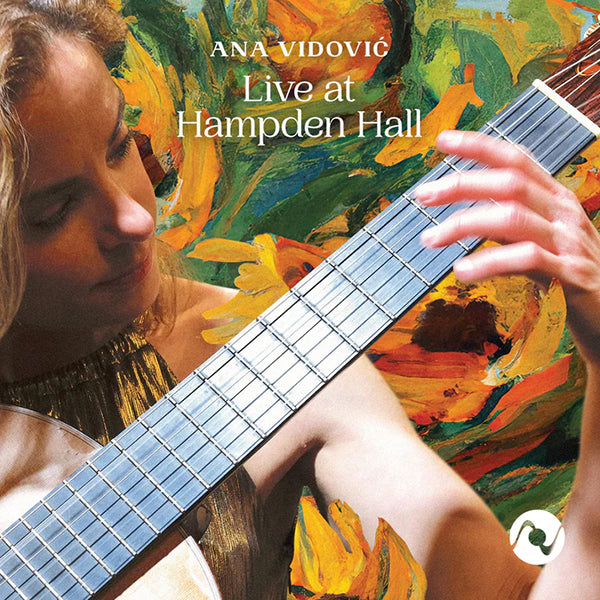

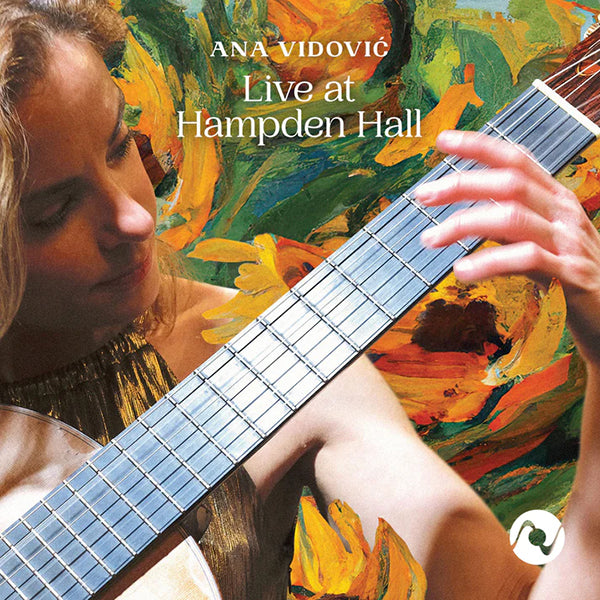

Octave Records is honored to present internationally-acclaimed classical guitarist Ana Vidović on its latest release, Ana Vidović Live at Hampden Hall. Recorded with impeccable clarity using Octave’s Pure DSD 256 process, the album features Vidović in an intimate live setting performing a two-disc set of works by J.S. Bach, Barrios, Scarlatti, Sor and other composers.

Ana Vidović has been hailed as one of the world’s finest classical guitarists. She began playing at age eight and became the youngest student to attend the Academy of Music in Zagreb, Croatia. She has appeared at recitals, concerts and festivals worldwide and won numerous international awards including the Fernando Sor Competition in Italy, the Francisco Tarrega Competition in Spain, the Eurovision Competition for Young Artists, and many others. She is a graduate of the Peabody Institute.

Vidović plays with a beautifully expressive, rich tone, where notes seem to bloom out of her instrument, an Australian Jim Redgate guitar. Vidović said, “Guitar is a very interesting instrument with such a wide range of colors and dynamics. I really try to explore that.”

