Artistic geniuses at a young age are not entirely uncommon, as prodigies from Mozart to Derek Trucks bear witness. When the Beatles broke out with their first record in 1962, John Lennon and Ringo Starr were 22, Paul McCartney was 20, and George Harrison was 19. As burgeoning pop stars, youth was part of the job description.

Such was not the case with sound engineers, especially in England during the 1960s. Looked upon as a technical and scientific profession, EMI Recording Studios (later to be renamed Abbey Road), employed engineers who had served in World War II and wore white lab coats over their jackets and ties. They were expected to follow tradition and technical guidelines that were often issued long before modern equipment was invented. It was into this environment that a 15-year-old Geoff Emerick found himself when he was working as an apprentice assistant and got to hear the Beatles first record, “Love Me Do,” with producer George Martin. Little did anyone in that room realize that in just four short years, Emerick would be sitting behind the console at EMI’s Studio Two and fabricating recording techniques to go toe-to-toe with the increasingly innovative musical and sonic concepts of the Fab Four. It would result in a series of landmark albums: Revolver, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Magical Mystery Tour, The Beatles, and Abbey Road.

Geoff Emerick and Howard Massey’s book, Here There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of the Beatles chronicles his combination of creative sound engineering brilliance, a defiantly brave streak with a willingness to break EMI’s archaic rules if it meant achieving the aural colors demanded by the Beatles at their zenith, and a good helping of youthful naivete. Emerick recounts his promotion to become the Beatles’ engineer for Revolver, notes how events cascaded from 1966 to the Beatles’ breakup in 1970, and discusses his work on some of their various solo projects afterwards. His book debunks many myths about the Fab Four, and explains in detail how necessity became the mother of invention for recording many beloved Beatles songs in the days before there were unlimited track counts, Auto-Tune, and other digital enhancements.

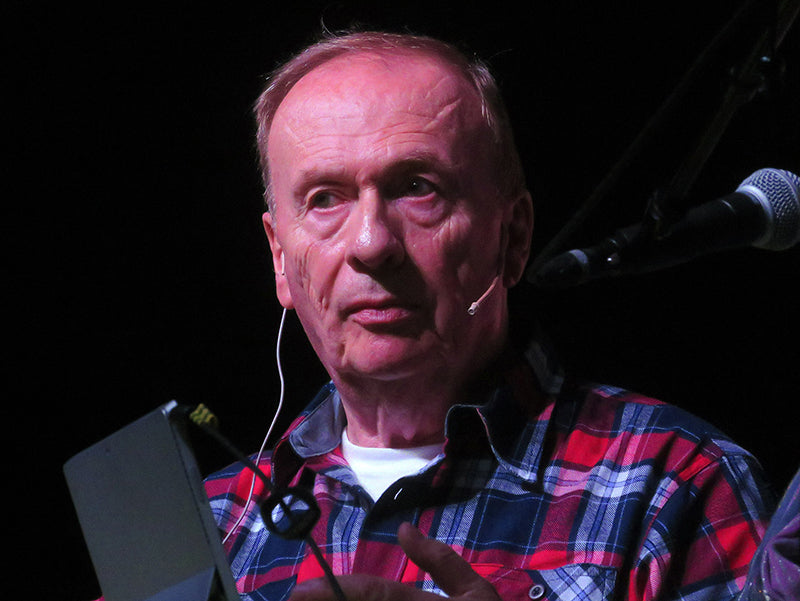

Geoff Emerick. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Eddie Janssens.

With the benefit of hindsight, Emerick also explains the rationale behind many seemingly random and serendipitous events throughout his career. For example, he recalled that George Martin’s role as the Beatles’ producer was primarily within the scope of musical performance and in finding and using other musicians (including himself) to provide what the Beatles could not play on their own, such as the use of orchestral instruments and classical stylings (including the “harpsichord” on “In My Life,” actually a sped-up piano). Martin would also judge whether the takes of a song had any “clams” that rendered them unusable. Apparently Martin, known primarily for comedy records before producing the Beatles, relied on EMI engineer Norman Smith (himself a pop musician) in the early days to translate the Beatles’ musical ideas onto tape in a manner that could replicate the Chuck Berry, Everly Brothers, Motown and Elvis Presley records that they adored.

(Note: Emerick’s criticisms about Martin and the musicianship of George Harrison created some controversy among Beatles fans and historians. Ken Scott, who worked as Emerick’s assistant at EMI and went on to work with David Bowie and others, would rebut some of Emerick’s observations in his own book.)

With the rest of EMI Studios’ engineering staff still mired in classical and early jazz music, and as unfamiliar with rock and roll as Martin himself at the time, Smith’s departure in 1966 to become a freelance producer left Martin with little choice other than to promote the 19-year-old Emerick to the engineering chair for the Beatles, primarily due to his prior relationship with the group, which had been seasoned by working on some sessions assisting Smith.

Having already experimented with sitar (“Norwegian Wood”), fuzz bass (“Think For Yourself”) and feedback (“I Feel Fine”), the Beatles wanted to take their sonic ideas to new, esoteric levels, and Emerick rose to the challenge with innovations that revolutionized music engineering at the time and have now become industry-standard techniques.

