“Murder Most Foul,” Bob Dylan’s newly released song, is long. It is 17 minutes and change, about as long as “Desolation Row” and “Like a Rolling Stone” combined.

It is Bob’s longest single studio recording, coming in about 23 seconds longer than the entertaining Dylan dream that was “Highlands” from 1999’s Time Out of Mind. I’ll always have a fondness for “Highlands,” for its scene in a coffee shop, where the waitress bets Dylan that he doesn’t read women writers. As a retort, Dylan rhymes “wrong” and “Erica Jong.”

“Murder Most Foul,” released on March 27, 2020, is not a new song or recording, but is said to have been written and recorded around the time of “Tempest,” which would place it in 2012. Dylan’s office, which has always been as accommodating as Bob will allow, could not add anything to the notice on the home page of the official BobDylan.com.

On the right side of the home page is an emblematic photo of President John F. Kennedy, as seen in pride and sorrow as part of the interior decorating scheme of a vast number of American, especially Irish-American, homes, ever since his election, and his death. Inscribed at the bottom of the photo, in a kind of gothic typeface, is the song’s title. On the left, Dylan offers three brief sentences of introduction.

“Greetings to my fans and followers with gratitude for all your support and loyalty across the years.

This is an unreleased song we recorded a while back that you might find interesting.

Stay safe, stay observant, and may God be with you.”

Musically, it is sparse, slow, just a few piano notes and a violin or viola or similar string instrument, with a few faint drum rolls later on. A funeral procession.

The song operates on two parallel themes. Full of rage and anger, the essential theme is the assassination of JFK on November 22, 1963. It is very serious, thrusting in its accusations, skepticism and sarcasm that give life to the only serious conspiracy theory that deserves its oxygen: the notion that Lee Harvey Oswald was not the sole assassin, perhaps not even the assassin. In this theory, Oswald was the “patsy” (or as Dylan free associates, “the Patsy Cline”), the fall guy for a conspiracy of many moving parts, a crazy scheme, really, to kill the president, and which all came together hellaciously well. “They blew off his head while he was still in the car/Shot down like a dog in broad daylight/Twas a matter of timing, and the timing was right.”

The plot, according to the majority of the American public that still believe in the conspiracy, involved so many unsavory members of American institutions—the CIA, the FBI, the Pentagon, the Mafia, a militia of anti-Castro Cuban emigrés, the Teamsters—that the only option has been to cover up the truth for the last 57 years. “What is the truth, where did it go? Ask Oswald and Ruby, they ought to know,” Dylan sings.

Oswald, for those arriving at this movie late, was shot to death at point blank range by small time Dallas strip club owner Jack Ruby on live TV in the middle of Dallas police headquarters while being transferred to another part of the building two days after the assassination. Ruby died of cancer in jail in 1967, insisting until the end that he killed Oswald out of patriotic rage.

The lyrics, as published on bobdylan.com, are in four numbered sections of varying lengths. The first three mix details about the assassination, and the Sixties pop culture explosion that would follow his death, in the form of imagined thoughts and visions of a dying Kennedy. Some are in the form of telephoned requests to disc jockey Wolfman Jack, a New York hustler (real name Bob Smith), who pursued the big bucks through the big beat with a big howl and 250,000 watt (five times the FCC limit for American stations) XERF, its transmitter based in Ciudad Acuña, Mexico, across the Rio Grande from Del Rio in southwest Texas. Wolfman played R&B for teenagers on a signal that could be heard across North America, and on a clear night, around the globe, while also selling mail order products, including live chickens.

Wolfman Jack is introduced as the vehicle for JFK’s life-ebbing hallucinations at the end of the first section: In the last four standalone lines of section one, Dylan calls JFK’s murder the “Greatest magic trick ever under the sun, perfectly executed, skillfully done. Wolfman, oh Wolfman, oh Wolfman howl.” Comparing the assassination to a magic trick may be one reason why, near the end of the song, there is a vision of “Houdini spinning around in his grave”: As if history’s most renowned magician and legendary escape artist never matched the trick Kennedy’s killers pulled off.

Pop culture geeks will be able to get happily lost in the many musical references criss-crossing Kennedy assassination minutiae. Section two introduces the Beatles, name drops Woodstock, Altamont, the Aquarian age, as Kennedy’s limousine races for Parkland Hospital. Section three begins: “Tommy can you hear me, I’m the acid queen…Ridin’ I the back seat, next to my wife/Heading straight on into the afterlife.”

There are images of surgeons trying to save Kennedy’s life, removing his brain, and of the only known real time images of the assassination, known as the Zapruder film. “It’s vile and deceitful–it’s cruel and it’s mean,” Dylan sings, with palpable disgust.

It is a lamentation in the literal sense, an expression of grief, in the Biblical sense. In the Old Testament, the Book of Lamentations is a series of poems or songs of deep sorrow attributed to the prophet Jeremiah, decrying the destruction of the first Temple in Jerusalem in 586 BCE and the beginning the Babylonian exile of the Jewish people. The Book of Lamentations is read, and sung, on the saddest day of the year for observant Jews: Tisha B’Av, the ninth day of the month of Av on the Hebrew calendar, which remembers the destruction of both Jewish temples. (Some believe that Jeremiah wrote the Lamentations before the destruction of the first temple, but its destruction was his prophecy.)

