Part One of this report appeared in Issue 106. CanJam NYC 2020 took place on February 15 – 16 at New York’s Marriott Marquis and was well-attended by a diverse range of people young and old. The global CanJam shows are focused on headphones and associated gear – portable players, headphone amps, DACs, cables and accessories.

A whole lotta listenin' goin' on at the Focal exhibit.

The following are descriptions of some of the products that left the biggest impressions on me, along with a selection of product shots:

Tube Amp Retro Chic

While microprocessors and miniaturization of components has led to smaller DACs and headphone amplifiers, with some about the size of a pack of cigarettes, CanJam NYC 2020 had a surprisingly large number of exhibitors promoting dedicated tube amps for headphone listening.

Hearkening back to the 1950s and 1960s, vacuum tubes were largely replaced by transistors, semiconductors, and op-amps by the 1970s. Among the few industries still using vacuum tubes are high-voltage RF, select military technology equipment, guitar and other musical instrument amplifier manufacturers, some pro audio gear, and some high-end audio companies like McIntosh, Audio Research, VAC, VTL and a number of others. Eastern Europe and China are the only two regions remaining with any large-scale tube manufacturing factories, as Communist countries kept much of their tube-powered equipment in circulation long after tubes were mostly phased out in the West.

Absolutely stunning: the Manley Labs Absolute Headphone Amplifier.

I’ll admit that the presence of tube-powered headphone amps at CanJam NYC 2020 was a surprise to me, as this was my first CanJam. But given the more focused listening demanded by wearing headphones, the desire for the warmer sound of tube amplification to counter the brittle sterility of some digital music sources makes logical sense.

In addition to its headphones,

ZMF’s Pendant Amp ($1,999.99), sporting EL-84 and 12AX7 power and preamp tubes similar to a Vox guitar amp, was a somewhat appropriate, rather than anachronistic complement to the furniture-quality hardwood ZMF headphones on exhibit. The Pendant seemed to have a relatively transparent sound with a nice dose of tube warmth. The Pendant served as a high quality neutral sound source reference, with its volume knob being the only variable control on the unit.

Th ZMF Pendant headphone amplifier.

Well known for their audiophile tube amps, Serbia’s

Auris Audio showcased its latest product, the

Euterpe ($1,699). A multi-functional unit that can serve as a pure tube headphone amp, a DAC, or a preamp, the nearly 1-watt Euterpe comes housed in an attractive wooden base that can also double as a headphone stand. With USB, RCA, and 6.3mm stereo input and output jacks, the Euterpe can connect to computers, other DACs or other sound sources.

Striking design, inviting sound: the Euterpe from Auris Audio.

The warmth of the tube-powered Euterpe was evident from the get go. The only criticism I had was that the sound source was a notebook computer with a jazz Muzak playlist, so listening to other genres of music for the basis of comparison was not possible.

Auris also was promoting a new spinoff brand subsidiary:

EarMen. Located in Chicago, EarMen is a marketing arm for Auris’ portable DACs and headphone amps in a more affordable price range. The EarMen $249

Tr-Amp (a headphone amp/DAC) and humorously named

Donald DAC ($99) standalone DAC gathered a small crowd waiting to try them out.

Equinox had an attention-getting display.

Based in Maryland,

Corsonus is the brainchild of young entrepreneur Justin Chow. A former youth orchestra violinist, Chow became interested in headphones while in high school and got his start in electronics and DIY audio customization while in college. He only started learning the craft of machining in 2018!

Justin Chow of Corsonus.

The

Kodachi ($3,600) is a fully DC-coupled, tube/solid state hybrid amplifier. In the driver stage, it uses two 6SN7GTB tubes (and variants such as the Psvane CV181-Z). The power supplies including the tube heater supply are all fully-regulated, low-noise designs. The amp is available with a number of power tube, gain and other options.

The Corsonus Kodachi.

The chassis for both the amp and the seperate power supply are designed and milled by Chow out of a large block of billet aluminum. The power supply starts out at 15lb. and the amp is about 12lb. The separate chassis allow better thermal stability and heat dissipation.

The Kodachi is designed with special consideration to being able to drive electrostatic headphones. Comparing the different tube configurations available for the amp yielded very discernable differences in the same music references, which included excerpts from orchestral recordings, jazz from Snarky Puppy, and Led Zeppelin’s “Achilles Last Stand.” Transparency in the highs, midrange depth, and bass response and impact were all refined but altered for different tastes, not unlike using a Pultec Tube EQ-1 graphic equalizer to shape the sound in a recording studio.

Overall, a praiseworthy debut from a talented designer who clearly loves what he does.

The Dragon in the Room

One indication that a noticeable trend in an industry sector that has become too big to ignore is when it gets covered by conventional news outlets. In

The Wall Street Journal’s February 22, 2020 “Gear & Gadgets” section,

the entire article by Matthew Kronsberg was devoted to “Chi-Fi” - the constellation of Chinese-branded gearthat focuses on headphones, IEMs, DACs, headphone amps, and associated accessories. Although "Made in China" high quality levels are usually only associated with Western brand name electronics, CamJam featured many Chinese brands whose design, features, and performance easily rivalled those of their more expensive, better known competitors.

CanJam NYC 2020 had several rooms that were managed by Chinese dealer reps who were fluent in Chinese and English. They literally had so many tables festooned with the latest gear from so many different Chinese manufacturers that even the reps got momentarily confused as to which information went with which of their brands, due to their similarities of some of the products in appearance and use.

At least a dozen different smartphone-sized or smaller rechargeable DAC/headphone amps were on one table and they all looked like their chassis all came from the same factory, despite having different specs and subtly different sounds.

No stranger to the audiophile arena, Head-Fi.org sponsor

HIFIMAN was launched in New York 13 years ago by Dr. Fang Bian. HIFIMAN’s Reference line of audiophile products, including electrostatic and planar magnetic headphones, tube amps, and streaming audio devices, have been favorably reviewed in

Stereophile, Forbes, HiFi+, WIRED, and

TIME. The HIFIMAN product line also includes portable players, dynamic-driver closed- and open-back headphones, IEMs (in-ear monitors), digital-amplifier motherboard cards, and digital amps and DAC units in their Reference, Premium and Hi-Fi product lines. Prices range from $49 for the

RE300i, RE300a and RE300h earbuds to $6,000 for the

SUSVARA over-ear planar magnetic headphones. (The flagship

SHANGRI-LA electrostatic headphone system, which includes headphones and a tube amplifier, doesn’t have a published price.)

Cost-no-object headphone listening: the HIFIMAN Shangri-La.

Obtaining a private listening appointment, I was able to meet with Dr. Bian to listen to his

SHANGRI-LA Jr. electrostatic headphones and tube amp package unit ($8,000). With a range of classical and jazz SACD files from which to choose, the smoothness, detail and sense of presence from the SHANGRI-LA Jr. system was stunning. Every note was articulated and the three dimensionality of the space was natural and free of DSP artifacts.

Perhaps even more remarkable was HIFIMAN’s latest product, the

DEVA planar-magnetic over-ear Bluetooth headphones at $299. Designed as HIFIMAN’s entry-level audiophile headphones, its bang for the buck quality impressed me in the same way as the

AME Custom J1-U IEM (see

Part One of the CanJam NYC 2020 show report). Punching way above their weight class, the open-backed DEVA comes with a 6.5mm cable connection and a dedicated Bluetooth dongle for wireless use.

The DEVA easily rivaled comparable Bluetooth headphones from the more established European and American brands in sound quality, even those at higher prices. Listening to a mix of ambient rock from David Sylvian, solo jazz piano from Keith Jarrett and hard rock from the Foo Fighters, the DEVA complemented the music across all three genres with none of the sterility that some Bluetooth models sometimes exhibit due to signal compression or other factors. The dongle itself is a remarkable design. It supports hi-res LDAC and aptX HD and up to 24bit/192 kHz (via USB) and 24bit/96 kHz (from Bluetooth). Its built-in 2-channel DAC/filter and 1-watt per channel amp are probably a big part of its sonic excellence. Dr. Fang will have a likely winner on his hands with DEVA, given the popularity of Bluetooth and what I and others are seeing as a new trend back towards improved fidelity.

A DEVA that won't misbehave from HIFIMAN.

