Bruce Springsteen frequently sings about the grit and hardships of growing up in Freehold, NJ. His emotional writing makes it easy to visualize the life experiences he encountered in a small, blue-collar town.

Conversely, my hometown of Roslyn, NY was mostly white-collar and definitely lacking in “grit.” Nonetheless, it didn’t insulate my friends and I from experiencing our fair share of adolescent transgressions, challenges and insecurities. As in many towns, there was plenty of mischief, alcohol and drugs. The hope is that over time, the maturation process to adulthood will tilt the scales between right and wrong. It did for most, but not for all.

Located on the north shore of Long Island, the Old Village of Roslyn has a rich history dating to 1643. George Washington spent five days visiting the area in 1790. In his diary, he noted dining at the home of a gristmill owner named Hendrick Onderdonk, who died in 1809. Well over a century later, an entrepreneur turned the Onderdonk residence into a restaurant, calling it, what else, the George Washington Manor. The centerpiece of old Roslyn village is a beautiful clock tower built in 1895. The village also has a large, tranquil duck pond, a popular gathering place in the 1970s, 1980s and beyond for Frisbee, music and assorted illicit activities.

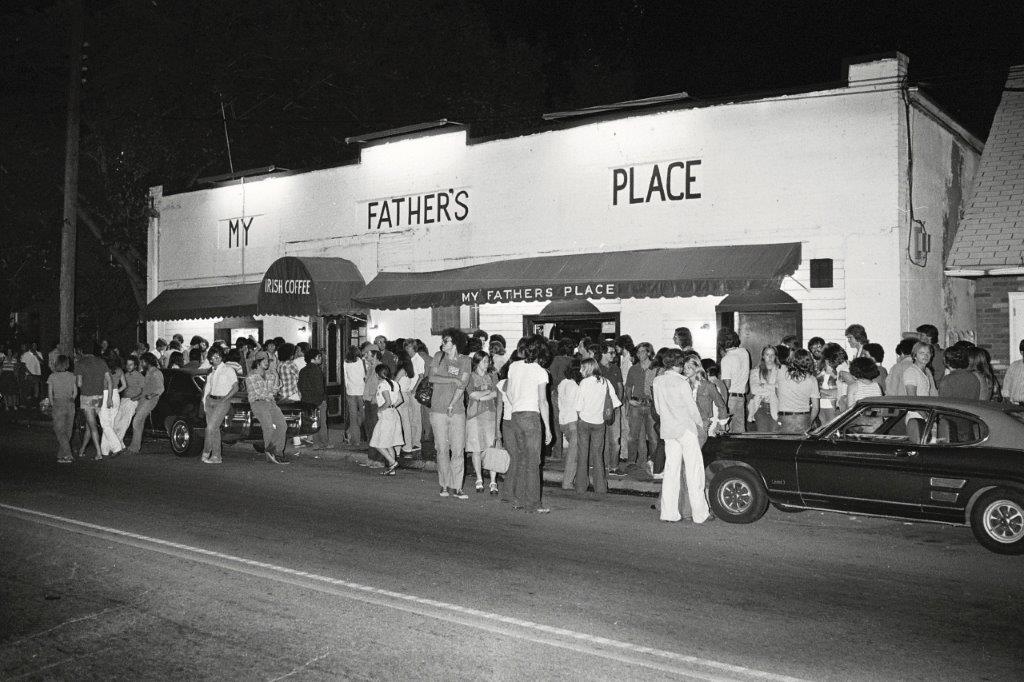

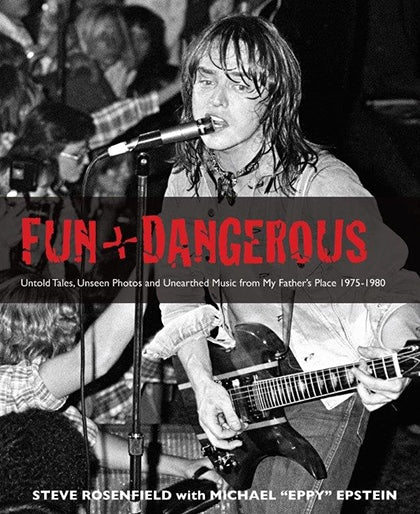

One the very best things about the village during my youth, however, was a small music club located on the east end of town called My Father’s Place (also known as MFP). The club operated from 1971 to 1987 and featured artists from a wide range of genres, including rock, reggae, jazz, soul, country, punk and fusion.

