We flew into Texas knowing we were in for a tough time of it. We were looking at a no-frills bus and truck tour. It was going to be hectic, and we would travel over five thousand miles. We had thirty gigs in 35 days. There were some overnight bus rides. The routing was terrible. They had us zigzagging across the state of Texas and when we flew home all of us were exhausted. Let me back up here. It was in the early 1970s. Bruce Sachs and I got involved when Mike Martineau (the booking agent for the Peace Parade musical) called Bruce with the idea of doing a show based on the successful album Jesus Christ Superstar. We were in a unique position to implement this opportunity and were still buoyed by our recent success with Peace Parade (see my article in Issues 117 and 118). We decided to take a closer look at it. Firstly, we had cost considerations, which were paramount. We needed to have the ability to do a show every night, with the only restriction being travel issues. Keeping things simple – we knew how to do that. Salaries, while being pretty good for everyone, wouldn’t be much of a drain till we were on the road, but by then we would have cash flow. One of the things that helped us create Superstar as a road show on the cheap was that we decided to do the show as an oratorio, rather than as a full-blown production with elaborate scenery and costumes. We also had a world-class cast, with many of our performers being Broadway veterans. Most of them had served long stints in the Broadway cast of Hair. We called the show Superstar, The Original Touring Company (OATC). After a brief and successful start, some developments and realities made us have to temporarily pull the show off the road. This brought into our circle Bruce’s employer, Betty Sperber. A grizzled older gal with questionable ethics, a true music biz character. On the plus side, she had more experience than both of us combined.

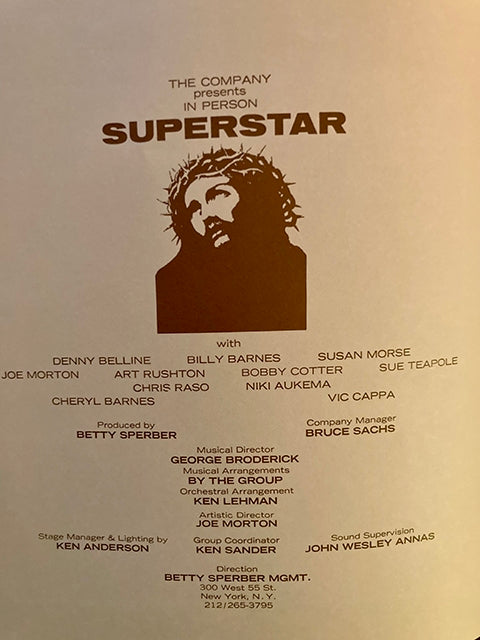

Cast of Superstar, the Original Touring Company.

Cast of Superstar, the Original Touring Company.

Fresnel fixed hanging light with barn doors.

Fresnel fixed hanging light with barn doors.The lights had to be arranged in very exact placements, which increased the drama of the performance. With the combination of 65 to 90 hanging lights and three high-intensity carbon arc follow spotlights, Kenny developed an intricate lighting script that had over 167 cues over the course of the show. It was amazing, and added such depth and expression that it propelled the show to another level. This was it, the missing element.

An incandescent followspot. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/KeepOnTruckin.

An incandescent followspot. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/KeepOnTruckin.

The beauty of all this was that it cost us nothing. We could put all of it in our contract rider that required the promoters to provide this equipment. It was considered normal and appropriate for a promoter to provide sound and lights, and we asked for nothing special. The equipment requested on the rider was readily available in most theaters, and if not, could easily be rented locally. The lights were not particularly exotic in themselves. The lighting requirements for Superstar were solidified – and it was just one more reason why the show needed an advance man. I was the obvious choice for the job. I had to make sure that the rider requirements were provided for. There were also other necessities that could be problematic if they were not in place for the show. To name a few, a Hammond B3 organ with two Leslie speakers. An upright piano, freshly tuned on the day of the show. Making sure the specifications for the sound system and the size of the stage were correct. Previously, before I did the advance work, the local promoters were frequently haphazard in fulfilling the rider. When we would pull up on the day of the show, it was too late to make substitutions, and afforded almost no time to make any corrections. It was a source of frustration for all involved when our requirements were not met, a real bummer that hurt morale. The addition of Kenny’s lights made the job of advance man an absolute necessity, where previously it was only an aspiration. I would call and book an appointment with the promoter to meet at the venue a day or two before the show, and review every item of the contract rider. That forced them to make any necessary corrections, which they did. The word got out and the promoters took our requirements much more seriously. In the rare case that there was an issue, I was able to relay that information back to Bruce, and he could advise our people of any needed substitutions or workarounds. It really worked well, and I was able to smooth out the rough spots. That made life on the road easier for everyone and our touring life was much improved. When we finally resumed touring after our hiatus, the lighting gave us the added dimension the performance needed. Our production of Superstar received rave reviews.

