After recently interviewing Scott Newnam of Audio Advice (Issue 161 and Issue 160), I reflected on the answers to one of the questions I had asked him:

What question do audiophiles very rarely consider that they should?

Newnam answered: “As audiophiles we often get too caught up in the specifications and measurements. Ultimately, what we want is fabulous sound. As we get older, we might need an increasingly less-flat response curve from our system to achieve the perceived sound that was intended and that we enjoy. So, don’t be afraid to test adjustments that might theoretically produce slightly too much bass or high frequencies if the result sounds better to you.”

His response, combined with the fact that I had previously experienced personal hearing issues, prompted me to do something about addressing my own limitations. It’s true that hearing loss is a very personal thing, and relative to every individual in terms of its significance and degree of severity. But, if you can make improvements to what your perception is, and perhaps more effectively enhance or compensate for which areas of your hearing have been reduced, then surely the first part of the process is to identify what is adversely affected.

I was aware that I had lost some treble sensitivity over the years, particularly in my right ear, not least of all due to a lifetime (so far!) of listening to music, owning and running a guitar shop, attending gigs, and, like all of us, being subject to the vagaries of aging. I distinctly remember being in my guitar shop and in one ear hearing the blaring tones of Marshall 100-watt stacks being put through their paces by over-zealous potential future rock stars, while at the same time trying to decipher conversations on the phone with my other ear! I also remember testing a Mesa Boogie Mark IV combo after it had been returned from the amp technician, and witnessing the expression on his face when it was truly cranked. (It was only for a very short time.) It was necessary to test gear at volume for regular gigging use. (The Mark IV is a great-sounding guitar combo! Especially when loaded with a Celestion “Greenback,” compared to the very-bright-sounding 200-watt Electro-Voice speaker versions. I like both for different reasons; the Celestion for rich warm harmonics and mid-tones which suit blues and rock, whereas the E-V has more of a harder edge and crisp crunch to distorted sounds and is a brand often known for PA installations.)

The ability of human hearing to handle such a dynamic range (roughly 120 dB) truly is remarkable, even if our ears are subject to wear and tear! I have always been a bit of a self-confessed treble head. I just love the definition and articulation in upper-register detail; crunch, snappiness and liveliness in well-voiced snares and hi-hats, for example. Don’t get me wrong – I’m also a bass-head who appreciates everything the low end does to enhance the midrange and listening spectrum in general, but I do love top-end clarity and “harder” definition a little more than most. There’s something truly special about listening to a drummer with real bite, playing a beautifully tuned kit. Neal Peart, Gavin Harrison, Keith Carlock, Simon Phillips, Steve Gadd, Terry Bozzio, Vinnie Colaiuta, Buddy Rich, Mike Portnoy, Nick D’Virgilio and Virgil Donati immediately spring to mind. Their talents and feel are just humbling to behold. Here’s a Keith Carlock solo from the 2005 Modern Drummer festival which is truly stunning:

Back to the subject of dealing with your personal hearing loss, and how it may be impacting your own listening: what can help point you in the right direction if you are either suspicious of having hearing loss, or want to confirm that there is in fact something going on?

You may (or may not) be surprised to learn that there are a variety of audio-enhancement software programs built into many modern Android- and Apple-based phones and tablets, which can offer surprisingly good improvements when listening with earbuds or headphones. Perhaps the greatest value of such software, though, is in identifying the extent of the problems you may have that you were perhaps initially unaware of. Hearing loss tends to happen gradually, unless, of course, as a result of some high-level exposure for a damaging period of time.

