In the previous episode (Issue 166), we looked at the work of Flo Kaufmann of FloKaSon in Switzerland, the man who decided to preserve the Neumann disk recording legacy by keeping vintage Neumann lathes running. In Part 12 of this series (Issue 162) we had looked at Len Horowitz and his nephew, Jacob Horowitz, of the History of Recorded Sound in Los Angeles, California. Len was a Westrex employee who decided to preserve the Westrex disk recording legacy by purchasing their disk recording department in 1995, when it closed down.

As a result of the efforts of the aforementioned gentlemen, a number of Neumann and Westrex products are still in use to this day. There is also a whole other world of individuals who have been instrumental in preserving disk recording equipment and technology in a number of ways. It’s a bit of a grassroots movement, of people experimenting with ways of using disk recording equipment with relatively low resources and plenty of creativity. At this point, my dear readers, I must warn you that we will be exiting audiophile territory and entering a world where sound quality may not be a primary concern, or any concern at all! However, no discussion of disk recording at this stage could be considered complete without a mention of the individuals who never gave up on the vinyl record and kept making records with whatever means they had available, just to keep the medium alive.

It is largely through their efforts that a lot of equipment was rescued from the scrapyard and a lot of the know-how was preserved. In this respect, I believe that while the sound quality of the products of this scene may not always be up to my (admittedly high) standards, they are of major historical significance in the study of the disk record as a medium.

We could perhaps trace the history of this movement in the work of Emory Cook, who realized in the 1950s that certain underprivileged and distant small markets could not sustain a pressing plant in the traditional sense, which needs to produce a certain amount of output in order to be economically viable. These markets had historically been underserved in terms of the availability of recordings to the general public. One of the many innovations of Emory Cook was the development of a press that worked with sintered vinyl instead of extruded vinyl. It was slow, but it could be operated for very small runs. It did not require the usual complex industrial setup around the press, so the idea was that a record store could have one of these in the back room. They could display a catalog of available titles, but not carry any stock, and would press the titles that the customer would choose on demand, while they waited. It was a groundbreaking idea and saw limited implementation in some Caribbean islands.

Pretty much at the opposite end of the world, in the 1980s Peter King in New Zealand put together a custom disk recording lathe and restored a couple of lathes he got from the BBC, using washing machine parts, with the aim of cutting records one by one directly on plastic. After much experimentation, he settled on the use of polycarbonate, of the type commonly used in roofing, and also used the same material to build the roof of the building that housed his workshop!

From Peter King’s website: http://peterkinglathecutrecords.co.nz/history.htm.

Back to the other end of the world, sometime later, Michael Dixon, a lathe cutting artist, lathe restorer, and teacher based in Tucson, Arizona decided to restore vintage Presto (and sometimes other makes such as Rek-O-Kut) lathes. Inspired by the work of Peter King, Dixon cuts records one by one on plastic blanks. Some of these are works of visual as well as sonic art. He has become the Presto lathe expert, restoring and selling these machines and offering advice and training as well as using them himself.

Michael Dixon of Tuscon, Arizona, lathe cutting artist, lathe restorer, and teacher. www.michaeldixonvinylart.com.

This revolution was promptly joined by several others, and coordinated through an internet forum called the Secret Society of Lathe Trolls, created by Steve Espinola, who is known as a restorer of vintage electric pianos under the name Doc Wurly. He started the forum hoping to get some information on a vintage lathe he had found, but it soon attracted every practitioner and expert of the art the world over, and expanded into a major resource of information and a place where ideas can be exchanged.

Others kept on joining in, and younger faces started appearing, thereby ensuring that there is indeed a younger generation interested in carrying the medium into the new millennium.

Steve Espinola, founder/administrator of Lathe Trolls (www.lathetrolls.com), Brooklyn, New York.

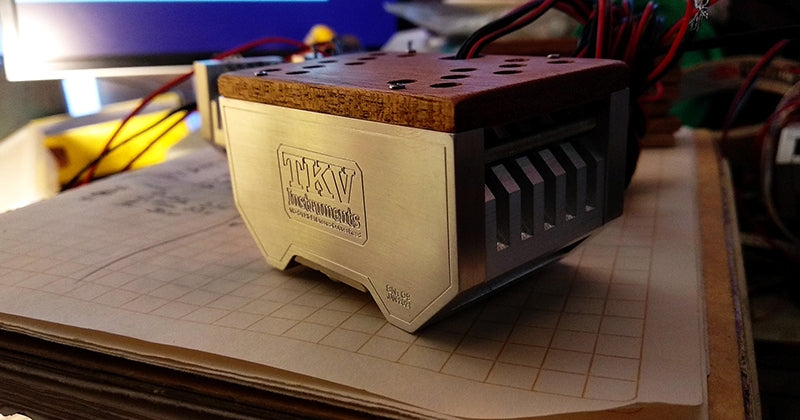

In Mexico City, Konstantin Tokarev started by building his own CNC milling machine. He used that machine to make parts from which he assembled two disk recording lathes of his own design, using a standard consumer turntable as a platter. He then went a few steps further and designed a low-cost stereophonic cutter head, which he is now selling to others.

Hardware from Konstantin Tokarev Assatiani, Mexico City, Mexico. www.instagram.com/kostyantokarev.

John Harris in New Zealand, obviously inspired by the work of Peter King, and located close to where King’s workshop has been for decades, decided to also build his own disk recording lathes, which he also uses to cut records one by one, entirely bypassing the need for pressing plants for small runs of records.

John Harris, Christchurch, New Zealand. www.johnnyelectric.co.nz.

Germany’s Thorsten Scheffner, of Organic Music and its studio, has also built his own disk recording lathe, of a unique design, which he uses to cut master lacquer disks for the traditional process of vinyl record manufacturing. Unlike most designs, Thorsten’s lathe uses a stationary cutter head. It is the platter that advances under the head, in a similar manner to the early lathes of the acoustic era. Thorsten also owns and operates Neumann and Scully lathes, in a facility known for audiophile-grade mastering.

Thorsten Scheffner, Organic Music studio, Obing, Germany. www.organicmusic.de.

Evidently, by now the ecosystem of experimenters is extremely diverse. In the next episode, we will dive further into this world and present a few more of the individuals involved.

Header image courtesy of Konstantin Tokarev.

0 comments