It appears my earlier essay on declining hearing (in Issue 160) touched something of a nerve, so to speak. I appreciate the many thoughtful comments it prompted. Perhaps I should not have been surprised that they focused primarily on the question of hearing and using hearing aids, and not so much on how our changing hearing intersects with those recording and playback qualities, whatever they are, that result in a realistic representation of actual musicians playing in a space.

While I respect the expertise of the industry insiders whose work appears in Copper, I suspect many of those reading are, like me, laypeople who may be uncomfortable speculating about things that are outside our respective wheelhouses. And in this case, those things may be unknowable anyway – as I’ve mentioned before, if the secrets of great sound were known to one and all, every recording would be wonderful, and we know that’s simply not the case (though I do believe that, pop music’s compression and loudness wars aside, there are more good recordings issued now than at any other time in the industry’s history). Or it could simply be that hearing loss is intensely personal and potentially frightening, especially to those who take great pleasure in music and sound, and that fact elicited the need for people to share their own experiences. Community is comfort at times, or in this case at least solace.

But before I leave the question of perceived recording quality completely, I want to touch on something that editor Frank Doris wrote in his earlier Copper article on hearing loss. His comment, shown below, speaks to one particular aspect of the ability to discern quality in hi-fi, even with declining hearing:

“We’re constantly comparing the sound of our systems with the sound of reality as we perceive it. We know what our systems should sound like, whether hearing-impaired or not, and configure them accordingly.”

What most of us search for in the reproduction of music in our homes is a reasonable simulation of the real thing. That goal is constant – it doesn’t change with age. Our hearing performance does, but many of us are finding that, as generally regrettable as diminished hearing is, it doesn’t matter as much as we’d expected when it comes to what we value in our sound systems. I believe the reason is that our yardstick for subjective measurement of the system’s performance has changed as well. What I think Frank was saying (and he may correct me if I’ve misconstrued his intent) is that our perception of the aural world around us is the only auditory standard we have at any given time. [No contradiction, Craig; you’re right – Ed.] When our ability to hear diminishes, then our perception of the real world, the standard to which we hold our systems’ performance, diminishes too, as unappealing as that might sound.

The fact is, it’s physically impossible for an old person to utilize a young person’s perception of reality as a standard against which the old person measures the perception of his or her sound system. All we know is what we ourselves perceive. At any age, the goal is for the system to conform to our contemporary standard of reality. The fact that many of us believe our systems sound just as good or better now than when we were younger appears to confirm this, and it speaks, at least partially, to my earlier premise that extended high-frequency response is not the primary auditory cue that results in perceived realism. The flip side of that coin is that our diminished hearing may also be masking certain undesirable performance characteristics that had been detracting from realistic sound. But that’s a rabbit hole I don’t care to go down.

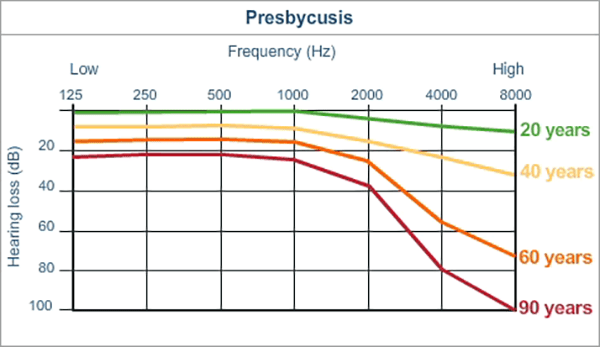

Graph showing presbycusis, or the normal aging of the ear, according to age. From the cochlea.eu website.

So where am I now in my own journey? At my last writing, I was waiting on delivery of a pair of hearing aids. I won’t mention the manufacturer or source, other than to say I did not consult a certified audiologist, but neither did I go the full-bargain route of ordering on my own from the new proliferation of internet-marketed devices. I don’t mean to disparage either approach – I simply decided that my degree of hearing loss didn’t warrant the former, and I distrusted my ability to guide myself through this maze, without any help, of the latter.

