As 2021 entered the fourth quarter, the Audio Engineering Society (AES) held its annual fall show online in October, because of the pandemic still being in effect. Thankfully, the show seminars and interviews were recorded for on-demand viewing, so once again, attendees and reporters could still participate virtually.

Part One of Copper’s show report in Issue 151 covered analog electronic instrument design with Sequential Circuits’ Dave Smith, Line 6 co-founder Marcus Ryle and Akai MPC Renaissance designer Jennifer Hruska; and also spotlighted a symposium on the optimization of sound systems in all types of venues and configurations.

All About Stereo Panning

Hosted by Turkish composer, producer and audio engineer Ufuk Onen, All About Stereo Panning contained a look at modern DAW (digital audio workstation) features, such as stereo panning and stereo balancing – a significantly higher level of audio sophistication than simple monophonic left or right signal panning.

Onen defines the difference between stereo panning and stereo balance as follows:

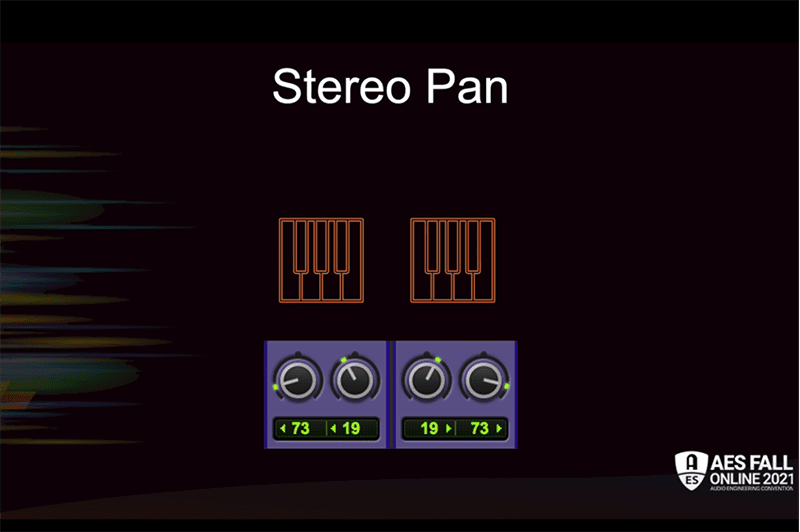

Stereo panning involves having the ability to independently pan a 2-channel stereo track to the left or right within the sound field panorama. Using a Pro Tools channel strip with independent stereo panning capability to demonstrate, Onen played the sound difference (best heard on headphones) between two stereo-output synthesizers, with each one panned hard left and hard right, respectively, and then he compared the sounds when the panning mix was not as extreme. He noted that left and right placement within the stereo field is often crucial for clarity and separation when mixing instruments of similar timbres playing in a similar register.

Stereo balance, on the other hand, does not change the position of the left and right channels. Stereo balance only affects channel levels. From a creative perspective, attenuating either the left or the right side of a stereo balance control can result in certain sound elements virtually disappearing from the soundfield, predicated on their stereo pan placements within the stereo balance environment.

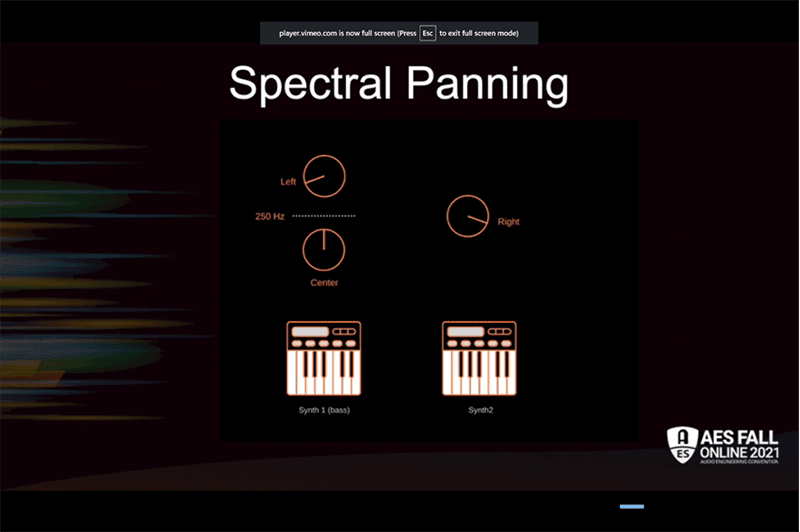

Onen explained how the creative use of panning when mixing can play with a listener’s sense of space. For example, he noted that low-frequency content tends to pull more attention and energy in the direction in which it is panned, much more so than with higher-frequency content. He explained that “spectral panning, which is frequency -based, is a tool that can be used to remedy this scenario if needed.

