In Part One (Issue 135), we reviewed the history of the affordable digital sound production technology that emerged in the 1980s and how some semi-pro and consumer equipment was used to create and record the sound for our 1988 independent feature film, The Source of Power. Given that this was the genesis era of a still-burgeoning digital technology, there was a learning curve to be overcome by music production studios using analog multi-track tape, film production houses using striped 35mm. mag and optical stock, and video studios using analog video tape. None of these camps had yet to make the leap to digital that is now ubiquitous in 2021. The story of the creation of our film continues here.

******

Now that writer/director Dan Godzich and I were armed with our compiled custom sound library for the movie, and had hired a post-production studio that understood what we needed to do and had worked with us to devise a protocol for doing it, we were ready to begin. The running time of the film was roughly 110 minutes, including credits. The order for creating the soundtrack would be to record dialog, Foley (sound effects that are added in post-production) and music cues. Once those were done, we would mix stereo tracks for each.

Dialog:

We had the original English-speaking actors on a schedule for ADR (automated dialog replacement) sessions of all their respective scenes and hired local New York actors and actresses for the smaller parts. (The movie was shot in a Spaghetti Western style, with dialog in English and French.) While it was exciting to have access to post-production studio Active Studio’s mic collection, including a vintage Neumann U47, we learned that finding complementary mics for the various actors and actresses required some trial and error. The Neumann, an AKG 414, and a Sennheiser 441 were the three mics that worked the best, and required the least amount of outboard processing to tweak their sounds.

After years of disparaging the poorly lip synced English dubbing of Chinese kung-fu films and Italian spaghetti westerns, I came away with a much greater respect for well-dubbed films, as the process was much more difficult than I had anticipated. The actors and actresses were all local New York talent that we knew through friends from independent film, theater, and comedy circles. Although some had never done any type of ADR before, they all did a creditable and professional job. Among them was a then-unknown comedian named John Leguizamo, who would go on to become a movie star a few years later.

While owners Steve Tjaden and Carl Farrugia had designed Active Studios as the ideal multi-format post-production studio facility that The Source of Power required, the one thing it lacked was a completely isolated vocal booth. Although the dynamic Sennheiser 441 mic had the greatest rejection of room sound and ambient reverberation, the condenser AKG 414 and tube Neumann U47 were very sensitive to reflected sounds, especially when actors raised their voices to match a character’s performance in a scene. Keeping dialogue as “dry” as possible was crucial, so that reverb and delay could be added later to match different dialogue parts into sounding like they were in the same location.

Necessity being the mother of invention, we finally rigged the foam-lined Calzone road case for our Korg DSS-1 sampling keyboard on a table behind the actors’ heads as an effective baffle to reduce the ambient noise. Subtle application of a Rocktron Hush II noise gate unit provided the rest of the “fix.” Of course, this was decades before software like the Izotope RX8, which can simply remove echoes and other sounds with a few clicks of a mouse, was invented.

Jean-Yves Denis in The Source of Power.

Sound Effects:

Triggering pre-recorded Foley sounds like footsteps, door closings and openings, car chases, the sound of people drinking water and so on from a keyboard to sync with image proved to be a much easier process than expected, and certainly less time-consuming than physically trying to match a video clip in real time like a professional Foley artist would. The use of an Eventide Harmonizer, Ursa Major and Lexicon delays, and various reverb units to create depth to the sounds saved hours of multiple overdubbing. We printed these added effects on an extra track or two for later mixdown. The DSS-1, an E-mu Emax synth and an Akai S900 sampler were used for creating loops of air conditioners, wind, pool water and other kinds of background location sounds when the sounds we recorded directly with the Sony PCM 501 ES digital audio processor were too short in duration.

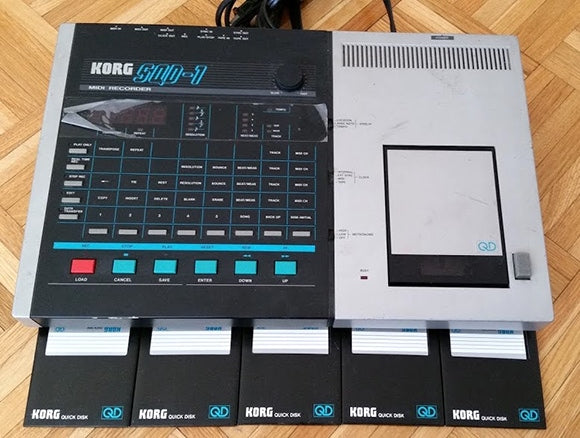

Korg DSS-1 digital synthesizer.

Music:

Lead actor Didier Hubert was also the lead singer and saxophonist for the French rock band Laser. I produced Laser’s album, Bienvenue, the year following the completion of principal photography on The Source of Power. We decided to use Didier’s song, “Pionniers” (Pioneers), for the film’s closing credits. Laser’s keyboardist, Jean-Pierre Duclay, had previously composed and recorded all of the film’s synthesizer soundtrack music cues during the Bienvenue sessions under Dan’s direction. We also MIDI-sequenced all of the parts in case we needed to change or augment any sounds during mixing. (By doing this, we could use the MIDI files to trigger any sound we chose via MIDI control – we weren’t limited to just using the pre-recorded sounds.)

