[This is a little different from previous Copper interviews as its subject passed away in 2015. John Seetoo interviewed Dennis Ferrante some time ago, and this is the first publication of their chat. John has also provided an annotated list of some of Dennis’ credits which helps us to have a better idea of Ferrante’s notable accomplishments. —Ed.]

This past June marked the 2nd anniversary of the passing of my good friend and music engineering mentor, Dennis Ferrante, from a heart attack which took him at age 65. Brash, opinionated, incredibly talented and musical, Dennis was part of the NYC Record Plant East team assembled by Roy Cicala that included Jimmy Iovine, Jack Douglas, Shelly Yakus, and others who were responsible for a large portion of classic rock from the late 1960s through the 1980’s with records from John Lennon, Aerosmith, Lou Reed, and many others.

After Record Plant East closed, Dennis joined RCA studios, where he worked on records with Wynton and Branford Marsalis, SWV, Joe Jackson and many other artists, as well as remixed and remastered several CD boxed sets from RCA’s archives, including his Elvis Presley work with historian Ernst Jorgensen. Dennis won a Grammy Award in 1999 for Best Historical Album from his work on the Duke Ellington CD boxed set, Centennial Edition: Complete RCA Victor Recordings: 1927-1973.

From The Rock Station 97.7 on Dennis Ferrante’s Obituary notice:

Longtime friend, bandmate, and colleague, producer Jack Douglas posted on his Facebook page: “I am so shocked and saddened to hear of the loss of my dear friend Dennis Ferrante. We worked and played together almost 50 years. One of the best. I will miss him.”

- Ferrante’s resume reads like a who’s-who in popular music, but to rock fans, two acts will always be associated with Ferrante — John Lennon and the Raspberries. Ferrante, who was nicknamed “The Fly,” worked with Lennon throughout the 1970’s on such albums as Imagine, Some Time In New York City, Mind Games, Walls And Bridges, and Rock ‘N’ Roll, along with the Lennon-produced Harry Nilsson album, Pussycats.

I managed to interview Dennis in between mixing sessions he was doing for a Bo Diddley live concert album.—John Seetoo.

—–

John: Engineering has changed dramatically in the last 10 years as digital recording has made multitrack home recording ubiquitous. What skills do you think are more easily developed by working in a professional studio that can’t be replicated in the home environment?

Dennis: In my opinion, catching the synergy between musicians as the song develops. There is a vibe that happens in the room when musicians can see each other that’s lost when everything is done individually. I get excited when I see a song come together in a “live “situation as opposed to doing all tracks separately.

John: Do you have a standard protocol when doing a mix from scratch?

Dennis: I put up the entire song without any enhancement of any kind. Then I let the song dictate to me what it needs. Too many engineers immediately reach for the EQ button without listening first. If the song is recorded well, you don’t have to EQ the daylights out of it to make it sound good.

John: We have worked together in the past and you are a strong advocate for rhythm guitars, acoustic or electric, to help any kind of track. Keith Richards also is a fan of acoustic rhythm guitar to help a song jell. Any special philosophy behind this approach?

Dennis: Well, to me the acoustic guitar is like adding roundness to any song. It gives a fullness to which the rest of the mix can be built on. I like to build my mixes with the bass drum, bass, keys (if there are any), rhythm guitar and lead vocal. If you can get that sounding good, everything else should fall into place.

John: You did engineering work on countless records, including some classics, but some of the standouts include Lou Reed’s Berlin, Don McLean’s American Pie, and John Lennon’s Imagine, Rock and Roll, and Walls and Bridges. What do you recall about making those records, and are there any specific anecdotes you can tell us, specifically with regard to microphones, techniques, or problems that had to be overcome?

Dennis: Well, Berlin wasn’t too hard to mix because of the musicians on that album. Great players make mixing a joy because they just play what’s needed and don’t fill in all the “holes”. American Pie was my first outing as an Assistant Engineer. I worked with an engineer named Tom Flye on that one who was a Record Plant engineer at that time. I’m also one of the guys singing on the end of the song.

Working with John (Lennon) was an incredible experience. He was easy to work with and fun to record. Although he hated the sound of his vocal with no effect on it while recording, he trusted me enough to tell him when I thought he got the performance. He said that the more effects one put on his voice, the better it made him sing. All the engineers at the Record Plant used basically the same mikes all the time. You’ve got to learn the characteristics of each mike and how it sounded on certain instruments in all of the rooms we had. There were certain characteristics in each studio but everyone knew how to work with them to achieve great sounding records.

