Loading...

Issue 109

Balancing Act

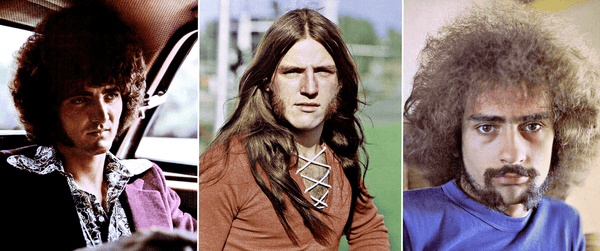

Grand Funk Railroad: Chuggin' Along

All over America in the late 1960s, teens were forming bands. The one started by Flint, Michigan high school friends Mark Farner (guitar/vocals), Don Brewer (drums/vocals), and Mel Schacher (bass) – Grand Funk Railroad, a pun on the Grand Trunk Western Railroad line in Michigan – managed what most other bands only dreamed of: They made it big, and they did it fast.

Within a year of forming in 1969, they were such a hit at the Atlanta International Pop Festival that Capitol Records signed them. The marketing smarts of their manager, Terry Knight, who’d been the leader of Brewer’s previous band, helped the trio make the right industry moves.

Apparently, the world was primed for an American version of the hard-rock, bluesy sound of bands like Cream. Their first album, On Time (1969), sold more than a million copies. “Time Machine” and “Heartbreaker” were the album’s singles.

Ending side A on the vinyl, “T.N.U.C.” is a nearly nine-minute track that’s believed to be about Farner catching his girlfriend cheating. (Read the title backwards.) The song settles quickly into an engaging groove thanks to Schacher’s repeating bass patterns. The complex, tight drumming of Brewer is always just this side of frantic but never over the line. Check out his solo at 2:45.

1969 was quite a year for this new band. They pushed out a second album, Grand Funk, in December, which was soon certified gold. The singles were “Mr. Limousine Driver” and “Heartbreaker.” But probably the favorite track among fans – particularly for its live version – is the cover of “Inside Looking Out,” originally recorded by The Animals.

My personal recommendation on this album is “Winter and My Soul.” The tinny production on Farner’s mournful blues guitar opening (produced by Terry Knight) calls up the image of some old fellow playing slide guitar on a porch in Mississippi. The vocals, on the other hand, are strongly reminiscent of the wandering lyric rhythms of Cream.

The next album, Closer to Home (1970), brought their total of gold albums to three in a 12-month period. While “I’m Your Captain (Closer to Home)” is the big single from this record, its B-side, “Aimless Lady,” is worthy of attention.

The rhythm section is a rumbling thrill, gritty and smart. The vocal harmonies during the chorus layer an eerie screech over Farner’s wailing melody. This is some high-octane stuff.

Survival (1971) is notable both for its silly caveman cover art and for its long tracks, even longer than usual for this band. Side B had only three tracks. The singles were each well over four minutes, with one of them, a cover of the Rolling Stones’ “Gimme Shelter,” clocking in at six and a half.

Side A opens with the anti-Vietnam War song “Country Road,” angry and heavy, emphasizing the contrast between the bass register – like soldiers’ plodding boots – and Farner’s high voice. Producer Knight had heard that Ringo Starr put tea towels over his drums, so he insisted Brewer do the same. Brewer never was happy with the sound.

Still going strong, GFR made industry headlines by beating the Beatles’ attendance and sell-out time at Shea stadium during their own show there in 1971. To honor that achievement, the stadium is pictured on the cover of their other 1971 album, E Pluribus Funk. But, while they were selling plenty of albums and concert tickets, they weren’t producing smash singles.

And there was another problem. Terry Knight, who was still their manager, seemed to be mishandling funds. The band felt they had no choice but to fire him in 1972. GFR took over their own production for the next record, Phoenix. Its single, “Rock & Roll Soul,” made a better showing than the previous few releases had, peaking at No. 29.

“So You Won’t Have to Die” is an interesting track, a combination of Christian rock and social commentary, taking on the issue of over-population. The extreme tempo change and introduction of the organ about two minutes in edges this song into prog rock territory.

It’s a safe bet that, if you don’t know any other GFR songs, you do know “We’re an American Band,” the huge hit single off the 1973 album of the same name. Despite endless legal entanglements with Knight, the band succeeded in rising even higher in the rock star echelon with this album, helped by the production talents of Todd Rundgren.

“Loneliest Rider” is a hard-driving rock-out with a social message. To bolster the theme of Native American civil rights, the verse’s melody uses a whole-tone scale and simple, unsyncopated rhythm to imitate Native music. Today it comes across as an unfortunate stereotype, not bothering with any real ethnomusicology, but in the 1970s other well-meaning bands, earnest about their concern for American Native tribes, used this trope (see Queen’s White Man for a much more cringeworthy example).

GFR released two albums in 1974: Shinin’ On and All the Girls in the World Beware!!! From the latter, the band had a bestseller with their cover of John Ellison’s “Some Kind of Wonderful,” showing their more sensitive soul-music side. The memorable album cover features the bandmembers’ faces superimposed onto bodybuilders’ physiques.

Another nice track from that album is “Runnin’,” by Brewer and keyboardist Craig Frost. Given the party-like approach to the drum kit, it’s hardly surprising that Brewer had control of this song. It also demonstrates differences between Brewer/Frost and Farner’s songwriting: Brewer-Frost used shorter lyric phrases and harmonic motion, more in keeping with standard R&B.

The title song from Born to Die (1976) is an homage to one of Farner’s cousins, who had recently died. Overall, the themes on this record are more serious than on the previous couple of albums.

Another example of this newfound darkness is the Brewer/Frost “Dues.” Its lyric, which starts with the line “I think I’m heading for a terrible accident,” betray desperation and rage over society’s shortfalls, whereas earlier songs that criticize society seem merely puzzled and frustrated.

They put out another album in 1976 called Good Singin’, Good Playin’. Although it was produced by Frank Zappa, it sold poorly. The band took a break after this, coming back together five years later for Grand Funk Lives (1981). But the lineup was significantly changed. Schacher and Frost did not return to the studio, replaced by Dennis Bellinger and Lance Duncan Ong, respectively. You’ll also notice that “Railroad” has been dropped from the band name.

Nothing on Grand Funk Lives broke the top 100. “Wait for Me,” which closes the album, demonstrates that what used to be an edgy and experimental hard rock band has gone full-out ’80s arena rock. Wave your cigarette lighters to the beat, folks.

After this, they made only one more studio album, What’s Funk?, in 1983. However, the band continues touring to this day. The current line-up includes former Kiss guitarist Bruce Kulick and 38 Special’s Max Carl on vocals (Farner left to focus on Christian music), along with Brewer, Schacher and keyboardist Tim Cashion. The Railroad keeps chuggin’ along.

Header photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Premier Talent Associates.

Obsessed with Stereo, Redux

I think about my system too much. I mean, really too much.

As I’ve written many times, it was stable for more than 20 years. That’s a really long while in anybody’s reckoning. In those years, I don’t remember thinking about it so much. Of course, I also played on a bunch of records and was raising my daughter, and having a good stable system that I didn’t have to think about was a real blessing. I feel like I’ve only now just cracked the beginning of getting it to another version of stability.

I’m listening to David Sedaris talking about obsessive compulsive disorder. To hear him talk about it, no, this is not that bad (though my daughter might insist otherwise). I may not like trash by the side of the road, but I don’t have a compulsion to pick it all up. And certainly, most of my musician pals thinks I’m either crazy, or wealthy, or…well, they don’t know what. I guess the missing word is obsessed. I mean, who has a studio monitor system in their living room? (I feel like Rowan Atkinson’s character in Love, Actually: “But this is so much more than a monitor system…”)

When I wake up, I flick on the preamp (which after 20 seconds turns on the amps) so that it’s fully cooked by the time I put music on. I usually start with something relatively quiet. Just the fact that it’s become routine says something about my days – aside from never-ending yard and pool work and caring for ten rabbits (count ‘em! Ten!), I mostly try to figure out how to move this damn television project forward. So I have the mental space for this obsession.

It’s not that I think about my system to the exclusion of other things. But when I’m home, the fact that I’m aware of it needing something plagues me. Wondering if it would have similarly needled me for the aforementioned twenty years is pointless – but I don’t think so. For the last month, I’ve had a BHK Signature preamp in the system (I put in a pair of 7dj8 tubes a couple days ago), which went a long way to resolving what bothered me about what I was hearing. I feel like the quality of the system is back where it was when I had the EAR G88 preamp in it, more or less. (As I’ve written, if I had to point to one thing, it turns out, surprisingly, to have been the low end). OK, so…what? What is this obsession about? Maybe my daughter is more right than I’ll admit.

