I’ve been reviewing the autobiographies of many of the producer/engineers who are responsible for a great many of the records that Copper readers and music fans around the globe have loved for over the past three quarters of a century. It’s been an enlightening journey. The evolution of the recording studio has paralleled the development of audiophile listening equipment, and the people responsible for capturing those artistically-resonant musical moments that many of us cherish deserve their accolades.

I’ve reviewed books by Geoff Emerick, Al Schmitt, and Bill Schnee (in Issue 161 and Issue 160). While they have all made incredible records and contributions to recording techniques, Phil Ramone (1934 – 2013), founder of A & R Recording in New York, not only has had his recordings find their way into the music libraries of millions, but he was also responsible for pioneering numerous innovations in sound reinforcement for Broadway theaters, outdoor concerts, White House speeches, and in the recording of live theatrical and movie soundtracks. These advancements have become standard practice in the industry – an embarrassingly revelatory discovery for me, who had followed Ramone’s work with Billy Joel, Bob Dylan, the Band, and Paul Simon, among others, but was previously unaware of his other monumental achievements..

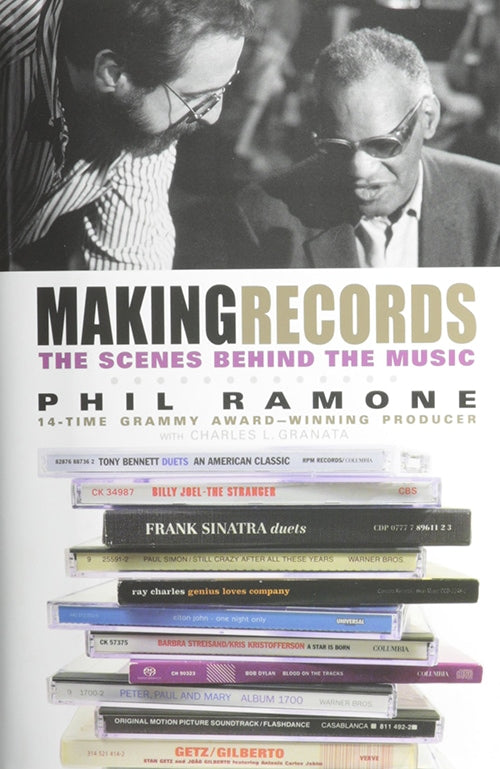

Making Records: The Scenes Behind the Music discloses many of the historical events that led to Phil Ramone’s reputation as the sonic wizard who could solve any audio obstacle. The book reveals a good deal of his acoustic engineering methods, his philosophies about music and audio, and some humorous anecdotes about the music industry.

Phil Ramone. Courtesy of Clyne Media.

Crediting Bill Putnam, Tom Dowd, John Hammond and others as mentors, Ramone’s early training as an assistant engineer included working with Tom Dowd in recording some of the 4-track earliest experiments of the harmolodic double jazz quartets of Ornette Coleman and Eric Dolphy. Their open-ended and extended improvisations forced the young engineer to think on his feet and be ready to cue up a back-up 2-track machine in order to continue recording and not miss a note of the performances as the 4-track tape ran out. Ironically, Ramone noted ruefully in the book that such preparedness is often lacking today due to the ubiquity of digital audio workstations (DAW), where longer recording times are taken for granted. When producing Slash on analog tape at Electric Lady Studios, an assistant engineer started rewinding a tape according to company policy, before loading a fresh reel of tape, during an extended Slash solo, thus losing the opportunity to capture the lightning in a bottle magic that had inspired what Ramone described as some of “Slash’s finest playing ever on that song.”

This early education in preparedness and in improvising solutions served Ramone in good stead as he put his lessons to the test when he launched A & R Recording in the 1950s. Working with producers like Quincy Jones led to Ramone’s burgeoning reputation, and subsequently working closely with many top artists. Notable landmark projects from that era include:

- Elton John, whose live trio album,11-17-70 was recorded at and broadcast live from A & R.

