Loading...

Issue 87

Moscow

“Please list every single foreign trip you have taken.”

This was just one of numerous ridiculous questions on the Russian Visa application form.

Russia is the most bureaucratic place I have ever been to. To visit, you first need to get an invitation from a hotel. My Russian distributor had suggested that I stay at the hotel Ukraina, which, in those days, was far from a luxury hotel. After receipt of said invitation I filled in this multi-page form with too many questions and sent it off with my passport to the Russian consulate.

On arrival in Sheremetyevo Airport I waited in line for about 90 minutes to get through immigration. After acquiring copious stamps on my passport and hotel invitation, my distributor met me and whisked me off through the deep snow to the hotel. Russians drink an enormous amount of alcohol, so instead of bringing one bottle of Scotch Malt Whisky, I brought two. My distributor was pleased, as apparently bringing two bottles is the Russian way.

I had come to attend a Hi-Fi show in Moscow. It was April and with winter still hovering, Moscow’s snow was falling constantly. It was covered with a dirty brown dust caused by the burning of coal fires, which ultimately melted into brown slush. The town looked miserable. The grey sky and cheap housing reminded me (depressingly) of the Glasgow of my youth. The check-in at the hotel was also extremely long and I finally got to my room, which was long, narrow and overheated. The bed was concave and the furniture tired, but it did have a fabulous view of Moscow’s White House, which was famous for President Boris Yeltsin’s political standoff with the Russian parliament in 1993.

The Hi-Fi show itself was large and I don’t think I have ever seen so many brands in one place. At that time, Russian distributors were acquiring brands like crazy. Everyone was trying to one-up the other guy. I wandered around and joined in a conversation among colleagues who were comparing how much they paid for a taxi from the airport to downtown Moscow. Unsurprisingly, the prices ranged from $25 to $150.

One evening I was invited to a jazz concert in the Tchaikovsky Concert Hall. This hall, which is oval in shape with every row of seats higher than the one in front, has the most unbelievable acoustics. At one point the drummer left his drums and started to play the floor, the walls, the sides of his fellow musician’s instruments and about anything hittable. The sound was crystal clear. I would have loved to hear a classical concert there but it wasn’t to be. After the concert, I asked my host how I was getting back to my hotel. Moscow has a really efficient and fast subway system but there was no stop near my hotel.

“Let’s walk,” she said.

It was minus 20 degrees Celsius and snowing, so we walked. After about ten minutes she spotted a private car with its engine running.

“Let me ask him?”

A few minutes later she returned saying that he would drive us to my hotel for the equivalent of $30.

“Is that OK?”

“Sure,” I said as my nose, already blue, was solidifying.

The next morning I had arranged to meet Mike Creek from Creek Products for breakfast. I had told him where I would be staying and he decided to stay at the same hotel. We met at breakfast, which was massive with an incredible array of smoked fish, eggs, pickles, meats and breads. At the table next to us sat a young man with three really beautiful women hanging on his every word. They were scantily dressed and very drunk.

“Does your room smell?” Mike asked me.

“Smell of what?”

“Sweat, B.O., feet, death?”

“No, mine’s fine.”

“You’re lucky”.

After breakfast I went up to my room, breathed in the air and gagged. It smelled like a slaughterhouse in summer. My nose must have automatically shut down on arrival and Mike’s question woke it up. I wanted to change hotels but in those days your exit visa had to be stamped by the hotel that invited you, so I was stuck.

That day I tried to get some small change for a vending machine and as there was a bank in the hotel I entered, and asked the teller for change.

“Nyet!”

The front desk also refused to change my bills. Disdain for tourists was flourishing in this place.

I did do some tourist stuff. I saw Red Square and the Tsar’s jewels. The onion-domed churches were impressive. I also went to the GUM department store, which during Soviet times was the exclusive haunt of apparatchiks (high communist officials). Now it was an upmarket mall in a magnificent structure featuring brands like Armani and Prada. (Lenin must be gyrating in his glass tomb.)

That evening as I was alone and due to the weather unable to leave the hotel, I decided to eat in the hotel restaurant. After about 45 minutes of trying to get a waiter’s attention, I decided to take matters in hand. As a waiter passed me by, I stood up, blocked his way and shoved the menu in his face while pointing to a dish. I said,

“I want this.”

The startled waiter actually looked frightened and murmured something in Russian. It apparently worked, as I soon was served a very delicious meal of borscht followed by lamb kebabs with potatoes and tomatoes.

Seated at the periphery of the dining room were three or four of the most beautiful women I have ever seen. Long-limbed and blond, they seemed to have emerged from Vogue magazine. Every so often, a diner would approach one and after a short discussion, leave with her. She would subsequently return and resume her post. Her client would follow later and go straight to his seat. It took me a few moments to figure out what was transpiring. Security guards ringed the restaurant so I guess they were involved in the transactions. I have encountered prostitutes in many countries but these Russian women were in a league of their own.

I invited my distributor to a nightclub, which had good foods but was really noisy. My guests started to drink vodka as if it was water. I am not a fan of vodka but it did come in many flavors. My favorite was seasoned with pine nuts. Drinking vodka in Moscow with natives definitely enhances the taste but I learned the hard way that it is useless to try to keep up with these guys. I got so drunk I forgot to pay for the meal and they wouldn’t take my money the next day.

The byzantine bureaucracy, the feeling of being powerless and dependent on others to get around generated a surprising unease in me and for the first time in my life as a fearless traveler, I felt helpless.

The next day I left for home. Assuming correctly that it would take a long time, I allowed myself three hours at the airport. At first I could not find any check-in desks but after searching for a while I saw the Delta desk almost lost behind a long security line. Security cleared, I checked in, then proceeded to immigration which involved a 60-minute wait. My exit forms finally stamped and approved, I walked to my gate with about 15 minutes to spare. On arrival at JFK, the immigration officer asked where I had come from and I, the intrepid traveler, told him,

“Moscow; you have no idea how glad I am to be back in the USA.”

He smiled and said, “I hear this all the time.”

Everest

This year, so far at least, eleven people have died on Mount Everest, and most of us have seen the photograph of the ridiculous “traffic jam” of climbers in a long, long line snaking up to the summit. And all for the single reason that Everest is the tallest mountain on earth.

Everest has only been known for about 150 years. Although the peak itself was noted by a Chinese survey in 1715, it was not until the British “Great Trigonometric Survey of India” that measurements were made that would enable a figure to be put on its height. The survey itself is worthy of mention. Beginning at the southern tip of India in 1802, and using nothing more than giant purpose-built theodolites and triangulation, it took decades to plod its way up the country to the Himalayan foothills, mapping out every square inch along the way with extraordinary precision and accuracy.

It wasn’t until 1847 that the first observations of a certain ‘peak b’ were made by Andrew Waugh, the Surveyor General of India, from a distance of 140 miles. Back-of-an-envelope calculations suggested that this new peak might be higher than China’s Mount Kangchenjunga, at 28,169 feet the third highest mountain in the world, but at that time the highest known. Due to bad weather, it wasn’t until the 1849 season that further measurements could be pursued, and a series of five of them were made by James Nicholson, the closest being from a distance of 108 miles.

Nicholson calculated that the new peak, which by this time was officially designated ‘Peak XV’, was 30,200 feet tall, making it comfortably the tallest in the world. However, Nicholson was not able to take into account the known effects of refraction due to rarefied altitude, and so this result was known to be optimistic. The question was, how optimistic? Finally, in 1856, Waugh was able to make a proper calculation using Nicholson’s measurements and came up with an answer of precisely 29,000 feet. Feeling that such a nice round number would give an erroneous impression of being a rounded-up estimate, he arbitrarily amended his officially published figure to be 29,002 feet. It was said, therefore, that Waugh was “the first person to put two feet on Everest”!

There followed much discussion concerning the name to be given to what was now the tallest mountain in the world. Practice in the Survey was to preserve local names as much as possible, but at that time both Tibet and Nepal excluded foreigners from entering their countries, and Waugh could find no consensus among the local Indian population regarding a name for this peak. So he took it upon himself to name the highest mountain in the world after his illustrious predecessor as Surveyor General of India, Sir George Everest.

It is amusing to note that Sir George Everest pronounced his own name as “Eve Wrist”, and he would have been mortified to learn that his name would live on in immortality mispronounced – particularly since he originally objected to his name being chosen on the grounds that the local Indian population could neither write it in Hindi nor even pronounce it properly! Unfortunately, Everest, who at that time had long returned to England, never once set eyes upon the peak that continues to bear his name.

