In a previous article (Issue 158), we considered how it would possible to make meaningful adjustments to the in-room frequency response curve of our loudspeakers, by the use of a parametric EQ. We examined how we could find the frequencies we wanted to “edit” and which Q (or degree) of bandwidth we would want to adjust, using an analogy to f-stops in photography. (To recap: a parametric equalizer can adjust both the frequency range and the amount of peak or dip in the EQ curve applied.)

However, there are real-world limitations in what we can hope to achieve by making adjustments in the in-room response curve, so it seems like good idea to address what some of these limitations may be and why they exist in the way that they do.

One of the more common limitations that room correction software has, when used with a typical at-home speaker set up, is the expectation that with parametric EQ one should be able to make compensations for poor frequency response from the speaker itself. The reasoning may go something along the lines of, “I’m investing my money in high-quality room correction software and hardware in my A/V receiver (or preamp/processor), so I can save on putting more money into the speakers.” After all, the room correction software will offset the limitations of the speaker in the room because one can just boost the null points and trim off the peaks, right?

Although it is true you can boost some frequencies and cut others, the significance of having higher-quality rather than budget speakers in the first place cannot be underestimated. If you purchase lower-grade speakers with poor off-axis response and low sensitivity ratings, no amount of parametric (or graphic) can compensate for those limitations.

It’s true that a good parametric EQ will allow you to effectively boost and cut frequencies. However, keep in mind that it does this by increasing or decreasing them in the audio signal coming from the source material, before it gets to the speakers. The job of the parametric EQ is not really designed to compensate for the nulls that are a personality trait of your room/speaker interaction’s “frequency response.” If you have a huge dip in frequency at a given bandwidth, then no amount of boosting that null will really help to improve your sound. The null may well be a fundamental characteristic “suckout” of the room itself and simply trying to add more and more gain at that frequency could require more and more compensation than is healthy for a parametric EQ – and an amplifier – to provide. (Many software programs may allow you to boost or cut your dB by as much as 6 dB either way, which equates to a gigantic 12 dB range.)

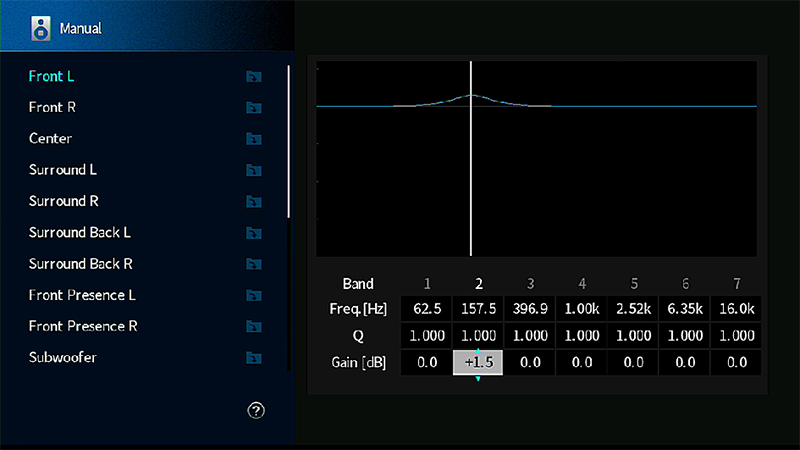

Yamaha on-screen parametric equalizer menu showing adjustment capability for frequency, bandwidth (Q) and dB.

If you have a huge null that is more than a nominal few dB to deal with, you might put extreme power demands on your amplifier’s power supply and/or subwoofer’s power amp stage, and you might also be forcing your loudspeakers’ (and/or subwoofer’s) bass drivers to operate with an excessive amount of excursion that will likely sound poor or even tax the voice coil drivers well beyond their design parameters. (If you’ve ever heard a woofer bottom out, it’s not a pretty sound!)

When making an edit to our frequency response curve using EQ, it should be best viewed as a means of refining or fine-tuning a system, rather than trying to coax your speakers to make “something out of nothing.” Also, be aware that for every edit you make in boosting or cutting your frequency response, you are literally distorting the original signal.

So, the thought is that, less is more when it comes to making these tweaks. And that’s what they really should be – tweaks, rather than great carvings or boosts to your sound. If you have run your room correction software correctly, it’s likely it will already have done some volume balancing for the levels of each speaker and/or channel. Sometimes, these can already be at a surprisingly severe dB level.

Returning to the use of parametric EQ: often the software (whether in an A/V receiver or preamp/processor or on a computer) will allow you to make greater adjustments than is healthy for your system and for your ears. For example, it’s unlikely you would want to make a 6 dB boost at a Q of 0.4 with a center frequency of 60 Hz, because this will produce such a wide bass boost across three octaves that it will mush out your sound and strain your drivers.