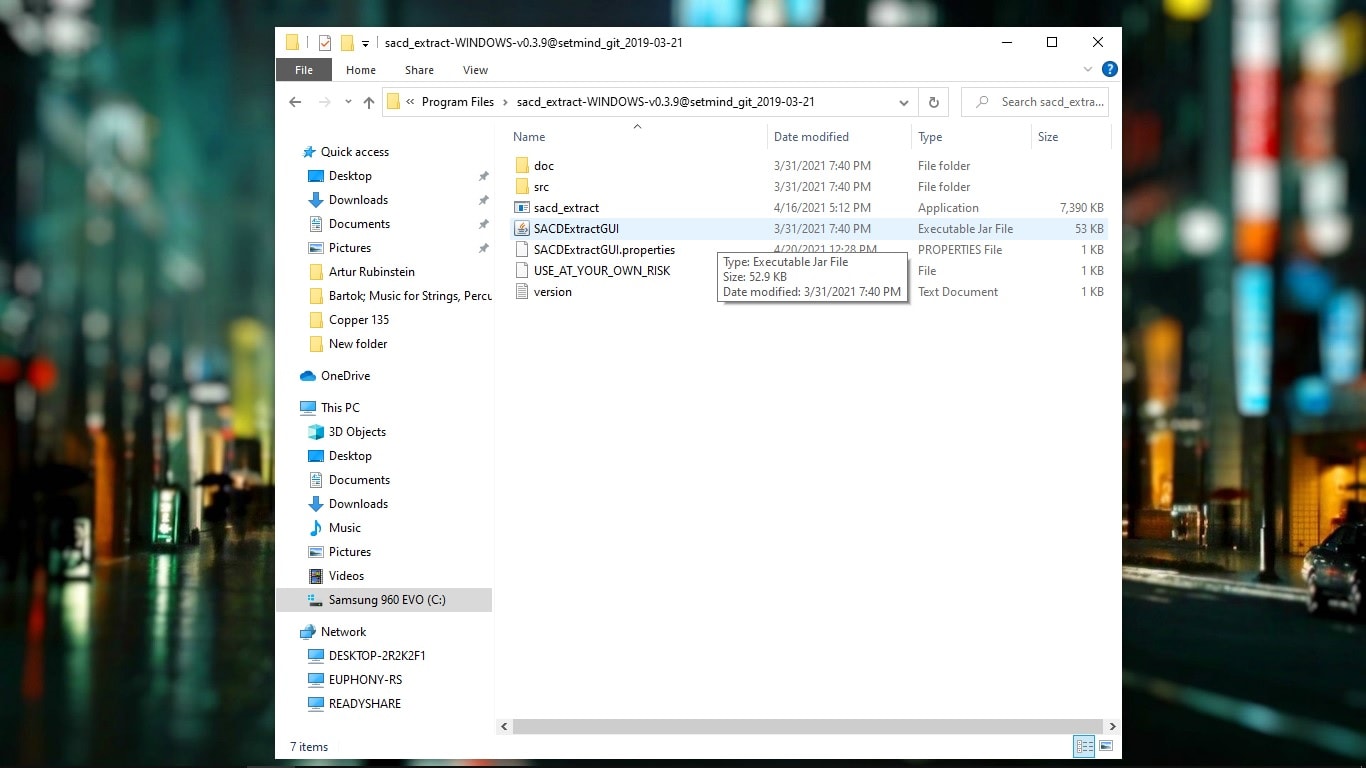

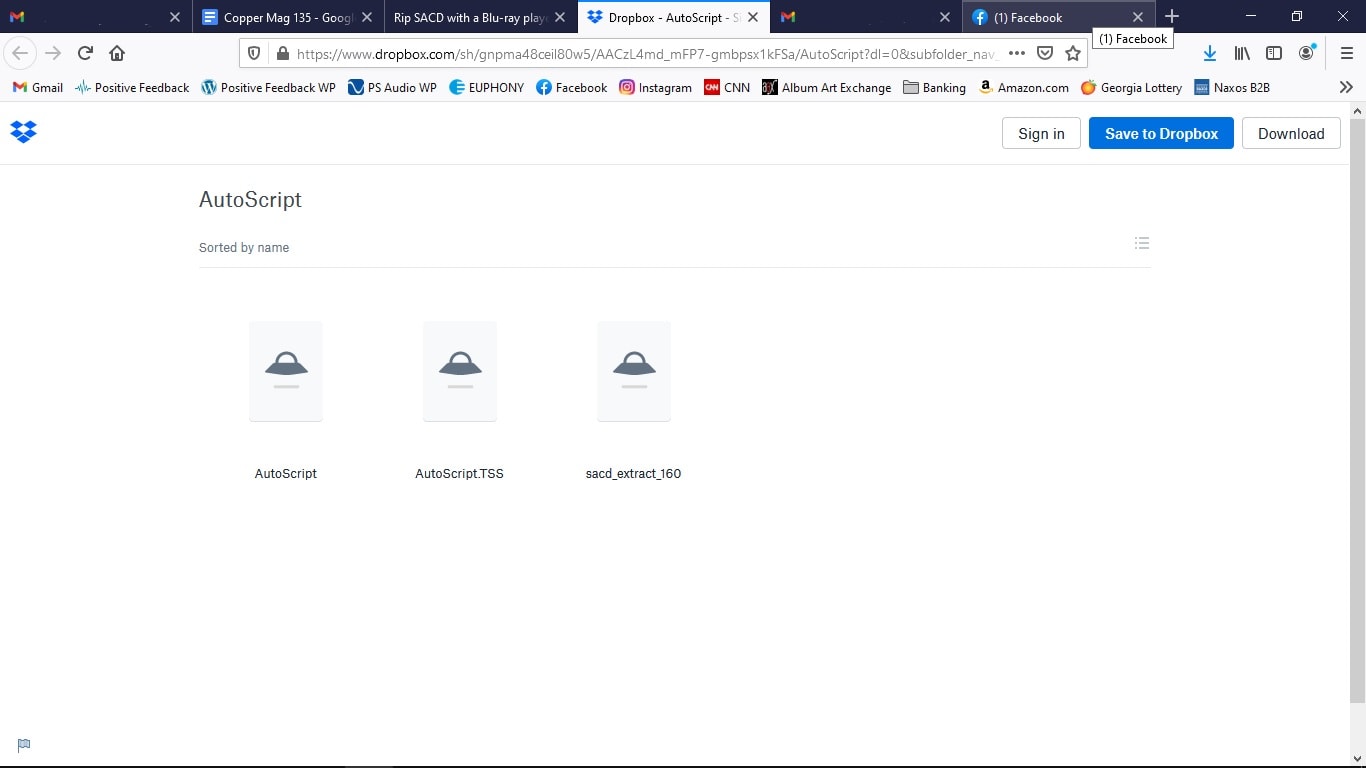

Ana Vidović Live at Hampden Hall presented her with the opportunity to fulfill a lifelong dream. “My wish has always been to do a live recording. And finally, I had a chance to do that, so I’m very happy.” Recorded at Hampden Hall in Englewood, Colorado, all the nuance and expression of her playing were captured using Neumann U67 large-condenser main and close mics, along with a stereo Telefunken mic at a distance for hall ambience. The album was recorded using Octave’s Pure DSD 256 process to convey the highest level of clarity, depth, spaciousness and musical realism.

The double album, available on disc or in two volumes via download, was recorded, mixed and produced by Paul McGowan, with assistance from Jessica Carson and Terri McGowan. It was mastered by Gus Skinas. Ana Vidović Live at Hampden Hall features Octave’s premium gold disc formulation, and the discs are playable on any SACD, CD, DVD, or Blu-ray player. They also have a high-resolution DSD layer that is accessible by using any SACD player or a PS Audio SACD transport. In addition, the master DSD and PCM files are available for purchase and download, including DSD 256, DSD 128, DSD 64, and DSDDirect Mastered 352.8 kHz/24-bit, 176.4 kHz/24-bit, 88.2 kHz/24-bit, and 44.1 kHz/24-bit PCM. (SRP: two disc-set, $58; each volume via download, $19 – $39 depending on format.)

The album begins with a masterwork – a guitar transcription of J.S. Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major. Vidović performs this extremely challenging piece with a spellbinding depth of feeling. Other selections include Bach’s Violin Sonata No. 1, the Gran Sonata Eroica, Op. 150 and Grande Ouverture Op. 61 by Mauro Giuliani, Intro and Variations on a Theme by Mozart, Op. 9 by Fernando Sor, and Augustin Barrios’ magnificent La Catedral, all performed with Vidović’s remarkable virtuosity and connection with the music.

I spoke with Ana about the new album, her approach to guitar playing, and many other things.