It’s a mystery to me why she doesn’t care. Ten years ago when we were at Brooks Berdan’s shop, I made some crack about her not wanting anything of mine, and she said the only thing she wanted was my Moog synth (how things change). She listens to music on her computer, or via ear buds, and would be perfectly happy to hear the teevee coming out of its completely inadequate speakers if that moved my system out of our living room.

So now it’s the amps that are the concern: the Brown Electronic Labs BEL 1001s. There is nothing wrong with the amps. In fact, they’re extraordinary. They were when I got them, 26 years ago, enough to convince me to give up VTL 500s. Since then, they’ve been through everything but the last bit of upgrade (one of the benefits of being a writer for The Absolute Sound, which made a point, from 1992 on, of championing Richard Brown’s work with BEL before he died). I put on a spacious, beautifully-imaged recording and it’s all there, well beyond the edges of the speakers, everything in proper proportion when the playback level is correctly set.

So I think it’s the story I tell myself, about having a system that’s all made by my friends, or the story we tell ourselves: a need to chase the current state-of-the-art. I think I won’t really be happy until I replace the amps. But…

Maybe it’s just some damned obsessive acquisitiveness.

Maybe it’ll take just one more fix….

In Memoriam: Art Dudley

The audio industry lost one of its greatest with the passing of Stereophile Deputy Editor Art Dudley on April 14, 2020 from metastatic cancer. I’m having a tough time writing this because I got to know him well over the decades and because he was one of the finest people I’ve ever met.

Art was an exceptional writer. His reviews were thoughtful, insightful, laced with humor and attitude and could have been written by no one else. (He once said that too many audio reviews read like they were generated by a software program; just insert the model number, specs and price and presto, instant audio review. You could never accuse Art of that.)

He was opinionated. He thought New York State wines were lousy, and liked low-watt tube amps, vintage Altec loudspeakers, and rebuilding old Garrard idler-wheel turntables, among many other things. He did not suffer fools all that gladly, but was also self-deprecating, often hilariously so. In the March 2020 Stereophile he wrote: “…domestic audio has attracted an almost incalculable number of iconoclasts, heretics, mavericks, nonconformists, lone wolves, enfants terrible, and hidebound kooks. Because the above are among my favorite people, I don’t have much of a problem with that state of affairs.”

He prized audio components that were beautifully crafted and could convey the life, drive and humanity of the music, and was unimpressed by those that couldn’t. In the middle of one review a few years ago, where he was exasperated with the component’s performance, he simply concluded a paragraph with, “Jesus wept.”

Art was an accomplished guitar player, as I found out when I got to play with him at a party at fellow Stereophile writer and friend Bob Reina’s summer house in Mattituck, NY. (The late Reina has never gotten the tribute he deserves and that will be remedied in a future issue.) Like anything Art did, he would talk about guitars, bluegrass and other loves with enthusiasm and the often obsessive detail so characteristic of people who are really into it. He wrote wonderful pieces for Fretboard Journal.

Gigging with the Mountebank Brothers. Photo courtesy of Tripp Swart/Facebook.

Gigging with the Mountebank Brothers. Photo courtesy of Tripp Swart/Facebook.

Art Dudley started in audio in 1985 as managing editor of The Absolute Sound, where I first had contact with him as I was trying to worm my way onto the staff. I sent him “audition” pieces and once, a photograph of two vintage 1965 and 1967 Fender Stratocasters I had owned. That got a response from him! We got to know each other and I was struck by his honesty, straightforwardness and intelligence. After Art quit TAS to start the excellent audio magazine Listener, when I asked him why he left, he said with typical candor, “because I got tired of the bullsh*t.” (That was around the time I started at TAS. But Art wasn’t about to sugar-coat anything for me.)

Art eventually sold Listener to Belvoir Publications, who sadly closed the magazine’s doors in 2002. He also wrote for Hi-Fi Heretic and Sounds Like… (ah, memories…) and in 2003, began writing for Stereophile, becoming one of its most beloved contributors and eventually, its Deputy Editor.

I ran into him dozens of times at shows and industry events. He was always well dressed, always wearing a sports jacket even if said jacket was a year or ten out of style. (But that’s kind of a thing in the industry anyway. Victor Goldstein and some others excepted!) Since Art was something of a celebrity in said industry he would always be accosted by people at shows, many times by audiophiles asking for advice. Art would always spend time with them and be kind and gracious, even if he was clearly late for an appointment or if the person he was talking to was obnoxious. I know he loathed being asked things like, “what’s the best speaker for under $1,000?” But he always answered with a smile, even though I knew that for him it was the equivalent of plantar fasciitis.

A few other examples of the kind of guy he was: when I once told him I had friends in upstate New York and visited them regularly, he told me he lived on the way and that I’d be welcome to stop by his house any time and even jam with his band if they were playing a gig. Every time I’d run into him at a show I’d say I’d come visit him, never did, and it got to the point where, on one of the last times that I saw him I sheepishly greeted him with, “I know, I know, I’m going to stop saying I’m going to come visit because I never do it.” He smiled and said something like, “no problem; I know we’re all busy but any time you want to visit our door is open.”

About 20 years ago I was looking for a vintage-correct pickguard for my 1969 Telecaster (the original having been lost to the ravages of rock and roll). I responded to an ad in Vintage Guitar magazine. The guy who answered the phone was feeling me out. When we got to the point where we were discussing payment terms he said, “you sound like a decent and trustworthy guy; just send me a check. Where do you live?” When I told him on Long Island, he said, “wait a minute…your voice sounds familiar…Frank?” Then it hit me. “Art? Oh man, how have you been? It’s been years!” We then spent the next few minutes apologizing, embarrassed and laughing that that neither one of us realized who the other was at first. We both knew that a 1969 Telecaster pickguard should have a mother-of-pearl-looking backing – but didn’t recognize each other’s voices.

We loved to talk about music, especially since we shared many contrarian opinions about what was good and bad. (I wish I had tapes of our conversations where we would skewer some of the typical audiophile show demo tracks.) Art knew I was a serious Blue Öyster Cult fan and when I ran into him a couple of New York shows ago, he brought up the fact that the band’s Secret Treaties album was his favorite. We then proceeded to have a song-by-song rave session about the album right in the middle of the hallway, to the bemusement of those around us and ignoring everything else we were supposed to be doing. Art’s favorite song on the album was “ME 262.” (Yep, the same guy who loved Mahler and Monroe dug the Öyster Boys’ hard rock.) A couple of years later he told me he finally got to see BÖC live, that they had played it and that he was thrilled. From now on I’ll never be able to play the song without thinking of you, Art.

I think Art would appreciate this last anecdote.

On April 14 I got my copy of Stereophile in the mail. As usual, I immediately opened to Art’s column. (No offense, Michael, Kal, Jason and the rest of you!) I read it, laughed yet again about something he wrote, and then to finish my lunch break looked at Facebook. The first thing I saw was Art’s obituary. Right after I finished reading his words and smiling at them, I saw the news about his passing.

I’d like to think that he was up there somewhere smiling at the bittersweet irony.

We will miss you Art. More than I can express here.

How to Lie with Measurements

In view of my recent series on linearity and other technical topics before that, the time is perhaps now ripe to discuss audio measurements.

I will focus on what is probably familiar to most audiophiles and hopefully even more familiar to equipment designers: frequency response plots!

A few days ago, I was designing some audio electronics in the deepest corner of my cavely lab and was testing the performance of the prototype with a rather expensive transformer, intended for audiophile use. Something wasn’t right so I ended up testing a bunch of transformers I had lying around the bench, measuring the transformers on their own (rather than installed in the product).

