Author’s note: The following article was written in spring 2021 for the recently-published book Record Store Day: The Most Improbable Comeback of the 21st Century (Rare Bird Books, Los Angeles), but along with other material was edited from the book. We present it here exclusively for Copper.

A recurring theme while researching Record Store Day was the need for more pressing capacity to keep up with the consumer demand for vinyl. So far, the backlog hasn’t prevented Record Store Day (RSD) titles from being manufactured. (See the 2022 update at the end of this article.)

While RSD is responsible for only two production cycles during each year, the hope is that every day is Record Store Day, so that fans get used to regularly visiting their favorite stores, or their online destinations (because of COVID-19 concerns) if they’re unable to shop in person.

Besides the pandemic forcing everyone to change how they do business, other factors have threatened to disrupt the vinyl supply chain. Rainbo Records, thought to be the second-biggest US producer of records in recent years, closed in January 2020 after 80 years of being in business, due to the landlord no longer wanting a manufacturing firm in the building. The high cost of doing business in California made it prohibitively expensive to move the factory elsewhere in the state, concluded owner Steve Sheldon, whose old office was used as a set for actor Paul Giamatti in the movie Straight Outta Compton about the rap group N.W.A. Rainbo sold its pressing equipment to United Record Pressing (URP, the largest pressing plant in the US), and completed its last job in December 2019, closing out six million units produced in the facility that year. Seven days after Sheldon closed the doors for good, another development threatened vinyl production.

In February 2020, a fire destroyed Apollo Masters in Branning, CA, the world’s biggest supplier of lacquers, the blanks needed to make the acetates used to make record pressing molds. Apollo was also a major manufacturer of the styli needed for cutting the lacquers.

The acetates for the 2020 Record Store Day titles were already produced by the time of the Apollo fire. The finished records were ready and waiting to be shipped to brick-and-mortar retail in time for RSD 2020 in April, which had to be pushed back to three drops in August, September and October 2020 due to the pandemic.

As vinyl came back in vogue and the major labels jumped on the bandwagon, as did the big-box retailers, some indie labels were concerned about being able to reserve pressing capacity that might be compromised by large-volume siphoning.

A record pressing machine that was purchased by United Record Pressing. Courtesy of Rainbo Records/Steve Sheldon.

In fact, Fat Possum Records became a partner in Memphis Record Pressing, which opened in 2014 and now produces vinyl for indie labels as well as for Sony. Before the vinyl resurgence of the past 15 years, all three major labels owned manufacturing facilities, remnants from vinyl’s original heyday. Over in Hayes, England, EMI operated a pressing plant that is now independently owned and known as The Vinyl Factory. Record Industry in The Netherlands used to be owned by Sony.

In 2005 in the US, Universal shut down a vinyl pressing plant in Gloversville, New York, “even though by all accounts the factory was making money,” wrote Michael Fremer in Analog Planet. “These days, it’s all about the short-term corporate bottom line. Shut it down, sell the assets, take the payroll off the balance sheet, and guess what? Better short-term bottom-line!” The Universal plant, which opened in 1964, had 112 employees and sold its lines to URP. Universal spokesman Peter LoFrumento then offered a PR-speak statement: “While decisions like these are difficult to make and are not undertaken lightly, they are necessary to meet the many new challenges brought about as the industry continues to rapidly evolve.”

Bringing the current vinyl manufacturing crunch into perspective, Sony Music International’s Gerhard Blum observed: “The reality in today’s world is [Sony] and no one in the industry can get enough vinyl right now. [The comeback] is beyond your wildest dreams. And there are some factories that now have a lead time of up to nine months.”

