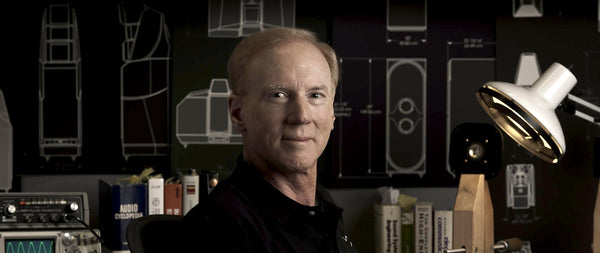

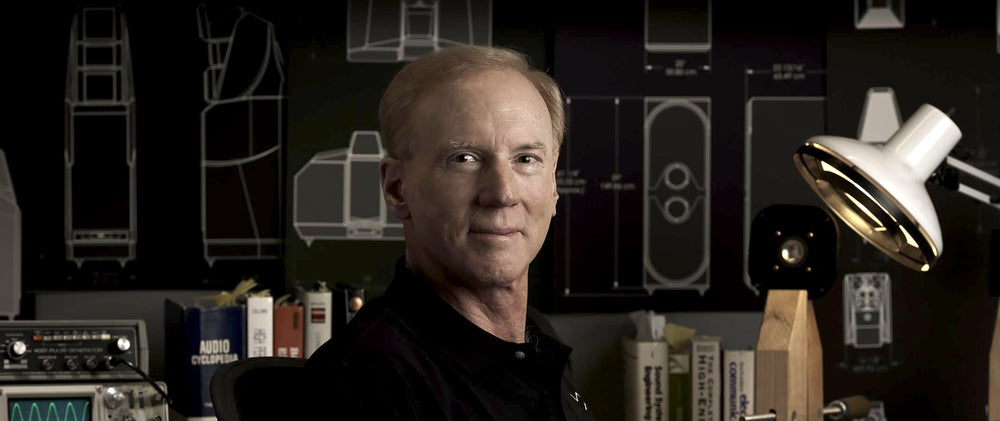

Cairo-born Kamel Boutros is a modern New York City Renaissance Man. As an internationally acclaimed opera baritone, he has performed baritone roles in multiple seasons at the Metropolitan Opera in New York under the baton of James Levine, Gergiev and others, as well as in the UK, Japan, India, Italy, France, and in other countries. He has shared stages at the Louvre in Paris, Bepu-Japan, and Verbier with his close friend, piano virtuoso Martha Argerich , the late Luciano Pavarotti, Tony Award winner Ruthie Ann Miles, and many others. As an actor, he has appeared on the New York Off Broadway stage in Babette’s Feast and in award winning independent films and television shows, including major roles as 9/11 terrorist leader Mohammed Atta in The Hamburg Cell and as Mahmoud in The Death of Klinghoffer. He has also arranged music for film and television shows, such as Damages.

A superb classical pianist, he currently is the Music Director of Calvary – St. George’s Church parish in Gramercy Park, New York City, where he programs, conducts, writes and performs an extraordinarily broad range of sacred music from multiple nations and genres composed over the last five centuries. Calvary – St. George’s Church has had the benefit of Kamel’s reputation over the years to bring an incredible array of guest musicians and singers from many cities and countries into its parish for exciting renditions of anything from a Bach oratorio to a Haydn symphony to a Bahamian Christmas carol to Middle Eastern music featuring the oud, to Americana and gospel hymns to contemporary electric worship music.

Kamel also supervises all of the audio and co-manages video production at both churches, which are historic landmarks in New York City. (St. George’s Church was founded in 1749; Calvary in 1832.) With pipe organ repairs and maintenance slowly going the way of the buggy whip, Kamel innovated a number of custom digital modifications to Calvary’s ancient pipe organ in order to stave off its obsolescence and incorporate it into his MIDI keyboard and pedals setup along with his Yamaha Concert Grand piano.

Kamel took some time from his busy schedule to discuss his childhood growing up in Egypt, his musical journeys and his work both on the international stage as well as in the church with John Seetoo of Copper.

J.S.: You are known in many musical circles for your humility and eclecticism, as well as a love for improvisation – all traits not immediately associated with classical music, at least from this rock musician’s experience. Where does this wide open music sensibility come from? Did your experiences growing up in Cairo help to shape your current attitudes towards music?

K.B.: I actually had no prior idea about improvisation. There isn’t any word in Arabic for “improvising.” The closest thing is the word “Taalif”, which mean “composing”, but also has some negative connotations since it can also mean “lying”. (laughs)

My mother, Nelly Boutros, was a trained classical pianist. As a matter of fact, when she was 8 months’ pregnant with me, she played Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto – not an easy piece – for her graduation exam at the Cairo Conservatory. However, I never heard her play at home except when was giving a few lessons, or playing hymns. Her main job was accompanying dancers at the Ballet Conservatory.

