(Copper Issue 166 featured coverage of AES Europe Spring 2022 presentations that included a look at the intricacies of tuning high-performance audio systems for automobiles; a study on the changes in how consumers use headphones, and advances in headphone technology; and a look at the challenges of mixing immersive audio content to stereo while minimizing loss of spatial perspective in the sound field. Copper Issue 165 reported on presentations on the use of analog versus digital equipment in recording studio mixing; a look at the trend towards mobile audio wearables; and the challenges faced by engineers in archiving and restoring audio from analog disc recordings. Although AES Europe Spring 2022 was held in The Netherlands, the wonder of digital streaming enabled people to cover and participate in the show remotely. This is the final installation of our AES Europe 2022 reporting.)

The Art of Cutting a Vinyl Master

Presented by mastering engineers Maggie Luthar (Soccer Mommy, Redd Kross) of Welcome to 1979 and NPR, and Jett Galindo (Barbara Streisand, Weezer, Selena Gomez) of the Bakery, The Art of Cutting a Vinyl Master was a fascinating look at how vinyl, once predicted to share a similar demise with Betamax tape, has once again become a commercially viable music listening medium.

Jett Galindo with Maggie Luthar. Courtesy of AES.

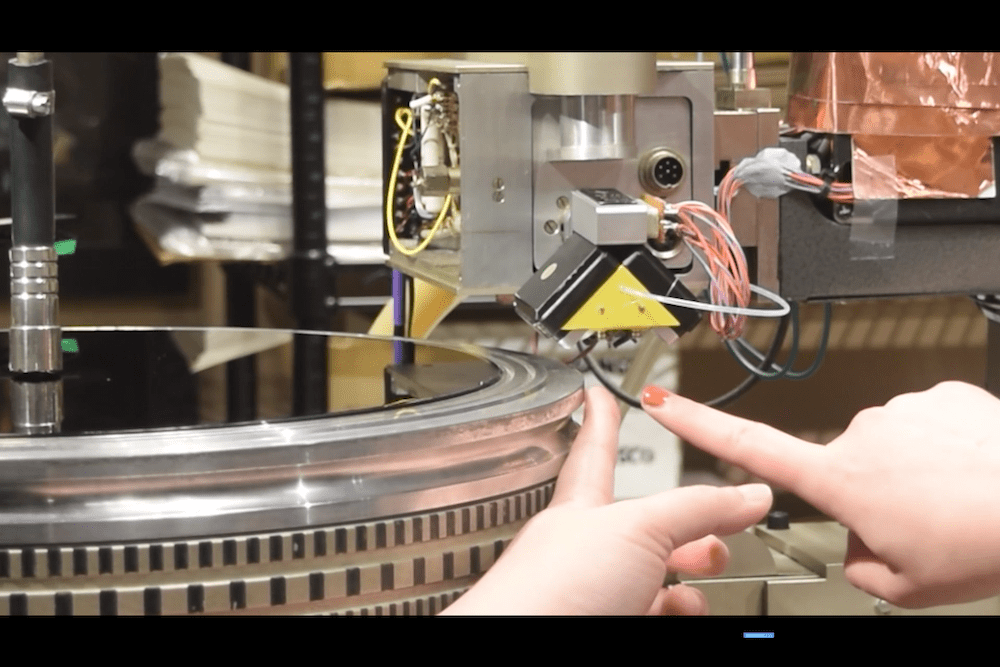

Galindo noted that the Neumann VMS70 cutting lathe with SX74 cutting head she was demonstrating has been customized and modernized to better accommodate modern music, and contains both brand new parts as well as vintage ones in order to combine the best of both worlds. Galindo conducted the demo as follows:

- Selecting a blank 14-inch lacquer disc, she cleaned it of any surface dirt with compressed nitrogen before placing it on the lathe’s platter.

- During the record cutting process, a vacuum attachment is used to remove the lacquer residue caused by the cutter head carving the sound vibrations (grooves) onto the lacquer master disc.

- Galindo explained that RIAA equalization curve guidelines for vinyl mastering require an attenuation of low frequencies and a boost of higher ones. This is because RIAA playback parameters call for a reverse of that curve in order for the playback to theoretically result in a flat response. The use of the RIAA curve was also the result of commercial considerations, since lower frequencies take more space on a disc (i.e., wider grooves), so the parameters were created as a compromise between optimum sound quality and getting a long-enough playing time onto a record side.