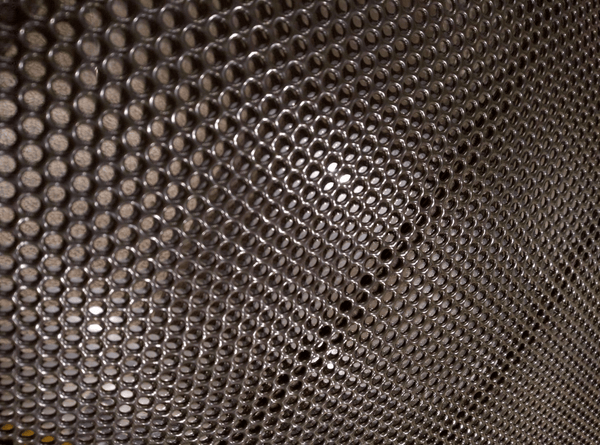

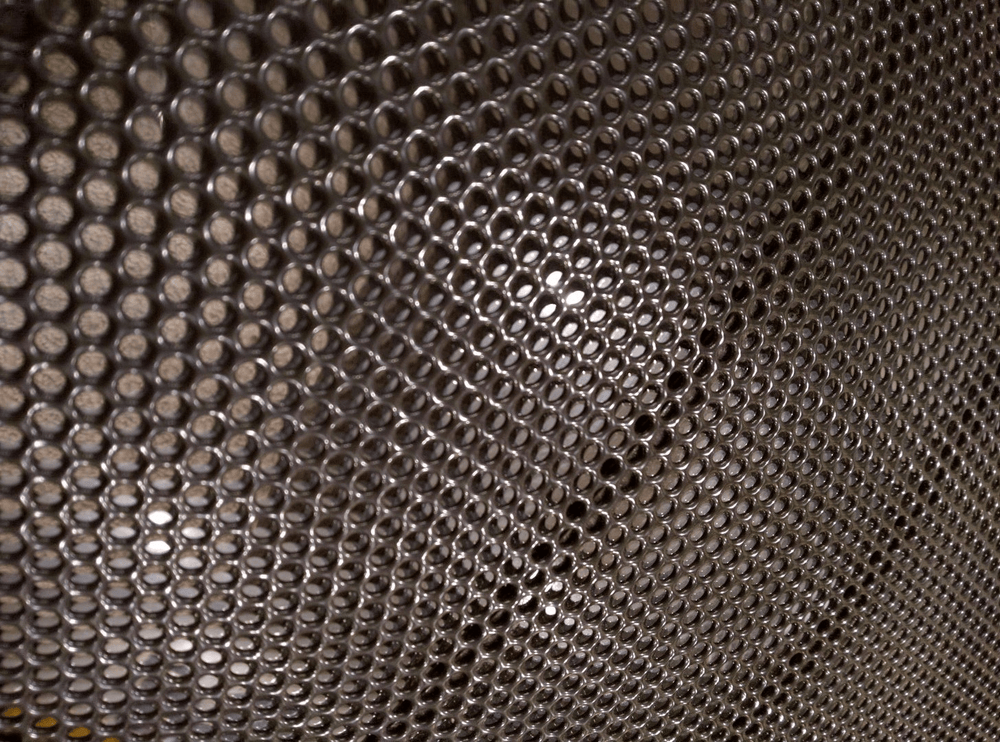

For high-end headphones in general one of the newer driver materials being touted for its sterling audio reproduction qualities is the rare earth metal beryllium. At roughly $50.00 per

gram, it is a difficult and costly metal to shape, due to scarcity and associated toxicity in processing. Nevertheless, beryllium is yielding the results that many headphone designers are seeking: significantly reduced distortion due to the metal’s stiffness to thickness ratio, while having the potential to deliver superior sound reproduction over conventional driver materials.

China’s global supremacy in the rare earth metals mining industry is unchallenged. Through its domestic deposits and exclusive international mining contracts in other countries, China controls close to 90% of the world’s rare earth metals deposits. This is a strategically enormous advantage for Chinese headphone manufacturers utilizing beryllium in their designs.

While ZMF’s $2,500

Vérité headphones use vapor-deposited beryllium drivers and AME uses beryllium coated drivers on some of their IMEs, Head-Fi.org sponsor

Dunu created a big buzz at CanJam with the release of their

LUNA ($1,699) IEM. The LUNA contains a

single sheet diaphragm made entirely of pure “acoustic grade” beryllium. Dunu’s past 17 years as an audiophile headphones manufacturer have established its reputation for excellent products. But it soon became clear to me that the LUNA was an engineering and design achievement comparable to the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing.

Earthly companion: DUNU's new LUNA.

Dunu’s Executive Director of Global Strategy and Management Tom Tsai spoke in detail about the R&D work that contributed to the making of the LUNA. In addition to the beryllium diaphragm, the earpiece shell is constructed of titanium alloy. Tsai explained that the inspiration for the aesthetic design of LUNA came from the Apollo 11 moon landing. The asymmetric lip shape, circular faceplate, concentric topographic map-like swirls and coloring were all related to the “moon” theme, with even the colors selected to match NASA photos of phases of the moon.

The LUNA sounded, not surprisingly, like an IEM version of the ZMF Vérité: lush, enhanced and richer sounds from familiar musical source content. If this is a common characteristic of beryllium (and not merely the result of design similarities between the two models), it is no wonder why the metal is so highly regarded for audiophile earphones design. The fact that Dunu can sell a pure beryllium driver-equipped LUNA IEM at $1,699 reflects, at least in part, the reduced access cost Chinese companies have to rare earth metals over their international rivals.

The aggressive dedication to R&D from Chinese companies like Dunu and HIFIMAN may likely result in new industry standards, much like the way Samsung’s Galaxy phones set the Android standard. These advances should continue to prosper, even in the wake of international emergency setbacks like Covid-19 that can halt trade.

CanJam NYC 2020 was an experience that certainly exceeded my expectations. It gave me a new and greater appreciation for how old and new tech can be combined for better listening experiences than what either old school tubes or cutting-edge digital might achieve individually.

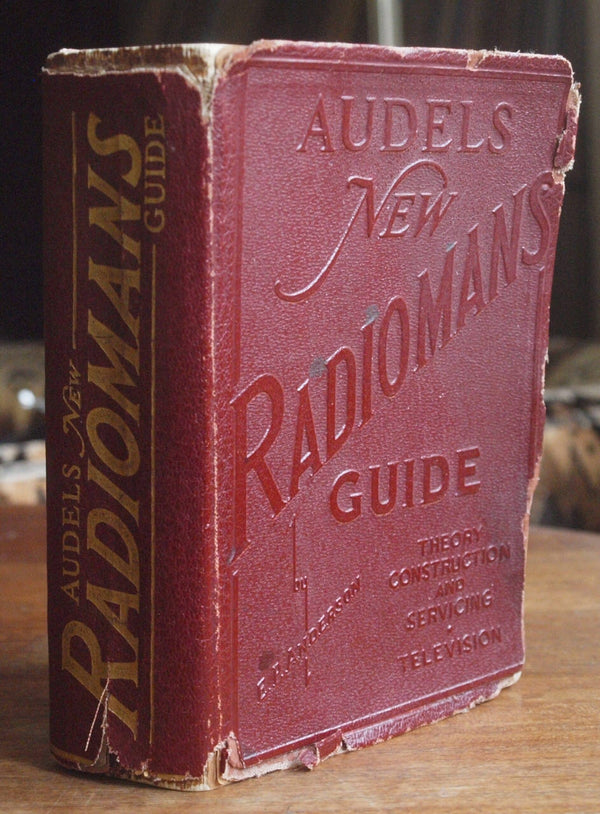

Balanced-armature construction (now found on many earbuds), said author E.P. Anderson, completely eliminated “chattering on loud signals, usually encountered in the magnetic type.” However, making it sensitive required such small air gaps between the voice coil and magnet that the coil might strike the magnet on loud bass notes, “emitting a rattling sound.” This is probably not a problem for earbuds, due to the much lower signal levels they handle.

Piezoelectric speakers used crystals that expanded and contracted with the signal’s fluctuations. They were “often used in connection with high-frequency reproduction.” “Metal strip” speakers (presumably what we’d call “ribbon” speakers now) and “induction” speakers were merely described.

The book explains why baffles are needed and how to calculate their size, but doesn’t discuss anything but flat-plane and backless baffles – no sealed or ported enclosures.

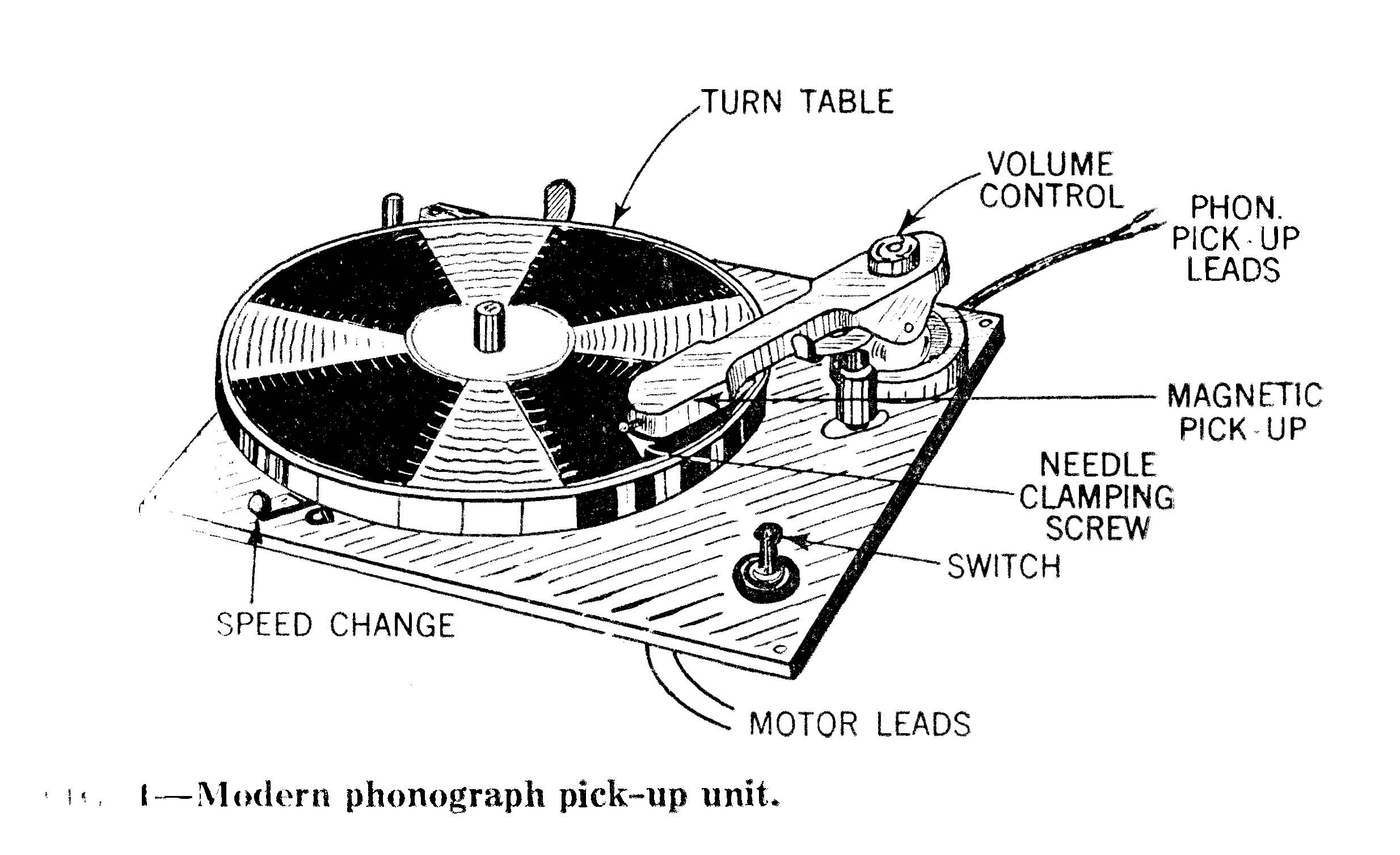

Phonographs: This being a “radioman’s” handbook, it considers a phonograph as a device converting needle vibrations into audio “for reproduction through a radio receiver.” The “modern phonograph pick-up unit” illustrated looks clunky by today’s standards, but not much more so than the Webcor changer my Dad bought in the early ‘50s.

