AES Europe Spring 2022 was held at The Hague in The Netherlands from May 16 – 19, 2022. The overall high standard that the Audio Engineering Society has maintained in their trade show events has been impressive, and this latest event was no exception. The range of online panel discussion topics and educational exhibits alone provided a wealth of insights to professional audio engineers and audiophiles alike

The on-demand streaming of events, developed as a result of the pandemic, has become an essential tool for many, with the added advantage of enabling participants to monitor numerous events that may have overlapped or been held simultaneously in real time. AES is to be commended on its emphasis in ensuring the availability of these resources. As a result, I am selecting a cross-section of different events to cover that I believe will be of particular interest to Copper readers.

Why Does Anyone Still Invest in Analog Equipment?

Swiss audio engineer Daniel Dettwiler has developed a formidable reputation, specializing in recording and mixing film scores and acoustic jazz with world-class orchestras and ensembles. No less a luminary than the late Al Schmitt sang praises for Dettwiler’s work.

One of the first events was his presentation: Why Does Anyone Still Invest in Analog Equipment?

Hosted by MC and composer Oisin Lunny (who was the MC for practically all livestream and in-demand content for AES Europe Spring 2022), Dettwiler weighed in on a topic that has divided camps in both the audiophile as well as audio engineering/production arenas: the preferences and criticisms in the digital vs. analog equipment debate.

Dettwiler recalled that when he first began his career around 1990, he was already sold on Pro Tools (the industry-standard computer audio production software) and digital technology, and admits to being resentful at the time about having to train on a huge analog console, wind tape on Studer machines, and move heavy studio gear, whose sounds could be replicated with plug-in software. He also candidly admitted that back in those days, he could not hear a difference between digital and analog recordings. However, Dettwiler conceded that his early teachers had a bias in favor of computers and digital recording, which colored his initial impressions and his dismissal of the sonic differences between digital to analog and analog to digital converters, among other gear.

Daniel Dettwiler. Courtesy of AES.

Dettwiler’s first intensive A/B comparison experience between analog and digital was the result of a challenge from a friend who only mixed on analog (using a Solid State Logic console) and claimed audio superiority over anything Dettwiler could mix in his Pro Tools-equipped home studio.

Over the next 20 years, Dettwiler found himself continually stumped by certain EQ challenges and mixing obstacles that could not be resolved through software and give him the sounds he heard in his head. As a result, he started investing in analog outboard gear to provide certain audio intangibles, such as warmth, smoother boosts, and other qualities unobtainable digitally.

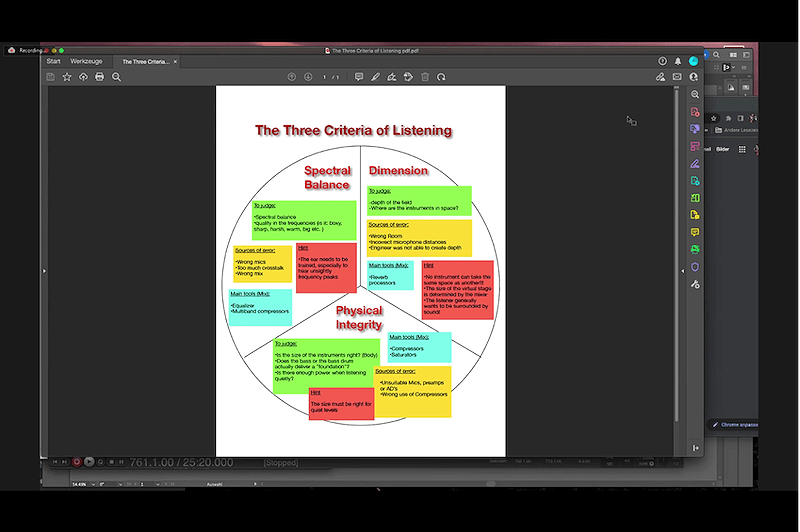

Starting from the recording process onward, Dettwiler referred to his “Three Criteria of Listening” principles and the notion of “physical integrity” of instruments being captured. He noted that he wants an instrument, like a tenor sax, to sound as close as possible to the real thing at a very low listening level so that it will retain its sonic qualities when raised in volume in a mix with other instruments.