John had a wicked sense of humor. One time, he was watching the multi track deck rewind and asked me what would happen if there was no take up reel. I told him the tape would shoot out all over the floor. He said, “Great. Put some blank tape on and let’s play a trick on Roy (Cicala).” So we loaded up some blank tape and John hit the switch. Like I said, the tape spooled out all over the floor. John starts yelling,”Fuck! That’s my Master!” Roy rushes in, looks down at the floor, and his jaw hits the ground in shock! He gets on his hands and knees and starts slowly reeling it up by hand, apologizing to John the whole time. John keeps on grumbling, winking at me behind Roy’s back. We finally both burst out laughing! Roy turns, looks at the half rewound reel, then stares at us. It took him a few seconds to realize he got punked!

John: What was it like to work at Record Plant East with Roy Cicala and some of your colleagues, like Jimmy Iovine, Shelly Yakus and Jack Douglas, among others?

Dennis: Roy Cicala, Shelly Yakus, Jay Messina, Carmine Rubino, Tom Flye, and Jack Douglas were probably and still are, the most remarkable and talented engineers ever to come out of the Record Plant (and humbly, myself ). We recorded so many hit records back then it boggles the mind. I am proud to say that I was Roy’s protégé at that time and along with him and the other engineers I learned my craft very well, as some people have told me. Jimmy Iovine, on the other hand, was my assistant in the beginning and then became Roy’s when I started engineering on my own. Who knew what he was capable of back then and where he’d wind up now?

John: You were very involved in the Elvis Presley CD remixes that were produced by Ernst Jorgensen. What were some of the surprises you encountered in listening to those original multitrack reels, and what did you like and dislike about new recording technology that was used on those projects?

Dennis: Earlier Elvis recordings were mono, so we left them they way they originally sounded without the false stereo, echo and what have you. The fun started when I started doing the ‘70’s box set. Here is where I could separate the tracks and with modern technology I could remix them with precise EQ that wasn’t available back then. I only used a little EQ to just separate some instruments sonically from one another making sure to keep the integrity of the new mix to the old one. I used the original machines Elvis used with the same EQ curve that was present back then. I then used mostly analog gear (EQ, Limiters, compressors, etc,) to complete the mixes. I then mixed to a digital PCM 1630 and then edited with the help of a Sony editor. The only thing I didn’t like about the digital technology was the coldness of everything. That’s why I chose to do all the mixing analog to digital.

When I worked on Elvis material from the 1970’s, I managed to get the original multitrack tapes and I found out there were all kinds of extra instruments, like percussion played by Ralph MacDonald, that never made the final releases. The original stereo releases also all sounded a little unbalanced. It turns out that RCA had to send the multitrack tapes to Memphis for the final mixes and their machines weren’t calibrated right, so there was a -10dB discrepancy between the stereo channels. Also, those guys were used to mixing the early 60’s stuff so it looks like just muted the congas and other instruments they were unfamiliar with from the final mixes. Ernst and I restored them and fixed a lot of stuff for the Walk A Mile in My Shoes Elvis boxed set.

John: You worked with Wynton and Branford Marsalis on their first few respective records. In particular, Wynton was frustrated about not achieving a sound that he wanted for his trumpet that you finally solved, after creating a bizarre microphone placement setup and signal chain. Can you please elaborate?

Dennis: Wynton was not happy with the sound of his trumpet when he played. The Columbia engineer doing the session (I was the 2nd engineer on this date) was getting frustrated because inside the control room it sounded fine but the artist wasn’t pleased. So after about 45 minutes, I suggested that I go out in the studio and listen to what was being heard by Wynton. He kept complaining that his trumpet sounded “too small” and that it sounded better when it was recorded on his Walkman (a heavily compressed mic). After about 15 minutes, I realized that Wynton was hearing his instrument from a different perspective which included the ambience of the room (Studio A of RCA studios was about 150 ft long, 60 feet wide and movable ceiling height from 20 feet – 40 feet ). This cavernous room added another dimension to the sound of the trumpet. Additionally, all of a sudden it became clear what I had to do to help the situation. I added another U87 microphone over the top of Wynton’s trumpet to capture some of the ambient room sound just the way Wynton heard it in the room, added a little compression on just that mic and combined it with the other mic being used on the trumpet and when he came into the control room this time, he heard exactly the sound he wanted. The rest of the session went off without any more problems.