Emerick’s baptism of fire commenced with Revolver, and his first song was John Lennon’s “Tomorrow Never Knows.” Unlike any other previous Beatles song, “Tomorrow Never Knows” is a single-chord song with drones, otherworldly sounds and influences ranging from LSD to The Tibetan Book of the Dead, all of which reflected the counterculture of the 1960s and other elements. With sonic requests from the Beatles that included Lennon wanting his voice to sound like “the Dalai Lama singing from a mountaintop,” and that “none of the instruments should sound like themselves,” Emerick took close-miking and audio compression to new, unexplored levels. These recording techniques broke every rule in the EMI manual and would have gotten Emerick fired had it not all been done for the Beatles.

Ringo Starr was ecstatic over the huge sound Emerick achieved on his drums. The new approaches towards the recording of the sitar and tambura, and the flying in of tape loops were also groundbreaking EMI firsts. Emerick capped off his first-day on-the-job triumph with the notion of patching John Lennon’s vocal into a Leslie rotating speaker to capture a “whirling” sound. It was out-of-the-box thinking that pleased Lennon to no end, and which cemented Emerick’s future with the Beatles and Martin.

Geoff Emerick and Paul McCartney developed a simpatico working relationship during the making of Revolver that continued throughout their respective careers. Emerick attributed much of it to a shared work ethic, as McCartney was the most concerned with achieving musical professionalism in the studio, and could become impatient with his fellow Beatles. Lennon’s drug use and short attention span, and Harrison’s slow and deliberate approach towards lead guitar parts would sometimes grate on McCartney, who appreciated the willingness of Starr and Emerick to do as many takes as needed.

The inability of the Beatles to recreate many of these new sounds in concert, combined with the pressures of Beatlemania and the primitive PA systems of the day (which lacked monitor speakers for the musicians and could not be heard over the screams of adoring fans), prompted the Beatles to abandon live concert performance and focus solely on recording, another turn of events that was destined in the cards for Emerick.

Contrary to the hype about an album as complex as Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band being recorded only on a 4-track tape machine, while that is true, Emerick discloses that a second 4-track machine was slaved via a sync tone, which allowed for 6 tracks to actually be used. However, the massive undertakings of orchestral arrangements, premixing and bouncing tracks in advance of doing the final mix, and overdubbing of McCartney’s bass instead of recording it live with the band (as had been done previously) created numerous sonic obstacles never before encountered. Even the syncing of machines was done manually until the sync tones kicked in and locked, so a good deal of guesswork and painstaking re-tries were required.

All that said, the sonic results still stand today as an incredible musical and technical achievement, and Sgt. Pepper’s earned Emerick his first Grammy Award win. He had to fight with Abbey Road’s management to be able to take the trophy home afterward.

Emerick notes that to truly appreciate Sgt. Pepper as it was originally intended to be enjoyed, the mono mix is the one that he and the Beatles preferred, in spite of the digital stereo mixes that have followed in later decades. The extra clarity in the newer mixes brought up sounds that were intentionally supposed to be obscured and subconsciously heard instead of noticed overtly.

Emerick witnessed the fracturing of the Beatles, beginning during the recording of Magical Mystery Tour and continuing through The Beatles (aka the White Album). He saw Yoko Ono’s influence pushing Lennon in a more avant-garde direction, as well as Lennon’s heroin addiction causing further estrangement from the rest of the band. The death of manager Brian Epstein in 1967, Harrison’s growing infatuation with Indian music and frustration over his songs getting less attention than those of Lennon and McCartney, and the Beatles’ increased confidence in the studio (ironically due to Emerick’s role in realizing their sonic ambitions) all contributed to reduce George Martin’s influence as the Beatles’ producer. These factors and others all snowballed towards the Beatles’ final break-up.

Emerick describes how Lennon’s constant verbal abuse over his guitar sound for “Revolution,” even after he had delivered yet another iconic sound through unusual means, drove Emerick to quit before the album was finished.

The Let It Be sessions, produced by Phil Spector, are described as disastrous, since Spector’s egomaniacal ways were not tolerated by the British orchestral musicians. To Emerick’s horror, Spector had erased some of McCartney’s vocals on “The Long and Winding Road” in order to fill more tracks with the poorly-regarded string sections. Unwilling to work with the mercurial Spector, leery of his fetish for guns and intimidated by his large bodyguards, Emerick quit his job at Abbey Road, leaving assistant engineer Glyn Johns to finish the recording of the Let It Be album (and to record the rooftop concert that formed the basis for The Beatles: Get Back documentary and yielded three tracks for Let It Be).

Although Lennon and Harrison got along well enough with Spector to work again with him on some of their subsequent solo projects, the Beatles requested Geoff Emerick and George Martin to come back for the recording of Abbey Road, which earned Emerick his second Grammy Award. Abbey Road Studios had finally installed an 8-track recorder and other newer equipment, much of it of solid-state rather than the older vacuum-tube equipment. Emerick thought that the new gear lacked the punch of the more familiar tube-powered Fairchild compressors and EMI console, but the softer sound luckily complemented the new songs, especially Harrison’s standout ballads “Something” and “Here Comes the Sun.”

