In the consumer packaged goods biz, it’s common practice for manufacturers to reposition brands as “new and improved.” We’ve seen brands like Tide, Jell-O and Bounty do this time and again. (The irony is “new and improved” is an oxymoron, but don’t tell the suits over at Procter & Gamble.) It isn’t too surprising that similar marketing tactics are successfully being deployed in the music biz. The reissuing of classic rock LPs is sort of a Marketing 101 spin on “new and improved,” though done with language that’s a bit less crass.

We’ve seen lots of classic rock 20-, 30-, and 40-year anniversary reissues, only to be surpassed more recently by a few 50-year anniversary releases. Since 2009, Steven Wilson (producer, solo artist, Porcupine Tree) has received the most notoriety from his work remixing classic rock LPs, and deservedly so. Wilson’s remixed albums from King Crimson, Jethro Tull, Yes, ELP, Chicago, Roxy Music, Tears For Fears, and Gentle Giant, all generally available in streaming and physical formats.

In interviews describing his approach on remixing, Steven Wilson said, “I’m working from the very raw sources upward. My process is to load up the multitrack analog tapes alongside with the original stereo mix (side-by-side). I’m literally listening in five-second chunks, comparing the original mix and my new mix. With Blu-ray or 5.1 surround sound, I’m creating a more immersive 3-dimensional version. It’s like cleaning the Sistine Chapel, taking off layers of grime.” Wilson relies on isolated tracks that contain no reverb, EQ or compression.

Wilson also noted having “spirited” conversations with Robert Fripp (King Crimson), Ian Anderson (Jethro Tull) and Greg Lake (Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Crimson) about remaining true to their original creations. The guys evidently wanted to “fix” a few things. Wilson told them in no uncertain terms the goal was to clean up, not reinvent, their original recordings. “Your fans would accept nothing less,” he said.

I’ve questioned the value proposition on some reissues, particularly when there’s limited upside in material and/or audio quality. Remember, demos are considered demos for a reason, though it is interesting to hear the evolution of a track or an LP. Is a reissue today primarily about accessing technology that wasn’t available at the time of an album’s creation? Are there legitimate opportunities for sound enrichment? Or is most of this a head fake, and more about the Benjamins?

The answers to these questions are nuanced and varied. In assessing the value proposition on a reissue, I generally take into consideration three things:

1) What is the quality and the type of source material available to a producer/engineer?

2) What are their goals and objectives?

3) How respectful are they to an artist’s original creation?

By far the most critical variable is the source material. If a remix relies on the original analog multitrack tapes – that are in good condition, with lots of isolation between tracks – then that will pique my interest. If a CD digital master is used to produce a 180-gram vinyl reissue, well, for me that’s a sonic head fake with considerably less value.

The folks spearheading these projects carefully characterize their work as “reimagining” rather than “improving” an LP, demonstrating linguistic creativity and a skill for controversy avoidance. But let’s face it, when you’re talking about the third or fourth time a recording has been reissued, in a variety of formats, its appeal is likely more for fanatics than everyday music fans.

In theory, you can see how modern-day post-production using cleaner, isolated tracks can potentially be beneficial. In the 1960s, when state-of-the art recording technology was limited to 4- or 8-track analog, engineers frequently had to “bounce” tracks – combine two or more tracks to make room for additional tracks – which lead to sound degradation from multi-generational mixing.

King Crimson’s In the Court of the Crimson King (1969), one of my all-time favorite LPs, was originally an 8-track recording. The album’s production was a bit experimental with lots of layering with Mellotron, sound effects and other instruments added, leading to a number of “bounced” tracks. In the album’s original mix, drums, guitar and bass are essentially third-generation copies, creating some sound degradation, hiss and harmonic distortion.

King Crimson, In the Court of the Crimson King, front and back covers of the expanded 2019 CD/Blu-ray edition.

