Arcade Fire: WE

Jon Batiste: WE ARE

If you asked me up until a few months ago what my favorite band of the 21st century is, I’d say “Arcade Fire.” But after two albums of misdirection and underachieving, Reflektor (2013) and Everything Now (2017), that was in doubt. But I kept the faith, certain that the recently released WE (May 6) would straighten things out. The first single, “The Lightning I-II” was released in March and was very promising, full of apocalyptic visions and self-examination one rarely finds in the Big Rock anthems that Arcade Fire has now mastered:

“I heard the thunder and I thought it was the answer

But I find I got the question wrong

I was trying to run away, but a voice told me to stay

And put the feeling in a song”

But WE relies on Arcade Fire’s well-trod templates rather than feeling. Or it’s too much feeling, and not enough thought. But let’s backtrack.

Win Butler and the Montreal based multi-instrumentalist and singer Régine Chassagne, the daughter of Haitian emigrés, married in 2003. With Win’s brother Will in the band, they became deserved alternative darlings with their earliest albums, Funeral (2004) and Neon Bible (2007). Each touched something special, personal to each listener, yet universal in appeal. In my life, these albums, songs of childhood nostalgia mixed with anxiety, wild abandon, and the subsequent fear, were mesmerizing and evocative. My younger brother David was diagnosed with glioblastoma multiforme, brain cancer, in 2004, and died in 2007: These albums were bookends to that reality. When music does that, it’s miraculous, isn’t it?

(Will Butler left the group after WE was recorded; he’s released some very good solo material during the last seven years for Merge Records, and will have a new album in September.)

Arcade Fire, WE, album cover.

The last excellent Arcade Fire album was The Suburbs, in 2010, which won the Album of the Year GRAMMY in 2011, to the pleasant shock of their fans and the bewilderment of a large segment of the already fragmented mainstream music audience, who wondered: Who is Arcade Fire?

Now, it seems, Arcade Fire are rock stars, perform like rock stars, and Win Butler, all six feet, four Texas-raised inches of him, is a rock star.

But Arcade Fire’s music contains utopian ideals of community, which comes into friction with the idea and purpose of rock stardom. Hence WE. It follows the now familiar Arcade Fire framework of songs named with multiple parts.

One of the problems is this template of multiple sections marked by roman numerals. Song titles in meme structure. How many songs are there on WE? Are there nine, or are there five? They stand distinct on Spotify, for example, but what you have is “Age of Anxiety I” and “Age of Anxiety II (Rabbit Hole)”; a 30 second “Prelude,” then “End of the Empire I-III” and “End of the Empire IV (Sagittarius A*)”; “The Lightning I” and “The Lightning II,” with no parenthetical title/subtitle; and “Unconditional I (Lookout Kid)” and “Unconditional II (Race and Religion)” (featuring Peter Gabriel). The final title song, track 10, stands alone.

The subtitled parts seemed designed for radio programmers and fans to identify: The two singular songs worth noting and appreciating here boil down to “Rabbit Hole” and “Lookout Kid.”

Otherwise, the precious titles effort seems to befuddle rather than illuminate. Too much math for a band that has followed U2 and R.E.M., carrying what’s left of intelligent, ambitious rock bands that started out as “alternative” but entered the rock mainstream. There is too little of that for Arcade Fire to be flailing for its third consecutive album.

The album was produced was Nigel Godrich, known for his work with Radiohead, and Win Butler and Ms. Chassagne. Recording took place in New Orleans, El Paso, Texas, and Mount Desert Island, Maine, but there’s nothing to signify that any local music or culture was absorbed in these expeditions.