- Dionne Warwick: “What the World Needs Now,” “I Say a Little Prayer,” “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again,” “Alfie,” and “Do You Know the Way to San Jose?” were all engineered by Ramone at A & R.

- Ramone engineered the landmark Getz/Gilberto album for producer Creed Taylor at A & R, the album that included “The Girl From Ipanema” and put bossa nova on the map in the US.

Ramone would also work with Frank Sinatra, Barbra Streisand, Ray Charles, Tony Bennett and many others, in addition to his standout projects with Paul Simon and Billy Joel.

Ramone’s early years in learning how to create acoustic “spaces” and generate and control echo, delay and reverb took place under the tutelage of engineer Bill Schwartau. This experience would become invaluable in Ramone’s later work, which would confound acoustic theory scholars who were trained according to orthodox accepted methods, and then stumped at how Ramone transformed his mad-scientist approaches into state-of-the-art sound systems.

Phil Ramone realized early on that the ability to control echo and reverb was a very strong selling point for independently-owned A & R Studios. In the book, he goes into technical detail regarding his discovery of how to properly tune EMT plate reverbs, and his subsequent investment into additional EMT units, which caused the number of his recording projects to snowball. A & R’s reputation for excellent sound spread throughout the music and jingle industry in New York.

A & R Studio’s midtown Manhattan address also situated Ramone in an ideal location to become a go-to solution provider for film sound and Broadway theater sound recording and performance, leading to his work on such projects as Liza With a “Z,” A Star is Born, Yentl, Flashdance, Midnight Cowboy, and many others.

An accomplished musician and engineer in his own right (he engineered all of his projects up to and including Billy Joel’s The Stranger), Phil Ramone’s creative instincts drew him more and more towards producing, which he likened to a combination of “friend, cheerleader, psychologist, taskmaster, court jester, troubleshooter, secretary, traffic cop, judge, and jury rolled into one.”

While Ramone goes into fascinating details about the making of such iconic albums as Paul Simon’s Still Crazy After All These Years and There Goes Rhymin’ Simon, Billy Joel’s The Stranger, 52nd Street, The Nylon Curtain and The Bridge, Paul McCartney’s Ram, and Bob Dylan’s Blood On The Tracks, he also cites lesser-known records of personal sentimental value, such as the overlooked and underrated Karen Carpenter solo album (released 13 years after her death), or Julian Lennon’s Valotte, equally valid musically, although significantly less critically acclaimed.

Far less publicized but historically momentous are Phil Ramone’s innovations for sound reinforcement and theatrical sound, and subsequent methods he put into place for recording original cast albums..

As A & R Recording’s reputation grew, Ramone and partner Don Frey received so many requests for concert and television production sound that they got on the radar of the White House in 1961. This led to A & R being asked to work on the atrocious acoustics at the Washington D.C. National Guard Armory and remedy the problems before a scheduled broadcast of a President John F. Kennedy speech and National Symphony Orchestra performance.

Improvising a jerry-rigged speaker system he devised with Altec to be hung in tiers, and an ingenious use of 10,000 experimental NASA weather balloons loaded with Styrofoam to dampen the Armory’s cavernous echoes, Ramone humorously recounts that he received a 7 am phone call from President Kennedy following the event. Kennedy was calling Ramone to congratulate him and Ramone hung up, thinking it was a practical joke. He then profusely apologized when JFK called back, laughing and explaining that it was really him.

The triumphant success with the Armory sound solution led to Ramone creating the acoustic design and the recording system for the East Room at the White House. His design has since become standard. As the go-to sound person for President Kennedy, it would fall upon Ramone to oversee sound for the historic Madison Square Garden event highlighted by Marilyn Monroe singing “Happy Birthday” to JFK in May 1962.