Balanced-armature construction (now found on many earbuds), said author E.P. Anderson, completely eliminated “chattering on loud signals, usually encountered in the magnetic type.” However, making it sensitive required such small air gaps between the voice coil and magnet that the coil might strike the magnet on loud bass notes, “emitting a rattling sound.” This is probably not a problem for earbuds, due to the much lower signal levels they handle.

Piezoelectric speakers used crystals that expanded and contracted with the signal’s fluctuations. They were “often used in connection with high-frequency reproduction.” “Metal strip” speakers (presumably what we’d call “ribbon” speakers now) and “induction” speakers were merely described.

The book explains why baffles are needed and how to calculate their size, but doesn’t discuss anything but flat-plane and backless baffles – no sealed or ported enclosures.

Phonographs: This being a “radioman’s” handbook, it considers a phonograph as a device converting needle vibrations into audio “for reproduction through a radio receiver.” The “modern phonograph pick-up unit” illustrated looks clunky by today’s standards, but not much more so than the Webcor changer my Dad bought in the early ‘50s.

Of the four pickup cartridge types mentioned (condenser, carbon resistance, magnetic, and crystal), I’d expected piezoelectric crystal pickups to be emphasized. Crystal and, later, ceramic piezo cartridges predominated on simple phonographs for decades (our 1956 Webcor had one) because they were inexpensive and produced reasonably musical results without equalization. However, moving-coil magnetic pickups were covered in more depth; I guess moving-magnet types had to await stronger magnetic materials than were then available.

Styli were straight needles, held in by a set-screw for easy replacement. They must have needed replacement often: needles weren’t diamond-tipped, back then, and records were “made of hard materials, and . . . possess abrasive qualities sufficient to grind the needle point at the beginning of its travel in order to reduce the pressure of the needle.” More expensive radio-phonographs also had scratch filters.

Of the four pickup cartridge types mentioned (condenser, carbon resistance, magnetic, and crystal), I’d expected piezoelectric crystal pickups to be emphasized. Crystal and, later, ceramic piezo cartridges predominated on simple phonographs for decades (our 1956 Webcor had one) because they were inexpensive and produced reasonably musical results without equalization. However, moving-coil magnetic pickups were covered in more depth; I guess moving-magnet types had to await stronger magnetic materials than were then available.

Styli were straight needles, held in by a set-screw for easy replacement. They must have needed replacement often: needles weren’t diamond-tipped, back then, and records were “made of hard materials, and . . . possess abrasive qualities sufficient to grind the needle point at the beginning of its travel in order to reduce the pressure of the needle.” More expensive radio-phonographs also had scratch filters.

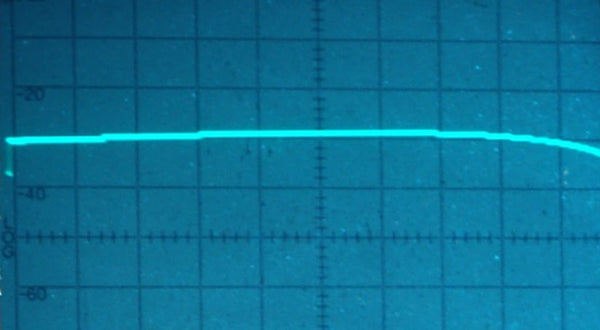

Fidelity? What’s that? Nowhere did I see any mention of distortion—even push-pull amplifiers are touted as producing higher power, not cleaner sound. The lone frequency-response graph, for “a typical radio receiver,” shows audio response down about 15 dB at 5 kHz for the upper reaches of the AM radio band, and -25 dB at a station frequency of 600 kHz. (Not that “kHz” wasn’t in use, yet—they said “kilocycles per second,” back then.)

Fidelity? What’s that? Nowhere did I see any mention of distortion—even push-pull amplifiers are touted as producing higher power, not cleaner sound. The lone frequency-response graph, for “a typical radio receiver,” shows audio response down about 15 dB at 5 kHz for the upper reaches of the AM radio band, and -25 dB at a station frequency of 600 kHz. (Not that “kHz” wasn’t in use, yet—they said “kilocycles per second,” back then.)

But though the Guide doesn’t mention it, progress toward higher fidelity had been going on for years. Stromberg-Carlson, for example, offered console radios with acoustical labyrinth speaker enclosures, essentially bass-reflex designs partitioned to form a long, folded tube that delayed the rear-wave from the speaker to prevent low-frequency cancellation. The U.S. Radio model 10-C was “equipped with 2 dynamic speakers (one tuned for bass—one for treble)”; both speakers were the same size, though, which would have restricted off-axis treble propagation. E.H. Scott Radio Laboratories (no relation to H.H. Scott) boasted “high-fidelity reproduction,” adding “you will hear tones you did not realize were there . . . . music . . . can now be heard with a faithfulness that will thrill every fibre of your being.” Companies such as E.H. Scott and Capehart were predecessors of today’s audio high-end, with exacting attention paid to audio, radio performance and (in Capehart’s case) exquisite cabinets.

But though the Guide doesn’t mention it, progress toward higher fidelity had been going on for years. Stromberg-Carlson, for example, offered console radios with acoustical labyrinth speaker enclosures, essentially bass-reflex designs partitioned to form a long, folded tube that delayed the rear-wave from the speaker to prevent low-frequency cancellation. The U.S. Radio model 10-C was “equipped with 2 dynamic speakers (one tuned for bass—one for treble)”; both speakers were the same size, though, which would have restricted off-axis treble propagation. E.H. Scott Radio Laboratories (no relation to H.H. Scott) boasted “high-fidelity reproduction,” adding “you will hear tones you did not realize were there . . . . music . . . can now be heard with a faithfulness that will thrill every fibre of your being.” Companies such as E.H. Scott and Capehart were predecessors of today’s audio high-end, with exacting attention paid to audio, radio performance and (in Capehart’s case) exquisite cabinets.

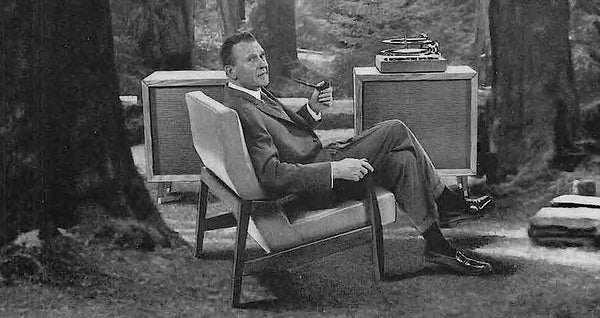

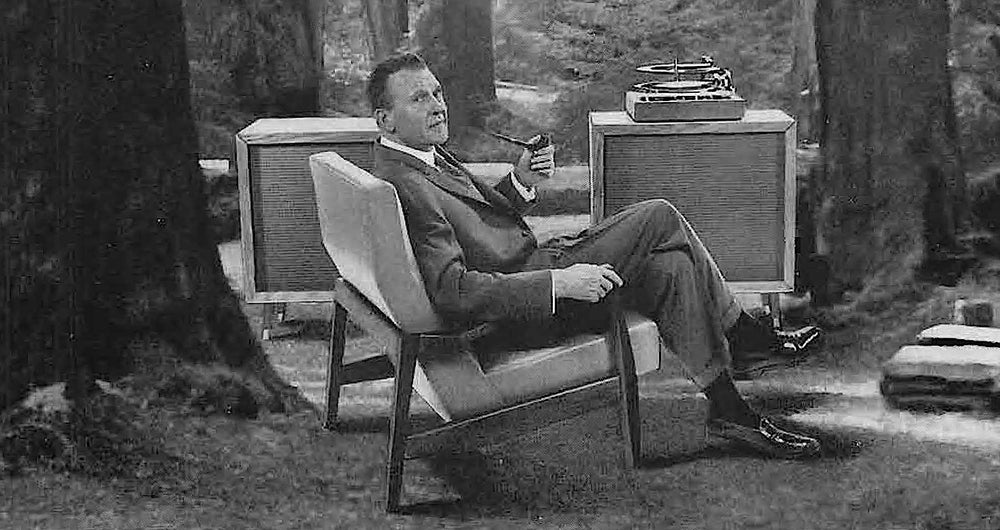

Interest in improved home audio didn’t become widespread until after World War II, when thousands of people educated in electronics by the military came home, and war-surplus electronics were on sale all over. Soon, there was a hi-fi industry, based on specialized components rather than console systems. By the 1950s, the term was so well-known that Max Factor brought out a “Hi-Fi Lipstick.”

Interest in improved home audio didn’t become widespread until after World War II, when thousands of people educated in electronics by the military came home, and war-surplus electronics were on sale all over. Soon, there was a hi-fi industry, based on specialized components rather than console systems. By the 1950s, the term was so well-known that Max Factor brought out a “Hi-Fi Lipstick.”

She wore her new Max Factor!

She wore her new Max Factor!

The classic Shure V15 Type V phono cartridge.

The classic Shure V15 Type V phono cartridge. MartinLogan CLS II electrostatic loudspeakers. Tricky to set up, but worth the effort.

MartinLogan CLS II electrostatic loudspeakers. Tricky to set up, but worth the effort. MartinLogan Spire loudspeakers. A hybrid design featuring an electrostatic panel mated with a dynamic woofer.