(Kamel explained that both conservatories are part of the Higher Institute of Music Learning in Cairo.The Conservatory is where she would take Kamel every day as an infant, so he was hearing so much music from the windows of the Conservatory of students practicing. It was one of Nelly’s colleagues who was tossing Kamel up into the air and once not catching him where Kamel fell head first on the floor. Kamel jokingly believes that that is when music came into his system – head trauma and hearing all these different instruments practicing – along with the guy shouting advertisements for his cold sugar-cane juice.)

My first exposure to non-Arabic music and to harmony was the movie, The Sound of Music. Since Arab music is diatonic, the harmony voices and the soundtrack blew me away as a kid. That was the turning point. The first song I ever played on the piano was “Do, Re, Mi” when I was 3 years old. There was a stain on the Middle C key and that’s what I looked for as my starting note.

Growing up attending a Presbyterian Church in Egypt, I would watch the organist in the chancellery and I was mesmerized! It was like watching a film – seeing the hands at the keys and the knobs, feet on the pedals – it was my dream to play the organ.

J.S.: What musical training did you have to undergo in Egypt to gain admission to the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia? What was that experience like?

K.B.: I never had much training in Egypt. Learning basics at the church, I wasn’t aware of it but I guess I progressed very quickly. When I was 11, the church asked me to play a John Peterson Cantata because they needed someone with the skills. At home in Cairo, we had a horrific upright piano, which is still there, and hardly ever tuned, and could not be played in the evening without disturbing the neighbors. I looked at this piece and I realized that I had to practice it, and I needed a keyboard where I could plug in headphones for silent practice.

There was a Yamaha keyboard at a music store that compared to now, wouldn’t even be a decent toy, but at the time, I needed it, but my parents absolutely refused to spend the money. The only time in my life I ever stole – I snuck into my parents’ room and stole 500 Egyptian Pounds to get that Yamaha so I could practice. I was beaten after they found out, but it was worth it, and of course, I eventually paid them back. I now own a Yamaha 6’4” grand that I use at Calvary and I have a 7’4” Yamaha at a friend’s place where I get to play it.

My formal music education started when I was 13. An Egyptian family in Boston that was connected to the church brought me to the Lexington Christian Academy on a scholarship. Even there, the choral teacher would ask me, a foreign student, suggestions on exercises for the class. I felt like I had to play along, but I think that whatever improvising talent I had made the teachers assume that I knew more than I actually did, so I went through school with what I feel are gaping holes in my knowledge to this day.

At Curtis, I really looked up to Edward Aldwell. One day, I had a chance to play the Steinway B alone and after about 20 minutes, I saw a face in the door window, and it was Mr. Aldwell. I stopped playing, and he asks me what composition I was playing. I told him I was just making it up. He looks at me shocked and then gives me a hug, saying, “We have to do something about this.” The keyboard harmony teacher tells me to not bother coming to class. At the end of the semester, he gave me a F. I asked him why and he replied because I didn’t show up. I reminded him that he told me not to, and then he remembers and changes it to an A, telling me “Don’t slow up!” In retrospect, I think I have chunks of musical vocabulary missing since I can’t explain much of what I do, and it’s a struggle for me when conducting at times.

Improvisation, what I call playing “unbrained” – is not a conscious thing. The piano can be wonderful and evil at the same time – it’s a very needy wife. If you don’t touch it at least once a week, your fingers and brain don’t quite connect. Because I played in church, nothing else was needed. But later on, the gaps of knowledge still come back to bother me.

J.S.: You have performed Carmen, La Boheme, Romeo and Juliet, Madame Butterfly, and many other opera standards at the Metropolitan Opera, as well as solo pieces with orchestra, such as Bach’s St. Matthew’s Passion. What inspired your love of opera and what do you look for in a musical piece to motivate you to devote the time to add it to your repertoire?

K.B.: For me I look for when a composer can cry a melody that matches with the words. It has to grab you emotionally first, then intellectually, like Rachmaninoff! Not small breaths, but big breaths. Good music will make you scream and cry. I don’t have to talk about good music; bad music – you have to talk about it. (Because the emotional connection was lacking.)

J.S.: Your close friendship with Martha Argerich is probably best exemplified by one of her visits to New York for a Carnegie Hall performance, where she stayed with you as a houseguest and willingly prepared for her concert on a plastic Casio keyboard and insisted that you use your Yamaha Concert Grand to rehearse the Calvary Church choir. How did you two meet, and what is it like when you play together?

