Loading...

Issue 93

Batting .800

Rodney Crowell – Texas

I grew up in the red clay hills of rural North Georgia; country music is in my blood, even though it probably represents a fraction of a percentage point of my music collection. I was raised where the preachers of dirt-poor Baptist churches would damn rock and roll music to Hell every Sunday, then climb behind the wheels of their Ford Fairlanes and crank the Hank Williams and George Jones singing about boozing and womanizing. I never quite understood that dichotomy as a young man. During the early years of my life, when my dad was very ill, we stayed a lot with my Uncle Edwin, who listened to nothing but a steady diet of Porter Wagoner and Dolly Parton; the Grand Ole Opry is etched into my brain. And prior to my dad’s illness, my mom actually performed on the local AM radio station playing guitar and singing country and folk songs, and later on, insisted we watch Hee-Haw every week.

I first became aware of Rodney Crowell as a member of Emmylou Harris’ Hot Band back in the seventies; already an established songwriter at that point, he was soon writing songs for Nashville’s royalty. Over his career, he’s had no fewer than five of his songs hit No. 1 on the country charts; I saw him perform twice as a member of Emmylou’s touring band in the late seventies, which was always an incredibly entertaining show. God knows I was in love with Emmylou Harris, and Crowell wrote several of her signature songs that were really brought to life in concert, like “Ain’t Living Long Like This” and “Leaving Louisiana”. He soon stepped out and started performing and recording his own songs, but still collaborated on albums with Emmylou and countless other Nashville performers over the course of his career. His music has strayed frequently from true Country to more of the Americana genre over recent years. I have to admit that I’m much more a fan of Rodney Crowell’s talents as an amazing songwriter and performer than as a singer; his albums are generally well-recorded, and usually with a stellar cast of performers and guest artists. But, for me, his voice is more acclimated for those “pure country harmonies” with amazing singers (like Emmylou Harris) than that of a lead singer. It’s not really a “strong” voice, and it doesn’t have any of the quirky characteristics that make other singers (like Willie Nelson) so interesting.

All that said, his new album, Texas (Crowell hails from Houston) is all of the above, pretty much in a nutshell, and probably the outstanding country music release of 2019 so far. His twenty-first studio album, it features a stellar cast of contributors, ranging from Willie Nelson, Lee Ann Womack, Billy Gibbons (ZZ Top), Lyle Lovett, Vince Gill, Steve Earle, and even Ringo Starr thrown in for good measure! And even though there are some finely crafted tunes within, it pretty much, for me, sums up my assessment of Rodney Crowell’s career: excellent songwriter and performer, but God bless him for having the fortitude to continue to pursue a career as a solo artist. The best songs on this album are where he’s harmonizing with his notable guests, like “Brown and Root, Brown and Root”, where the blending of voices between Crowell and Steve Earle is simply magical, undeniably resulting in the album’s biggest highlight. Most of the songs here seem really promising, but just sort of fall short; an extra verse, or perhaps a more extended instrumental bridge would serve the music well. Still, his shared vocals with Willie Nelson, Ronnie Dunn, and Lee Ann Womack are pretty enjoyable on “Deep in the Heart of Uncertain Texas”, which is a really enjoyable song and ought to get a good bit of airplay on country radio. Another real highlight is “The Border”, a real downer of a song in an album of otherwise upbeat tunes. It’s a minor-key assessment of all the recent craziness focused on the border between the US and Mexico, and Rodney really nails the realities of the poor folk trying to find a better life and the risks they take to try and make it happen.

Despite my personal reservations, Texas is a really good album with some really good work by a boatload of great artists. That could easily have been a great album. And, hey: Rodney Crowell was just inducted into the Texas Country Music Hall of Fame! Recommended.

Rodney Crowell Records, CD/LP (download/streaming from Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Google Play Music, Spotify)

Sleater-Kinney – The Center Won’t Hold

All-girl group Sleater-Kinney, consisting of Corin Tucker (vocals, guitar), Carrie Brownstein (vocals, guitar), and longtime drummer Janet Weiss, was one of the indie rock mainstays from the Pacific Northwest during the mid 1990’s to mid 2000’s. Critical darlings, they regularly won indie best-of polls and only increased their legend with each successive studio release. 2005’s The Woods was another critical success, featuring a denser, more heavily distorted sound that reflected changes in the band’s direction during their long stint opening for Pearl Jam’s 2003-2004 tour. Where Sleater-Kinney frequently—on record and in concert—stretched out into more extended set pieces. And suddenly, without explanation, Sleater-Kinney went on a decade-long hiatus. Carrie Brownstein was deeply involved in writing and acting in her collaboration with Fred Armisen in the Portlandia series on IFC. And the various group members remained active in other side projects throughout their absence from the forefront of the music scene.

Sleater-Kinney’s long hiatus ended in 2015, with the release of the album No Cities to Love, their eighth studio album, which was met with much acclaim and very positive critical reception. The New York Times review described it as the “First great album of 2015”, and noted that they’d honed their sound down closer to the three-minute post-punk songs of their beginnings. All working toward making the release of the new album, The Center Won’t Hold, one of the most highly anticipated releases of 2019. The album’s title already seems highly prophetic of their future prospects; drummer Janet Weiss announced her departure a couple of months before the new record’s release. Produced by St. Vincent (rumors abound that her involvement precipitated the departure of Janet Weiss), the album continues with their exploration of a more abbreviated song form, with some of the resulting tunes quite “poppy”, to say the least.

It’s really quite sad for me, the departure of Janet Weiss; her excellent drumming is pretty much the rhythymic core of this album. The title track and opening cut, “The Center Won’t Hold” unleashes a powerful drumbeat intro, soon accompanied by searing guitars. With both Brownstein and Tucker repeating the title line in a slow, rhythymic fashion that’s suddenly interrupted by a single piercing guitar note. This suddenly erupts into a chaotic minute and a half of the two singers screaming the same phrase over surprisingly melodic power chords into an abrupt ending, with Weiss just pounding those skins relentlessly throughout. Which happens with just about every song on the album. That is, ending abruptly. St. Vincent’s slick production is very appropriate with the eclectic song selection, which, while retaining much of their post-punk aesthetic, remains very melodic and “power pop-ish”. Many of their songs are presented as statements of where the band stands in the current political environment in the US; Carrie Brownstein, in a recent NRP interview with the band, basically stated that while none of the songs are specifically anti-Trump, Sleater-Kinney is most definitely an anti-Trump band. In the song “Ruins”, they ask, “Do you feast on nostalgia? Take pleasure from pain? Look out, ‘cause the children will learn your real name”. Doesn’t take much imagination to guess who that’s directed at, huh? At 5:18, it’s the longest song on the album.

The Center Won’t Hold is an outstanding album from Sleater-Kinney; despite the departure of Janet Weiss, Brownstein and Tucker insist they’ll soldier on. Let’s hope so, they’re making some of the most intelligent, tuneful, and listenable post-punk/pop currently out there. Very highly recommended.

Mom + Pop Music, CD/LP (download/streaming from Amazon, Google Play Music, Tidal, Qobuz, Spotify)

Kim Wilde – Aliens Live

I won’t apologize here—I freakin’ loved the eighties. Most of the major changes in my life that pretty much helped sculpt who I am happened then; I took my first job in the printing/publishing/advertising industry, I met my wife, moved to Atlanta, and started my family. But mostly, I attended a lot of kick-ass concerts and listened to a lot of really great music. The friendships I forged and the fun that I had during that period are still for me emblematic of what I consider the “Good Old Days”.

Kim Wilde was a mere twenty years old when she hit the big time with 1981’s “Kids In America”, and spent the next year pretty much as MTV’s “It Girl”. You couldn’t turn on the television without seeing one of her videos. I have to admit that I crushed heavily on her; I found her mix of New Wave with Punk and Power-Pop sensibilities pretty irresistible, not to mention her serious cuteness. And so did basically the rest of the world, where she went on to sell 30 million albums over the course of her career. Her only other big splash on this side of the pond was with 1986’s remake of the Supremes’ “You Keep Me Hanging On”, which I also loved. Her star continued to burn brightly in Europe and beyond, even if she remained mostly a footnote here in the US.