Butler has been studying poetry, apparently, with the phrase “Age of Anxiety” summoning T.S. Eliot, and the introduction to Arcade Fire’s video concert, which was supported by Amazon UK and Twitch, features a recitation of Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s beat retort to Eliot in his “I Am Waiting,” which includes the emphatic line, “I am waiting for the Age of Anxiety to drop dead.” It is a centerpiece of Ferlinghetti’s Coney Island of the Mind (1958), which changed the way a new generation of beatniks and hippies and beat-curious identified with poetry. It made American poets part of the resistance to Cold War conformity represented by Little Richard and Gene Vincent, Rebel Without a Cause, and Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

But rock stardom is so hard to navigate these days. So what if “Rabbit Hole” is so catchy: What’s wrong with that? There are almost no guitars audible during the instrumental breaks where the ear craves some electric rock guitar. Instead, it is electric keyboard at the heart of the arrangement, as if the arena in which Arcade Fire wants to compete is dominated by Depeche Mode rather than Springsteen or Radiohead.

The ballads are distillations of early 1970s John Lennon and Neil Young. The Big Rock moments in WE are football chants, singalong moments, shouts designed to sound good. They bring the crowd along in concerts and at festivals, where the real music business is.

Jon Batiste. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/David Becker.

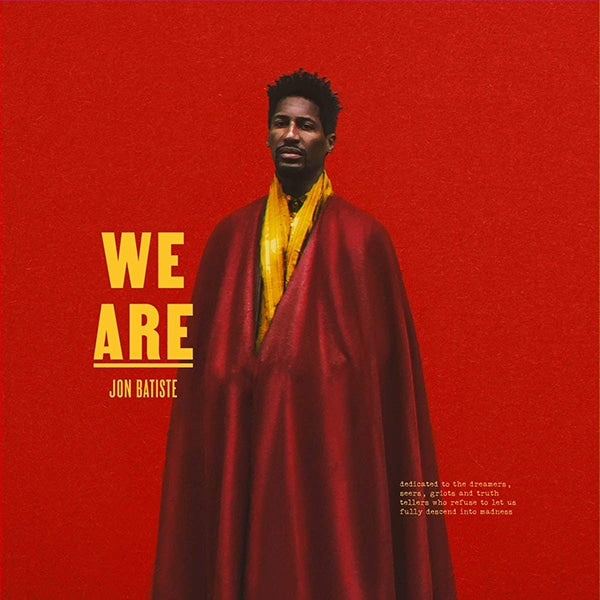

Jon Batiste doesn’t share a lot with Arcade Fire, although there are some odd coincidences: They are both artists whose latest albums contain “WE” all in capital letters; Batiste’s is WE ARE. Batiste is perhaps the most surprising Grammy Album of the Year artist since . . .Arcade Fire.

Until WE ARE won the big prize earlier this year, Batiste was best known as the leader of Stephen Colbert’s late-night band. Grammy awards have always been kind to late-night show bandleaders since Doc Severinsen was nominated for, and once won, a big band category for the recordings made while he was Johnny Carson’s musical friend and foil on The Tonight Show. Times are different now; the people we let into our late-night bedrooms (Kimmel, Colbert) can be a little edgier than Carson, Leno and even Letterman were. Like Letterman’s musical director Paul Shaffer and “The World’s Most Dangerous Band,” Batiste and his confreres are astute and outstanding musicians who can play anything except music that might give you nightmares.

Jon Batiste, WE ARE, album cover.

And so, WE ARE is safe and expertly played. This afternoon I heard Batiste’s breakout song from the album, “Freedom,” playing while I was sitting in the backyard. In the yard, on the radio, it’s very pleasant for a protest song. It’s catchy, but without any bite.

WE ARE is like this all the way through. Every lick is precise down to the bar; Batiste’s mastery at assimilating styles is unquestionable. The music of the Black church (“I Need You”), rap (“Whatchutalkinbout”), dance funk (“Tell the Truth”), jazz, are all seamlessly absorbed. But more is never enough: the title song, with the St. Augustine High School Marching 100, the Gospel Soul Children Choir, and others, is over the top, albeit in a very polite way.

You can listen to this album anytime, anywhere. I expect it will be the playlist of choice at backyard barbecues, family reunions, and friendly gatherings all over the land. As I was listening attentively in my backyard and taking notes, my most music-savvy daughter came over. “It’s perfect background music,” she said. I turned the volume down just a little as we chatted, and chatted, and the music kept on playing, in the background, without ever insisting that we stop talking and turn it up a notch.

Header image: Arcade Fire.