Loading...

Issue 74

Tom Fine: New Mercury Living Presence Analog Releases Part 2

[Tom Fine is a second-generation audio engineer, specializing in mastering and analog-to-digital transfers. The son of audiophile pioneers C. Robert and Wilma Cozart Fine, he grew up steeped in music and sound. His father owned Fine Sound and Fine Recording studios in New York City from the early 1950s to the early 1970s. His mother was director of Mercury Records’ classical division, and a corporate Vice President, in charge of the famed Mercury Living Presence recordings. These classic albums, most of them produced by his mother and recorded by his father, achieved state of the art high fidelity using 3 spaced omni-directional microphones feeding 3 tape tracks, which were then mixed to stereo directly in front of the LP cutting lathe (and, later, to a CD mastering chain). Since 2010, Tom Fine has been overseeing Mercury Living Presence remastering, working with state-of-the-art modern digital technology. He recently took a turn in the audiophile all-analog world.

The latest Mercury Living Presence reissues feature cellist Janos Starker: Bach’s Six Cello Suites and Dvorak’s Cello Concerto, to be released on 45RPM 200g vinyl by Chad Kassem’s Analogue Productions label. Tom Fine previously spoke with Copper about his parent’s work in issues #49, 50, and 51, and we are grateful for an opportunity to revisit with him about his latest works. Tom replied to questions posed by Copper’s John Seetoo, via email.]

[Part 1 of the interview appeared in Copper #73 — Ed.]

John Seetoo: Unlike in rock music, where a splice edit can be made on a drum beat and echo used to cover it, what tricks need to be used to mask an analog edit in classical music?

Tom Fine: This is an interesting topic. Mercury’s Music Director (and later head of the classical division), Harold Lawrence, was an amazing tape editor. He, and the artists, were very picky about what constituted a “perfect tape” and sometimes he employed note-by-note editing to get what everyone considered the best representation of the composition. You have to remember that all great classical music albums are productions. They’re not documents of a live performance. They are meant to be played many times over, so they need to be a somewhat idealized representation of the music, both in your sonic point of view (ie “the perfect seat in the perfect hall”) and in how the orchestra plays and interprets the music in accordance with the conductor. For difficult solo music like the Bach Suites, it’s just not possible to do complete perfect takes. So, Harold employed the full art and craft of tape editing. I would say his most interesting trick (and nerve-wracking, when the splice glue dries out or the splice otherwise fails) was adding a tiny sliver of tape in the middle of a splice to add just a micro-beat more space between notes. You have to keep the splice intact, in the correct order, keep it in the block while you clean the old glue off it, and then re-splice it perfectly straight so it plays without a hitch.

Here’s an interesting aside about splicing. The man who invented the tape splicing block, and many of the methods of tape editing used through the generations, was Joel Tall, originally a sound engineer and editor at CBS News. His splicing block was called the EdiTall, and his company was in Mount Vernon, NY, in lower Westchester County. He pioneered many tape editing tricks in putting together the famous Edward R. Murrow Columbia album I Can Hear It Now, in 1948. That album was one of the first hits on the new LP format. Tall left CBS in the early ‘50s to start his splicing-block company. Fast-forward to the present and I’m friends with Joel Tall’s nephew. There’s a nice online “museum” about Joel Tall and EdiTall, a lot of material donated by Tall’s daughter.

JS: How would you compare your past remastering of the Marcel Dupre box set referenced in your last Copper interview, with what you had to do on the two Starker albums? How does remastering a record with a polyphonic central instrument, such as the organ, differ from one with a primarily monophonic instrument like a cello?

TF: Well, first of all, listen to the Bach Suites. A cello can play a lot of tones at the same time. So, I wouldn’t call it a monophonic instrument like, for instance, an early Moog synthesizer. But you are correct in suggesting these are two different instruments and the recording acoustics were very different. The Bach Suites were recorded in my father’s studio in NYC, in what had been the ballroom of the old Great Northern Hotel on 57th Street (now the site of the Parker Meridian Hotel). In contrast, Marcel Dupre’s solo organ recordings were made in the massive Saint-Sulpice chapel in Paris and the slightly less massive St. Thomas Church in New York. A pipe organ wants the room air around it and uses the room acoustics and reflections to develop some of the sounds. For Starker, we chose to make this mix a bit more intimate, get the man right in front of you with the room around him. I felt that was the best way to hear all the technique and detail involved with Bach’s music.

For the Dvorak recording, I previously remastered orchestral recordings made in Watford Town Hall, outside London, so I was familiar with the room and orchestra sound. Because Mercury didn’t use extra “spotlight” or “filler” mics for concerto soloists, the balance to use is what the mics picked up. Starker was seated in the center near the conductor, slightly in front of the orchestra. My key balancing cues were placing the woodwinds and brass in proper balance and perspective vs. the strings, and then everything fell into place. In the case of the one Dupre recording with an orchestra, the for-the-ages rendering of Saint-Saen’s 3rd “Organ” Symphony with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and Paul Paray, that too was a case of balancing the orchestra and then the organ naturally fell into place. By the way, my remaster of that recording is on Qobuz high-resolution streaming. I just re-listened the other night and was again very pleased with how that turned out.

JS: Are there different approaches, equipment, and protocols when working in analog vs. digital for your kinds of projects?

TF: Yes and no, and this is a good question. The key, absolute bedrock fact, with good remastering in either medium is getting as good a tape playback as is possible. Basically, if you get the tape moving properly over the heads and have equipment that can turn that magnetized ribbon into the most accurate possible magnetic flux and then electrical signal, you’re off to the races. Then it’s a matter of knowing what you can do and what you might want to do to get to the end goal of an excellent sounding commercial product.

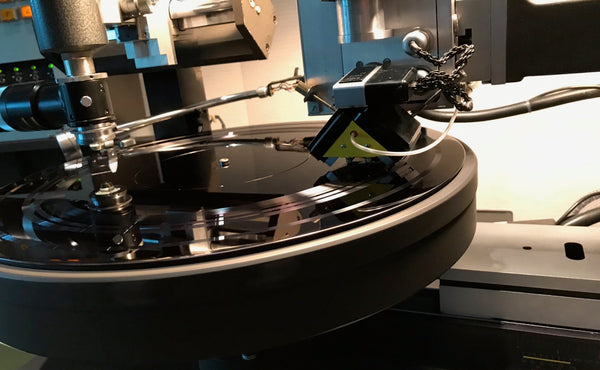

In the digital realm, we can use tools like Plangent Process to correct some of the inherent flaws of analog recording. You can also fix problems with a tape, such as a slight dropout or noisy splice. I think the audience for state-of-the-art digital reissues expects this, getting closer to what was actually in front of the microphones. When you work all-analog, you’re limited to the tools available in that realm. Plus, cutting lacquers and pressing vinyl are arts and crafts in and of themselves. So, as my mother did with the original LPs and also with her CD mastering, which was done in a much more primitive stage of digital technology, I chose to keep the LP mastering chain as simple and direct as possible and shoot for excellence at each stage: restore the tapes to excellent playing condition, get an excellent playback and 3-2 mix, and then rely on Ryan and Chad’s plant manager, Gary Salstrom, to know their arts and crafts and get a vinyl platter that sounds as much like what came out of the tape machine as is possible. When I played the test pressings, I was amazed at the results. Ryan made 192-24 digital recordings off the same mastering console as fed the lathe, and I think the LPs sound amazingly similar. He did a great job getting that lathe to etch into lacquer all the sound qualities and subtleties on the tapes that we heard and liked.

The big problem with LPs is there are so many ways to play them back. I can’t tell you how anyone’s turntable or cartridge is going to sound and they are more audibly variable than high-quality digital gear, in my experience. They’re as varied as speakers and headphones, so every person’s system is truly their castle. All I can say is, these LPs did achieve what Ryan and I were going for and they do sound like what came out of the tape machine and the mastering console. And Gary’s plant presses a damn quiet platter. Very impressive!

I do think the end goal for Mercury Living Presence has always, and will always, be the same no matter what the release medium or current state of the technology. The recordings were made to faithfully capture and transmit the sound of the orchestra and the intentions of the composer, conductor, and musicians. The point of the 3-spaced-omni recording technique is to let the orchestra balance itself, let the conductor control the dynamic range, and let the performers sit naturally in the overall acoustic of the room or hall. In making a release master, we’ve never messed with after the fact EQ or dynamics control, what you hear is what the mics captured. That aesthetic is important because I think it puts more control of the production in the hands of the musicians and conductor, and less in the hands of technicians like myself. This keeps the overall product more about the music and the performance than anything else. I can’t emphasize enough that “hearing into the score” aspect of Mercury recordings. For instance, with the Dvorak Cello Concerto, listen to how the flute interacts with the cello and listen to how melodies and themes move around the different sections of the orchestra, and back and forth with the cello. In all Mercury orchestral recordings, notice how the stereo image doesn’t fold down to “wide mono” when the full orchestra plays a loud passage, as happens when too many mics are used.

