The development of modern stereophonic recording technique is generally credited to British engineer Alan Blumlein, who started experimenting with it during the first half of the 1930s, even though some earlier experiments by others had already taken place. The first stereo recordings were made possible by advancements in magnetic tape recording made during the Second World War by the Germans. Most of these early stereo recordings were destroyed during the War, and a few were taken by the occupying Russian army. Some of the earliest recordings that did survive have subsequently been commercially released in digital format.

The first commercial stereo recording was made by RCA in early 1954, followed shortly by Decca and most of the other major labels. At the time, the technology for producing stereophonic vinyl records had not yet been developed, and these early recordings were only available on magnetic tape. The first stereophonic vinyl record was released in 1957 by Audio Fidelity, probably the original “audiophile” record label. By the following year, most major labels were releasing stereo LPs, at a significant price premium to the monophonic versions that were sold alongside them. Upgrading to stereo at home involved significant expenditure, and many music lovers continued buying mono LPs until around 1969 when their production finally ceased.

Today, collecting monophonic-era recordings is a niche, but audiophiles should not overlook them. Admittedly, the early recordings on 78 rpm shellac, especially the acoustically-recorded discs (made before any electronic amplification was used), often sound very crude. However, some 78s can sound astonishingly alive, since many of these discs were recorded direct-to-disc and at what was a high speed, which many modern audiophiles recognize as the ultimate way to maximize the sound quality of an LP recording (higher disc-cutting speed can equate to better fidelity). Playing back these old shellac discs requires specialized equipment, since few modern turntables run at 78 rpm, and one also needs a 65µm spherical stylus and a preamplifier with all the equalization standards that were in use by the different record labels of the day. It is therefore easier to just concentrate on monophonic microgroove LPs, which first appeared in 1948. One potential problem is that prior to the stereo LP era, there was no standard equalization curve. In reality, many labels followed the RCA Victor New Orthophonic curve, which was eventually adopted by the music industry as the RIAA standard EQ curve by the time stereo LPs appeared.

The first commercial microgroove LP was a Nathan Milstein recording. He was the most popular classical music artist of the day.

Why collect monophonic LPs? For me, the music is the primary reason. The period between the two World Wars nurtured a large roster of outstanding artists, many of whom had direct relationships with the composers of the Romantic era. For example, Bruno Walter was Mahler’s protégé. Pierre Monteux played for Brahms, his mentor was a close friend of Hector Berlioz, and Monteux himself was a close friend of Stravinsky, Ravel, and Debussy. Unlike today’s artists, many of whom graduated from the same music schools and have been tutored by the same professors, the musical personality of these golden era artists was informed more by their experiences than by conventional pedagogic dogma, and there was more individuality and freedom of musical expression.

Some of the more extreme practices in those days would be frowned upon today as being inauthentic, but this does not make the interpretations any less valid. Toscanini was the first to publicly advocate strict adherence to the score as written, but he was not the only one. Someone once remarked to Pierre Monteux after a performance of The Rite of Spring that his tempo was different from that of one of the composer’s performances. Monteux replied: “Stravinsky can do what he likes, but I have to obey the composer’s wishes.” Stravinsky insisted on Monteux conducting the ballet’s premiere performance, in what turned out to be one of the most disastrous ballet performances ever. Critics laid the blame on the choreography, and Monteux stoically soldiered through to the end. The music has been associated with Monteux ever since, although he once confided that he did not much like the piece. Therefore, we can see that at least some conductors of the era chose to convey the wishes of the composer rather than their own ego. In any case, there was less emphasis on technical proficiency in those days, and more emphasis on musicianship, not that the top practitioners of the era were technically challenged in any way. The recordings from this era often give unique insights into the music that are simply not replicable. Unfortunately, many of these artists did not survive to the stereo era, and for those who did, they were no longer at the peak of their prowess.

There are sonic reasons for listening to mono recordings too. Early stereo recordings often suffer from the “hole in the center” problem, with the sound panned too far to the two sides. Mono recordings made with only one microphone tend to have a more solid and realistic center image due to lack of the phase anomalies associated with recordings made using multiple microphones. With single-mic recordings, track mixing was not necessary, thus reducing the number of stages during post-production that could degrade the quality of the signal. Recordings made during the mono era utilized tube electronics, which may or may not be an advantage depending on one’s point of view. Since almost all the electronics in my system are tube-based (except for the bass amplifier and the crossover), you know which camp I am in. I actually find listening to solo instrumental and vocal recordings in mono preferable to stereo. Many jazz fans also prefer mono Blue Note recordings over their stereo counterparts.

