“The Mindful Melophile” is a new column that will appear in every other issue of Copper. It continues the exploration of best-liked, famous, infamous, and little-known LPs and CDs I started in “My Favorite Things” (Issue 129 and Issue 134). Whenever possible I’ll provide instant listening gratification by including a YouTube link to the music. If you haven’t used YouTube before, a couple of hints: If or when it appears, click on the “no ads” button in the frame so the music won’t be interrupted. And in some instances be sure to stay tuned for additional selections from the album.

Size Counts

Size does count. However it’s not just the size but the way you use it. No, I’m not talking about what you’re probably thinking of…after all, this is a music column. Classical music comes in different “sizes,” from large scale symphonies and choruses to solo pieces that last only a few minutes. Some examples of notable compositions, large and small, are highlighted below.

Striggio: Missa sopra Ecco si beato giorno/Hervé Niquet, cond. (Glossa CD) Early music scholar and harpsichordist Davitt Moroney has referred to Alessandro Striggio’s Missa sopra Ecco si beato giorno as the most extravagant piece of polyphony ever written in the history of Western music. The Mass is the largest and most complex work known to have been composed during the Renaissance and “one of the first great pieces to use architecture and space, with musical phrases physically moving around the ring from choir to choir….There are other large choral works, but Striggio’s Mass is unique with its five eight-part choirs. This is Florentine art at its most spectacular.” [1]

The Mass’ extravagant size played an important role in 16th-century political diplomacy. Size was a powerful attribute for Renaissance rulers. Princes, emperors, and popes became patrons of enormous civic art works and architectural structures to demonstrate their strength and show they could outdo the great works of the ancient Romans and Greeks. Striggio, a musician who worked for Cosimio de Medici’s Florentine court, was commissioned by the ruler to compose “gigantic music” that would help him earn the title of king. The Mass was written with 40 different parts (expanded to 60 in the Agnus Dei) because there were only a few courts in Europe capable of performing a work that large. The message to other leaders was that the Medici family could promote culture on the same grand scale as the most powerful rulers in Europe, therefore Cosimio should be a king, too.

Cosimio sent the Mass to the Holy Roman Emperor as a present and to compliment him for being one of the few rulers who had enough resources to perform it. Although the Mass was a success, the Emperor didn’t want to grant Cosimio the title of King of Tuscany and named him Grand Duke instead. After performances in several cities the Mass was lost for 400 years until 2005 when Moroney located a complete set of part books in Paris. The composition subsequently received its first modern performance at the BBC Proms classical music festival in 2007.

Ives: Symphony No. 4/Leopold Stokowski, cond. (Columbia LP) Ives’ Fourth Symphony, with a greatly expanded orchestra as well as a chorus, is not only “big” in a literal sense but extraordinarily complex, usually requiring three conductors to hold things together. When it was written in 1916 sections of it were unlike anything else being composed at the time: a combination of Protestant hymns and overlapping bands (each band playing its own parade music) plus a crazy quilt of American parlor songs, marching tunes, ragtime melodies, and patriotic songs.

The symphony’s first performance occurred 50 years later in 1965 at Carnegie Hall and the Columbia LP referred to above was recorded using the same artists who performed at the premiere. Reviewer Harold C. Schonberg wrote in The New York Times, “…it throws up spiky walls of sound and then sings the simplest of songs. It has wild polyrhythms, clumps of tonalities that clash like army against army, Whitmanesque yawps and – suddenly – the quiet of a New England church…the work is a masterpiece.”

Ives used a variety of innovative devices long before they appeared in the works of Schoenberg, Stravinsky, and other major 20th-century composers. His avant-garde compositions also influenced composers like Henry Brant, who incorporated space as an essential part of his music. In Brant’s own words: “Ives’s simultaneous presentation of wide spatial separation of performing forces, unrelated harmonic materials, colliding and violently contrasted melodic formations and rhythmic combinations of unpredictable irregularity have been points of departure for everything I’ve done since 1950. Few composers care how the instruments are placed in the hall – it’s a matter of conventional routine. For me, it is an expressive requirement.” [2]

To better understand the symphony, watch conductor Leonard Slatkin’s introduction, then move on to the historic televised performance with Stokowski leading the orchestra.

Slatkin:

Stokowski:

Mahler: Symphony No. 8 – Symphony of a Thousand/George Solti, cond. (Decca LP or CD) According to the original program prepared for the symphony’s premiere in 1910, the work required 858 singers and 171 instrumentalists – a true symphony of a thousand, although Mahler didn’t refer to it that way himself (the title was added for promotional purposes).

My favorite recording is the one conducted by Georg Solti with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1971. It doesn’t have the natural perspective of more recent recordings and the organ part is dubbed, but it’s a dramatic reading in full-bodied sound. This rarely-performed piece (due to costs) is sublime: it holds my attention for the entire length of over an hour and leaves me richer for the experience.

