In Issue 162, I talked about Nick Drake, the artist and musician, and the myriad of mysteries surrounding his brief lifetime here on earth. This go-around, I’d like to touch on his three catalog albums in the form of the 24-bit/96 kHz digital downloads that are currently available just about everywhere. As I mentioned in the last issue, if you were lucky enough to have purchased one of the Universal Music Back to Black series of Nick Drake reissue LPs in 2013, then you could easily have gotten the 24/96 downloads for all three albums at no charge. That was definitely an opportunity I missed out on – well, the best things in life aren’t always necessarily free!

In 1965, Joe Boyd was working as an assistant to Jac Holzman, head of Elektra Records, and Holzman had an idea that would save him money in the recording process. Many of the records Elektra was producing required strings and orchestrations, and English orchestral musicians were not only better players than their American counterparts, but they’d also work for less money. Holzman sent Boyd to London to scout not only musicians, but also potential recording locations, and his good fortune led him to engineer John Wood at Sound Techniques studio in Chelsea. The studio was perfect for his needs, and Boyd soon immersed himself in the London pop and folk music scene. In no time at all, he’d abandoned the Elektra gig, formed his own production company (Witchseason) and was working full-time producing artists like The Incredible String Band, John Martyn, Fairport Convention, and Richard Thompson. He recorded them all at Sound Techniques, and even recorded Pink Floyd’s first singles at the facility.

There are conflicting versions of how Nick Drake came to Joe Boyd’s attention in 1967. One recounts how a Cambridge friend of Drake presented Boyd with a demo tape, and another claims that Ashley Hutchings of Fairport Convention (who was apparently quite taken with Nick Drake) called to insist that Boyd meet him. Regardless, Joe Boyd offered Nick Drake a recording contract after hearing that demo tape; the songs were very well-crafted, and showed a level of maturity and sophistication that was uncommon for a folk artist of the day. Drake’s intricate fingerpicking style and complex tunings were also unlike anything Boyd had ever heard. That four-track demo tape became the basis for Drake’s first album, Five Leaves Left.

I recently added Gustard’s X26 Pro (their top-tier DAC) and C18 Constant Temperature Master Clock Generator (also top-of-the-line) to my system. The result has been a serious uptick in the realism and musicality of my digital playback, and has significantly enhanced my enjoyment of these three outstanding albums, which have never sounded better in any digital format. Nick Drake’s music could possibly be considered something of an acquired taste, and it’s not always the most upbeat or uplifting, but it’s extremely poignant and thought-provoking. And well worth a listen.

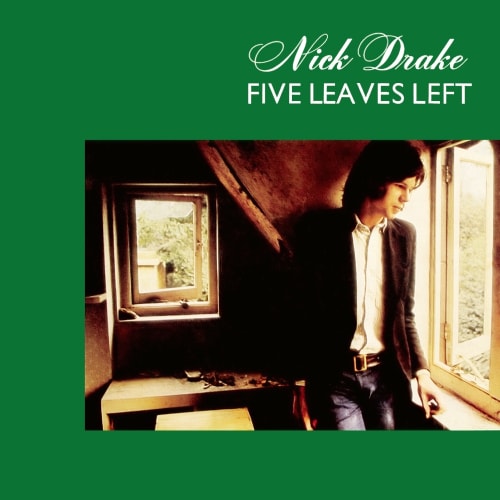

Nick Drake – Five Leaves Left

Joe Boyd’s connections with the diverse group of artists he’d been recording at Sound Techniques made getting musicians to back up Nick Drake on Five Leaves Left easy. The core group he assembled in July 1968 included bassist Danny Thompson and pianist Paul Harris, with Nick Drake’s own astonishing acoustic guitar work and vocals providing the centerpiece for all the songs. Even Richard Thompson came by, to provide the quirkily effective electric guitar on the lead track, “Time Has Told Me.” By all accounts, the studio experience was a good one for everyone involved, and Drake was easygoing and professional in his interaction with the other musicians during the sessions. The album’s title, Five Leaves Left, referred to a printed note inside the old Rizla cigarette paper pack, which stated that there were “only five leaves left” in the packet. Drake was apparently smoking a lot of weed at the time, which helped suppress his anxiety in the studio.

