Great artists and thinkers are no stranger to controversy. Richard Wagner, Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot and Roald Dahl were all rabid anti-Semites. Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Norman Mailer – among others – were noted misogynists. Phil Spector spent the last 12 years of his life serving time in a federal prison for murder. And many of the founding fathers of America were slave owners.

Among conductors we have the example of Willem Mengelberg, who worshiped Mussolini and congratulated Hitler on his invasion of the Netherlands. Then there’s Herbert von Karajan, who joined the Nazi party not once, but twice. Even Wilhelm Furtwängler, conflicted though he was, nevertheless remained in Nazi Germany and regularly conducted in front of Hitler and other Nazi leaders. Toscanini, though a dedicated anti-Fascist, was well known to be verbally (and occasionally physically) abusive as well as being a serial philanderer. There are numerous other examples.

Which brings us to the case of the late James Lawrence Levine. The great English jurist, Sir William Blackstone famously stated (in 1769) that “it is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer.” I’ve always taken exception when I see someone convicted in the court of public opinion long before they face an actual courtroom. Nevertheless, while James Levine never had his day in court, I generally believe that where there’s smoke, there’s usually fire and there’s certainly a preponderance of evidence suggesting that the allegations of sexual misconduct are largely true.”

This raises a question that is beyond the scope of this article (and probably beyond the scope of my little brain): Why do we continue to worship artists who are so deeply flawed?

I’m obviously not going to try answering that question, other than to say that sometimes we choose to admire a great artist or thinker, in spite of their deep personal flaws.

My first experience of James Levine was in the early 1970s. Karel Ancerl, the music director of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, had recently passed away and the TSO was in the process of auditioning a series of young conductors as possible replacements. Levine conducted a program consisting of Mozart and Mahler, and I recall an extraordinarily fine performance of Des Knaben Wunderhorn, featuring Jessye Norman and John Shirley-Quirk as soloists.

Around the same time, he commenced his duties at the Metropolitan Opera and I remember traveling to nearby Detroit to hear him conduct Wagner and Smetana when the Met still did a spring tour. In those days, he was a young, brash rising star on the international music scene and his music making was muscular, full of brilliance and infectious energy. I was smitten. Through the late 1970s to the early 1990s, I often listened to WFMT broadcasts from Ravinia, Illinois, and I saw him conduct live at the Met and in Salzburg. I still cherish an electric air-check performance of the Tchaikovsky Fourth Symphony from 1983.

In that same year, Levine made the cover of Time magazine where he was lionized as “America’s Top Maestro.” He was interviewed by Charlie Rose on PBS numerous times from 1993 through 2014, and in 2011 he was profiled on American Masters, again on PBS.

But around 2010 my acquaintances in the musical world related to me the dark rumors about Levine’s private behavior that – apparently – had been circulating for some time. When those rumors became front page news in 2017, I was deeply saddened, but sadly not surprised. It caused me to reconsider my appreciation of his work.

This leads into the main body of the article. At this point, I think it’s a given that James Levine exhibited egregious behavior in his personal life and I respect anyone who has no wish, as a result, to listen to his recorded legacy. But I also believe that he was, at times, a deeply gifted artist who deserves a critical retrospective.

Prior to Levine’s very public downfall, the mainstream critical opinion seemed to be that he could do no wrong (or at least very little). Certainly, it is inarguable that he took the Met Orchestra and turned it into one of the finest ensembles in America, if not the world. He also raised the overall standards of that organization, turning it from an often-mediocre repertory house, back into one of the leading opera houses of the world. And he introduced a great deal of new repertoire. I can’t recall a single visit to the Met where he didn’t receive a standing ovation.

And that brings us to his recorded legacy. By my count, Levine recorded at least 12 of Verdi’s operas, all of Wagner’s mature operas (either on CD or video), along with operas by Beethoven, Bellini, Berg, Berlioz, Bizet, Cilea, Debussy, Donizetti, Giordano, Mascagni, Mozart, Puccini, Schonberg, Strauss, Stravinsky and Tchaikovsky, and numerous symphonic recordings. In fact, discogs.com lists 347 recordings. If that doesn’t make him as prolific as Neville Marriner or Herbert von Karajan, it’s still no small accomplishment.

Now, two years after his death and six years after his forced retirement, how do those recordings hold up to critical appraisal? I’ll attempt to summarize at the end of this article. But, for starters, I thought it would be useful to identify a handful of what I believe are James Levine’s very finest recordings. Unfortunately, many of these are either no longer available or hard to find.

