From Unlikely Artists, Part One

Sex, drugs and rock and roll – the phrase is a catchall euphemism for the debauchery and revelry associated with the music industry. Tales of Dionysian excess, wild drunkenness, partying, and outrageousness are all tabloid fodder associated with rock musicians, as well as those in hip-hop, R&B, and country music. (Jazz wasn’t completely immune either.)

Yet throughout the history of American music, the influence of the Christian church has been apparent and well documented, with certain artists such as Rev. Al Green and Johnny Cash going unabashedly public with their faith in their public interviews, performances, and record releases. And gospel music, if not its message, would cross over to become part of the DNA of R&B, country, and rock and roll.

The 1950s had pioneering gospel-based rock from Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Little Richard (see WL Woodward’s piece this issue), Jerry Lee Lewis, and even Elvis Presley. All four would repeatedly have feet alternatively in the “sinner” or “saint” camps throughout their lives, having strong church roots that inspired their music but also pulled into conflict with the temptations of stardom.

In the late 1960s Glass Harp lead guitarist phenom Phil Keaggy, who counted both Jimi Hendrix and Mike Bloomfield as fans in awe of his prowess, converted to Christianity and spearheaded the “Jesus Rock” movement of the 1970s, along with Larry Norman, Marsha Stevens, and Keith Green among others. Keaggy is still active today. His groundbreaking work on both acoustic and electric guitar has wowed audiences and musicians worldwide from all walks of life, and he has continued to use his music and popularity to preach the Good News.

Christian rock sprang from these influential artists, giving the impetus for bands like Petra and Stryper to create international followings, albeit confined to their own niche. Among those musicians and bands who would lead to the eventual creation of Contemporary Christian Music (CCM), a genre with wider appeal, the only one to cross over successfully to mainstream audiences at the time was Amy Grant. Christian singer-songwriters have since become an integral part of the Nashville music scene and often collaborate with country, rock, and pop artists, producers and A&R executives. Some, including David Crowder, Matt Redman, and Chris Tomlin have built sufficiently large fan bases to fill sports arenas.

The boldly unashamed proclamation of Christian faith from Bono, The Edge and Larry Mullen of U2 gave inspiration and courage to many rock musicians of faith. U2’s success and willingness to advocate Christianity even at the risk of mainstream rejection spawned a whole genre of delay- and reverb-based rock music that has subsequently become a sonic style unto itself, categorized as Praise and Worship, or P&W. With Martin Smith and Delirious? and Hillsong United leading the way, other church-based music groups such as Jesus Culture, Elevation, Mosaic, Bethel, and Upper Room, to name a few examples, have rotating teams of musicians, similar to Mannheim Steamroller, that both perform weekly at their various church communities and tour in various cities.

The size of the P&W/gospel music industry has quietly grown exponentially. It currently outsells jazz, classical and New Age music in both physical unit sales as well as in downloads and in streaming. The fascinating story of this phenomenon is likely worthy of a separate article for another time.

While sonically less derivative than U2, a number of artists went on to varying degrees of commercial success with an appeal to both Christian and secular audiences alike. They took the stance of U2; i.e., “We’re individually Christian, but we’re not a Christian band.” Creed, Evanescence, Mutemath, P.O.D., DC Talk, and Switchfoot are all in that category.

For some artists, the effects of fame and popularity can test one’s faith and can lead to a lifelong struggle of walking the tightrope, as evidenced by Elvis Presley, Aretha Franklin or Jerry Lee Lewis (whose cousin is televangelist Jimmy Swaggart). In some cases, they made the choice to embrace the church, such as with Keaggy, Rev. Run (of Run-DMC), alt-rockers Jars of Clay, roots rockers Third Day, and Rev. Al Green. In other cases, the artists renounced and left the faith, most notably Katy Perry and Whitney Houston.

All these previously-cited artists either had some kind of prior connection with music from the church and started their careers as Christian or gospel artists, or made the decision to leave secular music careers to focus on music for God.