So when I saw the first notice of the impending release of this, her first live album, I was mildly intrigued—though I’ve gotten cynical over the years about “period” artists who try and strut it back out thirty years later. Better in my book to remain a cherished “one hit wonder” memory, than to try and cash in one last time; boy, was I wrong. All the hits are here; a lot of the songs from her first few albums that I merely considered very listenable actually charted outside the US. Plus, there are a number of new songs here, including “Kandy Krush” (I know, it sounds ridiculous!) and “Birthday” that amazingly manage to channel a lot of the New Wave hipness that so rocked the eighties for me. And it doesn’t hurt that she’s got a crack group of musicians backing her up, and that the recorded live sound is impressively good. As much as—in concept—I wanted to hate this album, I just couldn’t do it! Her voice still evokes that sexy/kittenish/coquettish vixen I always imagined from the eighties, and her delivery of the songs I know and love is remarkably unchanged from the studio originals, retaining most of its potency and edge. Pretty astonishing for someone who will turn 59 this year. Recommended, especially if you’re an eighties junkie like me.

Ear Music, CD/LP (download/streaming from Amazon, Google Play Music, Tidal, Qobuz, Spotify)

Jon Batiste – Anatomy of Angels: Live at the Village Vanguard

Jon Batiste is probably most well known as the music director of The Late Show with Stephen Colbert; aside from that, he actually has a pretty impressive musical pedigree. He was born into a musical family that included New Orleans musicians Lionel Batiste and Harold Batiste, and played drums in the family band, the Batiste Brothers Band. He switched to piano at age eleven, and eventually graduated from the St. Augustine High School in New Orleans, where he steeped himself in the New Orleans musical tradition. He later earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Julliard. Anatomy of Angels: Live at the Village Vanguard is his twelfth studio album, and he is a self-professed disciple of Thelonious Monk. Despite all that, I have a hard time taking him seriously; I just can’t get beyond that stupid-ass keyboard/horn/whistle thing he plays every night on Colbert’s show. I find it…offputting, to say the least.

The tunes here are a mix of self-penned originals and standards; the whole affair clocks in at just over 38 minutes, making this more of an EP than anything. The audience response is very polite throughout the entire performance. Jon Batiste is a very technically proficient pianist, but I compare the experience of listening to his playing as I pretty much heard everyone describe Wynton Marsalis’ first few discs way back when: incredible technician, but very little soul, and very derivative. He had yet to earn it. Very little of what I heard here moved me the way so much of the jazz I love does. And I freaking adore Monk. Jon Batiste still has to earn it. I’d pass if I were you.

Verve Records, CD/LP (download/streaming from Amazon, Google Play Music, Tidal, Qobuz, Spotify)

Tom Waits – Small Change

In recent years, I’ve slowed my tendency to rush out and acquire the latest remastering of any particular artists’ record catalog; that said, if it’s an artist I particularly love—like Tom Waits—I’ll cave in when the right opportunity presents itself. That happened a week ago when I was visiting in Charleston, SC—there’s a favorite record store there, Monster Music—that always has a superior selection of new and used LPs and CDs across a staggering array of genres. A couple of Tom Waits’ discs are definitely on my desert island list, and frankly, the currently available Warner/Asylum CDs are a shade lackluster in terms of sound quality. Monster had the newly remastered Epitaph/ANTI Waits catalog title CDs for $10 and the LPs for $20, so I caved and bought both versions of Small Change, his landmark album from 1976. To see if there’s a significant difference between the CD versions, and mainly just to check out the pressing quality of the LPs. Which at $20 is significantly less than the $30 average for new LPs these days.

There’s not a bad song on Small Change, where Waits wheezes and boozes his way through classics like “Tom Traubert’s Blues”, “The Piano Has Been Drinking (Not Me)”, “Invitation to the Blues”, “Bad Liver and a Broken Heart”, and “The One That Got Away”. A stellar backup cast that includes the legendary Shelly Manne on drums and Lew Tabackin on sax provides the perfect touch of jazzy authenticity to the proceedings. The great news is that the sound quality is head and shoulders above the Warner version. It’s obvious from the opening notes of “Tom Traubert’s Blues”; there’s much greater clarity in the sound, with the Warner version sounding more congested in comparison. The individual players are more clearly deliniated in the soundstage, and you can virtually reach out and touch Tom Waits; his presence on a CD has never been more visceral and realistic. As the orchestra fades in the close of this song, you get a much greater impression than I’ve ever sensed that you’re actually present in the recording space with the players. It’s eerily good, and almost like listening to this classic disc for the very first time.

Waits and his wife Kathleen Brennan both took part in the remastering process, and my experience with this first disc bodes extremely well for the remaining catalog. And the possibility of my acquiring the remaining discs. The LP also sounds magnificent; I felt it shared the superlative sound exhibited by the CD version, although it’s not abundantly clear whether the LP is mastered from the analog tapes—if they even exist. Not sure if Waits’ catalog was part of the big Universal fire that’s been all over the news of late [including this piece in Copper—Ed.] , but I wouldn’t be too surprised (who knows, maybe Waits’ had safety copies of all of his tapes). It’s pressed on perfectly flat and extremely quiet 180 gram vinyl, and for an extra $15, you can get it pressed in translucent blue wax. Of course, there’s no free lunch here; as great as the sound quality is on both LP and CD, the packaging was…somewhat lackluster. The CD came in a digipak—which is usually fine with me—but the print quality was somewhat washed out and faded looking (it would never have gotten through QC at my plant!) The same is true for the LP’s jacket; a bit more care could have been taken with the finished product, although I’m totally happy with the sound of the LP, and that’s what ultimately matters. Highly recommended—if you’re a fan like me, you’ll love the new remasters.

Epitaph/ANTI Records, CD/LP/Limited edition LP in colored vinyl (download/streaming from Amazon, Google Play Music, Tidal, Qobuz, Spotify)

Emily Remler: Eight Great Tracks

When Emily Remler was a kid in Englewood Cliffs, NJ, she tried out her brother’s Gibson guitar and loved it. Soon she could figure out 1960s rock songs by ear from the radio. Although she thought of music as just a fun hobby, on a whim she applied to Berklee College of Music. They accepted her in 1973, when she was 16, and that’s when she discovered jazz.

Remler’s dual musical background – she loved Jimi Hendrix as much as she loved Wes Montgomery – gave her playing an unusual character that made her a sought-after musician during her short career. After this prodigy graduated from music school at 18, she moved to New Orleans and introduced herself to jazz guitar master Herb Ellis. He helped her book a gig at the Concord Jazz Festival, and that put her in the big time.

As a guitarist, collaboration was a necessity, and she often worked with the top people in her field. One of her most important associations was with singer Astrud Gilberto, who got her into playing Brazilian music.

As for the infamous sexism of the jazz scene, Remler never let it slow her down. But that’s not to say she didn’t experience it. She once told a reporter that, when she was playing, “I don’t know whether I’m a boy, girl, dog, cat, or whatever.” But once she left the stage, “That’s when people remind me I’m a woman.”

Remler died in 1990, at the age of 32, of a heart attack that probably resulted from drug addiction. A terrible loss and a terrible waste, but the jazz world was lucky to have her as long as it did. She deserves to be remembered. Please enjoy these eight great tracks by Emily Remler.

- “Perk’s Blues”

Firefly

Concord

1981

Remler’s debut album contains a wide range of tunes, from Ellington to Jobim, and a few by Remler herself. She signed with Concord when she was 22, and her first record was produced by the label’s founder, Carl Jefferson; Concord Records had originally specialized in jazz guitarists, so it’s not surprising that Jefferson was happy to corral another one and work with her personally.

“Perk’s Blues” is one of Remler’s own tunes. You can hear why she was so valued for her ability to swing effortlessly while playing virtuosically. And she’s joined by some top-notch swing men: Hank Jones on piano, Bob Maize on bass, and Jake Hanna on drums.

- “Cannonball”

Take Two

Concord

1982

For her second album, Concord experimented with calling Remler and colleagues the Emily Remler Quartet. This time it’s James Williams, piano, Terry Clarke, drums, and Don Thompson, bass.

The album opens with the 1955 tune “Cannonball,” by alto sax legend Cannonball Adderley (who had died in 1975). Thompson’s frenetic rhythm on the drums is spectacular, helping to drive Remler’s light-fingered bop.

- “Nunca Mais”

Transitions

Concord

1983

Once again the guitarist is billed just as Emily Remler, and she’s working with yet another group of colleagues (this time with the trumpet of John D’Earth instead of a pianist). Transitions is a good example of the Gilberto influence on Remler’s taste and style.

This track is a very fast version of a samba by Antonio Carlos Jobim, usually called “Brigas, Nunca Mais.” Remler shortens the title, which seems appropriate, given her breathless tempo. By using techniques like not pressing all the way down at the frets, Remler turns her guitar into a percussion instrument.