Beethoven – Piano Concertos, Alfred Brendel, Chicago Symphony Orchestra (Philips): Recorded in the early 1980s during Levine’s tenure at Ravinia, these are wonderful, energetic performances; a near-perfect pairing of conductor, orchestra and soloist. Brendel was one of the finest, most thoughtful interpreters of Beethoven and that is clearly in evidence here. Levine provides a sympathetic accompaniment that is never bland. The orchestra contributes as much as the soloist, but never diminishes his role. Strangely, as I note below, Levine recorded very little Beethoven after this early effort.

Berlioz – La Damnation de Faust, Giordano, van Dam, Dalayman, Munich Philharmonic (available from ProStudio Masters in high-res audio): I would be remiss if I failed to mention Levine’s love for Berlioz. Listen, for example, to his rendering of “Queen Mab” from Romeo et Juliette (on DG). It’s a performance that Toscanini – who loved this music equally – would be proud of. Levine also led the very first performances of Benvenuto Cellini at the Met, as well Les Troyens. Technically not an opera, Berlioz called La Damnation de Faust a “dramatic legend.” That said, the Met mounted a highly effective Robert LePage production of the work in 2013, led by Levine. A recording of that performance is available on the Met’s streaming platform, as well as Apple Music. The performance referenced here is from a Munich Philharmonic concert at roughly the same time, with Marcello Giordano also in the role of Faust. I’ve listened to a number of performances of this work, and I even had the chance to sing it once (under Charles Dutoit). This is a superb exemplar.

Brahms Symphonies – Chicago Symphony Orchestra (RCA): In the middle of recording what turned out to be an incomplete Mahler symphony cycle (see below), Levine commenced the recording of a complete cycle of the Brahms symphonies, along with the Brahms Requiem. Starting with the first symphony in 1976, the critics of the day gave it ecstatic reviews. High Fidelity magazine referred to it as “once in a decade Brahms.” That judgment remains accurate to this day. While there are certainly other excellent Brahms cycles (for example, Ricardo Chailly with the Leipzig Gewandhaus or Istvan Kertesz with the London Symphony, both on Decca), this one remains a touchstone for me. Listen to the alternately propulsive and tender first symphony, with the gorgeous Chicago strings and brass, or the joyous schwung of the second symphony. You won’t be disappointed.

Dvořák – Cello Concerto, Lynn Harrell, London Symphony (RCA, no longer available): This is another early recording, dating from 1975. It’s a deeply emotional piece and both performers manage to deliver all of that emotion without making it sound maudlin. I’ve always wanted to play the cello (and no, I haven’t done it yet) but Harrell’s playing, the deep, throaty voice of his instrument, was probably the inspiration for that ambition. As with the Beethoven (above), Levine delivers a true partnership where neither the soloist nor the orchestra outclasses the other. A delight from beginning to end. If you can find an LP copy, snap it up.

Gershwin – Rhapsody in Blue, Porgy and Bess Suite, An American in Paris, Chicago Symphony (DG): Another product of Levine’s years at Ravinia, this was recorded late in that tenure in 1993, with Levine at the piano in the Rhapsody. There’s usually a certain amount of swagger in Gershwin’s music and Levine manages to bring out the best of it. Listen to the beautifully animated rhythms in An American in Paris and you can imagine Gene Kelly dancing by the banks of the Seine, or Fred Astaire strutting near the Eiffel Tower (in Funny Face). A gifted pianist as well as a conductor, Levine also delivers a virtuoso and idiomatic performance in the Rhapsody.

Holst – The Planets, Chicago Symphony Orchestra (DG): Recorded in 1989 with Margaret Hillis’ wonderful Chicago Symphony Chorus, this is one of the best-played recordings of this much-performed work. It’s not the most subtle of music, but Levine turns out a highly sympathetic performance. From the skittering strings of “Mercury, the Winged Messenger” through the pounding martial rhythms of “Mars, the Bringer of War” and the ethereal voices of “Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age,” this performance leaves nothing to be desired. Highly recommended.

Mahler – Symphony Cycle, London Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra (RCA, NLA): Alas, James Levine never completed a full cycle of the Mahler symphonies. While there are live recordings of the Second Symphony (one from Salzburg with the Vienna Philharmonic and one with the Israel Philharmonic), there are no extant performances of Levine in the Mahler Eighth, the so-called “Symphony of a Thousand.” Perhaps, somewhere in the vaults of WFMT, there exists an air check from Ravinia but, given his current reputation, it seems unlikely that it will ever see the light of day.

Unfortunately, too, the complete set which was available just a few years ago is no longer being published, although some of the individual symphony recordings are still available online. And what a shame that is. I’m not the only critic who thinks that this would have been one of the finest complete cycles had it been finished. I honestly can’t point to a single performance that isn’t among the best I’ve heard, and I own 15 complete Mahler cycles along with many individual performances.