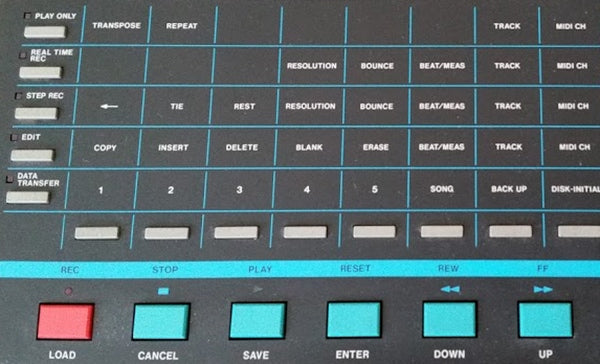

Recorded on 24-track analog and rough-mixed to a Sony PCM-F1 portable digital audio recorder in digital stereo in Tempe, Arizona, the soundtrack music was performed with Yamaha DX7II, Kurzweil K250 and Oberheim OB-8 synthesizers, with the MIDI-sequencing parts stored on a Korg SQD-1 unit with 2.8-inch floppy disks. As I recall, the digital stereo mixes worked for the most part, and we only needed to use the original multi-track tapes for the soundtrack music a handful of times. We replaced a few instrument sounds as needed, using samples from the Emax and Akai S900, as well as select programs from Oberheim Matrix 6R and Yamaha TX81Z rack units.

I wrote the title song, “The Source of Power,” with Dan and recorded all of the guitars, keyboards, and sequenced drums one afternoon at Active. Bass was provided by my former bandmate and session player Billy Asai. I recorded the lead vocals with my sister, Joanna Seetoo providing the harmony vocals. Click on the track below to play the song:

Mixing:

As I have mentioned in past articles, my audio engineering mentor was the late Grammy Award-winning engineer, Dennis Ferrante (John Lennon, Lou Reed, Aerosmith, Wynton Marsalis, Elvis Presley, Duke Ellington), who was a staff engineer with RCA/BMG studios at the time. [A posthumously published interview with Dennis Ferrante is in Copper issue 39 – Ed.],

Having had the past opportunity to sit in on some of Dennis’ sessions and assist him unofficially on occasion, I was familiar with work he had done on other films, such as Warren Beatty’s Reds. Dennis enjoyed the challenge of mixing the complete soundtrack for The Source of Power: dialogue, effects, and music – as long as we agreed to his rate, which was a no-brainer for us.

Dennis had been working on engineering and mixing orchestral music sessions for Spike Lee’s School Daze soundtrack and had expressed some frustration over the squabbling during sound mixing, with the dialogue, music and effects editors all lobbying Spike with their respective agendas. When I approached him about doing the sound mix for The Source of Power in its entirety in a familiar format (an audio mixing console used with state-of-the-art processing gear and analog multi-track tape) where he would have sole creative license and only have to deal with Dan and myself, he leaped at the opportunity.

Locating a 1-inch 8-track machine that could also take 14-inch reels proved to be a bit of a challenge, but Tjaden and Farrugia managed to track one down for rental and we were set to start mixing.

Sessions with Dennis were chock full of fascinating stories from his days working at the legendary Record Plant recording studio, interspersed with his great insights on the use of EQ, reverb, delay and panning to create a sense of space and depth in the stereo field. His experience with the Lucasfilm THX system had given him a boatload of ideas as to creating new ways to mix sounds in stereo, and Dennis relished the chance to put them to the test, as he intuitively knew what sound placements and balances would work best for a scene roughly 80 percent of the time.

One of Dennis’ funniest ideas was for a scene during a covert break-in of a hotel room. Shot from a low angle, he got the notion to make the squeaks of the actors’ shoes louder, the more they tried to be quiet. The scene subsequently elicited one of the bigger laughs during screenings.

Although he was hired for the film mix, Dennis also insisted on mixing my song, “The Source of Power,” after hearing the multi-track tape. Taking only a few hours, including his suggestion of my double-tracking the acoustic guitar part (cut right in the control room with a Neumann KM84 mic in under 20 minutes), the final mix exceeded anything I thought the song could sound like, and it actually went on to get radio airplay in France when the film later played at Cannes the following year. We were the fortunate beneficiaries of the “Ferrante magic” that graced such records as Lou Reed’s Berlin, Don McLean’s American Pie, and countless releases from John Lennon, Elvis Presley, Wynton Marsalis, and many others.

Once we finally completed mixing to the 1-inch 8-track tapes, we took the reels to Technicolor, who used the SMPTE time code to create synced mag tracks, which were then used to create an optical print.

While we were in the midst of creating the sound for The Source of Power, I don’t think Dan or I were fully aware of just how “crazy mad scientist”-like we must have seemed to our peers in the film, video and music production worlds, let alone to seasoned professionals. Dennis took me aside at one point and even exclaimed that he was amazed at how we pulled it off, and was even more shocked at why all of those pros charging big bucks never thought of it before.

A brief article about how we did the sound for the film was published in the December 1987 issue of Mix, but it was only two columns and since The Source of Power’s distribution was limited, the piece got little traction. Perhaps history will view it in a different light now with the missing details filled in.

Although distribution of The Source of Power was limited to only a few territories, moviegoers in France, like their adoration for Jerry Lewis and Clint Eastwood, have apparently developed a fondness for the film. It has a fan site that still exists today: http://jpaqman.free.fr/s_power/