Loading...

Issue 75

Gibson: Missed It By That Much

Believe it or not, it’s not over yet. Reports of Gibson Brands’ emergence from Chapter 11 bankruptcy were, as it turns out, premature. In Copper #72 we reported the news that thanks to agreements between the creditors, Gibson Brands would be emerging from bankruptcy all shiny and new, and far sooner than such things generally occur.

The creditors may have been satisfied by the terms, but as it turns out, Andrew Vara, the acting US Bankruptcy Trustee for this case in Region 3 of Fedearal Bankruptcy Court—-was not. In a 12-page motion entitled, “UNITED STATES TRUSTEE’S OBJECTION TO MOTION OF THE REORGANIZED DEBTORS FOR ENTRY OF ORDER (I) ISSUING A FINAL DECREE CLOSING CERTAIN CHAPTER 11 CASES AND GRANTING RELATED RELIEF; AND (II) AMENDING JOINT ADMINISTRATION ORDER TO DESIGNATE CHAPTER 11 CASE OF GUITAR LIQUIDATION CORPORATION, F/K/A CAKEWALK, INC., AS THE LEAD CASE (D.I. 1018)” (phew!), Vara laid out how the group of 12 creditors had cut corners, and had simply not followed the procedures of the Court.

In his conclusion, Vara states, “37. None of the Debtors’ cases are fully administered, and the Motion is premature. Moreover, the form of relief the Debtors seek, collapsing twelve separate cases into a single consolidated case for administration, is a form of substantive consolidation which would modify the Debtors’ confirmed and substantially consummated Plan. The final relief requested by the Debtors, a change of caption to reflect the closing of eleven of the twelve cases, is superfluous unless and until a particular case is actually fully administered and closed.

“38. The U.S. Trustee leaves the Debtors to their burden of proof on each element of relief requested, and reserves any and all rights, remedies, duties and obligations,

including all discovery rights.”

In brief, wrists have been slapped, attorneys chastised, and all and sundry have been ordered to go back and do it right this time. The tone of the motion shows thinly-veiled impatience and disgust not unlike that of a ninth grade English teacher who is fed up with having to explain footnote protocol yet again.

The full motion can be read here; an easier to follow summary is provided, as usual, by our friend Ted Green at Strata-gee.com.

Onward, into the Court’s calendar in 2019!

“When Did THEY Do THIS To US?”

The other day I had the opportunity to meet with a local journalist who anchors one of the local TV morning news programs. He had been trying to upgrade the audio system in his house and I had been offering suggestions via Twitter. During the course of our conversation, he happened to take a look at our website and came back and said “Hey I looked at your website and the stuff you make is pretty cool.” So, I invited him down for a visit, and he stopped by our offices and we gave him a tour and a demo.

We gave him the standard trade show newbie demo, where we play a track from an MP3 and then switched to the same track using a high resolution, uncompressed file of the song. After that we were standing around talking and, like most people who have never heard the difference, he was blown away. So, while we were talking, he looked at me and he asked me the question: “When did they do this to us?” Think about that for a second.

“When did THEY… do THIS… to US?”

Who exactly are they? —and what, exactly, did they do to us?

Now, this question came from a guy who is a well-regarded journalist and was recently recognized as one of the Top 5 journalists on social media. He’s also young and very technically savvy. This decline in music quality had happened entirely in front of him and he missed it. And he was completely shocked. And from the look on his face, not entirely happy either.

Now I admit that I look at this situation from my perspective within the industry, and that I’m not a completely unbiased observer. But this is how I explained it to him:

Back before the iPod, there were already personal music players and people were already ripping CDS but to be completely charitable, the whole experience sucked. And then Apple brought out the iPod.

The iPod allowed you to simply stick a CD into the CD reader of your computer where it would be ripped to your computer, the metadata would be imported into the library, and your music would be available for you to listen to on your computer or on your iPod. Apple also had the foresight to develop a decent user interface that made the entire experience reasonably simple.

Not entirely coincidentally, most laptops have crappy internal speakers or were connected to outboard speakers that also weren’t of a very high quality, and the iPod used earbuds where high audio quality wasn’t necessarily their first design consideration. In addition, the whole point of iTunes was to allow you to carry a vast amount of music with you but the compromise that you made was that the music was compressed and therefore of lower quality. That loss of quality wasn’t really an issue when you were playing it through lousy speakers or less than ideal earbuds. That also opened the door to headphone manufacturers who wanted to create better quality headphones which might improve the quality of the music. But that’s only tangentially relevant. The real point is that this whole paradigm shift was such a sea change that the average consumer readily accepted the loss of quality in exchange for a larger available library of music in their pocket.

Eventually, audiophiles realized that they could connect these computers to DACs and then connect those DACs to better quality audio systems, although at that point they were feeding their audio systems digital audio that didn’t sound very good. To this day, many audio purists will complain about the quality of digital music and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that they heard some of this early digital music and came to the unavoidable conclusion that digital sucks. And they see no real need to revisit that experience.

Over time, digitally-inclined audiophiles began to insist that higher quality uncompressed music be made available so that when played through these DACs they could enjoy an experience that was much more like the days when they listened to turntables and vinyl. Companies like HDTracks, Blue Coast Records, and even iTunes made higher quality tracks available, but it was at a slightly higher price.

Streaming services like Pandora came along and offered a radio-like experience which gave people the opportunity to discover new music although soon some customers wanted higher quality music, the ability to create playlists, and much richer catalogs of music of varying genres. Now you have services like Tidal and Spotify that have premium offerings that offer higher resolution and you have other services like Roon that provides a simple to operate user interface so that you don’t have to be a rocket scientist to listen to your music.

So, while audiophiles may have figured it out, the average user still exists in a world where their music is compressed thanks to services like Pandora, SiriusXM, and the free versions of Tidal and Spotify. They move through their life everyday listening to their music on crappy earbuds, headphones of varying quality, Bluetooth speakers, and if they’re really lucky systems like Sonos. Without even realizing it, they traded a world of quality for a world of convenience and never even noticed.

As manufacturers who work in this industry, we frequently have the opportunity to introduce somebody who’s never heard this kind of music, although perhaps what I really mean is this quality of music, and they have a palpable and visceral reaction. They’re shocked, they’re stunned, and in many cases, they’re pissed off. They react as though something was taken from them completely without their permission. And in truth, they’re not wrong.

We as manufacturers are doing a terrible job of exposing these potential customers to higher quality music sources and equipment. Memory, streaming speeds, and audio gear have gotten so cheap that customers can replicate the same experience they first had with their iPods over 15 years ago, but now with much higher quality. Instead of engaging these customers and pulling them in, we turn them off with childish arguments of “analog vs digital”, “vinyl vs CD”, and “my DAC technology is better than your DAC technology.”

We need to declare a truce on all these squabbles and start exposing customers to better quality music. It’s not too late to build a new and enthusiastic base, but we all need to do it together. I think this really is a case where a rising tide will lift all boats!

The 50 Best Albums of 2018

For me, 2018 was a blur, and seemed to pass faster than any other year before. Was it the politics? Was it work? Friends and Family? No idea. In all honesty, I had a hard time keeping up with all the new releases. Seemed like the kings and queens released the major stuff in 2017, which left a void for the up-and-comers to fill. This was refreshing, but took some effort to seek out the new jams. It’s a pretty eclectic list below, and I hope you’ll find some new favorites.

In terms of the music culture, I saw more acts coming to Colorado than ever before. It may be the city, the legalizations, or the fact that bands need to tour now more than ever. This list is important to me for two reasons: sharing “new” music with others and sharing the band’s website. Sure, you can stream with the best of them, but pay the dues and purchase a physical item directly from the band. Here’s an interesting fact: To date, Peter Frampton received a whopping $1,700 for 55 million streams of “Baby I Love Your Way”!

There is some phenomenal talent out there and in today’s time of instant-gratification, we seem to take the talent for granted. 2019 Resolution: consciously support the music you like.