In comparing digital and analog formats for mixing, Dettwiler pointed out that digital has a huge dynamic range with a sound that doesn’t alter if mixed “hot” or not, while analog has a noticeable noise floor, a narrower dynamic clean range up to unity gain, and then some minor harmonic distortion and saturation with a perceptible “glue” that holds a mix together up to +10 dB, with a “punchier” sound and added harmonic distortion up to +25 dB, at which point heavy distortion can ruin a mix if it passes the +25 dB level.

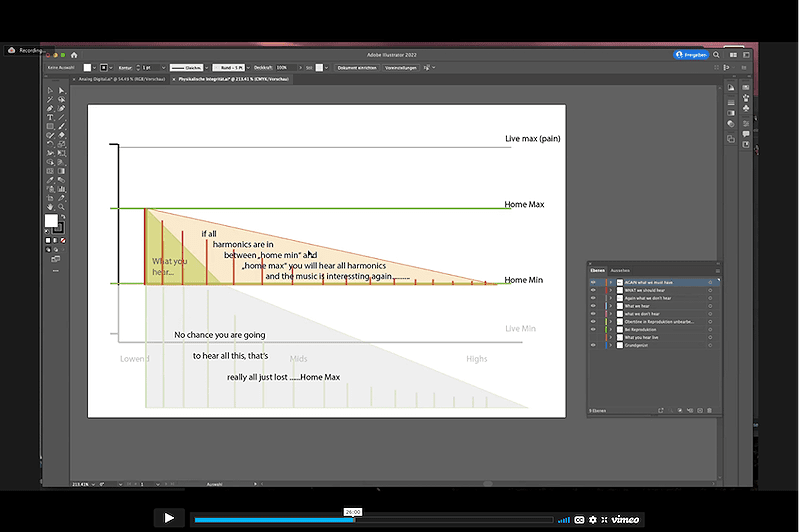

Dettwiler stressed the importance of dynamic range and high “physical integrity” in his recordings because, in his opinion, the final commercial product that goes out to audiophiles and music lovers alike should contain as much of the harmonic content as possible from his original mix.

Daniel Dettwiler’s “Three Criteria of Listening.” Courtesy of AES.

While some audiophiles will often own equipment that has specifications designed to reproduce a good portion, if not the entirety of harmonic content from his mixes, he acknowledged that a sizable proportion of that harmonic content might never be heard by the majority of listeners on their home hi-fi systems (see chart).

Therefore, when heard on an average home audio system, the narrower dynamic range of analog equipment can actually help to “restore” the harmonic content that would ordinarily be “lost” from a digital format that ironically would be closer to sonic reality!

Although all of the mixing and A/B sound comparisons of tracks, guitars and drums that Dettwiler demonstrated were from digital stems and multi-track files, he explained how the use of analog equipment, such as the Pulsar 1178 compressor, can be used to restore the harmonic content of an instrument that loses those aspects at lower volume levels.

