One of the popular mantras in audiophilia is “garbage in, garbage out.” This is meant to say a piece of equipment is only as good as what comes before it. Ivor Tiefenbrun, the founder of Linn Products, used to say that his Sondek LP12 record player sounded better played through a transistor radio than his competitors’ products played through a proper stereo system. In my first article for Copper, I mentioned my very first audio buddy Neil, whom I met in medical school and who was a Linn enthusiast. He was the one who told me about Ivor’s quote, and in fact, I just met up with him in Scotland earlier this month for the first time in 33 years. He is still playing his Linn Sondek, which remains in its original configuration, although he is contemplating getting the modern upgrades. He has also wisely kept all his LPs. A true lifelong Linnie!

What people sometimes forget is that the software (LP, CD, digital file) and the room play an important role in determining the sound quality, even more so than the hardware, though we do not often think of these as part of our audio system. Even Ivor’s turntable cannot make a poor recording sound good. Therefore, the recording engineer plays the most important role in how a recording sounds in your system, followed by the mastering engineer, and then the designers of your record player, amplifiers and loudspeakers. Of course, this is not always true, given my experience with some horrible-sounding loudspeakers (and their cost is irrelevant here) that can utterly ruin an otherwise excellent system. However, in my experience, the difference between competently-designed modern turntables and amplifiers (even those of modest cost) is less than the difference between well- and poorly-engineered recordings. In fact, higher-quality hardware often renders the faults of poor recordings even more obvious. Some record labels make consistently great-sounding recordings, such as Decca and Mercury during their golden years. The people who ran those labels recognized the importance of sound quality and hired the best engineers to make their recordings. This is why many of these recordings are still being reissued today, after 60-odd years, and are still being held as benchmarks against which modern recordings are compared.

Most audiophiles have probably heard of the names Kenneth Wilkinson (Decca) and Robert C. Fine (Mercury), who are justifiably celebrated as patron saints of recording engineers. Few would have heard of Marc Aubort, even though he is held in equally high esteem within professional audio circles Maybe the reason is because he founded his own company (Elite Recordings) in 1965 after spending nine years as chief engineer at Vanguard Records, and spent most of his career doing work on a per-project basis for smaller labels. He remained active until the 2000s, well into his 80s. He made many recordings for the classical labels Nonesuch and Vox/Turnabout. Unfortunately, the quality of the original LPs from these labels is often inconsistent, especially those made during the oil crisis of the 1970s when noisy recycled vinyl was used for these budget releases.