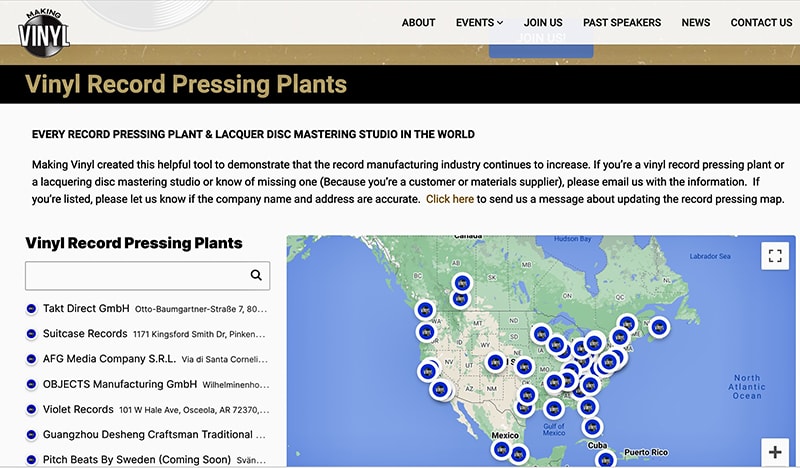

A map of US and Canadian record-pressing plants. Courtesy of Making Vinyl.com.

The Netherlands’ Record Industry Vowed to Press “The Last LP”

For more than 20 years, Anouk Rijnders has worked at Record Industry in Haarlem, Holland, currently as project manager of the company’s mastering facility Artone Studio. “Record Store Day certainly helped enormously in making the customer more aware of vinyl record stores,” says Rijnders, who joined the company as a recent college grad two years after Ton and Mieke Vermeulen bought the plant from Sony Music in 1998 when the plant produced 1.5 million LPs that year.

The next year, Record Industry’s output more than doubled to 3,741,842 LPs, and additional impressive growth occurred in 2000 with 4,662,427 LPs and 7,749,272 LPs produced in 2001. At the time, the facility was somewhat busy because other major pressing operations had gone out of business. But then, for two consecutive years production was off by more than 1.9 million LPs.

In college, Rijnders studied filmmaking and television, and found a first job in the field. Yet she was drawn to manufacturing records when the opportunity arose. “We always believed in the future for vinyl and that is because it’s a product with emotion,” Rijnders said, adding that most people consume music via Spotify, or in the past, on an MP3 player. “You don’t even know what the cover looks like or who wrote it or even who sings it, because it’s an anonymous file. There are still more than enough people who are not happy with that; they want something you can touch, feel, smell, experience. So there will always be a market for that.”

A few years into working there, Record Industry’s busy times subsided.

“I told Ton and Mieke, ‘If you have to let me go, please do so’ because perhaps 15 years ago we had to let go of quite a number of people. I had no family yet. It would have been much easier for me to find a new job than people [who] needed to support their families. But, Ton always said, ‘The last record in the world will be pressed at Record Industry.’ Even Ton did not imagine it [vinyl demand] would go up and up and up again. I remember a newspaper in The Netherlands said that ‘Vinyl comes back more often than Jesus stood up,’ something like that, because it’s still surprising for everyone.”

Record Industry hit a high of 10,309,834 LPs manufactured in 2017, and it’s since leveled off a bit with 9,248,000 in 2020, a year when it was expecting only steady growth. Then the pandemic hit, and, “it’s been incredible.” To meet the demand, in late 2020 the company hired about 30 people, mostly musicians – drummers, guitar players, sound technicians – “because of the busy season.”

Record Industry is a partner in the Music On Vinyl reissue label, always active for Record Store Day. In fact, since 2008, Music On Vinyl has released more than 3,000 titles, including new three-LP artist compilations under their “Collected Series,” for which it licenses tracks. “Each year, [Music On Vinyl] does its best to put out special releases and get out rare stuff, including soundtracks,” Rijnders said. By being part-owned by Record Industry, Music On Vinyl most likely doesn’t have the backlog issues that Sony Music International ironically is now facing.

Beggars Considers Getting Into Pressing (Again)

The Rough Trade record shop in London’s Ladbroke Grove opened in 1976, and soon gave way to the Beggars Group of labels. Beggars in recent years intermittently considered opening its own pressing plant as a way to resolve the backlog of getting its records made. “We’re currently back in the conversation about this based on the backup at the final manufacturing plants right now,” explained former US group label head Matt Harmon. “We have over 200 orders that we can’t fill. We have a lot of back catalog that we’re trying to sort of manufacture at this point.”