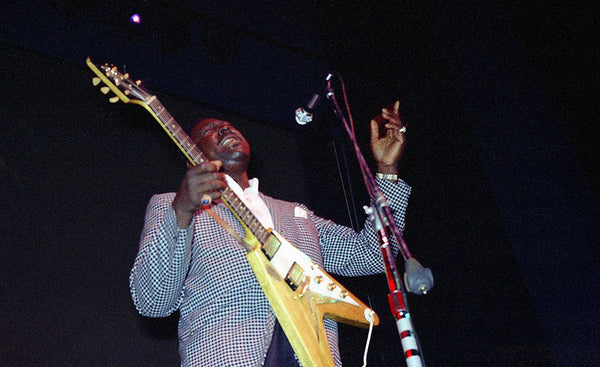

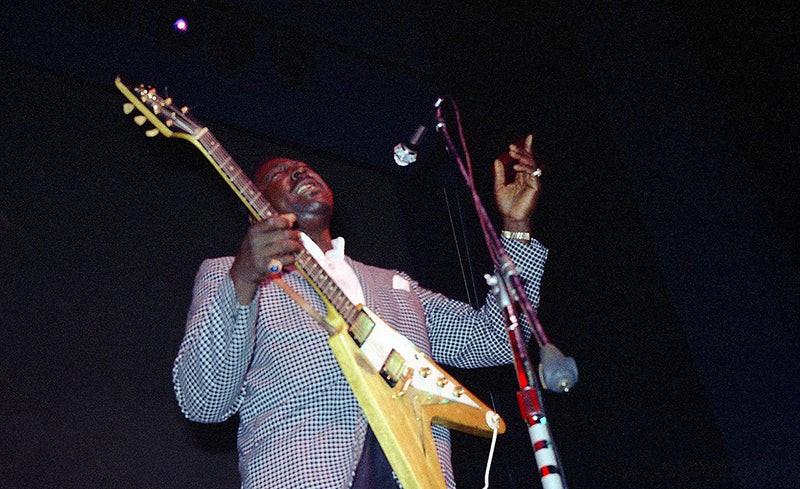

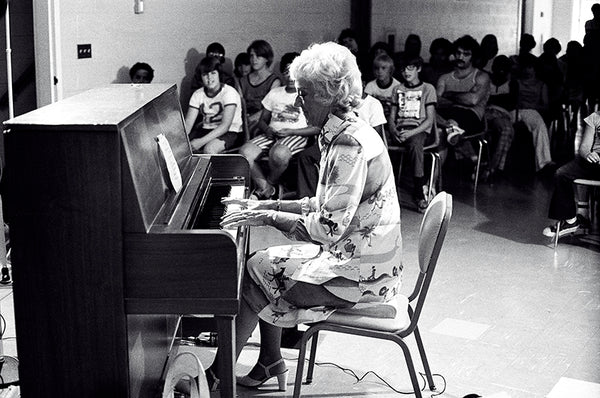

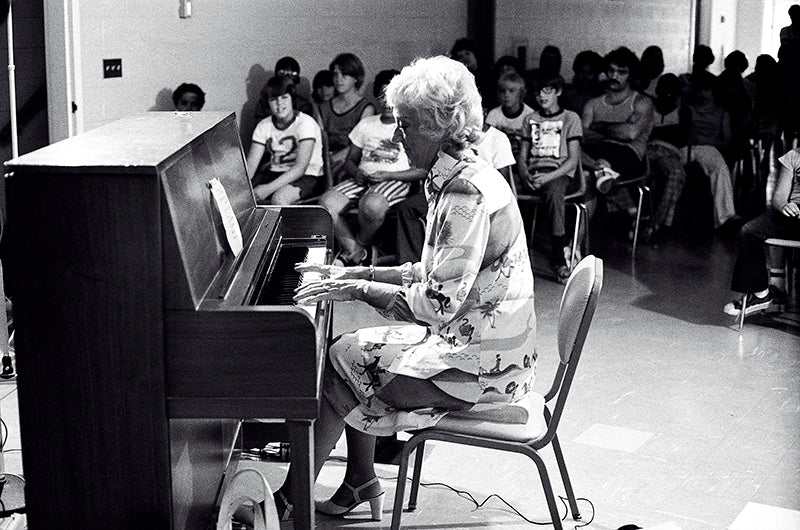

Ana Vidović. Courtesy of anavidovic.com.