A forward-thinking entrepreneur named Michael “Eppy” Epstein ran My Father’s Place. Eppy was and still is a combination of storyteller, promoter, marketer and, well, a character, and I mean that in a charming and endearing way.

MFP booked both established artists and up and comers, a cast of then-unknowns on the cusp of unimaginable success. Those early performers included Bruce Springsteen, Madonna, Aerosmith, the Police, U2, Billy Joel, Linda Ronstadt, Lou Reed, Stevie Ray Vaughn, Tom Petty, The Runaways, Rush, The Ramones, Blondie, Talking Heads and many more. Artists from the comedy world included Billy Crystal, Eddie Murphy, George Carlin and Andy Kaufman.

Billy Joel. Photo courtesy of Steve Rosenfield.

Billy Joel. Photo courtesy of Steve Rosenfield.That’s right, while in most towns it was a five-minute drive to the nearest 7-Eleven, for Roslyn-ites it was a five minute drive to hear some of the greatest music or comedy ever produced, if you had the foresight (or luck) to catch one of these great “new” artists live.

The club’s bookings were quite diverse. One night you could be entertained by blues great B.B. King, the next night comedian Henny Youngman, and the following night, drummer Buddy Rich. It was a kind of musical circus that only added to the club’s mystique.

Early on Eppy smartly created a partnership with a local and somewhat fledgling radio station, WLIR-FM. It became a symbiotic relationship. Eppy and WLIR first began broadcasting live concerts from a nearby recording studio, before migrating to hosting “Live From My Father’s Place” in 1973. The relationship with the station expanded the club’s reach, appeal and notoriety. Record labels, looking to showcase and develop their stable of young artists, gravitated over time to the integrated club and radio model that Eppy and his partners had created. (Note: In 1982 WLIR re-formatted into a groundbreaking New Wave radio station, the subject of a 2017 documentary New Wave: Dare to be Different.)

A Bruce Springsteen concert was the first live broadcast from My Father’s Place, roughly two years before the Born to Run album made Springsteen a superstar. Legend has it Eppy and “The Boss” smoked a joint backstage before the concert to calm some nerves, mostly Bruce’s. When Springsteen hit the stage, still feeling quite anxious, he looked out at the crowd and said, “Well, here we are, on the radio. Damn, radio’s a nervous business.” Bruce and his E Street brethren then delivered the kind of tight, sweat-dripping set he soon would be famous for.

MFP also presented Billy Joel’s first show after the release of his debut LP Cold Spring Harbor. The club’s Reggae Night shows were pretty special, too. Artists such as Peter Tosh, Toots and The Maytals and Burning Spear performed. The Stones’ Keith Richards and Ronnie Wood would frequent the club’s Reggae Night, dancing it up with other concertgoers and joining the bands onstage.

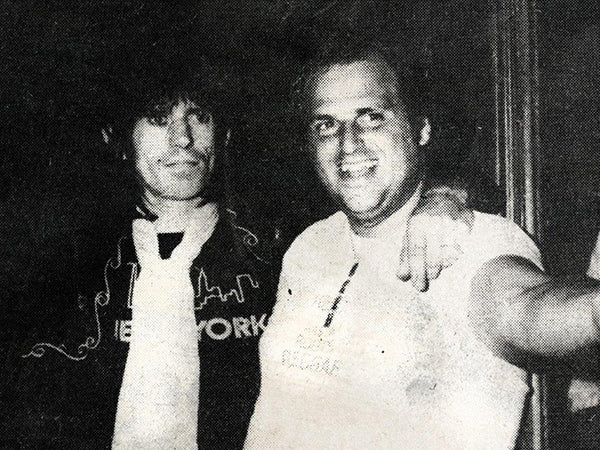

Keith Richards and Eppy Epstein, 1977. Photo courtesy of Steve Rosenfield.

