In the fourth quarter of 2021, the Audio Engineering Society (AES) held its annual fall show online. The show’s seminars and interviews were recorded for on-demand viewing, so once again (as was the case in 2020), it was possible to participate virtually.

To recap our coverage so far: in Part Three (Issue 153), Copper covered an extensive interview with art-rocker St. Vincent (Annie Clark), and a symposium on restoring, preserving, and archiving audio for posterity and historical reference, including a look at Elvis Presley’s first-ever acetate recording (currently owned by Jack White). Part Two in Issue 152 featured a talk with keynote speaker Peter Asher (producer for James Taylor and Linda Ronstadt), a seminar on stereo panning and balancing during recording and mixing, and a workshop on controlling low frequencies when tuning a listening environment. Issue 151’s Part One contained interviews with the creators of the iconic OBX-1a and Prophet-5 synthesizers, and a session on PA system optimization protocols.

In addition to Peter Asher, AES had three other fall 2021 keynote speakers: Poppy Crum, John McBride, and Jack Douglas.

Poppy Crum, PhD

Reflecting her background as a doctor of neuroscience, chief scientist at Dolby Labs, and professor at Stanford University, Poppy Crum’s address offered a fascinating perspective on how sounds occur in nature, how the brain reacts to them in order to convey emotion, and how technology can be used to better study and understand these phenomena.

Poppy Crum, PhD.

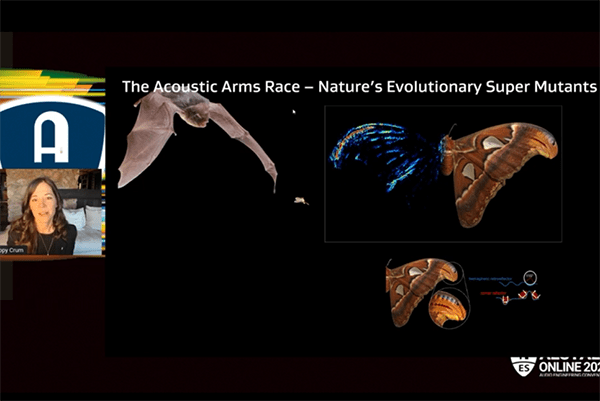

Poppy Crum, PhD.Starting with the evolutionary development of moths in emitting sounds to jam the sonar capabilities of predatory bats, she explained how the moth’s scales act as filters and deflectors of sound that give the bats false directional cues. In another example, she demonstrated how spiders tune their webs like violins, and how the spiders will respond to different frequencies, harmonics, and other audio content, based on the vibrations they feel through their webs. This led to Crum’s questions about how these examples parallel the human brain’s development in reacting to sound.

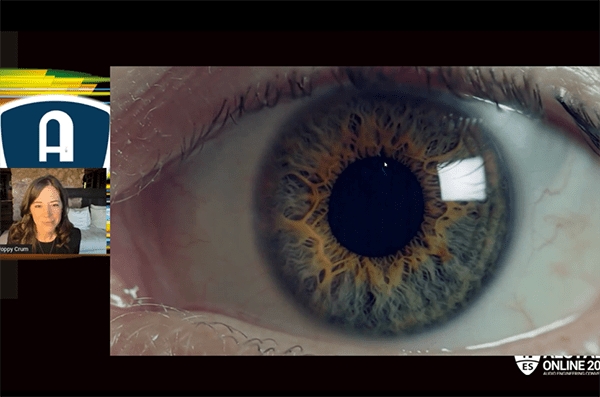

Her next demonstration showed the pupil dilation changes of the human eye as the brain responds to different sounds.

Courtesy of AES.

Courtesy of AES. Courtesy of AES.

Courtesy of AES.

The pupil’s dilation relates directly and autonomically to how hard the brain has to work in response to interpreting intelligibility, volume, and other sonic variables.

According to Crum, measured studies have shown that situational awareness cues and the ways in which our brains react to sound cause us to develop patterns such as changes in breathing, pupil dilation, pulse rates and other factors, that can actually indicate which cities we are from. Other common environmental circumstances that emerge due to logistical exposures over time can include examples like the elevated red blood cell counts found in people who have lived at high altitudes for an extended period of time, and other physical adaptations.

Technology can help us to better understand our cognitive processes, and Crum discussed how technology will shape us in new directions going forward. She cited three points:

1: Neuroplasticity refers to how our brains can actually change and adapt to new environments. New technologies will make us have a faster physiological response time, hear more acutely, see more sharply, think more effectively, and provide other advantages.