Spectral panning divides a signal into different frequency bands and then pans these bands separately within the soundfield. It is an excellent method for achieving balance and weight in a mix, without altering the sounds already placed within their pans across the stereo soundfield.

Utilizing spectral panning, Onen demonstrated how a mix with a low-frequency bass part played on a synthesizer panned left at eight o’clock obscured a higher-pitched part panned right at four o’clock. However, by taking the portion of the bass part at 250 Hz and below and panning it to the center, the sense of separation was maintained, yet the higher-pitched part cut through much more cleanly.

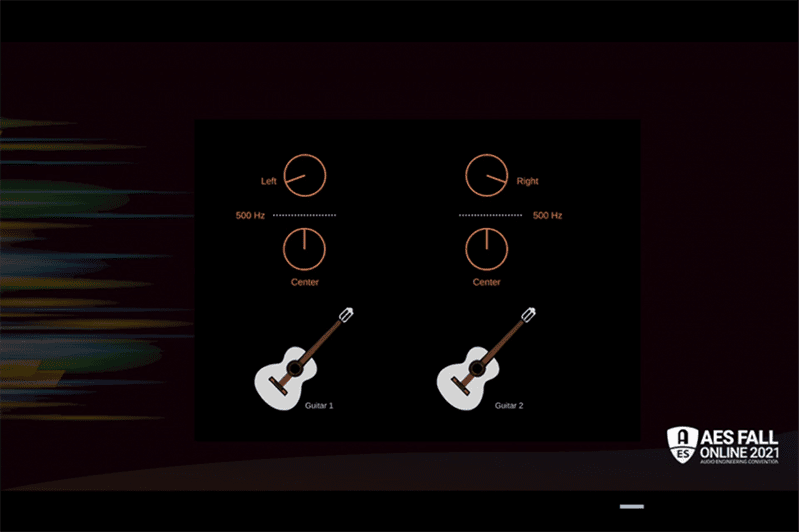

Another application of spectral panning that Onen demonstrated was with two similar instruments, in separating two guitars by panning their frequencies at 500 Hz and above to the left and right while keeping their lower frequencies panned to the center. The result was a more realistic and cleaner stereo image than would occur by having the two guitars in mono panned hard left and hard right.

Keeping the explanations and demonstrations on a fundamental level made this presentation especially useful for many independent DIY producers, engineers and musicians of varying levels of experience. Onen is to be commended for not succumbing to the temptation to show off more-complex audio considerations, something all too easy to accomplish with today’s DAWs.

Ufuk Onen.

Ufuk Onen.

Illustrations of spectral and stereo panning.

Illustrations of spectral and stereo panning.Keynote Speech From Producer Peter Asher

From his beginnings as a child actor in the UK, to pop success as a singer and guitarist with pop duo Peter and Gordon, to international fame and fortune as a Grammy Award-winning producer and manager for the likes of James Taylor and Linda Rondstadt, Peter Asher has had a storied career, and was a featured keynote speaker at AES Show Fall 2021. Reminiscing on his roots, Asher recounted that his mother was a noted classical oboe player, coincidentally teaching a young George Martin the rudiments of the oboe and music theory. His physician father was an amateur pianist and a huge fan of Gilbert and Sullivan. Early exposure to music in the Asher household was via 78 rpm records played on a windup gramophone with a huge horn speaker.

Peter Asher.

Peter Asher.Asher recalled that Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” was the first record he ever purchased and it was indicative of the fascination at the time with American culture by British teens. British record stores would offer the latest imported jazz, rock and roll and folk records, plus what would amount to “bootlegged” acetates of more obscure folk and blues music from artists like Woody Guthrie.

Intrigued by how records were made, Asher received both his first guitar and his first tape recorder in his teens. He jokingly noted that his early experiments included a primitive overdubbing technique achieved by using a piece of cardboard to block the erase head. Although the result was muffled, the young Asher was delighted that his attempts at adding a harmony vocal to his pre-recorded melody part actually worked.