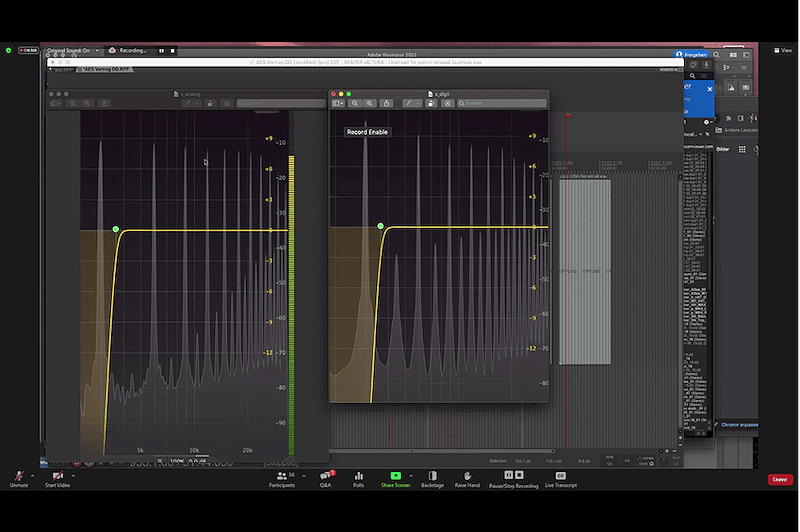

Interestingly, Dettwiler’s analyses have led him to conclude that there is an underlying degree of analog-friendly harmonic distortion that we gravitate towards as a sound that is pleasing to the ear, and which is extremely difficult to recreate with plugins in the digital realm. The problem is that trying to reproduce this aural effect digitally often results in aliasing, which can ruin a mix and has a noticeably “artificial” sonic quality.

Daniel Dettwiler’s harmonic content chart. Courtesy of AES.

Dettwiler showed charts that displayed the harmonic distortion generated through analog gear at 3 kHz and 6kHz (on the left of the chart below). The right chart displays the attempts to reproduce the harmonic distortion using digital plug-ins, and shows an unacceptable level of added aliasing and latency.

Dettwiler was quick to emphasize that unlike many of his peers who started on analog and then were won over to digital, he was basically a hardcore digital fan who was seduced by the sound options offered by the analog realm. He sees both technologies as equal but different and will take whichever one best delivers the sound he envisions while mixing, a job that draws more from emotion than from analysis – at least for him.

Analog harmonic distortion (L) vs. digital harmonic distortion (R). Courtesy of AES.

The Potentials and Limitations of Audio Wearables

Audio wearables are a new frontier in portable high-fidelity sound. They’ve gone beyond in-ear and over-ear headphones to include products like sunglasses with built-in audio, clip-on and neckband Bluetooth speakers, and even a vest that delivers 360-degree audio! The Potentials and Limitations of Audio Wearables featured a panel of accredited people from a wide range of fields to discuss the topic.

Moderator Thomas Gmeiner started off the presentation by describing his work with established audio companies like Sennheiser, as well as with fashion companies seeking to incorporate microphones and speaker systems into clothing. He also noted the challenges in overcoming extraneous noises that such a design task imposed, from wind and exterior noise to the sound of the clothing fabric itself – all of which can impede the sound quality of the desired microphone or speaker system.

Thomas Gmeiner, wearable audio presentation, courtesy of AES.

He also mentioned potential applications in other professions where portable, yet clear sound for communication is an important component of the job, such as heavy construction, aviation, and audio for sporting events.

Aili Niimura, a spatial audio designer for Microsoft Mixed Reality, discussed developments in virtual reality (VR) sound and in creating holistic sonic environments.

Pauli Minaar of IDUN Audio summarized the large growth in wearable audio, which he attributes primarily to edge computing and how significant increases in processing power and memory have made the use of multiple sensors and connection to 5G, Wi-Fi, ultra-wideband (UWB) and LE Audio (the next, upcoming generation of Bluetooth audio) a reality. He also noted that a trend towards people not using smartphones as conspicuously in public, in favor of using more discreet devices like earbuds and smart watches. This has also increased interest in wearable audio, which is also tied into the increased consumer consumption of podcasts, music, audiobooks, and audio-based media.

One of his areas of research is in the use of dynamic spatial audio processes for sound picked up by wearable sensors, in order to transmit localization of sounds for the listener in an enhanced fashion.

Aili Niimura. Courtesy of AES.

Amy LaMeyer represented the venture capitalist perspective on wearable audio. Her WXR Fund specializes in early-stage financing of VR, AR and AI companies who have female executive management.