Keith Richards and Eppy Epstein, 1977. Photo courtesy of Steve Rosenfield.

When I asked Eppy if he did all of the club’s bookings from the very beginning, he said, “Yeah, and I didn’t know what the f*ck I was doing. One time I was walking past The Bitter End (a Greenwich Village music club). I see that Carole King is playing there for seven nights, doing two shows a night. So I call up Lou Adler (King’s agent, and a Hollywood music and film legend). I didn’t know Lou, or really even knew who he was (reputation wise), but I knew My Father’s Place was a larger club than The Bitter End. ‘Hi Lou, my name is Eppy, and I have a club on Long Island. I want to make you an offer. I’ll pay Carole King whatever she’s getting for the week (at the Bitter End), and I can do it in one night, two shows.’ Adler laughed hysterically, and then there’s a click. He hung up on me.”

Attending a show at MFP was definitely a no-frills type experience. The venue held 400 patrons seated in long, cafeteria style tables, so the shows had a communal atmosphere, though the patrons were unquestionably there for the music.

The building also had a rich and eclectic history. At one time or another, it was a car dealership, a funeral parlor, a bakery and a bowling alley, which changed its name from Roslyn Bowl to My Father’s Place when the ownership began booking live concerts with a few folk and country artists, a precursor to Eppy and his partners reimagining it as a progressive music club.

As is the case with many businesses, the glory years didn’t come early or easy. MFP’s beginnings were humble and inauspicious. As Eppy shared, the former bowling alley owner, Jay Linehan, was having a difficult time making a successful conversion to a music club. So, Eppy asked him, “What’s your slowest night of the year? If I can fill the place on the worst night of the year, will you give me 49% of the club for $1.00?” Linehan was on board.

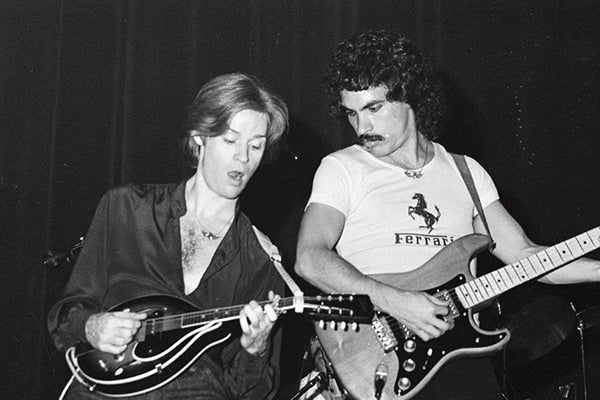

Daryl Hall and John Oates. Photo courtesy of Steve Rosenfield.

Daryl Hall and John Oates. Photo courtesy of Steve Rosenfield.

Eppy then approached his good friend Richie Havens and asked if he would do the gig. This was about two years post-Woodstock. Havens accepted and the first Eppy-led show was on Memorial Day 1971. “Richie wouldn’t take any money,” said Eppy. “Tickets I think were $7 or $8, a lot of money in those days. We ran posters in music stores and clothing shops all over Long Island, and we sold out the show. It was a great night. I then got 49% ownership for $1.00.” This was Eppy’s opening salvo in a long journey of hard work, perseverance and eventual success.

Parking for the club was located under an adjacent viaduct. If you were fortunate enough to avoid the broken glass, the pigeons roosting under the viaduct might leave a parting gift on your windshield. Warts and all, My Father’s Place unquestionably had its unique appeal, as many small clubs often do.