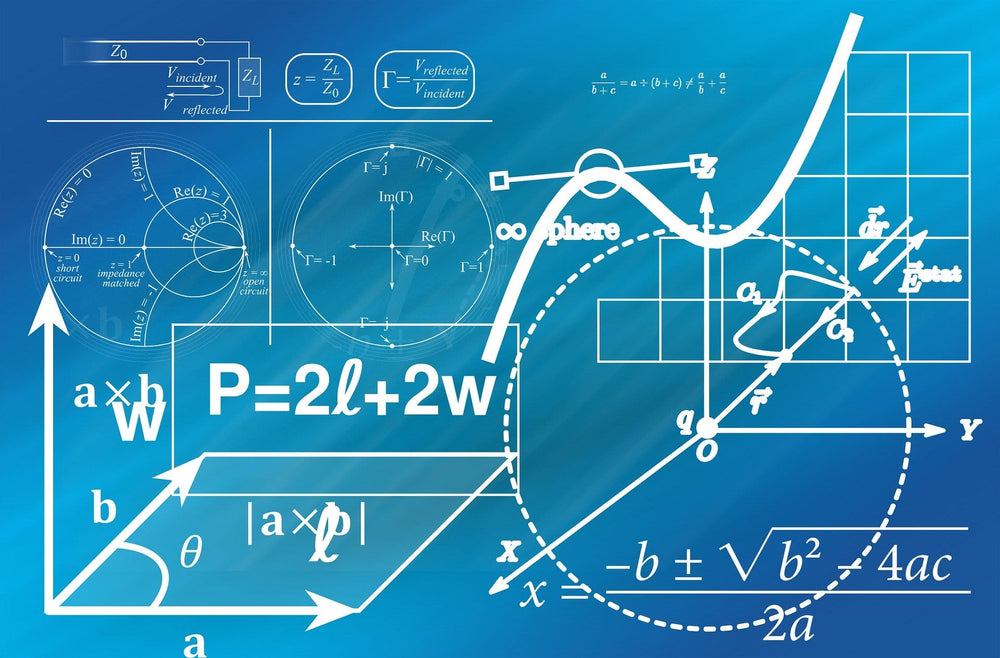

The results for this particular and expensive unit were shockingly bad, but the severity of what looks like “a bit of a ripple around 20 kHz” would be better appreciated if we change the display from 10 dB per vertical division to 1 dB/div, all other settings maintained as before.

This is a 20 Hz – 43 kHz plot and the 1 dB/div resolution reveals a dramatic resonance, caused by unintentional aspects within the transformer: leakage inductance and winding capacitances. An unfortunate combination of such parameters renders this massively built transformer practically useless for serious audio use.

The difference in the display between the 10 dB/div and 1 dB/div settings demonstrates the first thing to look out for when trying to correlate measurements with performance: what are we actually looking at? Is a tiny blip in the middle of the plot really as tiny as it looks, or are the scale and smoothing settings “artistically selected” for a more flattering display?

This leads to a second question: all transformers contain the aforementioned unintentional components and therefore, they must all exhibit resonance at some frequency.

But how is the above plot, of a different, better transformer, possible?

Where is the resonance? As mentioned earlier, these plots are all 20 Hz – 43 kHz in a logarithmic scale along the horizontal axis. Any anomalies occurring below 20 Hz and above 43 kHz are not going to be displayed on this plot! We could pretend they are not there, since anything outside this frequency range is outside the traditional concept of the “audible range” anyway. But as mentioned in Issue #107, frequency response errors outside the 20 Hz to 20 kHz range could cause phase response errors within this range!

In practice, excellent audio transformers are designed and constructed in ways that push these resonances so high up in frequency, and compensate for them to derive a gentle roll-off rather than out-of-control peaks and dips, as to be of little to no practical consequence in audio applications. Such transformers can exhibit a smooth frequency and phase response over an even wider range than 20 Hz – 20 kHz.

That same transformer maintains a respectable plot even at 1 dB/div resolution, being 0.5 dB down at 20 Hz, correctly terminated… wait… did I just say “terminated”…?

Several years ago I found this cheap single-ended output transformer in a vacuum tube table radio made behind the Iron Curtain. Nothing to expect outstanding performance from. So, here’s how to lie with measurements:

Isn’t this one of the most outstanding single-ended transformers ever?

Begs to be used with the finest example of a 300B output tube…or not?

This was at 10 dB/div, terminated in a 1 megohm resistor, which is to say, nowhere near its real-life operating conditions.

This is the same but 1 dB/div. Already a bit less flattering. In actual use, this output transformer would be expected to drive a loudspeaker. So we should try terminating it in a more realistic loudspeaker impedance value, say 8 ohm, 1dB/div:

Oops! How about 4 ohm, 1 dB/div?

We’re 5 dB down at 20 kHz, and 3.5 dB down with an 8 ohm load. In an actual circuit, driving an actual loudspeaker, this is likely to be slightly worse, but given what this came from, it is certainly better than expected.

A 50 Hz to 8 kHz bandwidth was a typical design aim for AM table radios in the late 1940s. But we would most likely be able to sell it for 10 times as much if we conveniently set the analyzer for 10 dB/div, still keeping the 4 ohm termination:

Still 5 dB down at 20 kHz, but looks better, doesn’t it?

But what is so special about audio transformers? Can’t we just use a much cheaper power transformer as an output transformer?

Audio transformers need to operate over a very wide frequency and dynamic range. This calls for special core materials, special winding techniques, special insulation materials, tight parameter control and attention to detail.

There are certain power applications which may have similar requirements, but audio is on a whole different level. As an example, this is the 1 dB/div plot of a special industrial transformer I designed a while ago:

Not really audio-grade, but maybe acceptable in a guitar amplifier, though the cost might put you off. It does what it was designed for very well, and it certainly isn’t audio.

As for the average off-the-shelf, mass-produced power transformer? Judge for yourself (1 dB/div, 8 Ohm termination)!

Ryuichi Sakamoto: A Musical Career Overview, Part Two

Part One focused on Ryuichi Sakamoto’s work in the groundbreaking Yellow Magic Orchestra. In Part Two I look at his solo work, film scores, collaborations into different types of ethnic music, and his activism.

Solo Artist and World Music Collaborator

Even prior to the Yellow Magic Orchestra, Ryuichi Sakamoto had pursued numerous musical directions as a solo artist. While his blend of electronic experimentation, classical training and love of orchestral textures has made his solo music distinctly different from the more song oriented styles of Hosono and Takahashi, Sakamoto’s interests in music from other cultures and eras has allowed for fresh approaches and arrangements towards both new and previously recorded material from his catalog.

Sakamoto has continued to explore different collaborations in experimenting with a host of music genres, such as: bossa nova, Renaissance music (with period-accurate instruments), musique concrète, and has also appeared with a number of artists, such as David Sylvian, Bill Nelson, David Byrne, Iggy Pop, Thomas Dolby, Arto Lindsay, Robbie Robertson, Brian Wilson, and Alva Noto, among others. He has over 250 releases as a solo artist, composer, or collaborator. As this is an exhaustive body of work, some of the more significant recordings are worth mentioning:

After his Thousand Knives album, he continued issuing solo records filled with electronic experiments, such as his B-2 Unit and Left Handed Dream. With the commercial success of YMO, Sakamoto’s solo releases served as his alternative creative outlets.

The End of Asia (1982) was a collection of traditional European (13th – 16th Century) works and Sakamoto compositions rearranged for and recorded on Renaissance-era instruments, including: recorders, harpsichord, pump organ, violins, lutes and horns. It was credited to Ryuichi Sakamoto and Danceries, a Japanese Renaissance music ensemble. Sakamoto played keys and various percussions.

Thanks to the success of the soundtrack to the 1983 film Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence, Ryuichi Sakamoto issued a few noteworthy commercial solo releases in the aftermath, the first being his Illustrated Musical Encyclopedia (1984; international release in 1986), which featured “Tibetan Dance.”

This track continued the electronic lounge sound approach from YMO’s Naughty Boys. It also featured “Field Work,” a collaboration with noted electronic synth whiz Thomas Dolby.

His 1986 Media Bahn Live CD and DVD release is a good example of a Sakamoto concert at his peak: full electric band, some solo piano, as well as loops and sound effects all blended together. The tour featured a top-notch band of seasoned vets, including bassist Ray O’Hara, Bernard Davis on drums, Ronnie Drayton on guitar, avant-garde percussionist David Van Tieghem, and Robbie Kilgore on supporting keys. With Rolling Stones backup singer Bernard Fowler leading a pair of female harmony vocalists, Media Bahn Live captures the best of Sakamoto’s commercial music sensibilities: synth pop, R&B, jazz fusion, lounge and ethnic music, linked together by his classical training and electronic music expertise. Sakamoto’s solo piano portion even includes a nod to Erik Satie, as well as his most popular song,“Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence.”

Sakamoto steps out from behind his keys to share lead vocals on “Field Work” with Fowler (37:25) and on the YMO song “Ongaku” (40:00) Sakamoto launches into the breezy lounge pop song with a decidedly more energetic beat while Fowler sings admirably in phonetic Japanese.

Neo Geo, (1987), a solo record released on CBS/Sony, melded funk and jazz fusion rock with traditional Okinawan folk melodies and replaced the black female soul singers with a kimono-clad Japanese trio accompanied by a tabla player on its title track. It was his most assertive foray into world beat and other ethnic musics at the time.

Sakamoto interspersed classical piano and strings compositions, such as “Before Long,” which foreshadowed some of the themes he would weave into his future film soundtracks.

The incongruous but ultimately perfect guest appearance of Iggy Pop on the record’s single, “Risky,” was only one of a number of musical peers that contributed to Neo Geo. The light lounge rock jazziness of Naughty Boys gains a harder and darker edge on “Risky,” while Japanese biwa, shamisen and Korean gayageum counterpoint the electric instruments and Iggy Pop’s seductive croon.

