This article is part of a series of excerpts from The Audiophile's Guide, a 10-volume set that offers guidance and knowledge about all aspects of audio reproduction and system setup. Previous installments in this series on room treatment appeared in Issue 220, Issue 219, and Issue 218.

Optimizing the Listening Room: The Measurement Process

Before we start lugging speakers around the room, it’s time for some basic acoustic detective work. The fascinating part about room acoustics is that every space tells a story – we just need the right tools to hear it. And here’s the good news: those tools are probably sitting in your pocket right now.

Your smartphone, believe it or not, can be a surprisingly effective measuring device. While professional acousticians might raise their eyebrows at using a phone as a measurement tool, today’s smartphone microphones and apps are more than adequate for our needs. We’re not trying to certify a recording studio; we’re just looking for relative measurements to map out our room’s acoustic personality.

Several excellent sound pressure level (SPL) meter apps are available, many of them free or at minimal cost. For iPhone users, I’ve had good results with AudioTools, Sound‐Meter X, and the aptly named SPL Meter. Android users might want to try Sound Meter, SPL Meter, or Decibel X. While these apps might not match the absolute accuracy of a $2,000 professional measurement rig, they’re remarkably good at showing relative differences in sound pressure levels across a room, which is exactly what we need.

Our goal here is to create a basic acoustic map of our room before we bring in any speakers. Think of it as getting to know the space’s acoustic fingerprint. We want to understand how sound behaves in different parts of the room, particularly in the areas where we’ve marked for our speakers and listening position. First, we need a consistent sound source. While a smartphone’s tiny speaker might work in a pinch, this is really a job best handled by a proper speaker – even a small one will do better than your phone. A decent portable Bluetooth speaker like a JBL or Sonos can work well here, but ideally you’ll want to temporarily position one of your main speakers at the marked location. If you’re reading this before moving your main system in, consider bringing in just one speaker for these measurements. The goal is to have a sound source that can play a 1 kHz test tone cleanly and loudly enough to get reliable readings.

If you’re using a Bluetooth speaker, place it on a stand or chair to get it up to approximately the height where your main speaker’s tweeter will be, usually around 36 to 40 inches from the floor. Using a stand helps eliminate reflections from the floor that might skew our measurements. Set the volume to produce around 75–80 dB at one meter – loud enough to be well above the room’s background noise, but not so loud that you’re disturbing the neighbors or creating excessive reflections.

Play a simple 1 kHz test tone (easily found on YouTube or audio test sites). I prefer using dedicated test tone tracks from reputable sources like Dr. Chesky’s Ultimate Headphone Demonstration Disc, the Stereophile Test CD, or our own Octave Records’ The Stereo, but good quality online sources can work too. The key is consistency; once you set your volume, don’t adjust it during the measurement process.

Then, using a phone with your chosen SPL meter app, start taking measurements. Keep the measuring device at a consistent height and distance from your body. Walk slowly around the room, paying special attention to the areas you’ve marked for your listening position and the other speaker location. Take readings about every three feet, jotting down the numbers on a rough sketch of your room. Pay particular attention to corners and wall intersections – these are often problematic areas acoustically.

What we’re looking for are significant variations in sound pressure levels. If you notice differences of more than 3 dB between nearby points, make note of these; they’re telling us something important about how sound waves are interacting in your room. Areas where the sound pressure suddenly drops off might indicate cancellation points, while spots with higher readings might show us where sound waves are rein‐ forcing each other. Don’t worry if this seems a bit technical; we’re not trying to become acoustic engineers. What we’re doing is creating a basic “heat map” of our room’s acoustic behavior. This information will prove invaluable when we start fine-tuning our speaker positions, and it might even suggest areas where we’ll want to add acoustic treatment later.

Remember, we’re not looking for perfect uniformity – no room has that. What we’re after is an understanding of our room’s acoustic patterns so we can work with them rather than against them. Think of it like getting to know the currents in a river before you start swimming; it’s always better to work with the !ow than against it. In the next section, we’ll interpret these measurements and use them to refine our initial speaker positions. But for now, take your time with this mapping process. The more thorough you are at this stage, the easier our next steps will be.