While most of the songs were instrumentally sparse, many featured string arrangements, and Boyd had gotten highly-regarded arranger Richard Hewson to provide the orchestrations. However, following the first rehearsal to feature strings, Nick Drake expressed his discontent, insisting that he be allowed to bring in his own arranger. Drake’s choice was an associate from Cambridge, Robert Kirby, who had no professional recording experience, but had orchestrated some engagements for Drake at school. Needless to say, both Joe Boyd and engineer John Wood were less than ecstatic about this turn of events, but after Kirby’s first day on the job, he was offered a contract for the duration of the album. Contract in hand, Robert Kirby left Cambridge forever the following day. According to John Wood, very few overdubs were employed in the recording process, and Nick Drake essentially played live with the session musicians and string ensemble in the studio. This probably helped contribute significantly to the shockingly good sound quality of Five Leaves Left. The use of strings throughout adds to the mood of the album without in any way overpowering the delicate instrumentation or Drake’s seemingly fragile voice.

The songs on Five Leaves Left are very strong, and offer a surprisingly entertaining mix of captivating tales and droll encounters, all delivered with Drake’s signature, soft-spoken, almost whispery vocal approach. The overall effect of the music is stunning to say the least, and the often uplifting nature of the songs downplays Drake’s reputation as the “patron saint of the miserable.” I’ve listened to this album literally countless times over the last couple of decades, and I can honestly say, there’s nothing else in contemporary folk-rock music from 1969 – or any other period, for that matter – that even remotely compares with it. Drake basically lays it right out there on the opening track, “Time Has Told Me,” when he sings, “Time has told me…you’re a rarer find…a trouble cure…for a troubled mind.” He’s telling us, “I have issues,” but he also seems upbeat. Whomever he’s singing to may have their own set of problems, but they’re also definitely helping him with his.

Up next is “River Man,” the song Nick Drake considered the very heart of Five Leaves Left. The mood here is almost mournful, but it’s easily the most powerful song on the entire album, despite the totally cryptic lyrics. “Gonna see the river man/gonna tell him all I can/about the plan/for lilac time” – I can’t begin to tell you how many times I’ve dodged questions from my teenage daughter while this tune was playing, with “What does he mean about lilac time?” That exchange has morphed a couple of decades later. Now, anytime I question her thirty-something thought process, she responds with, “You figure it out, Dad. It’s lilac time.” I have since determined that “lilac time” is a very British thing that symbolizes Spring and renewal, so maybe it was never quite as cryptic as I once thought.

That somber mood continues throughout what would have constituted side one of the LP. “Three Hours” is the album’s longest song, and recounts a particularly harrowing journey. Next up is one of Nick Drake’s most frequently-quoted songs, “Way to Blue.” “Don’t you have a word/to show what may be done/Have you never heard/a way to find the sun?” Drake is looking for that ray of light in his existence, but it obviously continues to elude him. “Day is Done” contains some of his finest fingerpicking on the entire album, but the song espouses a constant theme of Drake’s music: his inability to make any progress in his life. Side two is significantly sunnier in outlook, with uplifting tunes like “Cello Song,” “The Thoughts of Mary Jane,” and one of the album’s real highlights, “Man in a Shed,” where Drake engages in a raucous banter with a presumed love interest.

But the sunniness of that progression of songs comes to a screeching halt with perhaps the most poignant and strangely prophetic song of Drake’s entire catalog: “Fruit Tree.” The song basically outlines the tenet that many artists never receive any recognition for their work until long after their deaths. Again, this is particularly rare territory among folk singers of his generation – how many songs can you point to from that era where singers embraced the reality of their own impending doom, especially at age 20, when Nick Drake wrote the song? “Fruit Tree” really resonates with me at my current age, but I can’t imagine it would have made the same impression on my much younger self.

“Fame is but a fruit tree…so very unsound

It can never flourish…‘til its stock is in the ground

So men of fame…can never find a way

‘til time has flown…far from their dying day

Fruit tree, fruit tree…no one knows you but the rain and the air

Don’t you worry…they’ll stand and stare when you’re gone

Fruit tree, fruit tree…open your eyes to another year

They’ll all know…that you were here when you’re gone.”

The album closes with “Saturday Sun,” which includes a really nice drum and vibraphone accompaniment that differentiates the song from anything else on the record. Nick Drake contributes his only turn at the piano on the album here, and his playing is beautifully effective. The song’s relatively sunny outlook helps bring the album to a positive close and diffuses the overwhelming melancholy of the preceding “Fruit Tree.”