A few highlights: the powerful opening movement of the Third Symphony, played with incredible virtuosity by the Chicago Symphony – arguably the finest Mahler orchestra in the world during the Solti/Levine years. Or there’s a mournful, propulsive performance of the Sixth symphony with the London Symphony, or another remarkable performance of the Seventh symphony, again with the Chicago Symphony. Listen, for example, to the timpani in the second movement; no one else uses them so effectively. If you’ve never heard Levine’s Mahler, you owe it to yourself to find a recording and listen. Even if it doesn’t become your favorite, I think you’ll still be impressed.

Mendelssohn – A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Blegen, Quivar, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Chorus (DG): A Midsummer Night’s Dream is one of Mendelssohn’s most charming and attractive works. It covers a multitude of moods ranging from the dancing overture to the famous wedding march and direct quotations from Shakespeare such as “Ye Spotted Snakes.” It was a favorite of Toscanini, who recorded it at least twice. Levine and his Chicago forces do it full justice with a luxury cast of singers and the usual beautiful playing of the Chicago Symphony.

Orff – Carmina Burana, Anderson, Creech, Weikl, Chicago Symphony Orchestra (DG): Another product of Levine’s Ravinia years, this was recorded in 1985. As a chorister, I have sung this ever-popular work numerous times, under numerous conductors. But I can honestly say that I’ve never experienced a performance as powerful or as well-played as this one. Listen to track 10, “Were Diu Werlt Alle Min,” and see if you’ve ever heard more brilliant orchestral playing or crisper choral singing. This is a performance that brings this much-hackneyed work to life.

Prokofiev – Symphonies 1 and 5, Chicago Symphony Orchestra (DG): While there are arguably finer performances of the Prokofiev “Classical” Symphony (for example, Neville Marriner and the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields on Argo – unfortunately no longer available), this one is still admirable and I have yet to hear a performance of the Fifth Symphony that has the motoric energy and drive of this performance, along with the fabulous playing of the CSO. I’ve listened to many performances of this symphony and this remains my favorite.

Schubert – Ninth Symphony “The Great,” Metropolitan Opera Orchestra (DG): This is part of a 2-CD set which also contains a performance of the Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 4 with Evgeny Kissin, and other works. It’s also a rarity on this list as it comes from very late in Levine’s career, a live concert at Carnegie Hall in 2013. Levine’s earlier recording of this symphony, with the Chicago Symphony, is certainly carefully crafted but frankly also undistinguished. Not so with this effort. The great Symphony No. 1 in C Major is a mountain to climb; Robert Schumann wrote of its “heavenly lengths” and in the wrong hands it can feel long and tedious. Fortunately, that’s not the case here. Levine shows a real understanding for the structure of the work and draws gorgeous playing from his Met forces.

Schumann – Complete Symphonies, Philadelphia Orchestra (RCA): Recorded in 1981 during Levine’s Ravinia years, but not with the Chicago Symphony, this is the earlier of his two traversals of the Schumann symphonies (the later one is with the Berlin Philharmonic on DG). Schumann’s symphonic works are challenging. I remember that, when I first heard them as a teenager, I found them tedious. It takes a special conductor to bring them to life and Levine succeeds at this, quite brilliantly. My favorite of the cycle (although all the performances are good) is the Second symphony where Levine somehow manages to get the tempi, rhythm, dynamics, and phrasing just right, resulting in a performance of tremendous energy and elan. A pleasure to listen to and enjoy.

Smetana – Má Vlast, Vienna Philharmonic (DG): I own several recordings of this seminal work by arguably the second best-known Czech composer (after Dvořák). Those include a marvelous, albeit ancient recording by the late Karel Ancerl which, despite its age, shows a near-perfect understanding of the idiom. For a performance with more modern sound, this recording by the glorious Vienna Philharmonic does the trick. When you consider that Bratislava is less than an hour ride from Vienna, you realize that this music is also very much connected to the Viennese traditions. Early on in his career at the Met, James Levine led an English-language version of The Bartered Bride, an opera that was seldom heard at that institution. I saw that production on the Met spring tour and I fully understood why it received rave reviews at the time. Levine clearly has a deep connection with this composer and it shows in the above performances.

Tchaikovsky – Eugene Onegin, Lang, Freni, von Otter, Allen, Staatskapelle Dresden (DG): Perhaps you’ve noticed that, even though James Levine was best known as an opera conductor, I haven’t mentioned a single opera until now. There are several reasons for this. The first is technical: many of the operas that he recorded were by Verdi or Wagner and we haven’t got that far in the alphabet yet. But it’s also worth pointing out that many of the operas that James Levine performed were only recorded as DVD videos. And while the sound quality on those videos is not bad, it’s generally not up to the same standards as an audio-only recording. And finally, as I’ll discuss below, I’m not particularly impressed with his performances of Mozart.

