Over the past year or so I’ve noticed an increasing use of streaming services to supply the music at audio shows and other audiophile events. This article explains why I currently don’t use streaming services and don’t anticipate using them in the future, and instead will likely stay with FM radio. From my perspective, there are a number of significant − indeed, possibly insurmountable − problems with using a subscription-based streaming service to provide your musical sustenance. Individually they are serious, but combined they are fatal.

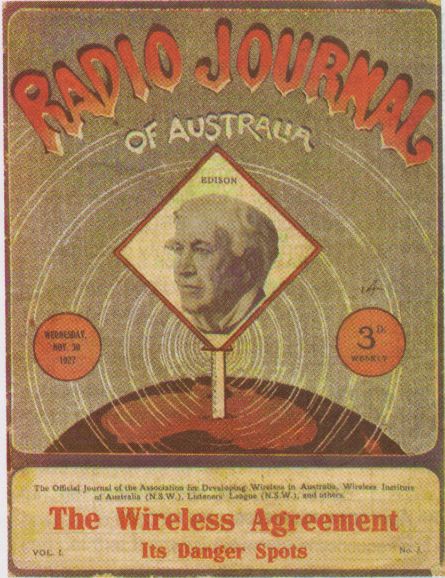

First, the system mirrors the first attempts to introduce a rational scheme for radio (sorry, wireless) broadcasts in Australia in the early 20th century. That scheme failed and I believe today’s streaming systems possess many of the same drawbacks. Some historical background for the non-Australian reader: in May 1923 the Commonwealth government under the new Prime Minister, Stanley Bruce, called a conference to discuss the future of wireless transmission in Australia. It recommended the scheme proposed by AWA (Amalgamated Wireless Australasia, the Australian license-holder for most of the relevant patents of Marconi and Telefunken) in which “sealed sets” would receive broadcasts on a single wavelength (now frequency), under payment by the listener of a licensing fee to the government and a subscription fee to the broadcaster. The annual license fee was 10 shillings for one station, £1 for two or more. Subscription rates varied widely, up to four guineas (£4 and 4 shillings) annually in some cases. That was a lot of money when the average male weekly wage was only £4 or so at that time in Australia. And women got only half that, on average!

Regulations for this “sealed-set” scheme were issued by the Commonwealth in July 1923 and the first broadcast took place in November 1923, by 2SB (later 2BL) in Sydney, using equipment manufactured by AWA. Just under a fortnight later, 2FC commenced broadcasts in Sydney, followed by 3AR in Melbourne and 6WF in Perth the next year. The system was not a success. By the middle of 1924, only 1,206 people across the nation had taken out licenses. The reasons were many. The subscription fees were obviously too high. Listeners wanted to receive more than one station, and many found a way of tinkering with their sets to receive more broadcasts than they were licensed to. Others constructed their own receivers and failed to take out the necessary license − hence the joke at the time of the huge demand among wireless listeners for “star aerials,” ones that come out only at night.

A better system was needed, and a new set of regulations was issued by the Commonwealth in July 1924 that saw the establishment of national A-class licenses, in which advertising was more-or-less prohibited, and lower-power, regional B-class licenses, in which income from advertising and ongoing subsidies from the parent company provided most of their revenue. The A-class stations morphed in the government-owned national broadcaster, the Australian Broadcasting Commission, a few years later, and the B-class stations became today’s commercial stations. This, more or less, is the system under which radio operates nowadays in Australia. It works, and is even better now that FM joined the fray in the mid-1970s along with community-oriented stations (e.g., 3CR, 3PBS etc) a few years later. Both provided program material that substantially expanded upon that offered by the national broadcaster and the commercial stations.

I can’t see too many ways in which today’s subscription-based streaming services differ from the failed “sealed-set” scheme trialed in Australia and around the world in the early 1920s, other than today you choose what you stream and listen to rather than receiving an endless bulletin of wool prices, shipping news, military bands and readings from Dickens, the radio fare most common in the early 1920s regardless of broadcaster.

Second, in all too many cases streaming simply doesn’t work. In September, the Melbourne Audio Club held its monthly meeting with, as is its standard procedure, a manufacturer or distributor invited to display his wares over the evening. The designer/manufacturer of the equipment to be demonstrated struggled for nearly two hours to get the streaming setup to work. The situation was repeated the next month, this time when a club member demonstrated his personal system. His Denon streamer steadfastly refused to say hello to his Yamaha amplifier, despite attempted intervention from various tech-savvy members of the audience. Nope, this level of “success” and “reliability” is not for me.