Produced by bassist and experimental “collision” music luminary Bill Laswell, Neo Geo included bass from funk icon Bootsy Collins, drums by jazz legend Tony Williams and reggae titan Sly Dunbar, guitar from session stalwart Eddie Martinez and pipa from Lucia Hwong.

Following in the same “collision” music vein of mixing ethnic music instruments and motifs with electronica and other stylistic elements, 1989’s Beauty found Sakamoto exploring pop, African, flamenco, Chinese, and techno rock combinations while enlisting additional iconic musical peers to the project. Chinese ehr-hu, African talking drums, zithers, Japanese shamisens, and a wide array of Brazilian percussion instruments were interwoven with Sakamoto’s keys and his all-star guests:

Brian Wilson contributed his signature vocals. Robbie Robertson (guitar), Pino Palladino (bass), L. Shankar (violin), Youssou N’Dour (vocals), Nana Vasconcelos (percussion), Pandit Dinesh (tabla), and New York noise rocker Arto Lindsay joined Neo Geo holdovers Martinez, Dunbar, and a host of other musicians and singers.

“You Do Me,” the single, was sung by Jill Jones. Full of funk motifs, it was probably the most commercial song on Beauty and could easily have been recorded at Prince’s Paisley Park, with its little keyboard snippets and R&B vocal arrangements tightly grooving with incessant dance beats and throbbing basslines.

With 1990’s Heartbeat and fresh off his Academy Award and Grammy Award wins for The Last Emperor soundtrack. Sakamoto’s records finally demonstrated his final transition from rock star artist to highbrow experimental composer. By this time a resident New Yorker, Sakamoto was a fixture in the downtown New York arts scene. Eschewing the rhythm section of rock and funk, Heartbeat contains mood pieces, collaborations with friends like David Sylvian, Ingrid Chavez, and Arto Lindsay, atmospheric jazz guitar from Bill Frisell, bluesy harp wails from the J. Geils Band’s Magic Dick, and New York Lounge Lizards’ founder and saxophonist John Lurie. Last but not least, celebrated avant-garde composer John Cage made a cameo spoken word appearance on the title track.

Heartbeat’s strings and horns, arranged tastefully with an orchestrator’s deft touch, showed Sakamoto’s new focus on the use of music for creating atmospheres and evoking specific emotions – not coincidentally the primary objectives for his soundtrack music, which would increasingly comprise a major portion of his subsequent musical output to the present.

While Sakamoto would continue to touch on popular music in Sweet Revenge (1994), the Latin tinged Smoochy (1995), and Chasm (2004), his composer sensibilities had so thoroughly supplanted his commercial pop song instincts that he would return to his past catalog for rearrangements of his work for different instruments in various attempts to rekindle that part of his music writing. This would have mixed critical and commercial results, such as with Three (2012). Discord (1998) was Sakamoto in New Age instrumental chamber music mode with religious underpinnings and subsequent remixes and mashups with New Yorkers DJ Spooky and Laurie Anderson.

Sakamoto’s interest in ethnic music forms steered him towards bossa nova and the music of Antonio Carlos Jobim. A critically acclaimed triptych of albums recorded with Jacques and Paula Morelenbaum: Casa (2001), Live in Tokyo (2001), and A Day in New York (2003), gave Sakamoto some respite from composing and he seemed to have genuine fun playing bossa bova with his new friends.

Jacques Morelenbaum would also join Sakamoto for UK charity NML (No More Landmines). To raise awareness over the dangers of landmines, Sakamoto composed an EP of material, including the single, “Zero Landmine.” Sakamoto brought in many Japanese musicians, including members of the band Dreams Come True, and old YMO friends Hosono and Takahashi. International musician friends who would contribute included Cyndi Lauper, Brian Eno, Kraftwerk, Bosnian singer Jadranka Stojakovic, drummer Steve Jansen, and Jansen’s former bandmate in Japan and singer/lyricist for “Zero Landmine”: David Sylvian. The song had a number of different instrumental arrangements on the EP as well as vocal versions and parts.

German musician Alva Noto also began collaborating with Sakamoto on experimental cut and paste musical works using various loops and percussion, with each one working independently and sending the work in progress back and forth. Vrioon (2004), the first of five Sakamoto/Noto collaborations, was voted 2004 electronica Record of the Year by UK’s The Wire magazine. The collection was dubbed the “VIRUS series,” as an acronym for the subsequent releases: Insen (2005), Revep (2006), utp (2008) and Summvs (2011). Alva Noto’s collaborations with Sakamoto continued through to his 2016 soundtrack for The Revenant.

As much as Ryuichi Sakamoto has been a trailblazer in electronic and world beat music, his solo piano work is of special note.

In the 1980’s, Edgar Froese (ex-Tangerine Dream) started a label called Private Music. One of their first releases was an acoustic piano CD entitled, Piano One, which featured solo piano works by Sakamoto, Eddie Jobson (Roxy Music) and jazz artist Joachim Kuhn. Sakamoto’s solo piano rendition of “Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence” became extremely popular, leading this version to become a Sakamoto concert highlight.

While self-deprecating in interviews about his piano technique, Sakamoto is clearly a masterful pianist, whose playing is disciplined, yet subtle and nuanced, with influences from Chopin, Debussy and Satie noticeable in his impressionist melodies. In fact, Satie’s, “Gymnopedies” was a regular concert staple of Sakamoto’s solo shows.

Though certainly a prolific composer for a staggering range of media, including opera and custom ringtones for Nokia, Sakamoto has frequently showcased the acoustic piano on a number of his recordings, often re-arranging some of his popular hits in different formats. His 1996 (1996) reworked his catalog for piano/cello/violin trio. BTTB (1998) (acronym for Back To The Basics) featured a number of original solo piano cuts, and 2009’s, Playing the Piano/Out of Noise was a 2-CD set that combined a solo acoustic performance of his famous film score themes, as well as synth-pop hits like “Tibetan Dance” and “Thousand Knives.”

Sakamoto has also contributed piano to other artists, most notably the solo records of David Sylvian. In Sylvian’s Secrets of the Beehive (1987), Sakamoto’s gorgeous and elegant piano accompaniment and chord voicings are the perfect counterpoint to Sylvian’s poignant lyrics, especially on the epic, “Orpheus.”

Sakamoto also contributes most of the keyboards for Sylvian’s Dead Bees on a Cake (1999), Brilliant Trees (1984), Words With the Shaman (1991) and several singles.

As a sideman keyboardist, Ryuichi Sakamoto has recorded on Arto Lindsay’s Encyclopedia or Arto (2014), Paula Morelenbaum’s Telecoteco (2008), Nine Horses’ Snow Borne Sorrow (2005), Towa Tei’s Best Korea (2003), Mick Karn’s Each Path a Remix (2003), and arranged for Lang Lang and other artists. His extensive work on fusion guitarist Kazumi Watanabe’s Tokyo Joe (1978) led to Watanabe becoming YMO’s touring guitarist and contributor to Sakamoto’s earlier solo recordings.

Film and Television Composer

With the success brought about from YMO, Sakamoto has channeled his celebrity into a film scoring career that includes composer/acting roles in Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence and The Last Emperor, the latter which garnered an Academy Award for Best Soundtrack. Other film soundtracks include Little Buddha, The Sheltering Sky, Snake Eyes and High Heels. His most recent scores were for the Academy Award nominated film, The Revenant (2016), Haha to Kuraseba (Nagasaki:Memories Of My Son) (2016), Ikari (Rage) (2017), the French film Proxima (2019) with Eva Green, and the recently released short film, The Staggering Girl (2020), featuring Julianne Moore and Kyle MacLachlan.

During a 1982 YMO hiatus, Sakamoto was approached by director Nagisa Oshima, best known in the West for his art-porn biopic of notorious murderess Sada Abe, In the Realm of the Senses. Oshima wanted to make a World War II film about a Japanese POW camp and the power dynamic between a determined Japanese commandant and the British prisoner who refuses to break.

Starring Sakamoto as the commandant and megastar David Bowie as the stubbornly stoic POW Jack Celliers, Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence also featured the dramatic debut of comedian “Beat” Takeshi Kitano (who would later become identified for his violent Yakuza roles) and Tom Conti as the title character, whose point of view narrates the film. Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence was also Sakamoto’s first international feature film score, winning the 1984 BAFTA Award for Best Original Music Score.

Easily his most famous solo song globally, “Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence” is usually performed on solo piano in most Sakamoto concerts.