Music is pretty special and we all need it, especially the musicians for their livelihood! Enjoy my list below, and feel free to post any artists that didn’t make the 2018 list.

In no particular order—and note that each artist name links to their website, and each album cover links to their music somewhere:

Top Dog

[There is no sexism intended by use of “man” in this piece. Luckily for the survival of humanity, insanely destructive competitive behavior is primarily, if not uniquely, a male trait. End of disclaimer—which may have done more harm than good—Ed.]

Man has always competed to be Top Dog. In the days when caves were homes, the guy with the biggest club was Top Dog. As we became more civilized, the fastest horse became the standard of manhood. When I was in High School, the Top Dog was the kid with the fastest car.

It was important to be Top Dog, so most of the guys worked after school and during summers to finance their ‘rides’— inspired by tunes from the Beach Boys and movies like Bullitt.

Stuart was raised in Britain where it’s tacky to be Top Dog, so he was indifferent to all of this. He spent his time reading books and playing with his slide rule—which he carried like a pistol in a leather holster on his belt. Then he inherited his aunt’s rusty, 1961 Ford Falcon 2 door sedan, a car which had all the sex appeal of Tiny Tim.

When he learned it was the lightest car in domestic production, he took a sudden interest in the car culture. He understood the physics of acceleration and the importance of mass. He made the car even lighter by eliminating such frivolities as the back seat, radio, bumpers, hubcaps, spare tire, and the even the chrome trim. Then he painted it black to hide the rust. It looked like a sewer rat.

With help from a friend of his fathers, he replaced the 6 cylinder engine with a salvaged 289 V-8, upgraded with a 4 barrel carburetor, aftermarket pipes, and carefully selected gearing. He debuted it on Labor Day at the hang-out for the local car culture, a deserted WW2 air strip nearby.

Everyone was there including all the jocks in their resplendent rides complete with accessory cheerleaders. Every muscle car of the era was represented, Mustangs, Camaros, Firebirds, Challengers, even an AMX. They chuckled when Stuart pulled up in his flat-black commuter special.

Before long, it was time to separate the men from the boys. The airstrip had only enough intact pavement to mark off an 1/8th mile drag strip. The jocks ripped through it with sound and fury adding another layer of black rubber to the tarmac. Stuart was allowed to compete only for comic relief. He was to be the closing joke of the show. His Falcon was paired with the biggest dog, a glistening, ’66 Caprice convertible with a supercharged 427 engine. It had a custom, candy apple red paint job with silver flake. Everyone laughed at the contrast.

The flag dropped, and the two were off. The Falcon came out of the chute like sling shot and immediately took a sizable lead. The 427 roared like a movie dinosaur, lighting up the tires which squealed and smoked and delighted the crowd. It built up speed like a 727, but not quick enough to overtake the Falcon before the finish line. Everyone was shocked, and agreed the outcome would have been different, had the course been longer.

But that was irrelevant: Stuart was the new Top Dog. Slide rule engineering had won the day. The guy in the 427 left the scene directly after the race with his tail between his legs. It was the most memorable event that strip had ever seen.

I was reminded of this story decades later at the home of a fellow audiophile. Like Stuart, Brad did his homework and created a purpose-built system. He researched audio engineering and built his own speakers. They had 15″ woofers, 10″ midbass drivers, large horns, and bullet-tweeters, all contained in large, home-made cabinets painted flat black. They were as tacky as Stuart’s car.

He bought well-used, professional amplifiers with tons of reserve power, an electronic crossover, and a turntable that was top of the line—a decade ago. Home-made acoustic panels were judiciously placed along the walls and ceiling.

Members of our audio club often visit one another’s homes to socialize and listen to music. One day a lawyer from North County named Hermann joined us. We’d been to his home several times. He was like the guy with the 427 Caprice. He had a large home with the latest, most fashionable, audio hardware — including enormous speakers painted automotive, candy apple red.

Brad started off by playing a cut from one of Hermann’s albums, Take 5, by Dave Brubeck. When the stylus dropped, so did Hermann’s jaw. I knew he was hearing more detail, dynamics, bandwidth, and sound-staging on this system than he’d ever heard at home. All his equipment had been selected from the Class A Recommended Components list at great expense — yet he was getting smoked by a guy in a flat black, ’61 Falcon. Then he did something I’ve never seen a lawyer do — he went silent. Shortly afterwards, Hermann took his records and went home.

Atypically, I didn’t hear from Hermann for several weeks. When we finally got together for lunch, he did what I expected and dreaded: he asked if I thought Brad’s system sounded better than his.

This was a no win situation for me. If I affirmed that it did, Hermann’s audio (and fiscal) acumen would come into question. If I didn’t, I’d be lying. So I copped out like a politician and responded to his question with more questions.

“Let’s talk about what we agree upon, Hermann. We both agree that better recordings result in superior sound, right?” He agreed.

“And we also agree that a better system results in superior sound, right?”

“Right.”

Now came a touchier question. “Do you remember that the speakers we liked most at the last CES weren’t the most expensive?”

“Correct!” Now we were getting somewhere.

“You’ve spent a lot of money on equipment, but you didn’t spend any time on research like Brad did.”

“I relied on the reviewers and sales personnel to tell me what’s best,” he responded.

“And maybe it is, as far as they are concerned. But their preferences, priorities, and acoustic spaces may be totally different from yours.”

“Right!” Hermann mused, “I noticed that Brad has a lot of sound panels on the walls.”

“You have a great house, with a lovely view, but the front wall of your living room is all glass, the back one is a marble fireplace, and the floors are tile. Acoustically, it’s a giant bathroom, Hermann.”

“I know, I know, I’ve thought about room treatment,” he said, “but I’m not prepared to compromise the view or the aesthetics of my living room. My wife would never allow it.”

“Right, but now that your son’s in college, you have a pretty large bedroom available that can be converted to a dedicated sound room.”

“But my wife has moved her sewing stuff in there.”

“So make her a deal: in return for removing all your audio clutter from the living room, you get the bedroom.”

Hermann’s face lit up. “That might be an easy deal to negotiate!” he responded.

We spent hours drawing plans on a napkin to convert his son’s bedroom to a sound room. Hermann was excited.

A couple of weeks later, Hermann called to advise that he’d just taken delivery of 8 diffusive and 8 diffractive acoustic panels. We moved his speakers and the panels around the room measuring the results with my frequency spectrum analyzer. To eliminate a 12 db. room mode at 60 Hertz, it was necessary to add an equalizer— which I’d brought with me in anticipation of such a problem.

The difference was startling. The smaller room dramatically improved the bass and dynamics, and the wall treatments notably enhanced the midrange and highs. Hermann excitedly said that for less than what he’d recently spent on cable upgrades, he was getting an entire system upgrade.

But his system still doesn’t sound as much like live music as Brads. For that, he needs different speakers.

It takes more than candy apple paint to be Top Dog.

Joni Mitchell

In 1943, Alberta, Canada released a musical wood sprite into the world who came to be known as Joni Mitchell. A polio survivor whose damaged fingers made her get creative in learning the guitar, Mitchell started life as a determined original; at age 75, she can still be described that way.

She scraped by, working at a coffee shop and singing in hootenannies in Toronto until her songwriting took her to the U.S. There she made some big song sales, including the Judy Collins hit “Both Sides, Now.”

Although she’d been performing paid gigs since 1962, she had to wait until 1968 to launch her solo recording career with the album Song to a Seagull on Reprise Records. The producer assigned to this project was none other than David Crosby. He did an infamously lousy job, capturing too much ambient noise and hiss; when it was removed post-production, it also took some high frequencies off everything. After that experience, it’s easy to understand why Mitchell took control of her own studio production thereafter.