However, what about secular artists who have continued their careers, yet have performed and recorded Christian, faith based music – either overtly or covertly – on their albums?

If one were to cite recordings of Christian-faith songs from members of Megadeth, Alice Cooper, Soundgarden, Foreigner, Journey, Depeche Mode, the Byrds, or Hot Tuna, would that sound like a joke? If one were to include superstar solo artists like Eric Clapton, Blake Shelton, Prince, Van Morrison, Lenny Kravitz, Dolly Parton, or Marty Stuart, probably more than a few eyebrows would rise, if the notion didn’t generate outright peals of laughter.

What would be even more surprising is if these artists also wrote some of these songs, and are just part of an even larger group of musicians. Many of their names are recognizable from the past, like Steve Winwood, Kansas, and Rick Derringer, and others are currently in the public eye, like Hayley Williams of Paramore and Justin Bieber.

As we will see, truth can often be stranger than fiction, and the following stories prove it.

Megadeth

Multi-platinum selling thrash metal pioneers Megadeth are one of the most philosophically enigmatic and volte-face bands in history. Raised by dysfunctional, alcoholic parents, Dave Mustaine co-founded Metallica with James Hetfield and Lars Ulrich before being ousted for substance abuse and leadership clashes with Ulrich. He has admitted to dabbling with black magic and wrote a collection of anger driven songs with apocalyptic and Satanic references that propelled Megadeth to huge success. Bassist David Ellefson served as the Robin to Mustaine’s Batman, and Megadeth would have an ever-changing roster of different drummers and guitarists over the next two decades, with drugs often the cause of the revolving-door lineup.

In 2003, Mustaine converted to Christianity, and remains a Christian to this day. He was criticized for withdrawing from concerts where Megadeth was co-billed with other metal bands that espoused Satanism, the occult, and other negative spiritual credos. Not to be outdone, Ellefson began conducting Christian youth contemporary music worship services in 2007. Ellefson entered a Lutheran seminary in 2012 and became an ordained pastor some four years later.

While Mustaine and Ellefson have spoken candidly about their Christianity in numerous interviews, they have kept Megadeth’s lyrics primarily focused on politics, injustice, and apocalyptic themes of societal rebellion. However, “13” is one of the few songs in which Mustaine referenced his confrontation with the devil and his conversion.

Alice Cooper

For nearly a half century, Alice Cooper (Vincent Furnier) has been on the cutting edge of theatrical fantasy rock, bringing a Grand Guignol performance aspect to his concerts that presaged Kiss, Marilyn Manson, White Zombie and a host of other acts.

Musically, Alice Cooper has made landmark recordings, such as “I’m Eighteen,” “School’s Out” and the cynically prescient “Elected,” along with a host of gold and platinum albums and concerts that have often launched or highlighted the careers of top-notch guitarists such as Glen Buxton, Steve Hunter, Dick Wagner, Orianthi, Vinnie Moore, Reb Beach, Joe Satriani, John 5, and most recently, Nita Strauss.

When Megadeth was opening for Alice Cooper in 1986, Cooper took Dave Mustaine and the other musicians aside to warn them about their substance abuse, having entered AA himself. Mustaine still regards Cooper as a “Godfather”

The son of a Christian minister, Alice Cooper eventually went a full 360 degrees and returned to the church, publicly affirming his faith for the past 17 years. He is also very much the archetypal father of three, married-for-45 years family man when not on tour.

Cooper’s personal testimony is best represented by “Salvation,” from his Along Came a Spider (2008) album.

Cooper also collaborated with the late Chris Cornell of Soundgarden, himself a convert to Orthodox Christianity, on “Stolen Prayer” from The Last Temptation (1994). This allegorical retelling of the temptation of Christ received widespread critical acclaim and even inspired a three-part Marvel Comics miniseries written by Neil Gaiman (The Sandman). Chris Cornell recorded his own version of the song as well:

Foreigner:

As lead vocalist for Foreigner, Lou Gramm was the voice of FM radio rock throughout much of the 1980s with mega-hits like “Hot Blooded,” “I Want to Know What Love Is,” “Juke Box Hero,” “Cold as Ice” and others. His often-combustible relationship with co-founder Mick Jones led to Gramm’s initial departure from Foreigner in 1990. Prior to completing a Hazelden drug rehabilitation program, Gramm became a Christian and rejoined Foreigner in 1992. However, he was later diagnosed with a brain tumor in 1997. While the tumor was benign and the laser surgery to remove it was successful, the surgery damaged his pituitary gland and left Gramm with health and weight issues that affected his stamina and ability to tour, prompting his final departure from Foreigner in 2003.