The first exposure to stereo technology came to the UK commercially via BBC radio broadcasts. The left channel would broadcast on BBC radio while the right channel could be heard on the BBC television channel in a simulcast. Listeners were advised to place their radio six feet from their televisions and to tune into the station broadcast to listen to the test tone in order to perfectly balance it in the center of the stereo spectrum.

From orchestral performances to the left and right panning of moving trains and even the sounds from a ping pong match – all were enthralling, as stereo sound became a revelation to UK listeners, and Asher in particular.

A teenage Peter Asher with his first tape recorder.

A teenage Peter Asher with his first tape recorder.Asher’s early experiments with live recording included frequent visits to the famous Ronnie Scott’s nightclub, where he was allowed to record 20 minutes (one tape reel) of music when performers consented. Among the artists was Dudley Moore, who at the time was a professional jazz pianist, prior to his later breakthrough comedic success in TV and film.

Studying the liner notes of jazz releases by Rudy Van Gelder, Asher familiarized himself with the types of microphones used. It was at that time he learned of the Neumann U47 mic, which would come to serve him well in his multi-platinum projects later on with Linda Rondstadt.

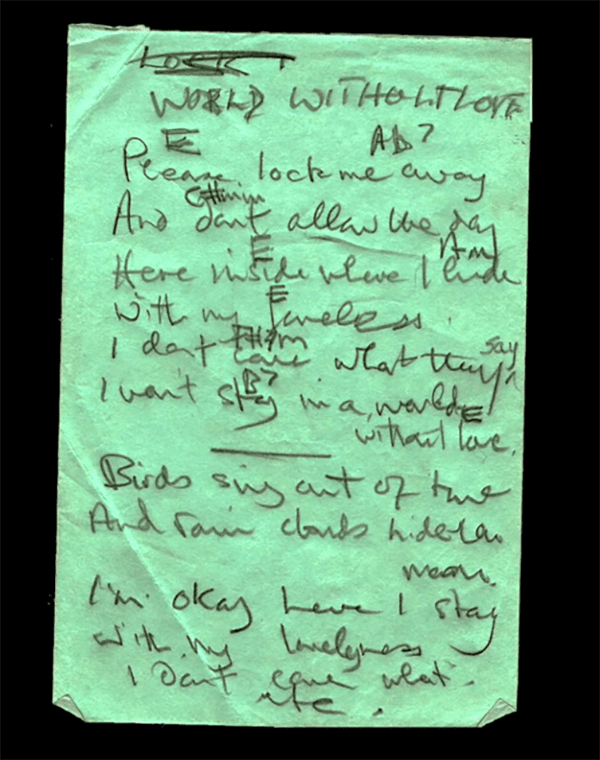

Asher recounted that his fortuitous meeting with Gordon Waller led to their duo, Peter and Gordon, building a reputation for themselves as a pub singing act and to a subsequent contract with EMI Records. He unabashedly explained the serendipity of his sister, Jane, dating Paul McCartney, resulting in the Asher family making a guest room available for the Beatle, who brought with him two Brenell tape recorders (with which Asher got to fully explore and perfect his overdubbing skills) as well as a bunch of original song fragments. One unfinished McCartney song that Lennon reputedly disliked intensely was “A World Without Love.” Once Asher confirmed that the Beatles had no intention of recording it, Paul graciously wrote out the two completed verses and recorded a rough demo of the opening verse and chorus on Asher’s tape recorder in his bedroom. Asher had kept this recording through the years, and played it for AES viewers.

As Peter and Gordon’s recording date for “A World Without Love” approached, Asher needed to go back to Paul to get the “middle eight,” or bridge, composed. In a half-envious, half-in-awe recollection, Asher states that a distracted and preoccupied McCartney went into a room and came back with the melody and lyrics for the bridge in only seven or eight minutes, composing a perfect part for the song with the same lack of attention to detail that one might take in writing a grocery list!