We've all been there. Courtesy of Pexels.com/Yan Krukau.

We've all been there. Courtesy of Pexels.com/Yan Krukau.

Third, I object to the obligation that a subscription streaming service places on me to repurchase all my music, possibly for the third or fourth time. In many cases I first bought the music as LPs in the 1970s and 1980s. Then I replaced those LPs with versions on CDs in the 1980s and 1990s. Then, for music I really enjoyed, I replaced those early CDs with remastered CDs or even with SACDs in the following decade. And now, if I am to use a streaming service, I’ll have to “buy” it all again? Talk about bleeding the well dry.

This leads to my fourth objection. If I were to go down the track of using a streamer/server, I don’t get to even own the music I’ve just “bought” for the umpteenth time. I merely rent it for a single play. This is pirate capitalism as its most ferocious. Yes, you could burn all your CDs (but not SACDs?) to the inbuilt SSDs that grace some servers but I reckon that, like drinking cheap wine, life is too short to do that sort of thing.

Fifth, using a streaming service means that someone, somewhere, is keeping tabs on what you are listening to. Everything you have ever listened to since joining the service. Everything you ever turned off halfway through. Everything you ever came back to for a repeat listen. Everything that might have a political overtone or provides some sort of social commentary. Listen to Bob Dylan and you are clearly a revolutionary, someone that some group somewhere would like to keep tabs on. Listen to Kylie Minogue or Katy Perry and you can be dismissed as posing no threat to the existing social order at all. God help you if your tastes run to Scandinavian thrash metal, for then you must be a Satanist or some other gross type of deviant.

Ostensibly this tracking of your behavior and listening habits is to allow the provider to tailor music selections to your likes, but I’m not convinced that a more nefarious reason doesn’t lurk just below the surface. Let me introduce the concept of surveillance capitalism. Slowly, surely, inevitably, the provider is building a profile of you. That profile will be sold to a marketing firm − without your permission or awareness, or if the collation and its subsequent sale is declared, it will be in 6-point typeface on page 1,267 of the terms of service. You have no control over this theft of your privacy, other than to refuse to subscribe.

Sixth, let’s address the vexing question of how much the performing musician gets from their music being put on the streaming service. By all accounts it’s trivial, even worse than the pittance most get from the original record company they signed to. Now this is a different sort of capitalism from surveillance capitalism: it is the final, cancer stage of the free market. This is not a metaphor − it’s a diagnosis of the current state of play.

The seventh reason is purely practical. I spend my waking days working on a computer, handling files of obscene complexity. At the end of the day I want to relax without the intrusive and mostly unfriendly technology of devices necessarily controlled by mobile phones or tablets and their various applications. I just want an input selector knob and a rotary, analog volume controller − and a large glass of malt whisky from the island of Isla in western Scotland.

Eighth, and building on my opening concern, is the lurking fear that the whole uber-complex streamer/server edifice will simply give up the ghost and I won’t know how to rectify the problem. This is what happened with the two demonstrations alluded to earlier. Servers require yet another bit of complex instrumentation, yet another thing that has to go through the internet and connect to some bank of servers in some distant, far-off land where electricity is cheap. Yet another unnecessarily complex bit of modern life that will fail. Compare that with receiving a signal on your radio: once you’ve tuned in to the desired station, it works with no further intervention required or constant fear of drop outs.

Finally, and perhaps most critically, my objection is based on the obsolescence inherent in all digital devices such as streaming services. Inevitably, if it’s going to be any good the streamer will be expensive. Anywhere between A$10,000 and A$15,000 has become commonplace. That’s not small change, but it is still no guarantee against rapid obsolescence or failure. An example: a few weeks ago I attended an interview by my friend Peter Xeni (who provides cartoons to Copper) with one of the most highly-regarded repairers of high-end audio equipment in Australia. During our discussions, the repairer made the point that digital technologies have redundancy and obsolescence inborn into them. It is an inherent characteristic and it can’t be escaped. Look at your phone: after two years you don’t (can’t?) get it replaced, even to the point of a simple thing like replacing the battery that now fails to hold its charge. Instead, you throw the phone out in the trash and buy another one, one that is admittedly likely to be (but not necessarily) better and smaller and cheaper.