2: Empathetic technology will transform the relationships we have with each other, and the spaces where we work, train, heal and live. For example, using biometric signatures to input our personal data into devices, to help us know more about ourselves and our relationship to others and our environment.

3: One-size-fits-all technology will be a thing of the past. Technology has the potential to know more about us than we ourselves know.

Crum cited the example of Elizabeth Cowell, the first BBC TV presenter in 1938. Cowell posed a problem to the BBC engineers, who had standardized a 300 Hz-to-3.4 kHz voice bandwidth for audio, which also was a standard for radio and telephony. This frequency cutoff worked fine for men’s voices, but was insufficient to reproduce the proper harmonics for women’s voices, making them sound shrill, nasal and less intelligible. This technology limitation wound up negatively impacting women in broadcasting until this engineering oversight was rectified.

Crum expounded upon the huge amounts of behavioral data that can be derived solely from how we interact with our mobile devices. Aside from websites that we might choose to view, just the ways in which we type words, listen to earbuds, swipe on touchscreens, and the voices and speech patterns we use to speak into our smartphones could give multiple clues as to our respective medical statuses, and can predict the onset of psychosis, dementia, MS, heart disease, Alzheimer’s and even COVID-19 and other health impairments.

Crum’s work holds that the human ear can be likened to a USB port into our bodies, emotions, subconscious, and to our external world.

Courtesy of AES.

Courtesy of AES.The personalization of our use of technology could be used in a multiplicity of ways to improve quality of life, and monitor for potential problems through AI and computer vision techniques.

From a sound and music perspective, the challenge is in using empathetic technology to stay faithful to a creator’s original intent, and for the technology to communicate and convey all of the meaning, nuance, and emotion behind a recorded performance to each individual listener.

In her work with Dolby Labs, one test Crum mentioned was in measuring listeners’ emotional reactions to music by the changes in their CO2 trace exhalation levels. Listening to musical crescendos resulted in accelerated heartbeats and breathing patterns, and elevated CO2 level traces that could be represented on a graph to determine if the creator’s idea of the music’s intent was successfully realized by the audience’s reactions.

Data privacy and the need for an effective security infrastructure are ongoing concerns that she believes will need to be addressed in order for any technology-based ecosystem to maintain trust with the people being monitored in it.

Crum closed her presentation with a plea for proactivity from those who acknowledged the trends she had identified, in order to shape their direction towards increased personalization but with improved security.

John McBride with Chuck Ainlay

Best known for his work with artists like Mark Knopfler of Dire Straits, Taylor Swift, and Emmylou Harris, producer/engineer Chuck Ainlay has won multiple Grammy awards and has a long affiliation with AES. He interviewed John McBride, owner of Nashville’s Blackbird Studio and The Blackbird Academy, and producer and engineer of multiple platinum and gold records, including those of his wife of 33 years, country music star Martina McBride.

Hailing from Wichita, Kansas, McBride got his start right after high school running a live sound system rental business operated from his van. He noted that back in the day he would rent Yamaha monitor speaker wedges for $5 a day each.

Displaying canny business instincts at a young age, McBride was able to apply for a $75,000 loan through the Small Business Administration program in the early 1980s, in order to acquire the equipment needed for a professional sound system that could service outdoor festivals and larger indoor arenas. Thanks to his parents agreeing to collateralize the loan with their home, McBride was able to score a regular rental gig at the Cotillion Ballroom, which was a hub for all kinds of country, rock, pop and R&B acts in the Wichita area. This gave him ground-up audio training in working with all kinds of musical artists. The early days were a financial struggle; McBride laughed that at the time he began dating Martina in 1987, he was still sleeping on a couch in his warehouse because he couldn’t yet afford his own apartment.

John McBride. Courtesy of AES.

John McBride. Courtesy of AES.As McBride’s sound touring company grew to become one of the best mid-sized ones in the US, he and Martina decided to move to Nashville in 1988 and set about plans to make a demo for her to get a record contract, and for building a recording studio. In 18 months, Martina had her record deal, while John McBride had become production manager for Garth Brooks.

McBride’s introduction to Brooks was through bassist Mike Chapman and in McBride’s company providing sound for Ricky Van Shelton, for whom Brooks was an opening act at the time. After McBride’s move to Nashville, Brooks would use McBride’s services whenever possible and rehearse at his warehouse.