Everest is actually part of an outcrop of tightly connected ridges and peaks. It abuts Lhotse, which, at 27,940 feet, is itself the fourth highest mountain in the world. For those who wish to climb it, the challenge is not so much technical as physical. Acclimation to the extreme altitude is a major problem, particularly since that last 3,000 feet lie in what is known as the “death zone” above 26,000 feet.

If I can be forgiven for painting a complex picture in simple brush strokes, the death zone can best be viewed in the following way. When the human body undergoes exertion, in order to fuel these extra efforts the heart rate must increase to pump extra blood around, and while en route the blood picks up oxygen from the lungs, which it delivers to the cells that need it. However, there is a limit to how fast the heart can beat, and as we climb to higher and higher altitudes that upper limit reduces. At the same time, the resting heart rate is governed by the amount of oxygen in the air we breathe, and at higher altitudes the amount of oxygen decreases. So as we climb to higher altitudes, our resting heart rate increases. When we enter the death zone our rising “resting” heart rate, and our falling “maximum” heart rate meet in the same place. So, in effect, we cannot undertake to expend any effort because our hearts cannot beat any faster to provide the extra blood flow we need to power it. You will die, sooner rather than later, merely by staying in the death zone. You’ll have, at most, a few short days.

All sorts of problems occur when the human body ventures into Everest’s death zone, and all of them are potentially fatal. Conditions such as cerebral edema are particularly serious, and it is common practice, therefore, to use supplemental oxygen when climbing Everest, but the consequences of running out of oxygen are catastrophic, and you can’t haul spare cylinders in the death zone. Other conditions, like retinal hemorrhaging which causes loss of eyesight, can have practically fatal consequences at the top of Everest. It can be desperately cold on Everest, and hurricane-force winds are not uncommon – those of you who have not encountered the effects of a simple 30mph wind chill in a ‑30°C winter (a common occurrence every year here in Montreal) cannot have the first inkling of what that might mean. With the deadly combination of extreme cold and extreme altitude, rational judgment tends to desert you, which is not a good thing in the death zone. Many Everest climbers have died when they refused to turn around within a few hundred feet of the peak when their oxygen reached bingo level. They make the peak, they feel great, take a few photos, and pat themselves on the back. But they don’t survive the descent.

But if you are fit and healthy; if you take the time and effort to properly acclimate to extreme altitude; if you can survive the extreme cold; if you don’t suffer a cerebral edema or other medical emergency; if you are lucky with the weather; if you don’t run out of oxygen; and if you have joined a top-class climbing party and can afford the $50,000 or so that you’ll need to spend on it; then an ascent of Everest does not present too many technical challenges. Oh, and it also helps if you are at least partly insane.

Base camp is a comfortable 8-day trek from the normal departure point in the Nepalese village of Lukla, nestled half way up a steep mountainside, where, in the process of flying in, you will enjoy the most hair-raising landing in commercial aviation. Base camp itself is at 17,500 feet, which is seriously elevated. About 40,000 people a year make the trek from Lukla just to Everest Base camp, without any intention of going up the mountain. [This column just describes the ascent from the Nepalese side. There is another major route on the Tibetan side, but permits are harder to come by and there are other issues to contend with.]

At base camp you will devote several more days to altitude acclimation, which involves going part way up the mountain – often as far as the South Col to sample the “death zone” – and coming back down again. The route up the mountain from base camp begins with the ascent of the Khumbu Icefall, a huge glacier that moves about 3-6 feet a day, opening up treacherous chasms in which you could lose a modestly-sized skyscraper. Most of Icefall ascent will be spent criss-crossing those chasms using improvised bridges formed by aluminum ladders that have been pre-positioned each day by the Sherpas. You will be wearing huge and clumsy boots equipped with enormous ice-gripping spikes and holding tightly onto a rope. It is best not to look down. By the end of the first morning you will either become blazé or you will give up and go home. At the top of the Icefall is Camp I at 19,900 feet.

The next stage involves crossing the Western Cwm (rhymes with ‘doom’). This is a relatively flat expanse of ice, and the unexpected hazard here is heat. It is shielded on three sides by massive, steep valley sides, and is therefore sheltered from any cooling breezes. Most climbers want to strip down to their T-shirts. It is a long, hot walk up to Camp II at 21,300 feet, but it will seem like a stroll in the park after the appalling dangers of the Khumbu Icefall.

After two days of laboring up the glacier you will come to the Lhotse Face. It starts with an seemingly vertical wall of ice, several hundred feet high (it’s actually about a 45-50 degree slope), but then ‘levels out’ to a consistent 30 degrees leading eventually to the South Col. Climbing the Lhotse Face is not as technically challenging as it might sound, although what technique brings to the party is getting to the top without leaving yourself in a state of total exhaustion. Camp III (24,500 feet) is on a small ledge about half way up and is one of the most dangerous places on Everest, being routinely swept away by avalanches and falling rocks. But you will probably have to rest there overnight. You can then make your way up to the South Col, a remarkably flat piece of rocky ground with the highest mountain in the world rising above you on one side, and the fourth highest rising above you on the other. Hurricane-force winds regularly batter it, and the rocky surface has been blasted smooth by them.

Camp IV at the South Col is at 26,200 feet, 200 feet into the “death zone”. Being in the death zone is so bad that a full day’s rest can do more harm than good. So, having arrived totally exhausted, you will want to get at least some rest, but not too much. People have fallen asleep here and not woken up. Weather permitting, you will leave the South Col for your summit push not too long after midnight, and make your way up the mountain in total darkness. You will be in a state of total exhaustion. After each step you will have to pause and get your breath back. You must just focus on making your way up towards the summit, one step at a time. In reality it is little more challenging than a steep hike – apart from being in the death zone. Most of the climb is at comfortable 10-20 degree angles, with the occasional 50 degree section, plus one technical rock climb at the Hillary Step (not as challenging now as it used to be, thanks to the 2012 earthquake). But then it is a short stretch to the summit up a relatively gentle 10-20 degree slope, for which, on a clear day, you will require the very strongest of strong heads for heights.

A major problem with being in the death zone is that your mind can start playing tricks on you, and you probably won’t know that it’s happening. You can start to lose concentration, and your mind can dangerously wander. You can suddenly snap back to full consciousness and experience a moment of blind panic as you realize you have almost no recollection of the last 10 minutes with a 10,000 foot sheer drop on either side. You will come across dead bodies, some of which have been there for many years and have even acquired names as landmarks. But still you press on.

Depending on when you left, and how busy the mountain is, there will be a ‘bingo’ time, which is when you have to turn around because you only have enough oxygen to get you back to the South Col where, hopefully, your Sherpas will meet up with you with replacement tanks. [You can’t just leave them unattended at the South Col because someone will quite likely steal them. This is where paying extra – a lot extra – to participate as part of a high quality climbing team can start to really come into its own.] But when you reach that bingo moment, you have to turn round and descend. That can be hard to do when you are just a few hundred feet from the summit, in bright sunshine, and have spent six weeks of time and six months of salary getting this far. Also, those mind tricks can start to persuade you that it’s only 300 feet. How can it possibly take two hours to go 300 feet?

But if you are really, really lucky, you will make it all the way to the summit. At the summit you can take in a truly unique view that very, very few will ever get to experience for themselves. Hopefully there will be somebody to take a photo. You can bask in the satisfaction for an absolute maximum of 15 minutes – probably less – before you have to go back down, without forgetting that a disproportionate percentage of fatalities occur on the descent. It is like watching your team win the World Cup, but having to leave before the trophy is presented.

If all that still sounds cool, bear in mind that it makes no mention of the additional difficulties presented by the fact that there are now waaaaaay more climbers on the mountain than in any previous climbing seasons. It is exacerbated by the fact the peak is only really accessible during a narrow window in May of each year, and even then only during those days when the weather cooperates. During that window, Everest is beginning to look like Best Buy on Black Friday. This dangerous overcrowding brings about new and unforeseen hazards in an environment that is notably intolerant of unforeseen hazards. It will be interesting to see the final numbers for the 2019 season, but for 2018 it was reported that a scarcely believable 802 people summited Everest. So when you add to the mix of hazards crowds of people approaching that of the Donald Trump inauguration, I can foresee a time when a major disaster could – quite literally – take the lives of dozens – if not hundreds – of climbers. According to The Himalayan Database, as of the end of the 2017 season a total of 8,306 people have summited Everest, of whom 3,958 were Sherpas. And in total there have been 288 deaths, of which 115 have been Sherpas.