The first album contains almost entirely her own playing – guitar and piano – on every song, with the exception of Stephen Stills contributing bass on the jaunty “Night in the City.” That number is a great way to kick off this retrospective of Mitchell’s songs and singing. American folk historians like to point out that she sang lower starting in the mid-seventies, but this track proves she had the high-powered contralto end of her range at the ready from the start.

Critics started to take notice with the second album, the following year. Clouds gets its title from Mitchell’s own recording of “Both Sides, Now,” which ends Side 2. One forgotten song that deserves attention is “That Song about the Midway,” a wonderful example of Mitchell’s unusual approach to crafting melodies, using large leaps from head voice to chest voice. And then there’s the wonderful, unique imagery of her lyrics: “You stood out like a ruby in a black man’s ear.”

Much as I’d love to stop by every one of the 17 studio albums, it just isn’t practical. But I want to be sure to spend a little time on For the Roses, which tends to get lost between the two bigger commercial successes, Blue (1971) and Court and Spark (1974). For the Roses is largely inspired by Mitchell’s brief, tempestuous relationship with James Taylor, which had just ended.

She shows a different side of her songwriting, singing, guitar playing, and sound production choices in the song “Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire.” The vocals are acoustically diffused over layers of percussive acoustic guitar. James Burton wanders through eventually with a high lonesome line on electric guitar. One of the many interesting aspects of this song is its meter: lyric and melodic ideas keep starting up where you don’t expect them rhythmically.

While Court and Spark marks a decision on Mitchell’s part to become more serious about jazz, the following album, The Hissing of Summer Lawns (1975), finds her doubling down on that goal by focusing her singing range to what might be described as her “natural” and more powerful contralto.

“Jungle Line” is an intriguing work with some world-music cred before folks like Peter Gabriel and Paul Simon made it cool. The song is built on a track of “warrior drums” taped in field recordings in Burundi. Mitchell, who came very close to a career as a painter (her art has appeared on more than one of her album covers), writes an analysis of “primitivist” painter Henri Rousseau in terms of working-class life in the modern city.

The ʼ70s continued with Hejira (1976), Don Juan’s Reckless Daughter (1977), and Mingus (1979); the last was a memorial to her jazz hero and close friend Charles Mingus. Five of the 11 tracks are “raps,” as she calls them: the great man himself, singing little ditties, with Mitchell joining him an octave above. It’s quite a touching way of memorializing their musical friendship.

The albums kept on coming every two or three years. I have a soft spot for Chalk Mark in a Rain Storm (1988), if for no other reason than its roster of collaborations. There are guest appearances by Don Henley, Peter Gabriel, and Willie Nelson. On “Dancin’ Clown,” the vocal cameos are by Tom Petty and Billy Idol, with Thomas Dolby of all people on marimba! The song is a sort of a takedown of bouncy, sugary ʼ80s pop.

Mitchell never let up on the quality of her songwriting and studio creativity. She won a Grammy for Best Pop Album for her 1994 record Turbulent Indigo. One important contributor to its success is soprano sax player Wayne Shorter, another jazz great whom Mitchell had befriended back in the ʼ70s when she was trying to stretch and strengthen her chops in that genre. Here’s Shorter helping out on the title track, “Turbulent Indigo,” which snidely offers guidance on how to mass-produce copycat artists who’ve never had to suffer.

Even after announcing her retirement from music in 2002 (her album from that year, Travelogue, contains new orchestrations of old songs), Mitchell couldn’t keep her muse quiet. The Iraq War was her impetus to write the Shine album in 2007, her first collection of new songs in a decade. It also includes a new version of her 1970 hit “Big Yellow Taxi.”

Perspective changes as one ages, and so this album – maybe her last – ends with the stoical Victorian advice that Rudyard Kipling gave his son in the 1895 poem “IF,” which might have seemed a bit prudish and careful to her younger self. Mitchell uses excerpts equaling about half of Kipling’s text, slightly rewritten here and there to make the language less formal.

The tone is soft jazz, and Mitchell’s voice is roughened, her vibrato widened, giving her the status of hard-won veteran of the music wars, like an old jazz singer. She’s persevered through it all and has earned our respect for sure.

Fairchild, Part 1

I truly enjoy the research involved in these pieces, refreshing faded memories, absorbing facts overlooked or misunderstood in my youth, and especially—ending up somewhere completely unexpected. That’s how I came to look into Fairchild, while writing in Copper #66 about phono cartridges and Joe Grado, whose company is still around in Brooklyn. Grado began in audio by building cartridges for Fairchilld; to quote myself, “Grado was an opera singer, watchmaker and inventor; he was also a friend of hi-fi pioneer Saul Marantz, who introduced Grado to Sherman Fairchild.

“Fairchild was a multimillionaire serial entrepreneur who founded dozens of companies in many fields including aircraft, aerial photography, and the Fairchild Recording Equipment Corporation, devoted to products for professional and broadcast audio. The Recording Equipment Corporation, based in Long Island City, also dabbled in home hi-fi—and that’s where Grado went.”

It’s not often that one encounters a “multimillionaire serial entrepreneur” while researching audio. In fact, I think I can count the ones I’ve come across on one finger—namely, Sherman Mills Fairchild.

So who was he?

Sherman Mills Fairchild was born April 7, 1896 in Oneonta, New York, the child of George Winthrop Fairchild and Josephine Mills Sherman Fairchild. At the time of his son’s birth, Father Fairchild was involved in the weekly newspaper, the Oneonta Herald, and was also a partner in Bundy Manufacturing, a maker of timeclocks. In 1907, Fairchild was elected to the House of Representatives, where he served until 1919. A few years later, in 1911, Fairchild became president of a newly-formed company with the lengthy name of The Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company; he was also a delegate to the 1912 and 1916 Republican National conventions.

In short, George Fairchild was both a man of means, and a man of influence. In 1924, the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company was renamed International Business Machines—yes, IBM. Fairchild was the company’s Chairman and largest single shareholder at the time of his death on December 31st, 1924. His wife had passed away in January of that same year, and Sherman was an only child. At age 28, Sherman Fairchild was left as the largest single shareholder in IBM, which would be true until his death in 1971.

But we’ve gotten ahead of ourselves, and skipped Sherman’s early life.

By all accounts, Sherman was extremely bright, and his family’s position allowed him to have the best education possible: in 1915, he headed to Harvard. During his freshman year there, Fairchild developed a camera with synchronized shutter and flash—an invention that would change his life, and the world. Fairchild came down with pneumonia, and moved to the drier climes of Arizona, where he attended the University of Arizona and increased his involvement in photography.

By 1917, Fairchild had developed an aerial camera which contained the shutter within the lens itself, designed to overcome the shutter lag that caused blurring in most aerial photographs. Fairchild and his father—the Congressman— secured a contract to develop the aerial camera for the military, along with $7,000 in funding. The actual developmental costs were $40,000; the elder Fairchild paid the difference.

As the World War drew to a close, the military’s need for the aerial camera diminished. Undeterred, Fairchild established the Fairchild Aerial Camera Corporation in 1920 to produce the camera, and sold 20 to the Army. Fairchild took a camera aloft in a Fokker biplane to produce aerial images of Manhattan, and in 1921, Fairchild Aerial Surveys was formed to commercialize aerial mapping and surveying. Newark, New Jersey was the first major city completely mapped by means of aerial photography. By 1923, a Canadian branch, Fairchild Aerial Surveys of Canada, had been founded to capitalize upon the need to map the vast uncharted areas of that country.

Following his father’s death, Fairchild was appointed as a director of IBM, and also joined the board of an air transport company owned by Juan Trippe, founder of Pan American Airways. Characteristically, in 1925 he also founded Fairchild Aviation Corporation as a holding company to manage companies producing aircraft engines and airframes designed specifically for aerial photography, having found surplus biplanes inadequate for that purpose. Fairchild never shied away from starting new business entities to develop his ideas; unlike most serial entrepreneurs, he was successful at—well, being successful. Few, if any, of his dozens of ventures failed.