Matt Neutra, who worked with Amy and Aili to design an AR product, mentioned that the obsession with technology results in frequently overlooking the human brain and the psychological aspects and impressions that are derived from the technology, and which are, ironically, the impetus for developing the technology. He is especially fascinated as to how spatial audio can be rendered through hardware, to now exceed the capabilities of human hearing.

The last guest was Jan Abildgaard Pedersen. A former executive consultant to Bang & Olufsen, Dion Audio and Amazon, he commented about the physical limitations of wearable audio, such as the tiny size of the microphones, the limitations of near-field audio, limited power (battery) capability, and limited audio bandwidth. However, he does see wearables as an excellent innovation platform for combining audio and sensors with other technologies and applications.

Neutra commented that wearables can subdivide their sensor functions to augment Bluetooth capability, separating low-, mid- and high-frequencies and routing the audio to different speakers or performing processing for headphones to create artificial spatial location. He noted that making the user experience the most important aspect was the best impetus for faster development towards commercially-viable products.

Amy LaMeyer. Courtesy of AES.

Gmeiner noted that the increased use of wearables featuring concealed microphones and cameras could create new issues regarding privacy and unauthorized recording, topics that the product developers have frequently overlooked.

Matthew Neutra. Courtesy of AES.

Minaar cited that one of the goals of wearable audio designers is to migrate the focus from the smartphone being the hub device around which other devices are viewed as peripheral, to the wearable being the new hub, in which a smartphone is but one of several interactive devices.

LaMeyer stressed the importance of comfort and ergonomics, especially with wearables meant to be worn for extended periods of time. Her past experience made her aware that VR headsets that were too complex to use and uncomfortable to wear had created obstacles towards commercial acceptance.

The panel, overall, was in accord with the future prospects for wearable multimedia platforms and specifically, wearable audio.

Audio Archiving and Restoration: A Special Focus on Collections Recorded on Analogue Discs

A topic near and dear to the hearts of all music-loving Copper readers is audio archiving and restoration – especially for recordings that would otherwise be lost to antiquity. Audio Archiving and Restoration: A Special Focus on Collections Recorded on Analogue Discs featured a panel discussion including:

Nadja Wallaszkovits – Vienna Phonogrammarchiv audio engineer and Professor for Conservation of New Media, University of Stuttgart