John: What would be your dream analog studio setup for recording and mixing?

Dennis: An old Neve desk with a couple of Studer 24’s, lots of Pultec equalizers, a few LA-2a’s (Universal Audio tube compressors), throw in a few UREI 1176’s, a nice selection of analog outboard, a cheeseburger and soda and leave me alone to do my thing.

John: What would be your dream digital studio setup for recording and mixing?

Dennis: I’m old school so I really have no opinion on this topic. I can work with anything. I just need someone else in the room that knows the gear cold. My preference is that I’ll let that person take care of the technical end and leave me to do the creative end. I’ve been recording, mixing and mastering for the last 38 years. Now I like to have fun in a session. Worrying about digital stuff makes me nuts but this is the future, right?

John: You have a Grammy for the Duke Ellington CD Box Set, but your history and pedigree are clearly in rock and roll. What’s in store for Dennis Ferrante for the future, and what advice do you have for musical producers, engineers and artists in the 21st Century?

Dennis: I truly don’t know. I have a band and being a singer since I was 5 yrs old, I enjoy playing out and doing classic rock n’ roll tunes from 1960 – 1980. I feel is when music exploded and great music was being done. That’s why that there are so many reunions of earlier groups happening today and people are flocking to these concerts to relive their youth and try to forget their problems for 2 or 3 hours and just have fun. As far as advice to other producers and engineers in this century it would be this, don’t spend all your time wondering if your work is better than someone else. Do your best and the results will amaze you. Forget about AutoTune and make the artist or whomever keep doing it to get it right. I’ve been on many a session where producers keep going over a certain part to get it technically perfect. That’s fine but you’re forgetting the one most important fact. THE PERFORMANCE. Sometimes mistakes make a record. Just sit back and let the artist do what they do best. Perform. As far as artists in this century, work at your craft no matter what it is. It is not my aim to tell an artist what to do. They have to figure that one out for themselves and hopefully they will.

——

That’s the end of my interview with Dennis. I had the great fortune to work with him in his mixing of the movie, The Source of Power, and the title song. We forged a great friendship and I was able to learn a lot from him on a technical basis, and heard a number of captivating stories about some of the landmark records he worked on. Here are a few that I recall:

Walls and Bridges, Rock and Roll, Imagine – John Lennon

“John always wanted echo or other effects on his vocals. He’d cut great tracks with top players like David Spinozza and then make his voice sound like it was underwater. We all thought it sounded fine as is, but he was JOHN LENNON! I wasn’t going to argue with him!”

Approximately Infinite Universe – Yoko Ono

“I was still a junior engineer at Record Plant and this was going to be my first album engineering credit, so I was real excited. Yoko’s taking down our names, so me and Danny Turbeville, an apprentice, were the last. I was supposed to get Assistant Editor credit, and Jack (Douglas) was the Chief Engineer. Told all my family and friends. Record comes out, and she listed me as “Dennis Turbeville!” I was f***ing livid! I was certain for years she did that on purpose.”

American Pie– Don McLean

“It became a huge song, but at the time, no one knew Don McLean from Don Adams. He booked time during the day, our cheap rate, and I got to assist engineer on it. Long f***ing song, but it was catchy. Cut it pretty quickly. Had to get everyone into the room around a [Neumann] U87 to sing that end chorus. You can hear it’s me singing, especially on that “this’ll be the day ‘til I die” line at the end. Who knew then how big a 9 minute song would get, especially on AM radio?”

Berlin – Lou Reed

The opening piano introduction for the song “Berlin” is an amazingly intimate sound; the piano seems to be right in the room. I repeatedly asked Dennis how he got it, but he would just smile and say, “Trade Secret.” (I personally think it had to do with placing a pair of Neumann U87’s running through UREI 1176 Compressors into a Neve Board, but the placement was the key.) When discussing the album, however:

“Some of the best musicians in rock music were on there – Jack Bruce, (Steve) Hunter and (Dick) Wagner, Steve Winwood, Michael Brecker…hell, I even sang backup on it…it was great hearing all of these guys just play…and then Lou Reed comes in with that voice – his 3 note (vocal) range…it works on the final record, but the difference was comical if you were there at the time. Incredible songs. Even Lou realized it, ‘cause he got better singers to do some of the songs when he did the St. Ann’s album concerts years later.”