JS: Is Acoustic Sounds your “go to” label for vinyl releasing in the future for all analog projects you plan to remaster, and what other projects does Tom Fine plan to work on in the future?

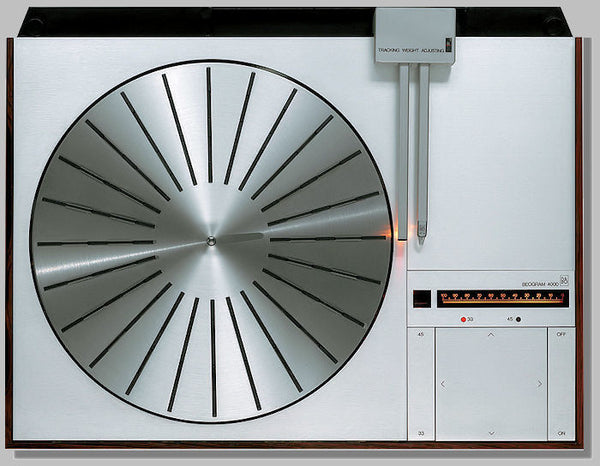

TF: Well, these first 2 albums need to sell well, so make sure to tell your friends about them! If they succeed in the marketplace, Chad and I hope to do more. We had very successful premiere listening sessions at the recent NY Audio Show. Robin Wyatt, of Robyatt Audio, was kind enough to set up a great-sounding vinyl playback system and host groups of about 30 people. We held three sessions, packed rooms each time. For the gear-heads reading this, here’s a good description of Robin’s setup and one of our listening sessions.

I also want to mention that, earlier this year, I remastered in the state-of-the-art digital realm all of the Mercury Living Presence recordings of violinist Henryk Szeryng, for this new Decca Classics box set.

Discs 30-36 are MLP albums. I worked again with Jamie Howarth and John Chester at Plangent Process. I think we got a really nice sound on all of these albums. Individual titles will be available in high resolution, I’m told.

Right now, in the studio, I’m finishing up a big oral history transfer project for a Western US state university. And I have to turn in my latest equipment reviews for TapeOp magazine and music reviews for Blackgrooves.org (Indiana University) by the end of the month. Then I’m looking forward to some down time through the holidays. Hopefully these new Mercury reissues sell well and there’s a market for more in the future. In a perfect world, I’d like to remaster the entire Mercury Living Presence catalog, bringing high-quality modern versions to today’s audience. I’d also love to do more mastering work outside of classical music. I love all kinds of music. Basically, I’ve been listening to recordings from the first day I figured out how to turn on a radio or put a needle into a groove. When it comes to sound and music, I’m a voracious omnivore.

Gibson to Close Memphis Factory

Regular readers of Copper, and especially of Industry News, have no doubt noticed that Ye Increasingly-Olde Editor has an obsessive streak big enough to be seen from space. I credit this to three things: growing up in a household of relentless newspaper folk, being a journalism student in the era right after Watergate, and the tendency innate to every Gemini: always forgive, but never forget.

I mention this as explanation for yet another Industry News piece on Gibson Brands. The company is significant to musicians and audiophiles alike: in addition to manufacturing iconic guitars, the holding company had significant shares in audio companies including Onkyo, Pioneer, TEAC, Esoteric, Cerwin-Vega, and Stanton amongst many others. The bewildering array of companies owned by Gibson can be seen in this chart that was part of the company’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing back in May.

Describing all the fallout of the Gibson bankruptcy would likely require a book, but one major outcome in the audio realm has been Onkyo’s loss of its reciprocal investment in Gibson, which precipitated the subsequent sale of its subsidiary unit, Pioneer Onkyo Europe (POE). Gibson still retains Cerwin-Vega, Stanton, and KRK monitors, but most of its other holdings in consumer audio companies are gone. Full details of Gibson’s reorganization can be found in the 230-page (!) joint reorganization plan submitted in October, and approved by the Federal Bankruptcy court in November.

At this point, what remains to be said about this whole tangled mess? Well, this: Gibson had previously said that the factory located on Beale Street in Memphis would be downsized and moved to a smaller (read: cheaper) facility in Memphis. It now appears that Memphis production of semi-hollowbody guitars will be shut down completely, moved to the main factory four hours east on I-40, in Nashville.

As one who lived in Memphis for 25 years, I can vouch for the longstanding, bitter rivalry between the two cities. Memphians mock the Bible-publishing and insurance heritage of Nashville, and Nashvillians view Memphis as a crude river town with scary music. I can’t imagine that Memphians will view Gibson’s departure as anything but the latest insult from the more-affluent city.

Val and Ed…and Amy

How would you react if you were suddenly face-to-face with one of your idols? I hope you’d be more prepared than I was on that day in 1984.

I remember the first time I laid eyes on Van Halen’s debut album in 1978. The front cover introduced Eddie and his Frankenstein Fender Strat, David “Diamond Dave” Lee Roth with his mic and hairy chest, and Alex Van Halen & Michael Anthony, practically blurred out. I found the album in a stack of promo records at my friend Bill Jr.’s house.

Bill Jr. was the child of a wealthy socialite family. He liked me because I was slightly older and knew all about hard rock bands – he was still into the Bay City Rollers. I was fond of Bill but loved his older sister Nicola who possessed even worse taste in music than her brother – all weepy singer-songwriters, so I could not figure out who owned that heavy Van Halen record. No one wanted it, and lovely Nicola let me take it home. As soon as I heard their version of the Kinks’ “You Really Got Me” and its intro “Eruption,” Eddie’s solo shredding masterpiece, I was hooked.

For the next six years, Van Halen provided my summer soundtracks. Back then, when other kids went to sleep-away camp, I participated in a bicycling program that took me all through New England, parts of Canada, as well as Northern California and Oregon. We rode all day, ate outdoors, and slept in campgrounds. On occasion, the group would have a layover at a facility that also accommodated RVs, and those places had luxuries like laundry machines, pay showers with hot water, a snack bar and rec hall complete with a jukebox! Electronic entertainment was rare on the road, so a bit of television, a movie, or some current music was a treat.

Depending on the region, there might be a lot more Molly Hatchet and Lynyrd Skynyrd on the jukebox than New York Dolls and Ramones, but Van Halen was universal. I played “Dance the Night Away” (Van Halen II, 1979) during my trip to Vermont, “And the Cradle Will Rock” (Women and Children First, 1980) in Quebec, “Unchained” (Fair Warning, 1981) in Oregon, and multiple cuts off Diver Down (1982) in New Hampshire. With so many kick-ass tracks including “Where Have all the Good Times Gone,” “Cathedral,” “Little Guitars,” “Dancing in the Street,” and “(Oh) Pretty Woman,” I consider Diver Down as Van Halen’s finest record.

In 1984, Van Halen released 1984, and it turned out to be their last album with Roth. “Jump” and “Hot for Teacher” were mainstream smash hits, as well as popular videos on the nascent MTV channel. We didn’t have MTV at my house, but I watched hours of it at my after-school job as a houseboy for a magazine publisher. In addition to walking dogs and running errands, I also worked his events which were attended by many famous people of the day. Manhattan society parties prided themselves on a variety of guests, so it was not unusual to see Andy Warhol, a porn star, and Dr. Ruth Westheimer all crowding around the sushi bar. It was no big deal. Bill Jr.’s parents had equally star-studded parties at their mansion and I followed his example by remaining calm, cool, and collected.

Due to circumstances beyond our control, my family moved from one of Manhattan’s ritziest zip codes to the edge of Hell’s Kitchen, from my own suite on the 12th floor overlooking Park Avenue to living directly above an all-night diner and sleeping on the living room floor. I stuck out in the rough neighborhood with my private school uniform as I dodged sleeping drunks, assorted tough-guys, panhandlers, and the johns who skulked to the bordello over on 10th Avenue at all hours.

My childhood dog, Amy.