- “Catwalk”

Catwalk

Concord

1985

Remler wrote all seven tracks of the Catwalk album. All the same folks are back in the studio as the previous album, including John D’Earth and his mesmerizing trumpet playing.

“Gwendolyn” starts at 11:56 on this full-album video (ignore the incorrect time links in the video caption). It’s great to hear Remler play something so lyrical. Bob Moses’ work on the brushes is particularly noteworthy.

- “Six Beats, Six Strings”

Together (with Larry Coryell)

Concord

1985

Larry Coryell, who died in 2017, was sometimes known as the “Godfather of Fusion,” which made him the perfect partner to the multi-genre Remler. Here, it’s just the two guitarists trying to get inside each other’s head on this intense but fun album.

The Coryell composition “Six Beats, Six Strings” uses Spanish fingerpicking patterns and blends them into cool jazz harmonies. What a treat to hear these masters play acoustic instruments!

- “The Second Time Around”

Rosemary Clooney Sings the Music of Jimmy Van Heusen

Concord

1986

Rosemary Clooney is one of those rare Hollywood stars who matured into a great musician. The lower and older her voice got, the more sophisticated her performances, and she wound up being a surprisingly effective interpreter of jazz standards. Clooney was 58 when she made this album, yet she was clearly keeping up with the times, choosing young Remler to join her array of backing musicians.

“The Second Time Around” features a very mellow Remler, providing perfect support for Clooney’s understated expression of Sammy Cahn’s famous lyrics.

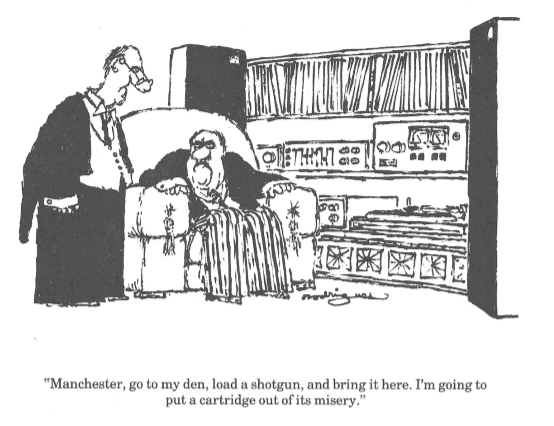

- “Daahoud”

East to Wes

Concord

1988

The Remler Quartet has another incarnation. The only surprise is that it took Remler so long to make an album in honor of one of her guitar heroes, Wes Montgomery (1923-1968). But a closer look at the track list shows that this is a more general tribute, acknowledging several of her favorite musicians.

One of those is trumpeter Clifford Brown. There’s no trumpet on this record, so Remler has to take the lead on Brown’s “Daahoud.” As she explained on the jacket notes, “I really identify with the trumpet. A guitarist can sound like a trumpet player. I try sometimes.”

- “Around the Bend”

This Is Me

Justice

1990

For her last album, Remler embarked on what she presumably meant to be a new chapter in her musical life: a blending of contemporary and jazz sounds. To this end, she amassed a large component of session musicians to help out on This Is Me.

“Around the Bend” is a Remler composition. The soft-jazz harmonies and reverberating hi-hat are telltale signs of the “contemporary” genre that the music industry was pushing hard around 1990. But Remler’s playing is transparently expressive without over-reaching.

NRBQ

In 1966 two kids who were not being watched carefully started a garage band in their hometown of Shively, KY. Terry Adams played keys and sang, brother Donn played horns and percussion. The brothers recruited a buddy on drums and recorded some home tapes, on one of which Donn announces “Here they are, the New Rhythm and Blues Quintet!” despite the fact there were only three guys there. Here’s a moment that starts the band name and the sense of humor that would define the band and their stage persona for the next 50 years.

Terry and the band moved to Florida in 1966, and in 1967 some members returned to Kentucky but Terry stayed in Florida joining the band Seven of Us which included Joey Spaminato from the Bronx on bass. Bands crap out. It happens. So by the spring of ’67, kicking off the Summer of Love, the band was Terry Adams on keys and vocals, Joey Spaminato on bass and sweet vocals, Tommy ‘Rock-A-Baby’ Staley on drums, Frank Gadler on vocals, and Steve Ferguson on guitar. It wasn’t the seven of anything. It was the NRBQ.

The band worked with Eddie Kramer (!!!) at the Record Plant near the end of 1968 and was signed to a two record deal with Columbia. Their first album NRBQ was released in 1969 and in 1970 they worked with Carl Perkins on their Boppin the Blues album. These guys were quickly and clearly on their way during one of the most prolific periods in rock history. Right.

By the third album changes were made, one epic and the other typical of the rest of their career. ‘Big Al’ Anderson from The Wildweeds (Featured in Copper #92) replaced Steve Ferguson on guitar to begin a 22-year journey with great music and even greater live performances. The other change was they switched record companies to Kama Sutra and recorded their third LP, Scraps. Please. If you take nothing else away from this article get a copy of Scraps. I believe this was their greatest work, a classic in itself with at least three songs that will thrill your heart/libido/first car memory.

I’ve been listening to a lot of NRBQ music to prepare for this column and there are greats out there, each album with at least one song capable of a national hit. Love the fifth album NRBQ at Yankee Stadium. From the title you’d assume they played Yankee Stadium but instead the title is literal. The boys had gone on a tour of the iconic venue and had their picture taken there. See There they are. Right there. Squint a little. They’re sitting in the dugout…I think.

Just after Scraps Tom Ardolino replaced Staley on drums and the band was set until 1994. In the ’70s my wife and I used to see NRBQ at the Shaboo Inn which raised hell situated between UConn and Eastern Connecticut State in Willimantic. When the Q were there, you went. Period.

Every studio album showcases the humor and out-and-out wackiness of these guys. But live they were just SO much damn fun. Here from the eighth album TiddlyWinks, “It Was An Accident”.

And from the same show “That’s Neat, That’s Nice”.

Man those voices complement each other like cheeseburgers and fries. BTW, those are the Whole Wheat Horns that joined these nuts often.

This version of NRBQ sported three live albums. I don’t know Honest Dollar, but God Bless Us All and Diggin Uncle Q are gems. Here is “Daddy Loves Mommy-O Who Does Daddy-O Love”. Bout a couple that goes out on the town separately and find each other in a club.

As wacky as they were each album had at least one beauty of a love song on it. This is a live version of “You’re So Beautiful”. Sweet arrangement with nice solo work and singing from Al.

The dipshit record companies seriously whiffed on these guys. Thank the Lord they don’t run things anymore. No one seemed to know what to do with this obviously talented group of musicians and songwriters. Audiences adored them and the critics loved them but the record companies could not get a handle on NRBQ. After the first two albums with Columbia came two albums with Kama Sutra. Then one with Red Rooster, one with Mercury and two with Red Rooster/Rounder. Followed by one with Bearsville, three more with Red Rooster Rounder, one with Virgin and one with Rhino. This last Message from the Mess Age in 1994 was Big Al’s last gasp with the band. He moved back to Windsor, CT for a few years where he lived around the corner from my brother Ed. Al Anderson eventually moved to Nashville where his song writing talents were finally appreciated, writing hits for folks like Vince Gill, Alabama, Jimmy Buffett, Carlene Carter, George Strait, and Trisha Yearwood, including a number 1 with Tim McGraw.

This is a vid from the Dennis Miller Show where Miller screws up the intro and the band performs the lead song from their last album together, Message From The Mess Age.

A fitting allegory for how the record companies never knew what they had and despite that the band kills.

In 2014 Vince Gill listed his 14 favorite guitarists for Rolling Stone. He had Big Al on the list with guys like Jimmy Page, Sonny Landreth, Chet Atkins, Joe Walsh, and Derek Trucks. Nuff said.

I left this column a little short because I really wanted to include a lot of music. I hope you are enjoying this dance with me. Had a great time jumpin’ in my seat. From a TV show in 1980 “Rocket in My Pocket”, Al in a tux for some reason. Probably came right from court.

You see an example there of the gas lighting style of Terry Adams on the keys. But what you picked up live and on their albums, Adams was a helluva piano player. On this cut the guys pull out Thelonious Monk and end rocking.

“Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”. Sorry Gordon. Hahahaha!

In the late ’80s there was this show called Saturday Night with Connie Chung. I got a call from a CT buddy yelling that NRBQ were on TV. Let’s end with that. Thanks for sticking with me. NRBQ was a GREAT Rock and Roll band, and a great act.