Will Power – Joe Jackson

“Studio A at RCA was built for this kind of record. Full orchestra, like what they used to do with Sinatra. It was a trip setting up for so many pieces to play all at the same time so you could hear the room at its full potential. I was also impressed with Joe. I always thought he was just a punk new wave Brit, so when he starts writing out charts for the horns and strings, I did a double take.”

Pussycats – Harry Nilsson

“John (Lennon) and Harry loved playing practical jokes. Who’s the most unlikely musician they should bring in to jam with? They got the idea to jam with Paul Simon. So they get someone to call him, and he shows up with his guitar. Paul plugs in, John shows him the chords and tells him to wait for his cue. Band starts playing, Paul is waiting…and waiting…John says, “how come you didn’t come in?” Paul asks to try again. Band starts playing. Paul is waiting…and waiting…again, John says, “how come you didn’t come in?” Meanwhile, Harry and I are rolling on the floor in the control room! 3rd time, Paul comes in – John stops everything. “I didn’t cue you yet.” Paul storms out and packs up his guitar. “F*** him! I’m just as big as John Lennon!” The whole room goes so silent, you can hear a pin drop. We all know that as big as “Bridge Over Troubled Water” was, that is simply not true. John cracks up, and finally eases the tension. There were lots of moments like that.”

Live From Las Vegas, Elvis at the International, Walk a Mile in My Shoes, Blue Suede Shoes– Various Elvis Presley CD collections

“Working with Ernst (Jorgensen), I got a really good exposure to the whole range of music Elvis covered. You can hear how he was trying to stretch and break out from being pigeonholed. He did gospel, country, rock and roll, all kinds of music. Live, he could still knock it out of the park. When I remixed “An American Trilogy”, there was live video footage with it, so I matched the (stereo) panning to the camera panning.”

Raspberries-The Raspberries

“The Raspberries never got their due. They were a great band, great songs, and Eric (Carmen) could sing with the best of them. Wish I could have done more of their records.”

Trio, Standard Time Vol. 1+2, Hot House Flowers, J Mood – Wynton Marsalis; Renaissance – Branford Marsalis

“Working with the Marsalis brothers was interesting to watch. You could see the family dynamic in action. Branford was always laid back, joking, ready to play basketball just as soon as his sax, willing to play with anybody. Wynton was very uptight at first; he seemed to feel like he had the future of jazz weighing on his shoulders and every little thing had to be perfect. Once I helped him solve his trumpet sound problem, he loosened up a lot more and we were able to knock out a number of records.”

The Singing Ranger, Vol. 3– Hank Snow

“I originally didn’t look forward to working on this record. I thought it would be old cowboy songs. Turns out this is like the beginning of rockabilly. Even George Thorogood did Hank Snow songs (“Move It On Over”). Had to clean up stuff, but the performances were great! Not what I expected.”

Destroyer – Kiss

“Had lots of fun working with Kiss. I also worked on “Beth”, that (drummer) Peter Criss ballad. Liked those big drum sounds in the 70’s like Bonham on the Zeppelin records. Later on, I got the chance to reproduce it on my own way. I brought a band into Studio A (at RCA Studios) and instead of keeping the drummer in the drum booth, I put the guitar and bass in there and brought the drums into the middle of the room. It’s big enough for a 60 piece orchestra, and the acoustic design in the wood and everything makes for a huge sound. Put a few mics back to capture the room and the drums sounded like cannons!”

Rest in Peace, Dennis.

Like industry legend John Curl in registration...PAYING to get in? Come ON! He's a national treasure!!

Like industry legend John Curl in registration...PAYING to get in? Come ON! He's a national treasure!! When it comes to audio shows, Charles Kirmuss's record cleaners are almost as ubiquitous as Lyn Stanley. Almost.