K.B.: Actually, that was before I was at Calvary. I was singing at the Met and I was living in a small apartment in Inwood at the time. The head of the opera department at Curtis named Mikael Eliasen took me to Carnegie Hall to listen to Martha Argerich play at Carnegie Hall. I had never heard her live She played Prokofiev’s Third Piano Concerto and it literally changed my life! She was musically on fire! I instantly became a huge fan and followed every bit of news about her. I couldn’t believe that her phone number was listed in the Musician’s International Directory. I called it and her voice mail message in French said to leave a message or a fax. I had read a news article that she was ill, so I sent her a fax telling her to take care of her health. We eventually met in Switzerland and now we are all like an extended family.

(One of her daughters, Annie Dutoit,has now become an actress. She and Kamel are planning a few film/music projects that will involve Martha at some point!)

She’s so down to earth. When Martha was coming to New York, I jokingly suggested she should stay with me. She said yes, and right away I said “I’m poor!” She didn’t change her mind. She was impressed that I could drive – I had a seriously beat up Toyota that was donated to me from a church I was helping in NJ, but she didn’t care. When we got to my building she asked which button to press on the elevator, I told her 2nd floor. She said, “Normal.” I laughed like mad. She was used to 50th floor fancy hotel suites but actually wanted something real. She actually gets upset when people applause before she even plays. “Are they applauding for me? They don’t know me; I haven’t even played yet! Why are they applauding?”

J.S.: Keeping it real?

K.B.: Keeping it real. And she’s so…unpretentious, it’s wonderful. Another time, she showed up to surprise me at Calvary during a service and wound up playing. I was at the organ and starting the second hymn, and I smelled her perfume – it’s Shiseido. I turned and she was waving at me. I was in shock! She got up and started turning my pages for me, of all things! People in the congregation who recognized her started texting their friends: “Martha Argerich is at Calvary!” She later played an impromptu set with me. One of the choir members who is Argentinian burst into tears and couldn’t sing; ten feet away from her was one of the most famous Argentinian musicians in the world acting like a normal person! Through the years I have become friends with some well known people in music, film and the arts. And I’m just blown away by the ones that knew that fame is not real, comes and goes. Nimet Habachy, Rachel Ticotin, Tony Hale, Peter Strauss, Sandy Faison, Todd Sussman, Fred Rogers (Mr. Rogers), Rev. Timothy Keller (whose preaching changed my life!).

J.S.: What prompted you to step into the theater and film worlds in addition to your many musical accomplishments? What are your favorite moments from being an actor and a film and video producer so far? Is film and music scoring a field you plan to pursue further?

K.B.: I had never thought about acting in films. John Adams’ Death of Klinghoffer was the first film I was in; it was a film version of the opera. I was asked to come to the UK for the audition and couldn’t make it, so I sent a video instead of me speaking into the camera. For some reason, it impressed them enough to send a plane for me to meet with them and they wanted me to play the terrorist. Klinghoffer’s choruses was what attracted me – there are two: one with Palestinians and one with Jews – that are just glorious! And he even used synths! Who is this man?

Klinghoffer was also my first time working with a living composer. There was one part where I was holding a Kalashnikov and I decided to change a part slightly and add “Sika” which is an 8th tone aspect of Arabic music that “adds the crying” to the melody. Adams came up to me and I thought he was going to be furious for changing his music, but instead he hugged me and insisted that whatever I was doing to keep doing it! For other film parts, the casting agents came to me; I didn’t pursue them. I’m not as interested in acting as I am in music.

My Requiem, which debuted in Paris at La Madeleine in Paris, was my first large scale orchestral composition, and almost was cancelled because the Brussels bombing occurred earlier that day and it wasn’t until 3pm that we knew whether or not the French police would let the show go on. It had an all men’s chorus of Christian, Jewish and Muslim singers with a soprano, Tami Schuch-Yaegashi, who sang in English, Arabic and French. They wouldn’t let me use the big Bonaparte organ that Gabriel Faure used to play. La Madeleine is huge and has like a 3-4 second echo. Thinking back, I should have redone some of the parts because of that echo on the syncopated parts. The Requiem ends with the line, “That is how much God loved the world (you and me) that he ‘discarded’ his only son so that those who believe in him will not suffer, but have absolute eternal life”

But yes, I’d like to do more scoring and my dream is to write song stories. My next composition will be an opera of a fictional dialogue between God and a suicidal man.

J.S.: Basically, opera.

K.B.: (laughs) – Yes! Opera!