OK, OK I’m getting requests for another tune. This is one of my favorite love songs of all time and a beloved Q tune. From Scraps, “Magnet”. Big Al’s sweet little licks all through the song and Terry on the piano.

Shiver me timbers.

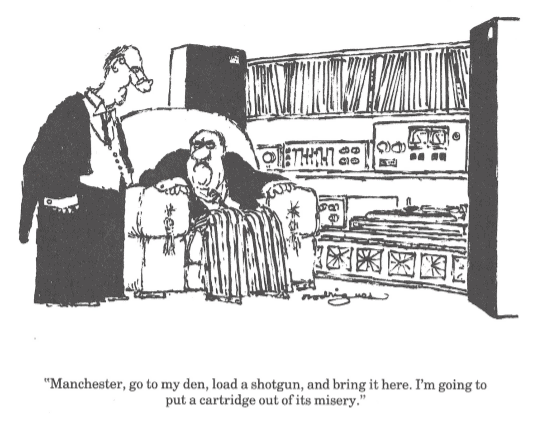

How Records are Made, Part 2: Plating and Pressing

The disk mastering stage, discussed in detail in the previous issue, was the last stage permitting intentional changes to the sound of the final product, for aesthetic or technical reasons. While plating and pressing can and often do have a dramatic effect on the sound of a record, this is always unwelcome and unintentional.

Ideally, the recording would be an identical representation of the acoustic reality, the transfer to the master disk would be an identical transfer of the recording and the plating and pressing process would yield vinyl records containing grooves identical to those on the master disk, with nothing added and nothing removed. The reproducing system would then translate these grooves back into the original acoustic reality, right there in your living room. Reality, however, always interrupts us before we reach this ultimate nirvana.

Microphones, loudspeakers, cutter heads, cartridges, magnetic tape heads, electronics, and all other components of recording and reproducing systems are still far from perfect. They do, however, allow a subjective element, which may compensate to some extent for the inability of the technology to really capture and subsequently reproduce the exact original acoustic reality in a different space at a later time, through the selection of the most appropriate microphones, their placement, pairing with certain electronics, adjusting controls, and so on. Likewise, the selection of loudspeakers, their placement in the room, choice of electronics, cables and other accessories, introduces a subjective element, which will best serve to create the illusion that even if this is not the original acoustic reality, it is getting impressively close to it.

In plating and pressing however, we are dealing with industrial mass-manufacturing processes and manufacturing tolerances. It is no longer possible to adjust parameters of the sound in the sense of adding more bass or having any other form of creative control.

The ideal of vinyl records identical to the master disk can never be achieved due to the inevitable manufacturing errors. Each plating and pressing facility needs to be set up with a certain target for manufacturing tolerances and keep their process parameters under control to repeatably and reliably turn out products that fall within these tolerances.

Working to extremely tight tolerances means that the product is more consistent, accurate, and truer to the master disk. In such cases, the errors can be kept so small as to be practically below the threshold of perception, resulting in a product that is, both subjectively and even objectively (via measurements), extremely satisfactory.

However, tight tolerances require tight process parameter control, more elaborate equipment and facilities, a more skilled workforce, better raw materials and inevitably, a higher rejection ratio. This last point is often not properly appreciated. Even the finest facilities will produce records that are out of spec. When they do, they will usually quickly realize and make the necessary adjustments to bring things back to normal. However, there are still some out of spec records there and a choice to be made: “Are these to be sold to the customer along with the good ones, hoping nobody will realize, or are they to be destroyed?” This question can be rephrased as follows: “Who pays for these out-of-spec records, the customer directly, or the customer indirectly?”

In the end, the pressing plant is there to serve the demand for a certain product. It is the customer who needs the product and pays for whatever it takes to manufacture it to their standards. If their standards are high and to have 1500 records of acceptable quality, a total of 1000 records must be manufactured, 500 of which must be rejected for failing to meet these high standards, then the customer should be prepared to pay for 1500 records, the high quality raw materials, the more elaborate parameter control, and the skilled individuals who can make this happen. They will either pay this upfront, by choosing a better (and more expensive) pressing plant who will be honest about what is needed, or they can choose to pay less for a plant that will deliver inferior records, reject, then pay more to have more pressed, reject some more, pay some more, and so on. At this point in their learning curve, many record labels decide to just sell the inferior records and not care about it, if they believe their customer base will accept this.

Some people prefer to waste their money in small increments. Others invest it more wisely in larger chunks. The exact same applies to the consumer. If you really do want excellent records, you will have to be willing to pay for what it takes to make them. Neither the record label (or artist who self-releases), nor the pressing plant, mastering facility, or recording studio will absorb the increased cost of higher quality. If the consumers are not willing to pay for higher quality, nobody will.

But let us leave the economics aside and see what happens after the master disks have been cut.

Master disks are soft, fragile, and contain microscopic grooves of nano-scale detail. We need a way to replicate this groove structure accurately on multiple vinyl records. The general concept is that we need to first make a durable “negative” of the master disk, containing ridges instead of grooves, and then use it to “stamp” this structure as grooves on plastic records. Unlike the rubber stamps we use with ink on paper, record grooves are 3-dimensional and the geometry is critical.

To further augment this piece with the latest trendy keywords, the “negative” is made using an additive manufacturing process frequently associated with nanotechnology: Electroplating! (And has been done this way for over a century!)

But first, the master lacquer disks must be visually inspected for defects and then be thoroughly cleaned and chemically treated.

Then they are sprayed with silver nitrate to give them a thin conductive coating. This step is called “silvering”.

The silvered master disks are then immersed in a galvanic bath where they are plated with nickel. This is a very tricky process. The nickel negative is slowly “grown” through electrodeposition. The bath temperature and rate of deposition are critical parameters for accurate plating. Getting these wrong can ruin the master disk and/or the negative. Doing it too fast introduces stresses and defects. Doing it too slow increases the cost and lowers productivity.

Photograph courtesy of Magnetic Fidelity.

When the negative has been grown, it needs to be carefully separated from the master disk. The master disk, at this point, has fulfilled its goal in life, and with surface damage from the separation of the nickel negative, can no longer be used. The negative could now be used directly to press records, but it would only be able to press around 1000-1500 records at best, before it gets worn out. No longer having the master disk available, this would be too risky and uneconomical. Instead, we usually call this negative a “father”, clean it, chemically treat it and dunk it in a galvanic bath to plate it. A nickel positive is grown on it, this time having grooves on it. This is separated from the “father” and we call it a “mother”! The mother can be inspected under a microscope and it can also be played on a turntable with certain precautions to prevent damage. Anyone who has ever heard a metal mother is left wishing we could just make 1000 metal mothers instead of vinyl records! In fact, we can, but be prepared for a 4-figure retail price. But, less friction between groove and stylus and no deformation distortions translate to improved transients, HF response, and lower distortion. However, nickel is ferromagnetic, so we would be limited to moving magnet and moving iron cartridges. I do have ideas about this, but they would be dismissed as rabidly uneconomical by any MBA with even the slightest desire to fit in with the mainstream…!

Photograph courtesy of Magnetic Fidelity.

Photograph courtesy of Magnetic Fidelity.

Photograph courtesy of Magnetic Fidelity.

So, the mothers get cleaned, chemically treated and sometimes even dehorned, deticked, and polished, before being placed back into a galvanic bath to grow another negative, which we call a “son” or “stamper”. A mother can grow several “sons”, since she is tough and resistant to separation damage (as long as the person doing the separation actually knows how to do it). Happy family moments!

Photograph courtesy of Magnetic Fidelity.

Stampers then need the be accurately centered. This is what defines the centering of a record. The centering is done by observing the run-out on the locked groove under a measurement microscope and adjusting a turntable stage until it is deemed acceptably centered. At that point, a center hole is punched, but not a small one for a turntable spindle! The stamper is held on the molds of a press, through a larger center hole and around the perimeter.

Photograph courtesy of Magnetic Fidelity.

The stamper is sanded on the back and label area and “formed” on a “preformer”, giving it the necessary contour around the edge and center for the mounting hardware on the press.

Photograph courtesy of Magnetic Fidelity.

Two stampers are fitted on a press, one for each side of the record. Raw PVC is formed into soft “pucks”, often called “biscuits”, through an extruder. A puck is sandwiched between two round paper labels (already printed and dried in an oven) and inserted into the press, between the two stampers. Steam heats up the molds and a hydraulic system presses the puck into a flat record with the grooves stamped on it. Then the steam is shut off and water runs through the molds to cool them and solidify the record.

