We’ve spent a fair amount of time and pixels on the brand Fairchild (part 1 in issue #75, part 2 in issue #76, part 3 in issue #77, and a sidebar/part 4 in issue #82), but there is a lot more yet to be said. Or maybe I’m just obsessive.

Fairchild’s professional products are still highly-regarded and sought-after, 60+ years after their manufacture. Their designs were forward-thinking, and the build quality was what you’d expect from a company that also built airplanes and precision optics. Outside of a few recording studios, they’re seldom seen these days—so when I found a comprehensive piece on a Fairchild pro product, I immediately wanted to add it to this series.

J.I. Agnew is a recording engineer in the U.K., and wizard in all things analog—as you’ll see if you take a look at his website. J.I. undertook the rebuild and voltage conversion of a Fairchild lathe, and has even used it for direct-to-disc recording. What follows is his incredibly detailed account of that process. I think you’ll find it fascinating—but you will need to allow some time to read it! —And oh: the whole “disc” vs. “disk” issue will not be resolved by this article. Just sayin’.

I’m happy to announce that J.I. will soon be writing a column for Copper, beginning with an explanation of the whole mysterious process of how records are made. And now, here’s J.I.’s Fairchild story—Ed.

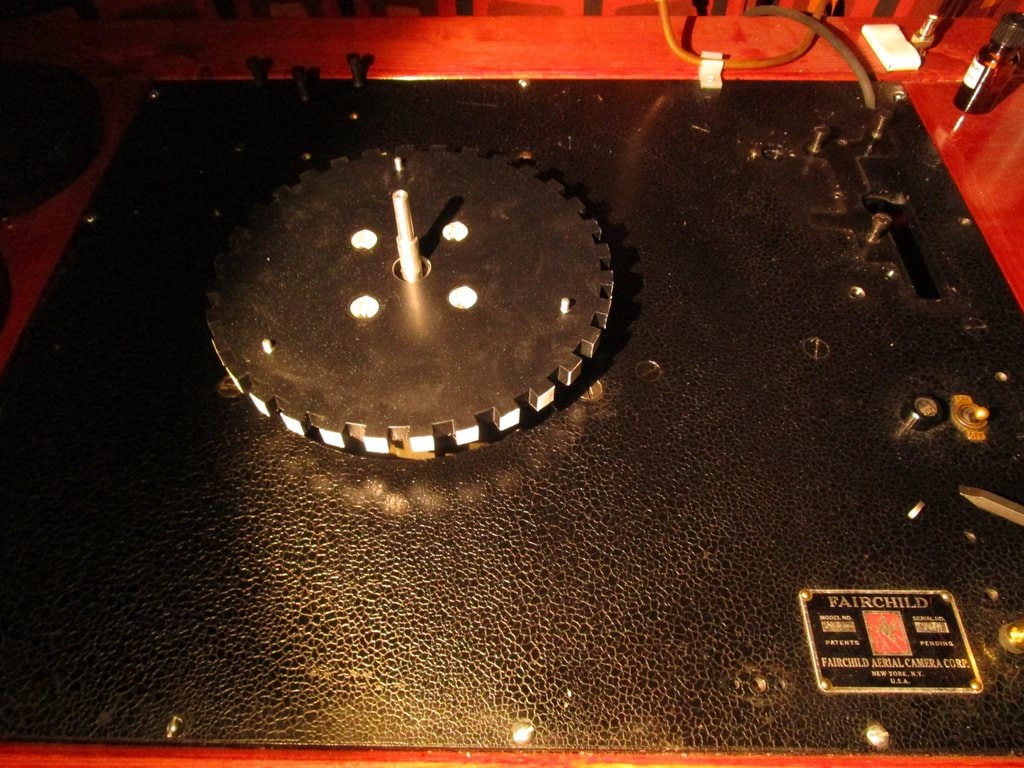

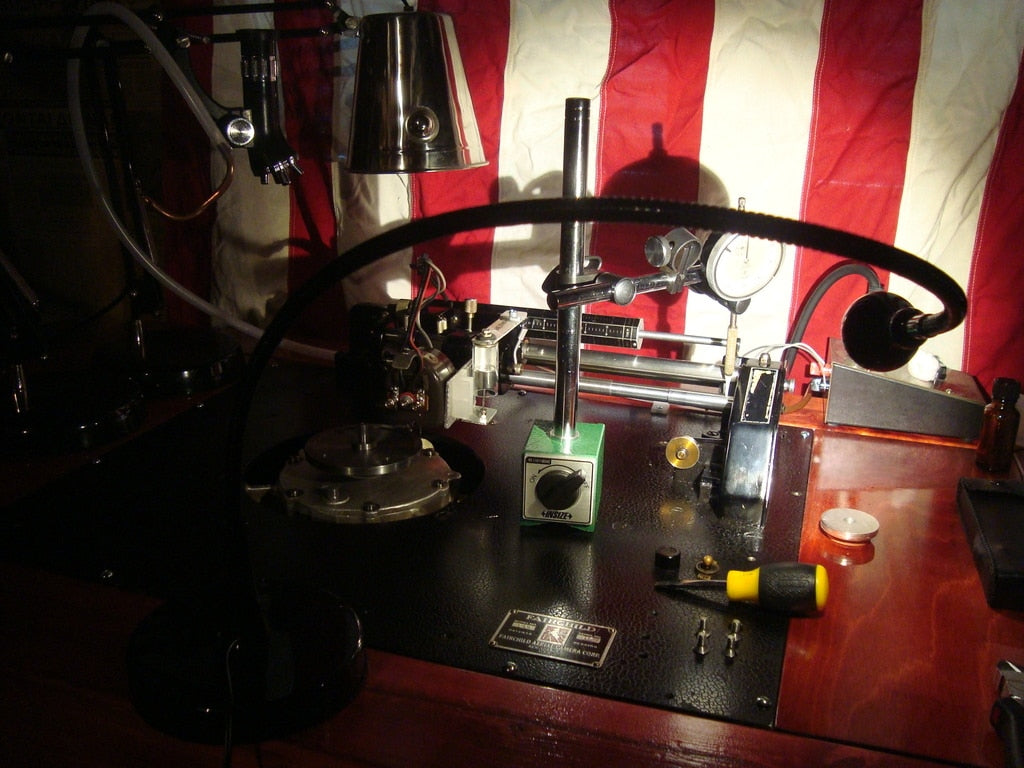

This project started from a bare bones Fairchild Model 199 disk recording lathe, which was found in Florida back in 2015. It was manufactured by the Fairchild Aerial Camera Corporation in the mid-1930’s in New York, before the relevant patents were issued. It was originally sold to a radio broadcasting facility in Grand Rapids, Michigan, where it saw very heavy use, at least until the 1950’s. At some point it was sold to someone in the East Coast again and from there, made it down south.

It arrived in a fairly sad state and it was clear that it was going to need a lot of work, as most old disk recording equipment does nowadays when sold at a bargain price.

It did not come with a cutter head or any electronics and was missing several parts, such as the original cutter head mounting bracket with the advance ball assembly.

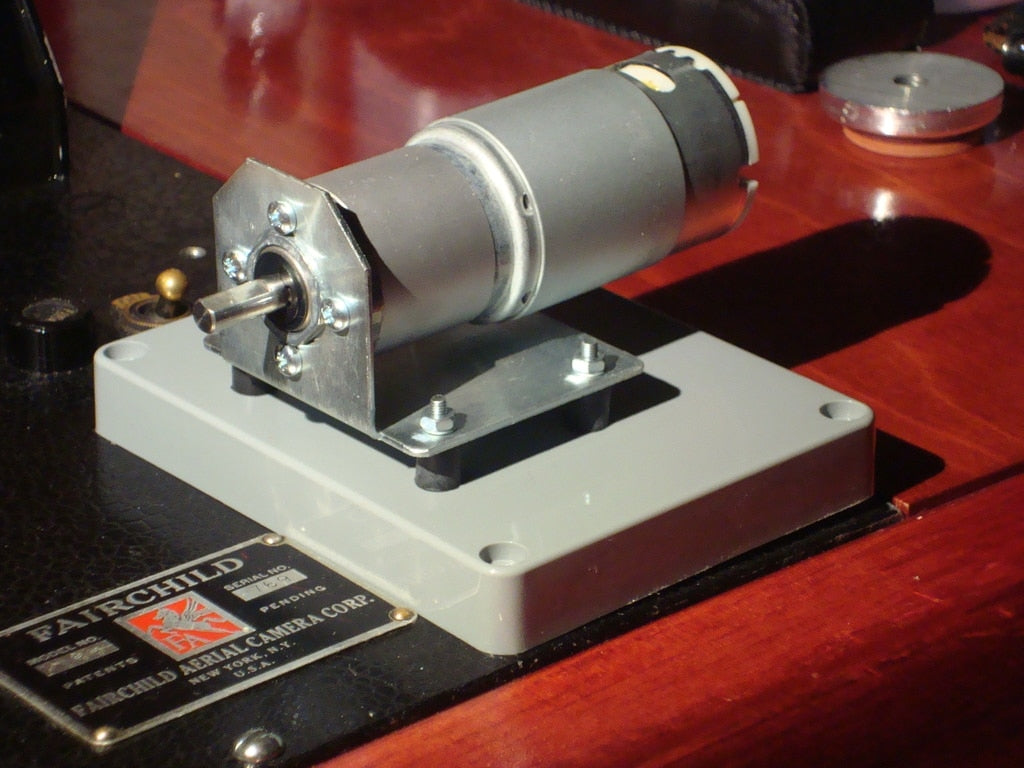

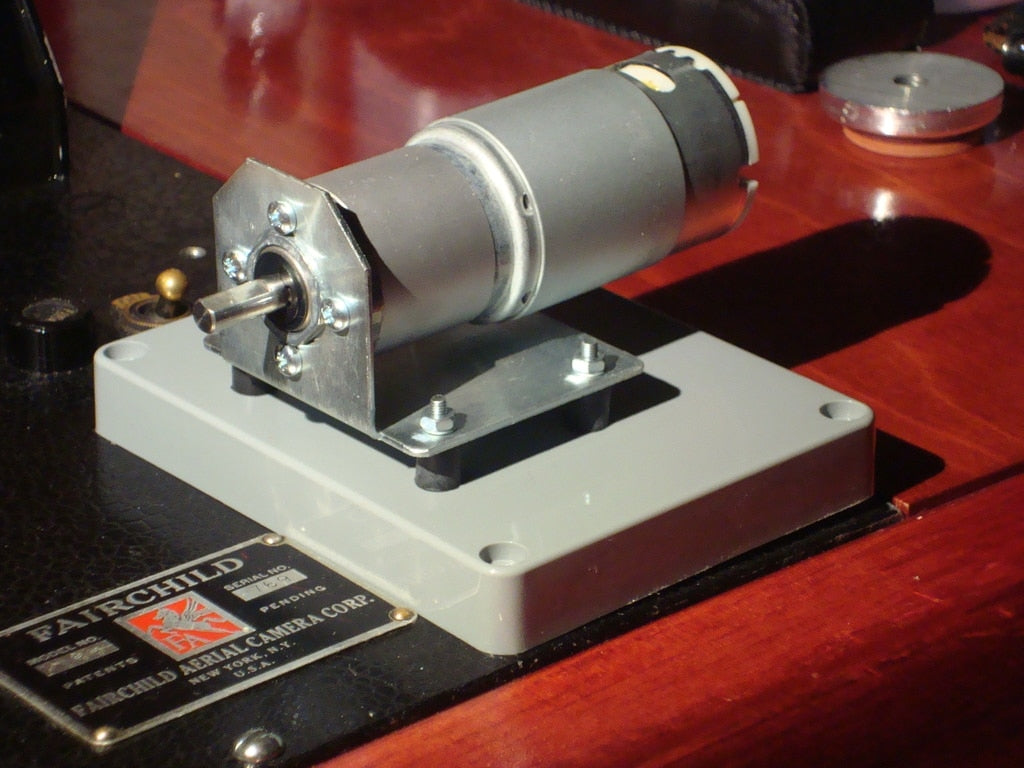

The motor and “drive unit”

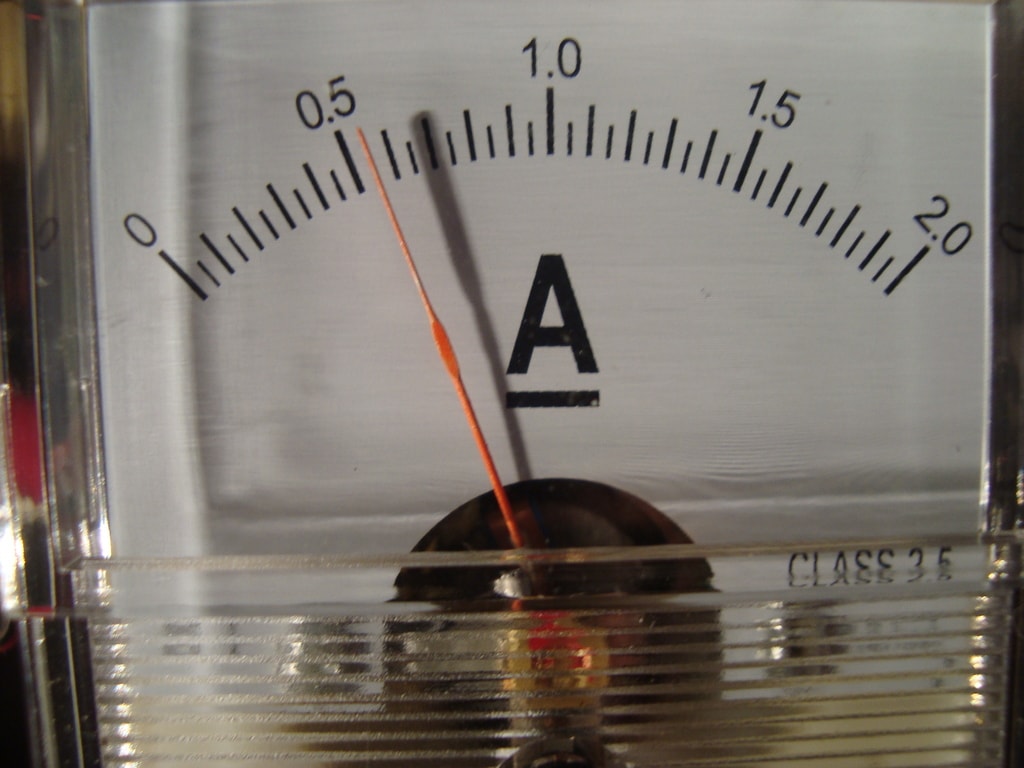

Following a thorough cleaning job and ample lubrication, the next challenge was to make it spin at the right speed. It is driven by a hysteresis synchronous AC motor, whose speed depends on the mains frequency of the supply. The motor and gearbox assembly (Fairchild called it the “drive unit”) were designed to run at the correct speed when powered by 60 Hz mains, but because we are located in Europe (50 Hz mains), it ran slow.

The original manual (available on request) noted that a “50 Hz version” of the “drive unit” was available with different gearing, so it would still spin at the correct speed, even though the motor would run slower. But, it proved impossible to find such a unit. Next thought was to machine new gears of the required ratio. The lathe was operated for half an hour at 50 Hz, and it was found that it ran a bit hot, which was to be expected due to the lower frequency. This would unnecessarily reduce its lifespan, so it was decided to leave the gearbox as is and figure out a stable 60 Hz supply. There are many ways to achieve this at low cost, but none of them are suitable for this application. Since the speed of the platter depends on the line frequency, any instability of the line frequency will result in speed instability. Moreover, any deviation from a pure 60 Hz sine wave (harmonics, noise, etc.) will be causing the motor to run hot and produce excessive vibration.

We developed a dead stable and clean 60 Hz supply unit, specifically for running disk recording lathe motors, the Type 191. Problem solved. We designed and assembled a more appropriate and stable wooden furniture for the lathe, and started the search for a cutter head.

Cutter Head Safari

The search yielded an

RCA MI-4896 monophonic magnetic cutter head of similar vintage.

It also arrived in a very bad, non-functional state. J. I. Agnew promptly took it apart and rebuilt it, making it functional again.

