As a result of COVID-19, the Audio Engineering Society’s AES Show Spring 2021, appropriately named “Global Resonance,” was conducted online from Europe. This afforded me the rare opportunity to view a number of the presentations, which would have been otherwise impossible.

This show focused more on the academic side of audio technology than the previous New York-based AES Show Fall 2020. In Part One of Copper’s AES Show Spring 2021 coverage (Issue 139), I looked at presentations on binaural audio, audio mixing for residential television viewing environments, and an analysis of differences between Western and Chinese hip-hop music. Part Two (Issue 140) focused on psychoacoustics and studies on emotional responses to sounds. Part Three (Issue 141) covered the technology side of audio/video transmission, and the efforts to achieve greater realism in sampled orchestras. This final installment will focus on sound for interactive video games, and a tribute to the late Rupert Neve.

Audio in Games and Interactive Media

As mentioned in Part One, audio for games has reached a stage where it demands as much attention and expertise as is needed for feature films. This especially holds true for virtual reality (VR) games, where the demand for binaural and 3D sonic realism has even prompted a resurgence in the use of dummy head recording platforms.

Audio in Games and Interactive Media was collaboratively presented by gaming and VR technology research scholar Katja Rogers (host), game music composer Winifred Phillips (Assassin’s Creed, God of War, The Sims), journalist Sarah Fartuun Heinze (author of several pieces on the intersection of video, art, music, and interactivity), and sound designer and composer Mathilde Hoffmann (the Unreal series). They discussed both technical and aesthetic challenges in music and sound design that are unique to video games, VR, and interactive media.

Winifred Phillips explained that composing music for interactive vs. “linear” media has significant differences. Having a beginning, middle and end, with defined moments and timing as in linear media doesn’t exist the same way in interactive media, which constantly has to change. Games give the players control over the sonic (and visual) environment, so the music has to respond to the players’ choices. Music thus has to be composed in a modular way so that it can be disassembled and reassembled dynamically depending on the players’ reactions.

She also explained about the selection of musical genres for a game project as being a key consideration for a composer. The characters and their actions in the game often will dictate the themes in the music score. However, an awareness of the psychology of the gamers also needs to be factored in, so as to successfully meet the players’ expectations while simultaneously avoiding predictability. For example, action-filled games will tend to have more aggressive music, often with a heavy metal-style score to reflect the high-energy visual content.

Mathilde Hoffmann spoke enthusiastically about the creative process in sound design and for fantasy-based games in particular. In order to create a brand new sonic world, she enjoys finding sound sources, manipulating them, and making choices between acoustic and synthesized sounds. Due to the fast pace of games, signature sounds that have maximum impact have to be found quickly, as budgets often do not allow for a slow compilation of customized, nuanced sounds. Using the creation of sounds for monsters, for example, there have to be variations in movement, footsteps and vocal sounds, depending on the mood of the game and what the monster and the players are reacting to.

Sarah Fartuun Heinze compared the different types of interactivity between attending the theater vs. playing games, with musical theater coming closer to the same functions and emotional arcs as experienced in games. She noted the genre of game theater, a style of gaming that uses elements of theater, game aesthetics, live-action role players (“larp”) and offers a mashup of all of these elements.

Screenshot of Mathilde Hoffmann – Audio in Games and Interactive Media. Courtesy of AES.

Screenshot of Mathilde Hoffmann – Audio in Games and Interactive Media. Courtesy of AES.Hoffmann felt it was important not to let music and sound fall into predictable clichés, where the sounds almost dictate to the players what emotions they are supposed to experience, like a sitcom laugh track. Hyper-realism and subtlety work better, in her estimation, so that the sound design becomes almost transparent, and the player can fully immerse him or herself into the game world without feeling manipulated. In some cases, hearing the music and sound design of a game prior to seeing the game’s visuals can create an entirely different image in one’s mind.

She also explained how game designers use the Pavlovian familiarity response in their work. For example, high-pitched, repetitive sounds are recognized in many cultures as a warning signal, or at the very least, something that puts the listener on mental alert.

Phillips reminded the participants that communication within a game development team is crucial, because individual frames of reference can be so subjective. She insists that actual music references, rather than just verbal descriptions of music styles, be utilized whenever possible so that there is clarity in understanding, in order for all of the members of the development team to be on the same page. Case in point: Megadeth and Black Sabbath are both categorized as metal bands, but sound very different.

Getting consensus on acoustics and sounds within the development team is a must, and whatever helps the process, whether reference tracks, demo sounds and so on are all useful tools for game audio design engineers.

Phillips also pointed out that some players might spend hundreds or even thousands of hours with a game, at which point they will experience a great deal of exposure to the music and sounds. (That said, there is a trend among players to cut out the volume of the music during some games, especially shooter-based games, in order to more closely focus their concentration.) Therefore, one of the composer’s jobs is to build in enough variation so that each playing experience is both unique, yet familiar.

Along that same notion was a concern about how music can potentially reduce the immersion aspect of game playing, especially if the player dislikes the music genre used, or if it seems too divorced from reality, as in VR games. (Note: “immersion” in the gaming context refers to the player’s engagement in the virtual game world and not to immersive 3D sound per se.) However, since games are entertainment and a controlled, guided journey hyper-reality experience, the music is a necessary identity-enhancing aspect.