And in case you’re wondering – no, I’ve never been. I don’t have sufficient comfort with heights, which is a very significant prerequisite! I’ve been fascinated by Everest since reading Wade Davis’s exceptional book “Into The Silence”, an account of George Mallory and the three British expeditions to Everest in the early 1920’s, as well as Dan Simmons’ novel “The Abominable”, another epic read set in more or less the same time frame. But the hike to the base camp would be a bucket list item if my knees and hips weren’t falling apart. Interestingly, the entire route from Lukla Airport to Everest Base Camp can now be followed in exquisite detail on Google Street View!!! How long will it be before we’ll have the entire climb to the summit, I wonder?

Empire, Part 3

[Previous installments on Empire were in Copper #84 and #86—Ed.]

It’s ironic that I’ve ended up writing articles about audio history, as I always found school courses in history incredibly boring. The standard presentation was that of a linear narrative, like a simplistic novel: first A happened, then B, then C. The perspective was such that those chains of events seemed, in retrospect, inevitable; there was never any sense of tension or indications that things might have happened differently. In my experience, real life is full of subplots and tangled skeins of alternate paths, blind alleys, and dead ends.

Having now written dozens of these articles, I have a little more sympathy for those boring history textbooks. Without access to original source materials—diaries, letters, whatever—reliance upon public sources tends to yield a sanitized view of things, lacking in the turmoil and trauma of real life.

That’s a long way around of saying that this piece about Empire—a company that essentially ceased to exist over three decades ago, at least as an audio company— is similar to rote history, but with a few twists. I have at least some fragmentary insights into things that got messy, just the way they do in the stories of businesses like Sears and Gibson and Thiel.

So: I have a few facts, and I have spoken with some folks who were peripherally involved. Sadly, the major players are all long dead, and the printed record is the chipper, PR-glossed gee-whiz-bizspeak of audio mags from the ’50s through the ’70s. I’ll do the best I can at presenting what I know, and what I suspect…and I’ll try to make clear which is which.

In a recent interview, the great bass-player Jack Casady said of his interactions with Jimi Hendrix, “It’s never like writers think, or the way the great tidy eyes of hindsight would have it. As it’s going on, it’s a little more chaotic.” (You can read that full interview here. It’s worth your time.) I imagine that’s true of the retelling of any event, and I’m sure it was true of Empire’s story.

In our last installment, we looked at the Empire Grenadier line of speakers. Starting in 1964, the line ran with very few changes up to at least 1976—the last ads or mentions I could find. There were variants in finishes, and the late 9000 GT streamlined the end-table look a bit with simplified lines and an oh-so-’70s smoked glass top. If oldtime audiophiles recall the Grenadiers from the ’70s at all, it’s probably for a series of sexist 4-channel ads.

In 1971 with the dawn of Quadraphonic sound, both Empire phono cartridges and speakers were featured in ads with the heading, “Going 4channel?” The cartridge ads had innocuous photos of cartridges and their boxes. The Grenadier ads featured a single speaker at the center of the ad, with the sub-caption, “It’s no problem when they look like these…” and the speaker surrounded by 4 different poses of the same comely young brunette. In some magazines, she wore a t-shirt and shorts, barefoot; in other magazines she was nude–but coyly posed so that nothing censorable was exposed.

Different headline, no redaction.

To be fair, Empire was not the only audio company who ran cheesy cheesecake ads during that era, and compared to many ads from the ’50s featuring buxom babes in nighties or evening gowns, these ads were pretty tame. In spite of such ads—or because of them?— the company was better-known for its record-playing gear: the Troubador turntables, arms, and cartridges.

We all know that among all audio products, phono cartridges are probably the least sexy of all—that’s why they’re layered in exotic woods, semi-precious stones, yadda yadda. Compare this ad to the ones above:

1971, same year as ads above.

—Really makes you want to run out and buy one, doesn’t it? Be that as it may, Empire cartridges were highly-regarded during that period, said to have linear response, excellent separation producing a solid stereo (or quad) effect, with trackability that matched the best of the lightweight cartridges of the period. Even now there is demand for NOS Empire cartridges from the period—though the usual concerns apply regarding rubber parts hardening or becoming brittle.

About the same time as the cartridge above, the best-known variant of the Troubador turntable was introduced: model 598. The 598 was supposedly available with chrome-finished metalwork, but is generally seen with the gold-finished metalwork that made it stand apart from other turntables. Whether that finish is gaudy or stunning is a matter of taste; it certainly has a ’70s vibe, and would fit in with gents in plaid sportcoats and open collars and women in bell-bottomed pant suits.

At that time, record changers still dominated the US market, with brands like Garrard, Dual, and BSR dominating. Full manual single-play turntables were represented primarily by AR, Thorens, and the Empire—so it was part of a fairly elite group. The game-changing Technics SP-10 was a contemporary, introduced in 1970; the Linn Sondek didn’t appear until 1973, and was a fairly “underground” player in the US for several years. Between the 3 major manual players—AR, Thorens, and Empire— the AR was the affordable, mainstream model, produced by the hundreds of thousands; the Thorens models were sensible, austere, dripping with Swiss/German practicality; in comparison, the Empire seemed the choice of the Playboy bachelor pad.

The gold finish came off as yellowish in 2-color ads. Yeesh.

This is not to say that it didn’t feature solid engineering and decent manufacturing quality: the quiet and durability of the Papst hysteresis-synchronous motor and precision-ground main bearing and shaft are legendary, and each platter (2-piece in the 598, compared to previous 1-piece platters) was individually balanced. There are those who swear by the dynamic 990 tonarm, which set tracking weight with a spring—others swear at it, citing a certain clunkiness and easily-damaged, almost-irreplaceable headshell inserts. The 598 introduced the distinctive “doghouse” dustcover that would be a part of all subsequent Empire tables; panels of plexiglass were framed by wood.

During the period of 1970 through 1976, the Troubador evolved to the 598 II and 598 III. Most changes were minor, related to the 45 adapter, finish, and logo. The 598 III dropped the 78 rpm speed. Cartridges evolved along with the turntable and arm.

We’ve mentioned Empire President Herb Horowitz more than once in the course of this informal history. In 1970, Horowitz was elected Vice President of the trade organization, the Institute of High Fidelity; in 1972, he was elected President of the organization. Looking back today, IHF is largely remembered for its IPP—instantaneous peak power—power ratings for amplifiers, before RMS ratings became standard. I was once corrected when I characterized IPP ratings as “just before the amp bursts into flames”—the engineer I was chatting with said, “No—it was just as the amp burst into flames.” Sorry. (Yet another aside: I took a mail-order course from the IHF, and received a certificate as a “Certified Audio Consultant”. I think I was 16.)

More significant to our story, in 1975 Horowitz left Empire to become director of special projects for Harman International.

And here is where the history really begins to get fuzzy. I could find no mention in audio mags of the period of Horowitz’s successor at Empire, and folks associated with the company at that time, 44 years ago now—are either dead or untraceable.

The last mention I can find of the Grenadier speaker line was in 1976. That year saw the introduction of a new top model cartridge, the 2000z, still considered an excellent cartridge today. 1976 also saw the introduction of Empire’s last Troubador model, the 698. Its appearance was similar to the 598 series, but there were significant changes: a brand-new arm appeared, lighter in weight than the 990, and better able to maximize the extreme compliance of the new cartridges. A photocell-triggered end-of-play tonearm lift was also added, and through the years has proven to be unreliable and difficult to adjust. The plexiglass panels of the dustcover were replaced by tinted, tempered glass; the added weight of the glass often caused the always-troublesome dustcover hinges to fail even faster than before. Finally, the gold plating of the 698 seemed to be even more fragile than that of the 598—surviving units often show scuffing, wear-through, and corrosion of the underlying metal.

A glitzy 1976 ad for the 2000z cartridge. The gold body went along with the 698 turntable’s finish.

And now, a slight detour as we approach the final chapters of Empire.

Starting in 1965, Ernst Benz manufactured diamond styli and cantilever assemblies for phono cartridges in Switzerland. Over time, his business grew to where was was a supplier to Audio-Technica, Shure, Ortofon, Pickering, ADC, and Empire—basically, all the major cartridge manufacturers of the time. At its peak, the company employed 150, and produced 9 million needle assemblies per year.

In the December, 1990 Stereophile, Markus Sauer tells how Empire changed through increased involvement by Benz: “In 1981-82, he was approached by the owners of Empire….The owners, reaching retirement age, asked Benz, a major supplier, if he wanted to buy the company. Benz did. This, he says, was the worst mistake of his life. The factory he took over was old and not particularly efficient. Quality was mediocre because the worn-out machines could not be coaxed to work to close tolerances.” There are plenty of grisly details which I’ll spare you, but dividing time between Switzerland and the US took a toll on Benz’s business, and his OEM customers were not pleased that he was marketing finished consumer products that competed with them. Major clients, including Ortofon and Audio-Technica, let their contracts with Benz expire.