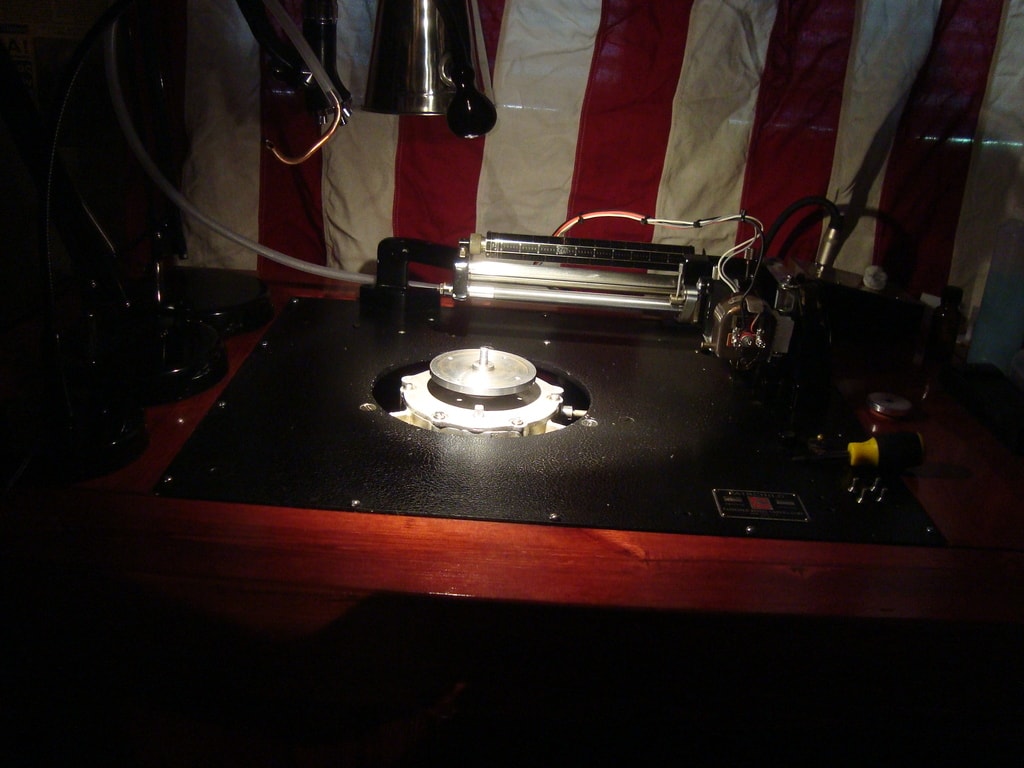

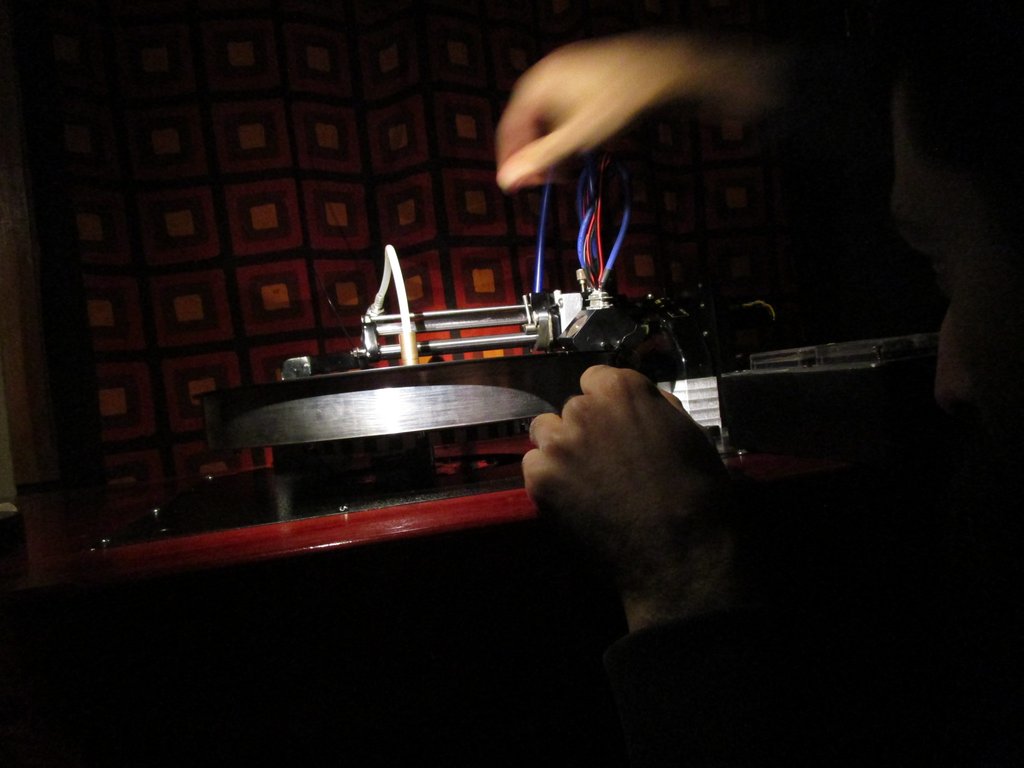

At this stage, we wanted to do a quick and dirty test run of the whole setup, to see where there problems are and to make a plan of action.

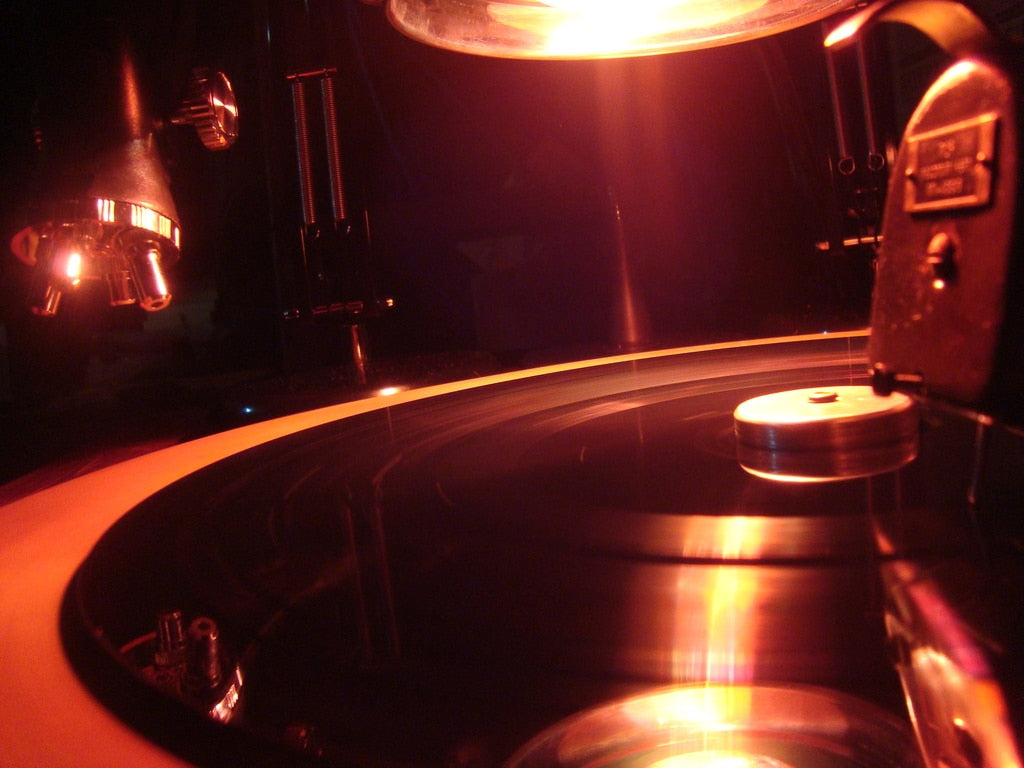

The easiest way to go is embossing/impressing, rather than cutting the grooves on the blank record. This process relies entirely on plastic deformation rather than the removal of material. As such, no suction system is needed to remove the chip, since there is no chip/swarf produced. It does work best warmed up with a heat lamp though, so we put one together. The platter was far from running true and the gearbox was noisy, most likely due to lack of proper lubrication in the past.

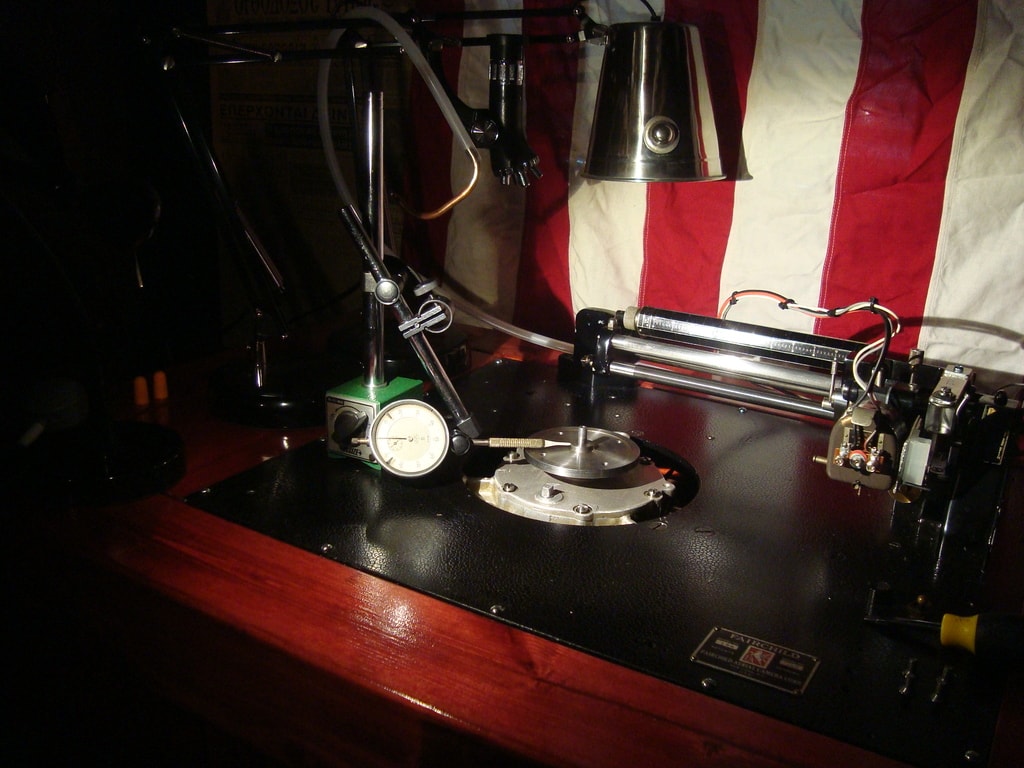

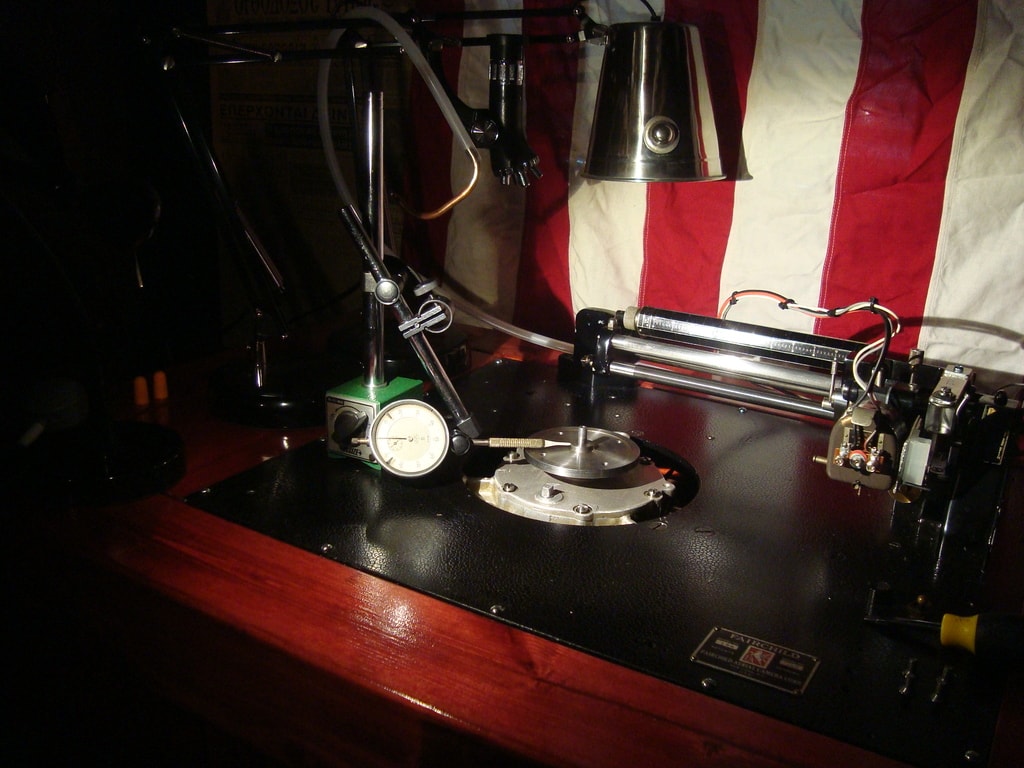

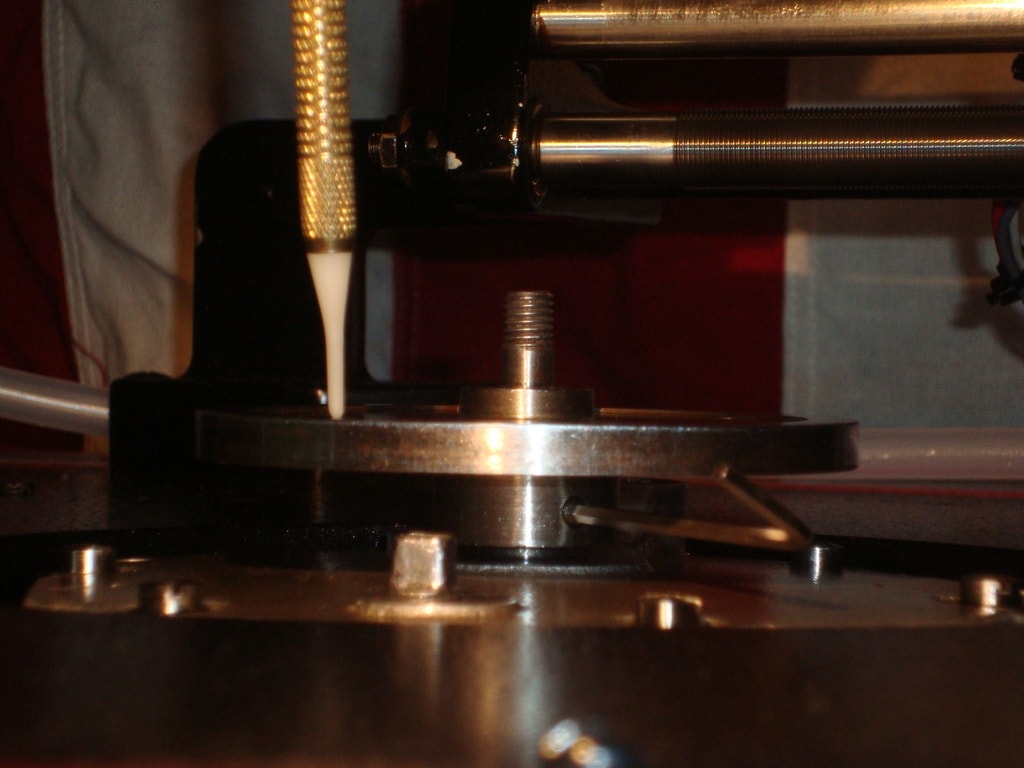

Precise measurements were taken to verify where the problem lies. The platter was not very flat and the mounting method left very little room for adjustment. It had to be modified.

Platter experiments

Height adjusters were installed in the platter to compensate for the lack of flatness. Big improvements, but still far from being as precise as it should be.

Several experiments were then conducted with sandwich-type platter arrangements and a lot was learned in the process about how not to make platters.