Sakamoto’s first of several collaborations with David Sylvian also spawned the 1983 hit single, “Forbidden Colours,” which featured the original “Mr. Lawrence” instrumental track with additional vocals and lyrics by Sylvian inspired by the similarly homoerotic-themed Yukio Mishima novel of the same name. The song reached #16 on the UK charts.

Once he caught the bug, Sakamoto would go on to work heavily in the film and television fields, on both Japanese and international productions. In addition to the aforementioned films and shows, Sakamoto scored The Handmaid’s Tale, Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, Silk, Wild Palms, Love Is The Devil, Femme Fatale, Hara Kiri: Death of a Samurai, Gohatto, Babel, Black Mirror: Smithereens, Ni de lian, and numerous others.

Sakamoto has mentioned in past interviews that even though he was Japanese, his musical background and roots are almost entirely based upon Western Classical music. Pop, jazz and rock music only caught his attention years later. His preference for piano and strings with occasional electronic, rock, funk and ethnic music elements combined with a rare film genre eclecticism shares more than a few traits with his contemporaries, such as Hans Zimmer, Ennio Morricone, and Mark Isham.

The Last Emperor (1987) put Sakamoto into the A-list film composer category. Bernardo Bertolucci’s epic about the fall of the Ch’ing dynasty and the early 20th century history of a turbulent China won numerous Academy Awards, including Best Picture and the Oscar for Best Soundtrack (shared with David Byrne and Cong Su). The Last Emperor also won the Grammy and the Golden Globe that same year for Best Film Score.

Sakamoto would continue scoring for Bertolucci on The Sheltering Sky and Little Buddha, and would also work with Brian DePalma on Snake Eyes and Femme Fatale, and other acclaimed directors such as Pedro Almodovar, Oliver Stone, and Alejandro Inarritu.

The dedication to film scoring is something Sakamoto seems to have been destined for, and it has garnered him some of his most noteworthy achievements and recognition. According to IMDb (Internet Movie Database), Ryuichi Sakamoto’s film scores have notched 18 wins and 21 award nominations. Some notable wins and nominations in addition to the aforementioned include:

Academy Award:

2006 – Best Soundtrack winner for Babel (shared award as it was a compilation of works from different composers; Sakamoto contributions include the “Bibo no Aozora” closing theme).

Golden Globe:

2016 – Best Score nomination for The Revenant

1991 – Best Score winner for The Sheltering Sky

BAFTA:

2016 – Best Score nomination for The Revenant

1989 – Best Score nomination for The Last Emperor

Asia Pacific Screen Awards:

2012 – FIAPF Award for Outstanding Achievement in Film

Grammy Awards:

2016 – Best Score for Visual Media nomination for The Revenant

1995 – Best Instrumental Composition for a Motion Picture or Television nomination for Little Buddha.

Taipei Film Festival:

2018 – Festival Prize Winner for Best Score for Ni de lian

Tokyo International Film Festival:

2017 – Winner, Samurai Award

World Soundtrack Awards:

2016 – Winner, Lifetime Achievement Award

Sakamoto’s other awards include The Ordre des Artes et des Lettres from the French Ministry of Culture (2009); MTV Breakthrough Music Video Award for “Risky” (1987); International Samobor Film Music Festival Golden Pine (Lifetime Achievement) Award (2013 – shared with Clint Eastwood and Gerald Fried).

In 2014, Ryuichi Sakamoto announced that he had been diagnosed with oropharyngeal (tonsil) cancer and would be taking an indefinite break to focus on his recovery. A year later, he felt strong enough to return to work, and would compose scores for Yoji Yamada’s Haha to Kuraseba (Nagasaki: Memories Of My Son), Irari (Rage), and The Revenant.

Sakamoto also released another solo record in 2017, async, and another film score: The Fortress, a Korean period film directed by Hwang Dong-hyuk and starring international Korean star Lee Byung-hun (The Magnificent Seven, G.I. Joe: Retaliation, Red 2).

In 2018, documentary director Stephen Nomura Schible released Coda, a retrospective on Sakamoto’s resumption of music work during his battle with cancer, as well as his involvement with nuclear power protest activism in the wake of the Fukushima Daiichi tsunami disaster.

Ryuichi Sakamoto is a consummate musician with an indefatigable spirit. Constantly exploring new sounds, both natural and electronic, new music and cultures, his art melding these sounds to images for the world to enjoy. Even in the wake of cancer, he continues to produce, as with his latest releases, Proxima (2019) with Eva Green, and the recently released short film, The Staggering Girl (2020), featuring Julianne Moore and Kyle MacLachlan.

Acclaimed veteran violist Liuh Wen Ting, who had previously contributed viola to Sakamoto’s Snake Eyes score, recently disclosed to me that she just finished recording music for Sakamoto’s latest film score: the highly anticipated period drama Love After Love from celebrated Hong Kong director Ann Hui. She told me that Sakamoto was very friendly with all of the musicians and conducted the orchestra in strictly classical style, with no electronic or non-traditional Western instruments, at least not in the recording sessions of her participation. She also reported that he appeared in good health and was preparing to record a newly composed score for a forthcoming Japanese documentary expose on the deliberate 30-year mercury poisoning of a Japanese village that was hushed up by the government.

At age 68, Ryuichi Sakamoto seems to be in no hurry to retire. With his musical prowess still intact, his activism streak undiluted, and his steely work ethic untarnished, he is back in the game with a vengeance, and fans across the globe will eagerly await his next musical revelation.

Header image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Joi Ito.

The Gear That Changed My Life – The Bass Series

I am going to explore some bass stuff for a few columns here. It’s surprising and a little disconcerting that I haven’t explored this idea yet because I are a bass player. But I was thinking about gear that changed the way I listen to music and nothing changed my listening as much as when I started playing the bass guitar. Also I noticed in Dan Schwartz’s column in Issue 108 that Paul McGowan proposed a piece on why a bass instrument is important. I’d like to take a swing at that.

I did a column on Jaco Pastorius very early on (Issue 11). As far as bass influences go, everything for me has to start with Jaco. But since I did that already and everyone knows that guy, I’ll cover some major influences like Stanley Clarke and Victor Wooten. I know there are maybe seven readers out there interested in this topic so I’ll sprinkle these guys around. Or not.

Today we’ll go personal. In 1972 I was a guitar player who played bass. Guitar players are particularly guilty of believing that because the bass guitar has fewer strings any guitar player can pick up the bass and play it. That’s why I say I was a guitar player who played the bass. Guilty as charged. Later a real bass player named Jerry Lelancette came to a gig and pulled me aside to quietly advise me on the error of my ways, then turned me onto Jaco’s first album. Now there was a “POOF” moment. About the same time drummer Rob Fried joined our little band and not so quietly asked me WTF I was doing out there.

Before these revelations I was playing a plastic-faced 1960s era Hagstrom bass that played like barbed wire so I was not thrilled with the instrument. In 1976 my young wife and I were visiting a friend dating a wealthy wise guy. One didn’t get far into a conversation with me before I mentioned I played bass, and this dude said he had one he’d gotten in a drug deal and didn’t know what to do with it.

We went to look at the thing in his room. Lord only knows what he had in there. From under his bed he slid out a black case with the Fender logo printed across the top. My pulse quickened. Three clasps later he opened the case to reveal a brand new natural finish Fender Jazz Bass guitar.

Hey! There’s a picture of it!

Remaining nonchalant I asked the man how much he wanted for it.

“I’ll take a hundred bucks.”

This was 1976. Diana and I were 22 years old, married two years and flat broke. $100 was a ton of money. However I had honed my whimpering skill (which is how I got her to marry me in the first place) and went to work. We took the bass home that night with a prayer that the check was good.

The difference between the Hag and the Jazz kicked off a lifetime of exploration. I know of at least one band that hired me before they heard me play a note because that bass screamed “Professional Here!” It wasn’t true for a while but that’s when I really started to take the instrument seriously.

I’d like to take a moment and talk about the parts of this bass, stuff only I care about but you may have noticed and would like some clarification. For instance note the position of the thumb rest. Most of the basses I’ve seen have the rest below the strings or none at all. There was a reason Leo placed the rest below the strings but that’s a story I’ll let a reader tell.

First I removed the pickguard. Looks great without it. Then during my Jaco phase I had the frets taken out and replaced with rosewood dust. Because I play round wound strings the neck took a horrific beating and I had to periodically refinish the fretboard. But I love the sound of the round wounds and the fretless. Plus that maple neck with the natural finish body…Ooh la la.

Later I was in a New Wave band called first The N Men, then White Noise and finally The Uh-Oh Squad (see Issue 71 for more about that). I loved all three names. I changed to the Badass bridge you see below and I’ve never regretted it.