In 1996, Gramm contributed vocals to the song, “We Need Jesus” by Christian rock band Petra. The experience may have planted the seeds for Lou Gramm’s solo vehicle, The Lou Gramm Band. A Christian rock outfit, their 2009 release contained songs of faith with Gramm’s instantly recognizable vocals in battle trim form and apparently fully recovered. “Redeemer” is a good example – it could easily be a Foreigner track, with its grinding guitars and mid-tempo drums.

Lou Gramm announced his retirement from touring in 2018. However, he has since continued working with friends, such as the band Asia and with producer/bandleader Alan Parsons in 2019.

Journey

How ironic is it that seeing singer Steve Perry with a Bible in hand is what prompted keyboardist Jonathan Cain, co-author of the omnipresent mega-hit “Don’t Stop Believing,” to find his way back to Christianity? Raised as a Catholic, Cain was traumatized by witnessing people trapped and dying in a fire at a young age, resulting in an estrangement from the church for most of his teenage and adult life. Cain credits Perry’s Bible wielding and especially his third wife, Pastor Paula White, with guiding him towards his current faith. He has released eight solo albums throughout his time with Journey, Bad English and The Babys.

Cain’s latest solo record, More Like Jesus, is an interesting hybrid of Journey-style pop rock and power ballads combined with the singalong corporate worship style of Hillsong United. While he occasionally plays backup guitar with Journey onstage, he takes on the lead guitar role here for the title song.

Depeche Mode

With songs like, “Personal Jesus,” “Precious,” “Mercy In You,” “Judas” and “My Joy” and album titles like Songs of Faith and Devotion, synth pop superstars Depeche Mode’s music reflects a longing and joy in finding Christ while maintaining a cynically observant perspective on organized religion. Chief songwriter Martin Gore and keyboardist Andrew Fletcher are both longtime Christians and the lyrics of Depeche Mode’s songs have sometimes begged the question of whether they’re the synth-pop spiritual equivalent to U2.

Not surprisingly, singer Dave Gahan, who has, astonishingly, survived clinically dying three times (heart attack, suicide attempt and drug overdose) but managed to be resuscitated on each occasion, has become the most devout Christian of the trio, becoming an Orthodox Christian in the 1990s.

In addition to his songs with Depeche Mode, Gahan’s solo work with the Soulsavers has allowed him to explore his blues and gospel music roots as well as express more details about his spiritual journey. “The Last Time,” in particular, from Angels & Ghosts (2015), lyrically touches on his 2009 battle with cancer and his walk with Jesus (who, in the song, lives in Los Angeles).

Part Two of this series will continue in Issue 113.

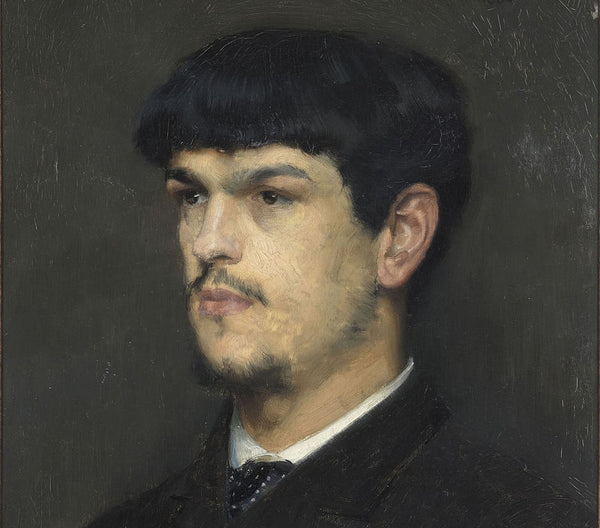

Header image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/JB Quentin, cropped to fit format.