A quick tip: keep your measuring phone at a consistent height – about ear level when seated is ideal. And try to maintain the same distance from your body while taking measurements; your presence can affect the readings more than you might think. I like to hold the phone at arm’s length to minimize this effect.

Mapping the Bass Landscape

Now comes one of the most critical aspects of room acoustics, understanding how bass frequencies behave in your space. Bass waves are like the foundation of a house: get them right, and everything else tends to fall into place. Get them wrong, and no amount of tweaking elsewhere will fix your sound.

Let’s start with a simple test tone sweep. For this test, we’re going to need a subwoofer, even if it means borrowing one from a friend. Your smartphone’s speakers or even most bookshelf speakers won’t produce the kind of clean, powerful bass frequencies we need for this test. Don’t worry too much about the quality of the sub; even a modest home theater subwoofer will work !ne for our purposes. Place it temporarily in one of the corners of the room where you won’t be putting your main speakers – we’re using it as a test instrument, not for its final position.

Using the same smartphone setup as before, this time play a series of low-frequency test tones through the subwoofer. Start at around 125 Hz, and work your way down to 40 Hz in roughly 10 Hz steps. You can find these tones online or through various audio test apps. Most subwoofers will have a volume control; set it so the 80 Hz tone is producing about 85 dB on your SPL meter app when measured from the center of the room. This level is loud enough to energize the room but not so loud that it will disturb the neighbors or mask subtle acoustic effects. What we’re looking for here is quite different from our earlier measurements.

A quick note: some of you might be tempted to skip the subwoofer step and use your main speakers, but I strongly advise against this. Most speakers, even floor-standers, struggle to produce consistent, clean bass below 50 Hz. Plus, using a subwoofer allows us to isolate the low frequencies we’re interested in measuring without the complications of mid and high frequencies muddying our results. Think of it as using a magnifying glass to examine just the bass region of your room.

As you play each tone, walk slowly around the room, paying particular attention to the corners and walls. You’ll notice something fascinating: the bass energy will seem to collect in certain spots while practically disappearing in others. These are your room’s standing waves at work. Make note of any locations where the bass seems particularly strong or weak. These nodes and antinodes, as we call them, can vary dramatically with frequency, which is why we test multiple frequencies.

But here’s where we add another tool to our arsenal – your hands. I’ve spent decades teaching audiophiles that their hands can be remarkably sensitive measurement devices. Place your palms flat against the walls while playing these bass tones. You’re looking for areas where the wall seems to vibrate sympathetically with certain frequencies. Some sections of wall might feel like they’re practically buzzing, while others remain relatively inert. These vibrating sections are effectively acting like passive bass radiators, not unlike the passive radiators some speaker manufacturers use in their designs. However, in our case, these vibrating wall sections are usually detrimental to good sound. They’re absorbing energy that should be reaching your ears, and often releasing it at slightly delayed times, muddying the bass response.

Pay special attention to large flat surfaces between wall studs. These areas are particularly prone to becoming unintended bass resonators. I’ve found that gently tapping these sections with your knuckles (like knocking on a door) can quickly reveal problem areas. If you hear a hollow, drum-like sound, you’ve found a spot that might need attention.

In areas where you find particularly resonant wall sections, consider where you might place furniture or bookshelves. A well-placed bookshelf, filled with books of varying sizes, can act as an excellent diffuser and help control these wall resonances. If you’re dealing with a particularly problematic wall section, you might want to consider some strategic reinforcement – anything from additional wall studs (if you’re willing to open up the wall) to mass-loaded vinyl barriers attached to the surface.

Remember those bass nodes and antinodes we mapped out? They’re going to be crucial when we fine-tune our speaker and listening positions. Often, moving your listening position just a foot or two can make the difference between boomy, overwhelming bass and clean, articulate low frequencies. In my experience, most rooms have at least one or two spots where bass tends to collect excessively, usually in corners. While we can’t eliminate these hot spots entirely, understanding where they are helps us make informed decisions about speaker placement and room treatment. You might find that one of your preliminary speaker positions falls right in a bass null, where low frequencies seem to disappear. That’s valuable information, suggesting we might need to adjust our layout.