PVC is a thermoplastic, so it softens with heat and hardens again when cooled. At the end of the cooling cycle, the press opens, the record is removed and is moved to the trimmer table, a turntable which clamps and rotates the record while the edge is trimmed. After the edge trimming, the records are stacked on cooling plates and left there to fully cool down and stabilize, sometimes for over 24 hours.

SMT Record Press

The timing of the steam and water cycle, the pressing force, the hydraulic system and steam pressure, the extruder settings and the puck temperature are all critical. Improper compression molding parameters result in noisy records with high distortion, warps, and many other defects. In particularly bad cases, the result can even be damaged stampers and molds, or toxic fumes from overheated PVC. Rough edges can result from bad trimming, dents can appear on the record surface as a result of worn molds or stamper mishandling, while inadequate time on the cooling plates results in warped records.

The first few records are considered “test pressings” and are sent to those involved in the production of the record for evaluation and approval, before the proper manufacturing run commences. Usually, this evaluation is done on accurately calibrated reproducing systems, by the producer, record label executives, mastering engineer (for a technical perspective), and occasionally also the artists themselves. This is the first opportunity these people have of actually listening to what has collectively been achieved in disk mastering, plating, and pressing. If any problems are found, they have to be traced back to their source and rectified. In case the fault occurred prior to the mothers, the entire process has to start all over again, with cutting new master disks. When planning a high-quality release, an adequate budget must be set aside to cover the event of unforeseen problems. It could be that masters will need to be cut more than once, if need be, to maintain the desired level of quality, along with additional plating runs and more test pressings.

Once the test pressings are approved, the manufacturing of the final product can start. It could range from a few hundred to a few thousand copies. For international hit albums, selling millions of copies, stampers are sent out to pressing plants in many different countries. Then comes the real challenge: Quality Control of thousands of records, within a reasonable time frame and budget! We shall discuss this topic in the next episode!

SMT Record Press

[Header image courtesy of Magnetic Fidelity.]

The Killers

Until the Killers came on the scene, the phrase “Las Vegas music” tended to conjure up images of late-career crooners in casino supper clubs. But in 2001, when singer and keyboardist Brandon Flowers and guitarist David Keuning got together to share their love of New Wave, post-punk, and rock, Vegas got a distinctive new sound.

Something else that sets this band apart is its shunning of certain industry conventions. Output, for example. In 18 years, the Killers have released only five studio albums. All five have sold very well – in fact, every album has hit No. 1 on the UK charts; they’re the only non-British band to accomplish such a feat – proving that their own pace is the right pace.

They’ve also made a very unusual decision with regard to personnel. The original four still write the songs and record the albums, but only two of the originals still go out on tour. On the road, they fill out the ranks with other musicians instead. Not many bands would have the emotional maturity to make that arrangement work.

By 2002, bassist Mark Stoermer, and drummer Ronnie Vannucci, Jr. had joined Keuning and Flowers. They signed with British indie label Lizard King and with Island Records for American distribution. Their debut, Hot Fuss (2004), came out at a healthy No. 7 in the US and even higher in the UK, producing four big singles before being nominated for a Grammy for Best Rock Album. The Killers had arrived.

On “Midnight Show,” Flowers and Keuning collaborate perfectly – the long-noted, melody in a limited range, contrasted against the meandering and frantic guitar. The breathless organ chords at the end put a bow on the emotional display.

One of the bonus tracks on Hot Fuss is proof enough that the band members were hoping to move beyond niche. “Glamorous Indie Rock and Roll” is a sardonic dig at the twee independent rock scene.

One reason Flowers was fired from his previous band, Blush Response, was his impatience with doing synth-pop, to the exclusion of rock and roll. The second Killers album, Sam’s Town (2006), addresses this need, and is often noted for its heavy Springsteen influence.

A more complex production than first album, this time there are many additional musicians, under the eye of British post-punk producer Flood.

“This River Is Wild,” composed by Flowers and Stoermer, has a rich texture, almost like a Phil Spector track. The lyrics, though, deal with life’s nitty gritty, like something by The Boss.

From these same sessions comes “Peace of Mind.” It wasn’t included on the album at first, but showed up on the 10th Anniversary LP edition. The quietly screaming obbligato of Keuning’s guitar is quite haunting.

For their third album, Day & Age (2008), the band made the somewhat surprising choice of hiring Stuart Price, famed for producing records for Madonna and Take That. Price’s pop sensibilities helped make the single “Humans” into the Killers’ most recognized song.

The session personnel list is greatly scaled back from the Sam’s Town cast of thousands, bringing the focus back to the quartet itself. “It might not be as masculine as Sam’s Town,” Flowers once said about this scaled-down sound. Which is not to say this is a quiet album, just a bit more laid back, as you can hear in the almost Hawaiian sway of “Neon Tiger”:

This may be why “A Crippling Blow” was saved as a bonus track from UK/Ireland release. It’s as rhythmically strident as something from INXS. The lyrics seem to deal with isolation and the constant mild panic of getting through life.

For all the success they’d had up to this point, Battle Born (2012) achieved the strongest US chart position, rising to No. 3. The album had taken its time in coming. After Day & Age, everyone was tired of each other, and three of the four band members were itching to work on other projects. So, they took more than a year apart, returning to the studio in 2011.

A whole host of producers contributed to the recording sessions, among them Stuart Price again, plus another revered veteran of British rock, Steve Lillywhite. Lillywhite produced several of the songs, including the title track. The phrase “Battle Born” appears on the Nevada state flag, and the song is generally interpreted as a lament on the state of America.

Damian Taylor was the producer for the ’80s retro sound of “Deadline and Commitments,” quite a contrast from the violin arrangements on “Battle Born.” This song emphasizes Flowers’ floating upper register against the bare sound of bass guitar and lower-pitched drums. The overdubbed backing vocals of Flowers singing with himself couldn’t be more different from the big sound of the Las Vegas Master Chorale on the Lillywhite track.

The band’s most recent album is Wonderful Wonderful (2017). And it was their first US No. 1 album. Just before recording started, bassist Stoermer decided that, while he was willing to keep recording, he’d had it with touring. Guitarist Keuning made a similar decision the following year. So, if you see The Killers live, you’ll probably see Flowers and Vannucci, plus some special hires. In the past couple of years, those guests have included Jake Blanton on bass and Ted Sabley and Taylor Milne on guitar. An unusual arrangement, but it seems to work.

Speaking of guest guitarists, Mark Knopfler makes a special appearance on Wonderful Wonderful, bringing an earthy motion to the meditative “Have All the Songs Been Written?”

It’s only been two years since Wonderful Wonderful came out, which is a standard breath in Killers time. And there have been other signs of studio life. In January 2019 they released a single called “Land of the Free.” For those who doubt that “Battle Born” bemoans America’s current condition, there’s no mystery here. The official video, directed by Spike Lee and featuring footage of asylum-seekers at the southern border, makes it clear that “Land of the Free” is a darkly ironic title.

Muggings

It was the jostling that alerted me. I looked down and saw a hand removing money from my pocket.

This was almost identical to an incident that had happened to me years before in New York when I had a loudspeaker factory in Manhattan. I was traveling to work on the E train one morning and I noticed three young black men around 15 or 16 sitting opposite me. What was novel about them was their manner of dress. Each had on the same red sneakers, red jackets, red baseball hats and baggy pants. They were talking quietly among themselves and apart from their uniforms there was nothing remarkable about them.

As the train approached the Houston St. station, I rose and moved over to the exit. Just before it stopped, I felt someone pushing on my back and someone else crowding me on my left side. I looked down and saw a hand pulling money from my right pocket. Instinctively, I splayed both arms sideways. At this time I was building speakers mostly by hand and I had strong muscles in both arms. I made contact with two of the boys with such force that both went flying down the center of the train. Fortunately the one on my right dropped my money and all three of them fled as the doors opened. I retrieved my funds, walked off the train and noticed two policemen standing at the other end of the platform, one was white, the other black. I approached them and told them of the incident. They asked me to describe the boys.

“They were three young black kids and they all looked alike.” I meant of course that their dress was identical, but was too rattled to speak clearly. The black officer looked at me in disgust and walked away.