Ilse Assmann – sound and A/V conservation consultant, University of Johannesburg

Jessica Thompson – GRAMMY-nominated mastering and restoration engineer

Brad McCoy – senior studio engineer, Library of Congress

Rob Allingham – South African music archivist and film sound engineer

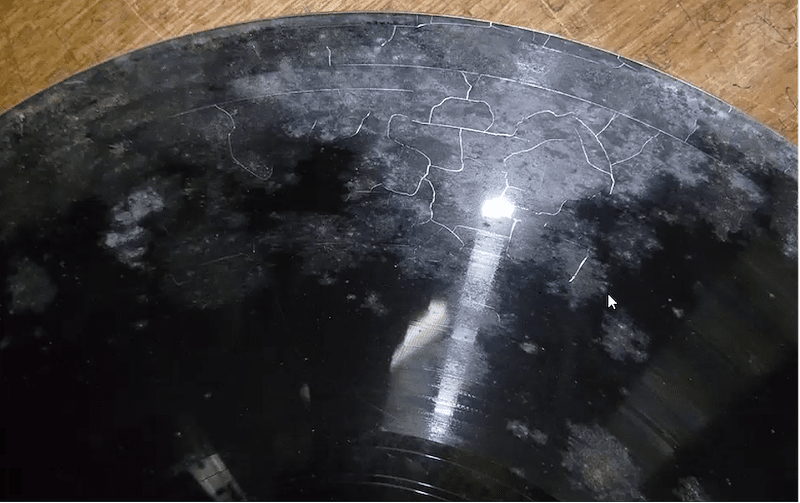

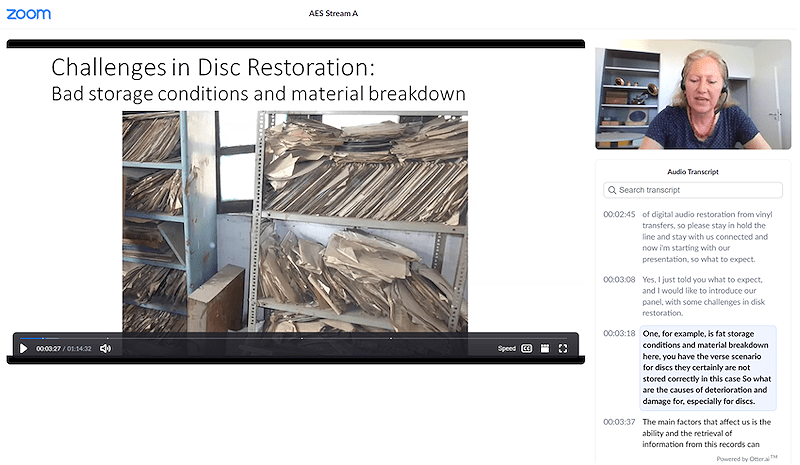

Wallaszkovits began the presentation with a checklist of specific challenges faced by preservationists and archivists, such as poor storage conditions that accelerate deterioration of discs or tapes. This manifests in a number of ways:

- Warping and breakage

- Dust and dirt contamination

- High humidity and temperature, which can lead to acetate brittleness, mold, and other problems

- Poor handling, leading to scratches and surface damage

As an example, she cited an old shellac recording that was warped like a potato chip. The restoration specialists were able to apply extreme cold refrigeration and center pressure from a CD (they used an actual CD as a flattening device) in order to sufficiently flatten the disc and get an acceptable transfer for archiving.

Another key area of restoration and recovery in archiving is in the replay system: variables between turntable speeds, types of styli, equalization options, and other parameters intended to maximize sound replay and minimize extraneous noise can yield a wide range of results.

Wallaszkovits cited the use of the AES playback-standard curve established in 1950 (i.e., a 400 Hz bass turnover and 2.5 kHz treble transition frequency) and how it differed from the commonly-used RIAA playback curve established for vinyl records in 1953.

Examples of bad disc storage conditions. Courtesy of AES.

Ilse Assmann and Rob Allingham discussed their work in the restoration and preservation of old South African 78 rpm recordings. Allingham recounted the early history of recording in South Africa and Cape Town in particular, from the very first spoken word records by the London-based Gramophone Company in 1906 and going into the Depression era, where pioneer Eric Gallo created the indigenous South African music recording industry with his first records, after years of importing American records for the South African market.

While World War II halted the bulk of activity in South Africa, Gallo convinced his good friend, Sir Edward “Ted” Lewis of Decca Records in the UK, to declare in a 1960 speech that South Africans were the largest record consumers in the world on a per capita basis.

The South African recording industry had exploded after the War, and scores of private companies, each with as many as a dozen or so separate labels, emerged to cater to the widely diverse South African market, which was audience-subdivided by different tribes, languages, and demographics.

Some of the countless South African record labels from the 1950s and 1960s. Courtesy of AES.

Allingham noted that the relative insularity of South Africa resulted in the 78 rpm format still being used as late as 1968. As a result, a significant portion of South African masters have been lost to history, since those records were made from direct lacquer masters that eventually wore out or broke, rather than from tape. He has thus become especially precise in his restoration work when it comes to stylus choice, since the range of lacquer master quality was so wide, and optimum transfer of sound information can only be derived from choosing the best stylus to match the groove curve depths of each particular disc, combined with the right EQ to maximize fidelity.

Allingham summed up the task as one so monumental that to fully accomplish it might take a cultural initiative on the part of the government or by institution-level funding by private collectors who view the project as a historic and cultural imperative.

Audio engineering preservation specialist Brad McCoy’s presentation detailed the work he does at the US Library of Congress. The massive Culpepper, VA repository holds:

- More than 1 million moving image collection materials, including movies, TV, commercial ads, educational, and industrial content

- More than 3.6 million audio collection commercial recordings, radio broadcasts, and historic recordings

- More than 2.2. Million supporting documents in the form of photos, screenplays, press kits and manuscripts.