MartinLogan Spire loudspeakers. A hybrid design featuring an electrostatic panel mated with a dynamic woofer. The Oppo BDP-105 Universal/Blu-ray player. A modern classic, but sadly, the company is out of business.

The Oppo BDP-105 Universal/Blu-ray player. A modern classic, but sadly, the company is out of business. Nakamichi PA-7 power amplfier. Photo courtesy of

Nakamichi PA-7 power amplfier. Photo courtesy of  The Conrad-Johnson Premier Eleven amplifier.

The Conrad-Johnson Premier Eleven amplifier.

A whole lotta listenin' goin' on at the Focal exhibit.

A whole lotta listenin' goin' on at the Focal exhibit. Absolutely stunning: the Manley Labs Absolute Headphone Amplifier.

Absolutely stunning: the Manley Labs Absolute Headphone Amplifier. Th ZMF Pendant headphone amplifier.

Th ZMF Pendant headphone amplifier. Striking design, inviting sound: the Euterpe from Auris Audio.

Striking design, inviting sound: the Euterpe from Auris Audio. Equinox had an attention-getting display.

Equinox had an attention-getting display. Justin Chow of Corsonus.

Justin Chow of Corsonus. The Corsonus Kodachi.

The Corsonus Kodachi. Cost-no-object headphone listening: the HIFIMAN Shangri-La.

Cost-no-object headphone listening: the HIFIMAN Shangri-La. A DEVA that won't misbehave from HIFIMAN.

A DEVA that won't misbehave from HIFIMAN. Earthly companion: DUNU's new LUNA.

Earthly companion: DUNU's new LUNA.

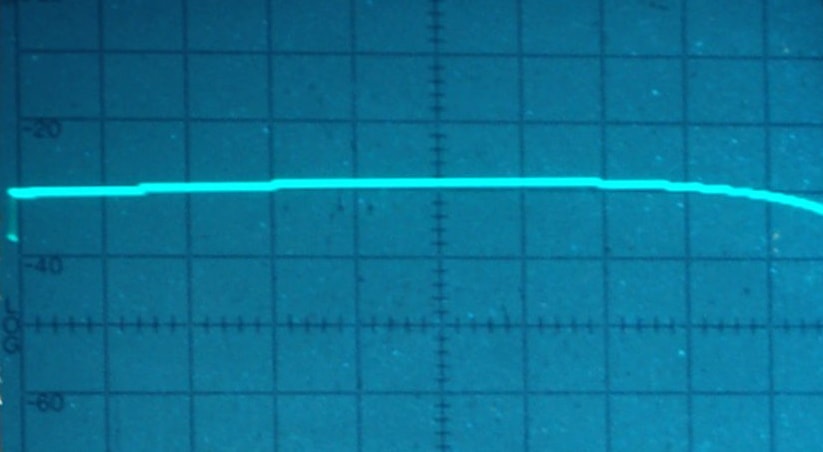

Average plate characteristics of an 845 triode from a 1933 RCA data sheet.

Average plate characteristics of an 845 triode from a 1933 RCA data sheet. The scope trace (on the right) shows a sine wave, close to the limit of the linear region of the circuit. The analyzer trace (on the left) shows the fundamental at 1 kHz (to the left of the screen) and a second harmonic component at 2 kHz, around 30 dB below the fundamental (3% second harmonic distortion, 10 dB/div on the vertical scale).

The scope trace (on the right) shows a sine wave, close to the limit of the linear region of the circuit. The analyzer trace (on the left) shows the fundamental at 1 kHz (to the left of the screen) and a second harmonic component at 2 kHz, around 30 dB below the fundamental (3% second harmonic distortion, 10 dB/div on the vertical scale).

As the amplitude of the 1 kHz sine wave is increased to exceed the linear region of operation of the amplifier, the scope trace shows a waveform with the negative peaks squashed, which is no longer symmetrical, due to the amplification not being linear. The analyzer trace displays the increase in the second harmonic distortion (the fundamental is displayed at the same level as before for an easy comparison), with the 2 kHz component now only about 14 dB below the fundamental (20% second harmonic distortion).

As the amplitude of the 1 kHz sine wave is increased to exceed the linear region of operation of the amplifier, the scope trace shows a waveform with the negative peaks squashed, which is no longer symmetrical, due to the amplification not being linear. The analyzer trace displays the increase in the second harmonic distortion (the fundamental is displayed at the same level as before for an easy comparison), with the 2 kHz component now only about 14 dB below the fundamental (20% second harmonic distortion).

For clarity, traces with no signal input (the 1 kHz sine wave oscillator being turned off) are also shown. The scope trace is a straight line along the middle of the screen, representing the “zero” voltage line. The signal consists of positive peaks (rising above zero) and negative peaks (below zero). On the analyzer, however, the zero line is at the bottom of the screen. The sign denoting a positive or negative peak is discarded and we only see the absolute value of amplitude at each frequency. With no fundamental present at 1 kHz, there is also no distortion component at 2 kHz. An ideal, perfectly linear amplifier, would only show the fundamental component as presented at its input, with no additional components. In practice, even laboratory grade oscillators will have some residual distortion components.

All real-life devices and circuits produce distortion to some extent.

For clarity, traces with no signal input (the 1 kHz sine wave oscillator being turned off) are also shown. The scope trace is a straight line along the middle of the screen, representing the “zero” voltage line. The signal consists of positive peaks (rising above zero) and negative peaks (below zero). On the analyzer, however, the zero line is at the bottom of the screen. The sign denoting a positive or negative peak is discarded and we only see the absolute value of amplitude at each frequency. With no fundamental present at 1 kHz, there is also no distortion component at 2 kHz. An ideal, perfectly linear amplifier, would only show the fundamental component as presented at its input, with no additional components. In practice, even laboratory grade oscillators will have some residual distortion components.

All real-life devices and circuits produce distortion to some extent.

3. That would seem to be a recurring non-motif in the music of Grimes, which is that there are many points of inflection but no commitment to any one style. People who live in boxes find this troubling; those who like to color outside the lines, who drew purple cows in grade school art class and didn’t see anything wrong with that, find Grimes appealing.

4. Grimes is not without roots in a fixed time and place. Listen to or especially watch her 2012 video for “Oblivion” at the start of her career, then listen to Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love.” You can get here from there.

5. She’s got everything she needs, she’s an artist, and she looks to the future, though surviving to live in any kind of future is a serious concern. The title “Miss Anthropocene” names her as a woman, perhaps The Woman, of her time: We are living in the Anthropocene age, “the period during which human activity has been the dominant influence on climate and the environment.” Underlying her approach to art is the sensible notion that unlike the environmentally aware musicians of a previous generation, who gave benefit concerts for whales, African famine, against nuclear power and for farmers, the species under direct attack is us. Our home planet has too many pressure faults, and we have to fix it now. That much of the world’s leadership is in denial about this was anticipated in the 1930s, when Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created the first Superman If you remember the plot basics, scientist Jor-El predicts doom for his imploding planet, while planet Krypton’s ruling class and science skeptic doom-deniers say nonsense. He builds a rocket to get his infant Kal-el to Earth just before Krypton explodes, as Jor-El predicted. The kid lands in Kansas and becomes Clark Kent.

6. Now watch the video to “So Heavy I Fell Through the Earth.” Asteroids and huge chunks of the third stone from the Sun are flying off into space. An avatar of a woman with a sword or similar is engaged in a battle with a raptor. There’s a definite erotic charge as the woman with the sword gets close to the raptor’s mouth, parry and thrust, in and out, approach and withdraw. By the end of the six minute mini-movie you’ll wonder of there is some sort of copulation/capitulation. Are she and the raptor enemies or dueling and flirting, for sport, engaged in a friendly sex game as we await the same fate of flying dinosaurs: extinction.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iH0kfH04U68

7. In an interview, Grimes tells The Face that she has created an avatar called WarNymph. The avatar has allowed her to keep working through her pregnancy. Vogue magazine shows her pregnant, complete with self-written diagrams written on her bulging belly. The father is Tesla man and successful civilian rocketeer Elon Musk. Las Vegas bookmakers say that the chance of their child being named James or Jane, or John or Susan, are a bazillion kazillion Krypton dollars to one. Grimes worries that her online fan base has already mentioned a few of the unusual names that mom and dad had considered.

8. Go back and listen to some tracks from Grimes’ last album, Art Angels from 2015. The cover features two animated characters: a cute anime character and a larger three-eyed creature, conventionally “alien,” with tears of blood coming through the eyes. Whoever she is, she has her eyes on the prize. It’s a really impressive album of sophisticated synth pop, though strangely, Grimes now regrets it. In April 2019, she told Stereogum, which had named it its No. 1 album of 2015, “a piece of crap...a stain.” What she meant was, it was a pop record, which I think means she was experimenting with pop, and it came off more pop than experiment: “a genre exercise,” as she puts it. Note that “genre exercise” is a phrase used almost exclusively by rock and pop critics, when a band explores a singular style, or reverts to an earlier one: the Rolling Stones blues album Blue and Lonesome could be “a genre exercise”; the Byrds’ country album Sweetheart of the Rodeo was not a genre exercise, since it solidified a new genre: country-rock. I nevertheless see Art Angels as a “seminal album” (Quotes or air quotes mine to indicate that this too is a pop critic cliché best avoided). What I want to say is that it is a transitional album, still anchored in dance pop but displaying her powerful multi-octave range, contrasts not often heard in clubs: check out “California” with heavy bass and drums and ethereality, and a sort of rebellious vision, as if Mariah Carey had Laurie Anderson’s irony and IQ. But maybe calling a song “California” is too obvious for Grimes. And “Kill v. Maim” has a relentless intensity that may be, in retrospect, a genre-exercise in 1990s Madonna. The video, as always, is great, created by Grimes and her talented brother Mac Boucher. It takes place in the ruins of an abandoned or just filthy subway station, with plenty of women menacing women wearing fishnet everywhere. (Grimes is wearing a VERSACE sweatshirt). Our current pandemic fears are anticipated by many wearing protective medical masks, and at the end of this otherwise typical zombie apocalypse are the words: YOU DIED.