New York City concerts in Central Park have been a standard summer event for over 50 years, but it was Phil Ramone who set the bar for acoustic engineering design and for sound quality. In 1967 he was introduced to Barbra Streisand after he was approached by her manager, Marty Erlichman, to design a sound system for a first-time-ever concert in Central Park’s 99-acre Sheep Meadow, for a live album recording and CBS-TV broadcast videotaping. With an anticipated attendance of 10,000, Ramone was given the unprecedented task of creating an open-air sound system that would allow listeners to hear the music clearly thousands of feet away without any time delay.

The fixed, frequency-limited sound systems then used in open arenas like Yankee Stadium were inadequate to meet the needs for high-quality live and recorded sound quality. In addition, the sound system would have to be assembled for the concert and then torn down afterwards to restore Central Park to its normal environment.

With mad scientist aplomb, Ramone put on his creative thinking cap and conjured up the following solutions:

- Creating a series of 12 speaker towers that utilized then-experimental JBL long-throw horns to mitigate delay issues for the listeners farthest from the stage.

- Hiring an air-conditioned trailer to keep the humongous power amps needed for the sound system from overheating.

- Taking out a rain insurance policy from Lloyd’s of London.

At one point a lighting truck accidentally severed a large cluster of microphone cables, and a six-man team had to splice them back together.

A mobile multi-track recording truck was hired, but Ramone wound up having to oversee the recording himself, as the assistant who came with the truck was drunk, and passed out before the show had begun.

The resulting record, A Happening in Central Park, went gold, and the broadcast received great acclaim. It was released on home video in the 1980s, and subsequently on DVD and Netflix. The attendance for the concert totaled around 125,000, 12 times more than initially anticipated.

In 1981, Ramone was called in to replicate his Central Park sound reinforcement conquest and take it up several notches when Simon and Garfunkel decided to hold a reunion concert, to be recorded for an album and televised. Expanding upon his earlier efforts, Ramone accommodated for the larger anticipated crowd, and the 500,000 concert attendees were enthralled. This historic event was a huge success, and both the record album and DVD became best sellers.

While Phil Ramone’s work on movie soundtracks makes for quite an extensive list, his pioneering work in surround sound is worth noting.

The book has a fascinating breakdown of the intricate system that Ramone devised to record the live music performances while filming the 1976 version of A Star Is Born, which featured the mammoth single, “Evergreen.” Streisand wanted music and vocals to be recorded live on the movie sets and then transmitted through 60 Class-A phone lines between The Burbank Studios and Todd-AO’s facilities. (Class A telephone lines are normally used for official government business.) Ramone would have to mix the music and then send it over the phone lines, and Streisand would later supervise the assembling of the dialogue, music and sound effects. This necessitated the first-ever use of experimental satellite technology developed by Pacific Bell, and resulted in the first magnetic Dolby Stereo surround-sound film, which premiered in true surround sound in 15 theaters throughout the US. Dolby Stereo encoded four channels of surround information – left, right, center and surround – onto a 2-channel format.

Ramone’s insights into original cast Broadway recordings are particularly enlightening. Unlike a studio recording, Ramone viewed doing an original cast soundtrack album as capturing a piece of history, since Actors’ Equity rules are strict with regard to recording a show for commercial purposes. As a result, his approach was more akin to doing a live radio broadcast than creating a meticulously recorded and mixed Paul Simon or Billy Joel album.

Ramone’s original cast recordings involved recording entire run-throughs and two additional full takes, expanding the pit orchestra to enrich the sound, and placing the actors at the back end of the studio so they had room to use their bodies while singing in order to capture the same energy that they exhibited on stage. Rather than rein in actors from projecting their voices the way they did on stage, Ramone would use microphones that wouldn’t distort when the actors were singing loudly, in order to allow the actors to replicate their stage performances as closely as possible.

When Phil Ramone produced Promises, Promises in 1968 (his first Broadway original cast recording, for which he won a Grammy), he was approached by composers Burt Bacharach and Hal David to redesign the acoustics of the Shubert Theatre to better approximate the pristine sound of the pair’s past recordings with Dionne Warwick and Dusty Springfield as Ramone had engineered them.