With song in hand, Peter and Gordon cut the record, and the rest, as they say, was history – a Number One hit in the UK, Europe and US. Asher recalled how they used a Neumann U67 mic set in a figure-8 pattern to capture their harmonized performance, and then double-tracked the vocals immediately afterwards. His affinity for LDC (large diaphragm condenser) mics in figure-8 patterns for duet vocals is something that Asher still uses today, with the theory that by singing into the same mic capsule, the vocals are “bound together” in a unique way, noting that John and Paul recorded many of their early Beatles’ vocal tracks using the same technique.

Captivated by the creative use of technology in the studio, Asher leaped at the chance to produce another artist when his friend, Paul Jones of Manfred Mann, asked Asher to produce his solo album. Asher assembled a killer band, featuring Jeff Beck (guitar) and Paul Samwell-Smith (bass) of the Yardbirds, session ace Nicky Hopkins (piano), and Paul McCartney on drums. This experience led to Asher being invited to head up A&R for Apple Records, resulting in Asher signing James Taylor for his first solo album and the start of an amazing track record of collaboration with hit records such as Sweet Baby James, Mud Slide Slim, JT and Flag.

Asher recounted how the repressive rules and regulations at Abbey Road, including its staff’s refusal to allow him the use of their new 8-track recorder for the James Taylor album, prompted him to cut the record at Trident Studios in Soho, London, where the studio happily let Asher use their then-new 8-track machine. McCartney’s contribution to Taylor’s “Something In the Way She Moves” on that album gave him a taste of the 8-track flexibility provided at Trident, which subsequently resulted in “Hey Jude” being recorded there.

Hardly nostalgic for the days of analog, Asher is a staunch fan of digital recording and wholeheartedly admits that he is happy to no longer have to deal with heavy reels of analog tape that sound duller after repeated playbacks, and having to physically edit tape using a razor.

Long a fan of Carole King’s songwriting, he became enamored of her piano playing and was thrilled to get her to play piano on Taylor’s Sweet Baby James. This led to her first solo performances at Taylor’s Troubadour Club performances as an opening act, and the premiere of the song “You’ve Got a Friend,” which was subsequently recorded by and became separate hits for both King and Taylor. They used the same musicians on both recordings: Lee Sklar (bass), Russ Kunkel (drums) and Danny Korchmar (guitar).

In his summation, Asher succinctly put the art of making records this way: “It’s about making it beautiful, emotionally real, and getting it right – and to never lose sight of the music itself.”

A Brenell open-reel deck from the 1960s.

A Brenell open-reel deck from the 1960s. Paul McCartney's handwritten lyrics for “A World Without Love.”

Paul McCartney's handwritten lyrics for “A World Without Love.”The Secret Life of Low Frequencies

The Secret Life of Low Frequencies was presented by Bruce Black, founder of Black Audio Devices and engineer at MediaRooms Technology LLC, Skywalker Sound, Dreamworks, and other post-production houses. The seminar recounted his history as an engineer and acoustic designer and his cumulative knowledge and exploits in creating acoustic spaces and rooms for a wide range of artists and producers in both the music and film/TV arenas.

The Secret Life of Low Frequencies was an hour-long, scholarly lecture about acoustics and physics with a number of practical and real-world tips, culled from Black’s extensive experience. While the lecture primarily addressed how to handle low frequencies within professional studios and critical listening environments, the principles also apply to personal listening spaces – something near and dear to the hearts of many Copper readers. Among Bruce Black’s insights:

- As low frequencies play a huge role in the perception of sound, whether for music, film, or other media, they are crucial for carrying dramatic weight and power, but can also ruin a listening experience if handled poorly or incorrectly.

- Sound transmission has two essential methods: by particle motion (high frequencies) and specular reflection (reflection off smooth surfaces), but it can also travel by pressure (low frequencies).