Wilson remixed both the 40th and 50th anniversary reissues of In the Court of the Crimson King. Said Wilson, “The 40th was one of my first classic album projects, so while I think that mix is pretty good, I was happy to revisit it with the benefit of 10 years’ experience. I think the new mix (the 50th) is a significant improvement and more faithful to the 1969 mix, done at 96/24 resolution.”

The sound on both reissues to me is quite stellar; though pardon my cynicism in asking if there’ll be a 60th Anniversary reissue? Does the law of diminishing returns apply with each successive release? Which brings us back to the Benjamins. There indeed is a market for this stuff among fanatics, but it’s likely not insatiable, especially if there’s only marginal gain with each consecutive reissue.

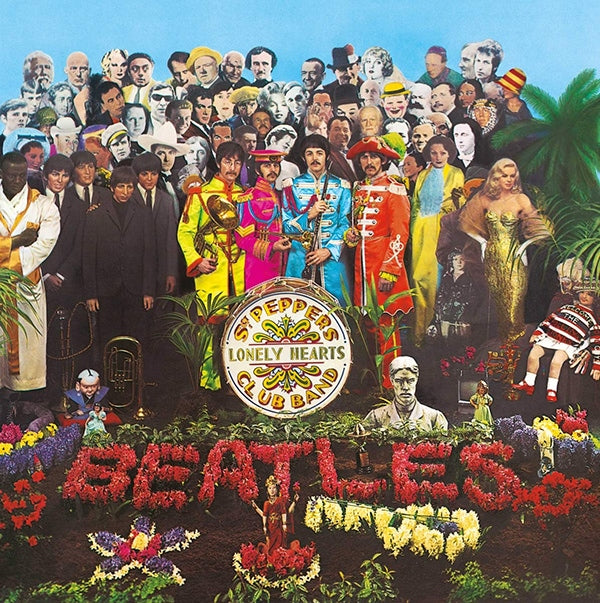

Giles Martin, son of legendary Beatles producer George Martin, was responsible for remixing the 50th anniversary releases of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), The Beatles (1968 – better known as the White Album) and Abbey Road (1969).

The earliest Beatles LPs were produced using a museum quality 2-track recorder, with 4-track introduced in ’63 with “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” Only in ’68 did the Beatles begin recording in 8-track, which utilized wider and higher-quality audiotape.

For most of the Beatles’ recording years, the primary listening devices for music enthusiasts were car radios and transistor radios, with an occasional living room console sprinkled in. The standard for the era, therefore, was to finish an LP in mono, not stereo. Producer George Martin spent three weeks on the mono mix of Sgt. Pepper, and three days on the stereo mix, indicating its far lesser importance.

With the Beatles 50th Anniversary reissues, Giles Martin had access to both first-generation analog tapes, and his father’s meticulous notes. As a result, there’s “purity” in the mix that wasn’t technologically available when these albums were originally produced. Giles was also doing double duty with these reissues, needing to remain true to both the Beatles’ and his father’s legacy. “You’re challenged by this weight of expectation,” he said, “but the joy is actually just finding how great Geoff Emerick’s (sound) engineering was, and how great my dad (George Martin) was as a producer.”

When you’ve listened to a favorite song or album for decades – presumably hundreds of times – a type of confirmation bias sets in, either consciously or unconsciously. When large or even modest changes are introduced, they can be confusing, hard to process and disruptive to listeners. There is dissonance, even when the familiarity and repetition of a well-known song or LP delivers a certain level of comfort.

The 50th Anniversary reissue of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s Déjà Vu (1970) on Rhino Records includes the album’s original tracks, plus thirty-eight unreleased demos, outtakes, and alternate takes, spread over four CDs and one LP. (The deluxe edition has five LPs, at an everyday low price of $249.98.) All LPs are produced on 180-gram vinyl remastered by Chris Bellman, relying on tapes from the original 1969 sessions recorded at the famed Wally Heider Studios. The original vinyl release was engineered by Bill Halverson and mastered by Al Brown. In between those two releases, Classic Records in 2005 released another Déjà Vu reissue on 200-gram vinyl remastered by Bernie Grundman.