The 24-bit/96 kHz tracks here – in my humble opinion – present Five Leaves Left in the absolute best sound the album has ever displayed in any digital format. I’ve read that at the time of its remastering, the original analog tapes were in very poor condition, and extra care was taken to preserve them as best as possible digitally. It appears to me that Universal did indeed accomplish that here; the sound quality is absolutely superb, with virtually no tape hiss apparent in any of the tracks. That’s probably also due in part to many of the tracks being recorded essentially live in the studio. The album displays very good dynamic range for a recording that’s over fifty years old; I feel that the sound quality betters any of my CD or LP versions, whether on the Antilles label or the Universal reissues from 2013. This album comes very, very highly recommended. Many of the songs will still resonate with contemporary music audiences. If you have any appreciation at all for English folk/rock from the late 1960s/early 1970s period, it’s a must-listen.

Island Records (Universal Music), CD/LP/download from HDtracks (24/96) – Available for streaming on Qobuz, Tidal, Amazon, Pandora, Deezer, Apple Music, Spotify, YouTube

Nick Drake – Bryter Layter

Despite Nick Drake’s reportedly disastrous Royal Festival Hall appearance in late 1969 as one of the opening acts for Fairport Convention, producer Joe Boyd saw the failure of Five Leaves Left as an aberration of sorts, and was keen to get Drake back into the studio for his follow-up record, Bryter Layter. He assembled his crew at Sound Techniques Studio again, this time adding both Dave Mattacks (drums) and Dave Pegg (bass) of Fairport Convention to the proceedings. Richard Thompson again makes an appearance, adding the lead guitar to “Hazey Jane II.” Drake was reported to be a fan of the Beach Boys (!) album Pet Sounds, and two regular session musicians for the Beach Boys, Ed Carter (bass) and Mike Kowalski (drums) were recruited for Bryter Layter. None other than John Cale of the Velvet Underground adds viola, harpsichord, piano and organ to several songs. And Ray Warleigh’s sax and flute turns on many of the songs add a jazzy feel to the album, giving it a very different overall vibe to that of Five Leaves Left from just a year earlier. Robert Kirby was again called upon to provide the string arrangements, and the sessions got underway in early 1970. Bryter Layter was originally scheduled for a November, 1970 release, but disagreements over the album cover artwork delayed it hitting the record stores until March 1971.

Keith Morris’ iconic photo of Nick Drake that graces the cover of Bryter Layter has Drake almost completely shrouded in shadows. While this was eerily prophetic of Nick Drake’s personal psyche and eventual path, the album is much more polished and upbeat than its predecessor, and is easily the most well-orchestrated of Drake’s brief career. That said, it’s easy to gather from Joe Boyd’s recollections of working with Nick Drake that he was already on the downhill side of his spiral into illness that crippled him as an artist and performer.

The album opens with “Introduction,” one of three instrumentals that are scattered across the record’s duration. Joe Boyd is said to have argued against their inclusion in the recording sessions, but Nick Drake was single-mindedly adamant that they be included. “Introduction” is very thematically reminiscent of the tone of the first album, but then quickly segues into “Hazey Jane II,” which features — of all things — a complete horn section! This completely puzzled me upon first hearing it years ago, but as the album’s centerpiece “At the Chime of a City Clock” begins and you hear Ray Warleigh’s expressive tenor sax intro to the second verse, you soon realize that Drake wasn’t satisfied to be pigeonholed as strictly a folk artist. That jazzy ethos is perfectly appropriate for the more upbeat nature of the album. That’s followed by the most Beach Boy-ish of the album’s tunes, “One of These Things First,” which features the only instance of the two California session musicians together on any track. “Hazey Jane I” slows down the tone of the previous iteration to a crawl, featuring Drake’s remarkable fingerpicking on acoustic guitar. What would have been side one of the LP ends with the eponymous title track, which is a sunny instrumental that features a hippie-dippy but jazzily appropriate flute accompaniment from Lyn Dobson.

Side two opens with “Fly,” which is the most instrumentally spare tune of the entire album, and features John Cale’s viola and harpsichord, accompanied by Drake’s guitar and Dave Pegg’s bass. Drake is obviously trying to cope with his first album’s failure when he opines, “I’ve fallen far down/The first time around/Now I just sit on the ground in your way.” Dave Pegg’s bass vamp and Ray Warleigh’s alto sax turn shifts the musical course back to that jazz thing with “Poor Boy,” where Drake literally lays out his present condition: “Oh poor boy/So worried for his life/Oh poor boy/So keen to take a wife/Oh poor boy/So sorry for himself/Oh poor boy/So worried for his health.” This is also the only song on any Drake album to feature background vocalists, here showcasing the excellent work of Doris Troy — you might remember her from her Sixties hit “Just One Look.”