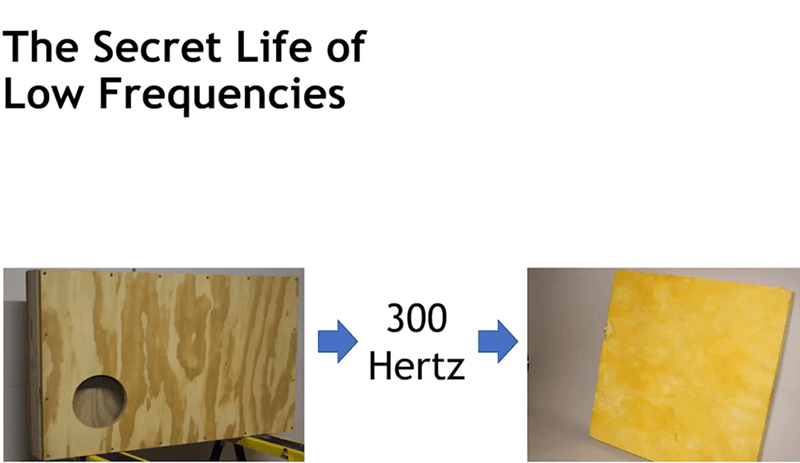

- 300 Hz, Also known as the “Schroeder Frequency,” is the demarcation line between particle motion and pressure-based sound transmission.

Black believes that insulation as an end-all for acoustical treatment is extremely limited, and that other remedies for various frequencies are required for an effective acoustic treatment protocol.

Resonance devices that respond to pressure reflections are the first step in those different remedies. Bearing in mind the 300 Hz dividing line, materials that are useful for particle motion can be considered differently from materials for pressure-based transmission.

Pressure absorbers, which will often have a bass port, will usually be closer to walls and other hard surfaces where sound energy gets displaced upon impact. As a result, using foam unilaterally, as some manufacturers might advertise, will inevitably lead to uneven and less than optimum outcomes.

Standing waves, or resonances, are the frequencies across the sound spectrum that are some of the hardest to handle – and Black pointed out that the majority of those are in the lower-frequency registers.

Pressure absorption baffle (with bass port) for frequencies below 300 Hz, and Corning fiberglass particle motion absorption material for frequencies above 300 Hz.

Pressure absorption baffle (with bass port) for frequencies below 300 Hz, and Corning fiberglass particle motion absorption material for frequencies above 300 Hz.

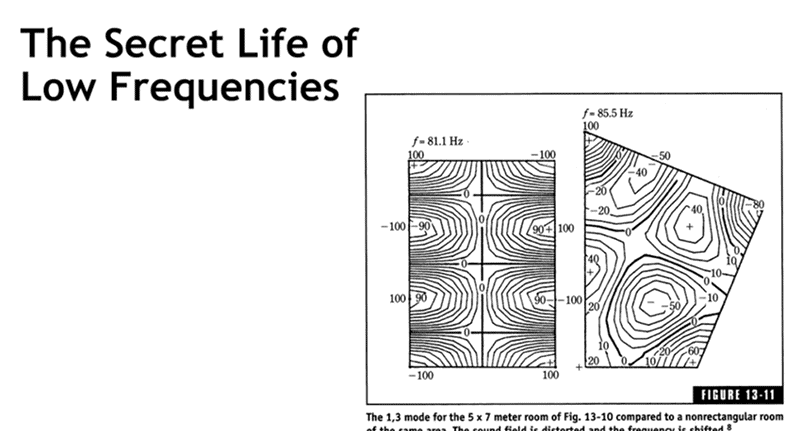

Non-parallel walls can cause resonances to frequency shift bounce back and forth erratically, making them harder to predict.

Black noted that there is no way to actually get rid of resonances. Controlling the spacing between room resonances, which is seldom taken into consideration when designing listening environments, is one of the most critical aspects, in his opinion, for getting a good acoustic room signature. Attainment of an even distribution of resonances in the frequency domain is key to obtaining a reliably good acoustic space without unusual colorations.

Calculating the dimensions of a room with the measured frequencies can generate a frequency graph that will give a visual indication of where the problems may lie and in what frequency ranges, so that proper remediation can be applied. This tedious process is repeated at different frequencies until the smoothest graph possible can be acquired.

Black also delved into consideration of construction materials, such as when drywall may react with certain low-frequency resonances to almost act like an additional speaker. Additionally, he looked at a number of other problems that may arise when attempting to design a listening environment.

Space limitations unfortunately deter further elaboration here, but Bruce Black’s insightful essays and articles have been published by AES, Mix, Recording magazine, The Cinema Audio Society Quarterly, and other publications,

Future coverage of AES Show Fall 2021 will include symposiums with cutting-edge producer-artist St. Vincent (Annie Clark), and platinum award-winning recording and mix engineers on the latest audio trends and challenges in the field, along with a look at seminars on audio mastering, archiving albums, and audio for cinema.

All images courtesy of the Audio Engineering Society.