The CD review in Gramophone magazine parallels exactly how I feel about Solti: The recording “conveys a feeling of a great occasion…[it] takes off and soars from the very start, so the impact of the great opening on ‘Veni, creator spiritus‘ tingles here with electricity…At times the sheer physical impact makes one gasp for breath, and I found myself at the thunderous end of the first movement shouting out in joyous sympathy, so overwhelming is the build-up of tension.”

As much as I like the Decca recording, start with the Bernstein example listed below. It’s a terrific video of his 1975 performance with the Vienna Philharmonic and helps listeners better understand the music by cutting back and forth among the choral singers, soloists, and instrumentalists. The Solti video only has a few images to look at but does display a translation of the text. Check it out at another time: This is exhilarating music and time well spent listening.

Solti:

Bernstein:

Satie: Avant-dernières pensées/Alexandre Tharaud, piano (Harmonia Mundi CD)

Musical miniatures are short pieces that usually have their own forms instead of the prescribed ones found in large creations for opera stages and concert halls. Pieces are often strung together as suites and have their origins in piano music performed at 19th century salons.

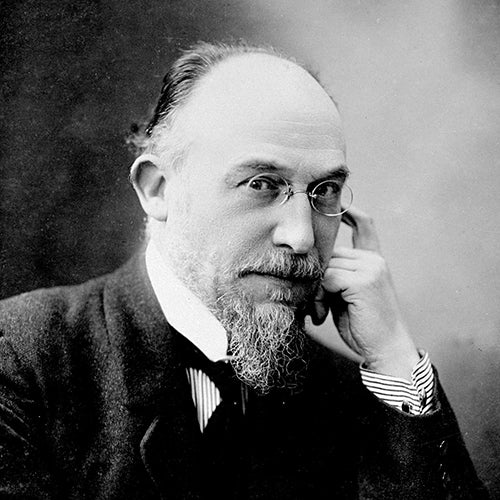

There’s a good chance you’ve heard Erik Satie miniatures in movies (e.g., My Dinner with Andre), on various TV programs, and almost always on recordings that feature music for relaxation. His most famous piece is the languid “Gymnopédie No.3” from a set of three piano pieces composed in 1888. Tharaud gets it just right: not too slow, not too fast, without trying to make it dramatic or more interesting by breaking the flow with heavy accents. After all, the eccentric Satie referred to many of his compositions as “Furniture Music” intended to be ignored like background wallpaper.

One of the most intriguing parts of this album is Sept pièces pour piano – seven dances from the theatrical work Medusa’s Trap. At its private premiere in 1914 Satie placed sheets of paper between the strings of the piano, resulting in a “straw-like” sonority that reflected the only dancer in the work: a mechanical monkey stuffed with straw that moved about while the other characters dozed or left the stage. Satie, along with Ives, anticipated the work of later composers including experimenter John Cage. Cage was famous for inventing the prepared piano in 1939 but Satie foreshadowed Cage’s creation by over two decades. Satie also influenced minimalists Philip Glass and Steve Reich as well movements like Dadaism and the Theater of the Absurd.

Tharaud: Track 3 (“Gymnopédie No.3” at 4’50”) and track 12 (“Sept Pièces pour Piano” at 28’00”):

Various: Themes from Horror Movies (Coral LP) Music to accompany an enormous spider going after its dinner or a gargantuan house cat chasing its prey? Music to relax by in a chair built for a giant? No, it isn’t the score from the movie Attack of the 50 Foot Woman or The Amazing Colossal Man. It’s the unusual theme music by Irving Gertz from the 1957 film The Incredible Shrinking Man – unusual because a theme with jazz elements led by the likes of band leader Ray Anthony (on this LP performed by Dick Jacobs and His Orchestra) is rarely, if ever, found in sci-fi/horror films of that period.

While standing on his boat, Scott Carey (about to become the shrinking man) passes through a mysterious cloud that appears on the water. Back at home he soon finds himself getting smaller and smaller…so small he has to avoid being mauled by his house cat and eaten by a spider. As Boris Karloff says on the LP before the music starts: “He was saying goodbye. He got smaller…tinier….” At the end of the film we leave the (still) shrinking man, no taller than a blade of grass, thinking about how much smaller he can get and how he will matter in the universe. What will he find? What will he become? Scott reaches the conclusion: “To God, there is no zero. I still exist.”

A jazz-influenced theme, famous big band leader, Theremin (an early electronic instrument used primarily in sci-fi/suspense films and to play the theme on TV’s original Star Trek), a strangely moving and spiritual story, menacing introduction by horror film star Boris Karloff, and a monster spider…what more could you ask for from a miniature piece of music just over three minutes long?

Themes from Horror Movies (1959): The version on the album referred to above can be found here:

Classic 50’s Original Science Fiction Film Scores (2011): Another interpretation, more relaxed and very enjoyable but minus the Theremin and Karloff’s introduction can be found at this link:

[1] UC Berkeley News, November 2007 and personal interview

[2] Henry Brant, May 2006 (quoted on his website)

Header image of Erik Satie courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Sonia y natalia.