- Galindo also explained that mastering at half-speed not only helps with detail reproduction accuracy, but also puts less stress on the cutting head, since higher frequencies carry more energy. Half-speed mastering also results in clearer transients and a perceived boost in loudness.

- The feed from the original sound source (in this case, a Pro Tools session) is split into two signals: a Preview track, which is fed into the cutting lathe, where an internal computer sees the signal seconds ahead of time in order to mechanically adjust for level, groove spacing, etc., and a Program track, which is the actual signal that winds up being used by the cutting head stylus to cut the lacquer master.

- While older cutting lathes are not as automated as Galindo’s VMS70, she said that, while she doesn’t have to tweak things or press buttons on the fly as much as with a vintage machine, certain situations, such as a when there is a drastic dynamic change between two musical passages, will call for her to engage an “echo” button. It creates a barely-audible “ghosting” effect, but will keep the stylus from jumping too wildly and possibly out of the groove, thus ruining the master. It’s also engaged at the end of a musical program to make sure that it doesn’t inadvertently spill over onto the next track.

- Once a session is completed, Galindo said that she will examine the freshly-cut lacquer master under a microscope to visually inspect the grooves. She said that she looks for indications of overlapping or grooves that are cut too narrow, both of which will result in flawed discs.

- Luthar mentioned that the art of vinyl mastering is in the delicate balance between volume level, frequency content, and the space between the grooves. When the program is longer, then the level needs to be quieter in order to fit more running time onto each side of the master.

Galindo cleans a blank lacquer disc with nitrogen. Courtesy of AES.

Close-up of the SX 74 cutting head. Courtesy of AES.

The next step in the process is sending the freshly-cut lacquer master out for electroplating. A “mother,” which is a metal-disc inversion of the master, is created in order to stamp the actual vinyl records.

Luthar holds an example of a “mother” for stamping new records. Courtesy of AES.

When preparing source files for a mastering session, Luthar and Galindo reviewed the options, techniques, and tools that mastering engineers have at their disposal. Additionally, they dispelled some myths about the process. Some of their key points included:

- Vinyl mastering houses can easily work with the same digital master used for CDs or streaming; a separate digital master for vinyl is unnecessary.

- Certain genres of music that may have unusual sounds, like avant-garde jazz or some forms of hip-hop, benefit from having the mastering engineer communicate with the cutting house to make them aware of which sounds are intentional, in order that the content doesn’t get altered due to the cutting engineer mistaking the unusual sounds for errors that require correction!

- The geometry of vinyl is such that the portion of the groove that is closer to the center is smaller in diameter than on the outer perimeter of a disc. Sibilance, which often finds its way onto DIY recordings, may not be so noticeable on the earlier songs that are cut on the outer grooves, but can become an increasing threat to sound quality towards the end of a record’s side, as the distortion becomes much more apparent when the grooves are compacted (the diameter of the grooves decreases).

- The quality of a playback stylus can vary widely between record players. As a result, the perception of distortion on one system vs. another can often be traced to the limitations of a playback system, rather than any inherent problems with a vinyl master. Good vinyl-cutting engineers will often have to compromise on fidelity in order to get the master to create a mother that will sound good on lowest-common-denominator turntable setups.

- As the sequence of songs and their respective degrees of high-frequency content can have a bearing on the final sound quality heard on the vinyl, artists need to communicate with their vinyl mastering engineers to familiarize themselves with the options: reducing the level to preserve the high-frequency content; keeping the level constant and acknowledging it will result in some distortion; or re-sequencing the track order, in order to maintain the best-possible fidelity for each song over the course of a side (some tracks that are less-dynamic or have less high-frequency content will “suffer” less if located at the end of a record side).

Techniques that a vinyl cutting engineer may deploy include:

- De-essing (to decrease sibilance, a technique that should be used sparingly).

- Decreasing the amount of low-frequency stereo (in favor of more monophonic bass), to preserve groove space and to maintain a balance with mid- and high-frequency content during the lacquer-cutting process.

- Changing the track order. (The aforementioned sibilance issue is also one reason why vinyl albums would have the high-energy hit songs earlier on a record, and the ballads or other music with less high-frequency content towards the end of a side.)