After a few months, the Texas block of dates came up. While we were touring in Texas, Kenny had a family emergency and would have to go home for five days. Somebody had to take over the lights. By default, that was me. I usually was a day ahead of the show and busy doing the advance work, but I was also the obvious choice for the job. My initial reaction was reluctance, because I knew nothing about lighting. The task seemed insurmountable. However, Bruce insisted that I do it. Finally, we agreed that there was no guarantee of success. I would do as best as I could, and we would hope for the best. With that understanding in place I felt less pressured. Before Kenny left, I joined him on stage for the pre-show setup and watched him direct the lighting crew, observing where the fixed lights were hung and grouped. Then the stage crew adjusted the barn doors, to be pointed at specific spots on the stage. Kenny drew up a diagram of how each light was pointed and grouped, and which colored gels would be used. During shows, Kenny and the lighting crew communicated with each other via headsets. The night before the show I would be in charge of, I listened in on a headset to Kenny and the three follow-spot operators, along with the operator of the lighting mixing board. Following along with the notes on the script, I saw and heard how he called the show, and that gave me a good idea of how it was done.

Next morning Kenny flew home, and we were off to Lubbock for two nights in a dirt-floored arena. It was big and smelled rodeo-ish. I felt that I could do it, well, at least sort of, and I was up for it. My first afternoon as lighting director, the local stage crew lowered the trusses for the lighting rigs, and the fixed lights were hung as Kenny’s notes described.. Going over the diagram with the lighting crew, they set up the banks of lights and aimed them. In a couple of hours all the fixed lighting was hung, gelled and pointed, with their barn doors adjusted. Then the trussed were raised back to the correct height, and only slight adjustments had to be made. Here and there, crew members climbed ladders, made the final adjustments, and locked everything down. That evening about a half hour before the show, I took my place in the balcony next to one of the follow-spot operators, and we put on our headsets. Me, the three follow-spot operators, and the lighting board tech were all situated on the main floor, with the lighting board placed next to the sound booth. While getting familiar with the operators, I asked them how often the lighting elements had to be replaced. The high-intensity carbon had to be replaced every 30 to 45 minutes of use, and took about one minute or so to replace. They would notify me in advance so that I could find a break in the script and give them time to do the replacement. We prepared for the show to start. And away we went. I started calling the lights. This was turning out to be fun, and my operators were very professional. I gave alerts, and made the cues and lighting calls. It was going better than I had expected. The show ended and I thanked my guys. They told me it was fun, and enjoyed working with me. They were unaware that this was my first time. By my account I made just a couple of mistakes, but they were brief and quickly corrected.

Advertisements for Superstar.

Advertisements for Superstar.

I went backstage to the dressing room with a big sh*t-eating grin on my face. I was very pleased with myself. I saw Bruce, Susan (Morse, my girlfriend, who played Mary Magdalene), and everyone else in the dressing room just going about their business. I must admit I was surprised. It was inexplicable that no one paid any attention to me. No acknowledgement. nothing, nada. Well, what was I expecting, applause? Yeah, something like that, but seemingly they were not particularly interested. At that moment, I was speechless, and it began to dawn on me that nobody cared. Unless you make some horrid mistake, it seems like nobody notices. Apparently the only one who thought this lack of acknowledgement was a big deal was me. I quickly wiped the smile off my face and tried to appear nonchalant. Thinking about it later in bed that night, I realized that this is probably how a sound mixer feels. No one says anything to them except: “It was too loud!” “I couldn’t hear the monitors!” Or, some other kind of complaint. Silence is good news, because you are not going to get a compliment for a job well done; well, rarely maybe if ever. Kenny came back a day early and he also hardly said boo to me. No big deal. My lighting career was complete, finito, over. A brief but a hell of a good experience. Kenny Anderson later worked for Aucoin Management and became KISS’s production manager from 1976 – 1982.

Header image courtesy of Pixabay.com/KlausHausmann.

0 comments