9. Back to the new album. Among other necessary songs are “My Name is Dark,” an electro-rocking “Sympathy for the Devil” featuring computer swooshes rather than electric guitars, and “4 AEM,” an elegant hymn to loneliness and desire.

10. To the degree that the “Delete Forever” video reminds you of Katy Perry, be aware that Grimes is conscious of the thin line between imitation and the sui generis for which she strives. She is in on the joke.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gvzC8MmC850

11. There are two video versions of “Idoru,” the “slightly longer version” (almost seven minutes) and the “slightly shorter version” at 5 minutes 19 seconds. The videos have an Asian motif long loved by Grimes (see “Realiti” from 2015). “Idoru” is a Japanese word that resembles “idol,” but it refers to a specifically Japanese kind of teen idol. According to the Rice University neologisms database, an Idoru is a “young pampered female Japanese pop icon,” especially a manufactured one. In other words, an idoru is sort of like a solo woman artist version of the boy bands so popular in Japan and Korea, although young girl and mixed groups are becoming increasingly popular in K-pop. It is also noteworthy that Idoru is also the name of the second book of novelist William Gibson’s cyberpunk trilogy “Bridge Trilogy.”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oCrhTU9HkVQ

12. All resemblances to Gibson’s book are intentional. In the video (maybe just the shorter version) Grimes is seen holding a copy, that is dedicated to her (“Claire”). One of the characters in Gibson’s book is a virtual reality superstar idolized in Japan named Rei Toei. Oh, and both Gibson and Grimes live in Vancouver.

13. In the “Idoru” video flower petals (cherry blossoms? Or giant pollen clusters) drift down. Grimes is wearing a vintage wedding dress, wielding a sword with a white flag attached. Her plentiful make up is applied asymmetrically: big ball of rouge on one cheek, smaller, off-color rouge on the other. Her fingernails are like talons. The pigtails she wears are rooted so high on her head that she is essentially bald at the top of her head. During the video, according to the online webzine Fact, there are also scenes from a 1990s anime

3. That would seem to be a recurring non-motif in the music of Grimes, which is that there are many points of inflection but no commitment to any one style. People who live in boxes find this troubling; those who like to color outside the lines, who drew purple cows in grade school art class and didn’t see anything wrong with that, find Grimes appealing.

4. Grimes is not without roots in a fixed time and place. Listen to or especially watch her 2012 video for “Oblivion” at the start of her career, then listen to Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love.” You can get here from there.

5. She’s got everything she needs, she’s an artist, and she looks to the future, though surviving to live in any kind of future is a serious concern. The title “Miss Anthropocene” names her as a woman, perhaps The Woman, of her time: We are living in the Anthropocene age, “the period during which human activity has been the dominant influence on climate and the environment.” Underlying her approach to art is the sensible notion that unlike the environmentally aware musicians of a previous generation, who gave benefit concerts for whales, African famine, against nuclear power and for farmers, the species under direct attack is us. Our home planet has too many pressure faults, and we have to fix it now. That much of the world’s leadership is in denial about this was anticipated in the 1930s, when Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created the first Superman If you remember the plot basics, scientist Jor-El predicts doom for his imploding planet, while planet Krypton’s ruling class and science skeptic doom-deniers say nonsense. He builds a rocket to get his infant Kal-el to Earth just before Krypton explodes, as Jor-El predicted. The kid lands in Kansas and becomes Clark Kent.

6. Now watch the video to “So Heavy I Fell Through the Earth.” Asteroids and huge chunks of the third stone from the Sun are flying off into space. An avatar of a woman with a sword or similar is engaged in a battle with a raptor. There’s a definite erotic charge as the woman with the sword gets close to the raptor’s mouth, parry and thrust, in and out, approach and withdraw. By the end of the six minute mini-movie you’ll wonder of there is some sort of copulation/capitulation. Are she and the raptor enemies or dueling and flirting, for sport, engaged in a friendly sex game as we await the same fate of flying dinosaurs: extinction.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iH0kfH04U68

7. In an interview, Grimes tells The Face that she has created an avatar called WarNymph. The avatar has allowed her to keep working through her pregnancy. Vogue magazine shows her pregnant, complete with self-written diagrams written on her bulging belly. The father is Tesla man and successful civilian rocketeer Elon Musk. Las Vegas bookmakers say that the chance of their child being named James or Jane, or John or Susan, are a bazillion kazillion Krypton dollars to one. Grimes worries that her online fan base has already mentioned a few of the unusual names that mom and dad had considered.

8. Go back and listen to some tracks from Grimes’ last album, Art Angels from 2015. The cover features two animated characters: a cute anime character and a larger three-eyed creature, conventionally “alien,” with tears of blood coming through the eyes. Whoever she is, she has her eyes on the prize. It’s a really impressive album of sophisticated synth pop, though strangely, Grimes now regrets it. In April 2019, she told Stereogum, which had named it its No. 1 album of 2015, “a piece of crap...a stain.” What she meant was, it was a pop record, which I think means she was experimenting with pop, and it came off more pop than experiment: “a genre exercise,” as she puts it. Note that “genre exercise” is a phrase used almost exclusively by rock and pop critics, when a band explores a singular style, or reverts to an earlier one: the Rolling Stones blues album Blue and Lonesome could be “a genre exercise”; the Byrds’ country album Sweetheart of the Rodeo was not a genre exercise, since it solidified a new genre: country-rock. I nevertheless see Art Angels as a “seminal album” (Quotes or air quotes mine to indicate that this too is a pop critic cliché best avoided). What I want to say is that it is a transitional album, still anchored in dance pop but displaying her powerful multi-octave range, contrasts not often heard in clubs: check out “California” with heavy bass and drums and ethereality, and a sort of rebellious vision, as if Mariah Carey had Laurie Anderson’s irony and IQ. But maybe calling a song “California” is too obvious for Grimes. And “Kill v. Maim” has a relentless intensity that may be, in retrospect, a genre-exercise in 1990s Madonna. The video, as always, is great, created by Grimes and her talented brother Mac Boucher. It takes place in the ruins of an abandoned or just filthy subway station, with plenty of women menacing women wearing fishnet everywhere. (Grimes is wearing a VERSACE sweatshirt). Our current pandemic fears are anticipated by many wearing protective medical masks, and at the end of this otherwise typical zombie apocalypse are the words: YOU DIED.

9. Back to the new album. Among other necessary songs are “My Name is Dark,” an electro-rocking “Sympathy for the Devil” featuring computer swooshes rather than electric guitars, and “4 AEM,” an elegant hymn to loneliness and desire.

10. To the degree that the “Delete Forever” video reminds you of Katy Perry, be aware that Grimes is conscious of the thin line between imitation and the sui generis for which she strives. She is in on the joke.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gvzC8MmC850

11. There are two video versions of “Idoru,” the “slightly longer version” (almost seven minutes) and the “slightly shorter version” at 5 minutes 19 seconds. The videos have an Asian motif long loved by Grimes (see “Realiti” from 2015). “Idoru” is a Japanese word that resembles “idol,” but it refers to a specifically Japanese kind of teen idol. According to the Rice University neologisms database, an Idoru is a “young pampered female Japanese pop icon,” especially a manufactured one. In other words, an idoru is sort of like a solo woman artist version of the boy bands so popular in Japan and Korea, although young girl and mixed groups are becoming increasingly popular in K-pop. It is also noteworthy that Idoru is also the name of the second book of novelist William Gibson’s cyberpunk trilogy “Bridge Trilogy.”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oCrhTU9HkVQ

12. All resemblances to Gibson’s book are intentional. In the video (maybe just the shorter version) Grimes is seen holding a copy, that is dedicated to her (“Claire”). One of the characters in Gibson’s book is a virtual reality superstar idolized in Japan named Rei Toei. Oh, and both Gibson and Grimes live in Vancouver.

13. In the “Idoru” video flower petals (cherry blossoms? Or giant pollen clusters) drift down. Grimes is wearing a vintage wedding dress, wielding a sword with a white flag attached. Her plentiful make up is applied asymmetrically: big ball of rouge on one cheek, smaller, off-color rouge on the other. Her fingernails are like talons. The pigtails she wears are rooted so high on her head that she is essentially bald at the top of her head. During the video, according to the online webzine Fact, there are also scenes from a 1990s anime

It didn’t work that way.

It allowed the “hub” talent to pre-record their shows, which could then be inserted into the “spoke” stations via computer. Record and insert. This could, and did, happen across markets. Soon, locals were fired and replaced by someone on the wide area network. The replacements would be paid a fraction of the former full timer’s salary. (Example, A $30,000 a year plus benefits employee expense would be reduced to $5,000 with no benefits.) Local talent was lost for all but the very best remote-location DJs who actually prepared and studied for the markets they would do voice tracks for.

Air personalities were told that if they talked more than eight seconds, they’d lose audience. Yet the stations would play as many as eight minutes of commercials in a row, usually 30-second ads. When the music stopped twice an hour, there could be 12, 14, or 16 commercials in a row. Hypocrisy. Then some stations would play long sweeps of music at prime times, only to have to make up for the lost spots in the following hours, so there would be even more commercials then.

People always ask why radio plays the same songs over and over, when there are so many other songs they could play. The answer is simply that when people tune in, they want to hear their favorites. We spent a lot of money to find out what those songs were, then tried to mix them so they’d repeat in a way to “stretch plays out” – for example, if played in the morning, the songs would be then played in the evening, then the afternoon, before returning to being played yet again in the morning.

Every station that tried to add songs beyond the favorites lost ratings.

You might think people want variety, but if that leads to unfamiliar music, or polarized songs, it doesn’t.

Think of radio station playlists this way. You go to a concert for a group you like. Steely Dan? Don’t you want to hear “Hey Nineteen?” “Gaslighting Abbie,” maybe not so much.