They noted that managing expectations is another topic that frequently comes up, especially since there are now two generations of artists who were likely not raised on vinyl records. Some of these include:

- Running times: for optimum sound quality, the ideal length of one side of a vinyl record is between 18 and 20 minutes. Classical records may sometimes sacrifice some fidelity in order to squeeze an extra 4 to 5 minutes onto a side, but anything longer than that will result in noticeably compromised audio quality.

- Any unusual aspects of a record need to be communicated to the intended audience. Galindo cited the example of Taylor Swift’s vinyl release of her Red album, which was intended for playback at 45 rpm. A sizable portion of her audience, for whom this might have been their first-ever vinyl purchase, complained and returned the record because they were listening at 33-1/3 rpm, unaware that their turntables had 45 rpm playback capability!

- Galindo advised that one of the best ways for an artist to avoid problems when creating a vinyl master is to create a complete .WAV file for each side of the proposed record with all of the tracks sequenced, spaced, labeled, and timed.

- Preparing a chart (similar to a PQ sheet for a CD master) with all of the running times for each song, as well as the time for the gaps between songs, ensures that the cutting engineer won’t have to guess and avoid situations where a song might have intentional silence in the middle, which the engineer might think was the end of a song.

- Any elements of intentional distortion or other noise on a digital master may be exacerbated on vinyl due to analog format limitations, so artists need to acknowledge this in advance and communicate with the cutting engineer accordingly, if the engineer needs to tone the sound down with EQ or other means in order to preserve fidelity.

Galindo and Luthar concluded that the better communications are between engineers and artists when translating music onto vinyl, the greater the likelihood of good results all around. They exclaimed that since “engineers work like hermits and rarely get to talk to anyone new,” they’d probably welcome queries from interested artists!

Simulation-Based Acoustic Design for a Modern Urban Church Sanctuary

Simulation-Based Acoustic Design for a Modern Urban Church Sanctuary was presented by students Patrick Judy and Andy Morgan, along with acoustic consultant Dr. Braxton Boren of American University.

While houses of worship may be designed in similar ways to concert halls, Judy points out that although architectural acoustics may have a bearing on the construction, there are idiosyncrasies that can often make some church spaces diverge widely from the techniques used for concert hall acoustics. Some of these include:

- A preference for the sound to echo and surround a congregation, rather than an emphasis on the sound emanating from a specific area.

- The choice to employ or eschew sound reinforcement, as well as certain instruments that might require it (for example, synthesizers) or are designed to be heard acoustically on their own (such as pipe organs and pianos).

- The priorities, values and traditions of the particular faith inhabiting the space.

Redeemer Presbyterian Church photo model. Courtesy of AES.

Judy categorized the acoustic priority divergence among houses of worship into two camps:

Semantic: speech clarity, open-air, free-field

Aesthetic: mystery, cave, diffuse-field

Judy mentioned that an increasing number of houses of worship might alternatively hold classical services and contemporary services, with the sonic demands from the two music genres and liturgies often coming into conflict.

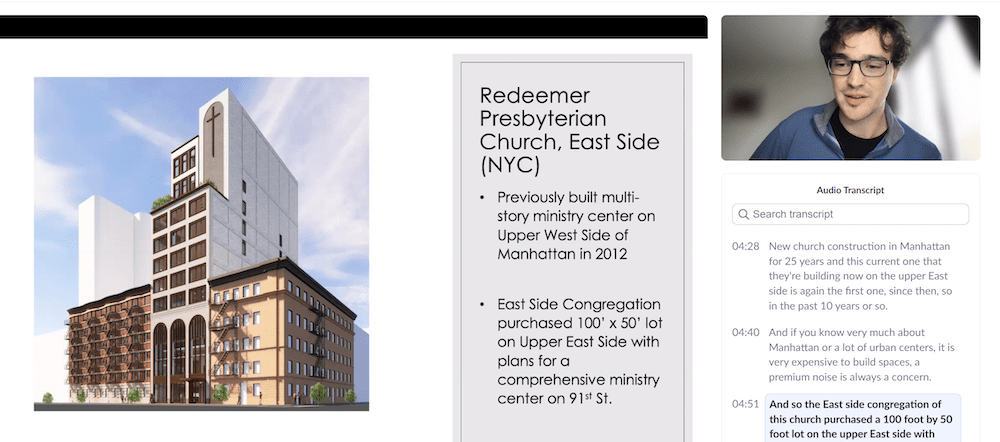

Referencing the latest acoustic design technologies in new church construction, Judy cited Redeemer Presbyterian Church in New York City. The first Redeemer Church was built in 2012 on the West Side of Manhattan. Created as a multi-story ministry center, it was the first new church built in New York City in 25 years. The new East Side facility is being constructed on a 100-foot by 50-foot lot on East 91st Street.

