In our last installment, we looked at the range of record groove sizes that were used through the years, and we jumped ahead a bit to the launch of Stereo. In this column we’ll backtrack a bit and look at the record-tracing hardware of the Hi-Fi boom in the ’50s, leading up to the Stereo era.

Microgroove LPs brought with them new concerns regarding tracking. The lighter tracking weights (compared to 78s) increased the likelihood of the stylus jumping out of the groove due to vibration caused by footfalls or acoustic feedback. In addition, the soft vinyl compounds used for LPs were more prone to scratching than the shellac and clay amalgam used in 78s.

A new generation of phono cartridges and tonearms was needed to replace the massive arms and carts of the 78 era. As we saw back in Part 2, ground-up designs like the GE Variable Reluctance line of cartridges and the Fairchild moving coil cartridge designed by Joseph Grado, led the way in lighter, smaller, better-tracking playback gear. The sonic spectacular records often used to show off the new Hi-Fi set required more compliant cartridges to track them, in turn requiring lower-mass tonearms. Although the term “tonearm” was still used in the Hi-Fi and later stereo eras, the term no longer properly described the arm’s function, as it did in early acoustic phonographs. In those days the tonearm carried the needle and sound box which generated the sonic output; sound was then channeled down the interior of the arm, which formed a section of the gramophone’s horn.

Stronger permanent magnet materials developed during World War II made possible the magnetic phono cartridges that quickly the choice of audio aficionados of the Hi-Fi era. Cartridges like the Pickering shown in the ad above often featured turnover stylus assemblies which allowed the listener to play both 78s and LPs, at lower tracking weights and with greater precision than earlier ceramic cartridges. Magnetic cartridges had far lower electrical output than ceramics, requiring more-sensitive phono preamps with lower noise—units like the Marantz unit shown above, often referred to as the Model 1. Given the sensitivity of the phono stage, it’s a little astonishing to see the Marantz unit incorporated into a turntable base, in close proximity to the electrical and magnetic fields generated by the turntable motor. Let’s hope everything was well-shielded!

Trackability became an even greater concern with the onset of 45/45 single-groove stereo, as mistracking would be unpleasantly evident in two channels, rather than just one. In addition, mistracking could affect the channel balance, distorting or even destroying the stereo illusion. At the beginning of the era, some popular cartridges could be converted from mono to stereo. This article from Audio magazine showed how they converted one of the popular GE VR cartridges:

Cutting lathes generally moved the cutting head across the disc with a parallel-tracking arm rather than a pivoted one. Even on home record-cutting units like this Presto, such was the standard:

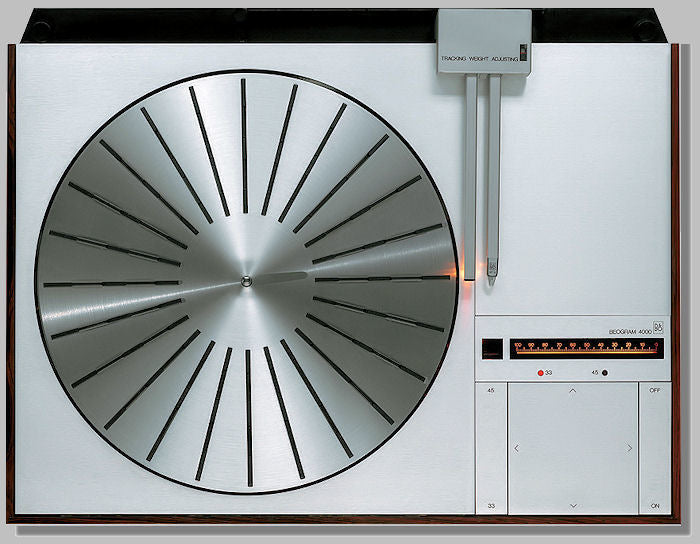

Logically enough, tonearms appeared which attempted to duplicate the action of the cutting head and eliminate tracking era. There were two basic approaches to maintaining the cartridge tangent to the groove: a true tangential arm, moving the cartridge and arm on a track or trolley across the record; or a somewhat simpler approach using a pantographic, pivoted arrangement. Both design approaches required low friction: any sticking during record playback would likely generate more tracking error than the conventional arms the parallel-trackers were designed to replace.

The tracking requirements of single-groove stereo discs heightened the interest in parallel-tracking. Even earlier mono arms like the English Burne-Jones pantographic arm were converted to stereo:

An early example of a tangential arm was the Truline—here shown with two cartridges for playing back Cook Labs binaural records:

Both types of arms still exist today, in addition to the usual pivoted arms.

In our next installment, we’ll follow the continued development of playback gear as the stereo era progressed.