Back to Sauer: “…Benz had no choice but to close down Empire in the US and trim back his operations in Switzerland. His American adventure turned out to have cost him an awful lot of money. About the only thing that remains is the name, which Benz has kept for his Swiss company: Empire Scientific.”

As I mentioned in Part 1, the company where the hi-fi company Empire began as Audio Empire, Dyna-Empire, still exists as a precision machine shop. By 1961 the hi-fi division was simply called Empire; within the next year it split off from Dyna-Empire and became Empire Scientific. As we’ve seen, that company name ended up with Ernst Benz in Switzerland.

But it didn’t end there. At some point, Benz sold the name Empire Scientific to the English family back in New York. The family had, among other businesses, supplied replacement cartridge needles to record stores— at one time a big business. After the onset of CDs, the market for record-playing gear in general had a major decline, and the English family’s version of Empire Scientific branched out into the booming business of replacement batteries for camcorders and cameras. Over the years, replacement batteries for walkie-talkies and communications radios were added.

These days, Jeff English runs Empire Scientific. He’s the only connection to the Empire we know, and even his connection was peripheral and at the tail end of things. All stock, parts, and machinery from the hi-fi biz were long gone by the time he came along. Jeff mentioned a gentleman named Ken Bush as having been the head of Empire after Herb Horowitz’s departure, and a gentleman named John Agazon as running things after Benz’s purchase. I’ve been unable to find either person; if not dead, they’re no longer young. I wish I could be more certain of details, but it’s not possible.

Jeff English runs today’s version of Empire Scientific from Long Island, where the company once manufactured batteries. Not surprisingly, all manufacturing has gone overseas, and warehousing and shipping are in Tampa. About the only thing left from the hi-fi days is a version of Empire’s late “reversed R” logo.

What about Herb Horowitz? After leaving Empire, he got around. He worked at Harman from 1975 to ’77, and then joined Acoustic Research as an executive Vice President. My friend and colleague Lucette Nicoll worked for him, and designer/Copper contributor Ken Kantor worked at the company at the same time.

From AR, he became President of Rotel of America, then was a consultant to Cerwin-Vega, and then joined Ortofon US as an executive VP. His final jump was to Koss Corporation as VP for special projects. Herb Horowitz died in his sleep December 13, 1985.

The end of Empire the hi-fi company wasn’t pretty. In its day, however, the company produced products of integrity, many of which are still highly-regarded and sought-after today. There are worse fates.

[I want to mention once again the article “Some Empire Turntable History” from the AudioKarma website. It really is an invaluable resource for sorting out the confusing array of Empire models–-Ed.]

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Renovation

My current audio system consists of the following— and there is a reason that I’m telling you this:

Turntable: VPI Avenger Reference W/12” 3D printed VPI tonearm

Cartridges: Dynavector XV1-S/EAT No. 5

Phono preamp(s): Moon 810LP/EAT Glo S

Amp: Pass 250.8 stereo amp

Preamp: PS Audio BHK Signature

SACD Player: Marantz SA10

Power Regenerator: PS Audio P20 PowerPlant

Speakers: Wilson Sabrina

Record Cleaning Machine: Audio Desk System

Cables, interconnects and power cords: Nordost, PS Audio, Straightwire

The point of me telling you this is that I haven’t had this system to listen to since last November. I had to move while my apartment was being renovated, and put everything in storage.

Except for being away for long stretches on tour, I haven’t gone without some kind of reference system since I started out in this insane hobby in 1966.

I always had something to come home to.

In the early days I had AR 3a’s, KLH 6’s, JBL L100’s, Bose 901’s, OhmF’s…the list goes on and on and on…

The point is, I always could depend on great sound (at least at the times I’m referring to) in my living space.

When the architect told me that we needed to move out for 6 months I realized that everything had to go into storage. Not only that, but I was changing listening rooms in the newly renovated apartment, and quite possibly would have to downsize everything once I moved back in.

I packed it all up and had to figure out what I could bring with me.

The answer?

When I/we set up our temporary digs in an apartment building in Brighton Beach Brooklyn (28 train stops-1 hour and 20 minute subway ride from the Upper West Side of Manhattan), kindly loaned to me and my wife through a relative, there was no room to bring anything but our clothes…and our MoccaMaster coffee machine (sorry, but I had to draw a line in the sand!).

This apartment didn’t even have cable or a TV!

We brought in internet and cable to get through the experience…

Oh…and did I tell you that we moved into a Trump co-op building (Fred Trump built it in 1964) and it looked like a communist relocation center on the outside and a NYC high school on the inside…and it was located exactly between 2 elevated train lines with 4 train lines-the Q,F,D and N running by our window all day all night.

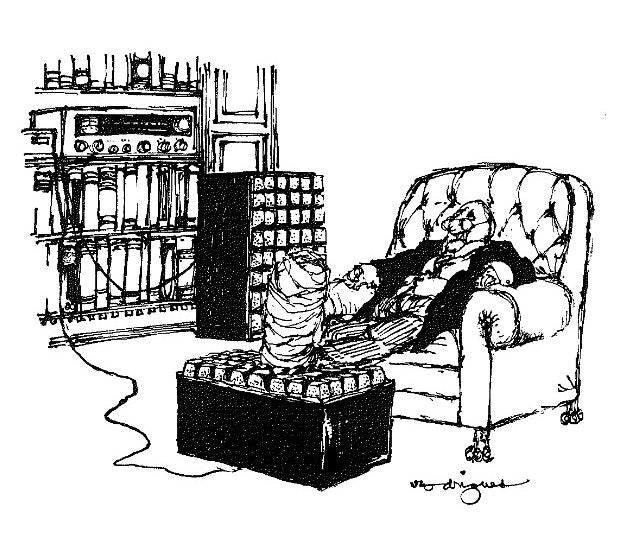

Sharon and the Trump building.

Oh yeah…did I mention that everyone is Russian in the building? The neighborhood is known as “Little Odessa”.

I should be happy about this right? Why? Because my family is from Odessa, but I have nothing in common with anyone in this building. The stores are Russian, the restaurants are Russian, the Chase Bank speaks Russian as a first language, and did I also tell you that we moved in in November. The building is 1 block from Coney Island which would be fine, I guess, if it was the summer but no, it was during this very cold winter and the wind blowing off the Atlantic Ocean made the boardwalk uninhabitable.

I really wasn’t surprised that on one particular February morning when the temperature was 4 degrees in Manhattan, it was -14 on the boardwalk but none of these older Russian tenants seemed to mind…why? Because it must have reminded them of Siberia!

And my audio system consisted of:

My Audioengine 2+2 self powered desktop computer speakers and a Bose mini sound bar.

That was it.

For 6 months. In other words, I learned how to “live without”.

Let’s get something straight:

I’m not crying about my lot in life: I’ve been pretty lucky.

I’m not whining either, except just to be funny…

But when I over-dramatically tell my friends who have known me for years and have always known me as the “guy in the neighborhood with the big stereo” that my audio system is a Bose Mini Sound Bar, they all gasp in horror and ask if I’m doing all right and can I survive this ordeal.

Kind of funny actually…

We moved back in and by the way, for those who have been renovated or are about to be let me tell you that our apartment was done on time and in budget.

None of those NYC horror stories and I just couldn’t wait to get back into the new apartment and get my system up and running…

Now I’m back but the room is smaller and so far I only can fit a pair of bookshelf speakers in it.

I think I will be able move things around to bring back the Sabrina’s but until then, luckily, I had a 35-year-old pair of Spendor LS3/5a’s lying around and hooked them up and I’ll tell you what…they never sounded so damn good!

Where I've Been, Part 1

If you’ve been interested (and I’m not saying you ought to be…), you’ll have noticed that for the last year, I’ve frequently been missing from these pixels, and Copper has rerun older pieces. I’ve been on—as we tend to call these sorts of things lately— a journey.

It began 16 years ago. I was impervious. I had been through psychedelic therapy several years earlier. I had scaled the mountaintops of my own being. And then, just past mid-2002, my phone rang: my very-hard-to-get-hold-of friend and guitarist Gregg called, asking if I’d heard about our great drummer friend, David. I knew right away that David was dead, his third heroin overdose.

As we talked, Gregg also told me that he’d been diagnosed with cancer. This was extraordinary and very bad news. And the type of cancer, I knew that it wasn’t good — it was exactly the same kind as took down my mother. And in January of 2003, he died. We had been a fantastic trio, Gregg, David, and me. Now I was the only one left.