This hand-on-wall technique might seem primitive compared to sophisticated measurement tools, but I’ve found it invaluable over the years. It gives you a tactile understanding of how your room is behaving that numbers alone can’t provide. I’ve seen plenty of expensive rooms with state-of-the-art acoustic treatment still suffer from basic wall resonance issues that could have been identified with this simple technique. What we’re building here is a comprehensive understanding of your room’s bass behavior, both in terms of standing waves in the air and mechanical resonances in the walls. This knowledge will prove invaluable as we move forward with speaker placement and eventual acoustic treatment decisions.

Points of first reflection.

Now that we’ve created our acoustic map and have a good sense of our room’s personality, it’s time to tackle one of the most critical aspects of room setup: identifying the points of first reflection. These points can make or break your stereo imaging and soundstage depth, and finding them is actually quite simple, though you might feel a bit silly doing it.

Let me introduce you to what we call the “mirror trick.” It’s been around since the early days of stereo, and despite all our modern measurement tools, it remains one of the most effective techniques in our acoustic toolbox. You’ll need a small mirror (a hand mirror works perfectly) and either a friend to help or a good pair of knee pads (trust me on this one).

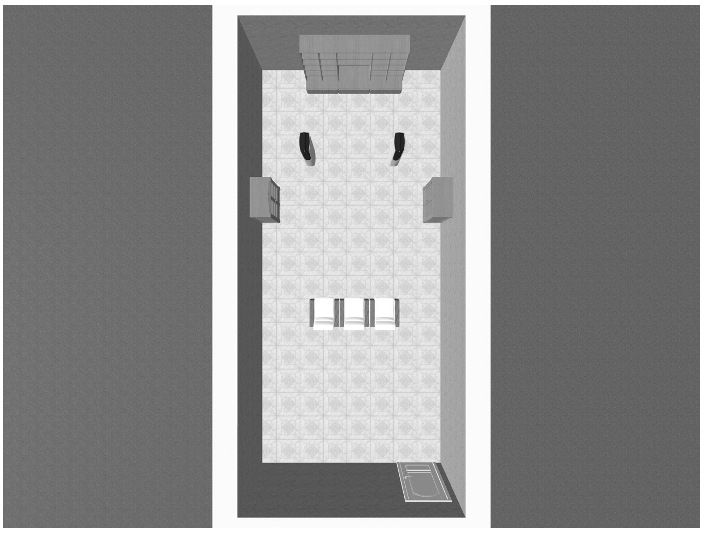

The Point of First Reflection

Have your friend slide the mirror slowly along the side wall, keeping it flat against the wall at the approximate height of your speakers’ tweeters. You sit in your marked listening position and watch the wall. At some point, you’ll see the reflection of your left speaker appear in the mirror. Bingo! Mark this spot with your blue tape – this is your first reflection point for the left speaker on the right wall. Do the same for the other speaker on the opposite wall. But we’re not done yet. You’ll want to repeat this process on the floor (this is where those knee pads come in handy if you’re working alone). And don’t forget to check the front wall behind the speakers for reflections that might bounce back to your listening position.

Why are these points so important? Think of them as acoustic mirrors bouncing sound directly to your ears, arriving just milliseconds after the direct sound from your speakers. These reflected sounds can either enhance or destroy the stereo image your speakers are trying to create. When the reflected sound arrives within about 20 milliseconds of the direct sound, your brain processes it as part of the original signal. Any later, and you start to perceive it as a distinct echo.

Here’s an interesting historical note: This understanding of first re!ections’ importance emerged from research done in the late 1960s by Dr. Helmut Haas, expanding on earlier work about the precedence effect. The high-end audio community, particularly through the writings of Roy Allison and later Peter Walker of Quad, began incorporating these findings into room setup techniques in the 1970s.