A Quartet of Outstanding New Releases

I’ve been away for a few issues; and besides, there haven’t been an exceptional number of interesting new releases coming out during the pandemic — not too many artists in the studio. I hope you enjoy these as much as I have!

Steve Earle & the Dukes – Ghosts of West Virginia

Steve Earle definitely falls into a grey area for me; here in the Atlanta, Georgia outskirts, his music — if it got any airplay at all — was typically heard on rock radio for songs like “Copperhead Road” which had that kind of southern anthem theme going on. Jailed in the mid-nineties for heroin possession, he managed to get clean and has proceeded to generate a fairly regular output of albums since that are often all over the place stylistically — and not always critically or commercially successful. Earle lives and breathes country music, but he hasn’t always been deeply embraced by the country music industry.

Earle was definitely moved by the West Virginia mining tragedy of 2010, where 29 miners were killed in a horrific explosion at the Upper Big Branch mine, and he started writing songs that dealt with the tragedy. Jessica Branch and Erik Jensen wrote a play about the disaster, Coal Country, and after finding out about Earle’s great interest in the events, contacted him to provide the music for the play. It eventually ended up on off-Broadway to great acclaim, and this album, Ghosts of West Virginia, showcases the original music that Earle wrote for it. The songs dig deeply into the lives of those affected by the most deadly mining disaster in recent history, and share the tales of love, loss, and corporate greed surrounding the disaster. If not for the coronavirus pandemic, Coal Country would very likely still be playing to sold-out audiences. Most unfortunately, it will probably rarely (if ever) be seen by the very persons from the region whose lives are examined in the context of the tragedy.

At times more Americana than country, Ghosts of West Virginia doesn’t necessarily chronicle the events surrounding the explosion, but delves deeply into the lives and psyche of miners and their dangerous occupation, and the cast of characters intertwined with their existences. The song titles are virtually self-explanatory, with the likes of “Union, God and Country,” “Devil Put the Coal in the Ground,” “John Henry was a Steel Drivin’ Man,” “Time is Never on Our Side,” and “Black Lung” offering gripping and compelling examinations of Earle’s perspective on the human condition of the coal miners and their kin. Ghosts of West Virginia easily provides one of the most tightly focused narrative presentations of Steve Earle’s recent career.

The 24/96 stream via Qobuz was nothing short of excellent, and really helped highlight what a well-recorded album Ghosts is. This is Steve Earle at his very best, and it comes very highly recommended.

New West Records, CD/Vinyl (download/streaming from Qobuz, Tidal, Amazon, Google Play Music, Deezer, iTunes, Apple Music, Spotify, YouTube)

The 1975 – Notes on a Conditional Form

The 1975 is an English alternative, pop/rock progressive band that’s been performing for about 18 years now. The core members of the group met in high school, and the band presently consists of frontman and guitarist Matty Healy, guitarist Adam Hann, bassist Ross MacDonald; drummer and album producer George Daniel rounds out the quartet and also doubles on synths. The group’s previous three albums all hit the number one slot on the UK album charts, and they’ve done respectably here in the US as well, with their previous release, A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships reaching the number four position. Their music is incredibly difficult to categorize; some of it has an ethereal, almost ambient quality, while a lot of it is quite overtly poppish; Matty Healy says a lot of the group’s inspiration comes from country music. The opening track on Notes on a Conditional Form, “The 1975,” is an interesting case in point; on all their previous releases, there’s also been a track titled “The 1975” that’s been this kind of ever-evolving mission statement of sorts. On the newest release, it’s a nearly five-minute ambient treatise on climate change that features a lengthy spoken word segment by climate change activist Greta Thunberg. Not quite your typical fare for a chart-topping indie release, to say the least!