The collection grows at the rate of approximately 150,000 new items per year.

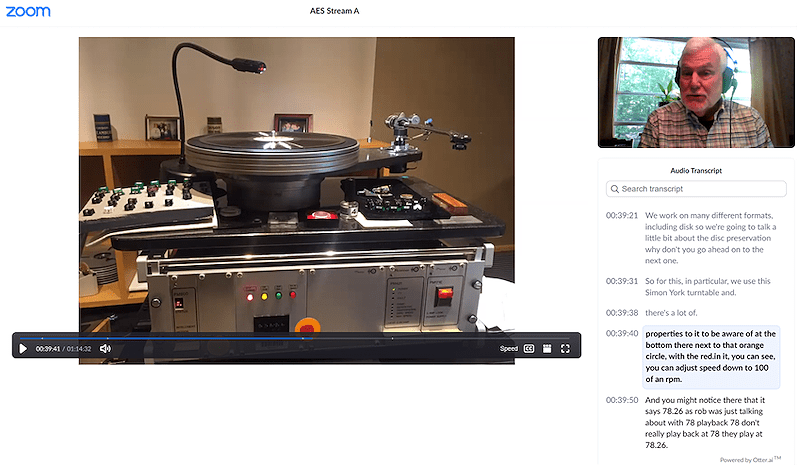

Brad McCoy and the Simon Yorke turntable. Courtesy of AES.

The Library of Congress uses Simon Yorke turntables exclusively for analog disc work.

For analog disc playback for restoration, preservation and archiving, the Simon Yorke turntable used by the Library of Congress offers incredibly precise specifications, with the ability to adjust speed to 1/100th of an rpm. McCoy noted that in order to replay 78 rpm records precisely for correct musical pitch, the speed must be at 78.26 rpm, for example.

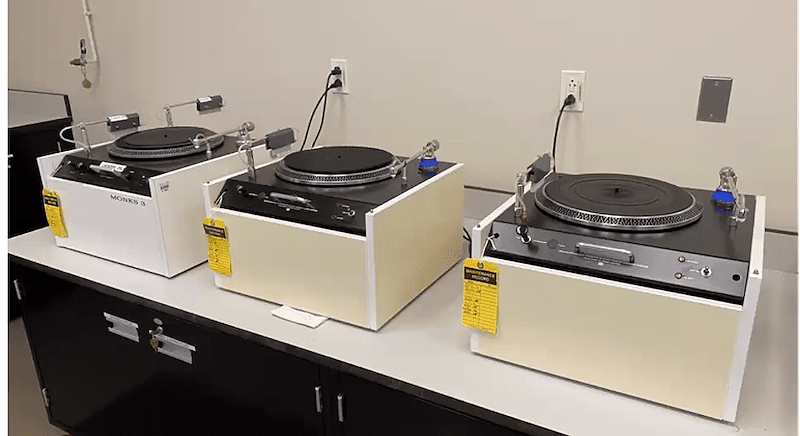

McCoy walked participants through the protocols he employs, which start with disc cleaning. McCoy uses a collection of Keith Monks disc cleaning machines for all source-material analog discs.

Keith Monks disc cleaners. Courtesy of AES.

To avoid contamination, three Keith Monks cleaners are each dedicated to cleaning only vinyl, lacquer, and shellac discs, respectively. The process employs a custom vacuum which literally sucks the grime out of the grooves.

McCoy concurred with Allingham that selecting the right stylus is crucial for optimum playback fidelity. However, McCoy and his colleagues, all engineering veterans, rely more on their ears than on measurement equipment, so a huge collection of stylus choices from Stanton, Shure, and other companies is available to them.