One August day in 1984, I was walking our fancy Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, and a young couple appeared accompanied by a man in a suit walking slightly behind them. They had matching blow-out 80’s hairdos. The woman noticed my dog and squatted down, “Awww, what’s your dog’s name?” People always wanted to pet her, and it got a little annoying after a while – especially when they talked to the dog as if it were walking me, but this lady was so sweet, pretty, and familiar. “Amy,” I answered nonchalantly. Then, I looked up and saw the smile. “Hi,” he said through a puff of smoke. My brain was straining to place these faces. I had seen them a thousand times on TV, but I could not process their features fast enough. By the time I was done being flummoxed, it was over. I stood paralyzed as Eddie Van Halen and Valerie Bertinelli (aka Barbara Cooper, America’s sweetheart from One Day at a Time) walked away down 57th street ̶ likely towards one of the studios that were in that area. It was like starting the best dream of your life just to be robbed of it by the cruel alarm clock of reality.

“Was that really them?” I second-guessed myself, “It was! I can’t believe I was standing right next to Eddie Van Halen and Valerie and I didn’t say anything, not a single word except my dog’s name! I don’t think I even said “hi” back to Eddie. What an idiot!” For the first time in my life, I was overwhelmed by celebrity.

I always regretted not being more engaging and quicker on my feet, but I was 18 and in a bad state. There was a fasting craze going through my school, and all I ingested for a few days was black coffee and clove cigarettes. On top of that, my high school girlfriend broke up with me preemptively in preparation for SUNY New Paltz. And then there was our shitty new apartment in a dingy tenement building. I don’t know what I could have said to Eddie anyway. In my depressed mood, I might have begged him never to break up with my boy-crush Diamond Dave ̶ there were rumors of personality clashes and beefs over the use of keyboards. But they did break up soon after, and my childhood came crashing to an end: the original Van Halen disbanded, high school was over, my girlfriend was moving on, and I was getting too old for camp.

When Van Halen reunited with Roth for a tour a few years ago, I was there. I never got a chance to see them live, but despite the passage of thirty years, Eddie played seamlessly while smiling his way through the show. It’s amazing how distant summer days came flooding back on that humid night at Jones Beach amphitheater. As an older Dave Lee sang each song, I was suddenly transported to 1978 and hanging out with Bill Jr., since deceased, awaiting each new Van Halen record, cycling around America carefree, and running into Eddie and Valerie. I told my concert mate the story, savoring it in retrospect. “You saw Valerie BER-TIN-ELLI up close, did you freak out?!” Clearly, my friend Ken would have made a complete idiot of himself as he drooled all over lovely Valerie.

I always wonder how I would react if I had it to do over again. Anything I can think of is so trite. The memory now is almost better because so little happened. Instead of regretting an embarrassing statement, question or action, I can just appreciate how nice that Hollywood couple was to a random dog and star-struck teen on the streets of New York City. It was great to share one quick unforgettable moment with them.

François Couperin

The Year of Couperin is drawing to a close. What, you haven’t celebrated François Couperin’s 350th birthday yet? There’s still time, and I’ve even got a playlist of new recordings for your party.

Couperin was born in 1668 into a family of musicians as important in France as the Bachs were in Germany. Famed for his virtuosic organ and harpsichord playing, it surely surprised no one that he received prominent positions and commissions in French royal circles. But the most lasting contribution the monarchy made to Couperin’s career and the future of keyboard playing was a 20-year “royal privilege to publish.”

A big merci to Louis XIV for giving Couperin the chance to save for posterity his hundreds of works for harpsichord, organ, small ensemble, and voice. And Couperin’s textbook about how to play the harpsichord, focusing mainly on ornamentation, is a bible for early-music keyboard players.

So many new Couperin recordings and remasters came out in 2018 that I can only give a taste of the several genres Couperin wrote in. It makes sense to start with harpsichord music, which is the best represented in his published books and the most-often played these days. Les Muses Naissantes (Ricercar) is a recording by harpsichordist Brice Sailly and colleagues. Sailly plays a few of Couperin’s solo ordres, which were basically suites of dance-inspired movements similar to those Bach wrote for various instruments.

When you listen to Couperin’s harpsichord music, some good points of merit to focus on are clarity of ornamentation and an organic sense of phrasing. In other words, while the music should be delicately ornate, it should also breathe. It’s easy for a harpsichordist obsessed with getting in all those darn notes to end up with a heavy or robotic sound. Not so Sailly. Here is his masterful, understated rendition of the 20th Ordre:

Les Muses Naissantes also includes some ensemble works by Couperin played by the 7-person La chambre claire. Soprano Emmanuelle De Negri’s voice has a captivating lilt in this secular song with instrumental accompaniment, which would probably have been used to entertain people at court. Unfortunately, Couperin did not write many such songs, or at least few still exist.

For another approach to Couperin’s keyboard music, try the almost frantically virtuosic playing of Bertrand Cuiller on his new release (which promises to be a series), François Couperin L’Alchimiste: Un petit théâtre du monde – Complete Works for Keyboard, Vol. 1.

Because this recording is on Harmonia Mundi, only a teaser is available on YouTube, but it’s enough to give a sense of Cuiller’s startling and ferocious playing.

You can hear the entire album on Spotify:

The record’s title, The Alchemist: A little theater of the world, refers to the descriptive names that the composer often gave the individual movements of his ordres and the sense it gives us of how colorful life was around courtiers. For example, there’s the second movement of the 11th Ordre, which the composer titled “Sparkling, or Lady Bontems.” Cuiller is a technical wonder. It might be tempting to discount his playing as nothing but powerful flying fingers, but remember that Couperin himself was prized for his virtuosity. I bet King Louis would have loved this performance.

By no means is Cuiller’s playing all flash; he can strike a meditative mood when needed, for example in the Allemande first movement (nicknamed “L’exquise” – The Exquisite Woman – but for whom? Ooh la la!) of the 27th Ordre. Yet it doesn’t have quite the organic breathing motion of Sailly’s touch.

These days, historically informed performance (known as “HIP” in the business) is considered the standard for approaching this repertoire. It’s surprising, then, when you hear new recordings that don’t take authenticity into account. I wanted to acknowledge one from a few years ago, newly available on YouTube, by Iddo Bar-Shaï. He plays Couperin on a modern grand piano and with a late nineteenth-century sensibility, especially in terms of rhythm.

The album is called François Couperin – Les Ombres Errantes / Pièces pour Clavecin, and it’s on the Mirare label. I find the interpretation very tender and warm, but I have to constantly stop myself from judging it by the tenets of early-music practice.

One Couperin fan who was fully committed to the composer’s special year is Christophe Rousset, harpsichordist and leader of the ensemble Les Talens Lyrique. Throughout 2018 they have been performing 350th birthday concerts all over Europe, and they also released a new recording on Aparté of the 1726 set of ensemble works called Les Nations. This often-played collection includes four paired sonatas and suites: La française, L’espagnole, L’impériale, and La piémontaise. So, it’s not exactly about four nations, and all four sound more Italian than anything.

Rousset’s 10-member band plays with earnestness and energy (sometimes a bit too much of both). It’s fun to hear the blending of their Baroque bowed strings, plucked strings, flutes, and reeds – quite a different sound from the modern versions of these instruments. Here’s a live excerpt from L’espagnole.

And you can hear the whole album on Spotify:

Speaking of Les Nations, I would be remiss not to mention an important remastered recording that came out during this birthday year. Longtime leader of the early-music movement, Jordi Savall (viola da gamba), along with other big names like Monica Huggett (violin) and Ton Koopman, recorded Les Nations in 1983, and the album has just been re-released on Alia Vox Heritage.

You won’t find better baroque playing than this. Here’s their exquisite rendition of the Sarabande from Couperin’s First Ordre. They play with such patience and thought, and the ornamentation is so perfectly coordinated among the instruments, it’s like a single being is making multi-timbred music.

And just to prove again that older can be better, here’s a quick look at the impressive François Couperin Edition, a 16-CD set of remastered recordings on Erato/Warner Classics. Among the artists included are harpsichordist Laurence Boulay (whose Couperin has never before been on CD), Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, John Eliot Gardiner, and one of the most important conductors of Baroque vocal music, William Christie. Here is Christie’s group, Les Arts Florissants, featuring sopranos Patricia Petibon and Sophie Daneman performing a genre not often associated with Couperin – a sacred motet:

Monsieur Couperin, you were a man of many talents. Bon anniversaire!

Christmas and Us

When I was a kid, on Christmas Eve I heard my parents taking presents from an unused room next to the bedroom I shared with my younger brother. The full blown truth of Santa Claus came crashing down on me all at once and at the worst time, right before Christmas morning. I was so shocked I woke my brother, two years my junior, and broke the news to the poor little tyke.

Yes, we were tight my brother and I.