We’ve noted that adding in too many adjustments detract from the “pure” audio signal, and that trying to compensate for a severe low-frequency null in the room could tax your amplifier and speakers. But you could damage your tweeter if you try to flatten out its octave drop-off curve using EQ, by adding so much power back into the response curve that you destroy your tweeter (and maybe even midrange drivers) in the quest for a flatter high end frequency response. How is this even possible?

It is related to the fact that the measured frequency response of the room, and what you see plotted as a curved line (in room measurement software), is not what you actually hear, nor what is being produced by the speakers. Your tweeter, if it has extended high-frequency response, may produce sound at frequencies beyond what your measurement microphone will be able to pick up. (Some ultrasonic microphones are sensitive up to 40 kHz but often not highly accurate, due to limitations of their diaphragms.) Before you decry this as complete nonsensical idiocy, let’s take a step back and look at how the response curve is generated in the first place – and this is perhaps the most pertinent reason why some people will frown on room correction software altogether.

The room measurements are made with a microphone, which interprets the sound in a way that is not the same as the human ear(s). We have a pair of ears for one thing, not just one, and a highly interpolative sound-filtering and compiling brain. Also, some of you will have observed, that by moving the measurement microphone just very small distances left or right from the primary on-axis listening position, you will see that the response curve varies, sometimes wildly. It is for this reason (and no doubt many others) that many room-correction software programs have been improved over the years to encourage more localized sampling close to the primary listening seat, rather than processing a summative set of data obtained from radically different microphone placements throughout a room, such as in the corners or close to the back wall.

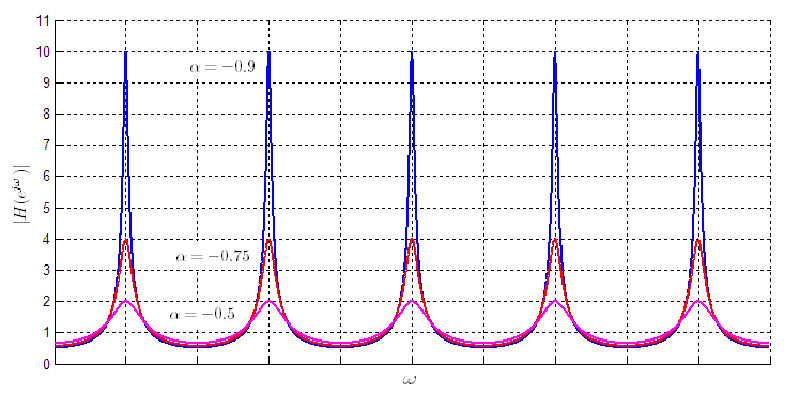

What about comb filtering? This occurs when a sound arrives at our ears, or microphone, with a very small delay between the signals. The result: dips and peaks at certain frequencies that are sharp enough to look like the teeth of a comb when seen graphically. In the case of our ears, sound arrives at each ear at slightly different times and is interpreted by the brain as a spatial cue. But if you measure a room’s response with a microphone placed in those radically different locations (as recommended in some historical room-correction setup software), the measurements can be subject to comb filtering, which affects the accuracy of the room correction. With more modern room correction, more localized samples are usually called for, as this is far more representative of what the listener may hear. (Comb filtering may be accommodated for to some extent, a subject which is beyond the scope of this article.)

You can see why it’s called comb filtering. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Oli Filth.

Returning to making effective EQ changes: if you follow the principle of keeping the adjustments minimal, you may well be surprised by how much improvement you can make to your sound that you can actually hear and enjoy, as opposed to applying an overly-heavily-modified response curve that looks like what should sound good, but whose disadvantages outweigh the theoretical sonic benefits.

******

Postscript: in a perhaps related area of interest, you might want to check out the Polk Legend L800 loudspeaker. It’s been designed to cancel out interaural crosstalk interference from each speaker, using a technology the company calls SDA, or Stereo Dimensional Array. In real life, your left ear hears what your right ear hears, but with a slight delay, and vice versa for the right ear. This provides vital locational cues. However, with stereo speakers, ideally only the left ear should hear the left speaker, and the right ear the right speaker: but this doesn’t happen. Both ears hear signals from both speakers – interaural crosstalk. The L800 employs dedicated stereo main driver arrays, and separate stereo cancellation arrays, which deliver interaural crosstalk cancellation signals to your ears. SDA is designed to create a wider stereo soundstage with highly focused imaging.

Polk Legend L800 loudspeakers.

Header image: graph showing parametric equalization. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Matias.Reccius.

0 comments