The discussion concluded with a thank you to VR games, which serve as a driver for cutting-edge audio research and development. Gaming audio has become a much bigger challenge, and immersive-sound technologies like spatialized audio and binaural audio have made resurgences.

Screenshot of Katja Rogers – Audio in Games and Interactive Media. Courtesy of AES.

Screenshot of Katja Rogers – Audio in Games and Interactive Media. Courtesy of AES.- Narrative fragmentation;

- Retention of a sense of freedom by players or audiences;

- Keeping a “less is more” approach to instruction in order to make it more intuitive.

Screenshot from Guiding Audiences With Sound: Techniques for Interactive Games and Video. Courtesy of AES.

Screenshot from Guiding Audiences With Sound: Techniques for Interactive Games and Video. Courtesy of AES.Harrison used Batman: Arkham Asylum as an example of an “open world” interactive game that suffers from narrative fragmentation. It has many plot layers and characters and is difficult for players who are unversed in all of the character and scenario details from the Batman canon to navigate to the different layers within the game without third-party guidance. The same problem occurs in immersive theater when there are too many narrative roads that can easily mislead audiences into different tangents, and thus miss key points and messages within the theater piece’s main theme.

At the same time, the sense of freedom and individual choice is a big appeal of interactive media. It is also crucial not to deluge gamers or audiences with voluminous instructions or heavy hand-holding, which ruin the whole exploratory experience of interactive media.

Sound design is a key tool for bridging these obstacles, as it can subliminally serve as an instructional guide. Designing sounds to trigger different listening modes, for example, will alter how gamers assimilate the content and their ability to make individual choices in the game’s interactive engagement.

Given the importance of sound and music design in the interactive experience, nothing can be accidental, and everything that can be heard should be deliberately chosen for its function in communicating information to gamers and audiences. Retaining sounds that do not contribute in this way can lead to erroneous conclusions by the gamer and audience, or worse, destroy the verisimilitude of the game or other medium in question.

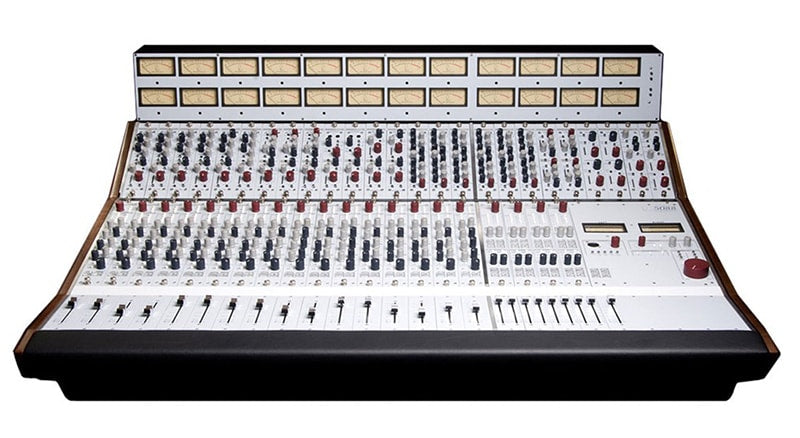

Audio can also be used as an interface by which, in the case of video games, a user can be informed of status (for example, in a game where one’s avatar is injured or dying, the quality of the sound can be altered, to simulate diminished capacity). It is also important to match the sounds of the real worlds and the virtual world of the game, in order to maintain the game’s sonic “reality.” As examples, these would include simulating the sound of open versus enclosed spaces (using delay and reverb as appropriate), footsteps on pavement as opposed to in a forest, and a host of other audio elements.

Maintaining a consistency of sound helps to serve as intuitive instruction, such as the “boing” sound for jumping used in Super Mario Bros. Warning sounds like sirens or beeps can signal to gamers that they are attempting actions that will not be usable within a game.

Semiotics within interactive games are sounds that take common sounds that are imbued with established meanings within Western culture, and are applied to the game’s virtual reality. For example, sounds like a “ding” are associated with something positive (this originated with pinball machines and later became used for text messages on phones). A musical interval of a rising fifth is interpreted as being “heroic”; for example, in John Williams’ Superman theme, while the more dissonant tritones, aka, “The Devil’s Interval,” are associated with evil, as used by Danny Elfman in the Batman theme and Hela’s theme by Mark Mothersbaugh in Thor: Ragnarok). The sliding down of a note by five half-steps or more connotes “failure,” often heard in cartoons.

Bass sounds are used to immerse the listener into the space and atmosphere of the created reality, while higher-frequency sounds give clues about the direction of movement, location, or proximity of other characters or objects.

Screenshot from Guiding Audiences With Sound: Techniques for Interactive Games and Video. Courtesy of AES.

Screenshot from Guiding Audiences With Sound: Techniques for Interactive Games and Video. Courtesy of AES.- Hiding “interesting” sounds, i.e. muffled voices or unique associated sounds, behind closed doors;

- Taking advantage of the natural human inclination to gravitate towards voices;

- Making “interesting” sounds move, rather than keeping them static.