Within the next few years, Fairchild monoplanes would become known as the most advanced planes in the air, used to fly Lindbergh on his nationwide tour, and utilized by Commander Richard Byrd in his first flights over Antarctica. The versatility and cargo capacity of Fairchild monoplanes help save Trippe’s struggling Pan Am by enabling the airline to become a major carrier of air mail. Within a span of months, production of the FC-1 mapping airship and its production derivative FC-2 made Fairchild Aviation the second largest producer of aircraft in the world.

The elegantly simple FC-2.

In the turbulent year 1929, Fairchild Aviation acquired controlling interest in Kreider-Reisner Aircraft, and buit new manufacturing facilities in Hagerstown, Maryland, where eventually, all aircraft production would be consolidated. In the years that followed, acquisitions, divestitures, and repurchases of aircraft companies would make the company’s many divisions hard to track.

And yet, photography remained at the heart of everything. Fairchild developed products to improve all aspects of image production, processing, and reproduction, from filmholders, multiple generations of both still and motion picture cameras, processing frames and tanks, contact printers, projectors, and so on. Perhaps spurred on by the rapid growth of talking films, in 1931, the Fairchild Recording Equipment Corporation was founded in Whitestone, New York, with the goal of producing sound recordings of quality equal to Fairchild’s motion pictures.

We’ll pick up the story of Fairchild in the audio world in the next issue of Copper.

Berlin Stories

KaDeWe

“How can you stand to be here after all that happened to your family?” Her name was Anna and she lived in East Berlin. I met her at the champagne bar in the food level of the KaDeWe department store in West Berlin. The champagne bar is a great place to meet people. After a few glasses of bubbly, everyone is your friend. She had been coming to this bar on the same date every year since the wall came down in 1989. This bar was her first taste of true freedom after a lifetime of communist rule. She had been married. Her husband had died a year before and she felt compelled to carry on this tradition. Perhaps it was the champagne, or just the anonymity, but she poured out her heart to me.

Tomorrow would be her father’s 56th birthday and she felt obligated to visit him. She never liked her father, but she recently discovered that he had been a spy for the Staatssicherheitsdienst, SSD (more commonly known as the Stasi), the infamous East German State security service, an internal spy agency reviled in East Germany before the wall came down. What bothered her most was that many years ago, her husband had been interrogated by the Stasi for having western leanings. He was summoned numerous times for questioning and, even though they found nothing to incriminate him, the experience was traumatizing for both of them. She now suspected her father of pointing the finger at her husband. He had never liked him and disapproved of their marriage. She asked me what she should do.

“What would happen if you never see your father again?” I asked.

She said she would be ecstatic.

I suggested the following, “Go see your father tomorrow and tell him this. ‘I know what you’ve done and I’ll never forgive you as long as I live.’ Then turn around and walk away.”

She thought that this was great idea, but I doubted that she would carry it out.

She then asked me why I was in Berlin, and I told her of my family’s history and that I was in the process of retrieving family property stolen by the Nazis. She couldn’t accept the fact that I had come to Berlin and harbored no hatred for the place. What she didn’t know was that I felt comfortable in Berlin because I had discovered something about my father; I had always thought of him as a German, but I found out that he was a Berliner and his manner of speech and mannerisms, not to mention his sense of humor, were specifically from that town. After all that had happened to my family, I felt at home there.

We closed out the bar at some late hour, but to our surprise, we also had closed down the store and had to walk down six flights on the frozen escalators to the exit. Empty department stores are most eerie. I walked her to the tram, kissed her on the cheek, and strolled back to my hotel through the gloom of the evening.

Streusand

One evening, my lawyer said that another client of his was joining us for dinner. I didn’t mind, as I enjoyed dining with Dieter. His taste in food and wine was excellent, and over the years of my dealings with him, we had become good friends. We went to the restaurant and were presently joined by Mr. Streusand. He was in his sixties and rather sour looking. I was planning a celebration, as I had recently acquired the deed to a property owned by my grandmother and was going to meet with a realtor the next day to try to sell it. I was on my second drink when Streusand arrived, and his demeanor immediately sobered me up. Some people bring joy to an evening, others suck up all the oxygen. He lived in Israel and was having problems with his daughter. He said all she ever asked for was money, and that she gave him no respect or love in return. He droned on about how bad business was, etc. This wasn’t the evening I had planned.

To try and changed the subject, I asked him, “Streusand, that’s a unusual name. Are you related to Barbara Streisand?”

He said, “Yes, my grandfather and her grandfather were brothers. One came to Palestine, the other to the USA.”

“Have you met her?” I asked.

“No!”

“Why not?”

“She would think I wanted something from her.”

“Why would she think that? Maybe she would be interested in meeting new members of her family,” I replied.

“I wouldn’t know how to contact her.”

I said, “I’m sure I could find out who her publicist is, and you could write a letter to him to pass on to her.”

For the first time since we met, he brightened.

“Really?”

“Sure, just let me know, and I’ll see what I can do.”

That conversation was the only enjoyable part of the evening. No matter how much I drank, I was cold stone sober all night. A few days later, my lawyer rang me to tell me that Streusand had returned to Tel Aviv and committed suicide. I often thought of writing this down and sending it to Ms. Streisand, but I never did.

Lichtenberg

The deed to my grandmother’s block of flats in Lichtenberg, adjoining the railroad station, had a swastika stamped on it in 1941 when my grandmother defaulted on the mortgage after the family had fled to the Gironde in France. There was another stamp from 1953, stating that the property was now owned by the GDR, The German Democrat Republic.

Lichtenberg was a run-down suburb of East Berlin. The property on Weitlingstrasse consisted of around 20 apartments, with three or four shops below. At some point in the seventies, the building had done renovations and under some quirk of German law, I had to settle the mortgage before getting clear title. It wasn’t a significant amount of money, but it really pissed me off. As I had no alternative, I arranged a bridging loan with a local bank. I met with the realtor. He told me the following.

“Lichtenberg was a poor suburb, and was also poor before the war.”

This I knew.

He continued, “Also, the market has recently dropped.”

This, I also knew. It was the mid-nineties and the initial euphoria and speculation over the unification of East and West Germany had faded.

“Then, there is the added problem.”

“What added problem?” I asked.

“This is where the Neo Nazis live in Berlin.”

I sold it for a pittance and never returned to Lichtenberg.

You Know It Ain’t Easy, Part 1

Montreal, 1969

Over the last year or so, I have run across 2 people with incredible stories about how they planned ways to meet John & Yoko, and managed to actually do it. One story took place in 1969, and one in 1980.

Both stories showed a side of J&Y that, while on one hand showed perhaps surprising empathy, also showed an almost shocking hippie-like naivete.

Montreal, Canada 1969

This first story is about legendary Canadian radio talk show host Tommy Schnurmacher [Not a typo—I checked—Ed.], who, at the age of 18, wanted to get John Lennon’s autograph.

On May 26th, 1969, John, Yoko & Yoko’s daughter Kyoko and a small entourage which included their press agent Derek Taylor, booked themselves into the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal, Canada to commence their “Bed-In for Peace”. On June 1st, they recorded the song, “Give Peace a Chance”, live from their bedroom in the hotel and surrounded by various characters, the song. The song was still being written, right up to the time that it was recorded.

Much has been written about that visit, all the personalities who showed up to pay respects to John & Yoko (comedians Tommy Smothers & Dick Gregory, LSD guru Dr. Timothy Leary, pop star Petula Clark, & Li’l Abner cartoonist Al Capp) and the recording of the song. What you probably don’t know, however, is this sidebar to the entire 8 day experience.

The fact that J&Y chose Montreal was broadcast over a local radio station, and an 18 year old high school student, Tommy Schnurmacher, along with a female friend, decided that they wanted to get John’s autograph. To make it easier to get to John, Tommy planned on showing up as a member of the press (the high school press, you understand), with a tape recorder and “interview” John. That, he felt, was sure to lead to an autograph.