Frank Doris: You're a world-class musician. You've been performing since age eight, and you were the youngest student to attend the Academy of Music in Zagreb, Croatia. When did you first realize you were going to be a musician, and what made you pick classical guitar?

Ana Vidović: I was very much influenced by my older brother. I have two older brothers, but one of them is a guitarist. His name is Victor, and he was first from three of us kids to start playing an instrument. So, he chose guitar, I think because of my father. My father used to play electric guitar, bass guitar, was very much active in his youth, and had his own band. He loved all kinds of music; rock, pop, jazz, blues, and classical, of course. Growing up, we had a lot of records: Segovia, Julian Bream, John Williams. He loved classical guitar, but never really played it, [but] Victor picked it up very early. I think he was about seven or eight.

He was an amazing talent, progressed very quickly, and started to go to competitions and started performing [when he was] very young. When I was [about] five years old, he was already in his teenage years. So I listened to the sound of the guitar from a very, very early age, and said, “oh, I want to do that.”

Then he taught me some basics of technique. He was my teacher for two or three years. And when I was about eight, I started to go to music school.

FD: Jumping ahead to your new Octave album Live at Hampden Hall, why did you choose the pieces that you did? There's a wide range of moods and you play an arrangement by Fernando Sor (Intro and Variations on a Theme by Mozart, Op. 9), who is a tremendous influence in classical guitar composition.

AV: That's one of my favorite pieces. All these pieces – when I perform live, the audience is very important to me, and how they respond to certain pieces. Over many years of performing, I've collected quite a few repertoires, and I had the audience in mind, because people tell me, I'd like to hear you record this piece, I'd like to hear you record that piece. So I was thinking of both my audience, and also listeners who maybe don't play classical guitar, but would like to hear a classical guitar being represented in a certain way. And all these pieces really represent the guitar very well.

So it was a mixture of different things. And of course, I love all these pieces. And the repertoire for the guitar is very interesting. There are, like you say, a lot of moods, a lot of different techniques, and a lot of dynamic ranges that you can represent on the guitar.

FD: The Bach Cello Suites are a challenge for anybody. But I was really struck by your playing on La Catedral. I don't know how to describe it, but it's almost like you're coaxing or pulling the sound out of the instrument. It's like it's blooming. I don't know what kind of technique you use or to get the sound and the dynamics. What are your thoughts on that piece and the way you approach playing it? And I suppose in playing in general.

AV: Well, thank you so much. It's very nice to hear your thoughts. I really appreciate that. And this is my goal, to present each piece in a unique way, [to] try to find things that always, always have the instrument in mind and what the instrument can do. I always put that first.

And over the years, of course, we always search for new things. And these pieces I've played for quite a while. Some of them are new, but some of them are older. And as you mature, as a person, as a musician, you change your way of playing certain pieces. I think La Catedral probably sounded different maybe 10 years ago when I played it, or five years ago. You always try to find new things and challenge yourself.

Also, it was a live performance. In a live setting, I think we, as artists, we process things differently because if you're in a studio, you're just taking many takes. And I think it's more about perfection and every sound, every note has to be [perfect]. But in a live setting, you are connecting with the audience. It's a different quality of performing, so maybe that comes out as well. And La Catedral is a beautiful piece.

FD: When you're playing live, you're in the moment and you feed off the energy of the audience. But when you're in the recording studio and you're looking at that red light, it's intimidating.

AV: It's such a different feeling, when you go into the studio and there's nobody there except the sound engineer. My wish was always to do a live recording. And finally, there was a chance to do that. So, I'm very happy.

FD: What did it feel like to hear your music played back with such good sound quality?

AV: When I first heard it, I was really amazed, and I had some of my friends listen to it. I wanted to hear different opinions, and they all just they said “wow, that's really something special.” Paul did a wonderful job. He really captured the moment, also the sound of the guitar, and I think he really had a clear idea how he wanted it to be represented. The guitar can be a challenging instrument to record. So I was just very, very happy and amazed with the quality of his work. And he was very respectful. He let me listen to it many times. I really enjoyed working with him and just capturing the moment.