In 1991, when Brooks’ career skyrocketed to playing huge arenas, McBride told him that Brooks’ requirements had outgrown his sound company, and that he either needed to hire a larger company or lend McBride the money for expansion, which Brooks readily agreed to do.

As this was at the time when suspended line array loudspeakers began to become prevalent (as opposed to the earlier use of ground-stacked sound reinforcement systems), along with computerized sound and lighting, McBride recalled the steep learning curve that he needed to master for Brooks’ upcoming tour, jokingly telling Brooks, “Garth, I need to start charging you more so I can pay you back!”

McBride eventually sold his touring sound company to Clair Brothers in 1997. At the time, the McBrides were finally able to pay off their debts, and Martina’s career would take off by 1999. McBride decided to look into building a recording studio, and found a location: the former Creative Workshop Recording studios, which in its heyday had been the source for a number of Kenny Rogers hits, but had since fallen into such disrepair that it was reduced to recording jingles. McBride took over the studio in 2002.

Chuck Ainlay. Courtesy of AES.

Chuck Ainlay. Courtesy of AES.As he felt that Nashville was looked down upon by music industry people from the coasts, McBride’s competitive streak drove him to create Blackbird as a facility that could outdo any studio in Los Angeles or New York. His goals were to be able to offer any artist from any musical genre a place where any musical idea could be realized to its fruition, and that the sound quality would be undeniably good.

As a former roadie, McBride’s credo with Blackbird is, “always have spares for spares. I never buy one of anything!” His philosophy is that he never wants any artist or engineer to not have a piece of gear with which they need to create. This has led to Blackbird’s incredible mic collection and its fabled inventory of prized vintage sound-processing equipment.

In 2013, McBride formed The Blackbird Academy with Mark Rubel and Kevin Boettger, after finding that interns from other expensive audio engineering programs didn’t know how to mic a drum set. McBride set out to create a six-month educational program where graduates would have the skills to work on a Dann Huff record (Huff is a noted country music producer and songwriter) and work with top sound reinforcement company Clair Brothers on a live gig. He proudly boasted that 90 percent of Blackbird’s graduates are working on live shows, while 73 percent are working in recording. McBride believes this is one of the best ways to give back to the industry – provide the skilled people to continue its operation for the next generation.

McBride also praised the networking aspects of AES that enable even pros like himself to learn more, and cited his meetings with legendary producers Geoff Emerick and Phil Ramone as examples. He regards mentoring as a crucial way to accumulate critical knowledge, and mentioned how Emerick explained to him the secret to The Beatles’ piano sound on “Lady Madonna” – an AKG D19 mic as close to the soundboard of a 7-foot grand piano as possible, and then crushing the sound with Fairchild and Altec compressors.

John McBride (right) with Chuck Ainlay (left). Courtesy of AES.

John McBride (right) with Chuck Ainlay (left). Courtesy of AES.His philosophical credo is, “good is the enemy of great.” If he had never strived for excellence, McBride believes Blackbird would have already gone out of business, and that kind of work ethic is what keeps his edge. He has vowed never to retire, and since he is so passionate about music, he readily admitted he would pay money to get to do what he does. In keeping with this mindset of excellence, McBride’s latest Blackbird addition is a Dolby Atmos immersive mixing room designed by George Massenburg.

Jack Douglas and Finneas

Finneas is a talented singer, songwriter, producer and actor, and is the engineering and production powerhouse behind the multi-platinum records of his sister Billie Eilish, and more recently, the title song from the latest James Bond film, No Time To Die.

A music industry legend, Jack Douglas was one of the original Record Plant East engineers in New York City during the 1960s and 1970s, working with Roy Cicala, Shelly Yakus, Dennis Ferrante, Jimmy Iovine, and others. His iconic records with Aerosmith, Cheap Trick, Alice Cooper, and John Lennon are heralded around the world.

Douglas spoke with Finneas about his production of “No Time To Die,” and they compared notes between Finneas’ Gen-Z DIY approach and Douglas’ old-school professional studio production and engineering methods.

Jack Douglas with FInneas. Courtesy of AES.

Jack Douglas with FInneas. Courtesy of AES.Finneas noted that he and Eilish were given 20 pages of the Bond screenplay and asked to compose the song based on plot elements as written, long before the film started production. Even though the song had been completed in 2019, the pandemic delays would postpone the release of No Time To Die until 2021. Orchestrations were recorded with Hans Zimmer at AIR Studios in Montserrat.