I have a dream at least once every season where I’m coming home from work on Christmas Eve and as I walk through the door I realize we haven’t picked up a tree or gotten any presents for the kids. We run out to the tree lot (closed) and to the stores for presents (also closed). The feeling is horrid, the dread of seeing the kids in the morning and no tree, no presents. I’m actually sick, looking at the expectant faces of the kids and my wife’s disappointment. Then I wake up. It’s the only good thing about bad dreams; when you wake and realize all is well it’s worth the trip.

The trappings of this glorious holiday are, and always have been, important to my family and help bring the warmth to our holiday. We had poor years when we were kids, and sometimes we got presents that were re-wrapped from last year. But somehow it didn’t matter; it’s not about the presents anyway.

Growing up we never put up the tree until Christmas Eve, a hold-over from the days when the parents put the tree up after the kids went to bed and the story was that Santa brought it. Christmas Eve afternoon after we’d spent four hours harassing Dad he’d go outside to get the tree. Naturally we always bought a tree too big for the cellar stairs and door and often he’d have to cut off so much from the top and bottom that we ended up with more of a Christmas shrub. The kids’ job was to get up in the weird attic and pull the decorations down while Dad puffed that tree up the stairs and into the living room, all the time broadening our language skills when he barked a foot on something we’d left for him.

We had a 6-foot wooden candy cane that Dad made in his shop that would go over the front door the weekend before Christmas. Pop would train two floodlights on it, one green and one blue. There were houses in our neighborhood that had more lights and decorations, but somehow the sight of your own house and that big stupid candy cane was warm and wonderful. Still a great memory.

Also the weekend before Christmas we’d spray that messy white stuff from a can over stencils in the windows. That shit started falling off the window immediately and you had to listen to Mom with her ‘never again’ mutterings. The decoration boxes had all the tree stuff but also all those knickknacks that went back to that mystical land where Mom and Dad were children somehow.

We have a house-full today. It takes a full day to pull the crap out of the attic for the outside decorations and to put those up. My son Dean insists on doing this (thank you Lord) because he has his own way. His friend Nathan has been helping him since high school. Nathan lives in Omaha now but he still showed up this year.

Another day is spent on the inside. There are all those damn boxes in the basement in a closet under the stairs. Crap we’ve been gathering for 44 years of marriage. All the normal day-to-day stuff has to come down, the house cleaned and dusted, then out come 4987 Santa and manger figurines, angels, fake silver reindeer, candlesticks and festive candles. There are Christmas bears, various sleighs with reindeer flying to the ceiling. From the poor years when we couldn’t afford to buy decorations there are handmade bulbs, macaroni wise men, candy cane sleds and this tree Diane and I made at one of our first Christmases back in 1978. Still standing, if barely. There’s an Elvis Christmas tree that goes in our bedroom on a hope chest complete with a small village of Grace Mansion, the front gates, and a pink Cadillac with a tree in the back. After 12 hours the junk is all out.

I put the tree up. That includes assembly (we gave up on a live tree years ago), light testing on 15 or 16 strands of bubble lights, old C5’s, blinking candles and stars. Next is the garland, then at last the bulbs. We have two boxes of bulbs, possibly 75 in each box, so many they can’t all go up on the tree. The kids like to help with this part; the sentimentality of these ornaments is a special moment every year. There’s a bulb for each year since 1980, when we moved to Colorado. There’s a Baby’s First Christmas bulb for every child and even one dog. There are bulbs from all the family vacations in New York, Steamboat Springs, Santa Fe, Estes Park, Las Vegas, and campgrounds all over Colorado, Wyoming, and South Dakota. M&M and Coke bottle ornaments from Las Vegas. Santa riding a Harley and sports ornaments for all the teams we collect for. Two from The Christmas Story that have recorded lines from the movie. Several more Elvis’s. Old wooden eggs, ancient bells, and clear icicles.

By the time we get done the damn thing looks like a still shot of an explosion a split second after detonation.

There are globes on the mantels crammed with green, silver, and red paraphernalia. One is a globe we’ve had since the kids were little, depicting a Santa peeking in on a sleeping child. 16 years ago, it sprang a leak and I had to empty it, fill it back up with distilled water then seal it with that red gasket goop you use on engines. But before I sealed it I couldn’t resist signing the back wall.

One year, my daughter Bree made a Santa sleigh and reindeer for Dean out of pipe cleaners. It’s getting hard to move; it wants to fall apart, but it goes on the downstairs mantle every year. Santa appears to have expired 15 years ago with a bad embalming job. A little creepy, but it would have to burst into flame to not get on that mantle.

This year a little panic ensued when we were down to the last box and we hadn’t found my plastic squeaky Santa yet. This little guy sits next to my chair every season. He came from my childhood and I remember him standing on our mantel every year growing up. And as it turns out, every year. When I moved out Mom gave it to me and told me he was bought and placed in my crib on my first Christmas.

I’m 64 years old. Think what a miracle it is we still have him. Now my kids remember him from every year.

Downstairs in the family room we have the village that gets set up on Gramma’s old hope chest. Dean insists on doing this as well, and you’ll lose a hand if you move one item. I move something every year just to piss him off. And yes, he knows where each piece goes.

So why am I boring you with all this drivel about our traditions? I know you all have traditions and decorations in varying degrees. Some of you go as fruitcake as we do, some have just a few decorations, and some do none. Each unto his own. But I recently had someone come into our home and exclaim how lucky we were to have so much stuff. Well we are lucky, that is true. But we didn’t just go out and buy everything; it’s accumulated over 44 years and some even longer. The first village piece started with our first Christmas together, it’s over in the upper right. We add a piece every now and then, and somehow you end up with this hodgepodge. Same with the knickknacks and bulbs. We had plenty of lean years but we just hung onto stuff.

We do enjoy Christmas and appreciate our reminders. The reminders include the Christmases when we had no tree and no presents. One year we couldn’t afford a tree. When a sweet but criminal friend of ours found this out, he raided some rich guy’s yard and cut us a tree. We shouldn’t have kept it but the looks on the kids’ faces…In a few recent years Diane and I didn’t get each other gifts, we sent gifts to the kids but that was all the money we had. It happens. Times are rough sometimes and often for years. Keeping good memories is critical to getting through those times.

The Christmas season brings us the special memories, even the lean ones. Stress is also part of the season but we have to remember the small things that make us happy. The celebration of the birth of the Messiah has ended up being a crazy spell with the shopping, visits, family, food, and generally bad movies. But in between the mall visits and last-minute rushes is the house on the corner where the only decoration is a green porch light bulb. Love that.

Merry Christmas All.

Killing In The Name

At this point, you might be forgiven for thinking that I am picking bands for my piece JUST to piss off our Editor. Nothing could be further from the truth, it just appears to happen EVERY time.[Oh, please—it was just that damned a-ha—Ed.]I am more focused on bringing to light the brilliant work that goes into songs that, at first blush, may not seem to deserve this sort of analysis. I feel that Rage Against the Machine definitely fits into that category. They should not be over-looked OR under-appreciated. What Brad, Tim, Tom, and Zack, managed to pull off is nothing if not revolutionary. And the level of musicianship is extraordinary.

The Players:

Drums – Brad Wilk

Bass – Tim Commerford

Guitar – Tom Morello

Vocals – Zack De La Rocha

The Story

Zack De La Rocha and Tim Commerford have been friends since attending elementary school together in Southern California. In junior high, they both played in the embarrasingly-named band, Juvenile Expression. It didn’t last long; Zack went on to be the front-man in the straight-edge band Hardstance, and then played in the hardcore band Inside Out, before discovering, and falling in love with, hip-hop. At, roughly, the same time, Tom Morello was playing in some bands and hanging out with different characters in the scene. One of these was a lad who went by the name Maynard James Keenan, he would go on to form a band called Tool. He was ALSO the bloke who showed Morello what Drop D tuning did to the sound of a guitar.

Morello was converted! I love little moments like that. Where two characters who go on to cast LONG shadows over music meet in their nascent days, and that meeting has a profound effect on both themselves AND each other. Maynard was ALMOST the lead-singer of RATM. Imagine, if you will, what THAT would’ve sounded like, but I am getting ahead of myself.