On July 10 of 2003, for some reason, or no reason, I tried to push in on my abdomen. The left side went in, as normal; the right side was hard as a rock. Unmoving. I knew something was in there and had a very bad feeling about what it was. This would be a great irony: first David, then Gregg, and then me.

The next day was my wife’s birthday, and I kept my mouth shut, but the day after that I was in my doctor’s office. He acted like I was paranoid, saying he couldn’t palpate anything. But we’d get an ultrasound, and if it was at all inconclusive we’d get a CT scan. (Thanks, doc!) That’s when I told my wife.

The following Tuesday, I was laying on a bed getting an ultrasound. I saw the technician’s eyebrows go up. He asked if I had any trouble urinating, or whether I had seen any blood in my urine. I said “Kidney?” He said he wasn’t suppose to do what he was about to do, and turned the monitor so I could see: there was my right kidney, the upper-half looking normal, the bottom half looking like a large globe. It had a 13-cm tumor in it.

We began the process of interviewing doctors and figuring out who took insurance and who didn’t. We settled on the man who everyone told us was THE guy, despite the fact that he wouldn’t take insurance. He made us wait for two hours to see him; he spent 5 minutes with us. But, despite his rudeness, he gave us such confidence in him. He jabbed my abdomen with a pen, saying my scar is going to be like this, indicating an L shape on my gut. The surgery would take four hours, and would take four months to recover from. I would lose 2 units of blood. But he also said, and this might be why I’m writing all this, that a bout of kidney stones 6 or 7 years earlier had likely caused this.

I had known since I was 30 that my blood calcium measured high, and some years later had the theoretical cause confirmed: one of my parathyroid glands had been misbehaving for my entire life. (It would later be discovered to be in my chest, rather than where the other three were, on the thyroid gland in the neck.) The bad parathyroid likely resulted in kidney stones.

All through this time, I only felt fear for one hour: I suppose I might have been naïve, or somehow disconnected. Or maybe I AM that fearless. Who knows? But that hour came as we were waiting for results of a lung scan to see if the cancer had spread there. I can’t explain why, nor do I think it’s necessary, but the morning of July 31st, the morning of the surgery, I felt very light, optimistic and happy, joking around as I was being prepped. And then I was out.

I started waking up as I was being transferred from a gurney to a bed in the ICU, hearing a very large orderly talking about how much I struggled against him, and tried to tear out my “A” line, the IV tube that for some reason I was dependent on.

The next morning, still in the ICU, I could feel almost instantly when a nurse started mainlining me morphine: I started hallucinating grid patterns. My wife gave the nurse cookies and sweet-talked her into diluting the drug.

I learned after a few days what had happened after the surgery. The surgeon came into the waiting room, where my wife and friends were, in street clothes — two hours in, rather than four. My wife said she was about to launch into berating him for being what she thought was two hours late, when he said, “Well, I don’t know what happened, but I’m finished. I’ve been doing this surgery for 25 years and this was the most flawless one I’ve ever done; this guy has no fat on him. I wish I had cameras in the OR — this would have been the surgery to teach from. He lost less than half-a-cup of blood.”

And, sure enough, two months TO THE DAY (rather than the previously predicted four), I went out on my own to see Bernie Leadon perform.

Next: it gets more complicated.

THE Show 2019, Part 1

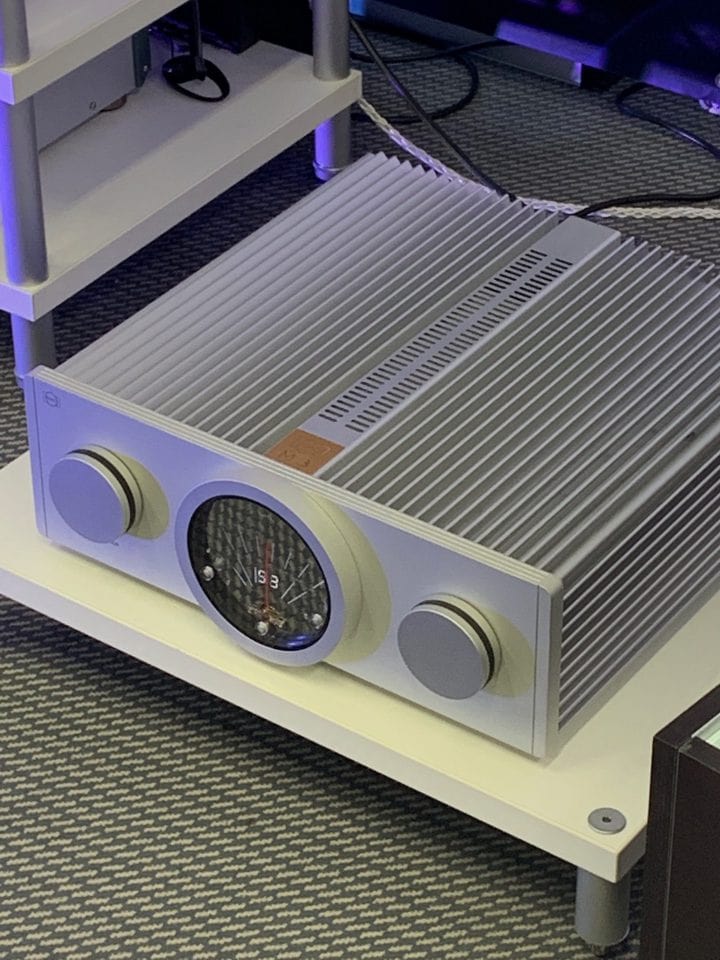

It was difficult to convince members of the San Diego Music and Audio Guild to attend the THE Show this year. [THE Show is a sorta-acronym, for “The Home Entertainment Show”. The name was devised before SEO was a priority; obviously, it’s a nightmare to Google—Ed.] That’s because the 2018 show was so small, it took only 1/2 day to see it all. Also, the drive through the SoCal morass to Long Beach is much further than Anaheim, site of last year’s show. But a few of us went anyway because Kyle Robertson, the Operations Manager, promised it would be much better than last year. I was still ambivalent, so I booked a cheap hotel room rather than one at THE Show hotel in case I decided to bail after day one. I needn’t have worried. THE Show was great. I’m told there were over 60 demo rooms. Even after two full days, we didn’t have time to do them all justice. Our first surprise on arrival was the easy freeway access off the 710. The very first right turn from the Ocean Blvd. exit is into the parking lot of the Long Beach Hilton — no endless drive through stop-and-go city traffic (that can seem longer than the freeway ride itself). THE Show organizers had arranged for an attendee parking discount. It was $18, but that’s better than the regular rate of $32. The people at THE Show’s registration desk were friendly, accommodating, and sufficient in number to avoid the traditional long line-ups. The hotel (bottom left in the header image) was clean and attractive, as one would expect at a Hilton, and the staff were pleasant and polite — not always the case in large hotels. The restaurants and bars of the waterfront area are within staggering distance, and the Queen Mary is not much further. Nice location. Detailed coverage of every demo room might be in the interests of the exhibitors, but it soon gets tiring for readers — so I’ll restrict my coverage to the demos I found most interesting. While we’re on the subject of horns, here’s a pair from Peter Noerbaek (shown) from PBN Audio in San Diego. The M!2 (how do you say that?) features twin 15″ JBL pro drivers and JBL’s latest studio waveguide system. It offered a surprisingly smooth top end and midrange with startling dynamics. As dynamics is one of the primary distinctions between live and reproduced sound — evident even in the next room or down the street — it’s great to hear a sound system do it so well. The electronics are all PBN also. I’ve been to the PBN factory and the quality of construction of everything made there is impressive. In my opinion, directional speakers like horns tend to sound better in small hotel rooms because they don’t splash high and mid frequencies around like a fragment grenade — which results in a shower of (out-of-phase) reflected sound. ($30,000/pr.) This 3-way Monterey horn system from Ocean Way Sound was designed by Alan Sides, a 5 time Grammy award winning music producer who owns 5 recording studios across the country. His California-based company is the hardware offshoot of Ocean Way Studios. For $22,000/pr, the sound was impeccable. The powered, stand-mount Pro2A monitors impressed me with their dynamics, neutral tonal balance, and unbelievable bass. They were so dramatic, I wasn’t sure which system was playing when I walked in the room. Neither were many of the other attendees. These speakers are readily available from places like the Guitar Center for under $4000/pr. Seems like a great way to get audiophile sound for those under the constraints of room size and budget. Although the ‘AGD Productions’ amps in this system look like SETs, they are actually MOSFET power amps producing 200 watts (into 4 ohms). Here’s a good look at one of their illuminated Gallium Nitride tubes, which don’t feature a vacuum. Back to the future. These speakers look a lot like the Altec Lansing A7 “Voice of the Theater” models produced over half a century ago. That’s because they are. The drivers were refurbished, the cabinet volume was enlarged to 9 cu. ft., the ports were mirror-imaged, and the cross-overs were re-engineered with modern components and testing procedures. The result: the best of what these vintage speakers have to offer with few of the traditional flaws. The transient response of the horns remains excitingly dynamic, but they no longer tear your ears off above Muzak levels. The bass units offer superior resolution, but without the irritating room modes excited by subwoofer frequencies. Their manufacturer provided no business name, but he’s located in Carlsbad, CA and can be reached at sudz99@yahoo.com ($10,000/pr.)