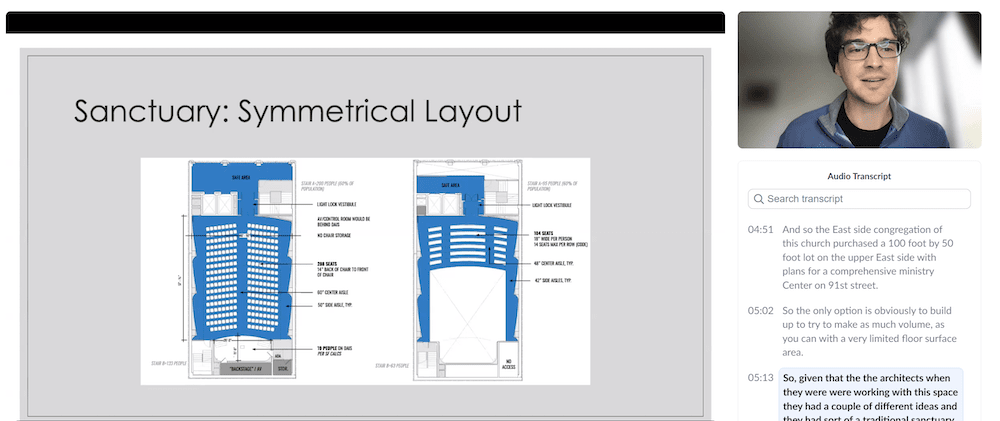

Given the cost of real estate in New York, going vertical versus horizontal was decided upon as the most expeditious way to maximize the volume level (SPL) and sound quality within the space. The acoustical engineering designers at first decided on a traditional “shoebox” configuration. The general familiarity of that shape allowed for certain standardized ballpark metrics with regard to diffusion requirements, dealing with sound reflections in parallel wall spaces, and other considerations.

Original layout blueprints for the new Redeemer Presbyterian Church. Courtesy of AES.

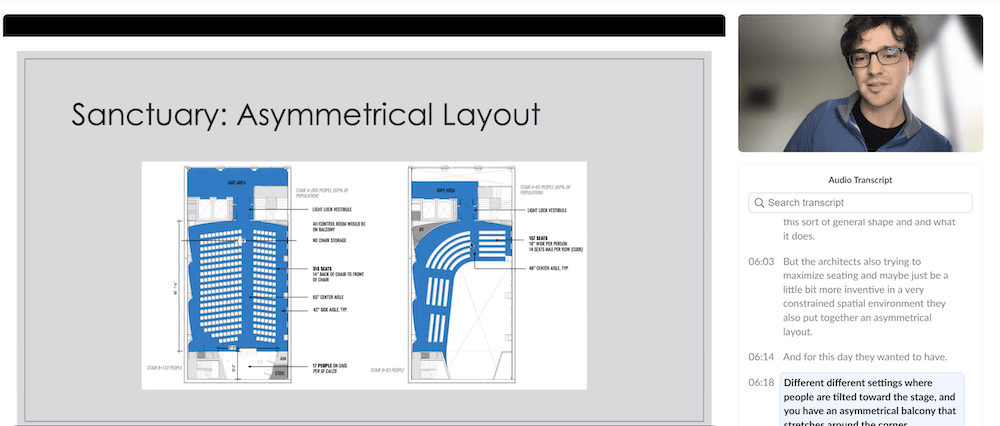

However, further research led them to plan an asymmetrical layout that would offer improved sound and better seating views.

Asymmetrical layout blueprints for the new Redeemer Presbyterian Church. Courtesy of AES.