Morello’s band Lock Up went the way of the dodo, but its drummer, Jon Knox, encouraged him to meet and jam with Zack and Tim, even though he wasn’t interested in drumming for them himself. Morello reached out to a kid named Brad Wilk, who had auditioned for Lock Up but hadn’t got the gig. He did. They jammed. It worked. Band created. A guy named Kent McClard had known of Inside Out and been friends with them. At one point in his fanzine, No Answers, he had coined the term “rage against the machine” and a MILLION t-shirts would be emblazoned with it within a couple of years! Tom and Co. had their band, had their name, and with it, their manifesto. They made a demo tape; 10 of those songs made it onto their debut album. Which has 10 songs on it. You do the math. That’s it. Fucking amazing. They played their first gig on Oct 23rd, 1991, and their eponymous debut album was released in November of ’92. Brilliant. Every label wanted to sign them, but they went with Epic because, as Tom put it, “Epic agreed to everything we asked—and they’ve followed through…We never saw a[n] [ideological] conflict as long as we maintained creative control.” This was how they made peace with becoming part of the “machine” that they were “raging” against. They seemed destined from Day 1.

Killing In The Name

The song has eight lines of lyrics. And 17 different iterations of the word fuck. It also features one of the sickest riffs to come out of the 90’s. Don’t forget that at this time Grunge had a strangle-hold on the musical minds of MTV Culture. This shit wasn’t THAT! I have a particular fondness for this record, as it was brought into my life when I was in college, working at my college radio station, WPUR, SUNY Purchase, Purchase, NY. Our Hip-Hop Music Director was my friend Ron Archer, who would go on to die in his early twenties of a brain aneurysm. A horrible, tragic loss, of a wonderful bloke. RIP Ron, you are missed still. He was ALSO Epic’s East Coast College Rep. One day he hit me up and said “You gotta come to my room…I’ve got some new shit that’s gonna BLOW YOUR MIND!”

Ron was not one for hyperbole, so, as soon as lunch was completed, I hightailed it to his dorm room where, upon entry, he handed me a CD with the famous Malcolm Browne photo of the self-immolation of Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức on the cover, and the name “rage against the machine” in broken type-writer font below it. “What the f’ is THIS?!” I remember asking, just as bombast of “Bombtrack” ripped out of the speakers. I WAS blown away. And Ron’s shit-eating grin let me know that I was right. We sat in silence as “Killing In The Name” began and I was converted. I won’t ever forget sitting and listening to the whole album that day. The second person on our campus to know what was coming. And one of the few to hear it in the nation. A BRILLIANT memory that I owe Ron for. Thanks man.

When Tom first moved to LA, he had a couple of jobs to help pay the rent. One was to strip under the name Tom “Meat-Swinger” Morello, true story, and the other was teaching kids the wonders of the Ol’ Six String. It was during one of those lessons, ironically enough focusing on the glory of Drop D Tuning, that he bumped into the riff that would become “K.I.T.N.” He stopped the lesson, recorded the riff, and then played it to the lads at rehearsal the next day. Between all of them, they beat the riff into a song that would go on to drive their debut album to 3 million records sold. Quite an accomplishment for a song that sounds RIDICULOUS on the radio with all of the “fuck’s” taken out.

TO THE TAPE!!

The song starts with some BIG OL’ CHORDS! And then, almost as quickly, it stops, and Brad SOMEHOW gets away with using one of the least metal instruments of all time, the cowbell, which is, ironically enough, made of metal, to create a signature moment in 90’s music. You could play just THAT bit to almost anyone who was in their teens/early twenties in the early 90’s and they’ll know EXACTLY what song it is. Quite an accomplishment. And then we’re OFF! This track is the definition of bruising. Such a sick back-beat. Rap/Metal, unfortunately, owes most of its DNA to this record. There are some great conceits in the mix. Andy Wallace’s contribution to the flawless nature of RATM‘s debut cannot be under-stated. There are few mixers who can give you the delicacy of Maroon 5 and the bombast of Slayer all in the same resume. He is one of my favorites at the board. There are some inspired choices made. He blooms the snare with a little gated verb in places, and then dries it up in others, changed the size of the kit’s sonic depending on the need. For instance, in the “Now you do what they told ya!” section there are NO room mics used, so the kit becomes tight and claustrophobic, only to be allowed to explode back out again as the chorus begins. At the 4:10 mark, our boy Brad starts to REALLY earn his keep with some gorgeous fills, flourishes, drama, and cacophony, before the final Rock ‘n’ Roll ending brings us to a climactic close. Balls out! A beast of a track. #swagger

Tim Commerford is one of music’s best kept secrets. Perhaps, in any other band he would’ve been greater appreciated, but when you’re in a band with Tom Morello, you might tend to get a little over-shadowed. It’s unfortunate because Tim’s instincts are spot-on, ESPECIALLY in this track. This is the DNA of RATM on full display. He mirrors Tom’s riff, adding the occasional flourish, and counter-melody, as well as judicious usage of some gnarly FUUUUUZZ, just the ONCE, in complete support of the theme of the song melodically, and also paired beautifully with Brad’s 12-cylinder explosions. Check his playing in that last minute of the jam! RIDICULOUS! He also has some of the most incredible tattoos to ever grace a musician. Entirely individual to him, as one would expect. Exactly like his bass playing. Tim is the Real Deal. Google “Rage Against the Machine Bassist MTV video Music Awards” for the final convincing. #renegadeoffunk

Tom. What can you say? Nothing. Just watch THIS.

There it is. It’s shocking that it took until the early 90’s for someone to significantly change the way that the guitar sounded, and its usage in music. The person who had pulled it off prior, in the 80’s, was The Edge. That was the last time someone played something and you said “Wait! Wtf is THAT sound?!” Morello re-invented the guitar. That’s one HELLUVA thing to get done in your early twenties. He just took his guitar, had the pick-up switch re-wired to emulate the Transformer switch of a DJ mixer, put it all through a Dunlop Crybaby pedal, followed by the Digitech WH-1 Whammy Pedal, straight into the amp, and BOOOOOOM! A revolution in sound. Drop that D and be done!

I once spent 3 hours in an LA parking lot waiting for AAA to show-up to let him into his 70’s Duster and just talking shit with Tom. I’ll tell you this…he’s one of the best people I’ve met in the industry. I’d go to war for Tom Morello. Enough said. Listen to audio of the radio segment and watch that video. There’s a reason he’s “Tom Morello.” Oh, and my FAVORITE work from him is his lead in Audioslave‘s (one of the worst band names EVER, btw) song “Like A Stone.” Video below. Check it. Cornell’s performance is also legendary on that thing. And Tom is a TOTAL NERD!! Uncool has never been cooler. #armthehomeless

Zack de la Rocha was destined to become Zack de la Rocha, of this there is NO doubt. His paternal grandfather, Isaac de la Rocha Beltrán (1910–1985), fought in the Mexican Revolution as a revolutionary and was an agricultural laborer in the U.S. Pair this with Morello’s degree in Social Studies and Poly Sci from Harvard, and you’ve got two kids with VERY big brains, and even bigger mouths, joining forces to make a POINT! There are eight lines of lyrics in this song. That’s it. Eight. And he imbues each one, each repetition, with the force of a call to arms that cannot be resisted. It is a brilliant move. All you have to do is to see them live to see how effective it is. The crowd sings EVERY word. Screams it. Yells it. Feels it. There are 17 fucks at the end. Each one heavier than the one before it. His voice is a megaphone of emotions. Unbelievable to think that they INVENT this. They are definitely wading through waters that Faith No More traversed prior, but this ISN’T that. This is Revolution!

If you never got to see them live, you missed out. Four dudes making the noise of 10. Enormous. But, the oft-overlooked thing when it comes to Zack’s vocals is that he MEANT it. This performance is anything BUT a performance. And you can feel that. This is real for him. Real for all of them. They know that they signed with a major label, they know that the duplicity is obvious, you COULD call them on it, or, rather, you could try. But, not once you heard them. Nope. There is a skill to being able to create a melody out of spoken word poetry and de la Rocha is a skilled MC. It shouldn’t be discounted, also, that he continued to do this for four albums and not ONCE did he repeat himself, or did the joke get old. Each song is a thing unto itself and each an opportunity to say something of meaning. Something to shake up the audience. One can see how being in a band with a guy that means it THIS much could become exhausting…and, by all accounts, it was. But, it ain’t easy being that dialed in. There’s a LOT to rage against. Period. #wegottatakethepowerback

Rage Against the Machine called it quits about 7 years ago. They’ve all gone on to other projects and other callings, which is unfortunate. If ever there was a time to hear what George Carlin, Brad, Tom, Tim, and Zack, would have to say…it’s America, and The World, in 2018.

Go back, grab Rage Against the Machine, put it in the car, turn it up, to the point where you are endangering the lives of your speakers, put the windows down, and drive around your ‘hood yelling “Fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me!” at the top of your lungs. You’ll feel a LOT better.

I promise.

Until the next one,

cjh

PS – You can find me on IG, Facebook, and here if you want any info about The Sessions and where to catch me live.