Notes on a Conditional Form was officially released on May 22, but somehow, the entire album ended up getting leaked and released online a couple of days earlier. Matty Healy has already had several intense social media exchanges with fans complaining about certain lyrical content in the new record. One of the record’s prominent tracks, “Roadkill,” doles out Healy’s response to an incident where a homophobic slur was tossed at him in an American airport. The fan in question declared, “There’s a line in the song that’s not f*cking cool. You can’t say that sh*t!” Healy’s response was, “First of all, you just stole my album and then came to me and complained about it?” He’s already joked on Twitter that he’s sending everyone who listened to the leaked album to 1975 Jail.

At nearly 75 minutes in length, Notes on a Conditional Form sprawls across subgenres, constantly flitting between ambient drones, folksy ballads, and twangly, twin-guitar power pop. Highlights for me are the absolute cojones of Healy to even think about including the opening Greta Thunberg rant track, the eerie calm of “Jesus Christ 2005 God Bless America,” the aforementioned power pop of “Roadkill” (despite the subject material), and “If You’re Too Shy (Let Me Know),” which has an eighties synth-pop kind of groove and sounds as though it could be the bands next hit single. The album closes with “Guys,” which is Healy’s tribute to his band members — they’ve known each other since high school, and literally spent over half of their lifetimes with each other.

All my listening was done with Qobuz’s 24/44.1 stream, and the sound was exceptionally good. While stylistically all over the place, Notes on a Conditional Form is an excellent album from a band that deserves to be on more people’s radar. Highly recommended.

Polydor/Interscope Records, CD/2 LPs (download/streaming from Amazon, Qobuz, Tidal, Google Play Music, Apple Music, YouTube, Spotify, Pandora, Deezer)

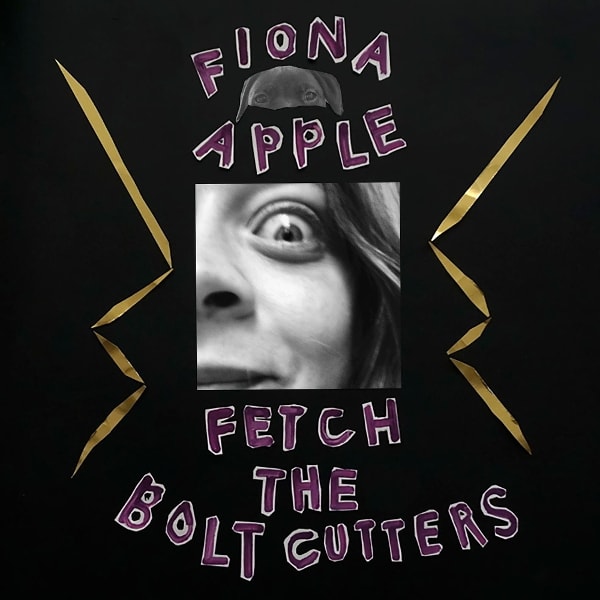

Fiona Apple – Fetch the Bolt Cutters

Fetch the Bolt Cutters, Fiona Apple’s first album in over eight years, has met with a surprisingly positive gush of critical acclaim since its release a few weeks ago. Shockingly, the Metacritic website (which monitors and compiles results of reviews and critiques from industry professionals) has thus far, based on 24 reviews, given it a 100-out-of-100 — its highest score, like, ever! And Apple’s near-rabid fan base has totally embraced her return to the spotlight from the captivating confines of Venice Beach, California. The album was recorded over a period of five years in her home studio, but sounds as though it could have been laid down over just the last couple of months; it’s about as raw and unpolished an album as you could possibly imagine. There’s very little here that follows anything approaching any kind of traditional pop music conventions — it’s mostly a cacophony of the mundane and the everyday. Apple and her words, and just about every household noise you could imagine: almost non-stop beating and banging of every sort, and at one point, there’s a chorus of about five dogs barking non stop in the background. The overall effect is surprisingly — intoxicating.