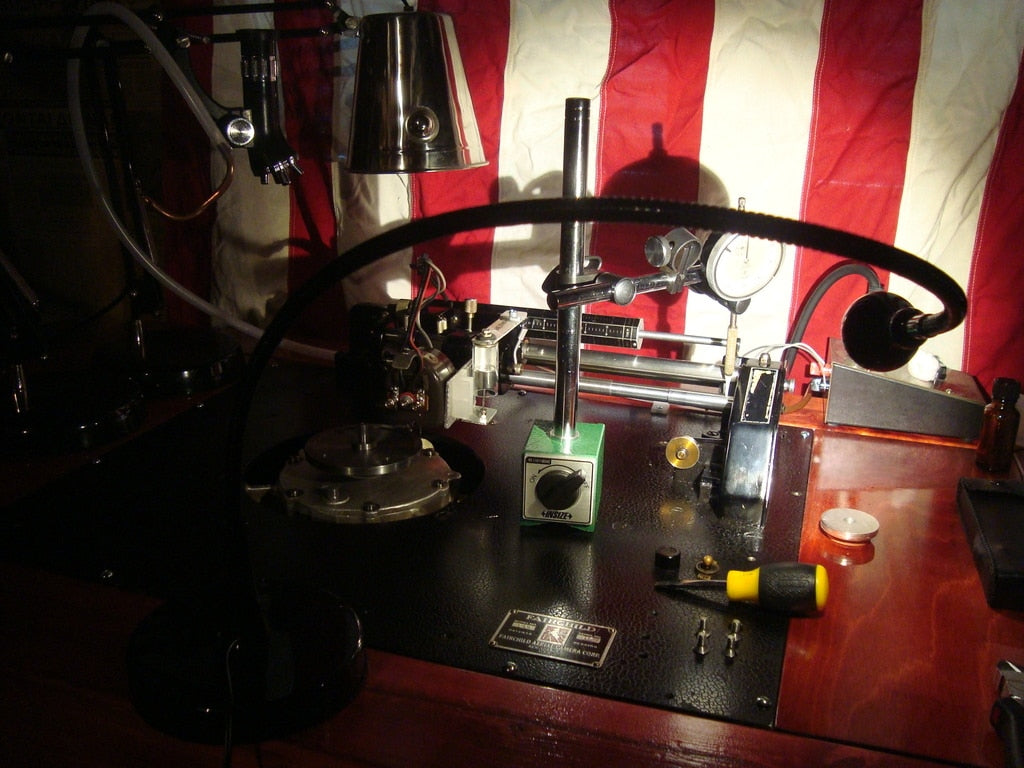

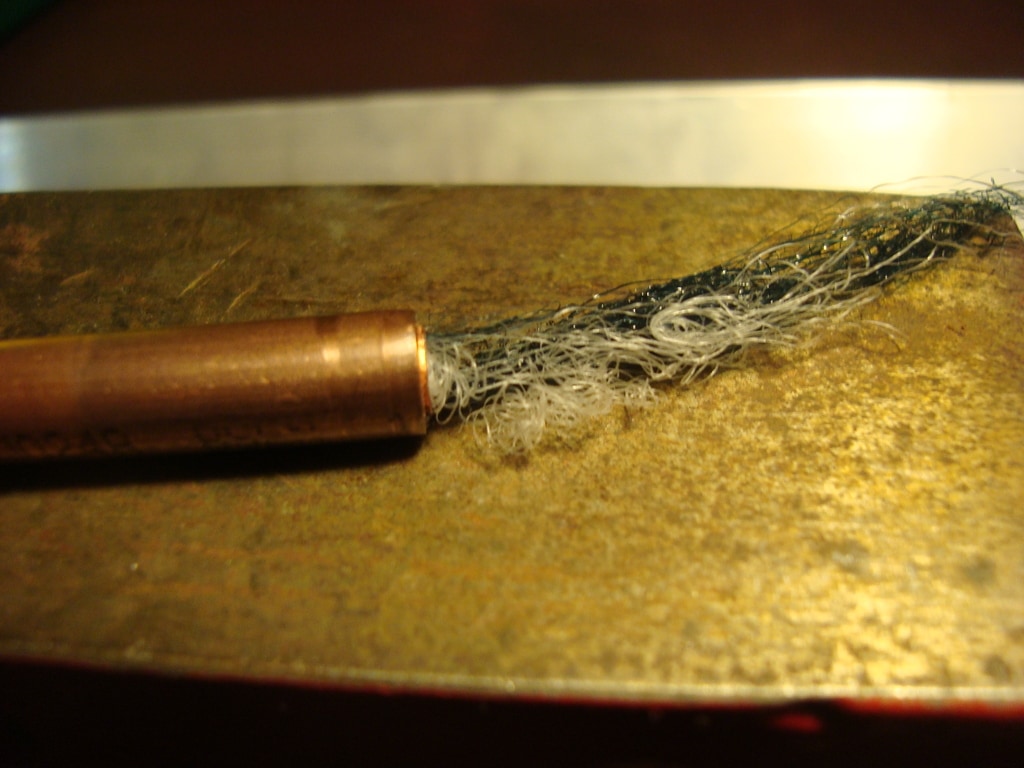

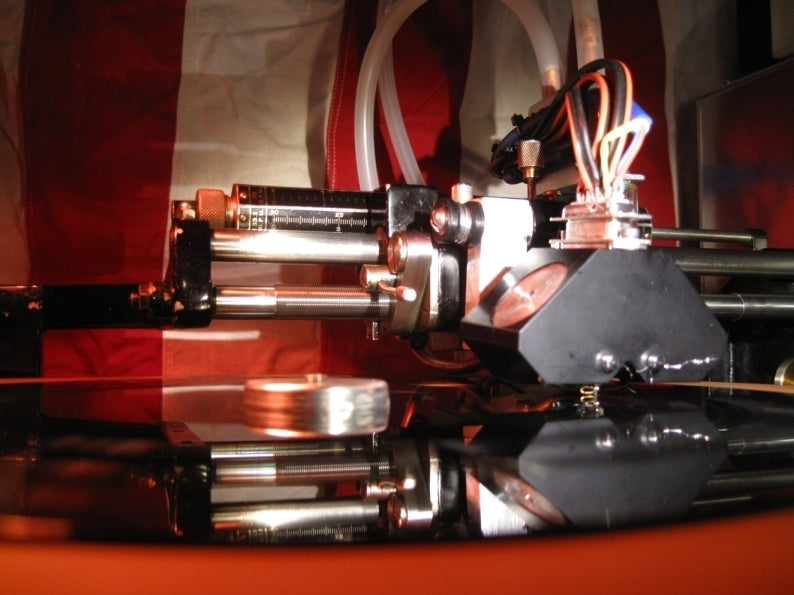

In the meantime, we started putting together a chip suction system to be able to cut some grooves.

In the meantime, we started putting together a chip suction system to be able to cut some grooves.

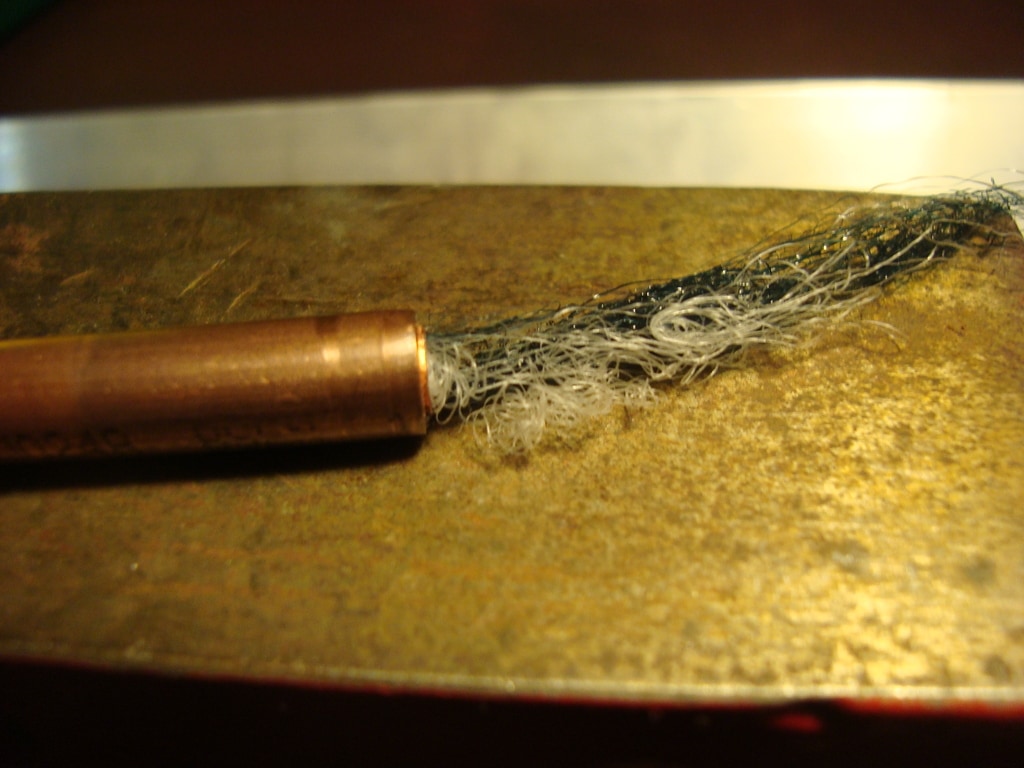

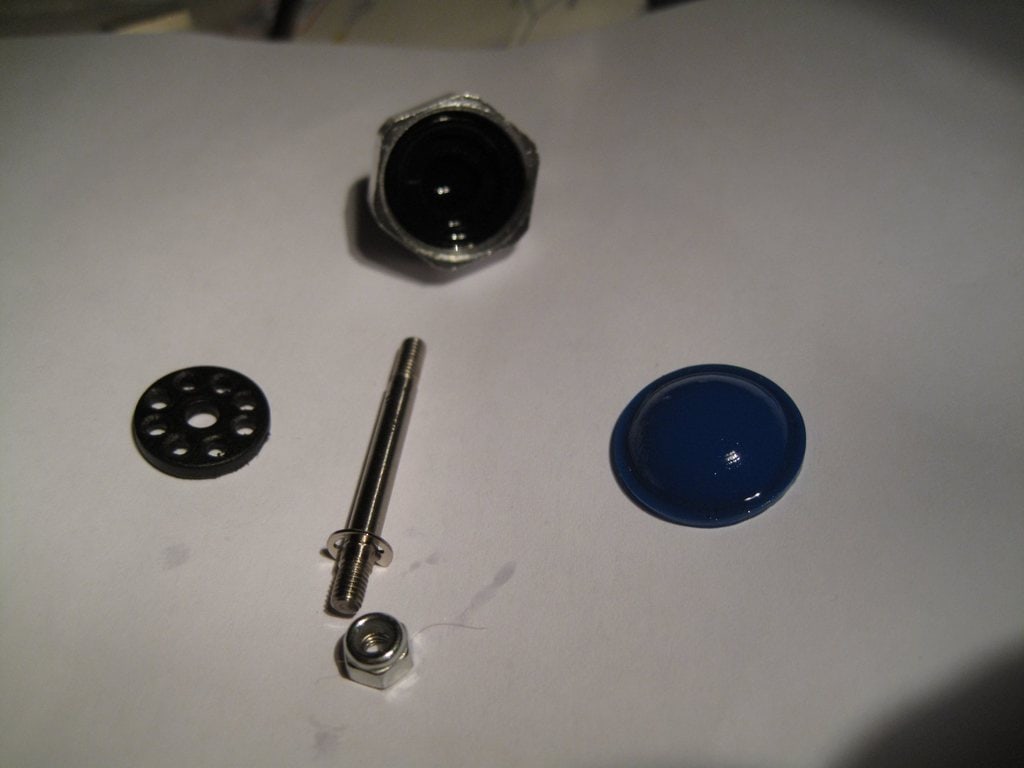

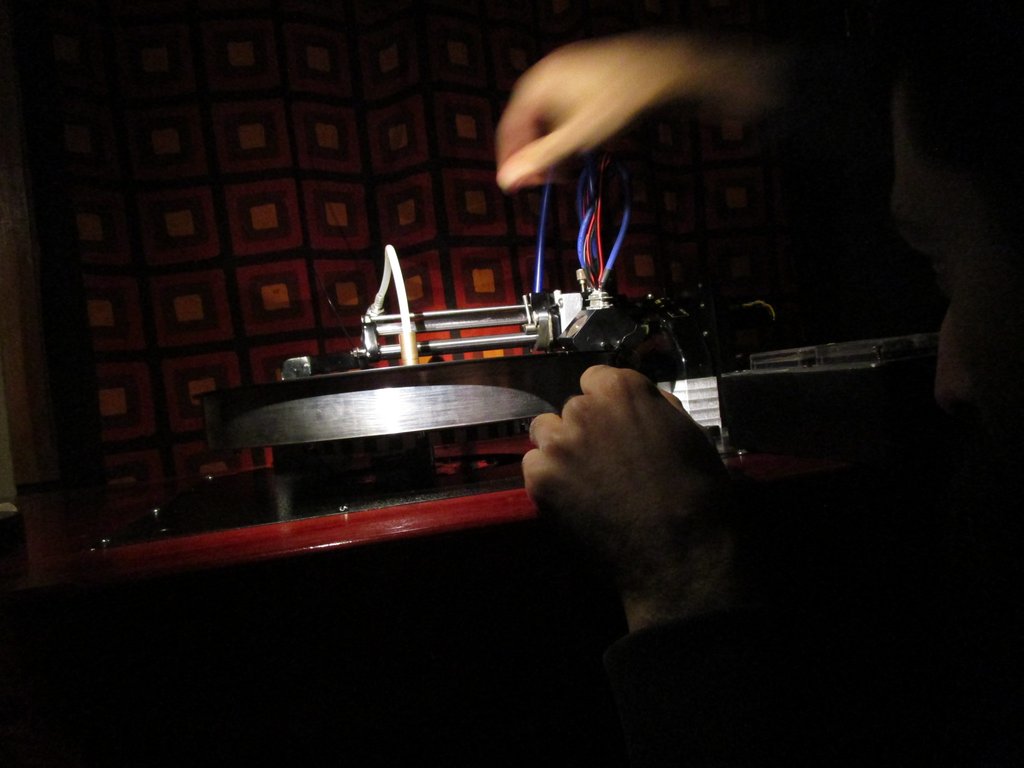

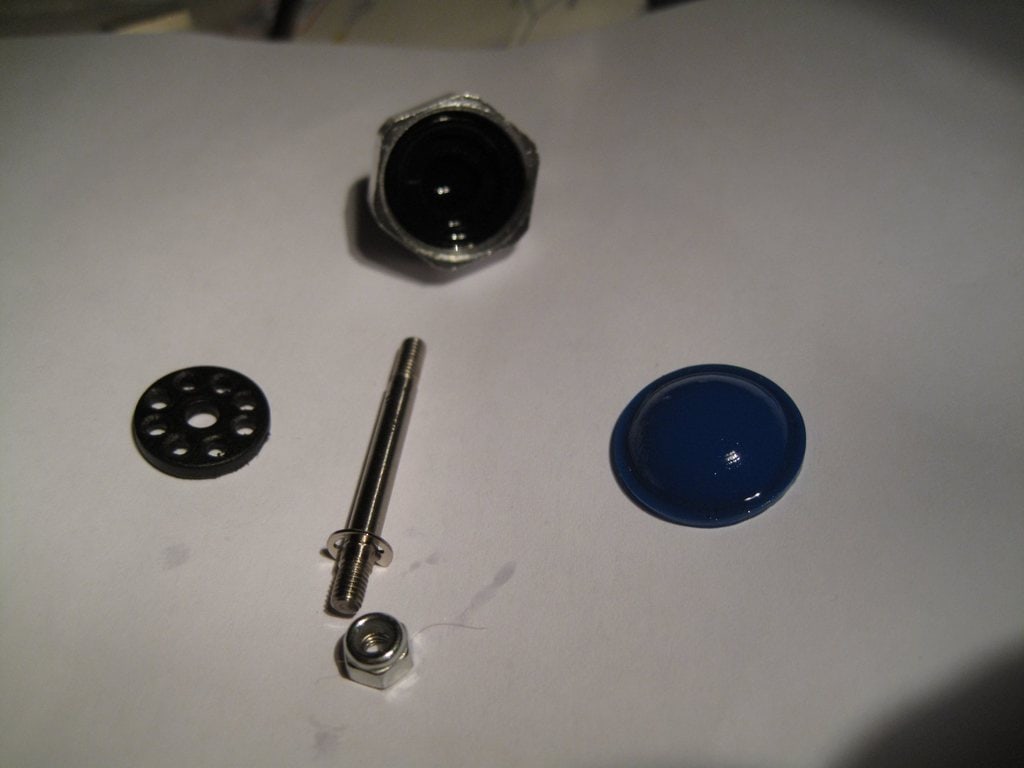

As you can see, the blank disk is being held down by means of a "puck", which screws onto the spindle. This arrangement is far from ideal, but at least a starting point. We started out cutting plastic blanks to get the system set up without wasting lacquer disks in the process. The chip they produce is a transparent-whitish fluff, betraying the sandwich construction of the blanks, which appears to be solid black at first glance.

As you can see, the blank disk is being held down by means of a "puck", which screws onto the spindle. This arrangement is far from ideal, but at least a starting point. We started out cutting plastic blanks to get the system set up without wasting lacquer disks in the process. The chip they produce is a transparent-whitish fluff, betraying the sandwich construction of the blanks, which appears to be solid black at first glance.

The chip suction system needs to be precisely adjusted or it will clog up.

The chip suction system needs to be precisely adjusted or it will clog up.

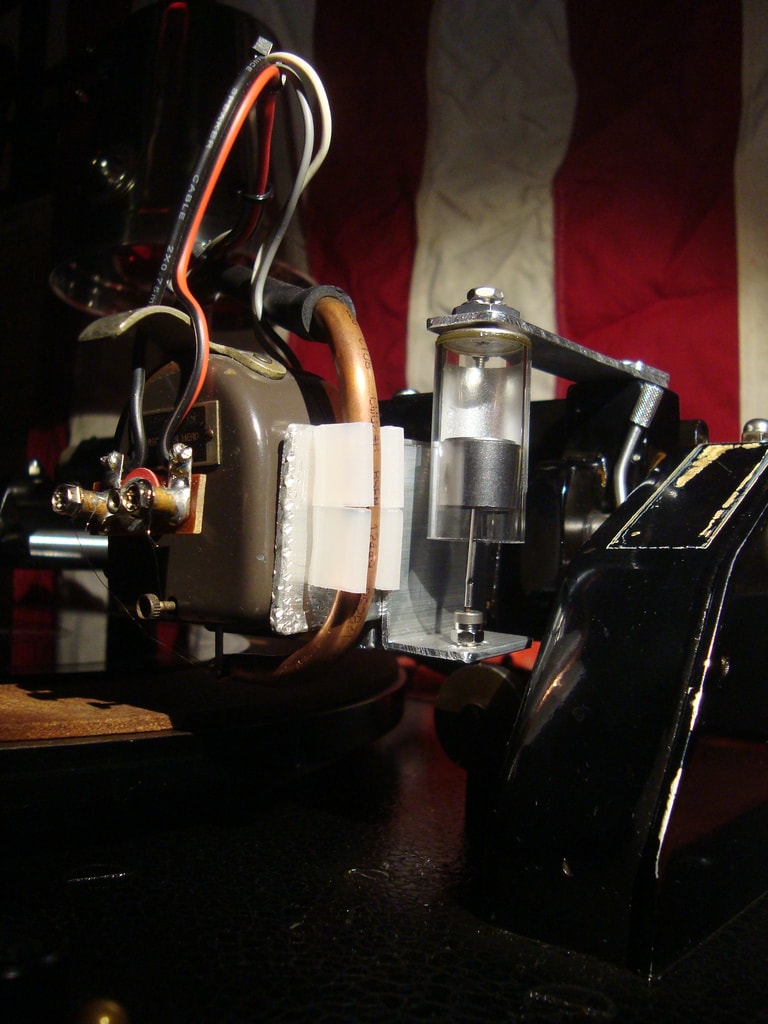

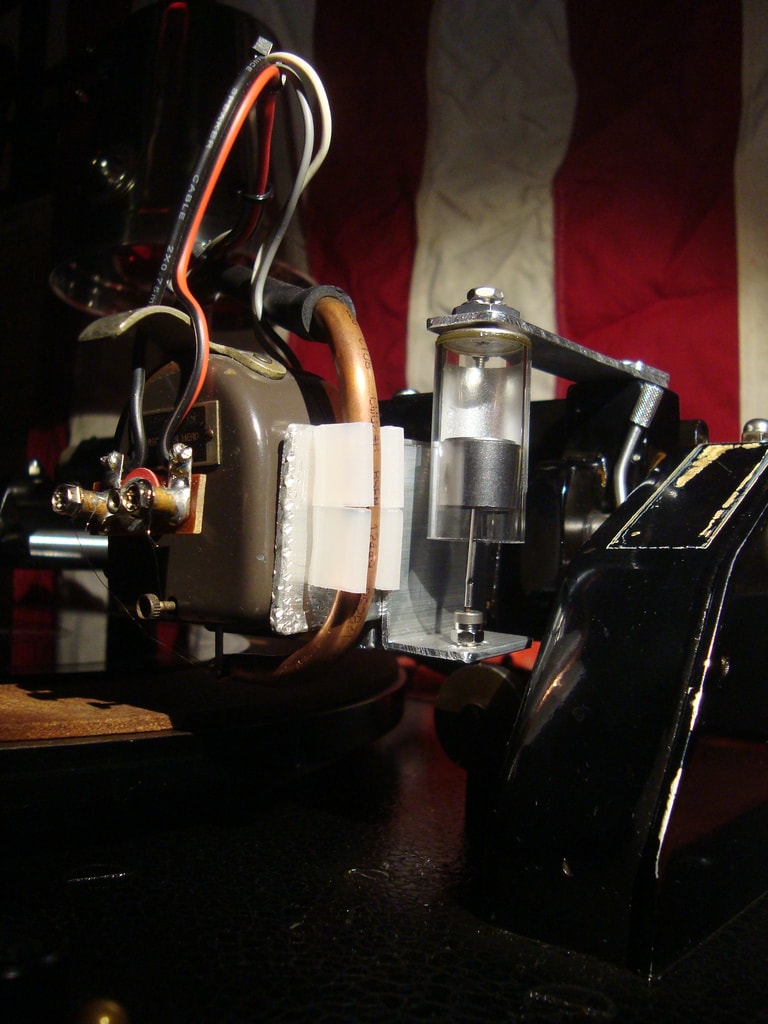

Stylus heating

With this sorted, it was time to try out stylus heating. This should never be attempted before ensuring that the chip suction system is operating reliably. If it fails half-way through the cut, not only is the cut ruined, but the stylus will most likely also end up being ruined. If this should happen with lacquer, it will catch fire so fast, it won’t even be funny.