Their first public performance:

Their insane performance at Woodstock ’99:

The Police

For some reason, The Police are best known today for two particularly creepy songs: “Don’t Stand So Close to Me,” in which ex-teacher Sting references Nabokov’s Lolita while describing a female student’s crush; and “Every Breath You Take,” a favorite song at weddings even though Sting has made clear that it’s about a stalker. I’d say it’s past time for a look back at some other Police tracks!

By coming up with an original blend of rock, fusion jazz, reggae, and punk, the three members of The Police – bassist/singer Sting, drummer Stewart Copeland, and guitarist Andy Summers – helped usher in the British New Wave. They were exactly what a lot of young people were looking for: intelligent, stylish, musically skilled rebels. Hats off to A&M Records for realizing that esoteric can sometimes sell if it comes along at the right time. While the Police made only five studio recordings, all are important works of popular music, and all are on A&M.

With Outlandos d’Amour (1978) the band showed its unique voice, mesmerizing new fans with its plaintive single “Roxanne.” It’s one of the most artistically worthwhile (not to mention best-selling) debut albums ever. In large part, this is thanks to Sting’s emotional but thoughtful songwriting.

Copeland had not yet found his compositional legs, but he is given co-author credit on “Peanuts.” The frantic pace and angry mood of “Peanuts” is a good reminder of The Police’s connection to the burgeoning British punk scene in their early days. Not surprisingly, the drums take center stage in this number about being disappointed in a former hero. The lyrics sung by Sting here are also by him; Copeland had originally composed this song with different words.

It’s also interesting to hear Summers’ hysterical, dissonant scrabbling on the guitar, a style not found in any of the band’s singles. For all their originality and weirdness, The Police don’t usually sound out of control.

The singles “Message in a Bottle” and “Walking on the Moon,” off 1979’s Reggatta de Blanc, proved that Sting’s quirky worldview could consistently appeal to millions. Both of those singles hit number one in Britain and were smashes in the U.S. as well. The Police also won their first Grammy for this record.

Unlike the first album, the tracks on Reggatta are a nearly even mix of Sting and Copeland compositions. “Bed’s Too Big Without You” is Sting’s; it luxuriates in his love of reggae more thoroughly than most of the band’s catalogue. They went all-out in getting that Jamaican vibe, including the reverb associated with bands like Bob Marley and the Wailers and Steel Pulse. Rhythmically, the empty downbeat and double-emphasized second beat of each bar is a classic reggae trope.

We get to hear another side of Summers’ guitar playing on “Bring on the Night.” One of his favorite composers is Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959), important for his intertwining of Western European counterpoint and the guitar traditions of Spain and his native Brazil. The gorgeous fingerpicking patterns Summers plays against Sting’s voice in the verses are meant as a tribute to Villa-Lobos.

Two Grammy Awards awaited the 1980 album Zenyatta Mondatta: Best Duo or Group Rock Vocal Performance (“Don’t Stand So Close to Me”) and Best Rock Performance (“Behind My Camel”). The latter is an Andy Summers composition and one of two instrumental tracks on the album. Although the song is in eight-bar phrases in 4/4 time, the most common configuration in rock music, the bass and drum syncopation lies in an off-kilter relationship with the guitar, making the meter seem complex and uneven. There aren’t many pop tracks with only two chords and just a single eight-bar idea repeated for over three minutes; the result is an authentic impression of trudging along an endless desert.

Zenyatta Mondatta also finds The Police showing their socially conscious side. Sting’s lyrics for “Driven to Tears” confront those who witness suffering in the world and do nothing about it: “How can you say that you’re not responsible? What does it have to do with me?” This might come off as condescending if Sting didn’t seem to be including himself in the guilt: “My comfortable existence / reduced to a shallow, meaningless party.” The rhythmic fluidity of those lines creates a sense of lamentation, like someone so distressed that he blurts out his pain in waves of rambling words.

In their first foray without co-producer Nigel Gray, Ghost in the Machine (1981) paired The Police with Hugh Padgham, who would go on to produce hits with Phil Collins, Human League, and others. The over-bright, synthy production does not do the listener any favors, unfortunately. The singles from this album are an especially energetic group, including “Spirits in the Material World” and “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic,” seemingly intent on emphasizing the pop angle.

While the album’s songs are mostly credited to Sting, there’s less use of reggae rhythms and harmonies than on the earlier records. And it seems like there’s more focus on Sting the rock star than on The Police. One of the non-single tracks features him pouring out his heart in French. He wrote “Hungry for You (J’Aurais Toujours Faim de Toi)” for Trudie Styler, the actress he was having an affair with. The song must have eventually worked: Styler has been married to Sting since 1992. Reportedly, Sting had recently learned to play the saxophone from a do-it-yourself book, and he premiered his (modest) new skills on this track.

There’s a lot to be said for going out at the top of your game. The band’s final album, Synchronicity (1983), was their best selling and most award-winning. While it produced a pile of hit singles, including “Wrapped around Your Finger,” it’s not an overstatement to say that every track is outstanding.

Consider “Tea in the Sahara,” with its sultry, pulsing bass. Copeland’s syncopated accents on the drums and splash cymbals give this song a hint of bossa nova, diffused into a spacy coolness by the atmospheric electronic effects of guitar and synths.

And that was it for the band. Copeland and Sting were constantly at each other’s throats, and everybody had other things he wanted to do. It was time to stop. The Police took their last tour in 1986, with a brief reunion in 2007. Sting went on to a successful solo career, Copeland has focused on production and composing, and Summers is a photographer.

The Police may be gone, but you can be sure couples will continue using “Every Breath You Take” as their hilariously inappropriate wedding song until the end of time.

50 Ways to Read a Record Part 9

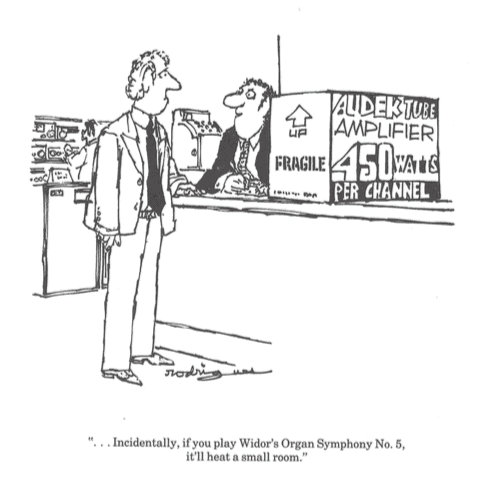

In Copper #73 we discussed an interesting but purely theoretical method of scanning phonograph records with a laser. We’re about to look at a real-world product—more or less— which plays records using a laser, with no physical contact to the groove, at all.

Almost as interesting as the device itself is the long and winding road the project has followed over the last 35 or 40 years. According to this surprisingly-thorough history from Wikipedia, about the time that the physicists at UVA were building their ultimate turntable and speculating about laser scanning of records (as mentioned last time), William K. Heine presented a paper to the AES entitled, “A Laser Scanning Phonograph Record Player”. Heine had been working on what he called the “Laserphone” since 1972, and was granted a patent for the device in 1976. As far as I can tell, Heine’s device never reached the market.

Stanford grad student Robert Reis wrote his Master’s thesis, “An Optical Turntable,” about a similar device. Wikipedia states that the thesis was submitted in 1983, which fits, given later developments—but Stanford’s own library system states the date as 1987. Oh, well. Given that Reis and fellow Stanford EE Robert Stoddard founded Finial Technology in 1983, one would bet on the earlier date for the thesis. Finial’s sole purpose was to produce a laser turntable as a commercial product.

The company’s name referred to the design or architectural element which Britannica calls “the decorative upper termination of a pinnacle”, in this case apparently meant to signify the highest achievement of record playback. The name was a problem, though, as it was often misread as “Final”, which made for any number of unfortunate jokes. But the problem of the name was nothing, compared to the problems encountered in actually producing the turntable as a commercial product.

Reis and Stoddard secured two patents (seen here and here), and managed to drum up $7 million in initial venture funding, a fair amount in pre-dot.com days, and equal to about $18 million today. Again, reports differ, but it appears that the company had some sort of presence at CES between 1984 and 1986, perhaps even each and every year. Keep in mind that timeframe: CDs were launched in 1982, and the marketplace was seeing rapidly-declining interest in analog playback—especially expensive, fussy analog playback.

Why “fussy”? Because dust, dirt, and scratches were played back as noise by the laser players. Records had to be meticulously, immaculately clean.