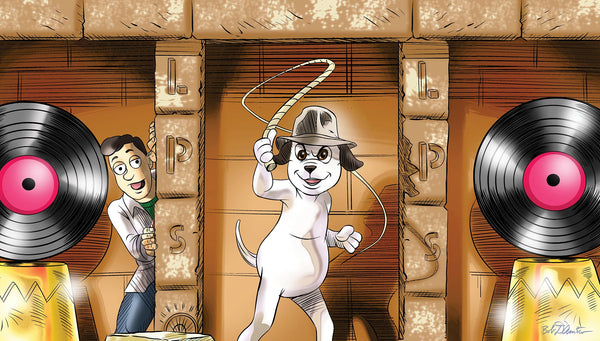

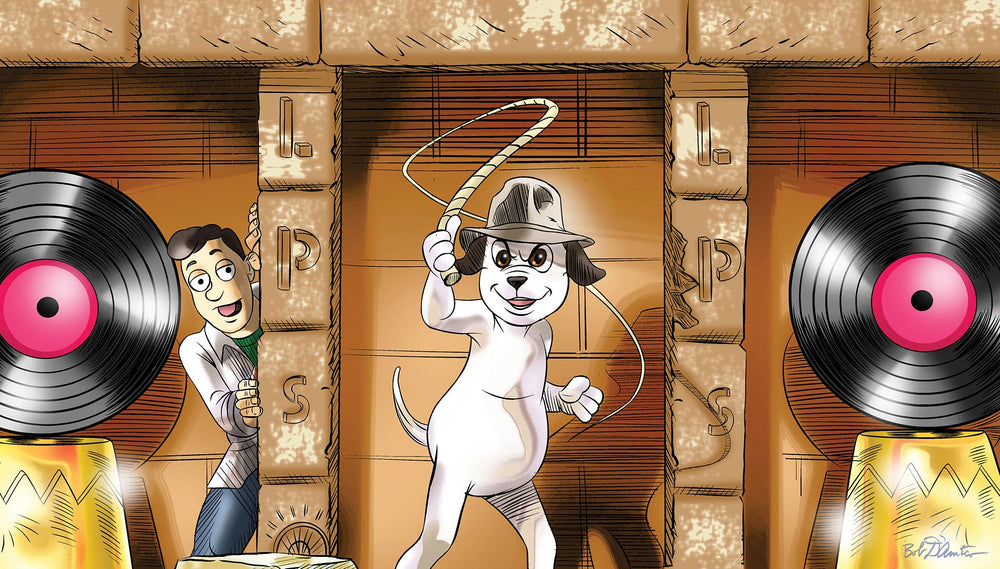

When it comes to audio shows, Charles Kirmuss's record cleaners are almost as ubiquitous as Lyn Stanley. Almost. Audio biz veteran Steve Holt was there again with LPs from his store, The Audio Nerd.

Audio biz veteran Steve Holt was there again with LPs from his store, The Audio Nerd. ...along with a youngish demographic, there was longtime vendor, Reference Recordings...

...along with a youngish demographic, there was longtime vendor, Reference Recordings...

Across the hall, Audio Federation had a familiar set-up with Audio Note UK driving big Acapella speakers with ionic tweeters. I'm fond of the Acapellas, but to my ears they needed more power and amps that provide a tighter grip.