I estimate about one third of my LP collection to be mono. I had always listened to these recordings with a stereo cartridge, until last month. After having heard from different sources that playing mono LPs with a true mono cartridge can be a revelation, I decided to bite the bullet. Taking advantage of the historically low exchange rate of the Japanese Yen, I bought an Ikeda 9Mono cartridge. It has the exact same dimensions and weight as my current cartridge, the Ikeda 9TT, and almost the same output (about 2 dB higher). Therefore, by mounting it on the same model of headshell, I can just swap the cartridges on my SME 3012 tonearm without needing to make any adjustment.

The first record I reached for after completing the installation rituals was a 1952 recording of Elisabeth Schwarzkopf singing Schubert lieder with Edwin Fischer on piano. The first LP of this recording that I bought was the 1981 reissue on the French EMI Référence label when I was a student. It has become my desert island disc ever since. The young Schwarzkopf had a fresh voice and her interpretation was more free-spirited than her later performances. I subsequently bought two of the original Columbia 33CX Series LPs. Why two? It was because I found out that the cartridge mistracks on some of the more powerful high notes, which I suspected was due to groove damage. Many of these second-hand mono LPs have been played by their original owners using primitive equipment that caused groove damage. Since the LP cost literally pennies, I bought another one when I next came across it. Unfortunately, it had the same problem. In fact, the original LP was cut about 8 dB hotter than the 1981 reissue, at a level which would have been very difficult to track by the cartridges of the day.

Schubert Song Recital, original Columbia issue.

Schubert Lieder, later reissue of above.

Repeated mistracking is a frequent cause of groove damage. I then gave one of the 33CX LPs a quick wash in the ultrasonic cleaner before dropping the needle. The first thing I noticed was how much lower the background noise was. The Ikeda is a true mono cartridge and it only responds to horizontal movement of the stylus. Therefore, noise from vertical stylus displacement is absent. It also tracks better, since I believe the vertical compliance of the suspension is different from the stereo version. There was still slight distortion at times, but much less than with the stereo cartridge, and the LP has become much more listenable. The noise level of the older LP is still higher than the reissue, but I find the sound a bit more transparent.

Violin and cello recordings are my favorites, and I idolize many violinists and cellists that came of age during the interwar years. I came across a sale from a radio station during the early 1990s when I was still living in California. They must have been selling off their library of LPs after they had “upgraded” to “perfect sound forever.” I only found mono LPs in the bins, either because the stereo ones had already been sold, or that the station was selling these more valuable items to record dealers. Nevertheless, I picked up a good number of Capitol LPs featuring Nathan Milstein, along with Heifetz recordings on RCA, and Mercury LPs with János Starker. They were mostly in excellent condition, since they had probably only been played a few times right after acquisition before being filed away and forgotten.

I have subsequently purchased modern reissues of some of these recordings, with the belief that these newer LPs should sound superior. I decided to start re-listening with one of my favorites, a 1956 Capitol LP called Milstein Miniatures. After listening to just the first few seconds, I had already realized that the sound was remarkable. The violin tone is spot-on, the image is realistic, and one can easily follow the subtle nuances of the playing. A great-sounding recording has a way of grabbing your attention and directing it to the performance. The interpretations of the pieces are incomparable. Milstein’s playing is always so relaxed, unforced and totally unpretentious, moving the player out of the way of the music. The violin has a glowing sound, and the piano has weight and solidity.

Milstein Miniatures LP.

I then put on the 2018 reissue by a company called Analogphonic. The packaging of the record has been done well. They have reproduced the cover on thick laminated cardboard. The color tone of the picture at the front is different from the original, tending towards a purple hue. The record labels have been faithfully reproduced. The record is in 180-gram vinyl. This is clearly a product aimed at the audiophile. After the same few seconds, I have already noticed that the sound was different. The tone of the violin had changed, and it sounded harsher. The bowing seemed more aggressive. First impression was that it sounded more dynamic and detailed, but this was only an illusion. It was more fatiguing to listen to, and the sweetness of Milstein’s playing was no longer apparent. The Master was no longer relaxed and sounded quite uptight, as if he was trying too hard. The record was also cut 8 dB louder. The rest of the record sounded the same.