According to this 1989 news story, “…By 1985, the laser turntable was proven more than just “possible.” In 1986, Finial showed the first functioning prototype, and announced that it planned to have a laser turntable in the stores — possibly as early as 1987, at a price of $2,500.

“In 1987, an improved prototype of the LT-1 was shown to a very receptive group of press people at the Consumer Electronics Show. In 1988, an even more refined working prototype was exhibited at the show, but the price of the finished product was going to be higher than expected — $3,800.

“A few days before the 1989 Consumer Electronics Show, I received ‘the letter.’ It was dated Dec. 29, 1988, and read in part, ‘I regret to advise you that Finial Technology has decided not to market the Laser Turntable. This decision was made after we completed the initial production run and concluded that the unit is too expensive to produce.’ ”

So that appeared to be that. Except that it wasn’t.

Following Finial’s demise (and the loss of a reported $20 million in investment capital—$50M in today’s dollars), the company’s patents were sold to a group in Japan which called itself “ELP”—no, not Emerson, Lake & Palmer, but “Edison Laser Player”. The apparently well-funded group continued to develop the laser player for almost a decade. When it finally came to market in 1997, the ELP sold for over $20,000. The head of the group, the dapper Mr. Sanju Chiba, can be seen with the laser turntable in this video; the company’s website explains rather charmingly why the group persisted in development: “The major reason why we have been successfully overcoming every difficulties since 1989 is because of the Delightful Opinions from LT Owners.”

The current ELP LT-master.

Well, that beats $20M in investment capital, every time.

How has the audiophile world responded to the ELP? For the most part, it hasn’t. I know a wealthy audiophile in the New Jersey Palisades whose multi-million dollar sound system includes an ELP, and he loves it. Beyond that, the silence has been pretty deafening.

Jonathan Valin wrote rather dismissively about the ELP in The Absolute Sound, “…the ELP sounds exactly the same on any disc. More importantly, it makes every disc sound the same. If I were to describe its presentation in a few words, they would be ‘pleasant but dull.’ ” Michael Fremer ‘s report in Stereophile was somewhat more enthusiastic, while remaining cautious: “The overall fidelity of 78s played back with the correct EQ curve was astounding—especially an older acoustic recording of Jascha Heifetz….All of the LPs demo’d sounded open, unusually transparent, and nonmechanical, but it would be foolhardy to make any sonic judgments given the unfamiliar playback system.”

Enjoy the Music‘s estimable Dr. Bill Gaw was even more enthusiastic. He wrote in 2004, “If I didn’t have my present setup and had $11,000 to spend, I would buy this unit in an instant. During over the time I had it, I listened to significantly more vinyl than normal, as it is so much easier to use than a normal playback system.”

Today, while all manner of analog playback gear flourishes—and it is important to note that the ELP is a completely analog signal-chain, with no digital processing of the laser output—the ELP remains an outlier. When laser playback of phonograph records was proposed in the ’70s and ’80s, the process was decried as “impossible” or “too complex”. Today, with availability of all manner of expensive, exotic, tweaky record playback devices, allied with lengthy procedures and rituals—could it be that record-playing with the ELP is just too simple?

Audiophiles have been known to enjoy a hair-shirt mentality….

On a completely different wavelength (literally!) is a completely digital system. The IRENE (Image, Reconstruct, Erase Noise, Etc.) system of digitally scanning recordings, mapping them, and translating them into sound, created by particle physicist Carl Haber. The earliest known sound recordings–soot-on-paper phonautographs from the 1860’s— were translated by IRENE and heard for the very first time. The system can also be used for non-invasive scanning and playback of fragile discs, and a 3D variant is being devised to play back cylinders, amongst numerous other projects and applications.

This is truly fascinating stuff, worthy of a long look in the future.

Next time: the Vintage Whiner takes a break from phono playback.

Trade Shows

Politics.

“Roy, I need you to be on your best behavior,” said my friend Tony who worked for Epos Acoustics, an English loudspeaker company. “I’m going to bring Margaret Beckett to your room at CES. She’s here on a trade mission and I want her to meet companies that import British products

Margaret Becket was leader of the House of Commons under Tony Blair’s Labor Party government in the early 2000s.

“It’s really important that you don’t talk to her unless she asks you a direct question. The British ambassador will accompany her. If you’re on your best behavior, I may be able to get you invited to lunch.”

By chance, we were playing Beatles music when she arrived. So, I gave my presentation joking that as well as importing British Hi-Fi equipment, I only play British music on it. After the presentation, Ms. Beckett asked the usual general questions, and as the conversation was soon lagging, I asked her if she was here to meet President Bush, who had recently been elected.

“Oh no, that’s Tony’s job,” she replied. And then, to keep the conversation going, she added, “I have met Bill Clinton.” At this point, I saw the ambassador wildly gesticulating behind her. He was telling me to shut up. Unfazed I responded, “That’s nothing special, my Mother-in-law has met him twice.” She started to go red and the ambassador, glaring daggers at me, rushed her out of the room.

Curiously, I never was asked to join them for lunch.

Stupidity.

A few years ago, at the High End show in Munich, Germany, a company approached me offering me a way of connecting any of my products to the Internet. This was long before Bluetooth and Wi-Fi became ubiquitous, and although his product was expensive, the technology seemed promising, so I listened to his sales presentation.

He explained that there were five steps the end user would have to do to activate the module. This seemed a lot for novices like myself, so I suggested that he, as an obviously clever software engineer, build most of these steps into the firmware. He resisted this idea and explained that it was too complicated for him to do.

I pressed him yet again and that’s when he lost his temper. “It doesn’t matter anyway,” he bellowed at me. “You and your kind will soon be dead.”

Stupidity 2.

Stereophile, the Hi-Fi magazine, used to organize shows. The whole Hi-Fi community would exhibit, and they were perfect for networking and schmoozing. One evening, I had arranged to take out a bunch of the magazine’s reviewers for dinner. It was a good group, comprised of John Atkinson (still the editor), Michael Fremer (still the analog guru), my friend Bob Reina (now sadly deceased), Wes Phillips (also gone), my sidekick Leland Leard, and I think one other journalist. We went to a restaurant in Los Angeles called AOC and had a really good meal. We also drank a lot of wine. At the end of the evening, I asked for the check. I expected it to be expensive and it was. The bill read $840, so I added approximately 20% to the bill, as a tip, and rounded the charge up to $1000. We went outside to wait for the taxi and as it had not yet arrived, I went back into the restaurant to use the toilet. My waitress, on seeing me, came over and thanked me gratefully for the generous tip. I told her it was my pleasure and that we all had a great time.

The next morning, Leland and I went out for breakfast. We were staying in Manhattan Beach and walked down towards the sand. We found a restaurant and ate breakfast outside, enjoying the bright California sunshine. When the bill arrived, I took out my credit card to pay and wrapped around it was the receipt from the previous evening. I opened it up, read it, and started laughing. In the restaurant the previous night, the lighting was dim but in that sunlit morning, everything was crystal clear. I looked at the total and the amount read $640. I had given the waitress a $360 tip. No wonder she thanked me so profusely.

What to do? Nothing. I reckoned that both of us got a good story out of my mistake.

Keith Richards Will Still Be Here When You Are Gone

This article is about preservation. No one exemplifies this more than the legendary Rolling Stones guitarist, Keith Richards.

Oh, sure, his survival despite years of damage from drug and alcohol use, is as startling as it is humorous. I’m using Keith here simply as a reference that very quickly and cleanly brings a visual into focus in your mind.

Preservation, in my case, covers a variety of subjects: my own body, my guitar collection, my record collection, my Beatles memorabilia collection, and by extension all things emanating from the sixties that tell the story of not only my teenage years, but the incredible period of time (cultural as well as political) that I had the great fortune to grow up in.

It begins not as a preservation story, but as an acquisition story. After all, before you can preserve you have to collect and/or obtain.

Why I thought that what I was living through needed to be to catalogued for the future, is the most intriguing question. I can clearly remember saying to myself, as I was attending one of the dozens of legendary live shows at the Fillmore East concert hall in Manhattan, that what I was watching was going to be talked about in 50 years. That’s why I kept all the Fillmore programs. That’s why I kept all my R. Crumb comics. That’s why I kept newspapers and magazines on the dates that mattered, like the Kennedy and King assassinations, the moon landing (on my birthday no less), Nixon’s resignation, the end of the Vietnam war….

I also kept the paperwork relating to my lawsuit against the NYC Board of Education for violating my constitutional rights for preventing me from handing out an underground newspaper, as well as my pretty horrible report cards.