When life intrudes, people’s interest in music is displaced. The music they grew up with becomes a marker back to those good old days. New music doesn’t have that magnetism, even if it’s good. Radio is about instant gratification, or the listener will move on. So you can’t count on listeners paying attention deeply enough to get into a song they don’t know.

Programmers know how long a station’s core audience listens – and at what times. Those heavy listeners comprise 80 percent of the station’s audience at any minute. You can then calculate how many times to play a current song (or power library cut) to hit the largest percentage of your daily/weekly audience.

We had research groups of likely listeners who would rate each song. Some songs would turn out to be “universals,” liked by everyone. Some would be peculiar to a certain age group or sex within the target audience. We could also get the song-by-song playlists of virtually any other station to see if they had discovered some songs we hadn’t tested.

Hit songs are like endorphins.

Oldies, for seniors or older folks mostly, are like a serious dose of endorphins for them.

Christmas music: big squirt of endorphins. When stations go all-Christmas they can triple their audience. Think of what that music takes you back to...presents, family, happy happy.

Since the early 2000s, corporate control has increased. Local program directors now have little power compared to my days when my on-air freedom was virtually unlimited. Corporate “initiatives” rule the formats now. Vice presidents of formats (and yes, there are VPs for each format) force obedience. Freed from previous government regulations, the large companies bought so many stations on shaky financial terms that debt became a major factor. Bankruptcies ensued. Then competition for advertising from digital media like streaming and internet radio sucked even more blood from radio.

These days I find it hard to listen to radio because as a former program director, I know what’s wrong, and a lot is wrong. I can’t listen as an audiophile because most stations hammer their audio with multiband automatic gain controls, limiters, compressors and clippers. Theory says listeners prefer the louder sound. Perhaps not the loudest distortion. And as popular music is compressed to death to start with, the audio largely sucks.

Today, corporate radio is pretty much a morning show followed by a jukebox. iHeartMedia recently completed another round of layoffs and is building a number of “AI-enabled Centers of Excellence.”

I went into a station multi-station cluster on a weekend some years back. There were six stations broadcasting. And not a soul in the building.

Since 1976 I have been doing voiceover work – acting or announcing in commercials, being the “voice” of TV stations, radio stations, and a variety of other types of work. In subsequent articles I will touch on that.

It didn’t work that way.

It allowed the “hub” talent to pre-record their shows, which could then be inserted into the “spoke” stations via computer. Record and insert. This could, and did, happen across markets. Soon, locals were fired and replaced by someone on the wide area network. The replacements would be paid a fraction of the former full timer’s salary. (Example, A $30,000 a year plus benefits employee expense would be reduced to $5,000 with no benefits.) Local talent was lost for all but the very best remote-location DJs who actually prepared and studied for the markets they would do voice tracks for.

Air personalities were told that if they talked more than eight seconds, they’d lose audience. Yet the stations would play as many as eight minutes of commercials in a row, usually 30-second ads. When the music stopped twice an hour, there could be 12, 14, or 16 commercials in a row. Hypocrisy. Then some stations would play long sweeps of music at prime times, only to have to make up for the lost spots in the following hours, so there would be even more commercials then.

People always ask why radio plays the same songs over and over, when there are so many other songs they could play. The answer is simply that when people tune in, they want to hear their favorites. We spent a lot of money to find out what those songs were, then tried to mix them so they’d repeat in a way to “stretch plays out” – for example, if played in the morning, the songs would be then played in the evening, then the afternoon, before returning to being played yet again in the morning.

Every station that tried to add songs beyond the favorites lost ratings.

You might think people want variety, but if that leads to unfamiliar music, or polarized songs, it doesn’t.

Think of radio station playlists this way. You go to a concert for a group you like. Steely Dan? Don’t you want to hear “Hey Nineteen?” “Gaslighting Abbie,” maybe not so much.

When life intrudes, people’s interest in music is displaced. The music they grew up with becomes a marker back to those good old days. New music doesn’t have that magnetism, even if it’s good. Radio is about instant gratification, or the listener will move on. So you can’t count on listeners paying attention deeply enough to get into a song they don’t know.

Programmers know how long a station’s core audience listens – and at what times. Those heavy listeners comprise 80 percent of the station’s audience at any minute. You can then calculate how many times to play a current song (or power library cut) to hit the largest percentage of your daily/weekly audience.

We had research groups of likely listeners who would rate each song. Some songs would turn out to be “universals,” liked by everyone. Some would be peculiar to a certain age group or sex within the target audience. We could also get the song-by-song playlists of virtually any other station to see if they had discovered some songs we hadn’t tested.

Hit songs are like endorphins.

Oldies, for seniors or older folks mostly, are like a serious dose of endorphins for them.

Christmas music: big squirt of endorphins. When stations go all-Christmas they can triple their audience. Think of what that music takes you back to...presents, family, happy happy.

Since the early 2000s, corporate control has increased. Local program directors now have little power compared to my days when my on-air freedom was virtually unlimited. Corporate “initiatives” rule the formats now. Vice presidents of formats (and yes, there are VPs for each format) force obedience. Freed from previous government regulations, the large companies bought so many stations on shaky financial terms that debt became a major factor. Bankruptcies ensued. Then competition for advertising from digital media like streaming and internet radio sucked even more blood from radio.

These days I find it hard to listen to radio because as a former program director, I know what’s wrong, and a lot is wrong. I can’t listen as an audiophile because most stations hammer their audio with multiband automatic gain controls, limiters, compressors and clippers. Theory says listeners prefer the louder sound. Perhaps not the loudest distortion. And as popular music is compressed to death to start with, the audio largely sucks.

Today, corporate radio is pretty much a morning show followed by a jukebox. iHeartMedia recently completed another round of layoffs and is building a number of “AI-enabled Centers of Excellence.”

I went into a station multi-station cluster on a weekend some years back. There were six stations broadcasting. And not a soul in the building.

Since 1976 I have been doing voiceover work – acting or announcing in commercials, being the “voice” of TV stations, radio stations, and a variety of other types of work. In subsequent articles I will touch on that.

Arthur Brown – “We’ve Gotta Get Out of This Place” (The Animals)

You probably only know him as “The God of Hellfire” from his 1968 hit, “Fire.” Possessed of a multi-octave vocal range, he has continued to record and perform (at age 77) to this day. I’ve been a fan from the beginning, and will do a feature on him in Copper at some point. In the mid- 1970s, after three wild, spacy, progressive albums with his band, Kingdom Come (not the metal band of the late ‘80s), he took a detour back toward pop. The album, Dance, was much more subdued, but featured this bouncy version of the Animals’ hit.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=atEzLhIn9Zg

Arthur Brown – “We’ve Gotta Get Out of This Place” (The Animals)

You probably only know him as “The God of Hellfire” from his 1968 hit, “Fire.” Possessed of a multi-octave vocal range, he has continued to record and perform (at age 77) to this day. I’ve been a fan from the beginning, and will do a feature on him in Copper at some point. In the mid- 1970s, after three wild, spacy, progressive albums with his band, Kingdom Come (not the metal band of the late ‘80s), he took a detour back toward pop. The album, Dance, was much more subdued, but featured this bouncy version of the Animals’ hit.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=atEzLhIn9Zg

Shaun Cassidy – “It’s My Life” (The Animals)

Yes, I said Shaun Cassidy – 1970s teen idol, brother of David Cassidy (another teen idol). Apparently, Shaun wanted to jettison that image, and in 1980 enlisted the help of rock legend Todd Rundgren. With production by Rundgren and musical accompaniment by members of Rundgren’s band Utopia, Cassidy played chameleon, shedding his previous sound like so much dried skin as he ran through cover songs that included David Bowie’s “Rebel Rebel” and Ian Hunter’s “Once Bitten, Twice Shy.” This is a track to put on and stump your friends – I’ll bet at least one will guess Iggy Pop…

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cF-dEA-BXTo

Burton Cummings – “You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet” (Bachman-Turner Overdrive)

Following the massive success of The Guess Who’s American Woman (both album and single) in 1970, guitarist and founding member Randy Bachman fell ill and converted to Mormonism. This led to a rift with co-founder Burton Cummings, and Bachman left the group after a 1970 gig at the Fillmore East. He went on to have a number of hits with Bachman-Turner Overdrive, including “You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet.”

Evidence of the bad blood between Bachman and Cummings was on full display years later in this quote from a 1974 Rolling Stone interview with Cummings: “When I see Bachman and Fred Turner, both 250-odd pound guys, slinking and sashaying around onstage . . .it just doesn’t work for me. It’s like seeing the f*ckin’ hippos on ice skates doing Nutcracker Suite in little frilly skirts.”

The animosity was still festering when Cummings released his self-titled solo album in 1976. Pay particular attention to the solo in the middle.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M1bijvblzEE

DREAD ZEPPELIN – “Your Time is Gonna Come” (Led Zeppelin)

Is it cheating to include this? I don’t think so. Imagine some guys sitting around, and one of them says, “Let’s form a Led Zeppelin cover band, but let’s do the songs reggae-style, and get an Elvis impersonator for our lead vocalist!” Good drugs, right? Well, Dread Zeppelin pulls it off with superb musicianship and a great sense of humor.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aNBFy4C8Vuc

BRYAN FERRY – “It’s My Party” (Leslie Gore)

Roxy Music’s lead singer put out his first solo album of cover songs in 1973, when his vocal style was still, shall we say, “mannered.” Nearly ten years later, Ferry’s smooth, melodic crooning on Avalon, Boys and Girls, and Bête Noire would earn him a large following. Note that he doesn’t bother to change the lyrics here to fit his gender.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X6fqDVe863o

Shaun Cassidy – “It’s My Life” (The Animals)

Yes, I said Shaun Cassidy – 1970s teen idol, brother of David Cassidy (another teen idol). Apparently, Shaun wanted to jettison that image, and in 1980 enlisted the help of rock legend Todd Rundgren. With production by Rundgren and musical accompaniment by members of Rundgren’s band Utopia, Cassidy played chameleon, shedding his previous sound like so much dried skin as he ran through cover songs that included David Bowie’s “Rebel Rebel” and Ian Hunter’s “Once Bitten, Twice Shy.” This is a track to put on and stump your friends – I’ll bet at least one will guess Iggy Pop…

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cF-dEA-BXTo

Burton Cummings – “You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet” (Bachman-Turner Overdrive)

Following the massive success of The Guess Who’s American Woman (both album and single) in 1970, guitarist and founding member Randy Bachman fell ill and converted to Mormonism. This led to a rift with co-founder Burton Cummings, and Bachman left the group after a 1970 gig at the Fillmore East. He went on to have a number of hits with Bachman-Turner Overdrive, including “You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet.”