When Tommy and friend arrived at the hotel they were shocked that there didn’t seem to be any security in the lobby. They quickly learned that J&Y were in suite 1738 (17th floor), got in the elevator, went up to 18 so as not to create a suspicion and walked down one flight to the 17th floor. Down the hall they saw a small group of people outside the room. Tommy, knowing that Kyoko was there, brought a box of crayons. When they walked into the hotel room, a security guard in the room started to question why Tommy was there but Kyoko saw the crayons and wanted to use them— so Tommy said that if he was thrown out he would take the crayons. Yoko interceded, Tommy gave the crayons to Kyoko, and Yoko asked if they wanted to meet John, who was in the bedroom.

Tommy was told that he could not ask John question about the Beatles. The questions had to center around the Bed in and J&Y’s quest to bring peace to the planet. At some point Yoko asked why he had crayons. Tommy said that he had a sister Kyoko’s age and he was going back to his house to see her. Yoko asked if they wanted to take Kyoko to their house to meet Tommy’s sister. Tommy, stunned, said sure and Yoko handed Kyoko over to Tommy and his friend. They took Kyoko back to Tommy’s house to meet his sister and fed Kyoko as well.

Thus began a daily ritual which went on for 7 straight days!

Tommy and friend would come to the hotel, Yoko would give them Kyoko, off they would go and bring Kyoko back later in the afternoon. Yoko never asked for any ID. Never even asked for their last names!

The temptation to ask Kyoko questions about the Beatles and especially “Uncle Paul” (Paul McCartney) was strong. In the end it was decided that if they did and Kyoko told either John or her mother, that circle of trust would probably be broken—so they didn’t.

On day 8, Tommy again went back to the hotel only to find that everyone had checked out. They left behind items specifically for Tommy, however. 2 signed autographed albums (personally signed to Tommy and his friend) as well as signed publicity photos and $150.00 to cover their “nanny time” with Kyoko.

As they were about to leave the hotel room still being cleared out by someone probably with the record label, Tommy’s friend found, on the floor, the hand written lyrics to “Give Peace a Chance” that were left behind.

She took them!

That piece of paper with the hand written lyrics were sold many years later at an auction for nearly $300,000.00!

The ‘friend’ did not share that windfall with Tommy, which remains a very sore subject (and rightly so).

I asked Tommy if he ever did write up the “Lennon interview” for the school paper. The answer was that even though the interview was recorded he never did write it. Moreover, the tape disintegrated after years of storage.

I ended my interview with Tommy by asking him 2 questions:

1. Did his friends believe the story? He said that most of them didn’t at the time.

2. Did you understand their (John & Yoko’s) astounding naivety and “trust”?

“Looking back, the hippie naivete they showed was unreal, and the fact that they never even asked us for ID was pretty amazing”.

Luckily John & Yoko trusted the right person. Thank you Tommy!

Part 2, in Copper #76.

The Volume Of A Pizza

Numbers, and the mathematics that describe them, can help you with many interesting things, including the volume of a pizza.

There are some wonderful surprises hidden in plain old numbers. Things that can delight you because you can’t imagine how such simple things could be possible. To many, the temptation is to read things into them that can’t possibly be true. Other times, even professional mathematicians just sit back and shake their heads in amazement. A perfect example of the latter would be the Mandelbrot Set, an extraordinary pattern generator based upon a single, absurdly simple mathematical equation. Mathematicians continue to study the Mandelbrot Set, and are always coming up with complicated new analyses to explain just one single feature, but none come close to shedding light on the extraordinary level of infinitely repeating – yet always subtly varying – swirling patterns for which the Set is justifiably famous.

The video below zooms deeply into a random part of the Mandelbrot Set. Try to watch it full screen. The entire video is 16 minutes long, but by the 2’45” mark we have zoomed in so far that the complete Mandelbrot Set would occupy the size of the entire observable universe. By the end of the video, the size of the complete Set would so large as to be beyond any meaningful ability to describe it. Yet every last micro detail you see in the entire video is generated by just one trivial equation. You can enjoy it in phenomenal video resolutions as well…up to 2160p60.

Here’s a much simpler piece of mathematical trivia. The square of a Prime number is always a multiple of 24, plus one. Think about that for a moment. Can that be true? Is life really as simple as that? A few moments spent on a calculator readily shows that it holds good for every Prime number your calculator can handle. But what on earth is so special about 24? Why on earth should Prime numbers have that intriguing property? Mathematics holds the simple answer in its hands.

Here it is. If P is a Prime number, and P2 is 1 plus a multiple of 24, then it follows that P2–1 would need to be a multiple of 24. We can simplify this by observing that:

P2 – 1 = (P–1)(P+1)

Therefore, our question instead becomes: Is the product of (P–1) and (P+1) always a multiple of 24?

- First, we observe that (P–1), P, and (P+1) form a run of three consecutive numbers. Therefore, one of them must be a multiple of 3. Obviously that can’t be P, since it is Prime. So one of either (P–1) or (P+1) must be a multiple of 3.

- Next, since P is Prime, it must be odd, so both (P–1) and (P+1) must both be even. With any two consecutive even numbers, one must be a factor of 2 and the other a factor of 4.

So (P–1) and (P+1) between them must include the factors 2, 3, and 4, whose product is 24. Therefore, the product of (P–1) and (P+1) is always a multiple of 24.

Less intriguing, but just plain old cool, is an observation involving factorials. The factorial of a number (it only applies to integers) is obtained by taking the number and multiplying it by every integer less than itself. So, the factorial of 4 (denoted by placing an exclamation point after the number) is 4! = 4x3x2x1, which is 24. (There’s that number again!). Factorials arise most often when calculating probabilities and combinations. For example, the number of ways to order a deck of cards is 52! which is a seriously huge number. Therefore, if you perform a perfect shuffle on a deck of cards, it is virtually guaranteed that the exact card sequence you’ll get will have never previously occurred in the history of the universe, and furthermore will probably never occur ever again! And my cool observation regarding factorials is this…the number of seconds in 6 weeks is exactly 10!

Let’s check that one out. There are 60 seconds in a minute, 60 minutes in an hour, 24 hours in a day, and 7 days in a week. So, the number of seconds in 6 weeks is:

60 x 60 x 24 x 7 x 6

I can expand one of the 60’s into (10 x 3 x 2) and the other into (5 x 4 x 3). I can also expand the 24 into (3 x 8). So, the number of seconds in a week becomes:

(10 x 3 x 2) x (5 x 4 x 3) x (3 x 8) x 7 x 6

You’ll see there are three 3’s in there, so all I have to do is take two of them and multiply them together, which turns them into a 9:

(10 x 3 x 2) x (5 x 4) x (9 x 8) x 7 x 6

This contains one each of all the numbers from one to ten, multiplied together, which is 10 factorial. Therefore, there are 10! seconds in 6 weeks.

OK, so that was also a little trivial. But here’s something you are flat out not going to believe. What do you get if you add up all of the positive integers? Infinity, right? We’re talking about:

1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 +6 + 7 + 8 + + +…

…and so, every number you add to the tally only makes the result exponentially bigger, all the way to infinity. But what would you think if I told you that the answer is actually minus one twelfth? Yep, all the positive integers add up together to ‑1/12. A totally absurd proposition, I agree, but quite surprisingly, this answer forms the basis for some of the most important problems in advanced theoretical physics, including String Theory. It was first noted by a famous Indian mathematical savant, Srinivasa Ramanujan, in 1913. I should observe that many mathematicians will point out, quite rightly, that you are dealing with infinities here, and that while the result may be perfectly correct in one context, it may equally be totally incorrect in another. But I thought it was worth throwing in there, even though I’m not going to offer up the proof (since it is a bit too elaborate, although not in fact all that challenging).