Following is one of Nick Drake’s most well known songs, “Northern Sky,” an atmospheric piece that has appeared in several movie and TV soundtracks, and was originally slated to be the lead single from Bryter Layter. Island Records decided against a single, further hindering the album’s chances for success. In 1985, the group the Dream Academy released their big hit “Life in a Northern Town,” which was credited in the album’s liner notes as being influenced by a Nick Drake song. In a BBC interview at the time, Dream Academy singer Nick Laird-Clowes further expounded on the Nick Drake connection with their music. The BBC was flooded with requests for Nick Drake’s song “Northern Sky,” which was really strange for BBC programmers, who essentially had no knowledge of Nick Drake and his music. So, while the Volkswagen “Pink Moon” commercial (see my article in Issue 162) might have been responsible for the subsequent worldwide awareness of Nick Drake, the Dream Academy’s 1985 song really launched the initial spark of modern interest.

The 24-bit/96 kHz FLACs for Bryter Layter aren’t too dissimilar in character to those of Five Leaves Left, and the sound quality is superb throughout. That said, producer Joe Boyd has made no efforts to hide the fact that the album was heavily multi-tracked – Nick Drake was already approaching the point where his studio interaction with the other musicians was beginning to suffer from his advancing schizophrenia. The resulting record has a slightly elevated level of tape hiss compared to the excellent-sounding debut album. That said, the 24/96 digital files still sound significantly better than either the CD copies or LPs from my personal library.

Bryter Layter is such a radical departure from the debut album; I can’t help but wonder what might have been had Nick Drake’s mental condition been such that he was able to effectively tour and support the record. While much more uplifting in nature than the previous album, hearing it compounds the sense of mystery that totally surrounds Nick Drake, the artist. After the album’s critical and commercial failure, Nick Drake retreated to Island Records head Chris Blackwell’s Spanish villa for a sabbatical to prepare for his life’s next chapter. Bryter Layter isn’t quite the sonic treat that Five Leaves Left was (and is!), but still comes very highly recommended.

Island Records (Universal Music), CD/LP/download from HDtracks (24/96) – Available for streaming on Qobuz, Tidal, Amazon, Pandora, Deezer, Apple Music, Spotify, YouTube

Nick Drake – Pink Moon

Prior to the failure of Bryter Layter, Nick Drake had already confided to Joe Boyd that he’d been working on new songs, and wanted to take a more stripped down approach on the next album, possibly using John Wood, Sound Techniques’ engineer, as the producer. Boyd expressed his disapproval, but knew that he probably wouldn’t even be there for the sessions, as he had already decided to take a new career opportunity and soon relocated to Los Angeles. When Drake did return to Sound Techniques in late October, 1971 with a new batch of songs in tow, he was then told that Joe Boyd had returned to the United States. It’s said that Nick Drake was crushed by Boyd’s decision to leave the UK, especially since Drake had already informed Boyd of his future plans. Boyd was, after all, Drake’s friend and confidant, and the closest thing he had to any kind of a “support group” in his very short life.

Drake arrived at the studio the morning of October 30, and he and John Wood began recording what would become Pink Moon. The sessions continued on the following day, and no studio musicians were required for any of the songs recorded, which only featured Drake’s guitar and vocals, although Drake added a brief piano part that was overdubbed onto the title track. The total running time of the album was under 30 minutes. When Nick Drake left with the finished tapes, it was the last time he would ever set foot in the studio where his entire catalog of albums had been recorded. Some days later, he arrived unannounced at the Island Records offices in London and was sitting in the lobby when Island press officer David Sandison returned from lunch and happened to notice him sitting there with what appeared to be a 15-inch master tape case. Sandison invited Drake up to his office, where he sat in silence for about 30 minutes, then announced that “perhaps he should be going.” About an hour or so later, the receptionist called up to Sandison’s office, telling him that someone had left a tape at the desk. He went downstairs and saw that the box was marked “NICK DRAKE: PINK MOON.” He then took it to the studio and had them run a safety copy from the master. The following day, he happened to mention to Chris Blackwell that Drake had dropped off the tape, and Blackwell then had his first listen. No one with Island Records had had any awareness that Drake was delivering his new album.

