There are so many in-ear monitors (otherwise known as IEMs, earbuds, earphones, or in-ear headphones) in the marketplace, how can one navigate the minefield of IEMs which are out there? How can we determine what a set of in-ears may sound like before buying a new item, rather than hitting and hoping and perhaps ending up with an unduly heavy slice of buyer’s remorse? In this short series we hope to assist in making better informed choices. (The first installment appeared in Issue 180.)

Thanks to the abundance of online reviews and albeit sometimes biased opinions, there exists a large amount of information as to what may sound good. Given that there has been such massive growth in the headphones and IEM space since 2012, by now we should be able to experience a known, great-sounding product without too much hassle. Yet a 2017 article written by Jeroen Breebart for The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America (ASA) titled “No Correlation Between Headphone Frequency Response and Retail Price” noted the disconnect between the two factors.

In other words, you don’t always get what you pay for. That said, it is also possible to get far more than what you used to pay even a few years ago thanks to intense competition.

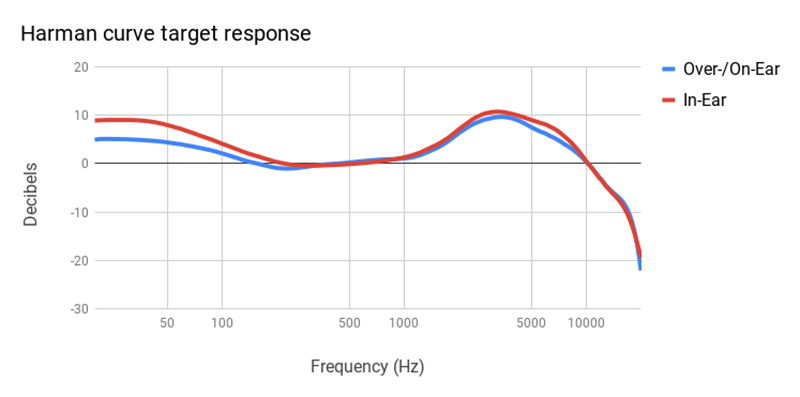

How may us lowly mortals benefit from modern technology advancements? We mentioned the “Harman curve” in the last installment. This is a frequency response curve determined by Harman to be pleasing to a majority of listeners.

The engineers at Harman addressed the issue of inconsistency in the frequency response of headphones. Many headphones delivered tubby bass and harsh treble. Who could help sweep away this sonically-muddied state of affairs? One exemplary engineer, Harman’s Dr. Sean Olive, set his sights on designing products that not only would compete with the then -super-popular Beats headphones by Dr Dre, but improve on them. Why? The tenacious Dr. Olive was not content to simply replicate Beats models (and perhaps gain an equal share of the marketplace), but instead pushed the necessity to find the audio parameters that would deliver the best listening experience. Harman had already done this for loudspeakers, thanks to the research and industrious subjective and objective testing performed by Olive’s colleague, Dr. Floyd Toole.

Part of Harman’s efforts of seven years of intensive headphone analysis from 2012 to 2019 encompassed subjective testing of both trained and non-trained listeners, including American, Canadians, Chinese and Europeans. This resulted in the creation of the Harman curve. This is a huge oversimplification of the development and testing that came to produce this outcome, which is a well-respected and generally-accepted good fit for most listeners. The Harman curve’s resultant frequency response provided a preferred listening experience for 64 percent of the tested listeners, with the remaining split falling at 21 percent to those who enjoyed a less bass-rich sound and 15 percent preferring a significantly more bass-emphasized experience.

Additionally, this showed that no matter where you are from in the world, you are likely to be more similar than different to most people in your listening preferences. Growing up, I always enjoyed more of a treble-emphasized and detailed sound, and I wondered if this was more to do with a genetic or nationality-related thing, or just simply personal preference at that age. It turns out to be the latter, as the studies revealed that as humans we tend to enjoy music in a manner which is more universally the same than may have been initially considered to be the case.

