High Crimes and Misdemeanors

Nobody ever accused the record labels of unnecessary largesse. While the audiophile companies like Impex, Analogue Productions, Mobile Fidelity, Speakers Corner, Intervention and others show care and diligence above and beyond the call, by thinking and acting just like the collectors, music lovers, and audiophiles they serve, the majors have the morality of fast-food chains. Just compare the quality of any audiophile label’s LP sleeves with those of any mass-market releases if you don’t believe me, let alone the grade of the inner sleeves.

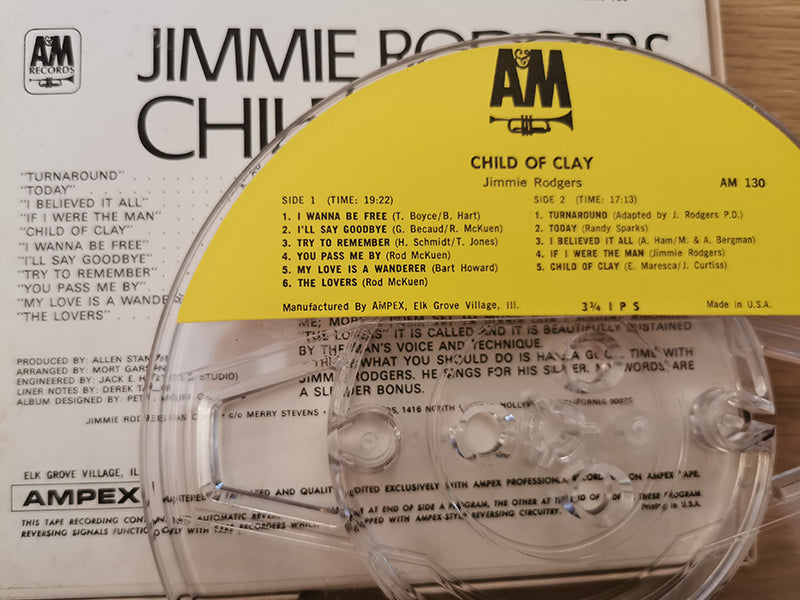

It’s all about the bucks and cutting corners and generally taking the cheapest route – and it was true even for premium products like pre-recorded reel-to-reel tapes way back when. As a reminder, I have in front of me a 1/4-track tape – not even the premium 1/2-track edition of the same title – and the manufacturer’s printed-on-the-box price in 1960 was $9.95. That’s $96 in 2022 dollars. And we earn a lot more than they did in 1960.

Make no mistake: aside from promotional samplers, such as the Realistic-branded tapes for RadioShack stores selling for $3.95, pre-recorded open-reel tapes always cost more than the equivalent LPs. When open-reel tapes first appeared, though, they were as luxurious and high-end as today’s 180-gram or 200-gram 45 rpm limited-edition, boxed LPs.

This inexorable decline in the quality of commercial tapes is yet another of the historic rediscoveries I’ve made by turning my clock back to what was the original audiophile era. All you have to do to repeat my learning experience is to acquire a few tapes by a single favorite artist or tapes from a single label, over as short as a 10-year span, to see how the record companies made everything cheaper. Think of any singer or conductor who had a long contract, and who issued a steady flow of titles. You will be shocked by the degradation.

Just as hard-hitting an illustration of this downgrading comes through comparing an early tape to its later release; for example, any best-selling soundtracks or classical albums which stayed in the catalogue for years. I have six different copies of one favorite (which I will not name as I was not put on this planet to subsidize lawyers) spanning 15 years, and you don’t need any set of particular forensic skills to detect how everything from the tape stock to the quality of the box to the tape speed was downgraded.

Only rarely, as in the case of the Beatles, did the packaging or the tape quality go up, as when Capitol Records realized that the Fab Four was the biggest musical act ever. The label stopped releasing the Beatles’ albums as economy-minded 3-3/4 ips 2-on-1 tapes and reissued them at 7-1/2 ips. Better late than never, I guess, when you appreciate the cash cow that happens to be in your barnyard.

Sadly, it’s exactly like the makers of candy bars shaving off a gram or two of chocolate while the price stays the same, rather than raise the price and thus aggravate customers who see the immediate pain of inflation: it’s blatantly obvious when you see a piece of candy go from $1.49 to $1.79, but not so noticeable is a 3-ounce candy bar suddenly dropping to 2.8 oz. Only much later do you realize that the peanut butter cup is much smaller than you recall…and it ain’t nostalgia at play.

Record labels were once the leaders in recording technology, and one cannot praise enough the geniuses in the studios of Capitol, CBS, RCA, EMI, Decca or a few others. But – as seen with the BBC’s decline – commerce always trumps worth. To facilitate the decline in tape quality over its first decade, from sound quality which is still to be bettered 65 years later to something less astounding, the record labels made moves far more egregious than using cheaper boxes, nastier tape and thinner spools, which I’ll get to in a bit. Instead, they weakened the core product.

Sadly, the biggest enabler was the actual technology they were promoting to the very end as the best-sounding format of them all. Just as the deaf morons in the music biz circa 2022 try to get the masses to believe that streaming sounds as good as LPs (or CDs, cassettes or whatever other source you can name), so did the record labels a half-century ago try to convince the public that every new development in tape technology was desirable and an advancement. You cannot believe the raves they applied to moves which technically halved the quality, just as idiots still insist that anything digital is automatically superior to anything analogue.