While mathematics is arguably the ultimate precise science, the one with the least possible room for ambiguities and dispute, it has nonetheless had to deal with ambiguities and disputes since time immemorial. Back in about 520BC, the school of Pythagoras believed, and taught, that everything could be explained using numbers. And by numbers, they meant integers. Of course, they knew that quantities existed between adjacent whole numbers, but they insisted that these could all be represented as fractions, or ratios between pairs of integers. However, problem began to emerge when they established the famous theory of Pythagoras, that for a right-angled triangle, the lengths of the three sides were governed by the relationship:

A2 + B2 = C2

The question was, if A = 1 and B = 1 then what is C? It is a quantity which when multiplied by itself gives the result 2, and which we call √2. A scholar named Hippasus of Metapontum was reputedly the first to recognize a fundamental problem which this forced them to face. Clearly, the answer was a number between 1 and 2, and so (according to Pythagoras) had to be a ratio between two integers:

√2 = M/N

M and N were both simplified by cancelling out any common factors. Therefore, it is clear that at least one of M and N must be odd (otherwise there would be a common factor of 2 that could be cancelled out). However, if we then consider that M2/N2 = 2, this would require that both M and N must both be even. This obvious contradiction means that there are no such integers M and N that could satisfy the criterion. There was no possible ‘rational’ number that could represent the quantity √2. For this apparent heresy, Hippasus was thrown from a boat and drowned.

Some corners of mathematics receive what appears to be a disproportionate amount of detailed attention, and at the head of that line is undoubtedly π. People have devoted remarkable energies to evaluating π to extraordinary degrees of precision. When I was at university in the 1970’s (studying Physics), one of the professors in our math department claimed to have been the first to calculate π to a million decimal places. The result, printed on computer paper, occupied a wall in his office. Today, the record stands at 22,459,157,718,361 decimal places, and represents not so much the limits of capability, as the limits of patience, combined with the desire for a certain ‘coolness factor’ (that number of decimal places was carefully chosen for its quirky significance, appreciated only by mathematicians). Sufficient computer paper does not exist to print it out!

The algorithm currently used to enumerate π, Alexander Yee’s “y-cruncher”, was originally developed as a tool to torture-test CPUs. It is in the public domain, and has been the only show on the road since 2010. It runs on readily available, although carefully specialized, PC hardware. Here is a question for you to ponder…how much hard disk space would you need to store a 22,459,157,718,361-digit number? BTW, aside from “y-cruncher” there is an algorithm available which can quickly and efficiently calculate just the Nth digit of π, for any value of N, if such a thing is of value to anyone. Seems incredible to me, but there you are. I guess you could assign part of your evening to calculating the 22,459,157,718,362nd digit, if you were of a mind to do so.

People have studied π to assess whether there are any unusual features in the distribution of digits in π, and to a remarkable degree the distribution is indeed totally random. Not only that, but auto-correlation tests show that second- to fifth-order distribution features are also all totally random. This has also been extended to representations of π in bases other than 10, with the same result. That the digits of π pass every test thrown at them for randomness puzzles some people. There is a philosophical point in play here…the dichotomy between what appears to be a truly random process, yet one which arises from a fundamentally structured quantity. But there is also a lunatic-fringe element who are determined to uncover a hidden message from some kind of higher power. Good luck with that…but if they do discover such a message, I’ll be careful to re-designate them as prophets.

Oh, and the volume of a pizza? Well, if the radius of the pizza is Z, and its thickness is A, then its volume is given by:

Pi*Z*Z*A

2018 Was Really Something

Over more decades in audio than I care to dwell upon, I’ve attended concerts and demos that assaulted not just my ears but my intellect and my emotional stability. Somehow those occasions have all-too-often involved people I like, folks I’m trying to encourage, or honest to God friends. Inevitably, the dreaded query comes:

“What did you think, Bill?”

I try to keep the friends friends, by being honest—tempered with as much gentle enthusiasm as I can muster out of my dark old soul. The other groups?

I fall back on several similar responses, which really say nothing, but allow the eager questioner to hear what they want:

The first and simplest involves nodding and looking pensive while muttering, “…interesting…interesting.” That one is the closest to being honest: I do find massive failures of artistic intent and violations of the laws of God, man, decency, and physics interesting….in the same way that I find unexpected entanglement in a massive cobweb interesting.

As long as I can breathe normally and suppress the urge to scream or panic, all is well. Easy-peasy. Next:

“Wow (shaking head)—I have never heard anything like that.”

Or its close cousin, which also involves shaking my head—somehow that indicates sincerity. Remember Bart Simpson’s axiom, “Once you learn to fake sincerity, the rest is easy.” So:

“(Shaking head in silent reverence) now that-—that was really something.”

I don’t know how it was for you—but for me, 2018 was really something. The year wasn’t as catastrophically destructive to the music world as the last few years have been, with dozens of top-tier talents dead and gone—but 2018 did take Aretha, Montserrat, and Aznavour, along with a lot of important musicians who never quite reached the one-name level of fame. Dolores O’Riordan, Roy Clark, Marty Balin, Nancy Wilson, Tony Joe White, and Hugh Masekala—all were immediately recognizable, once you’d heard them.

There are a zillion lists out there like this one from the NYT—but I’m not going to pick out notables, month by month–it’s too damned depressing. The good news is that a lot of these folks had some serious age on them—101 for Nancy Sinatra (the wife and mom one, not her “Boots” daughter—although, HOLY CRAP, “Boots” is 78??)? 94 for Aznavour? And other than O’Riordan—God rest her troubled soul—I’m not aware of a cluster of well-known suicides, as we’ve seen in recent years. –Oh crap: Avicii. Never mind.

Outside of music, there were deaths of a number of notables who shaped the world for me and millions of others: Stan Lee. Paul Allen. Stephen Hawking. Pappy Bush. Not saying I understood, liked, or respected all of them, but they did change the world, for good or ill. And in the arts and the business world, a number of unique souls moved on.

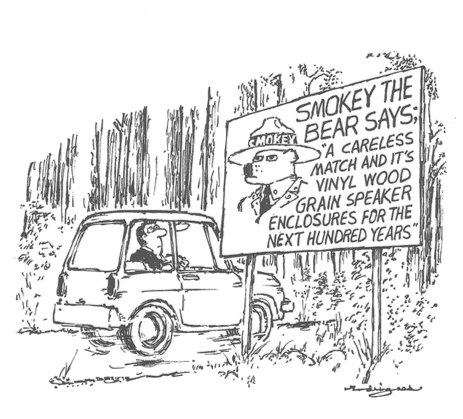

This, combined with the chaos of the world in general (including aesthetic insults as seen in the header pic), contributed to making 2018 really something.

And yet, and yet: personally, it was a year in which I traveled once again to Munich, and to South America with my son. My daughter was married, and now, she and her husband are expecting their first child, my first grandchild. I have a loving girlfriend, work in a field with great people doing interesting and challenging things. I live in a beautiful place. And oh: I have two faithful, albeit insane, canine companions. Life is good. Really.

Maybe in 2019 I’ll have to change the name of this column. Somehow. “The Audio Softy” doesn’t have the same ring to it….

The Revenge of The White Album

By now, you know whether The White Album re-issue is for you.

I’m happy to go on record, so to speak, as saying that most of these Fabs reissues aren’t meant for me. They’re meant, I suppose, for a medium-to-upper-level fan, but not an obsessive like me. I gotta know everything, including listening to the albums as they were intended. Like a trip to the past, preserved in amber.

So most of the content that these reissues have, I’ve had for years — I know people WAY more nuts than me, and they make sure I have everything. And the remixes to make the records sound more contemporary — a bit of EQ and compression — don’t add anything, except EQ and compression. They’re just different, and who needs the Mona Lisa presented as anything else? What — more vivid color?

I also love Sgt. Pepper as a stereo album, and always have, despite the “authenticity” of the mono LP. The Sgt. Pepper re-release, in its ne plus ultra release last year, at least added a few tracks I hadn’t heard; nothing revelatory, but decent. The album mix itself was still kind of meh though. I prefer (by a long way) the MoFi UHQR, or the off-the-stereo-master CD copy I’ve had since the mid-90s.