So, if you’re keeping score at home, the original Déjà Vu LP (1970) was mastered by Al Brown, followed by a Bernie Grundman vinyl reissue and then another by Chris Bellman. The Bellman and Grundman vinyl masters were cut on the same lathe and cutter head, though the sound of the two releases is quite different. How’s that possible? During the mastering process, an engineer can easily play with the EQ – the amount of amplification at the low, medium and/or high ranges – and significantly affect an LP’s end-product sound.

With the 50th reissue, each CSNY band member had input on the selection of tracks, outtakes, demos, etc., but no input on the mastering process. It’s also been reported that Neil Young yanked some bonus material featuring his voice from the set.

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young Deja Vu 50th anniversary edition.

David Crosby, who sold off his ownership rights to the band’s catalog to music majordomo Irving Azoff, said this about the 50 Anniversary release of Déjà vu: “I’m happy about it, but I don’t have a dog in that fight, really. I sold (my rights to) the piece.” Which begs the question: if an artist sells off his or her rights, does a new rightsholder have an obligation to remain true to an original recording, or is anything and everything fair game? Are there creative, moral and/or ethical considerations that come with third-party ownership?

Interestingly, with CSN’s debut album, Crosby, Stills & Nash (1969), all three vocals were recorded on a single track, not individually, thereby minimizing some EQ options in mixing and mastering. According to Nash, a goal with the first record was to “take three voices and turn them into one,” done naturally and without electronic manipulation. That wasn’t the case with Déjà Vu, as each band member’s vocals were recorded separately; though the album’s entire production often has been described as “chaotic.”

Jimmy Page, keeper of the Led Zeppelin flame, had this to say about his band’s reissues: “I have to (get involved). I couldn’t suffer from anything but the best possible reissues. It’s all done from the original 1/4-inch tape. It’s all analog sources.” He further added that he was troubled by the detail and nuance lost with MP3 compression.

And then there’s the mastering process, which introduces even more variables and subjectivity. Mastering is done to complete and finish the mix to a specific format, whether it’s LP, CD, SACD, Blu-ray, 5.1 surround sound and so on. When you add another set of ears to the process – the mastering engineer’s – the end-product sound can change even further.

In sum, I think the sound on most recent classic LP reissues that I’ve listened to is quite good. There’s perceptibly more clarity. CSNY’s 50th Anniversary reissue of Déjà Vu seems to have been done with great care and consideration. The Beatles remixes are also good, but given the archaic technology available with the band’s early recordings (less so with Abbey Road), there was the potential for Giles to really “stretch out” in remixing and remastering, which, of course, would have opened the door to even greater scrutiny of his work. In my opinion, Giles struck a nice balance.

If the trend on anniversary reissues continues, and each subsequent release only delivers marginal gain in content and/or quality, then that’s a bit disconcerting and potentially exploitative of purchasers. Of course, some fanatics may view any and all releases, at a minimum, as collectibles.

So what are your thoughts on some of these reissues: real value or sonic head fake?

Addendum: A reissue of George Harrison’s classic triple-LP All Things Must Pass (1970) was released a week or so ago. This 50th anniversary project was overseen by Harrison’s son Dhani. The LP’s original production was spearheaded by producer Phil Spector, who incorporated his famed Wall of Sound approach to the recording. For quite some time, George evidently believed the original album was overproduced, with way too much reverb. Dhani Harrison approached the remixing of these LPs with that concern in mind, in addition to adding a slew of bonus material. In my opinion, this reissue is a classic example of overreach and too much reinterpretation. The remix is a radical departure from the original 1970 release. Far too much of Spector’s Wall of Sound is stripped away in the remix, while George’s vocals throughout are way too hot. The remix lacks the depth of the album’s original release. I found it immensely dissatisfying.