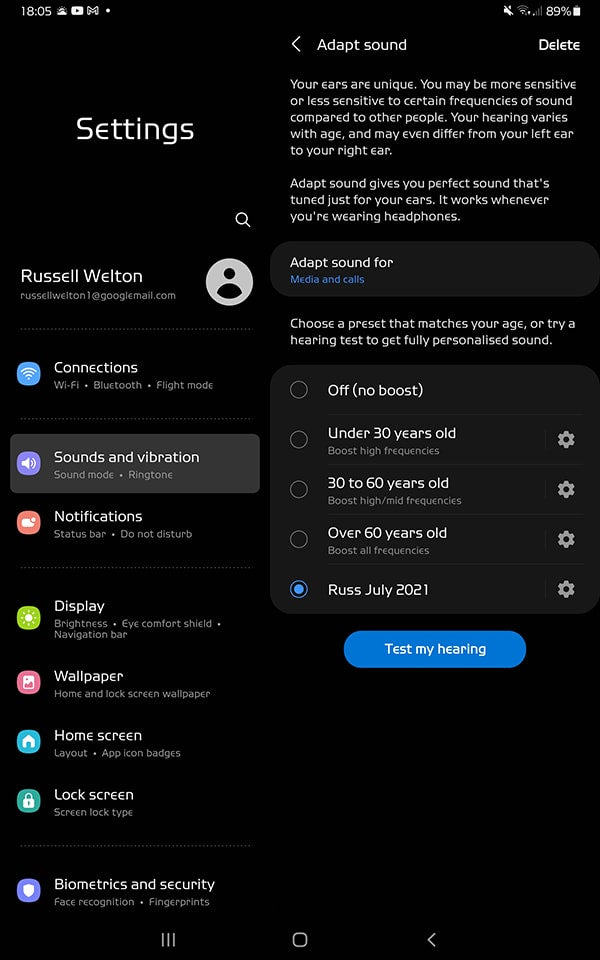

To name one example: the Samsung Android operating system built into my tablet has a useful feature called Adapt Sound. Under the Settings menu – Sounds and Vibration – then Sound Quality and Effects is a menu entitled Adapt Sound which allows you to run a basic hearing test. You must plug in your headphones for the program to run. It will then play a series of beeps at different volume levels for each respective ear, and you respond affirmatively when you hear the beep by tapping the screen. It’s simple but very insightful, and portrays the result of your test results in a graphic EQ style with the areas of reduced hearing shown in pale blue, and conversely, what you should expect to be able to hear by turning on Adapt Sound shown in dark blue.

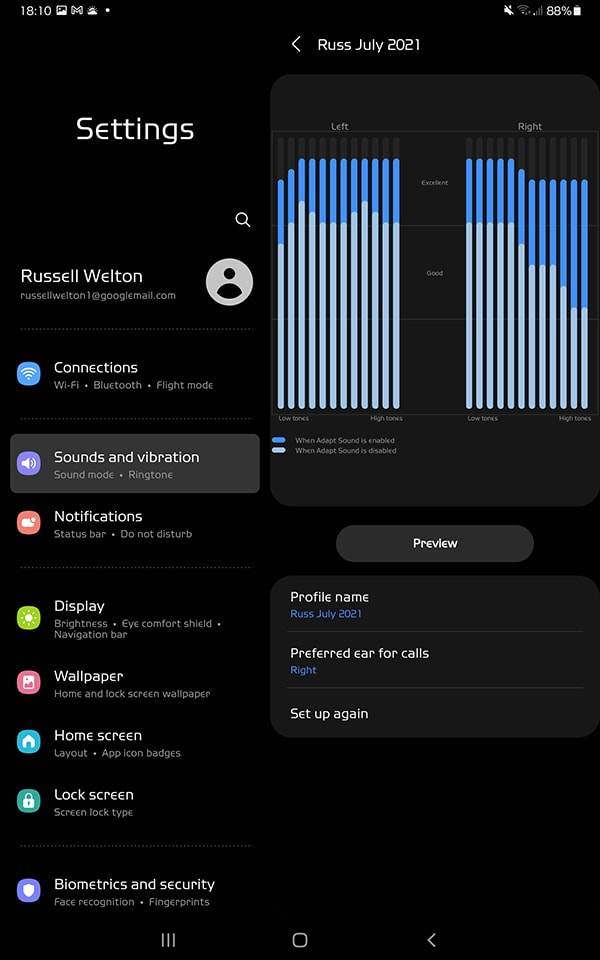

There is a choice of available Adapt Sound settings. The first is Off, with no boosts to any frequencies. The Under 30 Years Old setting boosts higher frequencies. The third preset is the 30 to 60 Years Old option, which will boost high and mid frequencies. Fourth is the Over 60 Years Old preset, which increases all frequencies but just not quite as much as in the upper treble range settings for the Under 30 Years Old mode. If you run the hearing test and save your own personal profile, you may then make a comparison between the graphic displays of the different-age presets and your own result, which will guide you in picking the best setting for your needs. My personal result is closest to the Over 60 Years Old in my right ear but within the 30 to 60-year-old group for my left.

Adapt Sound app menu.

Adapt Sound app showing measurement results.

Although I don’t own an Apple phone or device, I was able to find a function called the Apple Headphone Safety Report which may be found under the Headphone Safety menu. It is designed to protect your hearing by measuring your cumulative exposure to given audio levels, and if you exceed the limit that is recommended within a week, you will receive a notification, and in true Apple style, the feature takes control and turns the volume down. It also has a Reduce Loud Sounds mode. This analyzes your headphone audio and will similarly reduce the volume above a preset dB threshold. Perhaps the results will provide motivation for a further test with an audiologist.