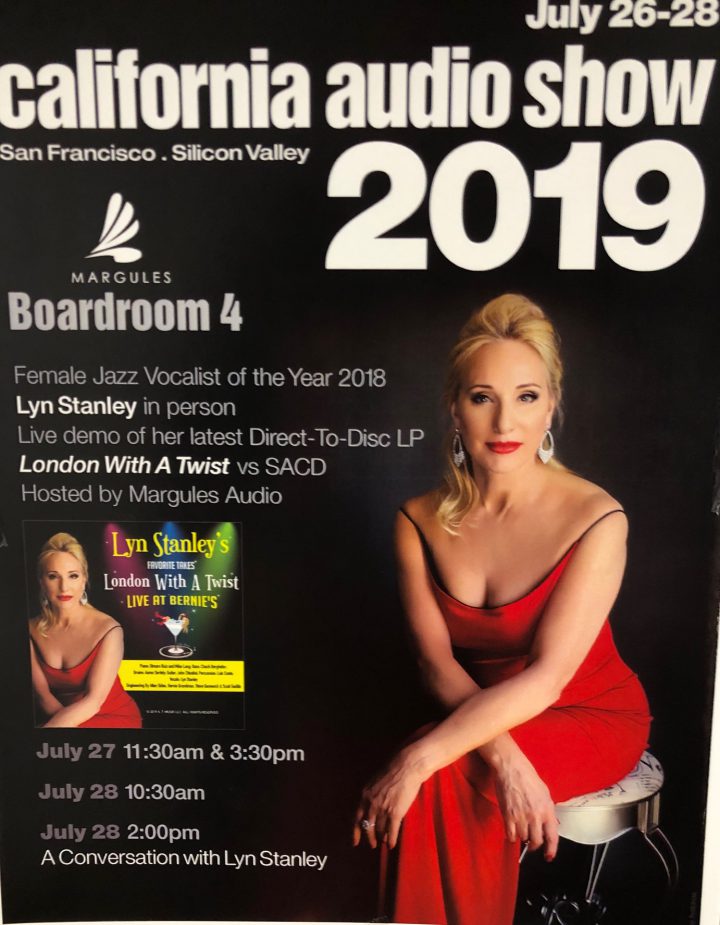

Across the hall, Audio Federation had a familiar set-up with Audio Note UK driving big Acapella speakers with ionic tweeters. I'm fond of the Acapellas, but to my ears they needed more power and amps that provide a tighter grip.  The Margules Audio room next door has generally been one of my favorites, featuring their own tube amps and multi-way speakers. Vintage Verve jazz recordings were reproduced with grace, space, and pace---as they used to say about Jaguars. There were also a few appearances by the she's-everywhere songbird Lyn Stanley, who discussed a recent recording. She may have sung, as well.

The Margules Audio room next door has generally been one of my favorites, featuring their own tube amps and multi-way speakers. Vintage Verve jazz recordings were reproduced with grace, space, and pace---as they used to say about Jaguars. There were also a few appearances by the she's-everywhere songbird Lyn Stanley, who discussed a recent recording. She may have sung, as well.

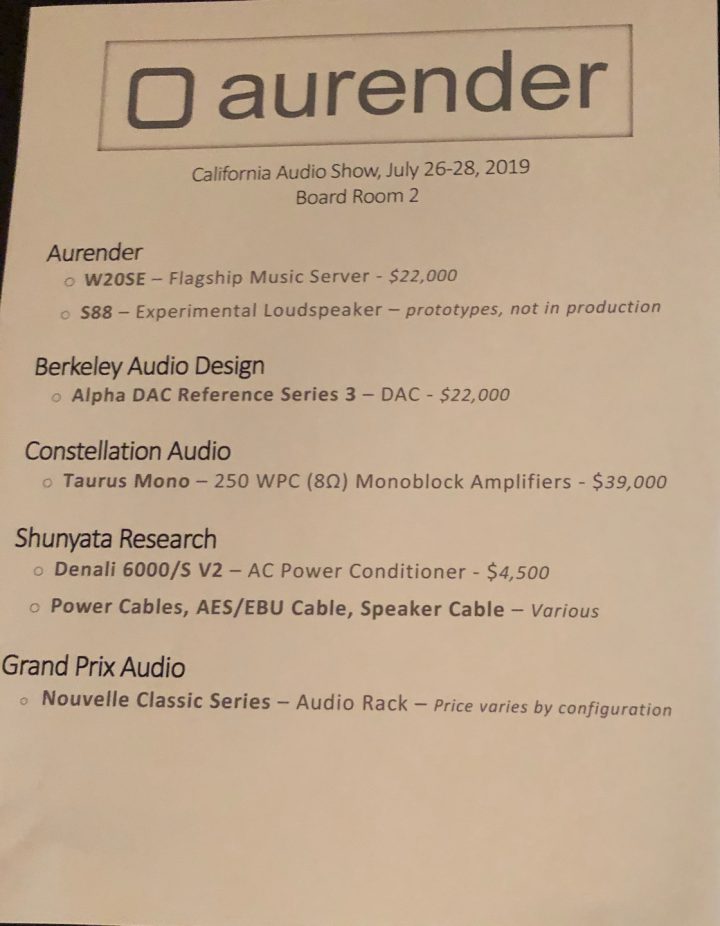

It came as no surprise that the Aurender room featured their top of the line W20SE server; what was a surprise was that the speakers were Aurender, as well. The prototype S88 speakers featured ceramic drivers, and paired with the big Berkeley DAC and Constellation amps, produced a civilized, polished sound with none of the nasties sometimes found in "projects".

It came as no surprise that the Aurender room featured their top of the line W20SE server; what was a surprise was that the speakers were Aurender, as well. The prototype S88 speakers featured ceramic drivers, and paired with the big Berkeley DAC and Constellation amps, produced a civilized, polished sound with none of the nasties sometimes found in "projects".