McCoy also noted that lacquer acetates can often come with protective coatings, such as aluminum, which, though noisy, can yield acceptable-to-good fidelity results when cleaned properly. He personally transferred some of the first ever 1933 Leadbelly prison recordings of “The Midnight Special” and “Goodnight Irene” by Alan Lomax from a bare aluminum disc, with exceptionally satisfying results.

From an Archiving 101 perspective, McCoy emphasized:

- Always save multiple copy backups in different locations.

- Preserve the original whenever possible in a temperature- and humidity-controlled storage place.

- Actively maintain both the preservation copy master and the original.

- Always make the best archival transfer possible and seek a preservation specialist if proper resources are unavailable.

McCoy sees archiving trickling down to other formats, such as wire recording and audio cassettes, and notes that new technologies and processes are always in development.

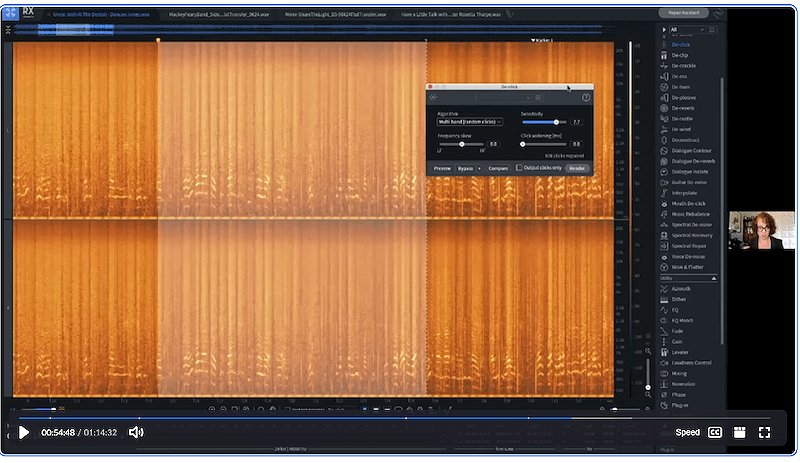

San Francisco-based engineer Jessica Thompson spoke about the specifics of vinyl source restoration and dealing with sonic problems related to vinyl, including how to deal with clicks and pops. She also pointed out some resources for useful software tools to help with the archiving process.

Thompson likens the work of vinyl restoration to archaeological excavation. As she puts it, “what we do is excavate a beautiful music recording that is covered under layers of vinyl dirt, grime, nicks and dings on the surface.”

When working on vinyl restorations, Thompson prefers using iZotope RX software (see my article, “Elvis is Back in the Building,” in Issue 127) for audio transfers, in its full spectrum mode with the de-click module. This method allows her to both see and hear the results of what she is doing.

Using examples from other restoration projects she had done, Thompson pointed out how certain instruments, like the harp, can become a nightmare, since iZotope RX has difficulty distinguishing between the sound of a harp pluck, and a click noise in the vinyl. In such cases she has to go into manual mode in order to individually remove the quieter clicks and pops without deleting the harp sounds as well.

Thompson’s strategy tips for click and pop removal include:

- Adjust the sensitivity in Auto mode for the maximum possible level, without affecting the audio.

- Use multiple passes to compare results.

- Treat intros, outros, and quiet passages differently than the bulk of the other content.

- Listen for ticks and thumps that might actually be part of the source material.

- Use Manual mode when needed to remove individual clicks and pops.

Although there was insufficient time to go into detail, Thompson also mentioned that iZotope RX was useful for removing groove distortion, sibilance, and rumble from a source recording.

iZotope RX screen sample from Jessica Thompson. Courtesy of AES.

McCoy applauded Thompson for her subtle and meticulous approach towards removing what was needed, without “sucking the life out of the recording.”

Wallaszkovits summarized the presentation by pointing out that engineers should trust their ears most of all when doing archiving and restoration work, rather than depending on looking at a computer screen. She concluded, “the best filter you have is the brain between your ears.”

The next part of our AES Europe Spring 2022 report will delve into presentations on new developments in loudspeakers and headphones.