I have extensive guitar and vinyl collections, as well, which are pretty awesome, if I do say so myself.

The guitars and the albums are always maintained.

Here is what it’s like to preserve and play an album in my house:

I have a record washing machine that I use before I play an album. It takes 6 minutes to wash one. My wife has no patience for this, which is why God created Sonos. When she wants to hear a song, she can push 2 buttons on her phone and have it instantly. Me? After a 6-minute record wash, I then place the album onto the turntable, make the speed adjustment from another piece of gear that controls the motor, set the preamp, the “phono,” and place not one, but 2 record weights on the turntable to stabilize the record so that the needle can pick up everything.

It takes about 10 minutes just to get to the point of placing the tonearm to the album, and since many of my reference albums have been remastered at 45 rpm, not 33, you only get about 14 minutes per side.

Oh, and did I mention the record washing machine cost $4,000, the turntable cost $21,000, the phono cartridge cost $6,000, and the phono preamp that allows the cartridge to connect to the stereo cost $13,000?

That’s over $40K before the cables and power cords. Not to mention amps and speakers….

Why?

One can play an album pretty quickly and pay a whole lot less— like, say, $200!

I have been into vinyl as a music medium since I was 10 years old, and have followed its playback evolution for the past 60 years. Even after the CD was introduced in 1982, I just knew that vinyl was always superior sounding and the artwork with the album was an art form that could stand on its own.

There is a New Yorker cartoon floating around the internet in my hi-end audio world which shows 2 record collectors admiring a stereo owned by one of the 2 guys. The caption reads:

“The two things that really drew me to vinyl were the expense and the inconvenience.”

Beethoven’s Last Christmas

In 1825 and 1826, Ludwig van Beethoven was nearing the end of his life. He had fallen ill, was bedridden for over a month, and clearly felt his end was near. But he recovered, and almost in a spirit of gratitude for having being spared, set about composing his Late String Quartets, Nos. 13 – 16, including the Große Fuge, his last known composition. These extraordinary works are widely considered to be among the greatest compositions of the classical period, yet left the wider audiences of the day confused and bewildered. Even so, Schubert himself asked for the Große Fuge to be the last musical work he heard. It duly was … and he declared: “After this, what else is left to be written”.

Following this creative spurt, Beethoven took ill again in December of 1826, and remained weak and bedridden until he passed away on March 26th. This, in summary, is the official history of Beethoven’s “late period.” But was there more to it than that?

Beethoven’s Große Fuge was originally written as the last movement of his 13th String Quartet, but at its first performance audiences found it to be too long, too heavy, and altogether quite incomprehensible. Beethoven thought otherwise, and decided instead to use it as the cornerstone of a tenth symphony, one which would explore musical themes and ideas that would really push the boundaries of what was going round and round in Beethoven’s deaf, yet explosively creative head.

Over the summer and autumn of 1826, a five-movement tenth symphony began to come together. The Große Fuge was originally conceived as as the finale, but as the symphony took shape it was moved from the finale to one of the inner movements, orchestrated for string orchestra only. But he just couldn’t make it fit in with the ideas of the symphony he was constructing around it, and eventually he stopped trying to force it, and published it in its final form as Große Fuge, Op. 133.

Meanwhile, the tenth symphony was really progressing well, and if the original Große Fuge received a lukewarm reception in its incarnation as the finale of the 13th String Quartet, it became clear to Beethoven that this tenth symphony would not be welcomed at all. It really pushed the boundaries of tonality and sonic texture. It employed unusual harmonic progressions and rhythmic extremes that would not again see the light of day until Stravinsky. So Beethoven, even on his best days a disagreeable and irascible personality, determined that he was not going to publish the symphony at all. He had more or less completed the draft score, and wrote over many of the pages how the critics were incapable of understanding true music, and how they were going to go to their own graves, denied the privilege of listening to the greatest of Beethoven’s works.

What Beethoven’s ultimate plan for the symphony was – if any – remains unknown, as his final illness prevented him from executing it, and he declined to leave any instructions acknowledging it. It seems that he was indeed desperate to keep it from his publishers, as he instructed his housekeeper Sali (Rosalie), to keep it hidden from them in the event that he passed away. It is likely he was just being bloody-minded, and had no actual long-range plan at all.

Beethoven had notoriously abusive relationships with a string of housekeepers, of which Rosalie Schott (or Schutz) was the latest. She had an older brother Hubert who worked for one of the publishing firms Beethoven had done business with. Hubert Schutz (he went by Schott later in life, but appears to have been known as Schutz at this time) had heard from his superiors that Beethoven needed a new housekeeper, and suggested to his younger sister that she apply for the position.

At some point it became clear to Sali that her master was not going to recover, and that among his papers nobody but her knew anything of the manuscript for the tenth symphony. And, shortly before his death, she took the manuscript home. Maybe she had nefarious intent, or maybe she was just following her master’s instructions…we can only speculate. But on March 26th, 1827, Ludwig van Beethoven died, which was a huge event in Vienna, but to Sali’s delight the dust cleared with nobody looking for a tenth symphony.

By this time, Hubert Schott had taken a position with another publishing firm in Graz. Rosalie sent him the manuscript of the tenth symphony, suggesting that Hubert publish it and share the profits with her. But Hubert was horrified by the idea. He felt he had no plausible rationale to explain away his being in possession of an unpublished tenth symphony by the great Ludwig van Beethoven without it reflecting badly on him, let alone how he might profit from the endeavor. By all accounts, he was still no more than a clerk.

At this point, Rosalie disappears from history, and nothing more is known of her, or what became of her. The same would probably also be true of Hubert, except that he proved to be a diligent employee, and by 1861 he emerged as the owner of the music publishing firm H. Schutz of Graz, Austria. The firm, and its owner, had evidently enjoyed some modest success, and Hubert appears to have moved into an address in Kärntnerstraße, Graz, quite a prestigious address at the time. The Schutz family continued to occupy the Kärntnerstraße residence until only an aged spinster remained. When she passed away at the end of WWI, Julius Lichtensteiner moved in and raised a family there, including a grandson Jakob.

Eventually, Jakob inherited the property, and he continued to live there until his retirement in 1991. The property at Kärntnerstraße is (or was … I don’t know if it still exists) too large for him to manage, and he decided to move to a cottage in the countryside. As part of the process, he cleared out the attic, and among the junk he found a leather satchel containing sheafs of old music. For reasons that remain unclear, he decided to sit on this for a few years before he took any notice of what it was. But eventually, he set about examining the musical contents. Jakob was not at all musically inclined, so he could not make anything of the music itself. But after a while, he learned to decipher the scrawled handwriting, and realized that what he had on his hands was something by Beethoven, and whose title was, evidently, “X. Sinfonie.” Even Jakob Lichtensteiner, uneducated as he was in the history of music, realized that a tenth symphony of Beethoven was potentially a very hot property indeed.

Now, you would have to have met Jakob Lichtensteiner – which I have – to understand what followed next. Jakob was one of those people we have all met from time to time. He was basically a clever man, but one who over-estimated his own intelligence. At the same time, he was pathologically suspicious of the motivations of others, while consistently managing to under-estimate their abilities. So, he lived in a permanent state of having tremendous, yet devious plans, which he had no intention of sharing with anyone who might want to steal them from under his nose. Yet, at the same time, you could read him like a book. He must have either earned a tidy sum of money along the way, or inherited it, because he was clearly comfortably off. He chain-smoked, yet was defiantly tee-total.

So where do I come into this story? At that point in time I was still laboring under the youthful delusion that I could be a composer. I was a bit of a computer whiz (for that time, anyway) and I decided that rather than a lack of talent, it was the need of a software suite called Sibelius that was standing in the way of my musical ambitions. So, I bought and installed Sibelius, and a midi player. As a result, I could simply type a musical score into Sibelius, and have the sounds of a synthesized (or sampled) orchestra come out of my speakers. I thought it was just the bee’s knees.

I was doing mostly R&D in semiconductor lasers, and spent a lot of time attending international technical conferences. As part of this I got an invitation to a highly prestigious conference called the “Snowbird Conference,” an invitation-only event in Snowbird, Utah. At this conference, the technical and networking sessions are carefully organized to leave plenty of time for skiing. So, I met a lot of new friends, and did a lot of networking. In particular, I got on very well with an Austrian researcher, Jerome, who was a seriously expert skier, and he guided me through some scary trails that I normally wouldn’t have gone near. In the evening we sat in a hot tub, on the roof, in 3 feet of snow, and I told him all about Sibelius, how you could just enter all the instrumental parts from an orchestral score into it and hear it as it would actually sound played by an orchestra.