FD: What kind of guitar do you play? It has a sweet, rich tone, and being a guitar player, I’m really interested in that sort of thing!

AV: The quality of the art of guitar making is on such a high level, and many people are very innovative and trying to do new things. This guitar was made by an Australian maker, Jim Redgate. I met him more than 10 years ago, because I was looking for an instrument…the most important thing for me personally is to connect with the instrument. When you play, you have to have this connection. You have to feel like it's part of you. Of course, I was looking for a certain sound, a certain projection, a certain volume. But the most important thing was just to feel like this is something that I could be playing for many, many years.

FD: I'm with you there.

AV: You know what I mean?

FD: I feel the same way. You could go to a store and play five or 10, and you're like, “no, no, nah.” And then you pick up the one where it's just, “wow. I have to have this one. I can't leave without it.”

AV: There is always that one, right…mine was kind of the same situation. And after that, I never changed. I love it. I really do. And this particular one keeps opening up as you play it, as you kind of grow with it; it's still changing, so there's so much to discover still.

FD: Wow. After all this time.

AV: Yeah, yeah, exactly. Amazing. They change, and I think it's also due to us, the way we play, and they're kind of changing with us. So it's kind of both the player and the instrument. [Ana uses D’Addario strings – Ed.]

FD: Who were your biggest musical influences? You already mentioned your brother, but who are some other people who have affected you as a musician?

AV: Many artists from different backgrounds. I always really was curious about other styles of music. Of course, I play classical as my first, but I always was really, really curious about jazz, blues, rock, pop, anything, just anything that's good-quality music. Of course, I listen to classical, but these days I find myself listening more to jazz and blues because these musicians really inspire me. They approach music in a different way, so I’ve learned so much from them. It's something that I can apply to what I do [it would be difficult to name them all]. B.B. King, Sting, I love the Police, Stevie Ray Vaughan, just a variety of different genres. And I always find something that I can learn from these artists.

FD: I was listening to Charlie Christian the other day, and in his time, it was groundbreaking. There were acoustic guitarists who had gone before him, but he was really one of the first electric guitar players to play in that jazz soloing style. Or, say, Wes Montgomery. This is coming from another world, what he's playing.

AV: Yeah, exactly. When you hear it, you just kind of know, it's them, right? It's their sound, and they're so unique in what they do, but it's incredible because we don't know where it's coming from. It's like [from] a different planet, different world.

FD: Sometimes I wonder if even they know where it’s coming from.

AV: That's a good question! And I think in a pure way, I think in some of these artists, it's so pure because they're not trying to…they're just doing what they feel from inside, and that's the best. They're just doing. Of course, they work hard, but I think there is a certain level of talent that they developed. But you're right. Yeah, it's incredible.

FD: That leads me to a question: playing a classical guitar piece requires a lot of study and preparation. How do you prepare for a piece?

AV: Well, the preparation is a very long process, to come to the point where you are ready to perform something live and record it. I would never record something or perform live if I wasn't a hundred percent ready. So all the preparation, the work comes before you step on stage and before you have the confidence to play something in front of the audience. Some of these pieces [on the album], are older, some are new.

To prepare one piece, for example, the Bach Cello Suites, it's like different steps that we take. It's first learning the notes, [the] music, working on the technical aspect of that, takes the most time because you have to work on the fingerings, you have to work on the finger placements. On guitar, you can play a certain line or a certain note in many different places. So you have to decide where to play it, and how to play it with what dynamics, and how much pressure you use with your fingers. All these decisions have to be made very early on, and that's part of the process.

And after that, when you feel comfortable with that part [of the process], then you work on the performance dynamics and the colors. That's a next step, which also takes a lot of time. The last is the memorization. We usually play without music, without the score. That takes also a lot of time to be ready to perform live. The memory has to be very solid. It has to be, [that] if something happens, you can find your way around. You have to know what's coming up, what note is coming up. That's the last step usually. And then you kind of mature with the piece, and then when you're ready, to perform it live. I would say [it takes] sometimes months, sometimes years.