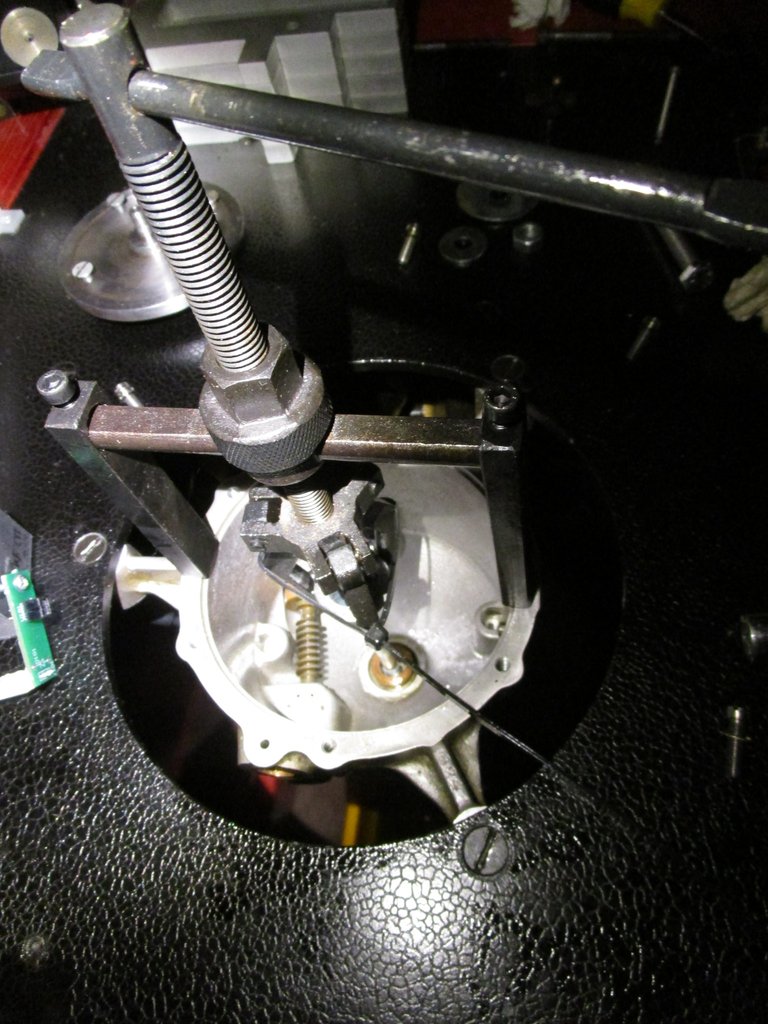

Weird pattern: Vertical oscillations

Next issue was the vertical oscillations (moire pattern on the disk). This is a very usual problem which is easily solved by means of an adjustable dashpot (which we can

supply if required). First we tried an airpot, which sort of worked with the light-weight monophonic head but was not easy to adjust right.

Pitch control system

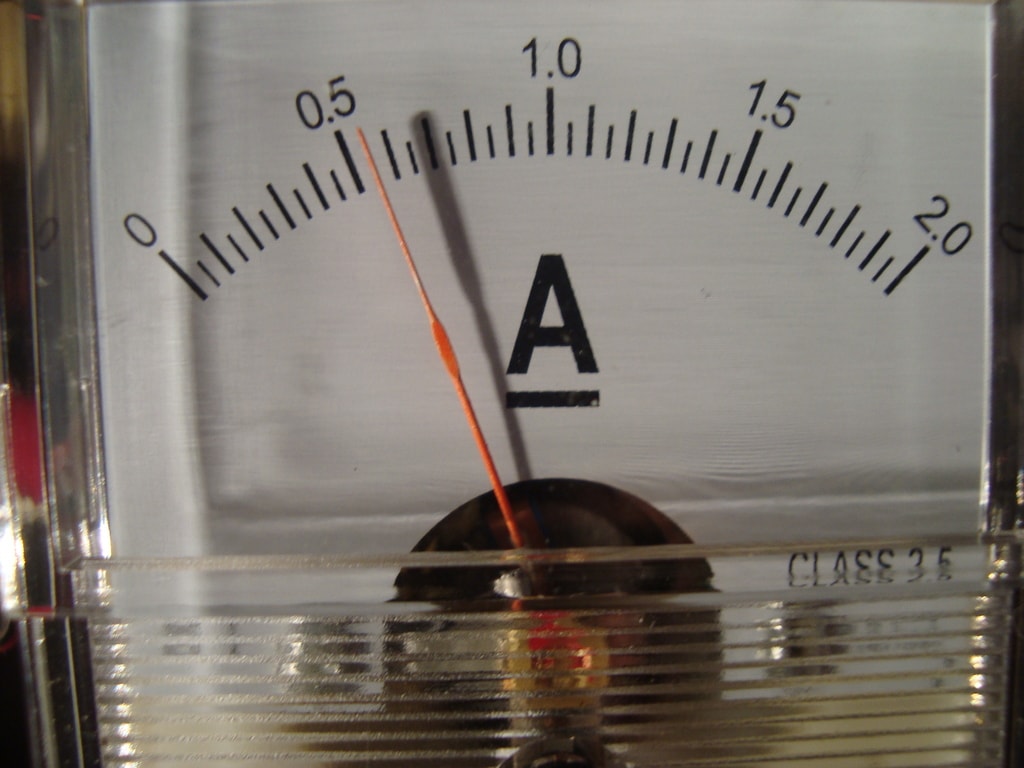

Then the focus shifted to a more versatile pitch control system,

electronically variable, to be able to upgrade to an

automatically variable pitch system in the future when the rest of the issues are dealt with.

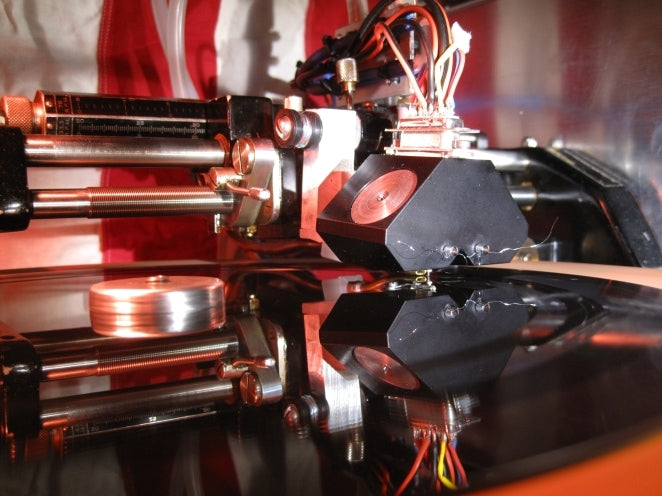

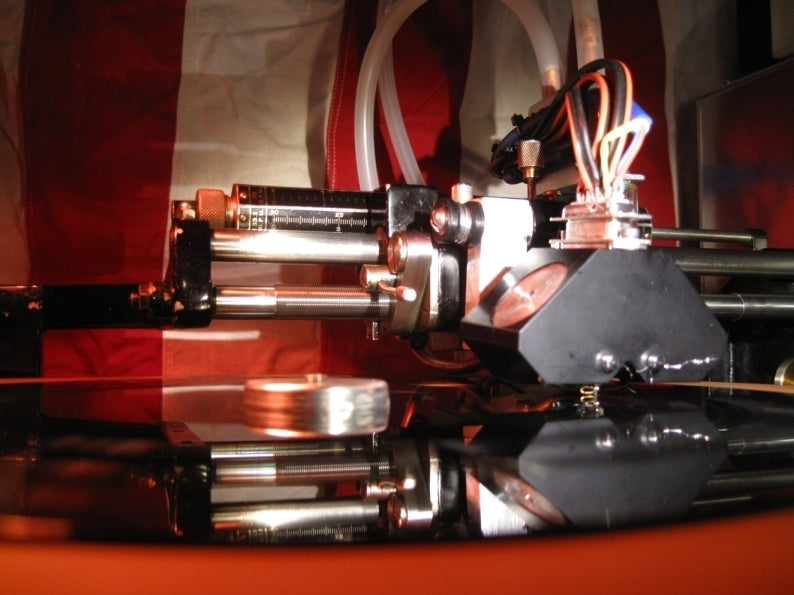

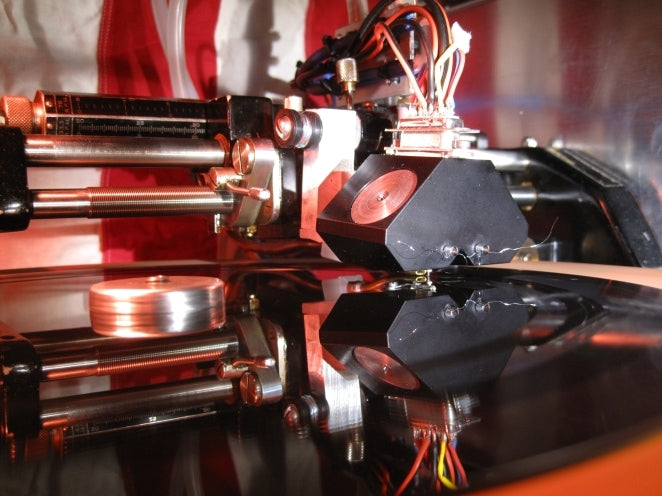

Upgrade to stereophonic cutter head

The time was finally ripe to upgrade to a stereophonic feedback cutter head, the

Caruso Nr. 135! A new head mount was needed, so we designed and built it (we can supply custom cutter head mounts to fit almost any head to any lathe, just

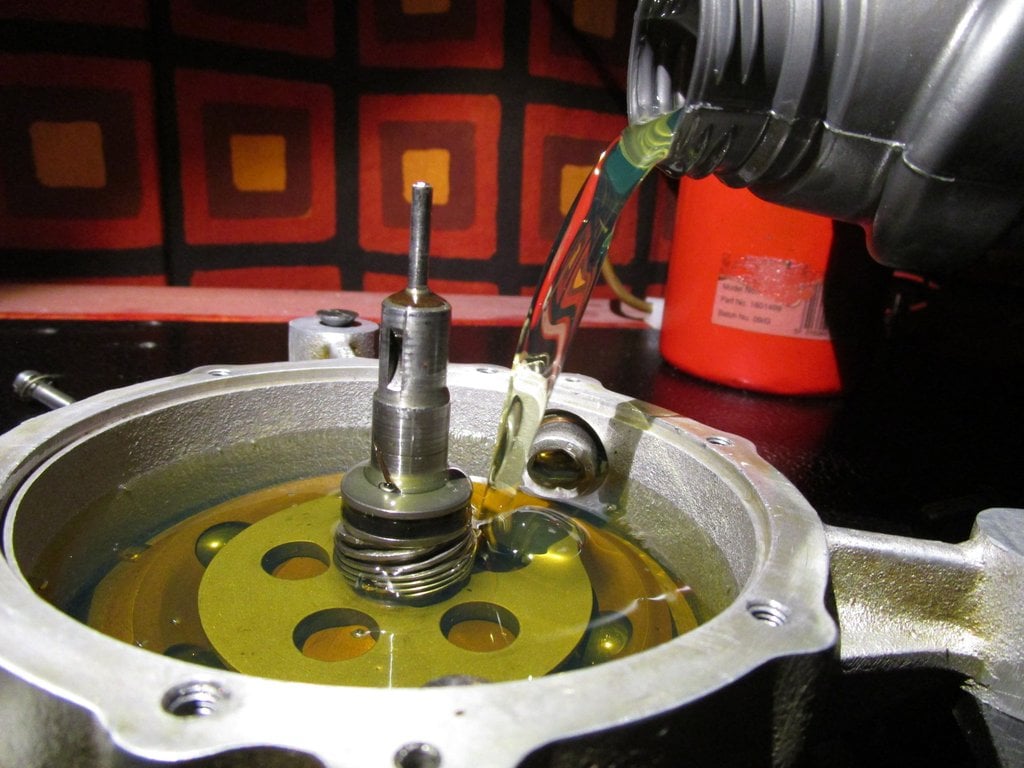

ask). The airpot was not adequate for the much heavier

Caruso head, so we had to upgrade to an oil dashpot as well.

A stereophonic feedback cutter head of course also needs a serious amount of electronics and a different chip suction arrangement. The need for a high performance cutting amplifier system and the lack of any commercially available products at the time, resulted in the development of the Type 891, described in detail in

a paper published in the November 2018 issue of the

Journal of the Audio Engineering Society (JAES).