You might be surprised to find that these reflection points aren’t exactly where you expected them to be. That’s perfectly normal. Room geometry can create some unexpected paths for sound to travel. I’ve set up systems in hundreds of rooms over the years, and these reflection points still occasionally surprise me with their locations. For now, just mark these points; we’ll address treatment options later. What’s important is that we’ve identified them. Think of these points as acoustic hot spots that we’ll need to manage. They’re not necessarily bad – in fact, some designers argue that controlled first reflections can enhance the listening experience. But knowing where they are gives us power over how they affect our sound.

Diffuse the Situation

Now that we’ve identified those critical first reflection points, it’s time to do something about them. In my new listening room at PS Audio, I’ve chosen to use eight-foot-tall wooden diffusers at these points, and there’s a good reason for this choice. While absorption panels are more commonly recommended (and can work well), I’ve found that properly designed diffusers can maintain the room’s sense of life and space while controlling potentially problematic reflections.

Bookcases make great diffusers.

But not everyone wants their living room to look like a recording studio. One of the most aesthetically pleasing and effective solutions I’ve encountered over the years is the strategic placement of bookcases. A well-filled bookcase can be an amazingly effective diffuser, and there’s solid acoustic science behind why this works. Books of varying sizes, arranged on shelves, create an irregular surface that breaks up sound waves in much the same way as purpose-built diffusers. The different depths, heights, and densities of books create a naturally random pattern that scatters sound energy rather than reflecting it coherently. Plus, the spaces between and behind the books act as mini-absorbers, providing a nice balance of diffusion and absorption.

I’ve seen some beautiful listening rooms where floor-to-ceiling bookcases line the side walls at the reflection points. The key is to fill them somewhat randomly – don’t organize your books by size or create too uniform a pattern. Nature abhors straight lines, and so does good acoustics. Mix up hardcovers and paperbacks, add some decorative objects of different materials and shapes, perhaps even leave some spaces partially open. The more random the arrangement, the better the diffusion.

Behind the speakers, bookcases can be particularly effective. Not only do they help control those problematic back-wall re!ections, but they can also create an attractive focal point for the room. I’ve seen setups where a central equipment cabinet is flanked by bookcases, creating both an acoustic treatment and a natural entertainment center. The beauty of using bookcases is that they serve multiple purposes: they’re functional storage, they add visual warmth to the room, and they provide excellent acoustic treatment. Your significant other might be more amenable to bookcases than black acoustic panels, and your books finally have a purpose beyond collecting dust.

If you’re considering this approach, aim for shelves that are at least 12 inches deep – this gives you enough space for larger books and creates more effective diffusion. Avoid glass doors on the bookcases; you want the sound waves to interact directly with the books and shelves. And don’t worry too much about perfectly symmetrical arrangements – some randomness in the book placement actually helps with diffusion. Remember, whether you’re using purpose-built diffusers or bookcases, the goal is the same: to create a lively but controlled acoustic environment that enhances rather than detracts from your listening experience.

Think of diffusers as acoustic prisms. Instead of absorbing sound energy or reflecting it like a mirror, they scatter it in multiple directions, breaking up the coherent reflected wave that could interfere with our stereo image. This scattering effect helps maintain the room’s natural ambiance while preventing the focused reflections that can smear imaging and detail. The height of these diffusers is intentional. By extending them well above and below the speaker and listening heights, we’re managing reflections across a broader range of listening positions. You might not always sit perfectly still in your sweet spot, and these tall diffusers ensure good performance even as you move around a bit.

But let’s talk about that front wall, i.e. the one behind your speakers. This is where I typically add more diffusers, and there’s some interesting acoustical science behind this decision. When sound waves emerge from your speakers, they don’t just travel forward toward you; they also radiate backward. These back waves hit the front wall and can reflect back into the room, arriving at your ears significantly later than the direct sound. This delayed energy can blur detail and compress the sense of depth in your soundstage. By placing diffusers behind the speakers, we’re not trying to eliminate these reflections entirely (that’s what makes some heavily damped rooms sound dead and uninvolving). Instead, we’re scattering these reflections in a way that creates a more natural sense of space. It’s similar to how concert halls use diffusive surfaces to create a sense of envelopment without destroying clarity.