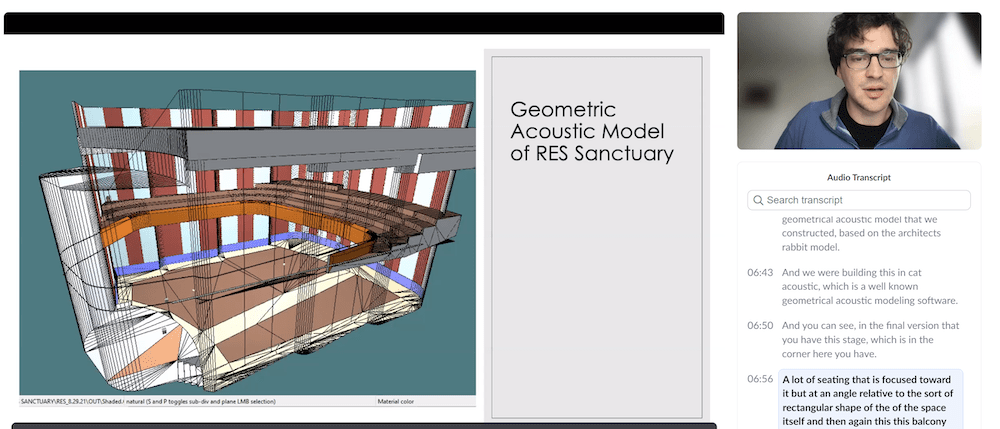

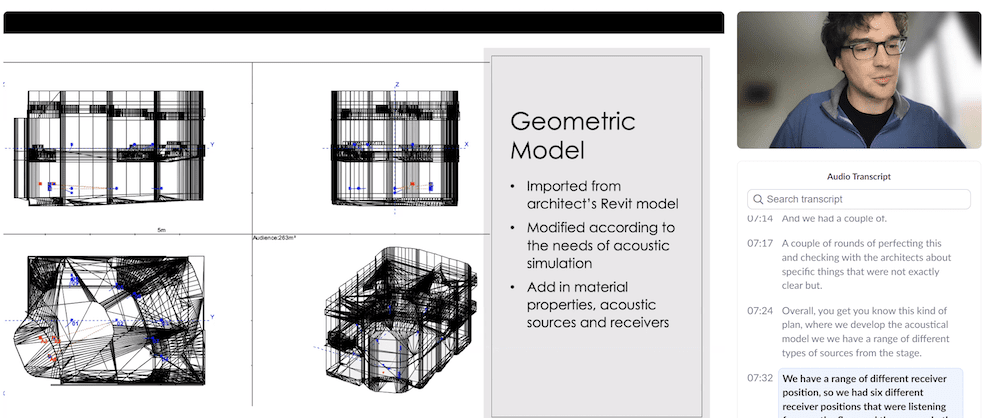

Judy noted that they tested sound sources with “a range of different receiver positions, so we had six different receiver positions that were listening from on the floor and three more in the balcony, a total of nine different listening positions around the virtual model.” The CATT-Acoustic modeling software they used was crucial for making adjustments in the virtual world, without the cost outlay of building physical structures that might have to be discarded and rebuilt differently.

Incorporated into the design were Redeemer Church’s reverberation time variants:

3D Geometric Model of Redeemer Presbyterian Church. Courtesy of AES.

- Speech and gospel music requires a fairly short reverb time of 1 second.

- Classical music generally demands a reverb time of over 1.5 seconds.