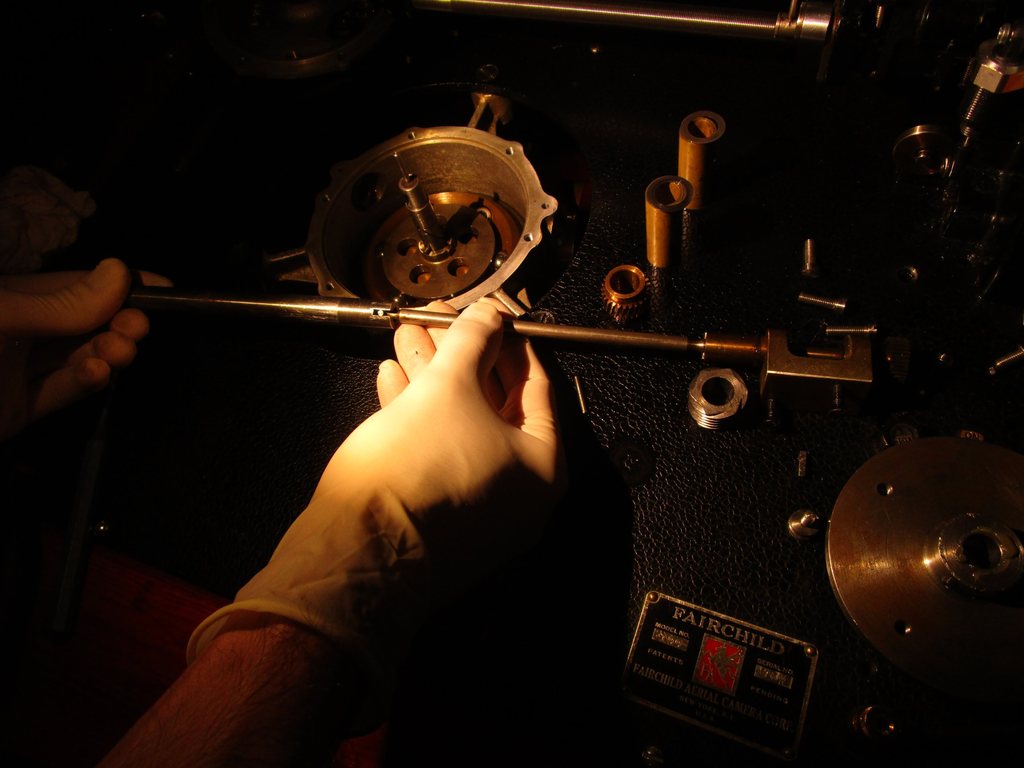

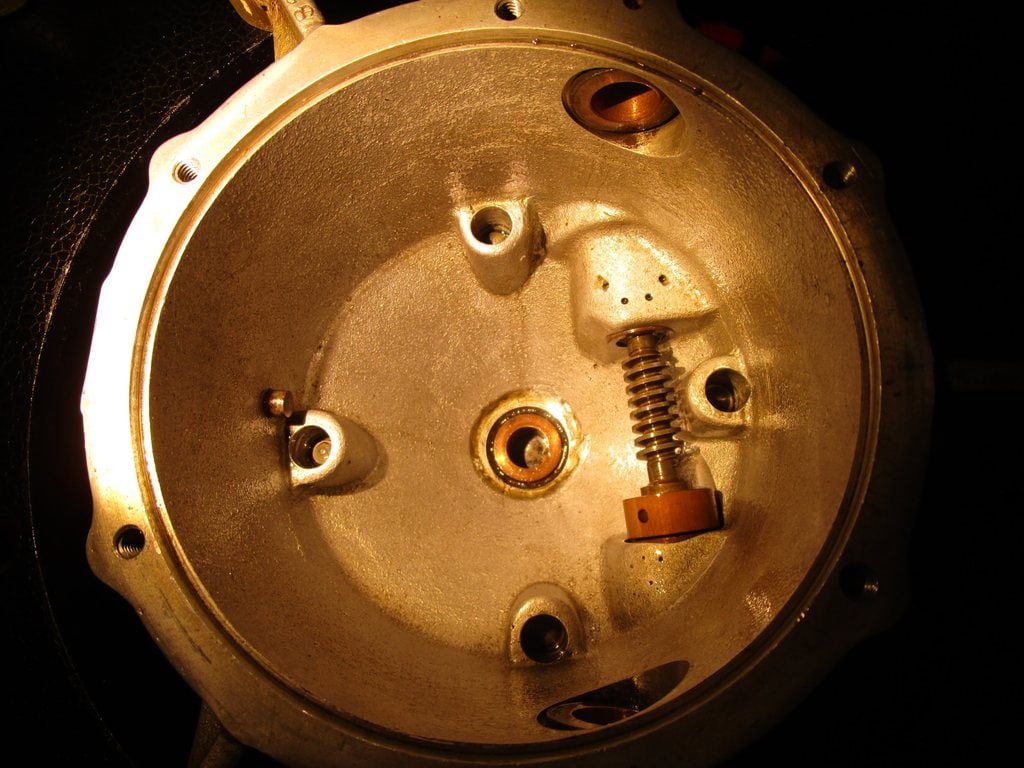

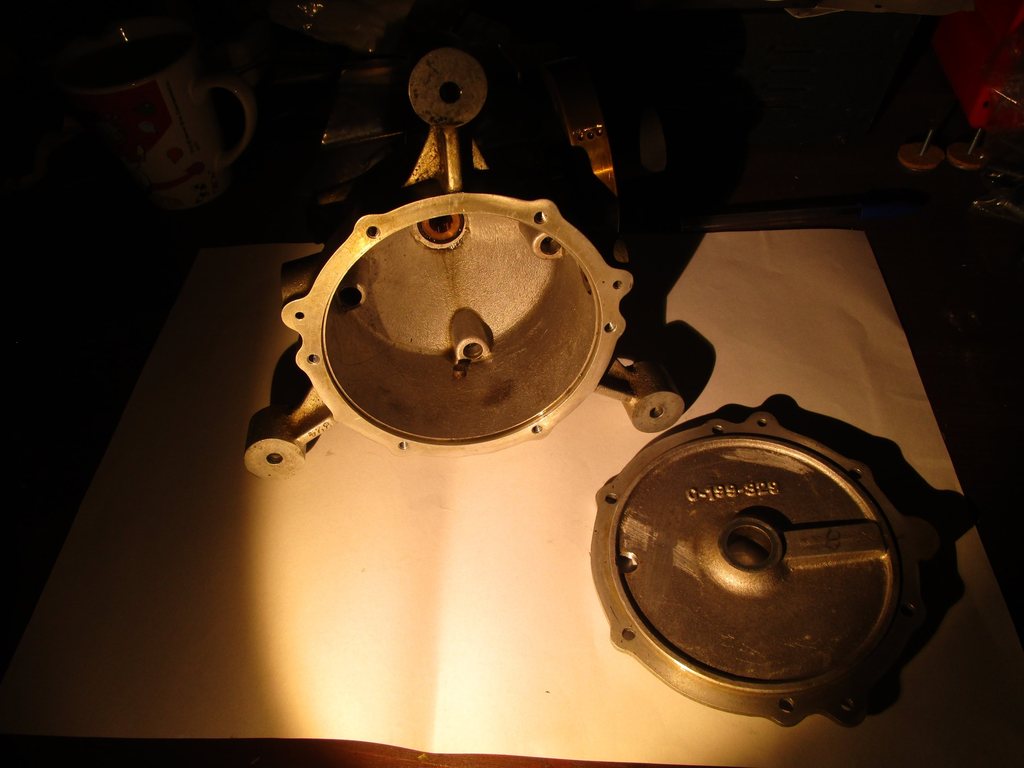

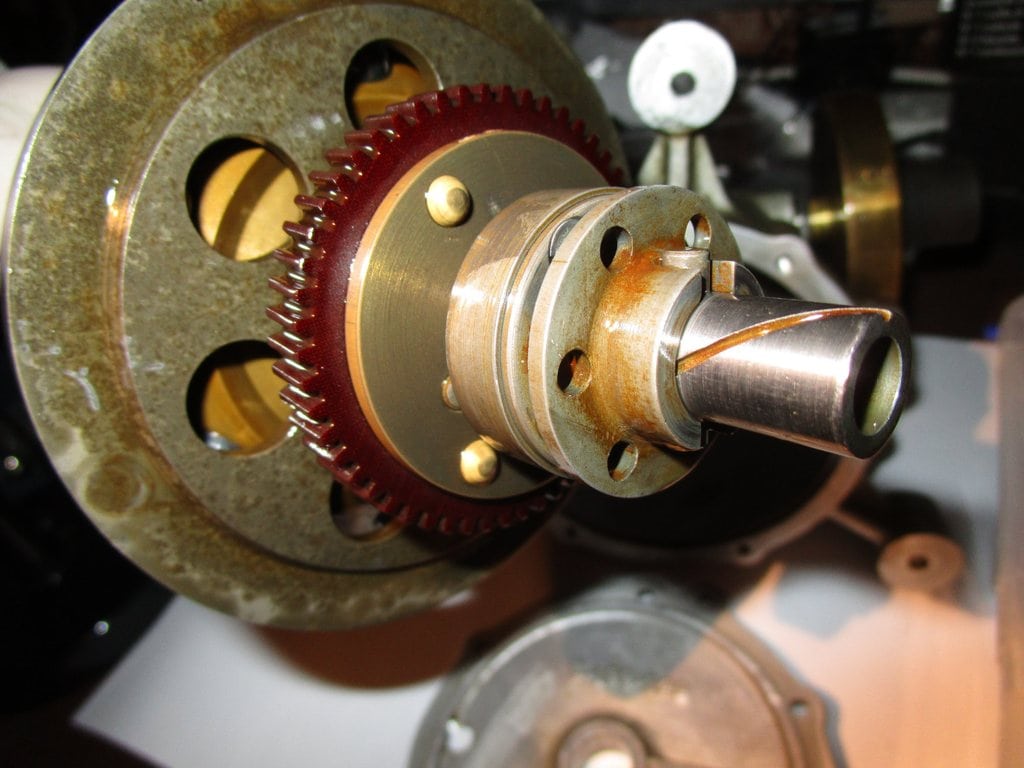

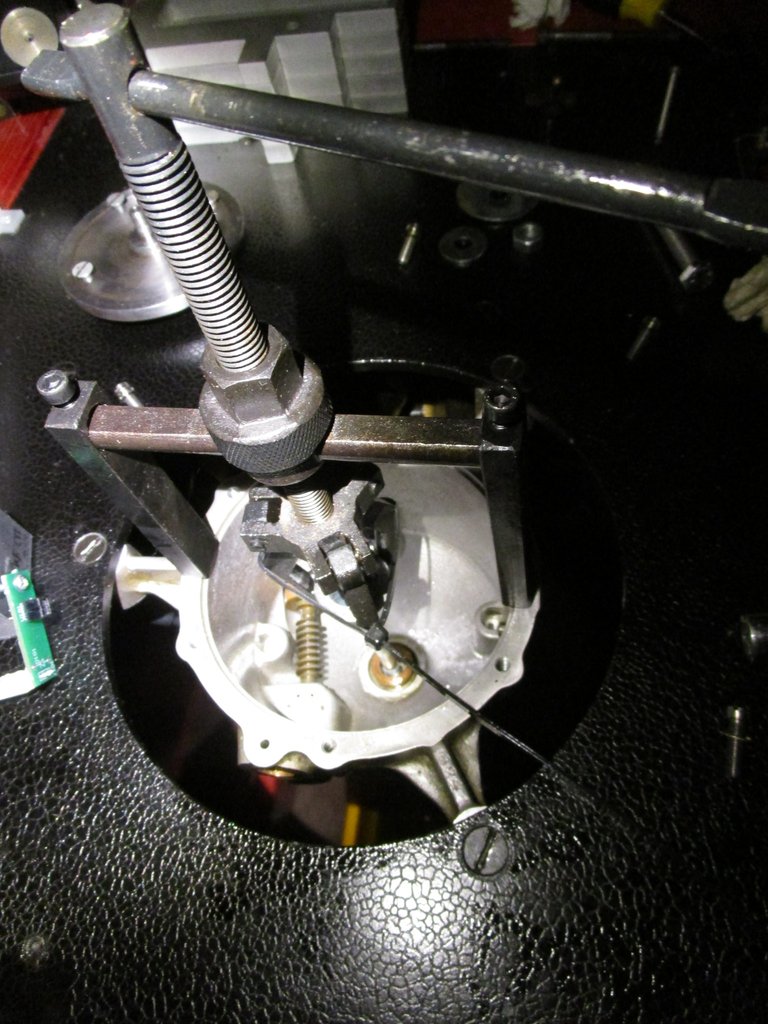

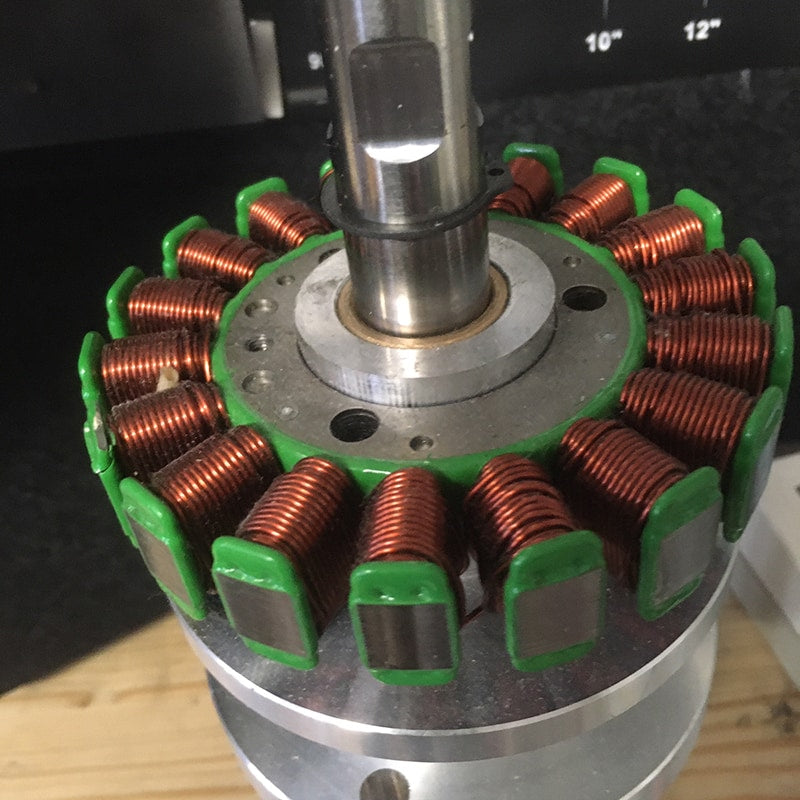

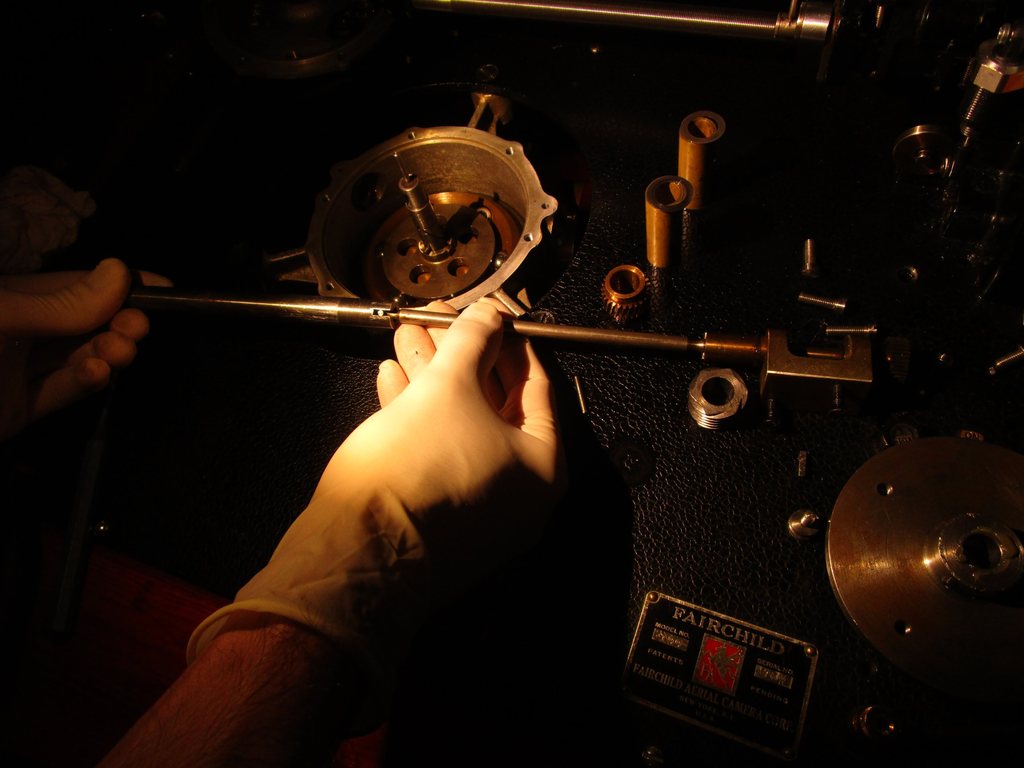

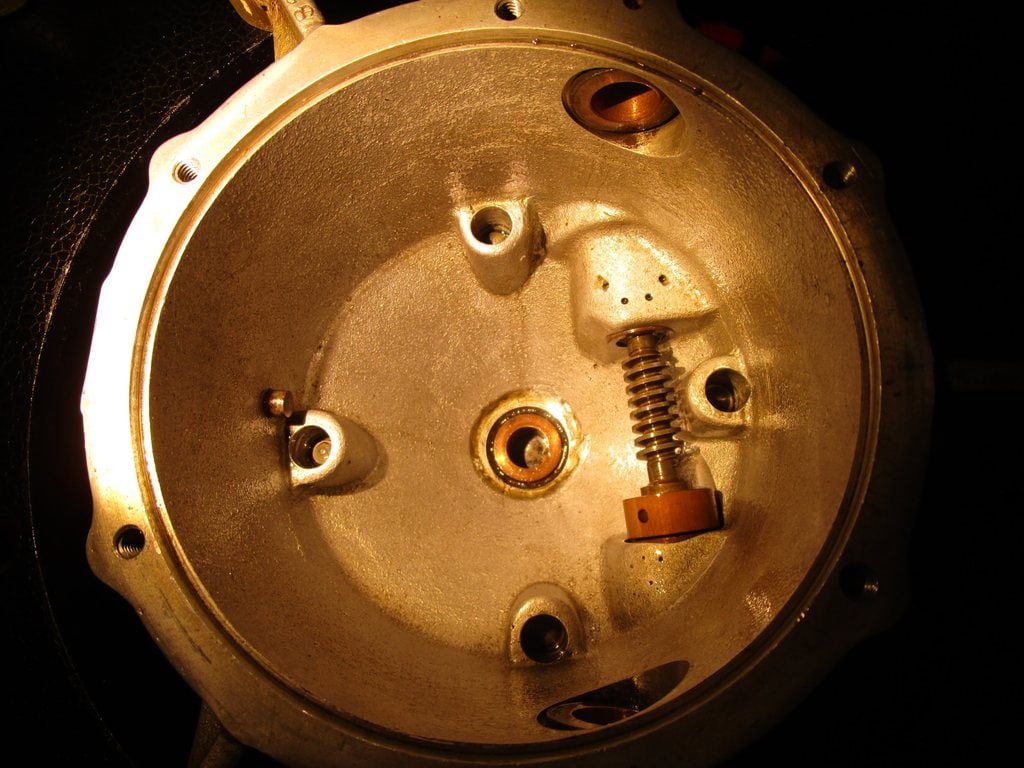

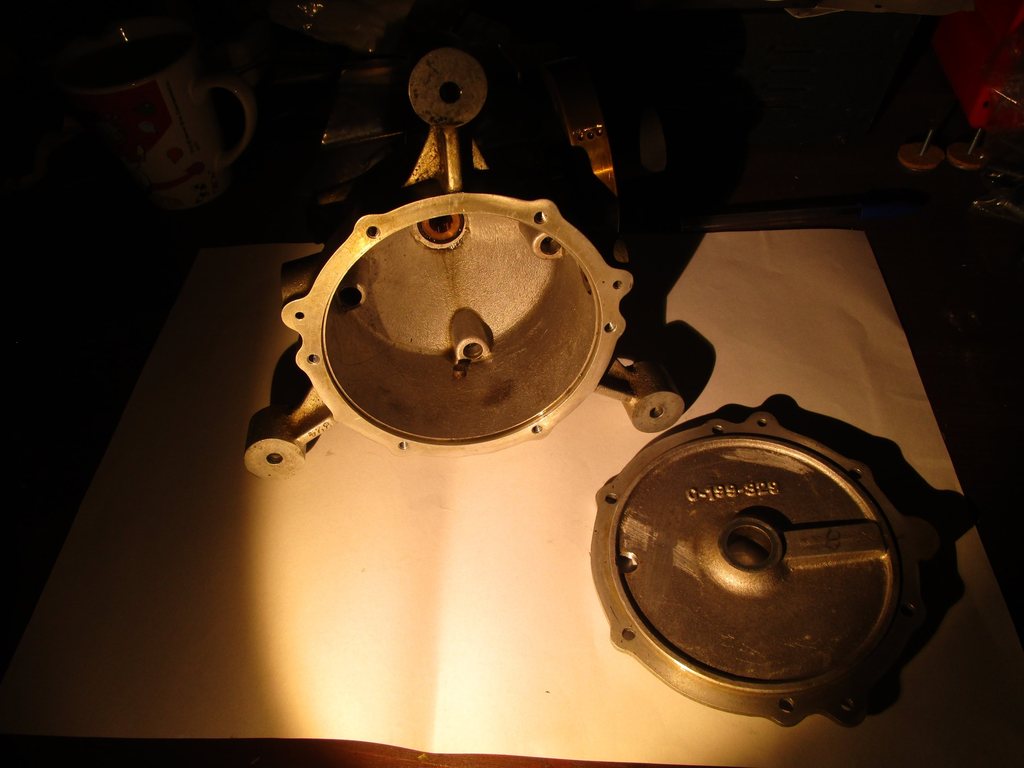

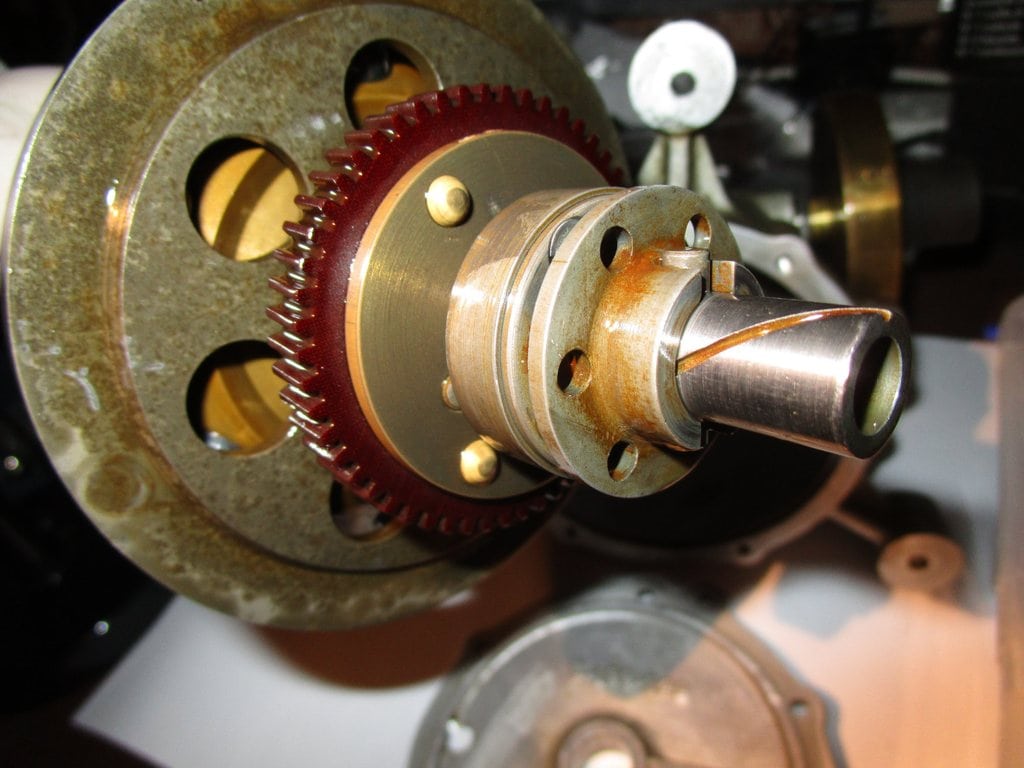

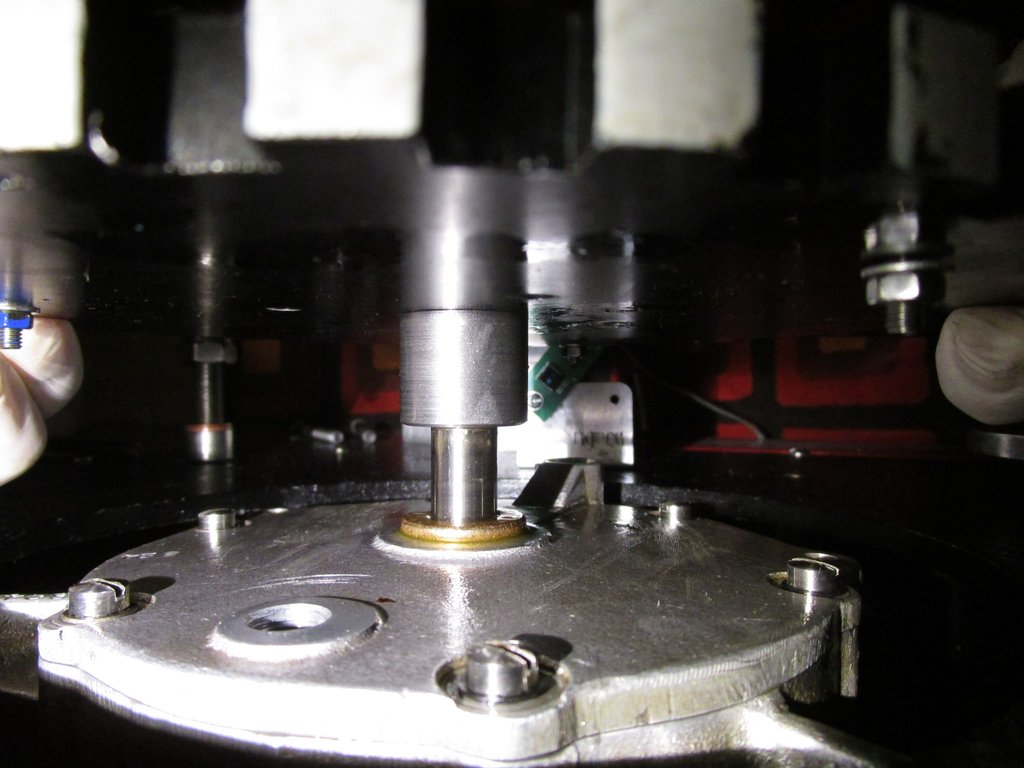

Gearbox overhaul

Now the tiny details are really starting to show. Bearing noises, clattering sounds, rumble, and so on. Time to get dirty and do a full-on gearbox overhaul. While we are at it, why not also get the lead screw sorted out?

We actually had to disassemble and put the gearbox back together twice on this machine. The first time was to measure the bearing dimensions and purchase replacements, and adjust the assembly without replacing parts. This kept it running for a bit longer until all the bearings could be found. Some proved very difficult to source, so, as soon as we found any stock, we purchased all of it, to have a good supply. We probably hold the last remaining stock for some of these bearings, and they are running out fast as we rebuild gearboxes and supply other Fairchild lathe owners. When our stock runs out, the only way to keep these lathes running will be to modify the gearboxes to be able to make use of other bearing types which are actually in current manufacture. We can do such modifications in-house, when the need arises. The second disassembly and reassembly was to replace the bearings when all the parts had arrived. Should you require modification or repair work on disk recording lathe motors or gearboxes, do not hesitate to

get in touch.

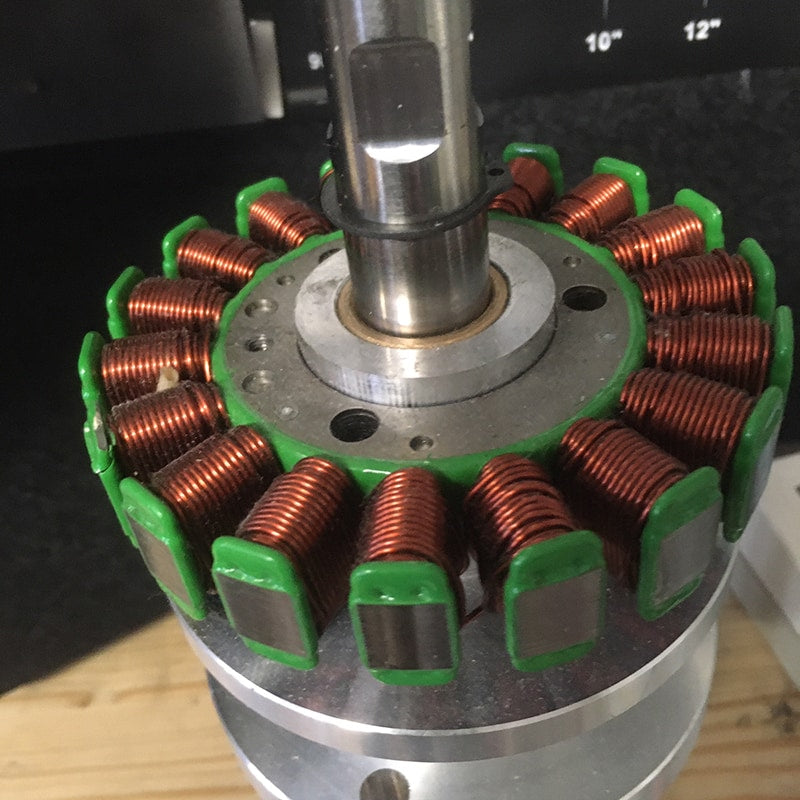

Beautiful engineering! Considering that this was actually made in the 1930's, long before CAD, CNC, and digital measurement tools had even been dreamed of, it is absolutely astonishing! The precision of this assembly, the quality of the materials, and the level of craftsmanship would put to shame most modern manufacturing! You can tell that Fairchild was also manufacturing aircraft! No wonder that even nowadays, for the most demanding precision engineering work, manually operated