Finneas showed off his home studio, which was designed by Blake Douglas, Jack’s son.

Douglas noted that in his day, studios needed to have backup hardware gear for everything, and daily maintenance crews were the standard. Noting how Blake has developed a reputation as a DIY studio troubleshooter, he commented that the big shift towards software-based recording has reduced many of the old-school requirements to being optional, as opposed to absolutely necessary in order to make records.

In contrast, Douglas recounted the laundry list of vintage equipment in his studio (shared with producer Jay Messina), such as Fairchild compressors, Pultec tube equalizers, Spectrasonics mic preamps, Telefunken microphones, and Studer A-80 multitrack recording decks.

Finneas exclaimed that the production on the John Lennon and Aerosmith records had aged well and would be considered innovative if released today. Douglas replied that when he became a producer, he felt that every song’s production should stand on its own to best service the song, similarly to how The Beatles’ White Album contained a wide range of sounds and production approaches. This would involve tuning the drums’ toms to the key of a song, for example. Douglas also credited his time as an engineer working with producers like Phil Ramone, Eddie Kramer and Phil Spector as important educational periods that trained his own production sensibilities in working with artists, in how to serve a song, and in how to use mics to re-create a particular desired sound of an instrument or voice. He stressed that one needed to be satisfied with how something sounded when played back in the room, before reaching for any EQ or other processing.

Unlike his friend Bob Ezrin, who is known for his production sound with Pink Floyd, Lou Reed, and Alice Cooper, among others, Douglas prides himself on not having “his own sound,” so that his production work will be faithful in presenting the artist and their work in the best context.

Finneas noted that Douglas has had a number of repeat clients, which is a credit to the kind of rapport he has been able to build with artists over the decades. Douglas attributes this kind of trust to his willingness to try the artist’s ideas, no matter how outlandish or ridiculous they might be, as long as it might lead to a better performance.

Douglas noted that because studio time was so expensive, pre-production time in developing songs when a band like Aerosmith had just finished a tour could be laborious and take months. He admired the fact that Finneas could work with an artist in writing a song from scratch and then swiftly completing it to the point where a demo could be made that could be turned quickly into a record, thanks to modern technology.

Douglas recollected that in producing the Aerosmith album Rocks, the band had been rehearsing in a warehouse with awful sound, which Douglas then took weeks to properly treat to make it sound good. He became concerned that the material the band was creating was tuned to the sound of the room and that it would lose its vibe if they moved to a studio, leading to the decision to hire a remote truck to record the album in the warehouse.

On the other hand, pre-production on John Lennon’s Double Fantasy had to be conducted with the identity of the artist remaining secret until Lennon felt the songs were ready. Douglas’ workaround involved his making charts for all of the musicians selected for the record, recording them on cassette with Douglas singing the lead vocals, and then submitting the cassettes to Lennon for approval or further tweaks. He credited the trust that John and Yoko Ono had in him to his Record Plant days when he had worked with them on Imagine and on all of Yoko’s solo records.

Both Douglas and Finneas admitted that they rarely, if ever, know what the single from an album should be, and marveled at producer Jimmy Iovine’s knack for being able to hear the single – a talent which led to his successful career at Interscope Records. Douglas recalled that the only time he felt he knew what song would be a hit single was when he first heard Lennon play “(Just Like) Starting Over” on piano, which the former Beatle had been hesitant about showing him and which almost didn’t make it onto the album.

Billie Eilish and Finneas. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Justin Higuchi.

Billie Eilish and Finneas. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Justin Higuchi.

Finneas has a solo album scheduled for release, and he was excited about producing an upcoming project with British artist FKA twigs. He lamented how the music industry is now focused mostly on singles as opposed to albums. He also noted his affinity for analog gear – even though he works in digital, he still records sister Billie’s vocals with a vintage Telefunken 251 mic and a Neve preamp. He admitted that although he has access to vintage gear, he needs to spend time with someone like Blake or Jack to teach him how to use it properly.

They concluded their talk with comparisons about their production experiences with other artists and on favorite soundtracks of late, with Douglas citing the 1994 Luc Besson action flick The Professional and Finneas rhapsodizing about The White Lotus HBO series.

AES is to be commended on yet another excellent series of educational seminars. While it will be exciting to return to in-person events in the future, in-depth coverage of presentations like these offer the advantage of being able to be viewed repeatedly and in depth, thanks to on-demand streaming.

0 comments