At the time I was doing most of the lead vocals. The guys finally came to me and said “Rasbo (that story in a minute), when you’re singing you are not playing in tune on that fretless. We have to get you a fretted neck.” I acquired a beautiful bird’s eye maple Precision Bass fretted neck (which I still have if anyone is interested) and installed it.

In the following years I would go back and forth between the fretted and fretless necks as events required until I got worried I would strip out the neck screw threads, so I’ve left it fretless and will from here out. Bonus, I now have the excuse to go whimper to the wife about needing a fretted bass. I have begun the process. Diane asked me with a straight face what I would do with the fretless if I got a fretted. The girl is a sketch.

Down next to the bridge is a points plate from a 1978 Harley Sportster. It was engraved by a friend of mine. Rasbo Jenks was my stage name and there is still a very small subset of humanity who know me by Rasbo. My brother owned a light and sound company named Lightning Sound and his logo was a G-clef with a lightning bolt through it. My brother was and is a really creative guy. Eventually The Uh-Oh Squad needed equipment. I sold the Sporty and funded it. In homage I swapped the points plates and mounted this one as you see here.

By 1984 the kids had started coming and it was time to grow up. I went back to school and got an engineering degree. My wife asked me at the time if I wanted a class ring. Being still a musician at heart I requested a pair of active EMG pickups instead.

The last and most heavenly change is the signature on the headstock. PS Audio, where I work, had started a record label and the mixing engineer/producer is a genius named Gus Skinas. The guy knows everybody and is very good friends with Victor Wooten, bassist specifically for Bela Fleck and the Flecktones and more generally for the world at large. Gus told me that he would bring Victor by my office the next time Wooten was in town.

This was a surreal moment. I was sitting in a management meeting at PS Audio in a room surrounded by glass looking outside. Paul McGowan said to me, “Is that Vic Wooten?” And there he was, coming in our front door with that big smile of his.

Knowing Victor was coming but not knowing when, I had brought the J-Bass in to leave in my office. Fortunately Victor is one of the sweetest men on the planet and was glad to autograph the headstock for me.

We had a wonderful chat and I told him the history of the guitar as I’ve told here. I said I’d paid $100 for it and explained all the mods I’d done. Finally I said it’s not worth what it could be because of all the changes I’d done to it.

He turned to me and said, “Well it’s worth a hundred bucks.”

Thank you Victor for making a pretty good story infinitely better. And thank you dear readers, for letting me indulge in a small personal journey.

Audio Companies Respond to COVID-19

In a recent video Steve Guttenberg aka The Audiophiliac pointed out that Magnepan, VPI Industries, PS Audio and Emotiva have remained open during the coronavirus crisis. Like most businesses, they’ve had to adapt. It prompted me to ask around about how audio companies are handling the situation. As you’ll read, some are even helping in the medical field.

I received many responses. By no means a comprehensive list, here are some of the companies that are staying open, along with their comments. (This article is longer than usual for Copper, but I didn’t want to cut what people had to say.)

Andover Audio interim CEO Peter Wellikoff told us: “While these are challenging times, with some initiatives, there are some opportunities available for Andover Audio. In an effort to be proactive to the stay-at-home order, we planned for numerous operational changes. A large amount of inventory was relocated to a new logistics facility so as to allow us to keep fulfilling orders. In addition, materials from our suppliers were redirected to this facility.

We then set work-at-home policies for all employees. Regular scheduled department meetings and meetings with key suppliers are now being conducted via Skype. If, for an extreme reason a facility visit is required by an employee, pre-approval is needed and only one staff member per department is allowed on site at any time. Obviously, protective masks and gloves are required.”

On the marketing and sales side, we have enhanced our website and social media [efforts] and it has realized a dramatic increase in unique visitor traffic. In addition, our web store has realized an exponential growth in sales. The greatest sales demand is coming from our Spinbase (an all in one audio system) and our new PM-50 planar headphones. It’s also interesting how many consumers added the optional turntable to their Spinbase order. Consumer feedback has been along the lines of ‘if I’m going to be stuck at home I might as well enjoy some music on a new cool audio system.’ All in all, I believe Andover Audio is well positioned get through these extreme conditions and succeed going forward.”

John McDonald, president of Audience notes, “Audience is fulfilling all sales by drop shipping for its dealers, direct to customers. We encourage audio enthusiasts to take advantage of this time at home and try [our] products on our satisfaction guaranteed basis.”

Black Cat Cable’s Chris Sommovigo says, “[We’re open]…but since I work alone in the workshop, I’ve got the social distancing thing nailed.”

Angela Cardas Meredith of Cardas Audio tells us: “Cardas Audio is open. Some are working from home, others in an auxiliary building sewing masks for donation to front line workers. Definitely trying to figure this out day to day.”

Andrew Regan, president, notes, “Dan Clark Audio is still open. [I’m] working from home still answering phones and shipping headphones.”

Jerry Stoeckigt, director of sales and customer relations at Eikon Audio informed me that Eikon is continuing its Standard Home Demonstration Program, which was previously in place. In this program, Eikon sends the potential customer a demo system and offers home setup phone support. After 72 hours the customer must decide if they want to keep the demo system, order a new one or return it.

Klipsch is open and is extending their friends and family 25% off sale on selected products. Part of any purchase goes to the COVID-19 Response Fund.

From Bill Hutchins, chief designer: “LKV Research is open, making phono-, pre- and power amps.”

Jeff Sigmund, President of Luxman America states: “The health and safety of our dealers, customers and employees are of the utmost concern to us. We are following federal and New York state health guidelines and are monitoring the nationwide situation.

Luxman America’s warehouse remains open. We continue to fulfill orders the same or next day when received. In addition, we are working with our valued dealers and consumers on a daily basis to answer questions and provide whatever services are needed.

Luxman America is committed to maintaining best business practices throughout our entire supply chain. While there may be some production delays, we continue at near normal manufacturing capacity in Japan. In addition, our on-hand inventory position is strong for most models.

The long term history of the audiophile community in the United States assures me that continued participation by community members, in whatever way possible, will be highly beneficial in achieving this goal.”

Wendell Diller, Magnepan marketing manager comments, “Folks, what is going on out there? Is it cabin fever? We had just put online shopping on our new website when COVID-19 hit really hard. We are getting overwhelmed with orders – especially for the Magneplanar LRS (Little Ribbon Speaker) home trial. I would love to know what is motivating customers to order now. I can only speculate from my own experience.

My wife and I are taking the advised precautions. We are not panicked or paranoid about COVID-19. However, the constant drum beat of bad news takes a toll. I noticed more than ever that music is very effective in reducing stress – especially certain classical music. I can’t say that I really enjoy classical music the same way that friends of mine do. But for me, the calming effect of certain classical music is remarkable.”

EveAnna Manley, president/co-founder of Manley Laboratories comments, “At Manley Labs our factory workers donned masks and gloves and increased sanitation practices beginning March 2. Getting on this early and having our team take the threat of COVID-19 as seriously as this warrants, I think was key to protecting the health of my employees. So far six weeks later none of my people have reported any illness. They learned to get serious about the coronavirus at work and have carried that diligence home with them.

We have a team system at our 12,000 square foot factory to ensure safe working conditions. Team One is a husband, wife, and son who all live together. They can work in the back of the factory, focusing on kitting up sets of parts in preparation for the assembly workers to come collect them and then take them home to build. Team Two is one man who is performing quality control and repairs. The two teams rarely see each other. They use different bathrooms. Where possible, doors are left open are left open so that nobody needs to touch door handles. We have plenty of hand sanitizer, soap, disinfectant, gloves, and masks, as we normally carry these in the course of normal operation.

After teams One and Two have gone home for the day, at around 3:00 pm our Chief of Operations, Gamma Ibarra, aka Team Three, reports for duty in order to test microphones and prepare shipments for the following day. Team Four consists of two brothers, and Team Five is our transformer winding specialist. We stagger the working days so that the teams are working on different days, with some teams coming in on the weekends because in these times every day seems to be the same as the next day. Our secular workers don’t mind working on a Sunday.

Everybody who can work at home is doing so, including administrative, sales, engineering, and tech support staff as well as the people doing assembly in their homes. I’ve been on a campaign for the last several years to move many aspects of our operation to the cloud and upgrading our databases, communication, and information systems. This foresight has allowed to keep us working and able to produce audio equipment in America.

Gamma and I have been easily pulling 105-plus hour work weeks as we both cover the jobs of like ten people each. We are flooded with correspondence and struggling to keep up with it, honestly. So my message to the customers out there is, please be extra-patient with us as we are working our asses off and trying to keep everybody happy! And while we might be considered an essential business, because we do provide some equipment to the broadcast chain, I know that we are also an important business to so many people who seek solace and comfort with music, either creating it in their homes or playing it back on their systems, and we are doing our best to be able to provide this humanity during this time of insanity.”

