- A cell phone was the size of a walkie talkie and cost over a thousand dollars a month, since you paid per minute for both receiving and making calls.

- 3/4-inch U-Matic and high-speed Betacam 1/2-inch video cassette formats were the indie professional workhorse choices for production.

- Multitrack recording on analog 24-track 2-inch tape was the industry standard.

- Macintosh computers had monochromatic (black and white) screen displays.

- People who worked in film and people who worked in TV/video were not only in separate camps, but had sufficiently dissimilar technical skill sets that they belonged to separate unions.

- The use of computer software for editing was still in its infancy, so video editing still was rendered sequentially on tape. Unlike today’s digital video editing where edited clips can be saved and randomly assembled (non-destructive), editing on videotape fixes the sequence of shots, and changes cannot be inserted without redoing the previous edits (destructive).

- Transfers of film to video were commonplace, but transfers of professional video to 35mm film were so rare that only two studios in the US had the technical know-how and equipment to execute it.

- Sony had created the F1 PCM stereo digital audio format to show off its technology in a consumer configuration that sounded so identical to its super-expensive professional system that the F1 and 501 tabletop consumer units became big sellers and Sony had to eventually scrap its pro system.

- Japanese musical instrument companies like Korg, Roland, Akai and Yamaha began marketing floppy disc-based digital sampling systems that were keyboard-triggered and available to working musicians, as opposed to the Synclavier and Fairlight systems used by people like Sting and Peter Gabriel that cost over $75,000.

A Sony PCM-501ES digital audio processor atop a Sony Super Betamax video cassette recorder. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Oliver A. Masciarotte.

A Sony PCM-501ES digital audio processor atop a Sony Super Betamax video cassette recorder. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Oliver A. Masciarotte.

Only a few years out of film school at the time, I had been working on independent films, music videos, and documentaries to gain experience. The mid-1980s was a fascinating time for audio and video production. Prices for equipment that used digital technology had finally reached the point where the hardware became affordable for independent production budgets. While film and video were still in rival and presumed never-the-twain-shall-meet camps (the notion boggles the mind in 2021!), digital audio had made great strides towards commercialization into the high tech audiophile and low budget professional markets.

Although this was before hard drive storage for digital audio had become practical and tape was still the medium of the day, the first use of video cassettes as a storage medium for digital audio emerged with Sony’s PCM-F1 Digital Recording Processor, which used the Pulse Code Modulation (PCM) format, and was also sold as a tabletop consumer adaptor unit branded as the 501 ES, a similar unit which was also licensed to Matsushita/Technics. The PCM-F1 converted analog audio into 16 bit/44.1 kHz digital audio, but stored it as a video signal which could be recorded on 3/4-inch U-Matic, Betacam or VHS video cassettes. The video tape, made to hold not only standard stereo audio but full spectrum color video, was considerably more convenient, robust and capable of storing the digital info as binary code than the Ampex 456 or other industry-standard audio tape at the time.

Additionally, MIDI samplers that could store sounds on floppy disks and could be keyboard-controlled became available at reasonable and even budget prices for the first time. The Akai S612, Korg DSS-1, Emu Emax and Roland S-10 were a few of the better models.

I had partnered up with a classmate, Dan Godzich, to form an entertainment company to produce independent film and video. We previously had shot a couple of student project feature-length videos on VHS equipment, and then produced a music video (ironically shot on 16mm film) for my band, Nekron 99. The music video, “Reincarnations,” was a quarter finalist in MTV’s The MTV Basement Tapes competition.

An opportunity arose for Dan to write and direct a feature film with a predominantly French cast, through family business connections. Our entertainment company was effectively acquired by a larger French company and we went into pre-production.

When it came to budgeting for sound, I discussed with Dan about using all of the new digital technology that was available and that if we could find the right post-production studio and engineers to work with us, we might be able to cut the sound budget without skimping on audio quality. Little did we know that the audacity of our inexperience would eventually lead us to achieve a small milestone in independent film sound in 1986.

Our theoretical rationale was:

- We had experience in dealing with SMPTE time code for video and film sync, which was required due to the differential in the frames per second rate for each format (24 fps for film vs. 30 fps for video), and we hypothesized that using analog 24-track 2-inch tape would yield higher sound quality and more mixing flexibility than if we used the 35mm mag track format more commonly used in film sound, a format which was much more expensive.

- If we were able to digitally record all of the sound effects and store them in a sample library, to then be keyboard-triggered for Foley (sound effects) work, this would again save us a considerable chunk of the sound budget without compromising quality.

- ADR (Automatic Dialog Replacement) would be required, since the film would have some actors speaking in French while others spoke in English, and those actors who were bi-lingual would be speaking both languages depending on with whom they were acting, and which language was more comfortable for the particular scene. The goal would be to have a complete English dialogue track, separate from a complete French dialogue track, with consistency of voices for each character.

- By using 24-track analog, we could mix down to 1-inch 8-track and have stereo dialogue, sound effects and music with an extra track for “wild” sounds and SMPTE for sync. (“Wild” sounds include crowd noises, wind, air conditioner rumble, or any other kind of background sounds that needed to be present for an entire shot.) This would then be transferred to separate optical tracks for international distribution, which would use the existing music and effects but then each region would hire their own actors to dub the dialogue in other languages.