machine tools from the 1950's and even earlier are still being used. They really did use their knowledge, understanding of science, and abilities to their full potential back then, and their results are often still unsurpassed. To be fair though, this is not because it cannot be done as good at present, but simply that it is unfortunately seen as uneconomical to work to such high standards.

Pitch Control

In original form, the Fairchild Model 199 and the almost identical Model 539 were essentially fixed pitch machines, in that the pitch could not be altered during the cut. The operator had a choice of four pitches, ranging from 96 to 161 LPI, which could be selected by means of changewheels, as in early screw cutting lathes. Changewheels are little gears that can be changed out only when the lathe is not in operation. Once the lathe starts spinning, the pitch is defined by the gear installed. A lever is provided to select between inside-out and outside-in direction of cut and there was a fixed relationship between platter speed and pitch, resulting in highly accurate, constant groove spacing. However, it is possible to fit more music per side if the grooves can be made to come closer to each other during silent passages, and the spacing between them opened up for loud passages. This can be achieved manually with electronic pitch control, or automatically with a suitable pitch automation system. The Fairchild was first converted to manually variable electronic pitch control, and a Pitch13 automation system was eventually installed.

Dashpot

The previously made, enclosed dashpot, proved difficult to adjust, so a new head mount adapter was made, with a built-in oil cylinder, along with a plunger. At first, the plunger was made simple and non-adjustable, but was soon replaced with Type 6022, our standard high performance adjustable plunger. This setup allows the vertical damping to be fine-tuned, an essential feature for cutting stereophonic records, where quality matters.