Barcelona is my favorite city after Paris. The town is dripping with culture (see some of Gaudi’s architecture) and never fails to titillate my artistic and culinary desires. It is a delightful city for walking and a favorite pastime of my wife and I, is to amble randomly around town. On a trip around 2009, we set off to climb Montjuïc, a hill that dominates part of the skyline. We walked at random, using sightings of the hill as a reference. This is a delightfully pleasant way to explore a town. (I’ve done the same in Paris using the Sacre Coeur Basilica as a geographic reference). The walk was somewhat more arduous than expected, and we arrived wearier and hotter than expected.

Montjuïc Hill houses the Miro foundation (well worth the visit) and among other venues, the Museum of Catalan Art and the Ethnological Museum. After an afternoon exploring Spanish culture especially the large exhibit about Barcelona’s “Roma” population, my wife, daughter and myself decided to take the subway back to the center of town where we had rented an apartment.

As I was buying tickets from the machine, I again experienced the jostling I had felt years ago in New York. Once more a hand was extracting bills from my pocket. I belted the kid with my fist and as he fell down, I saw him put my money in his pocket. He scrambled up to flee but I grabbed him, put my hand in his pocket, seized my money and shoved him away. He and his other 2 friends scarpered and disappeared in seconds. My wife was looking on with horror, as she had no idea how violent I could be. On the other hand, my daughter was gazing at me with renewed appreciation of her dad. Back in the apartment, I counted my money and was delighted to find that I had taken a large wad of extra money from the kid’s pocket. In fact, it was around 200 Euros. The irony of this brought a smile to my lips.

From Wallkill to Bethel

When last we met, I put forth my guess as to one of two reasons Woodstock, despite being the largest music and art festival ever, was also the most peaceful. The first was the inspired choice for a security “force”. This is the second part.

The festival was originally slated for a flat piece of ground that was intended to become an industrial park. It was ideal for a smaller event, if a bit boring. Were the festival held there, it probably would have ended up like a number of events held at racetracks, like the Miami and Atlantic City Pop Festivals.

The land was leased; work was proceeding on construction and fencing. But fate intervened. Some local people didn’t like the thought of the rumored 50,000 attendees descending on their town. In early July, Wallkill passed a local ordinance requiring permits for any events with more than 5,000 in attendance. And then in mid-July the event was banned altogether over the use of portable toilets.

So — in reality, over 150,000 tickets had been sold to an event that now had nowhere to take place. I imagine the promoters were truly panicked. By the time an alternative site was found — the Yasgur dairy farm in Bethel, NY — there wasn’t enough time to do the preparation needed.

On the Monday preceding the start of the festival (which was coming right up, on Friday), a meeting was held and the construction foreman told the promoters the news: a choice had to be made between completing fencing the festival site in or completing the stage. There wasn’t enough manpower or material to do both. Reasoning that if they went with the stage, they’d be bankrupt, but if they went with the fencing they’d all go to jail, they chose completing the stage.

From such decisions a generation’s fate is decided. The festival was now free.

“That doesn’t mean that anything goes, what that means is that we’re going to put the music up here for free. What it means is that the people who are backing this thing, who put up the money for it are going to take a bath; a big bath. That’s no hype, that’s truth — they’re going to get hurt. But what it means is that these people have it in their heads that your welfare is a hell of a lot more important, and the music is, than a dollar.” – John Morris, from the stage.

Attended by nearly half-a-million well-meaning souls with good intentions, un-policed except by the Hog Farm (see Part I last ish), it was free to meander through music, mud, rain, skinny-dipping, traffic jams, food crises, acid trips both good and bad, broken bones and births (and two deaths), and a generally good time was had by most.

Incidentally, the food crises gave rise to another virtue of Woodstock. It wasn’t that the promoters were unprepared, it was the traffic jam resulted in people just abandoning their cars — and at a certain point the food couldn’t get in. In the end, the Hog Farm provided some and the people of Bethel provided what they could. As Wavy Gravy so famously put it, “We’re all feeding each other…”

Standard Time

It may seem like I seldom devote space here to repertoire favorites, e.g., Top Twenty World’s Greatest Concertos.

Why is that?

Well, some people are heavily invested in the Top Twenty thing, and they make it work. I’m not, and I don’t. Over the years, I’ve tried to emphasize new “serious” music, and whenever possible, I opt to consider new releases independently of back-catalog competition. My guiding principle is, you can’t stick your toe in the same river twice. Artists change, audiences change, cultures change. The notes on the page may stay the same, but we don’t. Bring on the new, whether it’s tunes or those who whistle ‘em.

This week, though, it’s mix-and-match: new releases of familiar music by Tchaikovsky, Strauss, Mendelssohn, and others. Nothing obscure! No “forgotten gems”! Genuine repertoire favorites! I’ll even make a few comparisons.

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 6 in B Minor (“Pathétique”). [1] Berliner Philharmoniker, Kirill Petrenko. BPHR, 2019; SACD, downloads. [2] MusicAeterna, Teodor Currentzis. Sony, 2017; CD, downloads.

The Berlin Philharmonic is celebrating its appointment of new music director Kirill Petrenko by releasing a live concert recording of the “Pathétique,” which comes in a deluxe 36-page hardbound edition housing a hybrid SACD and passcodes for hi-res audio files, plus notes on the music and on Petrenko’s ascension to the throne. It must be meant as a keepsake, because the book measures 6⅛” x 9⅝”, so you can’t easily shelve it with LPs or CDs.

I didn’t originally intend to review this alongside Teodor Currentzis’s 2017 release for Sony. But having listened to both, I could not resist. Petrenko’s interpretation flies in the face of a decades-long series of “Pathétique” recordings that emphasized heart-wrenching autobiographical drama, often in such stark terms that one could imagine listeners left barely able to form words or choke down a little soup. Each new recording in that mold was hailed with superlatives: it was “breathtaking,” a “Sixth for our time,” and so on.

Now here is a reading that brings out the lyricism and delicacy of Tchaikovsky’s creation in at least equal measure. It remains absolute music at all times, never veering into Hitchcock territory or touching on any of Dante’s circles of hell. As usual, the Berliners bring considerable technical skill and sensitivity to the task. The recorded sound is spacious, detailed, and well-balanced. It’s a virtual MRI of the score, as befits this suave, utterly refined presentation.

The problem? In strictly emotional terms, Tchaikovsky’s Sixth takes no prisoners. Either you bring that sensibility to the task and shape your performance accordingly, or you risk ending up with . . . Mantovani. Or Samuel Beckett, which oddly enough was the taste I found in my mouth: on first hearing, it seemed that Petrenko offered the final movement as a corpse already drained of blood. I kept waiting for the music to begin, whereas existentially it was already over.

That approach can be effective. There’s a case to be made for the fourth movement as exhaustion, as the collapse that follows a burst of false hope. Yet when I listened to what Currentzis and his intrepid band had wrought, I had to reconsider. They give us the finale as a primal cry, despairing but determined to be heard. It’s profoundly human, and the sound of it sears your brain. So let’s talk about that sound for a moment.

Although Sony’s engineering for Currentzis is both impactful and transparent, it’s biased toward impact: this is no MRI. I found myself actually repelled by one passage in the last movement: a low [written] C# in the horns that enters repeatedly toward the end of the work. Marked ff and “gestopft” (“stopped,” a hand position that can produce a nasal, compressed sound), it’s prominent in Currentzis’ recording but can barely be heard in Petrenko’s. This sound, along with some aggressive string entrances, certainly contributes to the pathos in the performance. (I suspect its power also derives from the adroit manipulation of sliders in the control room. Writing for Gramophone, Peter Quantrill detected other studio tricks.)

Did Tchaikovsky want the note to sound that ugly? We can be sure he wanted it heard. The composer introduces it as an accompaniment motive in the woodwinds in m.2, then transfers it to horns 90 measures in, when the principal theme is recapitulated. Returning again, as the coda gets underway, it’s lower, darker, and much more acidic in tone; you could say it carries a depth charge.

My experience with Currentzis’ stopped horns forced me to revisit Petrenko, and that led to greater respect for Petrenko’s achievement. Maybe he’s the revolutionary here, offering a gentler means of understanding the “Pathétique,” minus the now-customary raw histrionics. I could quibble (obviously) with either performance, but both are exceptional and well worth knowing.

Handel: Concerti grossi, op. 6 (1–6). Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin, Bernard Forck. Pentatone, 2019; SACD, downloads.

George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) spent most of his career in London, writing and presenting opera and oratorio. But he was well-versed in all genres, including orchestral concertos. Opus 6 is unusual only in that Handel wrote these 12 concertos all at once and with relatively little borrowing. He performed them in his 1739–40 oratorio season, during intervals and under his own direction. Musically they follow the example of Corelli, utilizing a cosmopolitan blend of styles, something new at every turn.