How can the Harman curve help us? Harman’s delta between on- and off-target frequency responses is graphed as an error curve. The flatter the error curve, the less deviation from the target. This is really helpful because it’s such an easy visual reference to interpret. If, however, you are just comparing an overlaid target curve with a given IEM’s headphone’s frequency response, here are some pointers which may help you examine what you are looking at.

Measurements aside, It’s important to keep in mind what you personally prefer in steering your ultimate choice. If you like headphones that are warmer in the bass than what is “accurate,” that’s OK, and you can use measurements accordingly to make both initial visual and audible comparisons. Ask yourself: do I like a clear midrange with no bass “bleed” into those mids above 200 Hz? Or I might prefer a slightly warmer sound, with a darker tonality with a boosted bottom end. Do I like a more detailed presence for female and male vocals? How much top end detail do I like to hear that is refined, yet not brittle and fatiguing? Yes, ultimately it does boil down to physically trying out the in-ear headphones you intend to buy, but you can certainly slough away a huge slice of rubbish-sounding products simply by looking at their frequency response curves (if available) compared to the Harman curve.

When I was considering which in-ear headphone to buy next, I had the following prerequisite: it had to have a good physical fit to eliminate bass leakage. In some of the subjective listening tests conducted by Harman, when evaluating one particular model of headphones approximately half of the listeners said the bass sounded great, and the other half reported than the bass sounded like it was missing, when the measurements revealed that the unit did indeed have significant bass response. What was happening? Some listeners experienced bass leakage resulting from a poor seal to the ear. A good seal is critical to prevent bass rolloff, up to 500Hz. (Incidentally, if you haven’t tried them, the Comply Foam earphone tips are a great solution for a truly snug and bass-sealed fit as they gently expand to fill your outer ear canal.)

To that end I considered the Etymotic Research ER2SE Studio Edition IEM (SRP: $99.99 - $109.99. They are deep-fitting in-ears which are not going to fall out, and have a super snug fit. I know some people may find these invasive and uncomfortable, but since I had been using similarly close-fitting earplugs for riding my bike and felt comfortable with them, I knew this probably wouldn’t bother me. In fact, citing the ER25SE as offering a focused and engaging listening experience is not surprising, given their physically deep fit and claim for studio-grade accuracy. ER Series IEMs are available in a number of variations including an extended-bass-response model, the ER2XR. Like the ER25SE, it also fits deeply into the ear canal – great for blocking external noise by the way.

Check out the error curve on these JBL Endurance RUN headphones:

https://www.audiosciencereview.com/forum/index.php?threads/jbl-endurance-run.39901/

The Endurance RUN has a small error curve of 1.24, and a corresponding predicted listener preference of 84.68 percent.

Alternatively, why not consider the go-to choice of Dr. Sean Olive himself: the JBL CLUB Pro+ TWS. These wireless noise-cancelling headphones are even closer to the Harman target curve with an average error curve of just 1.02 and a predicted preference of 88.22 percent. These have an SRP of $199.95 could very well be your “home run” IEM.

These do have active noise cancellation, which is great for the most part, but there is one caveat to bear in mind. The limitation of ANC is that it is most effective only in certain bass frequency ranges and as such, we asked Dr. Sean Olive about these characteristics. He replied:

“While it is true that ANC is most effective below 1 kHz, an in-ear headphone uses passive attenuation above that frequency to effectively offer a relatively flat noise attenuation across the entire frequency band. Compare that to, say, the passive attenuation of the ER2X which has ~35 dB of attenuation above 1 kHz and very little (10 dB) at lower frequencies. From a sound quality view, I would argue it’s better to have constant attenuation across the bandwidth than uneven attenuation that is very frequency-dependent. When you consider that JBL’s TWS headphones with ANC

Header image: woman wearing Audio-Technica ATH-CKS5TW in-ear headphones. Courtesy of Audio-Technica U.S., Inc.