Most of the tracks are very sparsely instrumented, with occasional drums, bass, guitars, keyboards, synths, percussion, natural percussion — but never really all at the same time, just here and there. And I don’t think Fiona’s voice has ever sounded quite so self-assured as on this new release. The whole album sounds like it could have been recorded during the lockdown and pandemic. There’s plenty of self-deprecating humor, but Apple clearly has a firm grasp of who calls the shots in her current reality. On the title track — which has a lilting, kind of reggae vibe — Apple sings about childhood struggles. “The cool kids voted to get rid of me…I’m ashamed of what it did to me…they stole my fun…fetch the bolt cutters, I’ve been in here too long.” And as the song begins to wind down and segue into “Under the Table,” there’s the previously alluded to canine chorus of Mercy, Maddie, Leo, Little, and Alfie — Apple’s five dogs, barking away furiously.

And the song “Shameika” chronicles another schoolyard interaction with a girl named Shameika, who wasn’t particularly nice to Fiona, but nonetheless, “Shameika said I had potential.” Another outstanding track is “Heavy Balloon,” where Apple states that “People like us get so heavy and so lost sometimes…that the bottom is the only place that we can find…we get dragged down, down…the bottom begins to feel like the only safe place that you know.” Feels pretty much like what a lot of us are feeling during this time of the quarantine and everything, huh?

I found this album to be both introspective and entertaining. All my listening was via Qobuz’s 24/48 FLAC stream; the sound quality was absolutely superb. This is a really compelling listen, and it’s very highly recommended.

Epic Records, CD/LP (download/streaming from Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, YouTube, Spotify, Deezer, Google Play Music)