The original Lamentations consisted of four chapters, which is perhaps why “Murder Most Foul” has chapters numbered one through four. (A fifth was written later.) The depravity and idol worship, the moral decline of his people that tormented Jeremiah, are echoed by some of what Dylan writes, at the beginning of his chapter four: “What’s New Pussycat…what’d I say/I said the soul of a nation has been torn away/It’s beginning to go down into a slow decay/And that it’s 36 hours past Judgment Day.”

From that point, the rest of chapter four is the longest, at about 80 lines, about three times longer than the other chapters. That also suggests Jeremiah, whose chapters one, two and four contain 22 lines; chapter three, 66 lines. Dylan is not writing with quill and parchment here. Almost all of it seems to be riffing out the rhymes for the sake of rhymes, shouting out song titles, movies, plays, artists. It reminds me of the annual Christmas poem “Greetings, Friends!” in The New Yorker (written for many years by Roger Angell, more recently Ian Frazier), which offers holiday gifts and wishes to friends and the famous using jocular rhymes, such as this one by Frazier from December 23, 2019:

“[For] Michael McFaul, Billie Eilish—

Socks by the carload, highly stylish.”

Dylan implores the Wolfman:

“Play Oscar Peterson and play Stan Getz

Play ‘Blue Sky,’ play Dickie Betts.”

He also sings: “Play Don Henley, play Glenn Frey/’Take it to the Limit’ and let it go by.” Dylan’s invocation of the Eagles could start another conspiracy theory: is it praising, or rhyming lazy? But we don’t want to go there.

Dylan released a second song, “I Contain Multitudes” on April 17. Its title comes from one of Walt Whitman’s, from “Song of Myself, 51”: “Do I contradict myself?/ Very well, then I contradict myself/ (I am large, I contain multitudes.)”

He has always embraced his own contradictions, and this rueful song, lightly flavored with pedal steel, Dylan states some of them proudly. “I sing the Songs of Experience, like William Blake/I have no apologies to make.” He acknowledges his dark side, as boastful as any rapper: “I carry four pistols and two sharp knives.” It’s almost like Dylan’s “My Way”; although his singing is understated, the lyrics bite with a rapper’s ferocity. “I’m just like Anne Frank, like Indiana Jones/And them British bad boys the Rolling Stones,” he sings. Come on, Kanye, step up, Drake: This Bob’s for you.

All Dylan lyrics © 2020 by Rider Music.

Whitman, “Song of Myself,” public domain.

“Greetings, Friends!” © The New Yorker magazine.

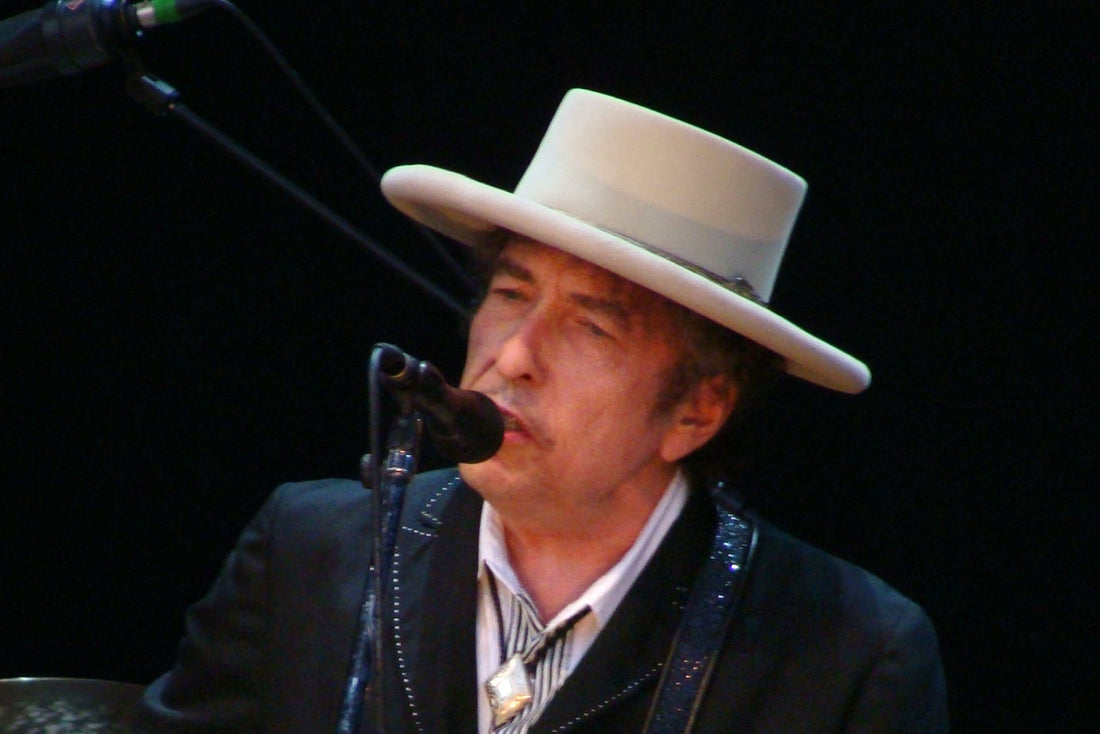

Bob Dylan photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Alberto Cabello.