Pairings of Whammerdyne tube amps and Pure Audio Project speakers are always interesting, although the results have varied a great deal. The amps are all 2A3 based, one model single-ended, another features a pair of 2A3s in parallel in each channel. One interesting feature of the upper models is what the Whammer folks call "Remote Advanced Magnetics"---output transformers divorced from the main chassis, connected by umbilicals. The claimed benefits are lowered noise and EMI, allowing greater dynamic headroom. The Pure Audio speakers are all modular open-baffle designs, but the ones I've seen have ranged from tall 3-ways with horns and Heil AMTs (!), to 2-ways with cone drivers---and frankly, I'm not sure what all was in the "Classic" 15 speakers in this system. They didn't look like open baffles, and all that could be seen was the back of one driver in the rear of the cabinet. I didn't get the sense of power and ease that the best Whammer/PAP systems have provided in the past.

Pairings of Whammerdyne tube amps and Pure Audio Project speakers are always interesting, although the results have varied a great deal. The amps are all 2A3 based, one model single-ended, another features a pair of 2A3s in parallel in each channel. One interesting feature of the upper models is what the Whammer folks call "Remote Advanced Magnetics"---output transformers divorced from the main chassis, connected by umbilicals. The claimed benefits are lowered noise and EMI, allowing greater dynamic headroom. The Pure Audio speakers are all modular open-baffle designs, but the ones I've seen have ranged from tall 3-ways with horns and Heil AMTs (!), to 2-ways with cone drivers---and frankly, I'm not sure what all was in the "Classic" 15 speakers in this system. They didn't look like open baffles, and all that could be seen was the back of one driver in the rear of the cabinet. I didn't get the sense of power and ease that the best Whammer/PAP systems have provided in the past.

I've previously enjoyed Tidal speakers at CAS and elsewhere. This year I seemed to have become sensitized to a certain edginess in the Bricasti electronics heard in this system and two others. Combined with the too-big-for-the-room syndrome, I just didn't love this system the way I expected to.

I've previously enjoyed Tidal speakers at CAS and elsewhere. This year I seemed to have become sensitized to a certain edginess in the Bricasti electronics heard in this system and two others. Combined with the too-big-for-the-room syndrome, I just didn't love this system the way I expected to.  The modular casework of Wyred 4 Sound products is familiar, but like Aurender, the company had a surprise speaker. Like all the W4S products, the $6,000 TempuS speakers provided a lot for their price: a separate 12" woofer in a heavy ported cabinet formed the base, while the upper cabinet held dual 8" mids and 2 high-power ribbon tweeters with neodymium magnets. Total system cost was $25k, less than the cost of cables in several exhibit rooms. Sound quality was balanced, punchy, and enjoyable.

The modular casework of Wyred 4 Sound products is familiar, but like Aurender, the company had a surprise speaker. Like all the W4S products, the $6,000 TempuS speakers provided a lot for their price: a separate 12" woofer in a heavy ported cabinet formed the base, while the upper cabinet held dual 8" mids and 2 high-power ribbon tweeters with neodymium magnets. Total system cost was $25k, less than the cost of cables in several exhibit rooms. Sound quality was balanced, punchy, and enjoyable.

I had hoped that my second exposure to the peculiar Unisinger speakers---are they ashtrays? Fire extinguishers??---would provide a better impression than I received last year. It did not.

I had hoped that my second exposure to the peculiar Unisinger speakers---are they ashtrays? Fire extinguishers??---would provide a better impression than I received last year. It did not.  Fortunately, outside that sad little room I encountered Cookie Marenco, one of my favorite human beings on Earth. For the pic I forced her into a tight shot with another legendary recordist, Prof. Keith Johnson---who seemed delighted by the pose.

Fortunately, outside that sad little room I encountered Cookie Marenco, one of my favorite human beings on Earth. For the pic I forced her into a tight shot with another legendary recordist, Prof. Keith Johnson---who seemed delighted by the pose.  Wrapping up the first floor was a system consisting of server and DAC from new-to-me Musica Practica, with a Benchmark amp and speakers by Selah Audio. The server and DAC seemed promising, but ---whether it was the amp or the speakers, I couldn't be sure---the music seemed trapped inside the speaker cabinets. I stayed for several cuts to be sure, but things didn't improve

Wrapping up the first floor was a system consisting of server and DAC from new-to-me Musica Practica, with a Benchmark amp and speakers by Selah Audio. The server and DAC seemed promising, but ---whether it was the amp or the speakers, I couldn't be sure---the music seemed trapped inside the speaker cabinets. I stayed for several cuts to be sure, but things didn't improve  It was time to go outside and get a beer. Or several.

It was time to go outside and get a beer. Or several.