Adapting a new process of measuring and analyzing acoustics called Acousti-Voicing for its first-ever use inside a theater, Ramone and his partners charted the frequency response at different areas within the room. They then designed a speaker placement system to create the illusion that the sound was coming from the stage. The audio system incorporated as many as 24 amplifiers, 180 microphones, 18 Altec speakers, a custom-built Langevin broadcast console, graphic equalizers, and Ramone’s standby EMT reverb plate. Additionally, the orchestra pit was reconfigured with an added ceiling, plus sound baffles separating different orchestra sections, and space for a vocal group.

The Shubert Theatre’s transformation via a radical combination of studio equipment, acoustic analysis, and then-primordial surround sound stymied professional acousticians, but the results were state-of-the-art, and soon became the benchmark upon which most professional theatrical sound is currently predicated.

Taking things a step further, Ramone would go on to fabricate the first seamless technical combination of studio-recorded and live theatrical sound for film with the 1972 Liza Minnelli television special Liza With a “Z.” Choreographer Bob Fosse wanted live vocals instead of pre-recorded songs to accompany the intricate dance routines, as he was concerned that camera close-ups on Liza would reveal lip-synching.

Ramone solved the problem by utilizing a wireless radio microphone hidden in Minnelli’s skimpy Halston dress, with the plan for her to only lip-synch during the strenuous dance sections while singing live for the rest. Expertly fading the pre-recorded track in and out, he was able to fool Fosse from differentiating between the live and recorded vocals, and Liza With a “Z” would go on to win four Emmy awards and a Peabody award.

Phil Ramone begins and ends Making Records – The Scenes Behind The Music with a tribute to his musical idols, and the personal delight he took in producing some of their iconic records during the twilight of their careers. He recounts the blow-by blow-events and emotional upheavals in the making of Duets with Frank Sinatra, and Ray Charles’ Genius Loves Company.

The pugnacious and acerbic Sinatra had become thoroughly entrenched in his ways and was a notorious curmudgeon by 1990. The 1993 recording sessions for Duets began against a backdrop of historical baggage: the recording would be for Capitol, the label Sinatra parted acrimoniously from back in 1962. Sinatra refused to record without a 55-piece live orchestra playing, with any notion of recording with a smaller ensemble immediately rejected. There was concern from Ramone and engineer Al Schmitt that even the suggestion of an overdubbed vocal could invite a physical attack. Duets would mark Sinatra’s return to the studio after nearly 10 years. And while reluctant to redo his old hits as duets with younger singers, he also, unlike Tony Bennett for example, steadfastly refused to sing with them in the studio.

Upon making Sinatra comfortable by repositioning him with the orchestra instead of in a vocal booth, Ramone finally got him to agree to record by promising him, “If you’re unhappy with what we do, I’ll personally erase the tapes. No one will ever hear them. Don’t worry – this will be great!”

Sinatra’s response: “it better be.”

The recording of Ray Charles’ Genius Loves Company, which became his last and biggest-selling record, took a 180-degree opposite approach. Charles insisted that the duets be done live with the guest artists in the same room.

Due to his blindness, Charles was most comfortable recording in his own studio, built in 1964, where he could navigate all the rooms from memory. He even knew the console well enough to do mixes himself. Yet, Charles was not only able to record Genius Loves Company in an unfamiliar studio, he would point out to Ramone when a tempo was off by a single beat per minute.

Both records featured timeless collaborations between the two music legends and the stars who grew up on their music, including Natalie Cole, Elton John, Bonnie Raitt, Stevie Wonder, Norah Jones, Barbra Streisand, Aretha Franklin, and many others. The stories of the making of both albums are fitting bookends to a captivating read for anyone interested in Phil Ramone’s sometimes-unsung contributions to music, recording and live sound.