That’s a lot of words to say why I shouldn’t like this new record. So what’s coming next is obvious, right?

I think this new release is fantastic.

First of all, the basic tonal character of the album: The Beatles always sounded, I don’t know, a bit lifeless to me. At last by comparison to the previous two records. And I mean going all the way back to the original Capitol LP release and even including the MoFi box set. I’m tempted to call it dark, but not dark in the sense of EQ: dark as in lifeless, colorless.

Take “Martha My Dear”, maybe McCartney’s best track on the album, and one of my daughter’s favorite Fabs songs. There’s a complete absence of recording hiss, which usually I don’t like, but it stands out here. Maybe the technology has improved (after only 30+ years…). And the instruments and voices have a slightly greater presence — all of them. (The album is mastered very slightly hotter, but it’s not in Loudness War territory.)

Things are bit different on the album’s (slightly) arguably best track, “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”, too. For one thing, the vocals on the original sound, again, lifeless by comparison. The new release sounds as if they have some of the actual top end restored, and the level makes a bit more sense in the track. The bass has greater punch, and a bit more depth, and the hi-hat that introduces Ringo on the track is a little quieter than on the original and a bit more to the right. The whole track has more power — and amazingly enough I prefer it.

It’s tempting to pass judgment on the original mastering as being inadequate, but if that were the case, surely one of the many subsequent masterings would have corrected that. And the MoFi box set does, a very tiny bit.

Anyway, this will give an idea of the new mixes, but most people will want it (if they do) for the unreleased portion. I’ll pick out a few exceptional tracks from each of the four records.

The entire third disc is made up of the Esher demos, of course: the four Fabs hanging out at George’s swinging pad (his home studio) demoing the album (and then some). Of which I have personal favorites:

1) “Revolution”: an acoustic-guitar rave-up, with hand-percussion.

2) “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”

3) “Happiness is a Warm Gun” and “I’m So Tired”: the way these two tie together is pretty fascinating; a section from one ends up in another.

4) “Mother Nature’s Son”: the other great McCartney track. (Not appreciably different, just enough to make me want to hear it.)

The other three discs are from the album sessions, and offer a mixed bag. In particular, I question the inclusion of the version of “Hey Jude” that’s here (disc 5, track 3). There’s so much better a version to be had:

There’s a 10 and-a-half-minute version of “Revolution” that sets up “Revolution 9” perfectly. And the version of “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” on the first studio session disc is surprisingly groovy, for one of Paul’s “Granny tracks”. There’s a pretty heavy “Yer Blues” (disc 5, track 7) that will give the lie to those Stones partisans who think these guys couldn’t rock. Likewise with the fragment of “(You’re So Square) Baby I Don’t Care” that leads them into “Helter Skelter”. And a throbbing and slightly slower instrumental “Back In the USSR” (disc 5, track 10).

The overall sense from these four “in-process” discs is how much fun they were all having together. This is notoriously the album when they began to fracture, and Ringo DID quit the band for a couple weeks, but listening to it, not a trace of that is audible. This is the Fabs, still at the peak of their ability, and having a great time together.

Here’s a tracklist:

Disc 1:

01 – Back In The U.S.S.R. (2018 Mix)

02 – Dear Prudence (2018 Mix)

03 – Glass Onion (2018 Mix)

04 – Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da (2018 Mix)

05 – Wild Honey Pie (2018 Mix)

06 – The Continuing Story Of Bungalow Bill (2018 Mix)

07 – While My Guitar Gently Weeps (2018 Mix)

08 – Happiness Is A Warm Gun (2018 Mix)

09 – Martha My Dear (2018 Mix)

10 – I’m So Tired (2018 Mix)

11 – Blackbird (2018 Mix)

12 – Piggies (2018 Mix)

13 – Rocky Raccoon (2018 Mix)

14 – Don’t Pass Me By (2018 Mix)

15 – Why Don’t We Do It In The Road (2018 Mix)

16 – I Will (2018 Mix)

17 – Julia (2018 Mix)

Disc 2:

01 – Birthday (2018 Mix)

02 – Yer Blues (2018 Mix)

03 – Mother Nature’s Son (2018 Mix)

04 – Everybody’s Got Something To Hide Except Me And My Monkey (2018 Mix)

05 – Sexy Sadie (2018 Mix)

06 – Helter Skelter (2018 Mix)

07 – Long, Long, Long (2018 Mix)

08 – Revolution 1 (2018 Mix)

09 – Honey Pie (2018 Mix)

10 – Savoy Truffle (2018 Mix)

11 – Cry Baby Cry (2018 Mix)

12 – Revolution 9 (2018 Mix)

13 – Good Night (2018 Mix)

Disc 3:

01 – Back In The U.S.S.R. (Esher Demo)

02 – Dear Prudence (Esher Demo)

03 – Glass Onion (Esher Demo)

04 – Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da (Esher Demo)

05 – The Continuing Story Of Bungalow Bill (Esher Demo)

06 – While My Guitar Gently Weeps (Esher Demo)

07 – Happiness Is A Warm Gun (Esher Demo)

08 – I’m So Tired (Esher Demo)

09 – Blackbird (Esher Demo)

10 – Piggies (Esher Demo)

11 – Rocky Raccoon (Esher Demo)

12 – Julia (Esher Demo)

13 – Yer Blues (Esher Demo)

14 – Mother Nature’s Son (Esher Demo)

15 – Everybody’s Got Something To Hide Except Me And My Monkey (Esher Demo)

16 – Sexy Sadie (Esher Demo)

17 – Revolution (Esher Demo)

18 – Honey Pie (Esher Demo)

19 – Cry Baby Cry (Esher Demo)

20 – Sour Milk Sea (Esher Demo)

21 – Junk (Esher Demo)

22 – Child Of Nature (Esher Demo)

23 – Circles (Esher Demo)

24 – Mean Mr Mustard (Esher Demo)

25 – Polythene Pam (Esher Demo)

26 – Not Guilty (Esher Demo)

27 – What’s The New Mary Jane (Esher Demo)

Disc 4:

01 – Revolution 1 (Take 18)

02 – A Beginning (Take 4) Don’t Pass Me By (Take 7)

03 – Blackbird (Take 28)

04 – Everybody’s Got Something To Hide Except Me And My Monkey (Unumbered Rehearsal)

05 – Good Night (Unumbered Rehearsal)

06 – Good Night (Take 10 With A Guitar Part From Take 5)

07 – Good Night (Take 22)

08 – Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da (Take 3)

09 – Revolution (Unumbered Rehearsal)

10 – Revolution (Take 14 Instrumental Backing Track)

11 – Cry Baby Cry (Unumbered Rehearsal)

12 – Helter Skelter (First Version Take 2)

Disc 5:

01 – Sexy Sadie (Take 3)

02 – While My Guitar Gently Weeps (Acoustic Version Take 2)

03 – Hey Jude (Take 1)

04 – St Louis Blues (Studio Jam)

05 – Not Guilty (Take 102)

06 – Mother Nature’s Son (Take 15)

07 – Yer Blues (Take 5 With Guide Vocal)

08 – What’s The New Mary Jane (Take 1)

09 – Rocky Raccoon (Take 8)

10 – Back In The U.S.S.R. (Take 5 Instrumental Backing Track)

11 – Dear Prudence (Vocal, Guitar & Drums)

12 – Let It Be (Unumbered Rehearsal)

13 – While My Guitar Gently Weeps (Third Version Take 27)

14 – (You’re So Square) Baby I Don’t Care (Studio Jam)

15 – Helter Skelter (Second Version Take 17)

16 – Glass Onion (Take 10)

Disc 6:

01 – I Will (Take 13)

02 – Blue Moon (Studio Jam)

03 – I Will (Take 29)

04 – Step Inside Love (Studio Jam)

05 – Los Paranoias (Studio Jam)

06 – Can You Take Me Back (Take 1)

07 – Birthday (Take 2 Instrumental Backing Track)

08 – Piggies (Take 12 Instrumental Backing Track)

09 – Happiness Is A Warm Gun (Take 19)

10 – Honey Pie (Instrumental Backing Track)

11 – Savoy Truffle (Instrumental Backing Track)

12 – Martha My Dear (Without Brass And Strings)

13 – Long, Long, Long (Take 44)

14 – I’m So Tired (Take 7)

15 – I’m So Tired (Take 14)

16 – The Continuing Story Of Bungalow Bill (Take 2)

17 – Why Don’t We Do It In The Road (Take 5)

18 – Julia (Two Rehearsals)

19 – The Inner Light (Take 6 Instrumental Backing Track)

20 – Lady Madonna (Take 2 Piano & Drums)

21 – Lady Madonna (Backing Vocals From Take 3)

22 – Across The Universe (Take 6)

Telling the Story

Every picture tells a story.