Screenshot from Guiding Audiences With Sound: Techniques for Interactive Games and Video. Courtesy of AES.

Screenshot from Guiding Audiences With Sound: Techniques for Interactive Games and Video. Courtesy of AES.

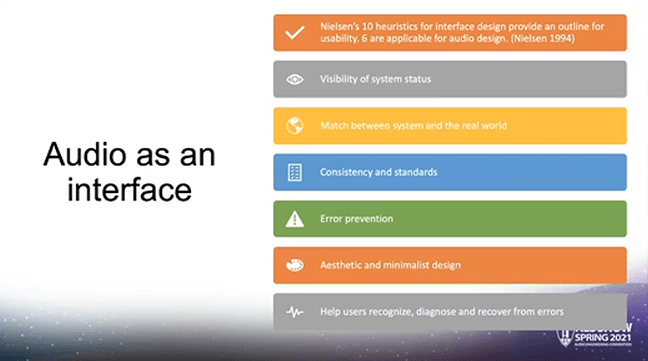

A Rupert Neve Retrospective: Sound Over Specs

The late Rupert Neve was an audio pioneer in microphone preamp, mixing console and compressor design. His “flying faders” automated consoles were responsible for much of the sound of contemporary music from the 1970s to the present, where top-flight recording studios like Nashville’s Blackbird Studio refuse to use anything else. Neve later founded Focusrite, which revolutionized the use of DAW (digital audio workstations) in home studios in much the same way. Neve passed away earlier this year in February, 2021. AES held a symposium tribute to Rupert Neve, “a name associated with the highest quality of audio,” as they put it, featuring commentary from George Massenburg (recording engineer, inventor and principal of George Massenburg Labs), Alex Case (moderator, associate professor at the University of Massachusetts Lowell), Steve Rosenthal (The Magic Shop recording studio), Darrell Thorp (nine-time Grammy winning engineer), Josh Thomas (Rupert Neve Designs, Amek), and Ronald Prent (Wisseloord Studio, The Netherlands).

Rupert Neve.

Rupert Neve.Steve Rosenthal recalled that there was a movement in the 1980s to actually get rid of consoles, and that compressors and other outboard signal-processing gear could be run independently in a signal chain without one. Having met Neve at an AES Show, Rosenthal became convinced of the folly of such a premise, and went on to use his Neve at The Magic Shop in New York’s Soho district, where David Bowie, Lou Reed, Blondie and others recorded iconic albums.

Josh Thomas had met Neve in 1991 while still working at console manufacturer Amek. Neve hired Thomas in 2005 after relocating to Texas to found Rupert Neve Designs. Neve was always excited about the “next” thing, and never looked back. For example, he was able to add an extra 10 dB of dynamic range into his consoles during his twilight years, and still listened to prototype designs at low volume levels for weeks to months on end for final tweaking.

Ronald Prent noted that when working with Rammstein, he was using an SSL console for recording and the band was unhappy after ten (10) days of using the console because their mixes “lacked power.” Prent then ran the signal directly through a chain of Neve 1073 mic preamps and Neve 2254 compressors, which then satisfied the band.

Darrell Thorp worked with the Foo Fighters on their latest record, using the original Neve 8028 used at Sound City Studios in Los Angeles that Dave Grohl had restored to spec. It turns out that EastWest Studios in Hollywood, California has a sister Neve 8028 console made during the same time frame. Thorp believes that Grohl’s Neve 8028 is grittier and edgier-sounding than EastWest’s model.

Screenshot from Rupert Neve Retrospective: Sound Over Spec, courtesy of AES.

Screenshot from Rupert Neve Retrospective: Sound Over Spec, courtesy of AES.Thorp feels that the Neve 1073 is a preamp that works for every genre of music and that its musicality is universally pleasing.

George Massenburg, who knew Neve starting in the 1970s, recalled how wowed he, Linda Ronstadt, and the members of Little Feat all were at first hearing the sound of a Neve console while making Ronstadt’s Heart Like a Wheel. In addition to always sounding great, Massenburg, credited as the creator and pioneer of parametric equalization, said that Neve console specs were always honest, unlike other manufacturers who overhyped specs on recall that would be +/- 4 dB off. Massenburg later worked with Neve on the recall mix system for Focusrite, making sure to keep the same level of technical exactitude.

All of the panelists concurred that Rupert Neve’s attention to listening was unparalleled. Even when test equipment measured two different units as the same, if Rupert heard a difference, they would eventually find the technical cause for the discrepancy. Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick was an even better listener and if Emerick could hear something, the Neve engineers would have to go back to find out what the cause was. In one case, after Emerick insisted he could hear a difference, a transformer that had a minor wiring discrepancy was found to be the ultimate culprit (generating noise at 53 kHz).

How fitting that the conclusion of our overview series on AES Show Spring 2021 brings us back to a standard of audio excellence upheld by AES and symbolized by an iconic designer like Rupert Neve!

Header image: Neve 5088 16-channel mixing console.