Ditto with some other items of hi-fi gear (but not FM tuners): CD players of any age or by any manufacturer quickly become well-nigh irreparable, most often because the makers of the drives no longer supply that item, to a lesser extent because the integrated circuits and surface-mount technology in the DACs and amplifiers and sound shapers can’t be obtained anymore. The repair room in which the interview was conducted was littered with CD players that have met their end and awaited an inglorious burial. And they weren’t all cheap-and-cheerful models: I espied more than a few irreparable Accuphases and Mark Levinsons on the to-be-condemned shelf. I myself have an irreparable (but much loved) Cary SACD player sitting in a cupboard at home, the drive having failed.

Compare that situation with valves: the common-as-mud 6SN7, introduced in 1941, is still easily obtainable. Ditto 6922s, EL34s, KT88s etc. etc. Or even compare it with an old-fashioned transistor amplifier; if the components are discrete and not surface mount, there’s a good chance it can be fixed if it plays up. And FM tuners are the most reliable of the lot: there’s simply not much to go wrong in them. Maybe all this is not considered a drawback for most people: audiophiles are often not in the first flush of youth, so who cares if the device won’t last 10 or 15 years. Many consider they will likely be infirm or dead by then.

But it’s not only the hardware that’s of dubious longevity. I wonder how long the current mob of streaming services will last? Will there be a Tidal in 10 years’ time? A Spotify? Those of us with a computer-user background will remember long-vanished word-processing packages. Pity if you have a document in Pfs:Write or PC-Write or Wordstar or Symphony or WordPerfect and want to read it now. Some may think it unreasonable to expect 10 years of service from an (expensive) item of domestic equipment: I don’t. For those with longer memories, who among you remembers the earliest streaming services provided by Rhapsody or Napster? Where are they now? Dead as a parrot. Even MQA, the darling of streamers and downloaders, has lost its luster.

In contrast to buying a subscription streaming service, FM radio provides me with a free way to listen to music I’ve not come across before and has the benefit of the content having been chosen by someone knowledgeable in the field, not by a computer algorithm based on your prior listening habits and an array of dubious assumptions. No one tracking my every listening choice, no one making “suggestions” based on prior listening habits that just reinforce the types of music I’ve already been listening to, with little chance of my being exposed to something truly novel and way out of my musical comfort zone. And the sound quality with FM can be very, very good, especially if you use a tuner with an analog tuning circuit rather than a digital one (e.g., a Magnum Dynalab or many of the high-end Japanese tuners from the late 1970s, the latter now ludicrously cheap on the second-hand market) and a proper, external aerial pointing in the right direction.

FM radio has only one significant disadvantage (assuming you can tune into your station of choice): the inarticulate utterances of so many of presenters who announce the music. Here the curmudgeon in me emerges most fully formed. I often have to “enjoy” my FM radio through gritted teeth when the announcer starts to speak in an inarticulate mixture of phrases and clauses and mismatches between a plural subject and a singular verb and endless dangling participles and, too often, a confusion of mixed metaphors, even on the supposedly erudite national broadcaster. This is the ONLY drawback I find with listening to music via an FM tuner, and it’s clear that only a curmudgeon, a truly grumpy old man, would be annoyed by such trivial matters when the music that emanates from FM radio stations can be so good and so varied and so cheap (i.e., free).

Long live the FM tuner and all those who broadcast to her!

******

Paul Boon is based in Melbourne, Australia. Like many people in their 60s, he came to music and audio equipment in the 1970s while studying at university. In fact, he still uses in his office the first set of components he bought in the late 1970s, a Pioneer integrated amplifier with matching tuner and cassette deck and a Dual turntable with Empire cartridge. All are festooned with silver knobs and buttons and dials and meters, and all have proven astonishingly reliable over those 40+ years. Most gear he bought since those early days he still has and uses in various rooms in his cottage hideaway in the forested hills to the east of Melbourne, almost as a museum of audiophilia. After completing a BSc (Hons) he went on to complete a PhD in the 1980s in marine biogeochemistry and stable-isotope analysis and has worked in those fields ever since, variously as a research scientist, university professor, scientific journal editor, and private consultant. Despite this technical background, he maintains a love of old-fashioned audio equipment, and in particular of tube amplifiers and tuners, not only because of their aesthetics but because their sound is more to his liking. His musical tastes are divergent, but center on early music (e.g. baroque and earlier) and American roots music (like traditional blues and southern soul, tempered with some gospel and western swing).

Header image courtesy of Pexels.com/photo by Pixabay.