PBN Audio founder Peter Norbaek says, “we’re open – busy setting up at our new shop, but still shipping inventory. Building of new product will resume in two or three weeks.”

Paul McGowan, CEO of PS Audio notes, “PS Audio is staying open, though the majority of our employees are working from home. In order to comply with state guidelines and ensure the safety of our team members, we’ve had to move production and shipping to three shifts beginning at 4:00 am and ending at midnight. In this way we can make sure no more than two people are in a room at any one time and they can maintain proper distancing. However, we haven’t had to lay anyone off and we’re on track with new products, like the M1200 mono block amplifiers Lou and Roger (pictured) have just finished building. Stay safe and we’ll get through this.”

Reference Recordings states, “during this time of uncertainty, we want to assure you that we are here for you. Music is so important to help uplift our spirits. Our small business thanks you; your purchases support our artists and make new releases possible. Our owners/employees are working hard to package and ship your orders, but due to the shelter in place situation there may be minor delays. Thank you for your patience and understanding, and we hope you stay safe and healthy.”

Schroeder Amplification and Schroeder HiFi “are still open. No foot traffic but orders are coming in and shipping out,” notes owner Tim Schroeder.

According to Keith Pray, general manager of TEN (The Enthusiast Network, publisher of Stereophile), “Just about all [companies] are open from what I am seeing on my end. Reduced staff, temporary layoffs and tightening of the belt is what I am seeing.”

Christopher Hildebrand is the owner of Tektonics Design Group, parent company of Fern & Roby. He told me about his efforts in both the medical and audio fields. “To give some background: I started Tektonics Design Group 17 years ago, as a contract design and manufacturing firm. After getting our business established with our regular work, I wanted to explore some of my own ideas and started Fern & Roby as an in-house product line. While Fern & Roby has grown we have continued to do contract manufacturing at Tektonics for other audio companies, contractors, and a couple of medical device manufacturers. Our basic purpose at Tektonics is to solve problems and make things for people.

With all that has been going on, the first thing we had to do to stay in business when it was clear this was a dangerous situation was to figure out how to keep everyone safe. We have had an open door policy and welcome a lot of interaction between our staff, but this just wouldn’t work in this new and scary context. We have a 20,000 square foot shop with a team of six talented people so we have plenty of room to space out, but under normal circumstances everyone would be moving around freely throughout the shop.

The first thing we did was to clearly define smaller teams and use separate entrances to our work zones. We wipe everything down when we come in at the beginning of the day, and again at the end. In a place where you touch tools, materials, and machine interfaces all the time, the only choice possible is to limit the number of people in each process and then clean the work if they move between teams. We also advanced a project to build a shipping and receiving room with its own new entrance for our shippers to use. This is helping us isolate people and products coming into and going out of the building and allowing us to unpack carefully and clean everything before we bring it into our space. We also carefully clean and package products as they go out to our vendors and clientele.

Once we got our own processes nailed down, I started thinking about what was going on in the current situation at large and what we could do about it. I reached out to friends we work with in the product engineering and industrial design community to ask if we could pool our resources to help in some way.

One of them mentioned that they had designed a respirator several years ago for a New York firm, but it was in limbo around FDA approval. The gist I got from our conversation was that being able to jump start something to get it going would be a long shot. Honestly, after looking into it and thinking about it more, I understood why. Making things that aren’t proven through a rigorous process can kill people instead of help.

I then got buried working on the Small Business Administration paperwork we needed to submit but about a week later (felt like a year…), my friend contacted me to ask if we wanted to help make six sets of prototype valve mechanisms to submit for an expedited FDA approval. In the past week we completed the six sets of 10 different parts, from machined and turned polycarbonate. We sent them out on Saturday, April 11 via next day air and we are waiting to hear what happens.

Since we are already in the saddle, we will likely be a part of the production run to make 1,000 respirators in about 30 days. This is about 10,000 parts and honestly, way too much for our shop, so I pulled in some colleagues in the Richmond, Virginia machine shop community to help us. If we get the job, I will be managing a group of firms to manufacture the parts in time to do some good for the people up in New York.

Our team’s work will be part of a larger effort managed by a much larger contract medical device manufacturer and honestly at this point we don’t have a great deal of visibility of the road ahead. We just let our contact know that we are ready to go whenever they need our horsepower. Even if we don’t get to be a part of that effort, we are glad to have contributed in some way.

Being nimble, responsible, and willing to help is at the core of our day to day business model and I feel very fortunate that we’re able to do something like this, turning from our normal type of work to something deeply relevant and practical for healthcare workers and their patients. Existing in the manufacturing environment in the US has sometimes felt like a tough path to follow but it is situations like this that reinforce my view that capable, local manufacturing can be a very powerful resource for society and I hope we see more manufacturing come back to the USA. We are still filling orders for our audio manufacturing clientele like Linear Tube Audio and DeVORE Fidelity, as well as our own work for Fern & Roby.

Beyond our clientele, we have a lot of friends in the audio industry. I have been thinking about how they are doing, about the industry’s challenging prospects for finding some near-term normalcy, and about the challenges of running a small manufacturing business even when things are fine. I hope people out there are considering buying the products they have been planning on for the past year or two; if we want great small businesses to be around when this is over, we need to support them now. I am hopeful about this because people in our market love the nature of the work and we are all passionate about our community.

I’m very proud of the work we do in the medical industry but I am also proud to be a part of the audio industry as an OEM (original equipment manufacturer) and parts supplier. In this crazy world we need not only respirators and masks but also the essential equipment to enjoy great music with, so go buy something from a business you care about!”

Roy Feldstein, CTO at Audio Den says that “VANA is open. We’re handling drop shipments for our dealers who can’t open their showrooms.” VANA imports brands including Atlas Cables, Audio Physic, E.A.T., Marten, Okki Nokki and Revolv.

In Issue 108 Jay Jay French interviewed VPI Industries president Mat Weisfeld about his company’s efforts in switching from making turntable products to hand sanitizers and face masks. Some excerpts from Weisfeld: “I realized that we had all the ingredients [to make hand sanitizer] because we make vinyl cleaning fluid. We have the stations for bottling it, we had the alcohol, we had the 1-ounce bottle containers. We started to reach out to other suppliers and at that point I said that this product was going to be made by us for no profit. It would all be distributed for free.

We put up a post on the New Jersey Monmouth County Facebook page and were flooded with 500 emails overnight. I knew it was real when I had hospital administrators reaching out to me.

I am delivering it myself. I even had to meet late at night with a hospital administrator in a parking lot of a QuickChek [convenience store]. She had to go out on a limb because she needs this!…We have even had walk-ins to our factory and we had to set up a pickup area outside our front door for all the safety reasons.

The decision [to make face masks] was made…when we realized that we had the materials left over from when we were making [turntable] dust covers. We had supplies and materials like plastic to make DIY face shields. We didn’t have elastic but we are using the flat Shinola turntable belts as a headband. We [now] split [our] time between making turntables and the sanitizer and masks.”

Owner Jeff Wells says, “Wells Audio is still open. Actually business has been better the last two months than in November, December and January. Weird, huh?”

“Wolf Audio Systems is open for business!” notes Fred Parvey, one of the company’s founders. He also points out, “House of Stereo [which Parvey is involved with] is open for business and we ship anywhere in the world.”

Other audio companies who contacted me and advised that they’re open in some capacity are: Alta Audio, Audio-Technica, Daedalus Audio, Emotiva, Heatshrink, HIFIMAN, Lenbrook (NAD Electronics, PSB Speakers and Bluesound), Kanto, Kimber Kable, MQA, Music Hall, NOLA Speakers, Pangea Audio, Periodic Audio, SVS, Synergistic Research, Tributaries, WattGate, WBT and Wisdom Audio.

Ninety Minutes and Three Encores

It’s New Year’s Eve in the mid-seventies. It’s after the gig, not yet midnight, and I’m driving the group back to the hotel in a Hertz rental car. The Dayton airport Hyatt isn’t the most upscale hotel, but it’s not a dive either. Besides, the band has a flight to Baltimore tomorrow, January 1, so it is convenient.

The band are the British rockers Wishbone Ash and so far the tour is going well. They are headliners playing coliseums and the band is tight, and they are really cooking. Their albums are big sellers: Wishbone Ash, released in 1970. Then came Pilgrimage (1971), followed by Argus (1972), Wishbone Four (1973), There’s the Rub (1974) and New England in 1976. They are noted for their use of twin lead guitars playing in harmony (like Dickey and Duane in the Allman Brothers) with a mixture of hard rock, blues and other influences to create a unique progressive rock sound. Iron Maiden, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Thin Lizzy and Metallica have cited Wishbone Ash as an influence.