During this period, Roslyn Village was transforming into a “hip” destination, attracting visitors both near and far, while maintaining its historic charm. What lured Eppy to Roslyn to begin with? “I went to a school in Boston. I was studying to be a musician,” he said. “The whole Boston-Cambridge culture scene became my life. We wanted to make Roslyn like Harvard Square, or like parts of Boston that had boutique after boutique. Really cool places to hang out. Roslyn was so different than the other communities on (Long Island’s) North Shore. I thought, this is a cool place to build a little community. There were little antique shops, but nothing to speak of as far as a subculture.”

Other businesses in Roslyn Village (which were there either before or during the time My Father’s Place was active) included a head shop, a record store, a tattoo parlor, a wine and cheese shop, a candle shop, and clothing and shoe stores, in addition to a few bars and restaurants. The town projected a very cool vibe, though in time local politics began to permeate the ether.

As development pressures from the village accelerated, and some small businesses continually flouted local laws – reflecting poorly on the entire counter-culture business community – local bureaucracy contributed to My Father’s Place’s closing in 1987. On the music industry side, disruption was also taking place with record label consolidation, while promo dollars were being diverted to MTV-style videos, not touring.

Though never too far removed from the music scene, some thirty-one years after the original club closed, in 2018 Eppy opened a “new,” smaller My Father’s Place as a supper club in the ballroom of The Roslyn Hotel. The club is a more upscale version of the original, though the music biz these days is a far cry from the heyday of the 1970s and 1980s (COVID-19 notwithstanding).

Reflecting on today’s music industry, Eppy experienced firsthand how well legacy music business models had worked for numerous artists. The old paradigm of A&R vetting, record label signings, radio support, promotion, touring, etc., in his eyes was a proven success, albeit for a limited number of artists. Today’s ease of production and distribution for artists unquestionably “widens the pipe,” but without strong means of discovery, via radio and/or other forms of promotion, for example, he questions how many well-deserving artists will get broadly noticed.

I recently caught up with Eppy for a little Q&A about the origins of My Father’s Place. He also shared an amusing story about first meeting John Belushi. Check it all out below:

Stuart Marvin: Tell me more about the beginnings of the “Live at My Father’s Place” broadcasts.

Eppy Epstein: So we opened the club with Havens in ’71, and then we sat there with a bunch of local folk and country singers. We didn’t have enough of a PA system, so we couldn’t put on any real shows (at MFP). We didn’t have any money at all to build anything, because the money coming in was needed for liquor and beer. I mean, we were so undercapitalized that it was impossible. I’m frustrated. But I had bought some radio ads on WLIR-FM, which just changed format two or three years before. So I asked John Rieger (the station’s co-owner), “what if we get a sponsor and start doing live radio broadcasts?” “How are we gonna do that?” Rieger asks. Well, there’s a recording studio (Ultrasonic Studios) just down the street, 1/10th of a mile away. WLIR’s sales manager, a heavyset guy with a big cigar, then says, “I’ve got a meeting set up next week with Dr. Pepper, some new beverage.” Dr. Pepper then agrees to sponsor us for $500 a week, plus free soda. For $90 a month, we put in a set of (phone) lines to carry a signal from Ultrasonic (where the broadcasts began before moving to the club) to the station. We then connected the line to the board, so we could mix in stereo.

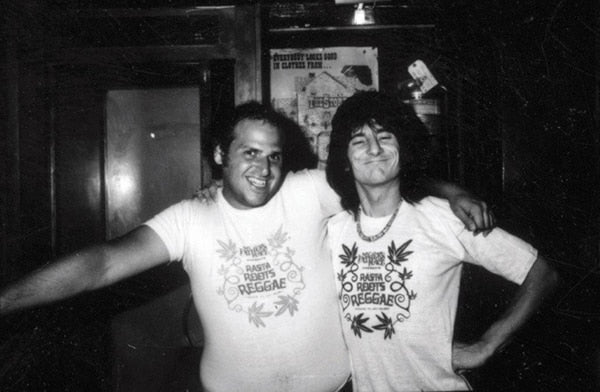

Eppy and Ron Wood. Photo courtesy of Steve Rosenfield.