Evidence of the bad blood between Bachman and Cummings was on full display years later in this quote from a 1974 Rolling Stone interview with Cummings: “When I see Bachman and Fred Turner, both 250-odd pound guys, slinking and sashaying around onstage . . .it just doesn’t work for me. It’s like seeing the f*ckin’ hippos on ice skates doing Nutcracker Suite in little frilly skirts.”

The animosity was still festering when Cummings released his self-titled solo album in 1976. Pay particular attention to the solo in the middle.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M1bijvblzEE

DREAD ZEPPELIN – “Your Time is Gonna Come” (Led Zeppelin)

Is it cheating to include this? I don’t think so. Imagine some guys sitting around, and one of them says, “Let’s form a Led Zeppelin cover band, but let’s do the songs reggae-style, and get an Elvis impersonator for our lead vocalist!” Good drugs, right? Well, Dread Zeppelin pulls it off with superb musicianship and a great sense of humor.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aNBFy4C8Vuc

BRYAN FERRY – “It’s My Party” (Leslie Gore)

Roxy Music’s lead singer put out his first solo album of cover songs in 1973, when his vocal style was still, shall we say, “mannered.” Nearly ten years later, Ferry’s smooth, melodic crooning on Avalon, Boys and Girls, and Bête Noire would earn him a large following. Note that he doesn’t bother to change the lyrics here to fit his gender.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X6fqDVe863o

Lone Star – “She Said, She Said” (The Beatles)

Despite the Texas reference, Lone Star was a Welsh hard rock band. Formed in 1976, they counted among their personnel guitarist Paul Chapman (a cousin of rocker Dave Edmunds), who would go on to join UFO. Here they give the Beatles track a spacy, heavy treatment.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jg7Dud55qlE

Monsoon – “Tomorrow Never Knows” (The Beatles)

Indipop (not Indie Pop) group Monsoon featured Sheila Chandra, a London-born singer of Indian descent. This album came out in 1982. She went on to record more traditional Indian music on the Indipop label as well as solo albums for Peter Gabriel’s Real World imprint.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VcER0OonPy0

Elton Motello – “I Can’t Explain” (The Who)

What a great name – obviously playing on Elvis Costello. Elton Motello (née Alan Ward) had a hit in 1977 with “Jet Boy Jet Girl” which, itself, was later covered by The Damned). The backing track for that song formed the basis of the international hit “Ça Plane Pour Moi” by Plastic Bertrand. Here, Motello goes full-on Devo with this cover of an early Who song.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xetXJvevz_M

Lone Star – “She Said, She Said” (The Beatles)

Despite the Texas reference, Lone Star was a Welsh hard rock band. Formed in 1976, they counted among their personnel guitarist Paul Chapman (a cousin of rocker Dave Edmunds), who would go on to join UFO. Here they give the Beatles track a spacy, heavy treatment.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jg7Dud55qlE

Monsoon – “Tomorrow Never Knows” (The Beatles)

Indipop (not Indie Pop) group Monsoon featured Sheila Chandra, a London-born singer of Indian descent. This album came out in 1982. She went on to record more traditional Indian music on the Indipop label as well as solo albums for Peter Gabriel’s Real World imprint.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VcER0OonPy0

Elton Motello – “I Can’t Explain” (The Who)

What a great name – obviously playing on Elvis Costello. Elton Motello (née Alan Ward) had a hit in 1977 with “Jet Boy Jet Girl” which, itself, was later covered by The Damned). The backing track for that song formed the basis of the international hit “Ça Plane Pour Moi” by Plastic Bertrand. Here, Motello goes full-on Devo with this cover of an early Who song.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xetXJvevz_M

Cyndee Peters – “House of The Rising Sun” (traditional - The Animals)

Cyndee Peters is an American-born gospel singer who has spent much of her life in Sweden. This compelling arrangement is from an album on the Swedish Opus 3 label, known for its minimalist approach to audiophile recording.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i-h3qqIbULE

Rabbitt – “Locomotive Breath” (Jethro Tull)

Hailing from South Africa, this was one of Trevor Rabin’s earliest outfits. He would go on to join Yes as part of their 90125 lineup, as well as composing film soundtracks. Rabbitt keyboardist Duncan Faure would later join the Bay City Rollers in their post-hit incarnation as The Rollers. Note the change in lyrics (“God” becomes “Charlie”).

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UdVYPzO9hUQ

Cyndee Peters – “House of The Rising Sun” (traditional - The Animals)

Cyndee Peters is an American-born gospel singer who has spent much of her life in Sweden. This compelling arrangement is from an album on the Swedish Opus 3 label, known for its minimalist approach to audiophile recording.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i-h3qqIbULE

Rabbitt – “Locomotive Breath” (Jethro Tull)

Hailing from South Africa, this was one of Trevor Rabin’s earliest outfits. He would go on to join Yes as part of their 90125 lineup, as well as composing film soundtracks. Rabbitt keyboardist Duncan Faure would later join the Bay City Rollers in their post-hit incarnation as The Rollers. Note the change in lyrics (“God” becomes “Charlie”).

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UdVYPzO9hUQ

Stewart & Gaskin – “Subterranean Homesick Blues” (Bob Dylan), “Levi Stubbs’ Tears” (Billy Bragg)

Dave Stewart (not of the Eurythmics) and Barbara Gaskin were veterans of the Canterbury progressive rock scene in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Stewart had played keyboards in quite a few bands, including Egg, Khan, Hatfield and the North, National Health, and Bruford. Gaskin was a singer with Hatfield, credited along with vocalists Amanda Parsons and Ann Rosenthal as “The Northettes.”

Stewart and Gaskin teamed up in the 1980s to produce three pop-oriented albums for the Rykodisc label, but had little success outside of England. Those albums featured a large number of cover versions, two of which are included here.

“Subterranean Homesick Blues” is given a very quirky rap/hip-hop treatment. At the start of the track, a quiet voice can be heard saying, “So, still no luck in the music business, eh guys?”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7MYgjgrZ8ts

Stewart & Gaskin – “Subterranean Homesick Blues” (Bob Dylan), “Levi Stubbs’ Tears” (Billy Bragg)

Dave Stewart (not of the Eurythmics) and Barbara Gaskin were veterans of the Canterbury progressive rock scene in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Stewart had played keyboards in quite a few bands, including Egg, Khan, Hatfield and the North, National Health, and Bruford. Gaskin was a singer with Hatfield, credited along with vocalists Amanda Parsons and Ann Rosenthal as “The Northettes.”

Stewart and Gaskin teamed up in the 1980s to produce three pop-oriented albums for the Rykodisc label, but had little success outside of England. Those albums featured a large number of cover versions, two of which are included here.

“Subterranean Homesick Blues” is given a very quirky rap/hip-hop treatment. At the start of the track, a quiet voice can be heard saying, “So, still no luck in the music business, eh guys?”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7MYgjgrZ8ts

Seeing as British singer-songwriter Billy Bragg is not exactly a household name, I’m including his original recording of “Levi Stubbs’ Tears” for comparison purposes. His is a stripped-down, demo-like track, typical of much of his recordings.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I4v8VJ0LRgA

The Stewart/Gaskin version is a complete re-imagining with a massive arrangement. These two versions make a great demonstration of what “production” means in recordings.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Df_yKtbu9Y4&list=PLQ0_3KQ4DZ-puuD5APHesVd_FE_HbVPxB

Of course, this is just a small sample of what’s out there (pun intended). If you have any favorites that I might want to include in a follow-up, please share them in the comments section.

Header image courtesy of

Seeing as British singer-songwriter Billy Bragg is not exactly a household name, I’m including his original recording of “Levi Stubbs’ Tears” for comparison purposes. His is a stripped-down, demo-like track, typical of much of his recordings.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I4v8VJ0LRgA

The Stewart/Gaskin version is a complete re-imagining with a massive arrangement. These two versions make a great demonstration of what “production” means in recordings.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Df_yKtbu9Y4&list=PLQ0_3KQ4DZ-puuD5APHesVd_FE_HbVPxB

Of course, this is just a small sample of what’s out there (pun intended). If you have any favorites that I might want to include in a follow-up, please share them in the comments section.

Header image courtesy of

Brandy Clark - Your Life is a Record

Brandy Clark may not be a household name to many other than country music fans, but she’s one of Nashville’s elite songwriters. A six-time Grammy nominee, she’s penned several number one hits on the country charts and several that have come very close to the top. And written for (and with) a litany of notable acts like Kacey Musgraves, Miranda Lambert, The Band Perry, Reba MacEntire, LeAnn Rimes, Toby Keith, and Sheryl Crow, among many others. She did her time on Nashville’s famed Music Row, cranking out the consistent hits in the early 2000’s for many of country music’s first-line acts. Your Life is a Record is her third album, and her often poignant and insightful songs are brought to life on a record that mostly seems less like dyed-in-the-wool country music. And more like a really good album by a great and upcoming singer/songwriter who’s reaching her peak.

Growing up in rural Washington state (Morton, population 900!), Brandy was steeped in traditional country music from the likes of Dolly Parton, Merle Haggard, Patsy Cline, Ronnie Milsap, and Dwight Yoakam. But she also explored the music of popular singer/songwriters, including James Taylor, Carole King, Mary Chapin Carpenter, and Randy Newman (who makes a guest appearance on the track “Bigger Boat”). She first picked up a guitar at age nine, dabbling with songwriting at the encouragement of her mother. Also a talented athlete, she received a full scholarship to play college basketball at Central Washington University. But eventually left to pursue her dreams of a life in music, when she moved to Nashville and enrolled in a music business degree program at Belmont College. She played in several local bands and in the college’s annual music showcase, and upon graduation, landed a job with a music publishing firm. Her talent as a performer was hard to conceal, and in no time she’d signed a publishing contract and quickly became one of Nashville’s go-to songwriters.