Despite its spare and stark nature, Chris Blackwell was extremely taken by the album, and contracted photographer Keith Morris to take new photos of Drake for the album cover. However, Morris was shocked by Nick Drake’s rapidly deteriorating appearance and constantly blank expression, and none of the photos were deemed appropriate for the album cover. The eventual album art was done by Michael Trevithick, who was a friend of Drake’s sister, Gabrielle, who saw to it that Drake approved of the artwork. Pink Moon streeted on February 25, 1972, and Chris Blackwell took out full-page ads in UK music magazines promoting the album. This was a significantly higher level of promotion than the previous albums had received, but the record’s critical reception was still chilly at best. No singles were released from the album, and with Drake’s refusal to tour or do interviews, it soon suffered the same commercial fate of its predecessors. Joe Boyd has stated that upon first hearing the album, he absolutely hated it, and felt that releasing it was tantamount to commercial suicide for Drake’s career.

The album opens with the eponymous title track, made famous by that 1999 Volkswagen Cabrio commercial. Of course, once the record suddenly reached a massive level of popularity as a result, the usual complaints came from the public regarding the use of popular music in advertisements. But the Volkswagen commercial was actually seen in retrospect as a watershed moment in advertising, where the ad was so well-done and aesthetically pleasing, and the music so perfectly integrated, that many popular artists then reassessed their views on allowing their music to be used to sell products.

Despite its brevity, the album features some really good songs, and due to the pared-down nature of the production, showcases Nick Drake’s fingerpicking guitar stylings to superb effect. A clear example is the song “Road,” which features some of Drake’s finest guitar work on any of his albums. I’ve hit the replay button countless times re-listening to this track, which is flat-out amazing! The song “From the Morning” is also among the very best and sunniest Drake ever wrote, and the passage “And now we rise/And we are everywhere” is engraved on the rear of Drake’s tombstone. With Pink Moon being the album that essentially brought Nick Drake to the attention of the wider world, it’s the one most people are most familiar with, and doesn’t need a blow-by-blow rundown on each song here.

If I have a complaint about the 24/96 digital remasters of Nick Drake’s three catalog albums, it’s with Pink Moon. It has a loudness level that’s about double that of the others; it’s not that it’s overly compressed, but it’s so very loud that I have to reduce the volume level of my amplifier to prevent it from distorting. I don’t hear this level discrepancy with the Universal 2013 LPs. I almost believe that this particular transfer was perhaps remastered at a later date by someone who subscribed to the loudness wars that started in the 2000s. The album essentially sounds fine once you’ve reduced the volume level, but why was this increased level even necessary in the first place? Pink Moon was probably tinkered with because it’s far and away the biggest seller of Drake’s catalog.

After Pink Moon crashed and burned after its initial release, Nick Drake retreated to the comfort and care of his family’s countryside estate, Far Leys, where he became even more withdrawn from society. Within two years, he was dead from an accidental overdose of prescription antidepressants. Yet he did eventually rise, and now he is everywhere.

Island Records (Universal Music), CD/LP/download from HDtracks (24/96) – Available for streaming on Qobuz, Tidal, Amazon, Pandora, Deezer, Apple Music, Spotify, YouTube

Conclusion

The 24-bit/96 kHz digital download files for the three Nick Drake catalog albums are, in my book, a vast improvement over the standard CD releases that preceded them. I still feel the remastered LPs – warts and all, and which may or may not have been sourced from those same digital files – are the slightest bit more sonically pleasing than their digital counterparts. The digital files aren’t perfect (Pink Moon is the main object of my scorn), but they’re probably about as close to perfection as we’re likely to encounter in our lifetimes.

Joe Boyd talks often in interviews about his experiences with Nick Drake, and you can’t help but believe that he views his involvement as both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, he was instrumental in the development and recording of a troubled, but singular artist beyond compare – there has never been, or never will be another talent the likes of Nick Drake. That said, Boyd has constantly been bombarded over the last couple of decades – essentially, since the Volkswagen commercial that featured “Pink Moon” hit the airwaves – with demo tapes from countless wannabes with odd guitar tunings and breathy vocals, who insist to Joe Boyd that “they’re as good as Nick Drake, aren’t they?” So far, “no” is the only answer he’s ever been able to come up with.

Header image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

0 comments