Eppy and Ron Wood. Photo courtesy of Steve Rosenfield.SM: What about booking talent?

EE: I start calling record companies. I’m already talking to booking agents. I had a club (MFP) and now we had a New York radio station (WLIR), [in] the biggest market in the world, even if it is a Long Island thing. Every record company had a slew of acts, and we had one hour of promo time (on WLIR). It was all about timing. So the acts we broadcast on WLIR were based on whether we got money from the record company, which would pay us $500 for air time, on top of the $500 we got from Dr. Pepper. All of a sudden, local clubs and merchants all wanted to advertise (on WLIR), and we had sponsored concerts (with Dr. Pepper).

SM: Who were the early up and comers who played My Father’s Place who you thought were going to be enormously successful?

EE: Don’t go by me, because I was a musician, I have very left-of-center taste. So, the acts that I thought were gonna come up, didn’t come up, in most cases. So, I’m the wrong guy to ask ‘cause I’m not an A&R guy, and the music I liked was different. I was into hardcore reggae, ska and punk.

Amy Helm and Eppy with picture of Levon Helm. Photo courtesy of Mark Schoen.

Amy Helm and Eppy with picture of Levon Helm. Photo courtesy of Mark Schoen.SM: I know you have tons of great stories, but just share one with me?

The Set Up:

EE: In 1973 or 1974 we do a show (at My Father’s Place) with the touring company of National Lampoon, a magazine that’s part of Harvard University. They played the club on a Saturday night. The trains back to Manhattan stopped at 12 am. They just stopped running. So after the show, there’s a blizzard, it’s snowing pretty hard, and these “kids” are now stranded (on Long Island). So I get in my car and I drive these three kids back to the city (Manhattan). We drive in, but I first take them for a great (early morning) dinner at my favorite restaurant in Chinatown, Wo Hop. It was just a really, really fun night with these three unknown comics.

(End of story, or so I thought.)

The Payoff: (1976):

EE: I had booked the James Cotton Blues Band at MFP. George, the owner of U.S. Blues (a good local bar in Roslyn) calls me up and says, “I hope you’re not gonna be pissed, but I invited Matt ‘Guitar’ Murphy (James Cotton’s legendary blues guitarist) to come over (to U.S. Blues) after your show to teach the guys from Saturday Night Live, the Belushis, the Aykroyds, etc., how to play the blues. Everyone (from SNL) is coming out, and Matt Murphy is gonna teach them the blues.” Matt Murphy is from Chicago, and he’s the real deal.

(Note: Matt “Guitar” Murphy later joined the Blues Brothers Band and had a prominent role in the iconic film, The Blues Brothers (1980).

EE: So I head over to U.S. Blues around 3 am, as they’re just starting out. George brings me over to Belushi and we shake hands. I remember his hands were so clammy. George then says, “Eppy owns that place around the block, My Father’s Place.” Belushi then says, “Oh man, I did your club, and you turned me on to my favorite Chinese restaurant when we moved here from Chicago” (imitating Belushi’s strong Midwestern accent). Somewhat confused, I say, “Mr. Belushi, not only did I never have dinner with you, but you never played my club. I would know if the great John Belushi played MFP.” Belushi then says, “No, no, no, I was in the Lampoon show.”

Then it dawns on me. I realize Belushi was one of the three “kids” I drove into New York City that night, including dinner at Wo Hop. All I had remembered was a girl, a guy, and a fat kid. Funny, nerdy kids. So I start piecing together what he’s telling me and I ask, “who were the other kids in the car with us that night?” Belushi says, “It was me, Radner and Murray” (as in Gilda and Bill). Now I’m totally blown away. I spent an evening (and early next morning) with these three “kids,” who are now world-famous comics. Belushi then excitedly tells me, “during breaks in SNL rehearsals, the entire cast frequently cabs it over to Wo Hop.” They all had become regulars.

Header image of My Father’s Place in 1977 courtesy of Steve Rosenfield.