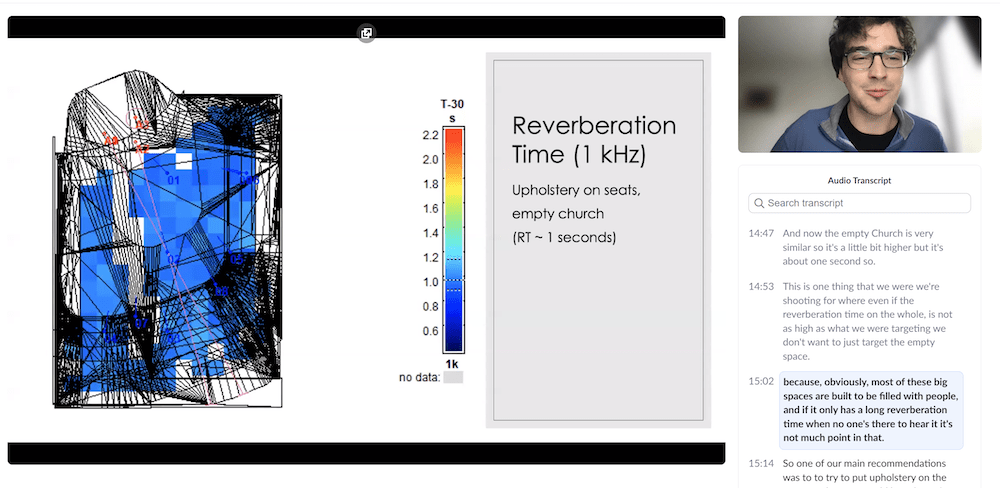

- The difference in reverb times should be barely noticeable between when the space is occupied and unoccupied.

Some acoustic simulation models for Redeemer Presbyterian Church. Courtesy of AES.

These parameters came about as a result of cumulative feedback from artists and listeners at Redeemer’s West Side structure, which has a reverb time of nearly 2.5 seconds and was deemed comfortable by classical artists looking for acoustical support from the space, but excessive by a number of contemporary music artists that prefer more of a “dead” space where artificial reverb and delay can be deployed as desired.

The orange and white color scheme chosen for the acoustical absorption panels was not only visually appealing, but the fabrics conceal a range of alternating acoustic absorptive (1-inch fiberglass) and reflective (hard gypsum) surfaces designed to remove bass build-up and break up standing waves, respectively. The angled reflective panels also serve to minimize reflections from parallel surfaces.

After getting the CATT model tweaked to design the space with a reverberation time of roughly 1.4 seconds with hard seating in place, they managed to pare down the reverb time differential between when the sanctuary is occupied and unoccupied to only 0.2 seconds, thanks to the addition of upholstery to the seating.

Reverberation time graphic image of Redeemer Presbyterian Church interior. Courtesy of AES.

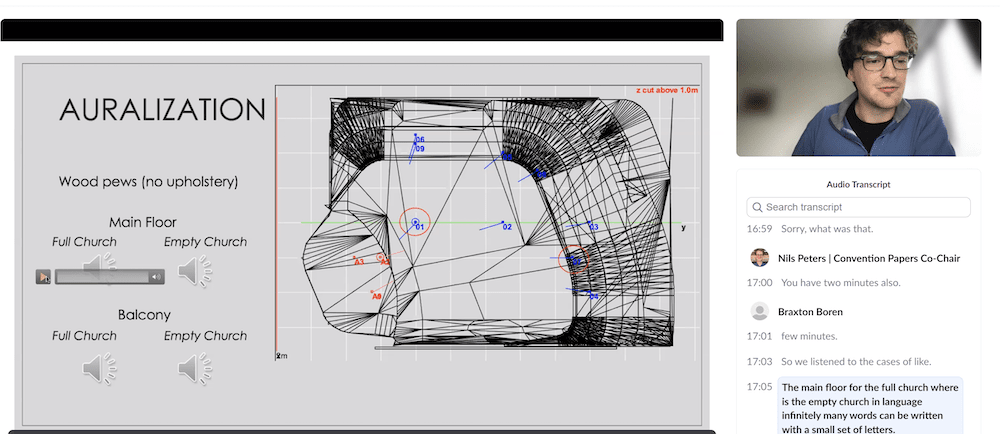

The last step was to create test anechoic recordings for both speech and performed music using the reverberation calculations for how sounds would manifest themselves in the various virtual room simulation options (occupied vs. unoccupied space, wood vs. upholstered pews, floor vs. balcony) and use these recordings to get approval from the clients.

The use of CATT simulation software to calculate the acoustic reflections in a virtually modeled space is a huge technological advantage that today’s sound designers have over their predecessors. Judy, Morgan and Boren have completed an engineering accomplishment that will mark a historic breakthrough for New York house of worship architecture and design when Redeemer Presbyterian Church’s East Side structure is slated to be finished in late 2023.

With the events and seminars of AES Europe Spring 2022, the Audio Engineering Society has once again made significant contributions to our knowledge of audio technology.

Test recording sample file for different reverberation/room options. Courtesy of AES.

0 comments