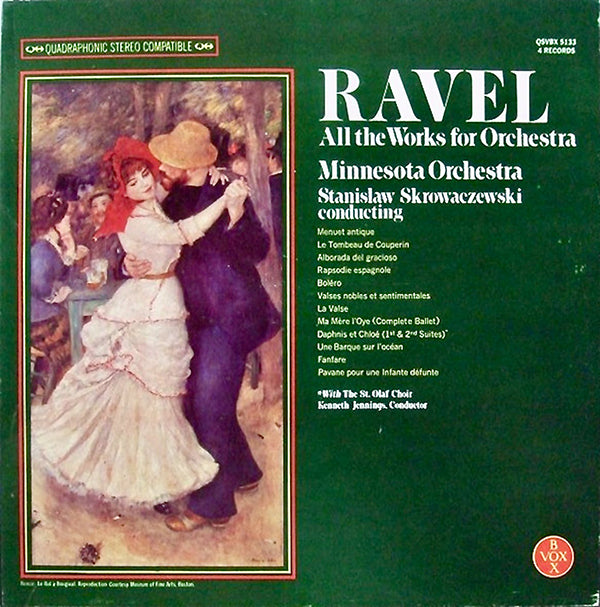

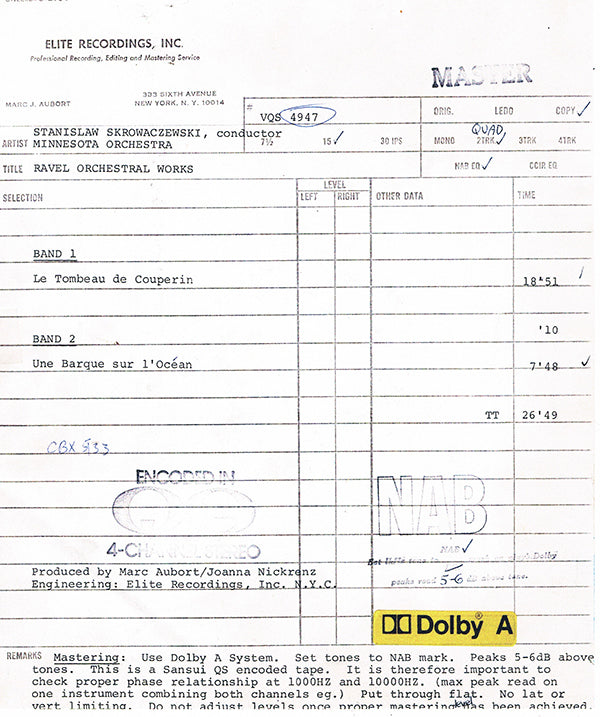

I was first introduced to his recordings when I came across an LP reissued by Analogue Productions in 1992 of Ravel compositions titled Works for Orchestra, with Stanislaw Skrowaczewski conducting the Minnesota Orchestra. It was one of AP’s earliest reissues, their seventh in fact, in collaboration with mastering engineer Doug Sax. I was blown away by how great the LP sounded. These recordings were made in 1974, shortly after the inauguration of the new Minnesota Symphony Hall, and released in the following year in a Vox box set of four LPs. One of the tape collectors I am friendly with bought some of the master tapes from Elite Recordings when Aubort retired, including this Ravel set. He agreed to make a copy of the whole set for me. The original recording was made in quadraphonic sound, and there are specific instructions on the tape boxes on how to master for stereo. Listening to the tapes was quite a revelation for me.

Ravel, Works for Orchestra, album cover.

Skrowaczewski was Polish but he spent his post-war years in Paris. He was first invited to the US by George Szell to conduct the Cleveland Orchestra, and occupied the post of music director at Minnesota (called the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra at the time) from 1960 until 1979, filling the shoes of Antal Dorati. He continued to conduct the orchestra for another 37 years as conductor laureate. The US had the best orchestras for French music outside of France during the post-war years, with Paul Paray, Charles Munch, Pierre Monteux and Skrowaczewski directing major American orchestras.

The set contains all of Ravel’s compositions for orchestra, and in my opinion, the most notable performance is the Bolero. Ravel indicated on the score that the piece is supposed to be performed over 17 minutes at a constant tempo. Many interpreters speed up at the end, that is, almost everyone except Skrowaczewski. The piece has a constant beat throughout, accompanying several phrases played by different instruments in turn, that are repeated over and over, with a gradual crescendo going from the quietest pianissimo at the beginning to the loudest fortissimo at the end. In recent years, some neuroscientists came to the conclusion that the repetitive nature of the composition (one of Ravel’s last) was a sign of Ravel’s impending dementia. Many conductors believe that the piece will be intolerably boring if played at the tempo indicated by Ravel. The composer himself was so irritated by the fast tempo of Toscanini’s performance with the New York Philharmonic that he refused to stand for the ovation at the end. When confronted by Ravel backstage, the conductor retorted that it was the only way the piece could be “saved.” The two men fell out over this incident and Toscanini subsequently refused to conduct the premiere of Ravel’s Piano Concerto for the Left Hand.

Bolero is one of Ravel’s most popular pieces, and many recordings exist, with most of them speeding up the tempo towards the end in order to add excitement. Those that adhere to Ravel’s tempo markings often sound ponderous and lacking in intensity. Skrowaczewski’s performance is none of these things. He allows a certain flexibility with the rhythm to avoid sounding mechanical, but maintains his grip on the tempo right until the end, choosing instead to build up the tension with the crescendo and the intensity of the playing. He adds color by subtly altering the tonality and dynamics of the solo instruments as the piece progresses. The ebb and flow of the musical line is lovingly shaped. The recording is brilliant at bringing out the tonality of the instruments and the subtle nuances of dynamic expression that makes the piece colorful instead of repetitive. It starts off as meditative, with an inexorable buildup of tension throughout its 17 minutes and 19 seconds that is released in one final climatic catharsis, all the while staying within the boundaries imposed by the composer. For me, this is the definitive interpretation of this piece.

Ravel, All the Works for Orchestra, quadraphonic LP box set album cover.