So, I decided to do just that. Some time ago I had developed vertigo symptoms and balance issues, and had some remaining hearing impairment. At first I thought that perhaps it was congestion from an infection, but it wasn’t. Perhaps it was some form of labyrinthitis? The symptoms had reduced in their severity after a period of weeks after I first felt ill, but I was still experiencing some sense of inner-ear pressure. I needed to see a professional. I went to an audiologist.

The audiologist’s initial tests included a basic, press-the-button-when-you-hear-a-signal test, followed by a repeat of the same test but with an overlaid noise (it sounded like a pattern of dithered static) which partly obfuscated the test tones. Like me, perhaps you’d then recognize just how much of your hearing is actually calculated by the brain as you interpret the impulses. The overlaid noise signal is played at slightly varying volumes, as are the test tones, and you can’t help but anticipate what you think the correct response timing is – when in fact you are not so sure.

The test is conducted over a relatively partial slice of the audible spectrum, and when examining my results, I discover that the test tones were played at 250 Hz, 500 Hz, 1 kHz, 2 kHz, 3 kHz, 4 kHz, 6 kHz and 8 kHz, useful but not what you might consider extensive. The range primarily covers what is important for detecting conversation, plosives (sounds that are associated with saying the letters p, t, k, b, d and g), and other consonants.

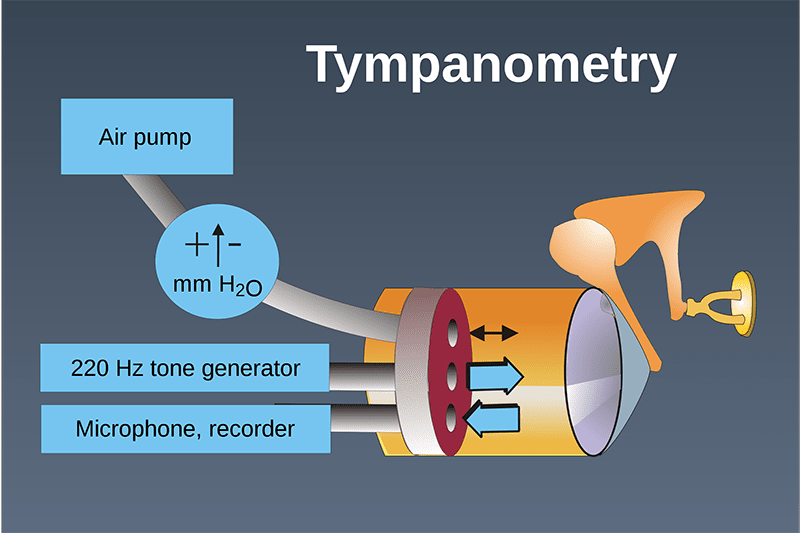

The third test involved a tympanic membrane measurement, obtained from sensing the tension on the eardrum by pulsing a short blast of air down the ear canal. After determining that the results of this test were perfect and that my loss of sensitivity was due to some inner-ear cochlear issue, I was surprised to then be issued with hearing aids. I was gobsmacked but grateful. In my naivete I had expected to be given a prescription for something for inflammation, or be told to turn the volume down in the car when listening to music, or something along those lines, but alas, no! My hearing loss was real, albeit not as impactful as it could have been.

Diagram of a tympanometry, or tympanic membrane, test. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Scott Martin.

After being tested a second time about three months later, I’d had some mild further improvement, so perhaps some inflammation or congestion had in fact played a part. The doctor told me I was probably more attuned to listening to sounds more carefully than before, because I was paying more than the usual attention to what I was hearing (or not), but I disagree. My sense of excessive inner-ear pressure was very real and still remains, though to a lesser degree.

The moral of the story for me: look after the hearing you do have. It may sound obvious, but the reality is that hearing damage may happen gradually without your (at first) conscious awareness, particularly if you are a musician who is gigging regularly, or someone who is subject to prolonged periods of exposure to volumes above approximately 85 dBA.

Food for thought is provided in the film Sound of Metal, starring Riz Ahmed as Ruben Stone, a punk metal drummer who loses his hearing. The film covers Stone’s journey, and those around him, of coming to terms with the losses in his life. It may be sobering, but the film will perhaps make you appreciate your hearing, and the need to preserve it, more than ever before.

Header image courtesy of Pexels.com/RODNAEProductions.