As the blank tape and tape deck manufacturers created different tape formulations and devised new head configurations (see Part 11 in this series in Copper issue 158 for an example of early stereo conversions), the record industry swiftly moved from the first stereo configuration of 7-1/2 ips, 2-track tapes to 7-1/2 ips, 1/4-track tapes. This immediately halved the amount of tape needed for the same playing time. Ker-ching!!! Instant savings in raw tape! Unfortunately, the quality dropped, too, and I have enough early tapes issued in both formats to demonstrate to anyone who cares to sit in my listening room that the difference is audible.

(Note: Debate rages as to which compromise causes the greater degree of loss in quality: going from 1/2-track to 1/4-track, or dropping speeds from 15 ips to 7-1/2 ips to 3-3/4 ips. The consensus, according to my mentors, is that irrespective of speed, moving from 1/2-track to 1/4-track is the greater loss. As for slower speeds, it is arguable that the quality loss incurred by moving from 7-1/2 ips to 3-3/4 ips is more audible than the drop from 15 ips to 7-1/2 ips. Before you hit Send on your “F*ck you, Kessler!” e-mail, I emphasize that this is NOT a statement of fact, merely a gathering of opinions from professionals with whom I have discussed it. Obviously, a 15 ips 1/2-track tape betters the rest, but I am concerned only with pre-1980 commercial tapes. I mention these permutations only for you to gauge precisely how the record industry chose to economize.)

Next came the speed drop to 3-3/4 ips, halving the amount of tape needed once again. Hooray! sang the accountants and shareholders. Far be it for me to defend the music industry, but it is worth noting that 7-1/2 ips tapes did not disappear altogether, though it seems that the 1/2-track tapes of the format’s early days were fully supplanted by 1/4-track tapes by 1960.

As for the continued use of the higher speed, and not counting the aforementioned upgrade to the Beatles catalogue in the USA as late as 1970, certain labels and specific artists continued with 7-1/2 ips 1/4-track tapes long after the slower speed became common. Indeed, I have precious few classical tapes which were not released at 7-1/2 ips, while some artists such as Andy Williams and Herb Alpert were afforded the higher speed for most of their tape releases. (I like to think Williams and Alpert insisted on the better sound quality – closet audiophiles perhaps?)

Then came the physical cost-cutting. Box quality was an early victim of downgrading, and one can easily follow the trail from substantial, cloth-hinged boxes to thin card. The relative quality of the boxes is readily apparent due to the passage of time: 1950s Jackie Gleason titles in Capitol Records “brown boxes,” the cloth-hinged South Pacific soundtracks, early Johnny Mathis and the like versus the later releases, ad nauseam, which the years have shown suffered poor protection. Along with learning how to splice and attach leader tape, I also learned how to reinforce the box spines with clear 2-inch-wide packing tape.

Speaking of splicing, another area of record label penny-pinching was the fitting of leader tape and tail, or the failure thereof. A rough estimate from my collection of 2,500 tapes is that only one in 50 left the factory with both. How do I know that the leader and tail weren’t merely discarded or sacrificed by the early owners? Simple: I have now acquired at least a dozen sealed, NOS (new old stock) tapes, all from major labels and by name artists, and not one had leader or tail.

Spool quality, too, dropped, from thick, precision-molded plastic to some spools so thin that they warp. One tape’s spool – I date it around 1975 – was so thin that I was reminded of the worst scam ever foisted on pre-recorded music: those horrible RCA Dynaflex LPs which weren’t much thicker than freebie flexi-discs. This spool was so thin that it couldn’t be gripped by the trident spindles on any of four tape decks, the spindles with the cross-section like a Mercedes-Benz logo and a specific range of height travel, which suggests that it didn’t even adhere to industry standards. To keep it from rattling and shimmying, I had to play it on tape decks like the Denon DH-710F, with a smooth spindle and a friction grip rather than a trident spindle.

Bent out of shape: our editor demonstrates the flimsiness of a 1974 RCA Dynaflex record.

They didn’t stop there. To save on production costs, the boxes often used the exact same front and back artwork as the LP, which kinda sucked when the A- and B-sides were flipped, or – worse – the track order changed. When an album’s track order was carefully sequenced, this was an insult to the artist as well as the customer.

It has been suggested by one colleague that this might have been due to the playing times of the two sides, as the labels preferred to avoid an imbalance, where one of the sides finished earlier than the other, leading to a long silence at the end of one of the sides; most of the tapes I have seem to be within ±3 minutes from A-side to B-side. However, I have more than a few classical tapes where, in the interest of not interrupting a movement, one side is far longer than the other. Does it bother me? Not at all. But did ruining Buffalo Springfield’s Last Time Around with a messed-up track listing upset me? You bet your head demagnetizer: as a hard-core Buffalo Springboy, I ended up buying two copies because I thought the first had been reprogrammed by some putz with two tape decks. It cost me $65 to find out that the record label had done it.

Note the track listing on the box versus the track listing on the tape. Why?!

Ironically, the dearer 7-1/2 ips 1/2-track versions of tapes that were released both in that format and also as 1/4-track tapes (albeit at the same speed) contained less material. I have a number of these and the 1/2-track version often had three or four fewer songs on it, though most were identical. The labels would publish both track listings on the box, so there was no deceit and you knew which songs you were losing if you opted for 1/2-track, while the boxes and the labels on the spools would have an ink stamp or sticker to indicate that the tape was 1/4-track rather than 1/2-track.

If the above sounds like I am being anally-retentive, or that I suffer from OCD, well, that pretty much defines all audiophiles. We are anally-retentive and obsessive. So, be warned: the next time, I will terrify you with even worse horror stories…appalling treatment of tapes from the original purchasers themselves.

Header image: for KK’s money, the best of the commercial tape spools.