Wishbone Ash in 1976. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Wishbone Ash in 1976. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.The other band on the tour, Wishbone’s opening act, is Eric Burdon and War. War is a mostly black fusion funk group with a smooth rhythmic sound. The only other white guy in the group besides Burdon is harmonica player Lee Oskar, and he’s not American, he’s from Europe. Lee’s wailing harmonica playing and especially his soloing fits beautifully with War’s funk/rock/Latin sound. Another unusual addition to War is the conga/percussion player, an older guy, Thomas “Papa Dee” Allen. He had played and toured with Lenny Bruce. For Lenny, Papa Dee was punctuation, Bada Boom.

This is before War had their own breakout hit records and went out on their own without Burdon. When War did go on tour as headliners. They had a string of hit singles and successful albums, with hits like “Cisco Kid,” “Low Rider,” “Me and Baby Brother,” “Why Can’t We be Friends” and the smash, “The World Is a Ghetto.”

After dropping my coat on the bed and hiding nearly $8,000 in cash in my room, I hit the hotel’s hallway looking for the party. Everyone, including road crew from both bands, has rooms on the first floor. For this night I booked 17 rooms and because of that bulk booking, I was able to negotiate the free use of a meeting room for our New Year’s Eve party.

I walk into the meeting room. Eric is there and he kind of knows me from six years earlier when we were neighbors in Laurel Canyon. Back then Eric was always on tour with the Animals and I hardly ever saw him. The Animals (later, Eric Burdon and the Animals) were part of the 1960s British Invasion and they had hits, boy did they have hits. “The House of the Rising Sun,” “Help Me Girl,” “Mama Told Me Not to Come” (written by Randy Newman and much superior to Three Dog Night’s later version), San Franciscan Nights,” “Sky Pilot” “When I Was Young” and “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood,” and those are just some of them.

Eric Burdon in 1973.

Eric Burdon in 1973.As I enter the big meeting room Eric walks over to me and, while wishing me a Happy New Year, hands me a Quaalude. Eric Burdon and War had joined the tour as Wishbone’s opening act just after Christmas, and what a week it’s been. Just one example:

A few days previously we were playing Dothan, Alabama. The morning after the gig both groups are at the Dothan airport. All of us are walking across the tarmac to the Piedmont Airlines plane. As we’re walking to the boarding steps we pass two Alabama state troopers leaning against their patrol car. They’re both big men, six foot six and around 250 pounds, in their twenties and athletically built, probably former college ballplayers.

As we walk by them one of them says, “nice show last night, Eric!” Then he shouts out a slur against some of the band members. Eric gives them the finger and says “screw you.” Although both the troopers laughed, I won’t lie; considering the time and the place I was more than a little unnerved by this.

Everyone boards the plane and Eric is wired up from this exchange. It doesn’t help that he is so drunk and belligerent that he won’t take his seat. The pilot calls the tower, the tower calls the cops and don’t you know it, those same two state troopers board the plane. One cop grabs Eric by his armpits and the other grabs his legs behind his knees, and the two of them carry Eric cussing and fussing off the plane, which takes off without him.

Forward to 7:30 that night and I’m backstage at the Coliseum in Cincinnati, Ohio. Both bands have done their sound checks and Eric is still nowhere in sight. (Remember, this was in the days before cell phones.) This is a real problem.

Eric and the band are due on stage at 8:00 sharp to open the show. They get 50 minutes including encore. After that, there are 10 minutes to get the opener’s equipment off stage. Then Wishbone Ash hits the stage at 9:00 and plays for 90 minutes. Their set is followed by three encores, finishing up just before 11:00.

They have to be done before 11:00 because all arenas in America are union halls. If they play one second past 11:00 it’s overtime, and that becomes an unexpected cost to the promoter. In fact, it would cost the promoter a lot of money. If that happens, word gets around to other promoters, and it affects a band’s bookings. Bands are warned about that, so it rarely happens.

Where the f**k is Eric? I’m worried, and I’m not ready to even consider that War could play without Eric. Would that even work? (Within a year I got my answer, but at the time, Eric was the star of the show.) I do not have a good Plan B.

Not sure of my options, I open my briefcase and pull out my Rand McNally map. I see that Dothan, Alabama is 660 miles south of Cincinnati. I don’t know how Eric is getting to Cincinnati or if it’s even possible. For all, I know his butt could be sitting in jail.

At 7:55 a station wagon speeds down the Coliseum’s loading ramp and screeches to a stop just thirty feet from the stage. Behind the wheel is Eric’s road manager, Big Jim Grant.

Eric is inside lying flat on his back. He pushes himself up to a sitting position, and, holding on to the door, climbs out the back of the station wagon. He’s still drunk as a lord. Eric steadies himself against the side of the vehicle and then lurches over to the stage steps, holding onto the handrail. War comes filing out of their dressing room and joins him. Together they climb up the stairs onto the stage.

Eric says “Hello!” to the audience and vaguely mumbles that he had a big adventure getting to Cincinnati. They launch into “Spill the Wine.” They hit it full tilt. They’re kicking ass! This is the same guy who could barely get out of a car five minutes ago. They follow it by “We Gotta Get Out of This Place.” The place is going nuts. It’s one of those fantastic rock and roll moments.

Spying Big Jim Grant across the room, I walk over. Smiling, the big guy turns towards me and I ask, “how the hell did you make it to Cincinnati on time?”

He tells me that the troopers didn’t arrest Eric. In fact, once they got him back to the terminal, they laughed, helped him stand up and told him he was free to go. “They even gave me directions,” said Jim.

It seems they were at the concert the night before, moonlighting in uniform as concert security. They really liked Eric’s music and thought he was cool. So, they cut him some slack even though he was roaring drunk at 7:15 in the morning. But, hey he’s a legend and English and most important, he is a Rock Star.

Barreling out of the airport, Jim took local roads north to Birmingham, then got on the interstate I-65 north to Louisville ,switching to I-71 Northeast straight into Cincinnati. Hauling ass and stopping just once just south of the Tennessee state line to get gas, pee, grab a bite to go and oh yeah, buy a bottle of Southern Comfort. Eric, Jim says, is all stretched out laying there like he’s dead in a poor man’s hearse. Well, actually he’s drinking and falling asleep, then waking up and drinking again. Jim says this cycle happened at least three times.

Feeling the pressure of getting to the gig with the clock ticking it must have been some sight. Big Jim speeding through the Deep South with a drunk Englishman lying semi-conscious in the back of a rented Avis station wagon. Insanity. By the grace of the rock and roll gods, they somehow breezed through.

By today’s standards our behavior would not cut it, but back then it was sex, drugs and rock and roll. The causality rate was high, but that was the life we embraced. Like soldiers in combat, no matter what the obstacle, we get the job done.

Italian Progressive Rock, Part One: PFM

The major British progressive rock bands of the late 1960s and early 1970s found receptive audiences throughout Europe, with perhaps none more enthusiastic than the Italians. Italy’s symphonic and operatic heritage was undoubtedly a factor in the acceptance of a new genre blending rock with elements of classical music.

Rock musicians in Italy took inspiration from the likes of King Crimson, Yes, Genesis, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer, among others, and those bands had great success touring the country. The most famous Italian progressive band, and one of the very few to see their records released in the United States, was Premiata Forneria Marconi, or PFM. Their name was taken from that of a small-town bakery, Forneria Marconi, to which they added Premiata (meaning “award-winning”).

Guitarist Franco Mussida, keyboard player Flavio Premoli, and drummer Franz Di Cioccio had been backups for many Italian pop acts prior to forming their first band I Quelli, with bassist Giorgio Piazza. The addition of violin and flute player Mauro Pagani gave them a much broader musical palette, leading to their new incarnation as PFM.

They released two fine albums on the Italian Numero Uno label, Storia di un Minuto (“Story of a Minute”), and Per un Amico (“For a Friend”), which were sung in Italian. Storia was an unprecedented success, topping the Italian record charts. When Emerson, Lake & Palmer toured Italy, Greg Lake took notice of the band and signed them to ELP’s own new label, Manticore Records.

In 1972, the very first release on Manticore was PFM’s Photos of Ghosts, a compilation of songs from their two Italian LPs. The tracks were re-recorded in England, with new English lyrics by Peter Sinfield (lyricist for King Crimson and ELP). The album garnered a fair amount of airplay on FM underground stations at the time and even cracked Billboard magazine’s Top 200.

One track, “Il Banchetto” (“The Banquet”), was left in its original Italian. A strong influence of King Crimson can be heard in the guitars and drumming. In the middle, you’ll hear a quirky synthesized orchestral passage somewhat reminiscent of Switched-On Bach, followed by a very nice acoustic piano solo in the style of Keith Emerson.