In his last column, Jay Jay French mentioned the optical phono cartridge cartridge made by DS Audio in Japan. Ironically, “DS” stands for “Digital Stream”…go figure.

When you hear of an optical method of record playback, it’s easy to assume that it’s one of the laser-scanning methods that have been proposed and built over the decades—and we’ll get to those designs, eventually—but that’s not the case here. The DS cartridges track the record with a standard diamond stylus/cantilever asssembly. Inside their bodies, the cartridges contain an LED light source which is aimed at a photocell, and between those two elements is the cartridge’s cantilever. As the cartridge tracks the record, the output of the photocell is modulated by the cantilever movement, generating an output voltage which represents what’s in that squiggly groove.

Magnetic cartridges are velocity-sensing, so both increases in frequency and groove excursion cause the voltage output to increase. Photo cartridges like the DS and strain-gauge cartridges (Win, Soundsmith, others) are amplitude-sensing, responding only to the stylus’ movement. The DS and strain-gauge cartridges thus require their own particular equalization—a standard phono pre won’t work.

Here’s the interesting part about this technology: it’s not new. Philco, of all people, brought out the “Beam of Light” cartridge system on a number of products in 1941. It utilized a sapphire stylus mounted on a mirror, modulating light from a bulb—no LEDs there! They also had a 7-function wireless remote control called the “Mystery Control”—again, in 1941. You can take a look at both technologies here; on that page are links to two YouTube videos, one pretty uneventful one showing the cartridge at work, the other showing the remote in use.

From the ’40s through the ’60s (at least), the inexpensive cartridges found on most portable phonographs and other low-end turntables were of the ceramic or crystal type. Those cartridges utilized a simple piezoelectric generating element which had much higher output than magnetic cartridges, and a simple RC network provided compliance to the RIAA compensation spec. More or less, anyway—within a couple dB. Hey, they were cheap.

The post-WWII era saw the reinvention of the phono cartridge. The arrival of the microgroove LP record required the design of not just smaller styli, but the design of better tracking cartridges that would limit record wear. Stronger magnetic materials developed during the war led to smaller, lighter weight magnetic cartridges. The first major development in cartridges after the war were the VR (variable reluctance) cartridges introduced by GE in 1947, which are still highly regarded by fans of vintage audio. The cantilever moved between two pole pieces of the magnetic structure, varying flux-density of the circuit and generating a voltage in a coil. The VR cartridges originally had fixed styli; later variants had “turnover” styli for both microgroove and 78, or replaceable single styli, and in 1958, stereo versions hit the market.

The term “variable reluctance” refers to a principle of signal-generation, not a specific type of cartridge construction. To clarify: the major forms of magnetic cartridge construction are moving iron, moving magnet, and moving coil—and the moving iron types would be considered variable reluctance cartridges, as they utilize a moving element to modulate the flux in the magnetic circuit, generating a voltage.

Ortofon in Denmark had never abandoned the moving coil cartridge, which in the ’50s were sold in the US under the brand name ESL. One of the first to revive the type in post-war America was designer Joseph Grado, whose name was later long associated with moving iron cartridges. Grado was an opera singer, watchmaker and inventor; he was also a friend of hi-fi pioneer Saul Marantz, who introduced Grado to Sherman Fairchild.

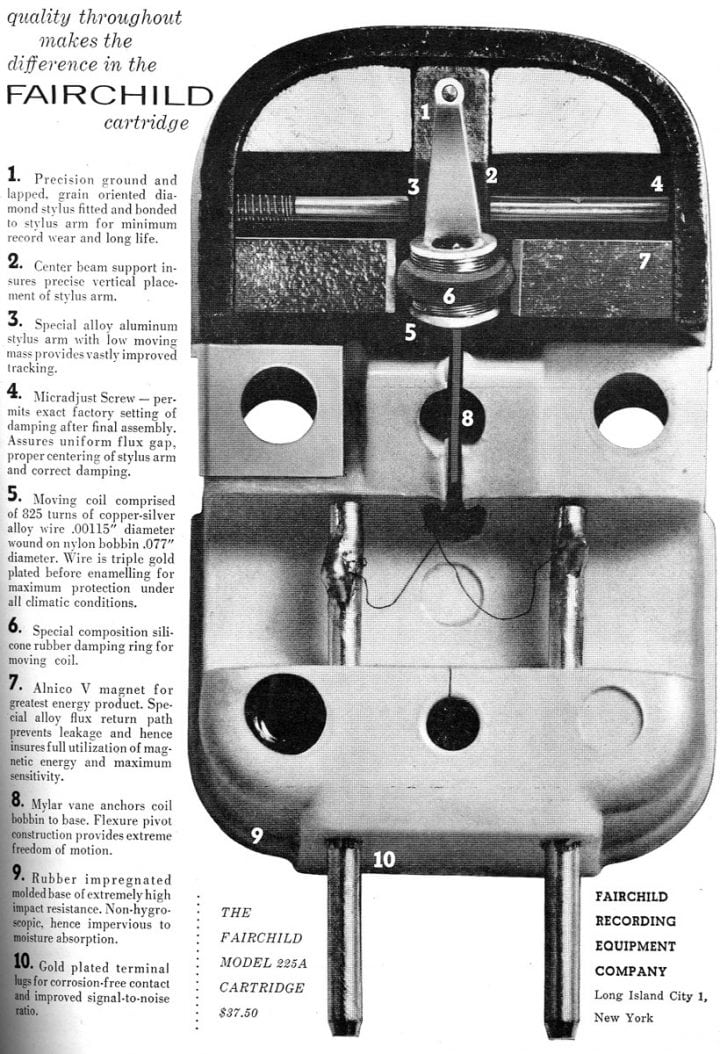

Fairchild was a multimillionaire serial entrepreneur who founded dozens of companies in many fields including aircraft, aerial photography, and the Fairchild Recording Equipment Corporation, devoted to products for professional and broadcast audio. The Recording Equipment Corporation, based in Long Island City, also dabbled in home hi-fi—and that’s where Grado went.

The Fairchild 225A, shown above, was Grado’s first audio design. He brought a watchmaker’s standards of precision and quality control to Fairchild. Within a few years, he was off on his own as Grado Labs—still in existence today, still making cartridges, although headphones are the company’s focus these days. Grado’s first cartidges on his own were also moving coils, but he soon developed moving iron cartridges with replaceable styli—the type of cartridges still made in the same brownstone in Brooklyn.

At the dawn of the stereo era, Western Electric/Westrex, developed the model 10A moving coil cartridge, a stereo version of the earlier 9A cartridge. The 10A was designed to play the single groove stereo discs developed by Westrex (discussed back in Copper #44).

The hi-fi boom of the 1950s produced a mass market for mainstream magnetic cartridges, as well as some unique technical developments in record playback. We’ll discuss both in the next issue.

0 comments