Back to the future. These speakers look a lot like the Altec Lansing A7 “Voice of the Theater” models produced over half a century ago. That’s because they are. The drivers were refurbished, the cabinet volume was enlarged to 9 cu. ft., the ports were mirror-imaged, and the cross-overs were re-engineered with modern components and testing procedures. The result: the best of what these vintage speakers have to offer with few of the traditional flaws. The transient response of the horns remains excitingly dynamic, but they no longer tear your ears off above Muzak levels. The bass units offer superior resolution, but without the irritating room modes excited by subwoofer frequencies. Their manufacturer provided no business name, but he’s located in Carlsbad, CA and can be reached at sudz99@yahoo.com ($10,000/pr.)  These Tune Audio speakers ($58,000/pr.) were built in Greece and are distributed by Turks. That in itself impressed me. If these two groups can get along, maybe there’s hope for America. The larger horns are machined from many layers of wood and make a striking visual statement. Their dynamics were stunning and I didn’t hear the traditional honk on the music played with Wavac electronics. The gorgeous cabinets also serve as horns for the down-facing woofers, which are located at the top.

These Tune Audio speakers ($58,000/pr.) were built in Greece and are distributed by Turks. That in itself impressed me. If these two groups can get along, maybe there’s hope for America. The larger horns are machined from many layers of wood and make a striking visual statement. Their dynamics were stunning and I didn’t hear the traditional honk on the music played with Wavac electronics. The gorgeous cabinets also serve as horns for the down-facing woofers, which are located at the top.

The Sanders Model 10E speakers are the most highly resolving speakers I’ve ever heard. But only in the prime listening position because they are also the most directional. This is a blessing for those whose sound room doubles as a living room because the sound attenuates quickly off axis. This feature makes them less than ideal for multi-seat home theaters as they are not intended to be room fillers. Uncharacteristically for panels, they produce sparkling dynamics, even at high volumes. The tonal balance is so neutral, they’d make great studio monitors. As a result, they sound wonderful on almost every type of music. Despite their size, they have minimal visual impact due to the see-through nature of the panels. They retail for $17,000 including a Magtech Amplifier and an LMS loudspeaker management system. That includes a digital crossover, room correction, digital signal processor, and real time analyzer. This is a system for uncompromising perfectionists.

It was nice to see more young people than I usually notice at audio events. [Part 2 of Jan Montana’s report will appear in Copper #88—Ed.]

Django, Act 2

[Act 1 of the Django Reinhardt story appeared in Copper #86.]

The Manouche poultices and remedies had kept Django alive but his mother Negros realized he was not recovering. Negros and friends took DJ back to the Hospital Saint-Louis. Reinhardt’s burns began to heal and the doctors saved his leg.

The left hand was partially paralyzed, the skin burned off and the muscles, tendons and nerves were in such deteriorated condition it was believed he would never use the hand again. But the doctor had a private clinic where he thought he could treat Django. This was going to cost. Negros and Pan Mayer, the father of Bella, the wife who would leave Django, hocked everything they owned and on DJ’s 19th birthday he was admitted to the clinic in hopes of operating on and saving that left hand.

After the surgery Django was transferred back to the Hospital Saint-Louis to convalesce. Negros went to his bedside every day and had to be sent out after visiting hours each night. She tended to DJ and never really trusted the doctors to take care of him. As Django improved she had his brother Joseph, affectionately known as Nin-Nin, purchase a new guitar and bring it to his thoroughly despondent best friend.

Saved his life. Mom.

Django began the excruciating and mind-numbing process of getting his hand to play the guitar again. For months in his hospital bed, he willed his index and middle fingers to work. The ring and pinky fingers were basically useless. The index and middle fingers began to move slowly through scales but DJ had to develop a new fretboard style going up and down the neck compared to traditional guitarists that use the ‘box of notes’ technique where the player stays in one or two positions going through the scales. Django had come up with a method where he played with two fingers up and down the neck. This method is still recommended for guitarists, that they learn in one or two positions in the traditional manner but also work the scales on one or two strings up and down the fretboard. DJ also had to reinvent chord patterns. He used the two fingers to find alternate triads using open notes when he could and sometimes jamming the crippled pinky on the ‘E’ string and the deformed ring finger on the ‘B’ to help him with more complex chords. Really?

There was no one to show him this. He was on his own.

After 6 months of this slavery in the hospital two of his fingers came back to life and old melodies returned. In early 1930 he joined his fellow Manouche, still walking with crutches and his hand wrapped to hide the scarring, back at the caravans for a family festival. Once the traditional meal featuring the Romani delicacy hedgehog (you heard me) was finished, everyone settled around the campfire and the instruments came out. Django went inside Negro’s caravan to retrieve his guitar. He was probably watched with pity but admiration for his guts as he un-wrapped his hand to play and everyone saw the condition of that hand. Surely no one expected much.

He joined in the song, keeping up using his new chord techniques. At one point he took off into a solo that astonished everyone, with flourishes and fretting speed none of them could do with four fingers let alone two, Negros beaming with pride. Everyone present related to their deaths they had witnessed a true miracle that day. The legend of Django Reinhardt was re-born.

As I mentioned in the last column Django’s wife Bella left him within months after the fire and remarried. What I didn’t talk about was Django’s first wife Naguine. Yes, by 18 Django had been married twice. His first love Naguine he married at 15. The traditional marriage rites were different in the Manouche caravan community. When a couple went off on their own and came back after a few weeks they were considered a married couple. No muss, no fuss, just fact. This must have saved a ton on wedding parties. I tried to talk each one of my kids into this but Diana would have none of it. Anyway, later he met the beautiful Bella and he dumped Naguine and ‘married’ Bella. Naguine was hopeless and took to the road to get away from the memories and the families settled in their caravans on the outskirts of Paris.

On a spring day in 1930 Django left the Hospital Saint-Louis for the last time leaning on the arm of Negros. Waiting on the sidewalk was Naguine. She had heard of his tragedy and returned from Tuscany to search for him. She handed Django a bouquet of tulips saying “Here! These are real and won’t start a fire.” Zing. And so a new love affair bloomed, one that would last longer than the first.

Reinhardt could have gotten a job in the bals musette with any accordionist doing the traditional material, but he had become completely blown away by the jazz of the likes of Billy Arnold and Louis Armstrong. He and Nin-Nin once again took to the streets of Paris to play for sous but working on jazz tunes.

In 1931 Django and Naguine walked from Paris to Nice in search of work. A distance of 520 miles today on modern roads. They were broke and without a guitar because he’d lost it in a poker game. The only work that could be gotten were odd jobs along the way. Without that guitar Django couldn’t find any credible work in Nice so they moved on to Cannes where he somehow got an instrument and a job at the nightclub Banco. Headlining at the Banco was an American violinist with his own band. Eddie South.

South was born in Missouri in 1904 and early on studied classical violin. Eddie was a prodigy so his parents moved to Chicago to enroll him in the College of Music. But South was black, and in the 20’s there were no chairs for black musicians in formal orchestras. Like his compatriots in color he switched to jazz. However, Eddie never lost his interest in classical music. A move had to be made.

South resumed his classical studies in 1929 by moving to Paris and then Hungary. It was during these travels he came across the playing of the Manouche Romani violinists and he incorporated the sound in his jazz compositions. Django first heard this sound when alternating sets with Eddie at the Banco. Reinhardt was awestruck and would never forget the sound.

In 1937 these two recorded together and you can hear what Django would have heard in 1931. This is Django and Eddie South doing “Eddie’s Blues”.

During 1932 to 1934 Django started playing for Jean Sablon, a French Bing Crosby who had some popularity and his own orchestra. DJ also alternated with Louis Vola’s band and renewed his old professional relationship with the Italian accordionist Vetese Guerino with whom he’d played before his accident. Django was two steps above the life of a hedgehog, horribly irresponsible with money and gigs, incapable of any personal grooming and basically starving. DJ would eventually cast quite a dashing figure as his ego realized the possibilities of looking good, but in those days he barely bathed.