Beggars considered getting into vinyl production about four years ago when orders were backed up by 100,000 units. “We have been talking about how we sort of deal with this,” Harmon said. “One of the ideas would be to open a record pressing plant. We’ve debated it internally for the last five years or so. It’s about capacity. If we’re getting guaranteed capacity at some of these plants, that is great. But if you’re getting 20,000 or 25,000 LPs a month, you have a number of double LPs, so when you remanufacture, for example, Radiohead’s catalog, you’re talking about a number of double LPs. It’s been fantastic that the smaller plants have opened up, but it’s very hard to use them to do the level of repress that we tend to sort of need.”

Not for the faint-hearted, building a new pressing plant from scratch is quite an undertaking from both a financial (i.e., investment of millions of dollars) and technology standpoint, despite Canadian vendor Viryl offering its WarmTone fast-turnaround pressing solution, along with Swiss hardware supplier Pheenix Alpha also cranking out new machinery. It’s not your father’s record industry to be sure. Everyone along the vinyl value chain is working smarter and leaner, perhaps with greater cooperation than what existed in the past. That camaraderie is especially evident in the birth of new pressing plants over the past few years.

“[Running a pressing plant] is the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life,” Sean Rutkowski, then general manager of Independent Record Pressing in Bordentown, New Jersey, told a Making Vinyl conference in 2018. Asked what he learned along the way, he replied, “Double your projected costs and cut the revenue in half.” Co-panelist Jeff Truhn, operations manager of Cascade Record Pressing in Milwaukie, Oregon., noted that labor will cost more than expected.

Another record pressing machine at United Record Pressing. Courtesy of Rainbo Records/Steve Sheldon.

Occasionally, half-century-old pressing equipment will show up on eBay for sale, prompting bidding wars. Third Man Pressing and Furnace Record Pressing pursued the same seller in Mexico, with Furnace winning out.

Furnace principal Eric Astor, who spoke at the first Making Vinyl conference in November 2017, had been involved in pressing seven-inch singles of friends’ bands since he was a teenager in Arizona. He started participating in Record Store Day in 2009, overseeing the manufacturing of a couple of titles and in 2010 became an RSD sponsor. “At the time, I don’t think there was a manufacturer that had been involved, so it gave us some good exposure.”

Eventually Furnace also made CDs, but Astor also worked as a broker for the large German pressing plant Pallas Group. “Frankly, we were getting so much work that the shared capacity that they’re giving to us as a broker wasn’t enough. So we bought our own machines to guarantee the additional capacity that we needed to keep up with the demand. By 2018, Astor was ready to open his own plant in Alexandria, Virginia.

“Every year in the months leading up to Record Store Day we see a rush of new orders, not just from official RSD titles, but from general volume riding the anticipation of the event,” points out Paul Miller, vice president of sales at Precision Record Pressing, outside of Toronto, Canada. He could be talking for all pressing plants. “This [demand] has become something we can count on and that’s had a really positive impact on our business.”

Generally speaking, record labels that take advantage of RSD are already placing orders with Precision throughout the year. Labels with rich back catalogs view RSD as the perfect time to reissue from their catalogs with a deluxe treatment to reintroduce the title to the public.

“These reissues get more people out to stores, and while they’re there and in a vinyl buying mood, many will take a chance on titles by lesser-known bands too,” Miller says. “The net effect is that more people buy vinyl on Record Store Day whether it’s an official title or not, which plays a part in encouraging new record labels to get involved in making vinyl too.”

Six years into owning and operating its own plant has been a learning experience for Third Man Pressing. “From late December through March, that’s the crazy season for vinyl records,” says Ben Blackwell. “But now, vinyl records are just 12 months of crazy season. It’s not really dying down. The more we get our capacity dialed in, the more it overwhelms and becomes tricky,” he added.

The first Record Store Day launched as Cleveland-based pressing plant Gotta Groove Records was forming. “The excitement it created at that time was something that I had not previously seen in the market, and I knew RSD was going to be a success,” says Gotta Groove President Matt Earley, adding that it was the “official pressing plant sponsor” for RSD in 2009 when “even my most curmudgeonly stores were onboard.”

Some of Gotta Groove’s earliest customers are still with the pressing plant, and among those who have had their RSD pressed there are Colemine Records, MVD, and Thirty Tigers.