A published interview with Aubort has documented how his stereo recording technique changed over the years, which was very little. He employed the same microphones (Schoeps 221B, which employs the AC701 miniature tube) from almost the beginning right to the end of his career. He commonly used a stereo pair with omnidirectional capsules, placed at the front of the stage, sometimes supplemented by two additional flanking mics if the venue was large. It appears that he eschewed the use of spot mics. This avoids the problems associated with phase cancellation and makes preserving the imaging and depth of field less complicated. He did not use multichannel tape recorders but instead mixed down to stereo in real time. He achieved proper balance by careful placement of the players, sometimes having to invent ingenious setups so that the players could see the conductor.

This is rarely done nowadays because orchestra time is expensive, and it is more expedient to place multiple spot mikes throughout the stage and try to fix the problems digitally while mixing the tracks during post-production. This is made possible by the almost unlimited number of tracks available on digital recording systems, but it is always better to avoid problems in the first place. This is why so many modern orchestral recordings have a rather unnatural balance and lack image specificity and depth. He stuck with the 221B because these mics can pick up the sound all the way to the back of the stage. These advantages are clearly demonstrated by the recordings, which sound very spacious, with a large soundstage, clear and stable imaging, and good depth and balance. The instruments have natural and saturated tone colors.

Aubort was an early proponent of Dolby noise reduction. In fact, he was a friend of Ray Dolby, assumed the role of vice president of Dolby Laboratories, and was the first to adopt the Dolby A system in the US. He made full use of noise reduction to expand the dynamics of his recordings. The dynamics of this recording border on frightening at times, such as when the orchestra plays tutti, or when the tympani come in during La Valse.

Recording data for Ravel, All the Works for Orchestra.

Skrowaczewski can in turn be sensuous or atmospheric when the music calls for it, but it is never exaggerated, and he always respects the wishes of the composer, probably because he was a notable composer himself. Just listen to the atmospheric soundscape in Une Barque sur L’ocean. The spaciousness of the recording provides the perfect canvas for this impressionistic piece. The image of one of Monet’s seascapes materializes in front of one’s eyes. The perspective of the recordings is mid-hall; it is not as close as the typical Decca recording, but less far back than RCA’s. The pizzicato at the beginning of Alborada Del Gracioso has impressive speed and dynamics without sounding in your face. It is only in the tympani strikes that Aubort might have exaggerated things a little to make audiophiles happy. The orchestral playing is virtuosic, easily as good as any of the top orchestras of the day. The entries are clean and incisive, the string tone is silky, and the playing is sensitive to the subtle changes in direction. The brass section, often the weak link in an orchestra, is superb here. The sound has just the right amount of bite and intensity without sounding overwhelming.

These tapes are some of the finest in my collection, and the sound quality of the Analogue Productions-reissued LP comes close. Doug Sax paid serious attention to the quality of his equipment, down to the most minute details. He and his brother designed the whole mastering chain, which only employed tube equipment (including the tape recorders and the cutting amplifiers). The crossover he designed for his Tannoy monitors is legendary. The tonal balance and the dynamics of the LP are nearly identical to the tapes, which is really saying something, especially for a 33 RPM disc. This LP ranks along with the Classic Records-reissued Dorati Firebird on Mercury as the two most dynamic classical LPs I have heard. This LP only includes La Valse, Alborada Del Gracioso, Rapsodie Espagnole and Menuet Antique. I guess these pieces were chosen for their audiophile attributes and popularity. Too bad Bolero had not been included. Even though the LP has been long out of print, it is still quite plentiful in the second-hand market at a price not too far removed from that of the current AP reissues.

For those readers with access to an SACD player, Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs issued a multichannel SACD in 2003 that also includes Bolero, Pavane pour une infante defunte, as well as Daphnis et Chloé Suite No. 2, but without Alborada or Menuet Antique. This is a noteworthy release as Aubort set the choir in Daphnis offstage and captured the sound with two rear-facing mics for the two rear quadraphonic channels. Listeners with a multichannel set up at home will hear the sound of the choir coming from behind. This should sound even more spectacular than the original quadraphonic sound release. I have not heard the SACD, but all the reviews I have read have been positive.

Ravel, Mobile Fidelity multichannel SACD cover.

Header image of Maurice Ravel courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/public domain. All other images courtesy of the author.

0 comments