While the tale of how the production money was raised and the guerilla methods we used to shoot the picture is a whole other story unto itself, suffice it to say that after we completed all photography, Dan sequestered himself in France to edit the film while I looked in New York for a place to handle all of the post-production sound requirements. The final edited online video cut, a compendium of footage shot mostly in high speed Betacam but also in 35mm film, would then be transferred to a 35mm negative in Los Angeles and then back to New York to Technicolor labs into a color-timed processed print for theatrical projection. (“Color-timed” refers to the film lab process of correcting the color when creating a fresh print from a negative.) We would then be taking a timecode video copy of the print to create the entire soundtrack.

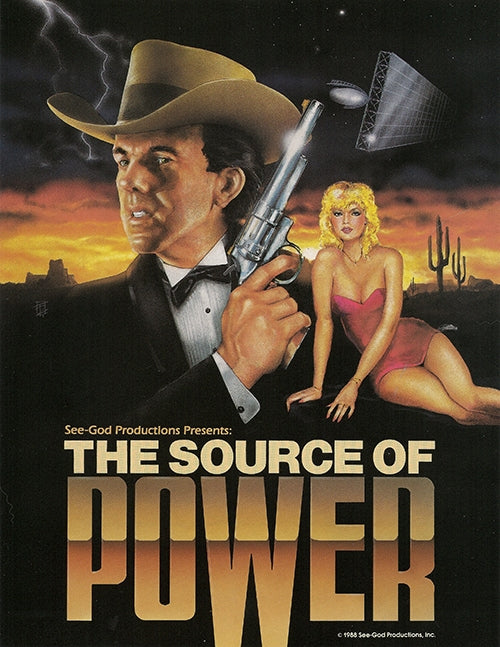

Promo poster for The Source of Power, the film John Seetoo and Dan Godzich created.

Promo poster for The Source of Power, the film John Seetoo and Dan Godzich created.The primary hurdle was finding a studio that understood what we planned to do and would be willing to work with us on what would be uncharted territory, since there was no guidebook or precedent for producing film sound using this type of inter-platform method, at least in New York City’s film and video production circles.

The one negotiating factor in our favor was that music recording and mixing studios at the time rarely dealt with feature films, and video work was confined to music videos. The budget we were prepared to spend was only perhaps 30 percent of what it would have cost to do it conventionally in a film sound facility at the time, but was a substantial amount of billable hours for a music recording studio.

After visiting over a dozen studios that either told us point blank that what we proposed was impossible or that they understood conceptually what we wanted to do but lacked the skills and knowledge to achieve our goals, we found Active Sound, a studio in Soho. The owners and engineers were former Right Track Studios veterans: Steve Tjaden and Carl Farrugia.

Steve had substantial experience working with computers and syncing with tape machines, lights, projections and video from his work with avant-garde performance artists and musicians, among them David Van Tieghem and Roma Baran (producer for Laurie Anderson). Carl was a former neighbor and apprentice of none other than Les Paul, the inventor of multi-track recording.

Active was a studio designed for electronic music production that utilized computers, sequencing, MIDI, and sampling, running off Mark of the Unicorn software. Although primarily consisting of a control room and a small alcove for overdubbing, it was perfect for our needs and in retrospect, was a forerunner for many studios today.

Active had a 24-track MCI JH24 recorder (critical since it could handle 14-inch reels, which would match a 20-minute film reel’s running time), a rebuilt Trident console, Yamaha NS-10 monitors, and a nice collection of outboard gear, such as LA-2A and dbx compressors, Pultec EQs, Lexicon delays and reverbs, an Ursa Major Space Station delay, and a collection of rack mounted Yamaha, Roland, Oberheim, Akai and Emu synths and samplers. They also had both U-matic and VHS storage for digital stereo mixdowns through a Sony PCM-501ES digital audio processor.

A Trident 24-channel console like the one John and Dan used in the production of the film. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/VACANT FEVER.

A Trident 24-channel console like the one John and Dan used in the production of the film. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/VACANT FEVER.

Most importantly, Steve and Carl were excited about the technical challenge and understood both the concept as well as the mechanics of how to pull it off, utilizing a TimeLine Lynx synchronizer to handle the SMPTE coordination between all of the machines. The fact that we would be block booking eight hours a day, five days a week for two months didn’t hurt either.

Looking back, we were fortunate to find Active. It was the only studio we met with who were willing to work on our terms and in our format. There was one other studio owner who understood what we wanted to do, but insisted that we rent his Synclavier for a separate daily fee for all of the digital sounds, which would require additional days of uploading, storage, and longer sessions, as he would be the only person allowed to touch it.

Having purchased our own Korg DSS-1 keyboard sampler and Sony PCM- 501ES processor, we had begun recording exclusive original sound for the film, essentially creating our own sound library, inclusive of Foley sounds. Every car door, footstep, splash, tree rustle, pratfall, car crash, gunshot…was created, recorded, and stored on a floppy disk or on VHS cassettes. Although we did have wild sound and location sound that we also used, we had no idea as to whether or not any sound might need to be augmented or replaced, and we didn’t want to audition third-party Foley and sound effects libraries, since Dan knew what he wanted and we had the means to get it ourselves.

With everything catalogued and finally ready to go, the studio soundtrack work was ready to begin.

Part Two of the story will appear in the next issue.

********

Trident Console

https://images.app.goo.gl/WQahufucX6NBZRUm6

Sony PCM 501 adaptor

0 comments