J.S.: As you work in a variety of musical genres, do you have a different approach and system for your methodology in handling and conducting a classical symphonic piece for an orchestra vs. a jazz, rock, or world beat ethnic instrument music arrangement? I know that when I have had the fortunate opportunity to play with you, you gave me fairly wide berth with my guitar, bass, lap steel and dobro parts when doing Americana and contemporary worship music.

K.B.: Conducting is very overrated. An amazing conductor discovers what people in the orchestra have already, not just a bucket of his own ideas, and not 80 slaves with instruments. A good conductor finds where the weaknesses are and works with them. He or she should be like a psychiatrist or a record producer. Once the homework is done, all the glory can shine through. Certain musicians can inspire the rest. A violinist was playing a part with Martha. Instead of responding with the piano part softly as written, she attacked the part and changed the tempo, which fired up the violinist to respond. Creating a chance to capture those moments is what should be the goal. 30% will love it, 50% will hate it, but it can be magic.

J.S.: As Musical Director for a centuries’ old Episcopal Church, how did you become involved with Calvary – St.George’s parish, and what are some of the challenges that you faced? Were there any cultural clashes between your secular music and art background, your Middle Eastern upbringing, and the Anglo based western Christian traditions?

I was actually asked by the then Rector of Calvary to take that job while I was still singing at the Met. I decided to take the job since I needed to show (employment) stability because it would give me the ability to bring my mother and brother to the States. Musically, it was a new culture: the church calendar, the liturgy…in Egypt, hymns were chosen to reflect on current events, which could involve war, or food shortages…at Calvary, it’s forbidden to sing “Alleluia” during Lent, so it’s a whole different thing. At first, I saw them as limitations, but now, I find it freeing. A nice picket fence, rather than a prison. That difference can make Episcopal prayers seem disconnected to the world, but in another view, it keeps the focus on God. Bad stuff will always happen but Christ’s love is constant. Music helps to keep that connection. Tim Keller (of Redeemer Church) changed my life with his explanation of the Prodigal Son. That (revelation) started my new Christian life.

J.S.: Calvary St.- George’s Church’s reputation for eclectic music programs has been cemented by the various secular singer songwriter, jazz and classical concerts produced at both church locations in conjunction with jazz trumpeter Alex Nguyen, whom you have handling music services at St. George’s when you handle duties at Calvary. What has motivated you to expand musically in all of these directions through the church, and do you see it as a kind of music ministry, such as with Mockingbird? (Mockingbird Ministries was founded by David Zahl in 2007 while in NY and as a regular attendee of Calvary Church.)

K.B.: I’m somewhat conflicted with music programs tailored to bring people into the church. Admiring music in concert spaces is ok, but for a church, it can be dangerous. The focus should be on the worship, and that has to start pastorally. Luckily, Jake (Rev. Jacob Smith, current Rector of Calvary – St. George’s parish) is very good at bringing us all to a worship place so the music can make that connection.

Alex has done an extraordinary job; there’s not a jazz musician in New York that doesn’t know about the Jazz Vespers services at St. George’s. But music alone won’t bring people to faith.

J.S.: Looking back on your career and musical journey so far, what would you say were the highlights and the most regrettable moments?

K.B.: Highlights? Singing at the Met with James Levine, Pavarotti, at the Louvre and elsewhere with Martha, of course…and my long friendship with Fred Rogers. He was a relative of my roommate at Curtis, Alan Morrison, who is a wonderful organist. Fred Rogers became an admirer of my playing and had tapes of my improvisations. We kept up a written correspondence. I didn’t even know he was a TV star or what the Mister Rogers show was!

Regrets: Being admired to the point where teachers I sought thought there was not much to teach me. I have ADD, which gets worse with age. I have a fantasy about starting my musical studies all over from scratch. I have degrees from institutions that I really feel I don’t deserve.

J.S.: Looking forward, what projects are you working on and what are you looking to accomplish in the next five years or so?

K.B.: I want to learn and master computer music software of all types to get to the point where I can produce and compose as quickly as I can improvise ideas in my brain. I love listening to all music – I can always find something. Even rap – the production and engineering on some of those records are out of this world!

J.S.: Out of all of your various activities, which would you say have been the most fun and the most satisfying?

K.B.: I think the most fun and fulfilling was seeing people touched by my music. I set “Come Ye Sinners” to original music I wrote and tried to do it justice. When I was in Paris, a French and Arabic version was performed and I saw people crying. It was one of my most elevated musical moments from the outside in. I started crying myself and said to God at that moment: “OK, so I’m not a useless piece of ***t, just annoying creation by being here!”

(A separate article on the digital innovations created by Kamel Boutros to customize Calvary Church’s ancient Aeolian-Skinner pipe organ will follow in issue #61 of Copper.)