This album includes only the first six (coming soon: vol. 2). Here are two excerpts from No. 3, the opening Larghetto and a more lively Polonaise:

Top-notch performances from one of the most respected early-music groups in the world, and top-notch sound from Pentatone, of course.

Holst: The Planets. Elgar: Enigma Variations. Bergen PO, Andrew Litton. BIS, 2019; SACD, downloads.

For me the highlight here is the Elgar Variations, a work I confess to knowing only superficially prior to reviewing Litton’s new release. The Elgar was recorded in June 2013, the Holst in February 2017. Meanwhile the conductor had moved on from his 12-year tenure (2003–15) as Bergen’s music director. Litton is now “emeritus” or “laureate” conductor of several orchestras, including those of Bournemouth, Dallas, Bergen, and Colorado. On the evidence of his recordings, he’s an A-list conductor, in spite of his never having helmed an A-list band.

Each variation is dedicated to one of Elgar’s friends; at the heart of the Enigma lies “Nimrod,” offered below in its entirety. Here, let’s sample a bit of Variation 11. It’s a snapshot of Dan, the bulldog that belonged to George Robertson Sinclair, organist at Hereford Cathedral:

And now some of Variation 13: Elgar indicated with asterisks “the name of a lady. . .on a sea voyage,” bound for Australia. Elsewhere he described the dedicatee, Lady Mary Lygon, as “a most angelic person.”

Nicely captured by producer Ingo Petry and his engineers. Useful liner notes by Philip Borg-Wheeler too, although he asserts that “Musical representations of personal friends are uncommon.” They are not, but they seldom turn out as well as Elgar’s did.

Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique; Fantaisie sur la Tempête de Shakespeare. [1] Toronto SO, Toronto Mendelssohn Choir, Sir Andrew Davis. Chandos, 2019; SACD, downloads. [2] Swedish Radio SO, Daniel Harding. Harmonia Mundi, 2016; CD, downloads. [w/ Rameau, Suite de Hippolyte et Aricie]

Tastiest morsel in Davis’s feast is not the Symphonie but the 15-minute Fantaisie, presumably intended as a lively curtain-raiser. It steals the show, given Sir Andrew’s pedestrian traversal of the main course. He seldom finds the pulse of the larger work, which depicts a young man’s feverish, drug-addled fixation on a woman. Here is the moment when music representing that idée fixe first appears:

And here is the same moment from my favorite recent recording—Daniel Harding’s, for Harmonia Mundi:

Harding delivers the twitchy, deeply neurotic goods; Davis comes off as sturdy and dependable.

Strauss: Also sprach Zarathustra; Ein Heldenleben. Oslo PO, Vasily Petrenko. Lawo, 2019; CD, downloads.

As with Berlioz’s Symphonie, of the making of new Strauss albums there is no end. (Anyone interested in a short stack of misguided Alpensinfonien?) Yet, even when I compared these Oslo performances with classic Chicago (Reiner) and Berlin (Karajan) recordings, I still liked them. Vasily Petrenko—late of Liverpool, and no relation to Kirill—has been up to excellent things in Norway. His interpretations are dynamic in the best sense: each phrase, period, and section contributes to interlocking structures that ration out, then ratchet up the intensity. Arrival points register firmly but in a way that heightens the momentum. That’s exciting. Here’s some of Heldenleben:

These are way more fun than what’s currently on offer from Søndergård or Jurowski.

Mendelssohn: Overtures. (“Mendelssohn in Birmingham, vol. 5”) City of Birmingham SO, Edward Gardner. Chandos, 2019; SACD, downloads.

Some of these overtures appeared as filler in vols. 1–4 of Gardner’s “Mendelssohn in Birmingham” series, but it was a neat idea to repackage them this way. Old favorites like The Hebrides and Ein Sommernachtstraum roost comfortably beside relatively rarities like the “Trumpet” Overture and Overture to “Athalie.” Here’s the opening of Die schöne Melusine:

Recognize those lovely rising arpeggio figures? They depict the water sprite Melusine frolicking in her element. Wagner stole that music for the opening of Das Rheingold. (In his tribute to Lady Mary Lygon, Elgar committed more gentlemanly theft by quoting from another Mendelssohn overture, Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt.) We close with a bit of the Overture to “Paulus,” which references an old hymn tune as an indirect homage to Bach:

All of which bring up issue(s) of borrowing, adapting, stealing, and quoting, which we’ll survey next time. Happy listening, folks.

Drive, He Said Part 2

In Part 1, Copper #92, we looked at idler-wheel turntable mechanisms. In this article, we’ll look at belt-drive turntables.

The original Edison phonographs—cylinder players, not disc players—were belt-driven. Oddly, the first belt-drive turntable I’ve found didn’t come out until after WWII. Until that point, tables were either idler-wheel or one form or another of direct drive. Undoubtedly there were obscure, oddball exceptions, but I have yet to discover them.

em.The Dutch electronics giant Philips started its own record company around 1950, producing LPs. The company’s first turntable that would play LPs was the 2-speed HX301a. Like the Thorens TD-124, the drive combined an idler and belt-drive—but it did it in a completely different fashion from the Thorens. The TD-124 had a belt connecting the motor and a stepped pulley which drove the idler wheel, which then drove the platter.

On the Philips table, 78 rpm was produced by the motor driving one of two rotating drums with fixed anchor points. 33 1/3 rpm was produced by sliding the motor over to contact the idler wheel, effectively reducing the speed. Unlike later belt-drive turntables, the Philips unit only drove a segment of the platter with the belt; every other design I’ve ever seen wraps the belt completely around the platter.

The first US-made belt-drive turntable was made by Components Corporation. Billed as a “professional turntable”, it seemed to live up to its billing. As you can see from the 1954 review from High Fidelity, the Components table had a 25-pound platter, driven by a fabric belt. By the way—the author of the review, “R.A.”, was Roy Allison, who went on to be a designer for AR and later ran his own company, Allison Acoustics.

Within the next few years, a lower-priced Components table appeared, smaller, lighter, and no longer billed as “Professional”. The belt-drive Garrard RC-80 record changer appeared, and was made by the thousands if not hundreds of thousands. High Fidelity reviewer J. Gordon Holt (still a few years away from founding Stereophile) took note of the two brands in 1957:

“Belt- driven turntables are becoming increasingly popular.

By its nature the belt minimizes transmission of motor irregularities,

which can show up as hum, flutter, etc. Good

examples of belt -drive are the Garrard RC -8o changer and

the Components Corporation turntable. As for Garrard, the

secret of good performance is to keep the belts clean, replacing

when worn or frayed, and to keep a minimum of very

light oil in all working bearings (but do keep them clean).

The writer has found that changers properly set up are very easy on belts.

Flutter and rumble can be tremendously

reduced in Garrard changers by periodic lubrication of the

main turntable bearing (the center section in which the

spindle fits). From time to time it should be taken apart,

cleaned, oiled, and adjusted for end -play (just a bit – not

too loose or too tight).

“The Components turntable is inherently a fine unit. The

directions for insuring proper operation are unusually complete.

To which might be added the following: for lowest

rumble, keep the belt tension as light as possible, and

centered on the drive pulley. Make sure that the turntable

is absolutely level. If you must lift the unit, or transport it,

make sure that the table is isolated from the lower bearing –

damage here can show up as flutter.—J.G.H.”

In 1958, Fairchild came out with a playback system specifically designed for stereo. The 45-45 Westrex single-groove standard placed more stringent demands upon the rumble characteristics of turntables, and the Fairchild 412 was offered in single-speed, two-speed (33 1/3/45) and four-speed variants, the last utilizing electronic speed control to change speeds. Otherwise, drive was by two belts: one from the motor to an intermediate pulley, the second connecting the pulley to the platter. We covered the 412 in greater detail in the third part of our series on Fairchild.

Fairchild ad in High Fidelity magazine, June, 1958

Fairchild ad in High Fidelity magazine, June, 19581960 saw the launch of the Empire Troubador, mentioned in Part 1 of our series on Empire. A belt-driven 3-speed table with a hefty Pabst hysteresis-synchronous motor and a precision-machined platter and bearing, the Empire table stayed in production with minor tweaks and variations through 1977 or so.