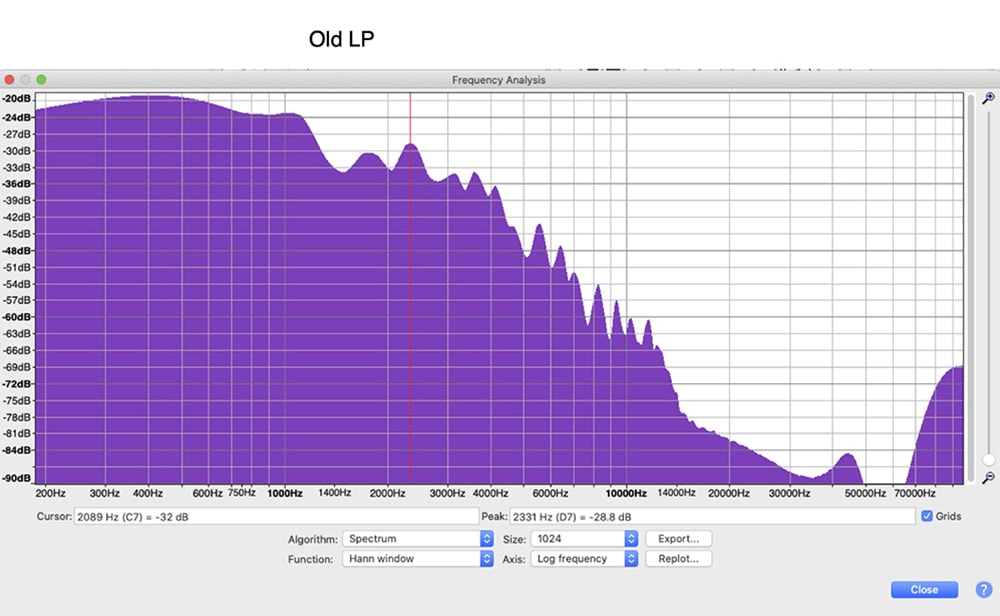

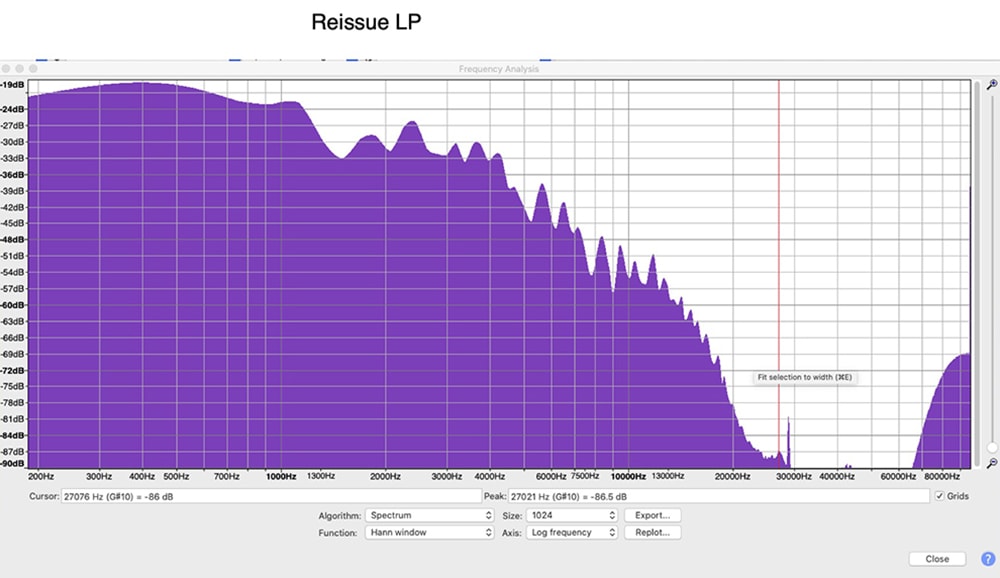

Intrigued, I transferred the first track of both LPs onto 24/192 PCM with my TASCAM digital recorder. I then did a spectrum analysis on the signal with Audacity software (available free of charge online). Both transfers were made at the same level. Analyzing the same 50-second segment of the piece, the spectral content of the music at 2 kHz, 4 kHz, 8 kHz, 12 kHz and 16 kHz in relation to 1 kHz is: original LP: -10 dB, -15 dB, -34 dB, -43 dB, -57 dB. The reissue LP measurements are: -8 dB, -10 dB, -28 dB, -31 dB, -55 dB. As can be seen, the reissue LP has significantly more high-frequency content; +5 dB at 4 kHz, +6 dB at 8 kHz, and +12 dB at 12 kHz compared to the original! Since I don’t have the master tape of this recording, I don’t know whether the original has too little high frequencies, or the reissue has too much. Judging by how the violin sounds in these records, I would guess the latter. I have found the same trend with many other modern reissues, so I guess boosting high frequencies is now an industry standard. Or maybe the mastering engineers are getting older and suffering from high-frequency hearing loss? Since I do have copies of the original master tapes of some other reissued LPs, I will be investigating this issue further in subsequent articles.

Spectrum analyses of the original versus reissue Milstein Miniatures LPs.

Header image: Milstein Vignettes by Nathan Milstein. All of the Milstein mono LPs in this article, and other, are worthwhile for both their music and sonics.

0 comments