Diffusers or another bookshelf front wall.

I learned the importance of front wall treatment years ago when setting up systems in dozens of different rooms. Rooms with bare front walls often produced a somewhat flat, two-dimensional sound stage. Add proper diffusion behind the speakers, and suddenly the sound stage could extend well behind the speaker plane, creating that “looking through a window into the performance” effect that we all chase. The key is balance. Too much diffusion can make the room sound artificial or confused, while too little leaves us with those problematic focused reflections. In my room, I’ve found that covering about 40 percent of the front wall with diffusers provides the right balance between control and natural room sound.

As you position your diffusers, remember that they don’t need to be perfectly symmetrical (though the ones at the first re!ection points should be). The goal behind the speakers is controlled randomness, much like what you’d find in a well-designed concert hall. Some audiophiles even stagger their front wall diffusers at different distances from the wall to create additional randomization of reflections.

A common question I hear is, “Why treat the room before the speakers arrive?” It’s a fair question, but there’s real wisdom in tackling acoustics while the room is empty. Think of it as establishing the room’s basic acoustic personality before introducing your audio system into the equation. One of the simplest and most revealing tests you can do right now is the voice test. Stand in your marked listening position and speak in a normal conversational tone. Your voice should sound natural and alive, similar to how it sounds when you’re speaking outdoors or in a well-designed living room. If you hear a metallic ring or hollow coloration to your voice, that’s the room adding its own unwanted signature to the sound. If your voice sounds overly dead or muffled, we’ve probably gone too far with absorption. The goal is a lively but controlled acoustic environment.

This is also the perfect time to check for slap echo, that distinctive ping-pong effect you hear when sound bounces repeatedly between parallel surfaces. Do a sharp hand clap (or pop a balloon if you want to be more scientific about it) and listen carefully to what follows. In an untreated room, you’ll often hear a rapid series of distinct echoes – that’s slap echo, and it’s one of the most common enemies of good sound. It’s particularly problematic where walls meet each other or where walls meet the ceiling. These intersections act like acoustic mirrors, creating strong reflections that can bounce back and forth many times before dying away. This is why you’ll often see studios and listening rooms with some form of treatment in these areas. Even something as simple as crown molding can help break up these reflections, though more substantial treatment is often needed.

Corner bass traps like ASC Tube Traps.

For corner treatments, I’ve found that a combination of absorption and diffusion works best. The corners of rooms are notorious bass traps, places where low-frequency energy tends to collect and reinforce itself. Simple triangular bass traps in corners can work wonders, but don’t forget the corners where walls meet the ceiling. These are often overlooked but can be just as problematic.

An interesting solution I’ve used for ceiling/wall intersections is to install wooden diffuser strips at an angle, creating a kind of acoustic crown molding. This serves both an aesthetic and acoustic purpose, helping to scatter those problematic reflections while maintaining the room’s visual appeal. If you’re going with traditional crown molding, consider using larger profiles – the more complex the shape, the better it tends to work as a diffuser. The beauty of doing this work now, before your speakers arrive, is that you can more easily hear the room’s native acoustic character without the complexities of speaker interaction. It’s like having a conversation with the room itself, understanding its quirks and characteristics before adding the additional variables that speakers introduce.

Take your time with this process. Walk around the room, clap, talk, listen. You’re looking for a space that sounds neutral and natural, where your voice maintains its natural timbre and handclaps decay quickly and evenly without any obvious flutter or ringing. When you achieve this, you’ve created an excellent foundation for your speaker setup. Remember, you can always fine-tune things once the speakers are in place, but getting the room’s basic acoustic signature right at this stage will make that final optimization much easier. Think of it as preparing a clean canvas before starting to paint – the better your foundation, the easier it will be to create your acoustic masterpiece.