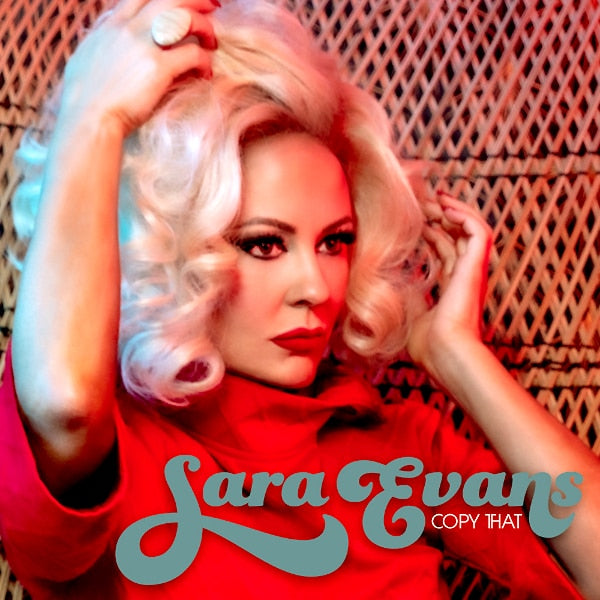

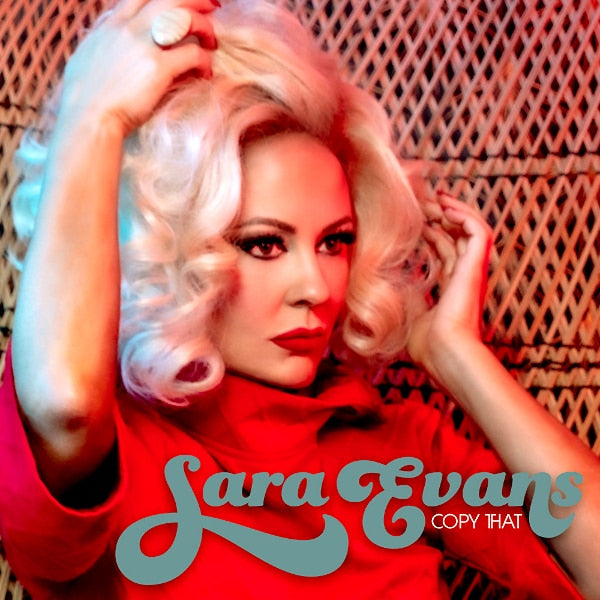

Sara Evans – Copy That

When country singer Sara Evans decided on an album of cover tunes for her tenth studio release, she said it was partially due to her reaction to the current state of country music. Which, she says, is a genre she feels like she no longer recognizes: “I just feel like aliens have come in and taken country music and done something with it.” I can totally relate — I’m not a huge fan of country music, but I’ve been around it my entire life, and much of what passes for country music nowadays is pretty out there in my book! Anyway, Evans had been rewatching episodes of Mad Men, the classic AMC series on the whole sixties Madison Avenue experience, and suddenly decided she wanted to sing cover tunes in a kind of Tammy Wynette channels Betty Draper persona. She got a couple of blond wigs and dressed the part for the album’s artwork — it’s pretty campy stuff, but also quite a fun look that’s very much in tune with the album’s dozen songs.

Evans’ prior recordings have always tended to hew much closer to the party line in terms of country credibility, but she’s also shown a knack for throwing in the occasional off-kilter cover on most of her albums. And this outstanding release follows in that mold, and if nothing else, proves that Sara Evans has a much greater range — both vocally and stylistically — than many might have given her credit for previously in a career of cranking out mostly boozy bangers and cryin’ in you beer ballads. Evans recruited producer Jarrad Kritzstein (Goo Goo Dolls and Weezer) and her three grown children, guitarist Avery and singers Olivia and Audrey, along with vocalist Philip Sweet (Little Big Town) and members of Old Crow Medicine Show. Only three of the songs here are technically country, including the Hank Williams’ classic “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” which is the first time in her career Sara Evans has ever covered a Hank Williams tune.

So, right out of the gate — I know, cover tunes? But shockingly, Sara Evans pretty easily pulls it off, opening with a pretty convincing version of the Bee Gees’ “If I Can’t Have You,” (as done by Yvonne Elliman), and she really shows her robust vocal range. And the album has surprisingly deep bass content; from the opening notes of track one, my dual subwoofer’s cones started moving and shaking to a degree rarely observed with even really demanding music! The best songs here are surprisingly the handful of country tunes, especially the Hank Williams cover with Old Crow Medicine Show, which has a really authentic fifties kind of vibe. And “She’s Got You,” the Hank Cochran classic where Evans channels Patsy Cline’s original to absolutely thrilling effect; son Avery offers some really choice guitar playing to complement Evans authentically plaintive vocal. Not everything works perfectly; “Whenever I Call You Friend” (Kenny Loggins) and “Hard To Say I’m Sorry” (Peter Cetera) are both a little cringe-worthy for me, although Evans does a credible job with each and Little Big Town’s Phillip Sweet delivers a pretty decent take on Kenny Loggins’ original vocal. At the very least, there’s a pretty great instrumental coda tacked onto the Peter Cetera tune that really lifts it out of the vocal maudlin of the original.

All said, this is a pretty entertaining, if not groundbreaking album, and definitely casts Sara Evans in a much more positive light for me personally — she can definitely sing! There’s not a ton of great stuff coming out in this time of the Corona pandemic, but this album proved good to help pass some of the quarantine time with upbeat takes on interesting songs, if nothing else. YMMV, but the 24/96 tracks on Qobuz sounded pretty outstanding to me! Recommended.

Born To Fly Records, CD/LP (download/streaming from Amazon, Qobuz, Tidal, YouTube, Google Play Music, Spotify, Pandora, Apple Music, Deezer)

Tales of an Audio Forum Administrator, Part Three

My last installment gave an in-depth look at what many forum moderators experience on a day-to-day basis. It isn’t the most glamorous job, but it’s ultimately rewarding enough that they stick with it.

What about the forum administrators? We may not seem to have much of a presence, but we are busy behind the scenes. Some administrators are not working on just one forum—they may have two, three, or even more that they oversee. In addition, many admins are volunteers, and/or have a full-time job in addition to administering the forum.

We have a lot of tasks that we cover. Some are daily or periodical, while others are longer-term maintenance or adjustments we need to make to the software or the server. Major upgrades, graphic redesigns and other major changes aren’t something that happen overnight. I’ll run you through a list of what a typical forum administrator might go through.