Meanwhile, Steve Sheldon is in retirement mode in southern California. When Sheldon joined Rainbo in 1971, all they made was vinyl, later expanding into manufacturing cassettes, CDs and DVDs. “I have a special place in my heart for the vinyl. I miss it a little bit. But I don’t miss the aggravations that go along with it. At one time, I had 140 employees. A couple times a week, I’d wake up at one or two in the morning, walk the floors and never fall back to sleep. And that was not unusual. I’ve never slept better. I sleep eight hours through the night. If I happen to wake up, I fall right back to sleep.”

******

2022 Update:

Some RSD titles that were planned for April 23, 2022 were pushed to a newly-created June drop because of supply chain issues, not so much because of a pressing backlog. Previously, and initially conceived as a COVID-19-safety precaution, three RSD drops happened in August, September and October 2020, and then in June and July 2021, in addition to the previously planned Black Fridays for both years.

In March 2022, Jack White made an appeal that went viral, calling for the major labels to build their own pressing plants once again to meet consumer demand and loosen the 10-month backlogs, which have also impacted his own Third Man Pressing facility in Detroit. I knew from my own research, as mentioned above, that Universal, Sony and Warner were unlikely to do so.

At the 2022 Making Vinyl conference in Nashville, Third Man Records’ Blackwell admitted that White didn’t really expect the majors to really get back into the pressing business, acknowledging that they were perfectly happy outsourcing their needs. When I interviewed Blackwell for the book in January 2021, I asked him what the chances were that Third Man might also open a plant in Nashville, where the label is headquartered. He drolly responded, “Nashville already has a plant,” meaning the aforementioned URP, which helped Third Man Records create a liquid-filled record in 2012, and the “fastest record” stunt on RSD in April 2014, in which White recorded two tracks before a live audience and had 900 copies of a URP-pressed seven-inch single for sale within four hours.

Attendance was high at the 2022 Making Vinyl conference. Courtesy of Making Vinyl.com.

Unbeknownst to both Ben and me, a flurry of announcements in April 2022 would promise new pressing capacity from existing and new players, including URP, which is doubling capacity at its Nashville facility.

My Making Vinyl co-founder Bryan Ekus and I looked like geniuses for staging our first post-pandemic event in Nashville at the boutique facility The Vinyl Lab, where attendees could watch records being pressed while listening to the conference. But then we learned that long-time mastering engineer Piper Payne was also opening her own nearby plant, Physical Music Products, and that GZ Media – the world’s largest record factory, in the Czech Republic – was building Nashville Record Pressing, which will deliver a maximum capacity exceeding 20 million records per year by the fall of 2023.

Brandon Seavers (Memphis Record Pressing), Piper Payne (Infrasonic Mastering, Physical Music Products) and Ben Blackwell (Third Man Records) at the 2022 Nashville Making Vinyl conference. Courtesy of Making Vinyl.

But that’s not where the story ends.

At the 2022 Making Vinyl conference, Memphis Record Pressing, also backed partly by GZ, announced expansion plans. Then the record-membership club Vinyl Me, Please revealed it was building an audiophile state-of-the-art facility in Denver, Colorado, to accommodate its own growing record-pressing needs.

New pressing-capacity announcements didn’t stop there. Large CD replicator ADS Group COO Connie Comeau revealed plans for pressing records from its brand new facility – the first modern-era plant in Minnesota – by September 2022. Embattled audiophile label Mobile Fidelity also announced plans to open its own dedicated audiophile-record pressing plant.

Back across the Atlantic, at Making Vinyl Europe in Offenbach, Germany, Dutch manufacturing giant Record Industry CEO Ton Vermeulen announced that his company was adding 14 new presses, expanding its capacity from 11 million to 15 million records a year. And Sonopress CEO Sven Deutschmann announced the Bertelsmann-owned media manufacturer was getting back into vinyl for the first time in 30 years.

Jack White can rest easy; help is on its way.

Record Store Day: The Most Improbable Comeback of the 21st Century is available at good book stores everywhere and Amazon.com. More information about it is available at https://larryjaffee.com.

Header image courtesy of of Rainbo Records/Steve Sheldon.

0 comments