FD: I just assumed you had the music in front of you. Wow! I have to tip my hat.

AV: I think if you have music in front [of you], it changes your performance because maybe you’re too much focused on the music score and not so much [on the performing]. I think when you memorize something, it's just a different level. You can just focus on playing, and the sound. I like it better than having music in front of me.

FD: I see more and more and more performers using their iPads. And it's one thing if you just glance at it every now and then to remember a lyric or something. But it's another thing if you just stare at the thing, and it takes away from the performance. I tell players, once you get on a stage, you're not just a musician anymore, you are a performer.

AV: Exactly. Exactly. You have to think about the audience, right? I mean, they're such a big part of the performance.

FD: I have a few more questions. You know the famous Andres Segovia quote where he declared the electric guitar to be an abomination. When I was a kid playing electric guitar, I was like, “who's this guy?” Then I found out he was one of the greatest guitar players in the world and thought, OK, his opinion has some weight! But I guess you don't feel that the electric guitar is something awful.

AV: No. Maybe it's my father's influence, but I’ve always felt like we can really learn so much from other styles. Guitar is incredible because it has so many different styles. I think the guitar is the only instrument [that] has so many different varieties. Look at flamenco [for example]. And all these techniques are so different. But perhaps at the time [Segovia said what he did], it was a different time. I mean, Segovia was amazing. He was the first classical guitarist ever to really bring classical guitar to a certain level. So, I have such an admiration for him. It's incredible what he has done for the instrument. But today, again, we live in a different time, so it's good, too. It's good to be influenced by other artists.

FD: Do you do strictly classical fingerpicking, or do you ever pick up an electric and play with a pick for fun?

AV: I do. I love it. I wish sometimes that's what I would do [professionally]. That's what I could have done from the beginning. Sometimes you always wish you could do something different, but [electric guitar is] very different. If I were to perform [on electric], I would have to completely, completely focus on that. Because as I said, those are different styles, and it's amazing how everything is different, the technique, the way you hold the guitar and the way you place your fingers. Also, the amount of sound that comes out! I wish classical guitar could be louder, but sometimes we use amplification to amplify the sound.

FD: That's what hooked me, the sound of it, the look of the electric guitar. You could be cool in high school. I think that's what got a lot of people interested. And then they figured, “oh yeah, wait, I have to make music with this thing!”

AV: Right? Yeah. And also, all these amazing artists that we talked about, they were a big influence. When you see somebody perform, you say, “oh, I wish I could do that.”

FD: Well, as you say, the guitar is so diverse that maybe you have to focus on one particular aspect of it. Is there anybody who can play anything? Maybe Tommy Emmanuel?

AV: I think maybe some people like to play both electric and classical. But it's difficult because you kind of have to change your mindset, right? So I think it would be difficult to do both. Yeah.

FD: Are there any current classical guitarists that you like or would recommend that people listen to?

AV: I think many, many now, because classical guitar has gotten to a point where people are playing on a very, very high level. There are many young artists that are coming up and finding their way, and even experimenting with different sounds on the guitar and trying to really develop their own individual style. It's really great to see that classical guitar is developing so much. And I always like to see people coming from different parts of the world. When I was living in Croatia, my dream was to go to the United States and study. And everybody has a dream that they develop. That's wonderful to see. And of course, I'm always loyal to the artists that we mentioned, Segovia, Julian Bream, and John Williams are one of my biggest influences. An incredible artist. So, I am very loyal to who I grew up with and listened to, and I really admire those artists.

FD: What’s it like working with the people at Octave Records?

AV: What I really appreciate about them is that they're just wonderful, kind, and very easy people to work with, very honest. And I appreciate it because sometimes in this business, unfortunately, it's hard to find people that are honest [in what] they want to do. The [Octave people] want to respect the artist, and they want to really connect to you in a certain way and let you do what you want to do. I really appreciate that they let me play the program that I wanted to play. They really had me involved in all the processes and the sound and everything. I really had a very, very good feeling when I met them and worked with them. Hopefully we'll do other projects as well. And as I said, when I heard the final product, I was very, very happy because the quality was amazing. And that's what we all want, just to be true to what you do.