Daily or weekly tasks involve several things. A quick spot check of the public side of the forum lets us make certain everything is working as it should. This includes a glance at the statistics—how many visitors are online at any given time, and how many of those are members? This gives us a rough idea of the traffic we are seeing at varying points throughout the day.

A glance at the number of posts and threads indicates how much the forum content is growing. We also hit a few random but popular pages to see how the forum is responding, and make note if any condition of concern persists in case we need to address it.

We also have daily, weekly and monthly server maintenance. We have to clean out old log files, cache directories and other expendable items. We will open one of the resource monitoring tools which show the current processes (primarily memory, disk usage and CPU usage). The daily server logs need to be archived and removed from the site, as they can eat up a lot of space if left to accumulate. We also make certain that scheduled backups have taken place, and their files are stored off-site safely.

Longer-term maintenance includes monitoring appropriate resources, and digging into the server configuration to adjust anything possible. We may tweak our database configuration at least a couple of times per year. Our forum software is on a regular schedule of updates every two months, so those need to be applied, and any issues with the update resolved immediately.

Our current software uses a three-point versioning system. Using a version number of 2.1.5 as an example, the first point (“2” in 2.1.5) upgrade is a major upgrade where the entire backend of the forum is rewritten. (The backend is functional part of the forum, essentially the “engine” that processes the data and presents it in readable form to visitors.)

In most cases, these major upgrades break compatibility with older add-ons and themes a forum might use. (An add-on, or plug-in, will either add new features to the forum, or modify the appearance of a specific element in the forum. A theme, or style, is like a new “skin” that applies a new color and layout as an alternative to the default style provided by the forum software developer. Themes and just about all add-ons are created by third-party developers.) Thankfully, these first point upgrades only happen only once every several years.

Second point upgrades (“1” in our example) are primarily feature upgrades and major bug or operational fixes. These usually occur every 12 – 18 months. Third point updates (“5”) are for security patches and bug fixes, which are released every two months, or sooner if severe security flaws are found. These generally create few if any issues.

The second-point feature upgrades sometimes cause a little work for an administrator. Some add-ons will break, and some themes will need to be fixed, so we usually wait until our major add-ons and themes are updated by third-party developers before we upgrade the forum. Many of us run a private testing forum on which to do our future development, and we try to test everything thoroughly before deploying it. Luckily, most feature upgrades are not all that troublesome.

The most work an administrator will do is when there is a major first-point upgrade in the wings. Since it is almost like starting fresh, the default forum theme needs to be tweaked, and third-party themes need to be customized. Add-ons need to be tested thoroughly but even more importantly, we need to wait for major add-ons to be rewritten for the new version, and that sometimes takes several months. We like to roll out an upgrade with all the same features in place if possible, as we want to do nothing but improve a visitor’s experience on the forum. These types of upgrades require advance planning, and some of us will take the opportunity to give the site’s graphics an overhaul (a refreshed logo, new color and style page layout changes, etc.). Nothing we do in planning an upgrade is done off-the-cuff—it can take months of planning, preparation and testing before launching the new site.

What is worse than a launching a first-point upgrade? Converting from one forum platform to another. Without getting into a lot of technical detail, achieving feature parity is often not possible—we can guarantee most, but not all, features will carry over to the converted forum. There are many technical hurdles as well to make certain we transfer as much of the data over as we possibly can. Fortunately, the forum developer offers import scripts that handle the bulk of the data importing, and we run a few trial imports first, to make sure the process works as intended. This is in addition to the work we perform for first-point upgrades but luckily, these conversions are seldom needed.

Upgrades and conversions lead to even more work—educating the members on how the new features work. I tend to put together tutorials for members and post them in an appropriate place, and add some of these to a series of help and FAQ pages for future reference. There is also a lot of troubleshooting that inevitably happens right after the upgrade is implemented. As any developer will tell you, once you unleash your creation to the public, they find every way imaginable to break it!