That’s utterly true, regardless of Rod Stewart. And if every picture can speak, so can all the music ever made. It’s always useful to remind ourselves of just how that works.

Let’s begin with Bach, specifically the Prelude from Cello Suite No. 4 in E-flat:

To recap: (1) Up to 26”, we’re setting the scene. It consists of a series of arpeggiated chords, each launched by a bass note and a leap upward, then statements of the chord that drift downward before another bass note launches another leap, and so forth. The scope of this chord sequence is limited; even though each chord-phrase is immediately repeated, our sequence returns safely home to the tonic chord in under half a minute. (2) At 27” the harmonies begin to wander further afield: our heroine’s adventure into a wider world has begun. Now chords are less likely to be repeated, as the material plunges into territory that feels darker, more complex, more significant somehow, even while the basic chord-phrase remains consistent. You can think of that basic phrase as our heroine, whereas the rapidly changing chords represent the path she’s taking through the forest, a path that becomes ever more twisty, the trees looming overhead ever more ominously. (3) At 2’27”, anxiety overcomes our adventurer. She slows, then stops. The next sound we hear is not her arpeggio figure, but a skittering, anxious series of scales. She attempts to return to the chord-phrases, but that’s not easy. Panic has seized her; the crisis will not abate without a struggle. But (to abandon the fairy tale for a moment) this is a short instrumental piece, not a grand opera or a Beethoven symphony. And so, (4) soon after the 3-minute mark, peace begins to return. Although the clouds never entirely lift—how could they?—our heroine safely reaches her grandmother’s house.

My point is, there’s always a story. If you’re going to have maximum fun with music, you should accept—nay, abandon yourself to—the notion of narrative. While you’re at it, you may as well learn all the different ways narrative can function. Three excerpts from Haydn symphonies offer pointed lessons. First, the Adagio of Symphony No. 26 in D Minor, “Lamentatione”:

One of Haydn’s early biographers asked the old composer whether he sought to “treat this or that literary subject of his own choosing” in his music. Haydn’s answer was emphatic:

Rarely. In instrumental music I generally gave entirely free rein to my purely musical imagination. Only one exception occurs to me now, when in the Adagio of a symphony I chose the theme of a conversation between God and a foolish sinner.

One musicologist has suggested that this Adagio was that of Symphony No. 26. You hear oboes and (eventually) horns play a Gregorian chant melody associated with Passiontide; meanwhile the first violins weave a garland of more ornate figures around the chant’s simple notes. As the movement goes on, that garland becomes increasingly active, gradually dominating the texture.

But it’s not convincing as a conversation, really. Where’s the back-and-forth? In fact Haydn was contributing to an established 18th-century tradition in which soloists added embellishments to a chant line. There’s no real exchange of remarks here; it’s the most static dialogue ever. He offers more compelling story-telling mimetics elsewhere. For instance, in a symphonic movement adapted from music for a play, Le distrait, we hear a portrait in swift strokes of two female characters, the ingénue Isabelle and the older Madame Grognac, who sternly countermands Isabelle’s graceful theme with pompous, martial motifs:

Talk about a Song Without Words; this suggests a whole scene!

The literary device of the unreliable narrator also pops up in Haydn symphonies, as well it might: early volumes of Sterne’s Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy began to appear in 1759. Although it’s unlikely Haydn ever read it, the novel has a playful way with narrative—Tristram can’t explain anything simply, so he spends more time in digressions than in actually telling his life story—which exemplifies the epoch’s obsession with intellectual games, satire as social critique, and more. Here is a similarly playful passage from Haydn’s Symphony No. 80 in D Minor, the likes of which were sharply criticized by certain contemporary critics because of their eccentric ( = unreliable) tone:

Following a grimly dramatic Sturm und Drang opening and modulation to the relative major, we get a secondary theme that minces along seemingly unaware of its triviality. Shocking! The development proceeds with similar alternations of the sublime and ridiculous. Having heard such juvenile nonsense, Hiller asked, how could anyone sustain belief in “the dignity of music”? How indeed?

We’ve been hearing clips from Giovanni Antonini’s remarkable series of Haydn symphonies and other 18th-century works for Alpha Classics. Two volumes, Nos. 5 “L’Homme de Génie” and 6 “Lamentatione,” appeared in 2017, none in 2018, but more are promised. I hope they arrive soon; these are hands-down the most engaging performances I’ve heard in years. They are surrounded by thematically related photos, essays, and contemporaneous music that provide a feast for listeners. Antonini honed his skills on Vivaldi, but his Haydn shows the same energy, wit, and attention to detail.

At this point our discussion should move to large-scale orchestral narratives, like those in symphonies by Shostakovich and his hero Mahler. Not going to happen! There’s scarcely space enough here to do justice to even a single such work, and long ago you will have already investigated (and re-investigated) your favorite “program” symphonies anyway. These works have staying power. Note that new recordings of Mahler’s Sixth and Shostakovich’s No. 11 “The Year 1905” were among the 25 Best Tracks cited in TMT #74. The latter work speaks—as symphonies are meant to speak—on behalf of an entire nation, remembering a historic cataclysm that, in 1956, resonated with fresh horror for many Russians. It’s one more reminder that a “classical” work can speak anew—even if ironically and unintentionally—to succeeding generations. (For Shostakovich, I’ll stick with Petrenko and the RLPO on Naxos, even though I’m happy the Boston SO is in Andris Nelsons’ hands these days.)

Let’s end with a small-scale work, David Lang’s mystery sonatas (Canteloupe). Like the Passacaglia in Biber’s “Mystery” Sonatas, these works are to be performed by a solo violinist without accompaniment. But whereas Biber’s mysteries are complex both technically and artistically, Lang’s are simple. That is a general characteristic of his music, and it can be vexing. Several years ago I happened to be at Zankel Hall when Paul Hillier and Theatre of Voices gave the U.S. premiere of The Little Match Girl Passion. In conversations afterwards with a couple of composers—out-of-towners like myself—I was struck by their vitriolic dismissal of Lang’s music, especially by comparison with Luciano Berio’s A-Ronne, also on the program and a work of stunning virtuosity. Wasn’t Lang cheating to write something as simplistic as Little Match Girl? How dare he?

Later in the season he won the Pulitzer Prize for it.

Back to mystery sonatas: in order to perceive this work as a story, you need to experience each movement in turn, accepting the narrative plan as a series of emotional states, not unlike the string of da capo arias that feature in a typical Handel opera. There, each aria features a single, unchanging Affekt that contributes to a sufficiently convincing flow of events and feelings. Lang’s seven movements are titled “Joy,” “After Joy,” “Before Sorrow,” “Sorrow,” and so forth. (Like I said, simple.)

Next time, we’ll tackle voiced narratives, especially requiems (by Berlioz, Harbison, Kastalsky) and opera (by two Finns, Saariaho and Fagerlund).