It was Vola and Sablon who began working with Django to not only force him to get to gigs but teach him how to clean and dress himself. Sablon at one point anointed one of his band members, Andre Ekyan, one of the best French saxmen at that time, to be Django’s minder/driver using Sablon’s car. Django was dropped off where he was staying after the gig and picked up the next day. This story told me how much these successful bandleaders and musicians appreciated and loved Reinhardt’s powerful and expanding skills as a player. There is no way any member of an orchestra was ever granted this kind of treatment. Before rock and roll (a critical distinction) anyone who showed up unwashed in threadbare Gypsy clothing or didn’t show at all and not named Jim Morrison would have gotten the hook. The recordings that survive the period, though the arrangements were forgettable, display a 23-year-old Django playing improvised solos with complex arpeggios and scale patterns with increasingly astonishing power. But he was playing waltzes at tea dances. He needed more.

In the summer of 1934 Django was playing the Hotel Claridge in Paris for Louis Vola. Vola played accordion and led an orchestra with 2 pianos, another guitarist, a horn section of four, drums, bass and two violinists. This was a dignified gig, men in tuxes waltzing with women in jewels, nothing in the way of jazz. But one of the violins was a young man 2 years older than Django. His name was Stephane Grappelli. This meeting and a chance encounter when Stephane broke a string in the middle of a performance would propel these two around the world.

A taste. Recorded in 1937, penned by Reinhardt and Grappelli, “Minor Swing”.

Next: Django, Act 3.

Objective/Subjective: Here We Go Again

“Seeing as ‘objective review’ is an oxymoron, ‘subjective review’ is moronic.”

My contentious friend Michael Lavorgna—late of Stereophile and AudioStream, currently of his own site, Twittering Machines— recently posted that statement on Facebook. Michael often mocks unthinking convention, challenges authority, and incites debate. As the saying goes, you can take the boy out of Joisey, but you can’t take the Joisey out of the boy.

Wait: he still lives in New Jersey. Never mind.

Anyway, I think Michael has a point here. Maybe several of them.

Can a review be objective? If all you have is a collection of data, is that really a review—or just a bunch of numbers? And isn’t deciding what data to gather a subjective act? Likewise, interpreting that data?

I’ll fall back on the laziest trick in the writer’s bag o’ tricks: how does the dictionary define “review”?

First, we’ll have to find an online dictionary that isn’t just a holding page for an available site-name. The online presence of the Oxford English Dictionary gives us this definition: “A critical appraisal of a book, play, film, etc. published in a newspaper or magazine.”

One step removed: can there be a “critical appraisal” without subjectivity? I don’t think so: that’d be like sitting through the credits of a movie without having any knowledge of any of the names rolling past.

From a fast and dirty review (verb form, “examine or assess something formally with the possibility or intention of instituting change if necessary”) of “review” I’d say that Michael is correct.

I’ve been immersed in the world of audiophilia for most of my life, and am still puzzled by the contentious and extremist nature of the camps of objectivists and subjectivists. I see them as complementary parts of the whole: while certain preferences of listeners seem arbitrarily subjective, the more we learn about psychoacoustics, the more we see a rational, objective underpinning to those preferences.

Whenever the question, “nature or nurture?” pops up, my answer is always “yes”. I think it’s impossible to separate the two, and we are all affected by both genetics and environment.

And just as different folk perceive shades of color differently, it’s clear that we hear differently, as well. Just look at forum threads discussing recent audio shows: you’ll hear the same room, the same system, described as “detailed but not overly-analytical” and “lacking in snap and impact”; another room described as having “tremendous bass impact” and “monotonic bloated, boomy bass”.

Is one right, and the other one wrong? Possibly. Different demo material may present a system in radically different ways. Normally, one expects a show exhibitor to present their gear in the best possible light, but things happen. Especially when a showgoer demands to hear Crash Test Dummies. Or whomever.

I think it would be interesting to take a panel of 10 people or so, have them listen to several demo rooms, hear all the same tracks, and write their impressions of each system and each track.

I have a feeling the results would differ so much you wouldn’t believe folks were hearing the same things.

And you know—really, they’re not.

gives us this definition: "A critical appraisal of a book, play, film, etc. published in a newspaper or magazine." One step removed: can there be a "critical appraisal" without subjectivity? I don't think so: that'd be like sitting through the credits of a movie without having any knowledge of any of the names rolling past. From a fast and dirty review (verb form, "examine or assess something formally with the possibility or intention of instituting change if necessary") of "review" I'd say that Michael is correct. I've been immersed in the world of audiophilia for most of my life, and am still puzzled by the contentious and extremist nature of the camps of objectivists and subjectivists. I see them as complementary parts of the whole: while certain preferences of listeners seem arbitrarily subjective, the more we learn about psychoacoustics, the more we see a rational, objective underpinning to those preferences. Whenever the question, "nature or nurture?" pops up, my answer is always "yes". I think it's impossible to separate the two, and we are all affected by both genetics and environment. And just as different folk perceive shades of color differently, it's clear that we hear differently, as well. Just look at forum threads discussing recent audio shows: you'll hear the same room, the same system, described as "detailed but not overly-analytical" and "lacking in snap and impact"; another room described as having "tremendous bass impact" and "monotonic bloated, boomy bass". Is one right, and the other one wrong? Possibly. Different demo material may present a system in radically different ways. Normally, one expects a show exhibitor to present their gear in the best possible light, but things happen. Especially when a showgoer demands to hear Crash Test Dummies. Or whomever. I think it would be interesting to take a panel of 10 people or so, have them listen to several demo rooms, hear all the same tracks, and write their impressions of each system and each track. I have a feeling the results would differ so much you wouldn't believe folks were hearing the same things. And you know---really, they're not.

Dianne Reeves: Eight Great Tracks

When Dianne Reeves went with her Denver high school big band to the National Jazz Educators’ Convention in 1974, she probably didn’t expect her career to suddenly take flight. But among those who heard the teen sing there was trumpeter Clark Terry. He knew he was witnessing a major talent, and he helped her get a foothold in the most practical way, by inviting her to perform with him on some gigs. At one of them, the wide-eyed girl got to open for her hero, Sarah Vaughan, who was reportedly not just impressed, but threatened!

In 1976, at the age of 20, Reeves moved to L.A. There she studied voice with pianist/arranger Phil Moore, whose resume as a Hollywood vocal coach included work with Dorothy Dandridge and Marilyn Monroe. Reeves also sang with everyone who’d let her. She learned about Latin and funk by hanging with keyboardist Eddie del Barrio (leader of the band Caldera), about Brazilian music on a tour with Sergio Mendes, and about African and Caribbean rhythms during several years of performing with Harry Belafonte.

Within a decade, Reeves had established her place in the upper echelon of female jazz singers, and in 1987 was offered a coveted contract with Blue Note Records. Before that, she’d made a few albums on the Palo Alto Jazz label, highlights of which were subsequently re-released on Blue Note as The Palo Alto Sessions, 1981-1985.

Reeves is still an active performer, playing jazz festivals around the world. If you get a chance to hear her live, grab it. Until then, enjoy these eight great tracks by Dianne Reeves.

- “Sky Islands”

Dianne Reeves

Blue Note

1987

The opening track on Reeves’ Blue Note debut immediately establishes her as a jazz artist with classic chops but contemporary sensibilities and a knowledge of world music. Freddie Washington’s funky bass underlies an Afro-Brazilian beat spun out by Paulinho Da Costa on percussion.

Things to notice about Reeves’ voice, which are true whether she’s singing synth fusion like this or the standards she loves: 1) she never over-sings; 2) she has a massive range, which she can jump around as if it’s all equally accessible to her; and 3) her intonation is perfect.

- “Fumilayo”

Never Too Far

EMI

1989

“Fumilayo” is an African-tinged Latin jazz track composed by Reeves along with multi-instrumentalist George Duke. Reeves wrote the words, a call for hope and peace (“fumilayo” is slang for a friendly, joyous person). Luis Conte provides percussion this time.

The interesting thing here is the focus on the lower middle of Reeves’ range. That’s where her greatest power and most interesting textures lie. Hers is a vocal type associated more with swing/bop than Latin. It makes for a fascinating combination.

- “Sing My Heart”

Quiet after the Storm

Blue Note

1994

Because of her control over her voice, Reeves’ excels at contemplative pieces like this one. “Sing My Heart” is actually a 1939 Harold Arlen number, but David Torkanowski’s piano arrangement pushes it forward fifty years. The bowed bass-playing by Chris Severin contributes to keeping this version in the jazz realm, when it’s right at the precipice of pop.