The album is a truly great listen; Brandy Clark has a great voice, and she sings entertaining, but literate and well-written songs that tell remarkably compelling stories. Many of them about her experiences in the music industry—it’s no wonder that she’s in such high demand as a songwriter in Nashville. But only on a couple of songs do you get the hard-sell impression that this is even a country album. The album is somewhat sparsely orchestrated, with only guitars, drums, bass, and keyboards, with strings and brass accompaniment brought in on a couple of songs for good effect. All my listening was done through Qobuz’s 24/48 high res stream, and the sound was sheer perfection. Highly recommended!

Warner, CD (download/streaming from Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Google Play Music, Apple Music, iTunes, Deezer, Spotify, Pandora, YouTube)

Brandy Clark - Your Life is a Record

Brandy Clark may not be a household name to many other than country music fans, but she’s one of Nashville’s elite songwriters. A six-time Grammy nominee, she’s penned several number one hits on the country charts and several that have come very close to the top. And written for (and with) a litany of notable acts like Kacey Musgraves, Miranda Lambert, The Band Perry, Reba MacEntire, LeAnn Rimes, Toby Keith, and Sheryl Crow, among many others. She did her time on Nashville’s famed Music Row, cranking out the consistent hits in the early 2000’s for many of country music’s first-line acts. Your Life is a Record is her third album, and her often poignant and insightful songs are brought to life on a record that mostly seems less like dyed-in-the-wool country music. And more like a really good album by a great and upcoming singer/songwriter who’s reaching her peak.

Growing up in rural Washington state (Morton, population 900!), Brandy was steeped in traditional country music from the likes of Dolly Parton, Merle Haggard, Patsy Cline, Ronnie Milsap, and Dwight Yoakam. But she also explored the music of popular singer/songwriters, including James Taylor, Carole King, Mary Chapin Carpenter, and Randy Newman (who makes a guest appearance on the track “Bigger Boat”). She first picked up a guitar at age nine, dabbling with songwriting at the encouragement of her mother. Also a talented athlete, she received a full scholarship to play college basketball at Central Washington University. But eventually left to pursue her dreams of a life in music, when she moved to Nashville and enrolled in a music business degree program at Belmont College. She played in several local bands and in the college’s annual music showcase, and upon graduation, landed a job with a music publishing firm. Her talent as a performer was hard to conceal, and in no time she’d signed a publishing contract and quickly became one of Nashville’s go-to songwriters.

The album is a truly great listen; Brandy Clark has a great voice, and she sings entertaining, but literate and well-written songs that tell remarkably compelling stories. Many of them about her experiences in the music industry—it’s no wonder that she’s in such high demand as a songwriter in Nashville. But only on a couple of songs do you get the hard-sell impression that this is even a country album. The album is somewhat sparsely orchestrated, with only guitars, drums, bass, and keyboards, with strings and brass accompaniment brought in on a couple of songs for good effect. All my listening was done through Qobuz’s 24/48 high res stream, and the sound was sheer perfection. Highly recommended!

Warner, CD (download/streaming from Amazon, Tidal, Qobuz, Google Play Music, Apple Music, iTunes, Deezer, Spotify, Pandora, YouTube)

King Crimson - Cat Food 50th Anniversary (Maxi Single)

King Crimson had enjoyed a remarkable level of success with their debut album, In the Court of the Crimson King, which charted at number five in England and number 28 in the USA. Not too shabby for a debut record, but the aftermath of the tour that followed the album’s release found the band in discord and disarray. Ian McDonald and Michael Giles split shortly after the tour’s conclusion, and Greg Lake was keen to join his future bandmates Keith Emerson and Carl Palmer in ELP. Lake was basically bribed to stay and contribute vocals to Crimson’s follow up album, In the Wake of Poseidon; if he stayed, he’d be given the band’s PA equipment as payment. The finished album, while stylistically similar to its predecessor, wasn’t quite as memorable and somewhat more muddled in its execution. Despite that, In the Wake of Poseidon managed to better the chart performance of In the Court of the Crimson King, landing at number four on the British charts and number 31 on the US charts. That said, ask most people to name a song from Wake, and most anyone will say “Cat Food.”

A heavily jazz-influenced ditty, “Cat Food” intros with a smooth walking bass line accompanied by some wildly stylistic piano playing from newest band member Keith Tippet. And soon segues into a howling guitar signature from Fripp; Greg Lake’s screaming vocal is just sheer perfection. The song is in such strong contrast to the rest of the album thematically, it just begs you to remember it above all the others, and showed how wildly creative King Crimson could be at their peak. Especially with a band that was essentially held together with some string and wires, and maybe a bit of studio trickery.

Qobuz has been rolling out a series of King Crimson maxi-singles over the last year or so; the band hasn’t (until recently) authorized much in terms of full catalog albums for release on any of the streaming sites. Thankfully, that’s been mostly rectified, but the maxi-singles still have a considerable amount of interest to the collector or die-hard Crimson fan. The four songs here compile three different versions of “Cat Food,” including the 45 rpm single release, a live version of unknown provenance (but sounding very good, and very much from the era of the album release), and of course, the album version of the song. But the really compelling reason to check this music out is the instrumental fourth song, “Groon,” which was the “B” side of the “Cat Food” 45, and has basically taken on a life of its own in King Crimson lore. For years, unless you happened to have the 45, you didn’t have access to “Groon,” and you maybe never heard it until much later in King Crimson’s career, when it popped up on an occasional Japanese compilation LP or CD. And eventually much later as a bonus track on the 30th and 40th anniversary releases of In the Wake of Poseidon.

The version of “Groon” that appears here is the three and a half minute original take; divinely inspired Crimson madness, with some remarkable guitar work by Robert Fripp and Michael Giles’ (who returned only as a hired gun and not a member of the band) superb, jazzily-animated drumming. And the song seems to end about four times, only to have Fripp and Giles kick back in maniacally and repeatedly until the tune’s close. It’s simply breathtaking! If you have a Qobuz account, it’s well worth checking out, and is also available from British label Panegyric as a CD and 10-inch single.

Discipline Global Mobile/Panegyric, CD/10-inch single (download/streaming from Qobuz)

King Crimson - Cat Food 50th Anniversary (Maxi Single)

King Crimson had enjoyed a remarkable level of success with their debut album, In the Court of the Crimson King, which charted at number five in England and number 28 in the USA. Not too shabby for a debut record, but the aftermath of the tour that followed the album’s release found the band in discord and disarray. Ian McDonald and Michael Giles split shortly after the tour’s conclusion, and Greg Lake was keen to join his future bandmates Keith Emerson and Carl Palmer in ELP. Lake was basically bribed to stay and contribute vocals to Crimson’s follow up album, In the Wake of Poseidon; if he stayed, he’d be given the band’s PA equipment as payment. The finished album, while stylistically similar to its predecessor, wasn’t quite as memorable and somewhat more muddled in its execution. Despite that, In the Wake of Poseidon managed to better the chart performance of In the Court of the Crimson King, landing at number four on the British charts and number 31 on the US charts. That said, ask most people to name a song from Wake, and most anyone will say “Cat Food.”

A heavily jazz-influenced ditty, “Cat Food” intros with a smooth walking bass line accompanied by some wildly stylistic piano playing from newest band member Keith Tippet. And soon segues into a howling guitar signature from Fripp; Greg Lake’s screaming vocal is just sheer perfection. The song is in such strong contrast to the rest of the album thematically, it just begs you to remember it above all the others, and showed how wildly creative King Crimson could be at their peak. Especially with a band that was essentially held together with some string and wires, and maybe a bit of studio trickery.

Qobuz has been rolling out a series of King Crimson maxi-singles over the last year or so; the band hasn’t (until recently) authorized much in terms of full catalog albums for release on any of the streaming sites. Thankfully, that’s been mostly rectified, but the maxi-singles still have a considerable amount of interest to the collector or die-hard Crimson fan. The four songs here compile three different versions of “Cat Food,” including the 45 rpm single release, a live version of unknown provenance (but sounding very good, and very much from the era of the album release), and of course, the album version of the song. But the really compelling reason to check this music out is the instrumental fourth song, “Groon,” which was the “B” side of the “Cat Food” 45, and has basically taken on a life of its own in King Crimson lore. For years, unless you happened to have the 45, you didn’t have access to “Groon,” and you maybe never heard it until much later in King Crimson’s career, when it popped up on an occasional Japanese compilation LP or CD. And eventually much later as a bonus track on the 30th and 40th anniversary releases of In the Wake of Poseidon.

The version of “Groon” that appears here is the three and a half minute original take; divinely inspired Crimson madness, with some remarkable guitar work by Robert Fripp and Michael Giles’ (who returned only as a hired gun and not a member of the band) superb, jazzily-animated drumming. And the song seems to end about four times, only to have Fripp and Giles kick back in maniacally and repeatedly until the tune’s close. It’s simply breathtaking! If you have a Qobuz account, it’s well worth checking out, and is also available from British label Panegyric as a CD and 10-inch single.

Discipline Global Mobile/Panegyric, CD/10-inch single (download/streaming from Qobuz)

Charlie Parker - The Savoy 10-Inch LP Collection

The Savoy 10-Inch LPs that Charlie Parker recorded from 1944 to 1948 are among the cornerstones of his work, and contain some of his finest and most inspired playing on record. Bird was one of—if not the—most influential sax player(s) of all time; his amazing work set the standard for everyone who would follow. And he was surrounded on these sessions by the likes of Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, John Lewis, Bud Powell, and Max Roach—could it possibly get any better? Good luck trying to find—or possibly trying to get financing—for mint originals.