Acoustic Research introduced the AR-XA in 1961, and it is likely the best-known belt-drive turntable of all time, and quite possibly the best-selling, as well. Like the Components Professional, the AR featured a sprung sub-chassis designed to provide a certain level of isolation from acoustic feedback. AR founder Edgar Villchur designed the brutally-simple XA, which led the way to the Thorens TD-125, -150, and -160, as well as the Linn Sondek. Initially priced at $58, the XA was still available in the ‘70s for less than $90, and variants of the table were sold into the ‘90s. Many years, more than 50,000 units of the turntable were sold, and a cottage industry arose for mod kits and ‘tables based upon the XA, the best-known of which were made by George Merrill. George still makes some AR tweak parts today.

The AR XA, featured in a 1960's mail-order catalog.

The AR XA, featured in a 1960's mail-order catalog.Into the '60s, the styling and drive mechanism of the venerable Thorens TD-124 seemed old-fashioned. The combination belt/idler drive was both complicated and expensive to build, and so the TD-150 was introduced in 1965 as a less-expensive model. Featuring square-edged styling, a suspended sub-chassis and a simple belt-drive mechanism, the TD-150 was simple to operate, maintain, and repair. Like the AR, the TD-150 and its offspring TD-160 and many variants were and are favorites for tweakers.

As Thorens moved production from Switzerland to Germany in 1968, the elderly TD-124 was discontinued. Its replacement, the TD-125, was essentially an upmarket TD-150, with bigger, beefier everything, and a fancy-schmancy electronic speed control and strobe. When I became aware of quality audio gear in the late '60s, the manual turntables featured in the US press were the AR XA, Thorens TD-125, and Empire Troubador. The AR was popular with the cost-conscious (thousands were sold to college students and professors), the TD-125 was the choice of wealthier enthusiasts, and the Empire was a perennial favorite of features in Playboy and Esquire. In the early '70s, the ultimate set-up was a TD-125 with a Rabco SL-8E linear-tracking arm, often used with a Shure V15 cartridge. Let's just say that over the years since, the TD-125 has held up better than the Rabco.

As Thorens moved production from Switzerland to Germany in 1968, the elderly TD-124 was discontinued. Its replacement, the TD-125, was essentially an upmarket TD-150, with bigger, beefier everything, and a fancy-schmancy electronic speed control and strobe. When I became aware of quality audio gear in the late '60s, the manual turntables featured in the US press were the AR XA, Thorens TD-125, and Empire Troubador. The AR was popular with the cost-conscious (thousands were sold to college students and professors), the TD-125 was the choice of wealthier enthusiasts, and the Empire was a perennial favorite of features in Playboy and Esquire. In the early '70s, the ultimate set-up was a TD-125 with a Rabco SL-8E linear-tracking arm, often used with a Shure V15 cartridge. Let's just say that over the years since, the TD-125 has held up better than the Rabco.

And then came Linn—eventually. A Scottish company called Ariston produced a belt-drive turntable called the RD11. Design of the RD11 was by Hamish Robertson, along with Jack and Ivor Tiefenbrun (father and son, respectively). The suspended sub-chassis/belt-drive layout was very much in the vein of the TD-150. The RD 11 was built by the Tiefenbruns’ Castle Precision Engineering, which still exists and produces aerospace-grade componentry for military and industrial applications, including the forged aluminum wheels for the Bloodhound land speed record car.

When Robertson left Ariston, Castle set up Linn Products in 1972 as a subsidiary to make turntables. The Linn Sondek—variants of which of course are still made, 47 years later—was essentially the same as the RD11. Ariston produced the RD11s, which featured a main bearing with a captive ball, rather than the single-point bearing at the heart of the RD11—and the Sondek.

Confused? It gets worse. Robertson went on to work with a company called Fergus Fons, which produced a belt-drive turntable called the Fons CQ30. Fergus Fons sued Linn over the design of the single-point main bearing. Even the original distributor of the Sondek, CJ Walker, produced their own turntable for a while.

Long story short: Linn won. All the other brands eventually went away.

Hi-Fi News ad, 1973. Early Sondeks had a rocker switch, grooved base, and prop for the dust-cover. Later--and current---models have a push-switch, plain base, and friction hinges.

Hi-Fi News ad, 1973. Early Sondeks had a rocker switch, grooved base, and prop for the dust-cover. Later--and current---models have a push-switch, plain base, and friction hinges.After that point, belt-drive and direct-drive tables followed a parallel path, until turntables began to vanish from the Earth. Direct-drives have to have very high quality motors in order to last and perform reasonably well. Belt-drives can range from precision instruments like the Linn and beyond, down to bargain basement tables. Most tables from the '80s and '90s which aspired to audiophile cred were belt-drives, like the Harmon Kardon models from the '80s, shown below.

Following the vinyl revival of the last decade, anything goes. There are far too many belt-drive turntables being made today to even attempt a list of them. Look for yourself, and see.

In our next installment, we’ll look at direct drive tables. —and no, they didn’t start with the Technics SP-10. The story is a lot longer and more involved than that.

A Turntable of my Own, Part 4

You are looking at the main aluminum plate that will support the entire table. It is resting on the aluminum plate that was previously bonded to the Minus K platform. In order to prevent this plate from accidentally moving once the entire table is assembled, a 1/8" thick sheet of high durometer rubber was bonded to the Minus K top plate, separating it from the plinth you are now viewing. In order to prevent the plate you are seeing in this picture from moving by an accidental bump, it has been semi-permanently attached to the 1/8” rubber sheet with four 3” diameter circles of two faced tape (one in each of the four corners).

You are looking at the main aluminum plate that will support the entire table. It is resting on the aluminum plate that was previously bonded to the Minus K platform. In order to prevent this plate from accidentally moving once the entire table is assembled, a 1/8" thick sheet of high durometer rubber was bonded to the Minus K top plate, separating it from the plinth you are now viewing. In order to prevent the plate you are seeing in this picture from moving by an accidental bump, it has been semi-permanently attached to the 1/8” rubber sheet with four 3” diameter circles of two faced tape (one in each of the four corners).  We are now ready to begin the final assembly of the turntable. Note two of the four hold down bolts in the corners of the top plate. These bolts are used to firmly attach this plate to the bottom frame supporting the Minus K. This will prevent any accidental movement until the table is fully assembled. At that time, these hold down bolts will be removed, and the table will be free to float. We have placed the 1 ½” thick triangular aluminum support plate on which the main fiberglass plinth is resting. We are now ready to place the 3 drive motor assemblies. Note the brass isolation point and cup, many of which will be used throughout the design of the table.

We are now ready to begin the final assembly of the turntable. Note two of the four hold down bolts in the corners of the top plate. These bolts are used to firmly attach this plate to the bottom frame supporting the Minus K. This will prevent any accidental movement until the table is fully assembled. At that time, these hold down bolts will be removed, and the table will be free to float. We have placed the 1 ½” thick triangular aluminum support plate on which the main fiberglass plinth is resting. We are now ready to place the 3 drive motor assemblies. Note the brass isolation point and cup, many of which will be used throughout the design of the table.

Here we see the anodized VPI chassis blocks being firmly secured to the aluminum sub-plates that were machined, anodized, and filled with the epoxy/lead matrix.

Here we see the anodized VPI chassis blocks being firmly secured to the aluminum sub-plates that were machined, anodized, and filled with the epoxy/lead matrix.  Here we see the table with the platter and one of the three drive motors in place. The parts have all been covered with a removable, protective plastic film. This will prevent any accidental damage to the anodized aluminum parts.

Here we see the table with the platter and one of the three drive motors in place. The parts have all been covered with a removable, protective plastic film. This will prevent any accidental damage to the anodized aluminum parts.  You are looking at the entire table, minus the arms, properly positioned on the Minus K isolator. You will notice the extensive use of the brass points and cups for vibration isolation. Also note the Sutherland Time Line puck placed on the center spindle of the platter. It will be used to set the speed of all three motor drives powering the main platter. It was my original intention to use a Roadrunner tachometer to indicate when the proper speed has been attained but I decided to eliminate it and simply use the Time Line.

You are looking at the entire table, minus the arms, properly positioned on the Minus K isolator. You will notice the extensive use of the brass points and cups for vibration isolation. Also note the Sutherland Time Line puck placed on the center spindle of the platter. It will be used to set the speed of all three motor drives powering the main platter. It was my original intention to use a Roadrunner tachometer to indicate when the proper speed has been attained but I decided to eliminate it and simply use the Time Line.

This picture depicts all three drive motors in place, along with the two Kuzma Air lines and single Kuzma four point tonearm installed.