But mostly, Reeves’ delivery is what makes this a great track. It’s an emotional conundrum: Off-hand in a way, but she’s concentrating deeply. Low-key in a way, but her anguish is on her sleeve.

- “Tenderly”

The Grand Encounter

Blue Note

1996

Despite her re-imagining of classics and love of contemporary jazz, Reeves is arguably at her finest when she’s singing jazz standards in a retro style. The first voice you’ll hear on this performance of “Tenderly” is that of Joe Williams; at age 77, he was an authentic link back to swing’s Golden Age. Harry “Sweets” Edison’s trumpet and Phil Woods’ alto sax make this an exquisite trio of soloists. Do listen all the way to that deliciously dissonant final chord, both singers at the very top of their ranges yet still subdued.

- “Dark Truths”

That Day

Blue Note

1997

“Dark Truths” is a 1988 song by indie pop singer Joan Armatrading. The contemplative sadness of the lyrics is ideal for Reeves’ penchant for quiet emoting.

Reeves puts a premium on clarity, singing the melody as simply as possible and with heartbreaking patience. Rather than improvise or decorate the vocal line, she lets pianist Mulgrew Miller add the jazz flourishes. This track is also one of many examples of Reeves hiring female artists –and particularly women of color — to work with. The drums are played here by Terri Lyne Carrington.

- “Fascinating Rhythm”

The Calling: Celebrating Sarah Vaughan

Blue Note

2001

Talk about a double helping of classic: Here’s a Gershwin song performed in tribute to Sarah Vaughan. This Grammy-winning album uses a full orchestra, conducted by Billy Childs, who also wrote the arrangements. Childs and Reeves go way back to the days when she first moved to L.A.

The arrangement takes a true be-bop approach to the well-known standard, never letting us hear it straight up – “Fascinating rhythm” is embedded in our ear like a Platonic form before the performance even starts, so why do it the way we expect?

It’s always a treat to hear Reeves scat. Like this record’s honoree, Reeves is always in precise control of her pitch and rhythmic articulation, two requirements for scat-mastery.

- “There’ll Be Another Spring”

Good Night and Good Luck

Concord

2005

The movie Good Night and Good Luck, written and directed by George Clooney, is about American TV news journalist Edward R. Murrow. There’s a lot to recommend this film, including the gorgeous and witty soundtrack by Dianne Reeves (who also appears in the movie as a singer). This album brought Reeves her second Grammy in a row.

Composed by Hubie Wheeler and Peggy Lee, “There’ll Be Another Spring” was recorded by Lee and pianist George Shearing in 1959. Quibblers might call foul, since that’s a few years too late for the movie’s story. But not only does it evoke the Fifties musically, it also has lyrics about hope during a time of sorrow and hardship – in this case, the McCarthy Era. The languid sax playing is by Matt Catingub.

- “Stormy Weather”

Beautiful Life

Concord

2014

For the last track, let’s circle back around to Harold Arlen, a composer Reeves has recorded many times. This is on her last studio album to date.

“Stormy Weather” has quite a history of stellar treatments by great female jazz singers. Reeves and Dutch musician Tineke Postma on soprano sax turn it into a mournful and moving duet. The famous melody reappears in fragments throughout Reeves’ harmonic meandering, as if she’s looking for the answer to why love has to hurt so much.

Billy Joel

He hasn’t made a rock album since 1993, but he sells out Madison Square Garden every month. As of this writing, 70-year-old Billy Joel has performed at MSG for 64 consecutive months, concerts that have grossed him over $130 million. He’s currently the third-highest selling solo artist in the U.S. Obviously, many fans still think of him as the quintessential American songwriter.

This native New Yorker started his solo career at 22, convincing producer Artie Ripp to put out his first record for Ripp’s indie label, Family Productions. As productions go, Cold Spring Harbor (1971) was an infamous disaster. Ripp recorded it at the wrong speed, so all the tracks are a quarter-tone sharp; he also failed to promote it effectively. Not surprisingly, it was Joel and Ripp’s last collaboration.

The contents of Cold Spring Harbor are another matter. The songs are cleverly structured, with sweeping melody lines and interesting harmonies. While the arrangements by studio and soundtrack legend Jimmie Haskell add richness and depth, it’s Joel’s piano playing (plus occasional stints on organ and harpsichord) that forms the foundation of his sound. The lyrics are smart yet emotional, at the edge of prog-rock for the intensity of their meaning. You’ll hear all these elements at work in “The Falling of the Rain”:

Joel wanted out of his contract with Ripp, and he lucked into the legal backing of Columbia Records when they heard his song “Captain Jack.” It was becoming sort of a cult hit in Philadelphia, and Columbia A&R recognized an up-and-coming star. While the legal battle over Joel’s second album, Piano Man (1973), was grim (Joel ended up splitting royalties with Ripp for every subsequent album until 1986), it enjoyed very good sales and garnered a solid hit with its title-track single.

One of the less-played cuts is “Stop in Nevada,” an early example of a Joel song that seems like it’s telling a story but is essentially more of a character study. He’s made this a specialty subgenre throughout his career. What makes this one unusual is the fact that it focuses empathetically on a woman’s experience and disappointment.

While Streetlife Serenade (1974) sold acceptably, it got some bad reviews and had no hit singles, at least not in the traditional sense. Compared to your standard rock star, Joel’s career has been oddly shaped, allowing his hits to develop over time. “The Entertainer,” “Souvenir,” and “Last of the Big Time Spenders” are more familiar now than they were when the album’s sales were at their height.

The cut “Streetlife Serenader” is a touching, thoughtful song whose power comes partly from the constant switch between major and minor modes. Joel’s piano playing is far more sensitive and sculpted than one usually finds among pop musicians, who instinctively bang the keyboard just to be heard.

Turnstiles (1976), the album that brought the world “New York State of Mind,” had a little gem on side 2, a tribute to an old friend called “James.” This loving and patient homage features intriguing harmonic twists, not to mention Joel getting comfortable with a simple synth sound. The critics who blasted this album for being “obnoxious,” distracted by the louder tracks, might have taken the time to listen more closely to “James.”

A new era of Joel’s recording career launched with The Stranger (1977), when he started a hugely successful 6-album collaboration with Phil Ramone as producer. It’s hardly controversial to say these six records are as strong artistically as they were commercially. Seven of The Stranger’s nine songs turned into smash singles, so we’ll proceed to the second Ramone-produced album, 52nd Street (1978), which has four non-single tracks for us to choose from.

Dave Grusin provided the spectacular horn arrangements for “Half a Mile Away,” a song that shows off Joel’s soul side. His usual drummer, Liberty DeVitto, contributes a bright and brittle backbone.

Next up was Glass Houses (1980). In the shadow of classics like “It’s Still Rock and Roll to Me” and “Don’t Ask Me Why,” it’s easy to forget one of the most beautiful melodies Joel ever wrote. “Through the Long Night” seems almost painful in its simplicity at first. But the more you listen, the more complexity you’ll find under its surface, from the mid-verse modulations to the word play: “All your past sins are since passed…”

Joel has expressed particular pride in 1982’s The Nylon Curtain, an album important to music history in part for being one of the first ever produced digitally. If you notice less saxophone than usual for a Joel album, it’s because his regular player, Richie Cannata, had left the band, so Joel just used a session musician for a couple of numbers. All the A-side tracks turned into powerhouse singles, including “Allentown” and “Goodnight Saigon.”

The B-side gets less attention, but only because of the album’s embarrassment of riches. “A Room of Our Own” is an old-school boogie featuring Joel’s sardonic wit and (critics have reasonably guessed) a tribute to the recently assassinated John Lennon in the rhythmic and vocal style:

After An Innocent Man (1983), another success, Ramone took the helm one last time. The 1986 album The Bridge offered three big singles, not to mention a duet with Ray Charles. Like most artists with long careers, Joel absorbed the industry’s changing sounds into his music; The Bridge shows him bowing to some New Wave conventions. For one thing, Cyndi Lauper shows up to sing backing vocals on “Code of Silence.”

The opening number, “Running on Ice,” is an obvious tribute to The Police, with a pulsing syncopated reggae rhythm. Joel even seems to change his voice to mimic Sting’s breathy tenor.

The following album, Storm Front (1989), had so many hits that we’ll just stop long enough to tip our hats and shake our heads. This record marked the end of Joel’s real commercial power as a studio artist. Little did he know that he’d barely tapped into his commercial power as a performer!