Geoff Emerick’s personal insights into the culture of Abbey Road Studios and its internecine politics during the 1960s offer a fascinating look as to just how iconoclastic the Beatles were in upsetting the order of the day in the UK – and how ludicrous some of it seems in retrospect some 50-plus years later. Apparently, Abbey Road felt that the fact that the Beatles were signed to the EMI record label would ensure their loyalty, so Abbey Road Studios took the Beatles’ continuing relationship with them for granted.

Some examples of this include:

- The refusal of management to acquire an 8-track recorder when independent studios like Olympic Studios (where the Beatles recorded “All You Need Is Love” and “Baby You’re a Rich Man”) and Trident Studios (where “Hey Jude” was recorded) had already been using them successfully for other artists. Abbey Road Studios’ first 8-track deck arrived just in time to record the Beatles’ swan song record, ironically titled Abbey Road.

- Despite the boatloads of money the Beatles generated for EMI, Abbey Road management had little to no regard for the sonic innovations created by Emerick. Taking a condescending attitude towards engineers in general by thinking them as interchangeable, Emerick would be randomly taken off Beatles sessions by studio management and replaced by engineers who may have done big band jazz or classical music but had no idea how to mic electric guitars or execute the ADT (automatic double tracking) and other techniques emblematic of the Beatles’ records. One manager in particular would refuse to keep the studios open during the Beatles’ late-night sessions, when they were often at their most productive creatively. The Beatles’s frustration from this lack of respect prompted their ill-fated experiment in hiring Yannis Alexis Mardas, known as “Magic Alex,” as head of Apple Electronics. He had implemented a number of strange ideas to build a new studio that had to be scrapped, and Emerick was then brought in to design Apple’s recording studio.

- As rock music was still held in disdain by Abbey Road’s older management and staff, they had no qualms about swapping the Beatles out of their usual Studio Two, which had an ideal sound for rock music, into the cavernous Studio One, which was designed for orchestras. This led to Emerick having to improvise baffles and sound absorption materials from whatever was available to make the room usable for Beatles sessions. That said, some of the reverberation “mismatches” on several Beatles songs are now revered as part of the songs’ unique sounds.

When the Beatles formed Apple, untold thousands of dollars were pilfered by Magic Alex, who had convinced the Beatles that he was an electronics wizard. After businessman Allen Klein was brought in to clean up Apple’s finances, he realized that Apple’s recording studio was one of the only parts of the company which Klein realized could be viable, but Magic Alex had to be dismissed and real engineers were needed. Emerick got the nod, since he had already been engineering for Ringo Starr’s solo record, Sentimental Journey. He had also done work for Apple artists including Jackie Lomax, Mary Hopkin (who’d had a hit single with “Those Were the Days,”) and Badfinger, who Emerick wound up producing as well.

Ironically, Emerick’s professionalism resulted in Apple Studios becoming a lucrative independent enterprise on its own, as its recording facilities and disc-cutting operations became so in-demand that even the Beatles found it difficult to book studio time for their own solo projects there in later years. George Harrison did manage to get parts of Dark Horse and Living in the Material World recorded at Apple before it finally closed in 1975, and Emerick rejoined George Martin at the latter’s AIR Studios in London.

Geoff Emerick’s relationship with McCartney remained the strongest post-Beatles, and he engineered McCartney’s Band On the Run (which garnered Emerick his third Grammy Award), London Town, Tug of War, and Flaming Pie. During his tenure at EMI, Emerick was responsible for engineering other hits, such as the Zombies’ “Time of the Season.” Before his passing in 2018, Geoff Emerick produced or engineered a host of other artists including Elvis Costello (All This Useless Beauty, Imperial Bedroom), Robin Trower (Bridge of Sighs), Jeff Beck, Supertramp, Nellie McKay, America, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Fanny, Ultravox, Echo and the Bunnymen, Cheap Trick, Kate Bush, and many others.

Postscript – Editor’s Note from Frank Doris: I had the privilege of meeting Geoff Emerick at the 2017 Audio Engineering Society convention. He was in the Audio-Technica booth saying hello to a few people. He noticed that I had noticed his badge and done a double-take, and smiled back at me. He seemed friendly and approachable, so I went up to him and just said, “thanks for the music.” He smiled more, then looked at me as if he was expecting me to ask the inevitable.

I said, “you must be sick of people asking you about the Beatles, so I won’t do that. He replied, “oh no, ask me anything you want!” At which point, those around him started asking him questions about what it was like to work with the Beatles. He answered them graciously. Among other things, he told us (I’m paraphrasing a little), “a lot of what you’ve read about the Beatles is completely wrong.” Also, “some of their greatest moments were the result of mistakes, where they decided to go with the ‘mistake’ and got something completely amazing out of it.”

0 comments