I’ve now had my devices for a little over two months. They’re of the “open fit” variety, where there is no full occlusion of the ear canal. I use them every day, and they’ve helped in most day-to-day situations, though because we’re not entirely post-pandemic, two of the circumstances for which I got them – hearing my dining companions in a noisy restaurant, and understanding speech clearly in large public meetings – haven’t presented themselves yet for evaluation. But my return privileges last another four months, so I’m sure there’ll be time before that deadline to try their performance in those environments and judge them accordingly.

Day-to-day, I think I’ve come to terms with the aids, and I can appreciate what they can do, and what they can’t. It took some time to adjust to them initially. It was very easy at first to be distracted by the new hypersensitivity to sounds I’d become accustomed to not hearing, like rustling of nearby papers, or the sound of walking through our home (pops and creaks in flooring, shuffling of footwear on carpets and rugs). Besides training of the brain, that adjustment has been helped along by the provider supplying a remote-control software program through which the devices gradually ramped up to my prescription level, tuned ultimately to offset my measured losses. That process took about three or four weeks to complete.

The biggest problem I perceive with them is an unnatural sound quality in high frequencies that is akin to a slight buzzing, like there’s a loose screw vibrating in the rim of a speaker basket. Being a sometime guitarist, it occurred to me one day that it’s very much like the dreaded B string fret buzz, but applied to all high-frequency sounds. I’ve confirmed with three other users of this device that they hear the same thing, so I think I can effectively rule out a faulty sample. And my brain has already tuned this sound out on most human speech, but on certain musical instruments, like piano, it can be quite distracting, sometimes making notes seem unnaturally bright, other times making it sound almost like the instrument is unstable or wavering, like it’s under moving water. Its severity, and in fact its very presence, can change from moment to moment, which almost makes me wonder if there’s some bit of phase-shifting taking place.

I know from several of the comments left in response to my original essay that there are some manufacturers who may be more capable of producing devices better suited to music listening, or audiologists who are good at fine tuning devices to eliminate or reduce this or other effects for those who must use their ears critically all the time. I chose not to go that route for now, since, as I’ve mentioned before, I have no problem extracting maximum enjoyment from my sound system without hearing aids – I simply take them out when I listen to music. If it gets to the point at which listening without them ceases being enjoyable, and I find the need for hearing assistance under all circumstances, I may reconsider.

The highly-rated Lively 2 Pro headphones with control app. From the Lively website.

And that may happen in time. I’ve had a brief glimpse into that possible future, and it was frightening. One day, several years ago, I woke up to a general “stuffiness” in the right side of my head (though not “stuffy” in the sense of any kind of breathing congestion). I didn’t think much of it until I realized while listening to the radio on my morning commute that my right ear was hearing at much lower amplitude than the left, and the lower frequencies of the right ear were especially diminished and badly distorted. Sounds in general, especially loud ones, were extremely annoying, like trying to understand speech in a reverberant space while blocking one ear (a pastime of bored students everywhere). By the time I could get to see my doctor, it had cleared up on its own, and he couldn’t find the evidence of anything amiss. Well, that’s happened again, several times, just during the past few weeks. Each time it’s “fixed” itself within a day or two. Just by chance, it happened last month while I was seeing the doctor for other reasons. After a lot of peering, poking and prodding, he told me it was due to a small bit of fluid buildup behind my eardrum that was not being drained properly by my Eustachian tube. He said that a decongestant might help, but said it was also just as likely not to. And so, the condition remains, for now a thankfully sometime annoyance. When it flares up, I simply don’t listen to music. But if it ever becomes a chronic condition, or heaven forbid, a permanent one, I may need to seek a more robust hearing intervention, whatever that might be.

In the meantime, I’m trying to protect the hearing I have, and I remain grateful for every minute of “normalcy” it still provides.

Header image: school health services hearing test, 1946. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Queensland State Archives.