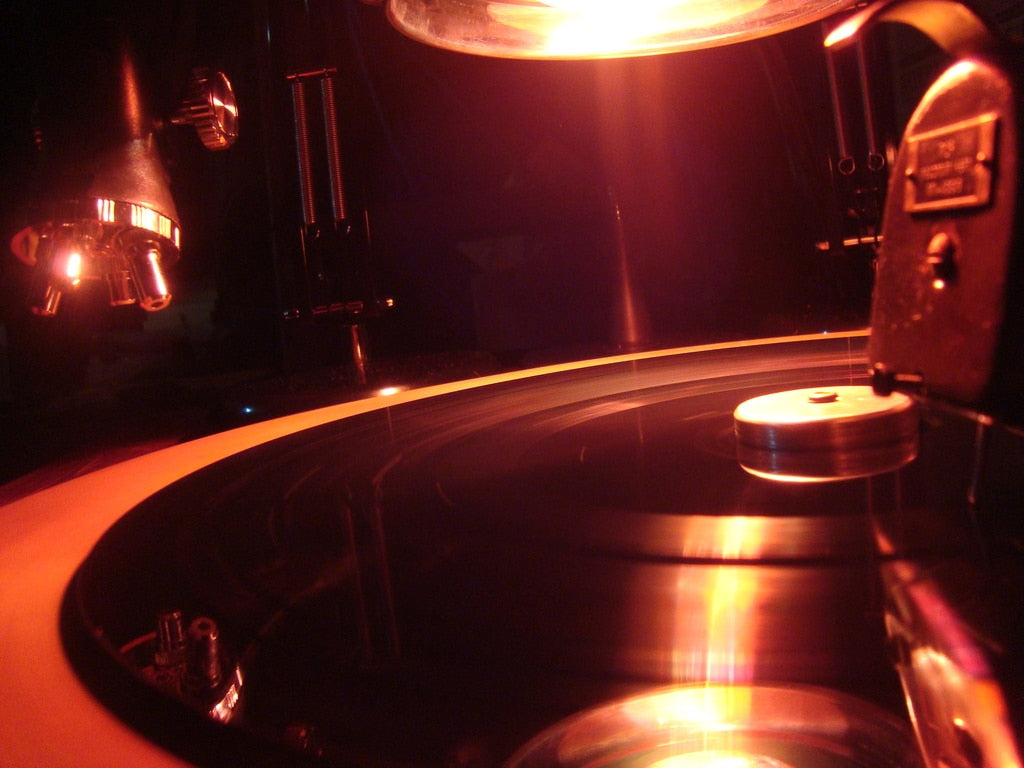

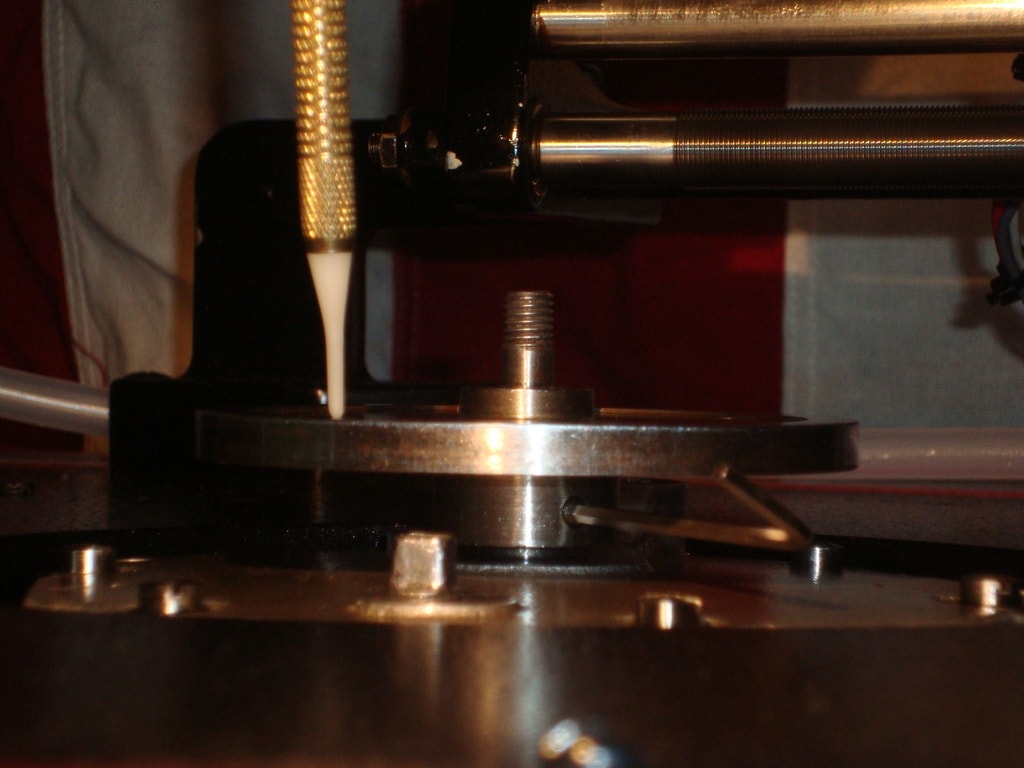

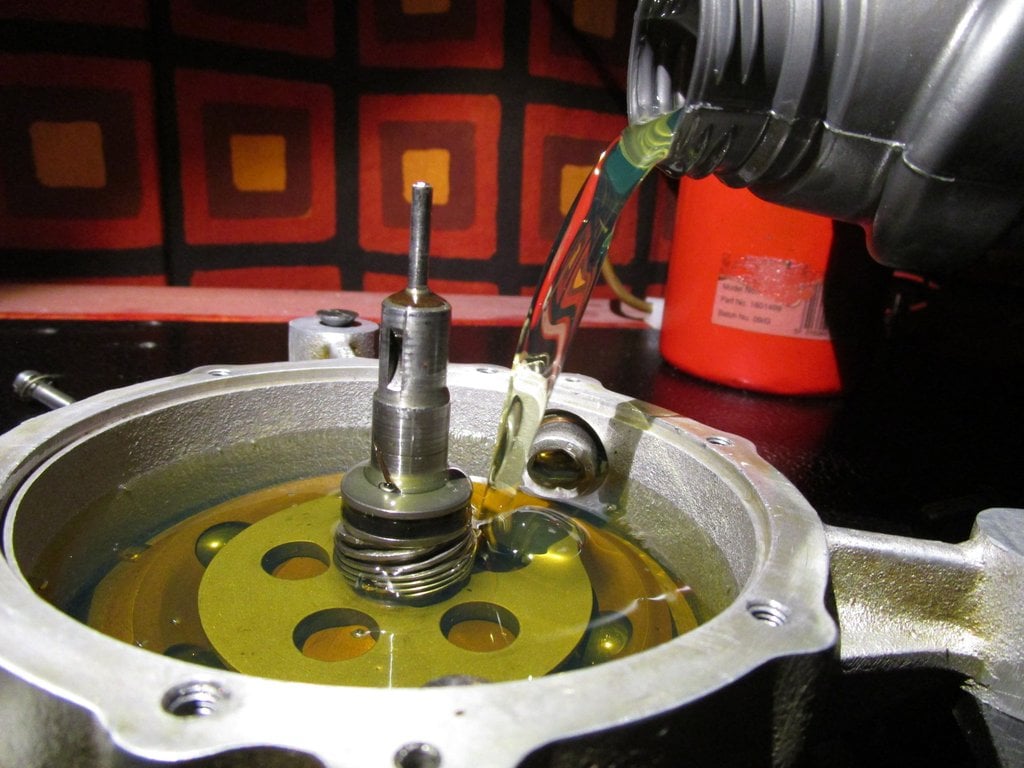

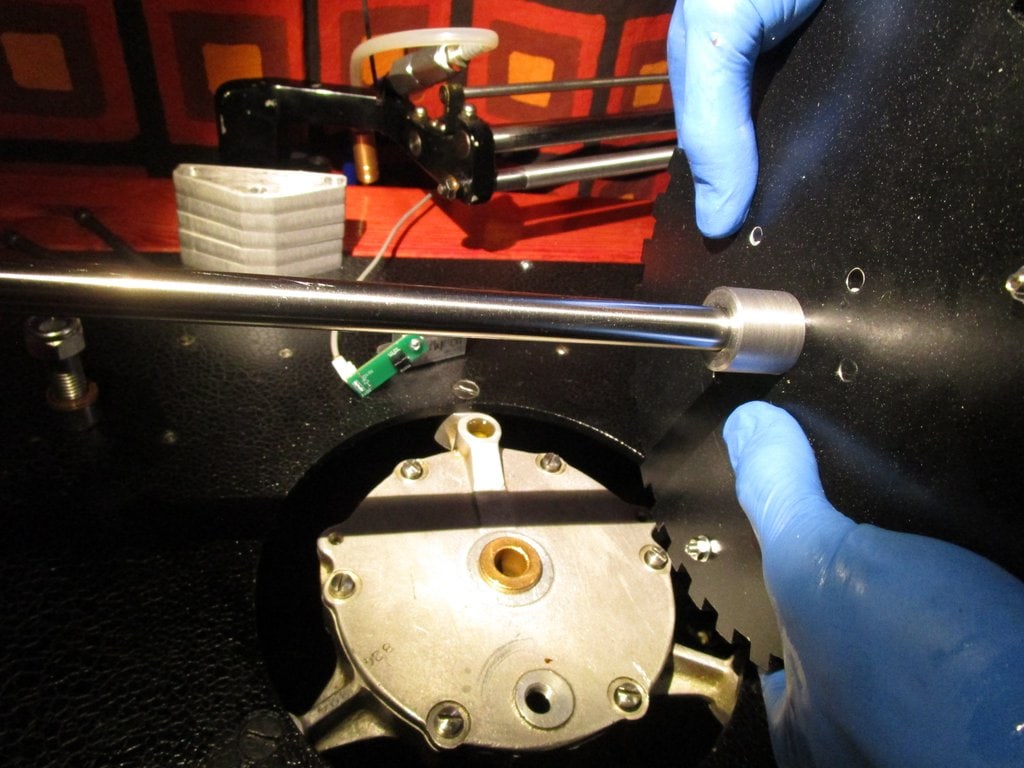

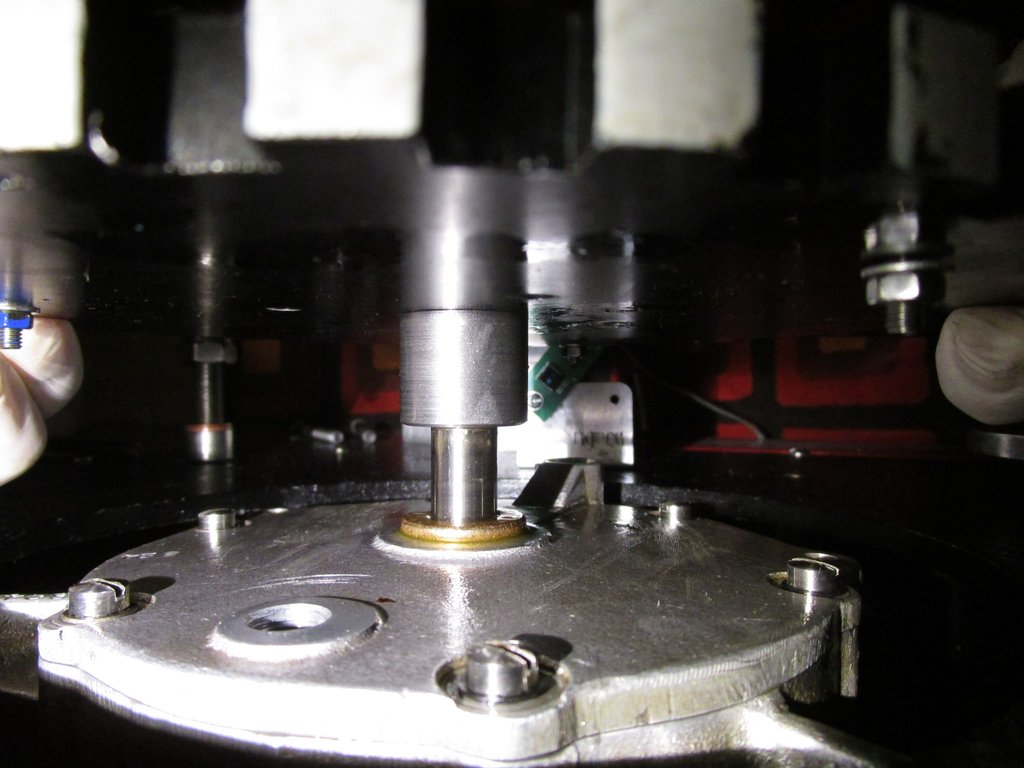

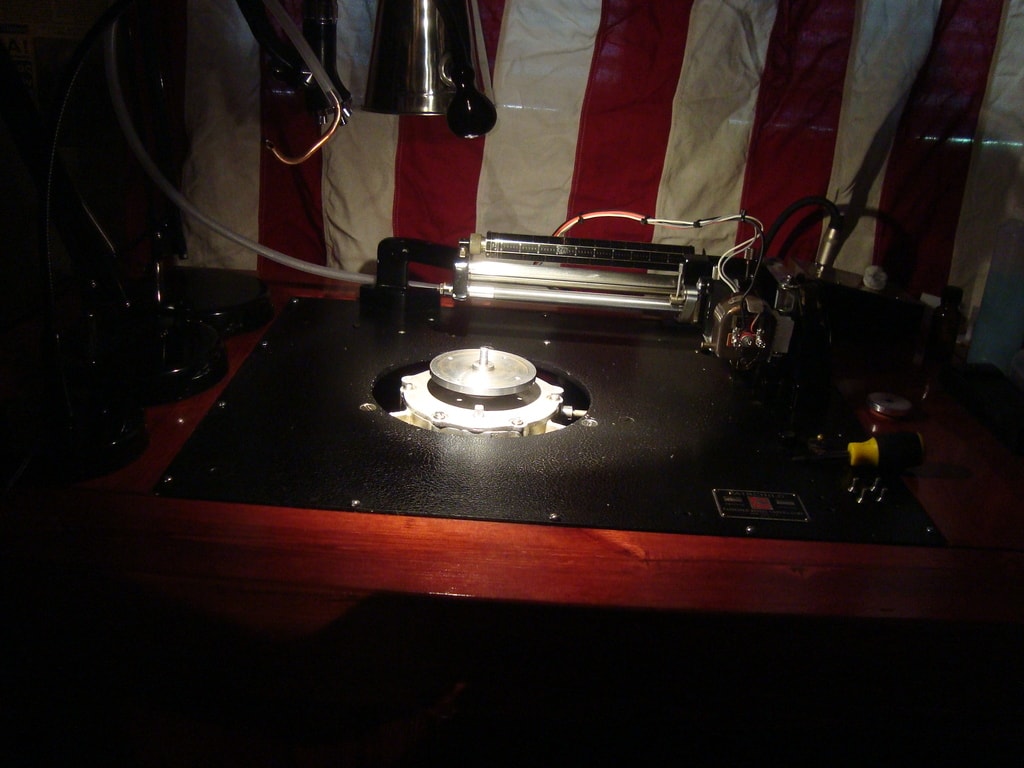

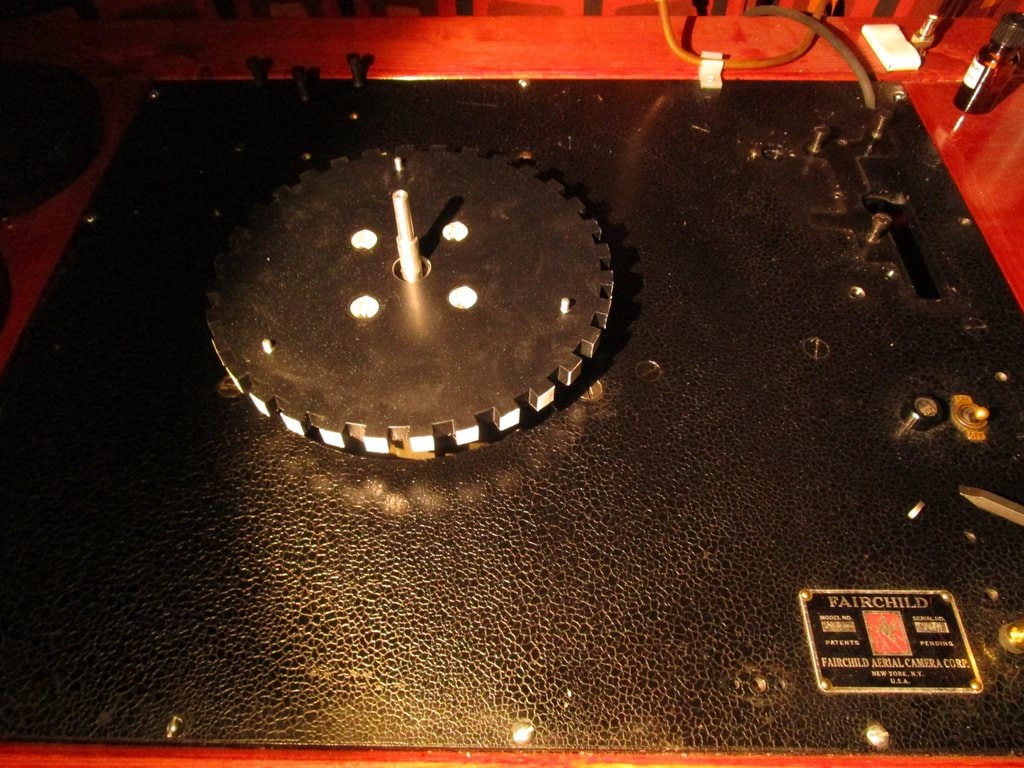

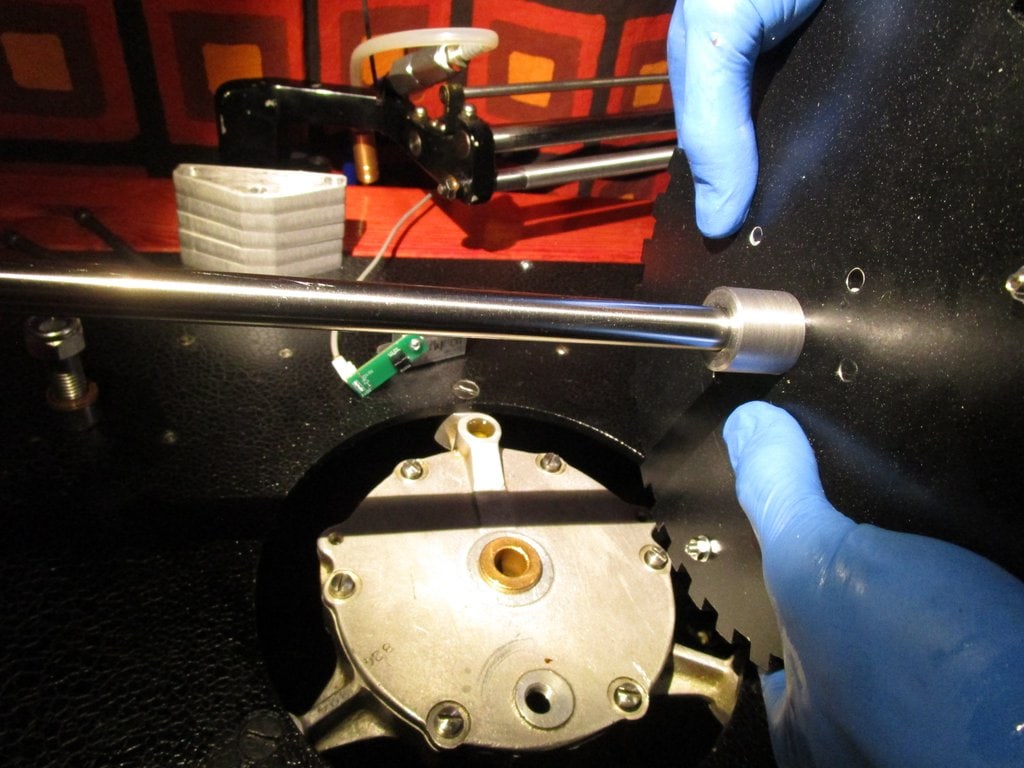

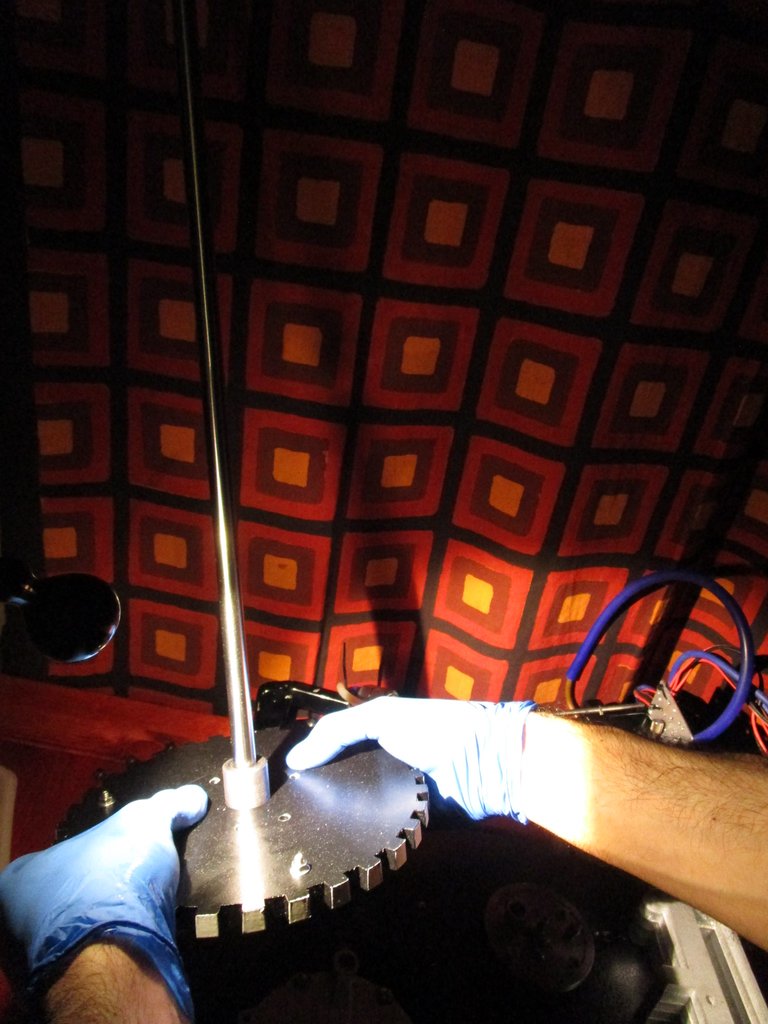

Platter upgrade

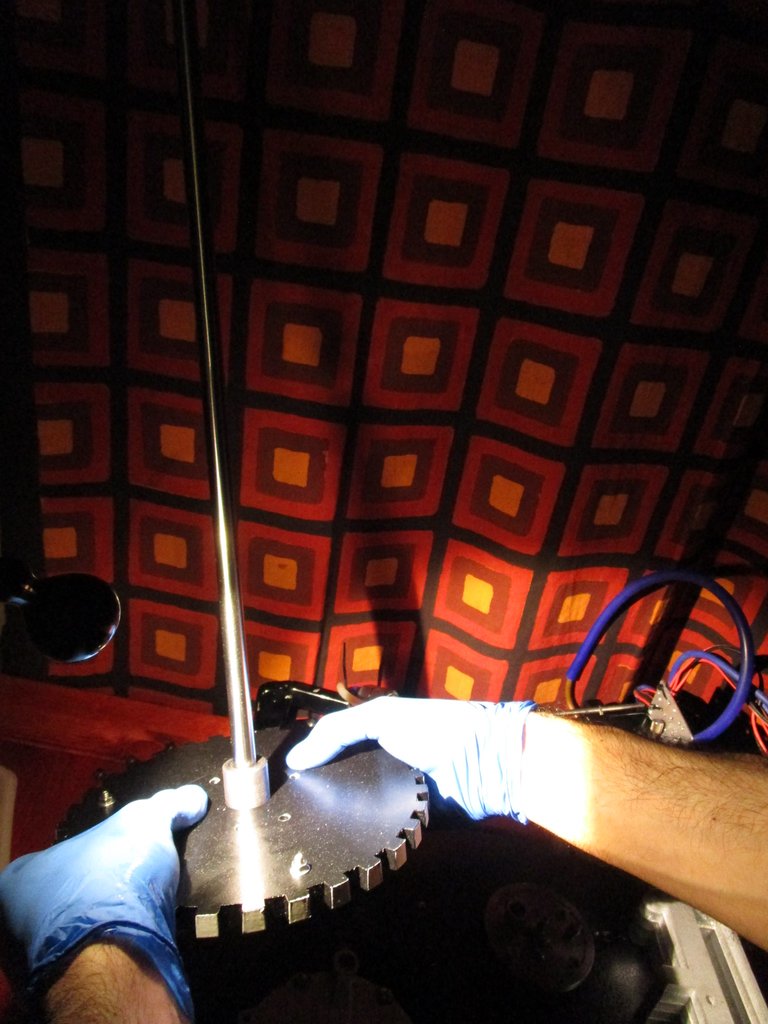

So, with the gearbox running as good as new, the platter was no longer satisfactory. Apart from the warping which made it impossible to true it up to the required level of accuracy, it also suffered from an additional major disadvantage: It was made of cast iron, which interacts with the stray magnetic field of a stereophonic cutter head (monophonic heads have weaker fields so it is usually not much of a problem) and ruins the depth of cut adjustment. Additionally, as mentioned earlier, the puck clamping of the blank disk is really not a good idea if you are trying to do professional work. The obvious choice was to fit a Neumann-style vacuum clamp-down platter, made of a suitable aluminum alloy to very precise dimensional standards (which means flat as can be). We first had to make a sub-platter with height adjusters and a new hollow spindle, to act as an air channel for evacuating the platter. The teeth around the subplatter provide the impulse to a speed/positioning sensor, to interface with

automatically variable pitch and electronic speed regulation systems.

