I have recently been introduced to the American composer Mason Bates, and in particular an album of three of his symphonic works recently released by the San Francisco Symphony. Indeed, the first of these – The B-Sides – was commissioned by conductor Michael Tilson Thomas on behalf of SFS, the commission reportedly being proposed by Tilson Thomas during the intermission of a performance of Tchaikovsky and Brahms symphonies. The album is called Mason Bates – Works For Orchestra, and I highly recommend it. But my daughter’s cat – not so much. She will normally curl up quite happily on my lap whatever I am listening to, but upon hearing the first few bars of “Broom of the System” she slinked out of the room with her ears back and her tail between her legs!

Bates’ music is possessed of the uneasy sonorities of a movie soundtrack set in the isolation of deep space. It is both unsettling and captivating at the same time. At various times it evokes Alien, 2001 – A Space Odyssey, and Close Encounters Of The Third Kind. But a sense of brooding foreboding seems to infuse everything. Even as it breaks into the gusto and swing of big band jazz, this is quickly interrupted by ominous rumblings of thunder, or howling winds which transform into weirdly gurgling water. Under Tilson Thomas’s assured and sympathetic touch these unusual effects transition seamlessly and naturally. The unsettling nature of The B-Sides is supremely well-handled, and not allowed to descend into melodrama or caricature. In particular, the third movement of The B-Sides, “Gemini in the Solar Wind ”, is some sort of eerie communication between an astronaut and ground control, featuring actual samples from Ed White’s space-walk ‘discussions’ with Houston during the Gemini 4 flight of 1965, and we feel nervously concerned that the fates can have nothing good lined up for Major Tom. It’s strangely strange, yet oddly normal, and most unsettling in a totally darkened listening room. [And of course the fates did have nothing good lined up for Major Tom. Ed White was one of the three astronauts who perished in the 1967 Apollo 1 fire.]

Both Liquid Interface and Alternative Energy express somewhat dystopian viewpoints with extreme global warming as a common theme. In the former, glaciers calve in the Antarctic, the oceans rise and drown New Orleans in a storm, and we end up in the same watery wilderness that nearly submerged Kevin Costner’s career. In the latter, our need for energy takes us from an innocent time at the turn of the 20th Century, via a particle accelerator and a Chinese industrial wasteland, to an imagined tropical Reykjavik, inhabited by the last remnants of the human race. With such a clear programmatic basis, a good interpretation requires a strong hand on the narrative arc. Even though Bates characterizes these Works as Symphonies rather than Tone Poems – and indeed they are structured as symphonies – it is my view that they are best treated as Tone Poems. Of course, a conductor is free to chart his own interpretive course if he feels a kinship with it, but he still needs to deliver on his vision.

Is this classical music or something else? There are times when it is purely orchestral – and fits into the classical mold in both form and structure. There are other times when only electronic sounds are present, or purely modern ensembles such as big band jazz. We tend as music consumers to want to package our music into neat groups. Sure, there is crossover music which melds disparate forms, but generally such works adhere to a consistent affectation throughout the piece. Mason Bates is different. Taking his inspiration from the way a movie soundtrack is put together he moves seamlessly from one soundscape to another in a style which comes across as remarkably organic and natural. Still, it fits better in the ‘classical’ box than in any other.

For a conductor who can do Mahler with the very best of them, Michael Tilson Thomas does display a keen sensitivity to the Mason Bates idiom, but overall has a tendency to hold the music back too much. This music carries an ambiguous yet overt emotional payload. Tilson Thomas allows the tension to build very well, but doesn’t provide an appropriate release. Much as he guides The B-Sides with a sure hand (he did commission the piece after all, so you’d expect him to develop an affinity for it) he is less sure where he wants to go with Liquid Interface or Alternative Energy. The net result is akin to reading a gripping novel, and finding that some swine has torn out the last chapter.

Naturally, for music inspired by the modern idiom, rhythm is a powerful element, and needs to be treated appropriately, unlike with Beethoven, say, where a heavy hand on the rhythmic aspects can overshadow the textural and structural subtleties. There are times when the syncopated rhythms – indeed the overall phrasing – of Bates need to be played in such a way as to emphasize the ‘groove’. Listen to the second movement “Chicago (2012)” of the Alternative Energy symphony, and compare Tilson Thomas’s reading of it to Bernstein’s legendary 1958 performance of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. Now I’m not suggesting that one should expect Tilson Thomas’s Bates to be “legendary”, but it does illustrate very cleanly the areas in which his Bates is wanting.

It is interesting to compare and contrast Tilson Thomas’s effort on Works For Orchestra with Gil Rose’s interpretation of Bates’ ‘Mothership’ with the Boston Modern Orchestra Project (on BMOP’s own label). This conductor/orchestra pair is naturally more attuned to the contemporary music idiom, and thus the performance is more organic, and more immediate. But the BMOP does not possess the depth of sonority of the San Francisco Symphony, and Rose seems to have less to say about the music, and as a result it has a tendency to come across very much like a film-score, wanting for substance beneath a superficially glitzy exterior. I expect that I will return to that album less frequently than I will the Tilson Thomas.

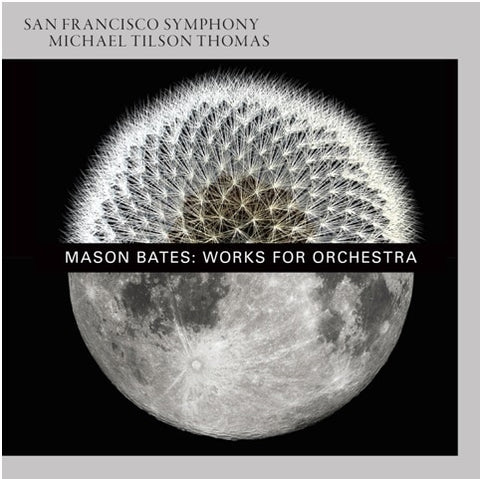

While my comments may come across as overly critical, let me be clear. I find Works For Orchestra to be deeply compelling. The recording is crystal clear, the music is brilliantly conceived and finely played, and – for what it’s worth – the cover art is seriously cool! Bates’ music shows genuinely original compositional skills without the appearance of having shoe-horned the modern artifice in for its own sake. The various electronic sounds all integrate organically, an accomplishment which, arguably, no other composer has delivered as convincingly. Notwithstanding the electronica his basic orchestration is competent – bordering on the extremely good, actually – but is neither novel nor avant-garde. Which is not a bad thing – I rather like it. Works For Orchestra was, naturally, playing while I wrote this. After the album finished, the next album which popped up for whatever reason was “Pohjola’s Daughter”, by Sibelius. The transition was remarkably seamless and natural, which I thought was very interesting.