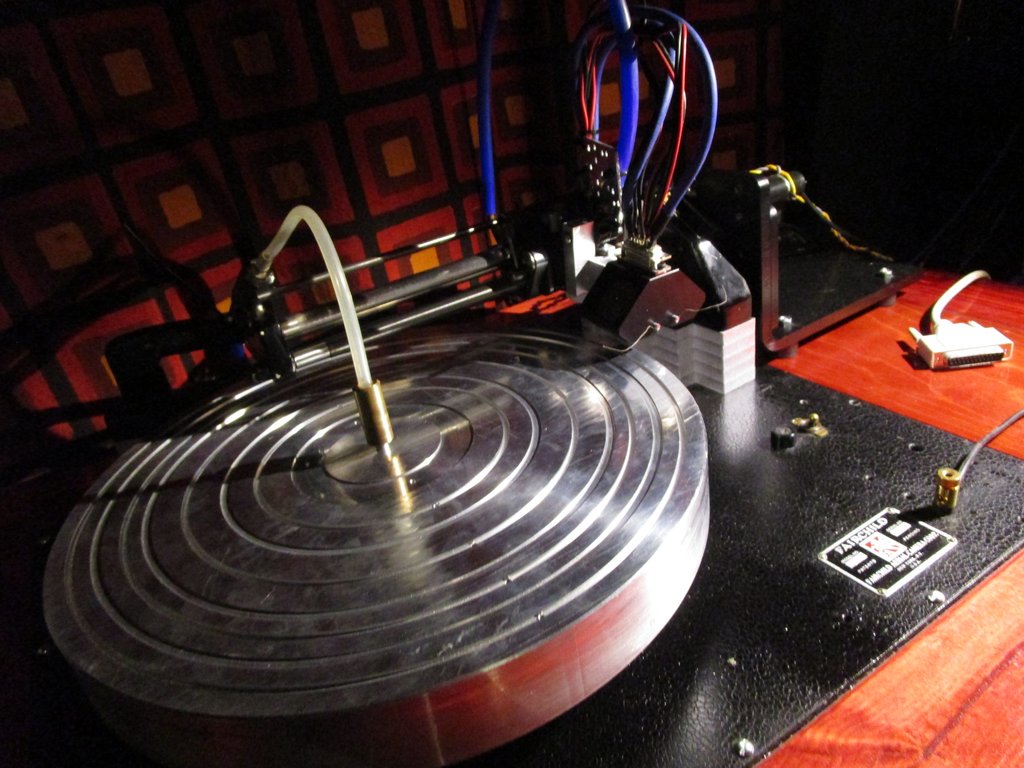

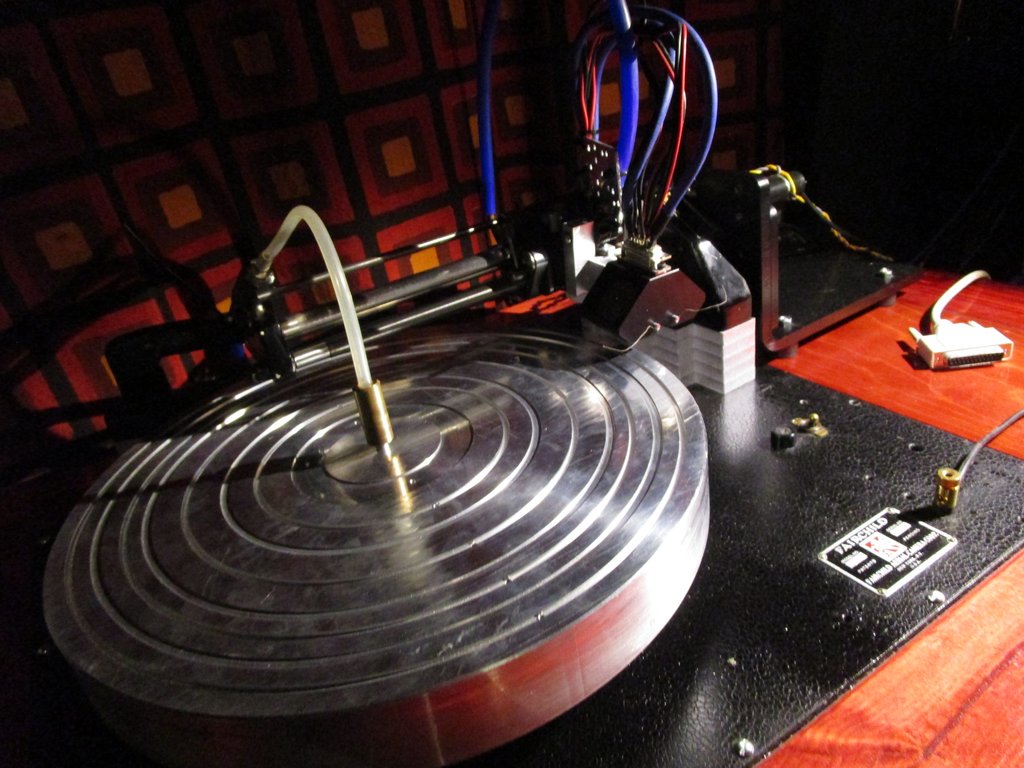

The platter is fitted on top of the new sub platter and spindle assembly. A vacuum hose is fitted to the top of the spindle, over the blank disk, and the resulting vacuum firmly clamps the disk onto the platter and most importantly, flattens it out, should it have any tendency towards warping.

The 16" platter worked well, but proved uncomfortably and unnecessarily large, leaving very little room for access to other parts. While the rebuilt gearbox now offered extremely stable and quiet operation, it only ran at 33 1/3 rpm, since the 78 rpm step-up parts were removed, to reduce rumble. By this point, I felt it was time to take this lathe to the next level! A custom 14" vacuum platter was machined from an aluminum/magnesium alloy (very similar to the one we made for the

Scully lathe project a while ago), a new center bearing assembly was designed, machined and installed, a long shaft was fitted and a massive, floor standing precision motor with electronic speed regulation was installed. The Fairchild has been converted to direct-drive!

Now the platter can spin at any speed from 0 to 120 rpm with extreme stability and no rumble whatsoever. In the presence of a "preview" signal, arriving at the automation system in advance of the same signal reaching the cutterhead, the spacing between the grooves can be automatically and dynamically altered, in proportion to the amplitude of the audio signal, calculating the required space along with platter rotary positioning. In the analog domain, when cutting records from tape, a preview head tape machine is required, to derive the preview signal. With digital sources, the "program" signal can be digitally delayed. However, with live sources, as in direct-to-disk recording, there can be no preview signal. In such cases, the lathe can be switched to manual mode, the pitch being varied in real time by an engineer with strong nerves.

The heavily modified lathe is now regularly used to cut masters for vinyl record manufacturing. Fairchild lathes, being solidly engineered, make an excellent basis for extensive modification and can result in systems offering performance and functionality giving any of the more modern "status symbol" lathes a good run for their money! I suspect we may be seeing more and more of the vintage Fairchild machines in professional use, as the supply of Neumann and Scully lathes is in a salvageable state is rapidly drying up.

I had a really interesting moment some years ago, when I was preparing to solder in some of the automation circuits for that lathe. It suddenly occured to me that I was about to solder a brand-new, state-of-the-art SMD chip, manufactured by Fairchild Semiconductor, on a 1930's disk recording lathe, manufactured by the Fairchild Aerial Camera Cortporation...! - J. I. Agnew

The easiest way to go is embossing/impressing, rather than cutting the grooves on the blank record. This process relies entirely on plastic deformation rather than the removal of material. As such, no suction system is needed to remove the chip, since there is no chip/swarf produced. It does work best warmed up with a heat lamp though, so we put one together. The platter was far from running true and the gearbox was noisy, most likely due to lack of proper lubrication in the past.

The easiest way to go is embossing/impressing, rather than cutting the grooves on the blank record. This process relies entirely on plastic deformation rather than the removal of material. As such, no suction system is needed to remove the chip, since there is no chip/swarf produced. It does work best warmed up with a heat lamp though, so we put one together. The platter was far from running true and the gearbox was noisy, most likely due to lack of proper lubrication in the past.

Precise measurements were taken to verify where the problem lies. The platter was not very flat and the mounting method left very little room for adjustment. It had to be modified.

Precise measurements were taken to verify where the problem lies. The platter was not very flat and the mounting method left very little room for adjustment. It had to be modified.

A stereophonic feedback cutter head of course also needs a serious amount of electronics and a different chip suction arrangement. The need for a high performance cutting amplifier system and the lack of any commercially available products at the time, resulted in the development of the Type 891, described in detail in

A stereophonic feedback cutter head of course also needs a serious amount of electronics and a different chip suction arrangement. The need for a high performance cutting amplifier system and the lack of any commercially available products at the time, resulted in the development of the Type 891, described in detail in

We actually had to disassemble and put the gearbox back together twice on this machine. The first time was to measure the bearing dimensions and purchase replacements, and adjust the assembly without replacing parts. This kept it running for a bit longer until all the bearings could be found. Some proved very difficult to source, so, as soon as we found any stock, we purchased all of it, to have a good supply. We probably hold the last remaining stock for some of these bearings, and they are running out fast as we rebuild gearboxes and supply other Fairchild lathe owners. When our stock runs out, the only way to keep these lathes running will be to modify the gearboxes to be able to make use of other bearing types which are actually in current manufacture. We can do such modifications in-house, when the need arises. The second disassembly and reassembly was to replace the bearings when all the parts had arrived. Should you require modification or repair work on disk recording lathe motors or gearboxes, do not hesitate to

We actually had to disassemble and put the gearbox back together twice on this machine. The first time was to measure the bearing dimensions and purchase replacements, and adjust the assembly without replacing parts. This kept it running for a bit longer until all the bearings could be found. Some proved very difficult to source, so, as soon as we found any stock, we purchased all of it, to have a good supply. We probably hold the last remaining stock for some of these bearings, and they are running out fast as we rebuild gearboxes and supply other Fairchild lathe owners. When our stock runs out, the only way to keep these lathes running will be to modify the gearboxes to be able to make use of other bearing types which are actually in current manufacture. We can do such modifications in-house, when the need arises. The second disassembly and reassembly was to replace the bearings when all the parts had arrived. Should you require modification or repair work on disk recording lathe motors or gearboxes, do not hesitate to

Beautiful engineering! Considering that this was actually made in the 1930's, long before CAD, CNC, and digital measurement tools had even been dreamed of, it is absolutely astonishing! The precision of this assembly, the quality of the materials, and the level of craftsmanship would put to shame most modern manufacturing! You can tell that Fairchild was also manufacturing aircraft! No wonder that even nowadays, for the most demanding precision engineering work, manually operated

Beautiful engineering! Considering that this was actually made in the 1930's, long before CAD, CNC, and digital measurement tools had even been dreamed of, it is absolutely astonishing! The precision of this assembly, the quality of the materials, and the level of craftsmanship would put to shame most modern manufacturing! You can tell that Fairchild was also manufacturing aircraft! No wonder that even nowadays, for the most demanding precision engineering work, manually operated

The platter is fitted on top of the new sub platter and spindle assembly. A vacuum hose is fitted to the top of the spindle, over the blank disk, and the resulting vacuum firmly clamps the disk onto the platter and most importantly, flattens it out, should it have any tendency towards warping.

The platter is fitted on top of the new sub platter and spindle assembly. A vacuum hose is fitted to the top of the spindle, over the blank disk, and the resulting vacuum firmly clamps the disk onto the platter and most importantly, flattens it out, should it have any tendency towards warping.

The 16" platter worked well, but proved uncomfortably and unnecessarily large, leaving very little room for access to other parts. While the rebuilt gearbox now offered extremely stable and quiet operation, it only ran at 33 1/3 rpm, since the 78 rpm step-up parts were removed, to reduce rumble. By this point, I felt it was time to take this lathe to the next level! A custom 14" vacuum platter was machined from an aluminum/magnesium alloy (very similar to the one we made for the

The 16" platter worked well, but proved uncomfortably and unnecessarily large, leaving very little room for access to other parts. While the rebuilt gearbox now offered extremely stable and quiet operation, it only ran at 33 1/3 rpm, since the 78 rpm step-up parts were removed, to reduce rumble. By this point, I felt it was time to take this lathe to the next level! A custom 14" vacuum platter was machined from an aluminum/magnesium alloy (very similar to the one we made for the

Now the platter can spin at any speed from 0 to 120 rpm with extreme stability and no rumble whatsoever. In the presence of a "preview" signal, arriving at the automation system in advance of the same signal reaching the cutterhead, the spacing between the grooves can be automatically and dynamically altered, in proportion to the amplitude of the audio signal, calculating the required space along with platter rotary positioning. In the analog domain, when cutting records from tape, a preview head tape machine is required, to derive the preview signal. With digital sources, the "program" signal can be digitally delayed. However, with live sources, as in direct-to-disk recording, there can be no preview signal. In such cases, the lathe can be switched to manual mode, the pitch being varied in real time by an engineer with strong nerves.

Now the platter can spin at any speed from 0 to 120 rpm with extreme stability and no rumble whatsoever. In the presence of a "preview" signal, arriving at the automation system in advance of the same signal reaching the cutterhead, the spacing between the grooves can be automatically and dynamically altered, in proportion to the amplitude of the audio signal, calculating the required space along with platter rotary positioning. In the analog domain, when cutting records from tape, a preview head tape machine is required, to derive the preview signal. With digital sources, the "program" signal can be digitally delayed. However, with live sources, as in direct-to-disk recording, there can be no preview signal. In such cases, the lathe can be switched to manual mode, the pitch being varied in real time by an engineer with strong nerves.

The heavily modified lathe is now regularly used to cut masters for vinyl record manufacturing. Fairchild lathes, being solidly engineered, make an excellent basis for extensive modification and can result in systems offering performance and functionality giving any of the more modern "status symbol" lathes a good run for their money! I suspect we may be seeing more and more of the vintage Fairchild machines in professional use, as the supply of Neumann and Scully lathes is in a salvageable state is rapidly drying up. I had a really interesting moment some years ago, when I was preparing to solder in some of the automation circuits for that lathe. It suddenly occured to me that I was about to solder a brand-new, state-of-the-art SMD chip, manufactured by Fairchild Semiconductor, on a 1930's disk recording lathe, manufactured by the Fairchild Aerial Camera Cortporation...! - J. I. Agnew

The heavily modified lathe is now regularly used to cut masters for vinyl record manufacturing. Fairchild lathes, being solidly engineered, make an excellent basis for extensive modification and can result in systems offering performance and functionality giving any of the more modern "status symbol" lathes a good run for their money! I suspect we may be seeing more and more of the vintage Fairchild machines in professional use, as the supply of Neumann and Scully lathes is in a salvageable state is rapidly drying up. I had a really interesting moment some years ago, when I was preparing to solder in some of the automation circuits for that lathe. It suddenly occured to me that I was about to solder a brand-new, state-of-the-art SMD chip, manufactured by Fairchild Semiconductor, on a 1930's disk recording lathe, manufactured by the Fairchild Aerial Camera Cortporation...! - J. I. Agnew