In any case, this recording of Tchaikovsky’s best-known opera is superb. Strangely, for such a well-known opera, there are relatively few recordings in the catalog, apart from several recorded in Russia. Nevertheless, this performance, I think, captures all of the nuances of this highly emotional work. The dance sequences are played with great joy and the singing throughout is excellent. Since I don’t speak Russian, I can’t comment on the largely non-Russian cast’s diction, but from my limited knowledge, it sounds solid. The Staatskapelle Dresden, unsurprisingly, plays beautifully and DG’s recording, if a bit closely miked, is very fine.

Tchaikovsky – Sixth Symphony, Chicago Symphony Orchestra (RCA): I’m going to go out on a bit of a limb and tell you that this is not my favorite performance of this symphony. However, that said, I think it is nevertheless an excellent performance, one which deserves a hearing. Once again, this was recorded during the Chicago Symphony’s Solti/Levine years and the power and precision of the orchestra is beyond reproach. Maybe you favor a more super-heated performance like that of Evgeny Mravinsky, or perhaps something a bit cooler like Lorin Maazel with the Vienna Philharmonic. But this performance seems to strike a balance between those extremes.

Verdi – Aida, Milo, Domingo, Morris, Ramey, Metropolitan Opera (Sony Classical): James Levine recorded at least a dozen of Giuseppe Verdi’s operas during his tenure at the Met. So why did I home in on this particular recording? The truth is that I’m not particularly moved by early or middle-period Verdi. That’s just my personal taste and it’s only when we get to Aida, Otello and Falstaff that I really understand his genius. Levine made a very fine recording of Otello, but this recording – I believe – is his finest achievement in Verdi. Boasting a luxury cast at or near the height of their powers, along with the Met Orchestra playing its heart out, this is a beautifully-recorded and played performance. There are many fine recordings of Aida, but to my ears this is one of the best.

Wagner – Parsifal, Vickers, Ludwig, Weikl, Talvela, Metropolitan Opera Orchestra (available for Met subscribers or on Soundcloud): Parsifal was one of James Levine’s specialties. He conducted the centenary production at Bayreuth and recorded it twice: once with the Met, along with a recording of the Bayreuth performances. There are also several live performances preserved by the Met, and this is probably the earliest one. Someone once remarked that one of the musical mysteries of the 20th century is the fact that performances of Bach became faster while performances of Wagner became slower. That can also be said of Levine’s performances of this opera, which became generally slower over the years. For an interesting comparison, listen to Pierre Boulez’ comparatively speedy traversal from the 1970 Bayreuth Festival.

In any case, the performance noted here may lean toward the slow side but it is a lovely reading, bolstered by a cast consisting of some of the leading Wagnerians of the latter half of the 20th century. While Jon Vickers may have been approaching the end of his career, he is still in fine voice here and, in any case Parsifal is not Siegfried. It makes easier demands on its protagonists. And what protagonists they are! Christa Ludwig is a near-perfect Kundry and Bernd Weikl inhabits the role of Amfortas. While this was recorded relatively early in Levine’s tenure at the Met, he still manages to draw lustrous playing from the orchestra.

If there’s a common thread to all of the above, it is that the majority of these recordings were made relatively early in Levine’s career, during the period when he was active at Ravinia during the summer. You might note that I included none of his recordings with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and only one from his Munich Philharmonic years. This is not to say that any those recordings are bad. However, at least according to this listener, few of them stand out in a critical comparison, with the exception of the Berlioz, above, and the possible exception of his Mahler Sixth Symphony with the BSO.

You’ll also notice that the vast majority of these recordings are of music from the romantic period. Levine performed and recorded a lot of Mozart and I attended performances of Die Entführung aus dem Serail and La Clemenza di Tito. But, at least on record, I never found that those performances went much beyond competent.

So what about the rest of those 347 recordings – the ones I didn’t mention? I have a few observations about those. First: on several occasions, Levine re-recorded works that he had recorded earlier in his career. In every case that I can think of, the earlier performance is preferable. For example, I find the Schumann symphony cycle that he recorded with the Philadelphia forces has more rhythmic drive and inherent drama than his later cycle with the Berlin Philharmonic. And that’s important because, frankly, Schumann’s symphonies are not the most exciting works in the symphonic repertoire. I find the same thing is true with Levine’s recording of the Brahms symphonies with the Vienna Philharmonic. To my ears, the Chicago Symphony performances, recorded nearly 20 years earlier, are less fussy and more kinetic.

Second observation: there are strange holes in Levine’s recorded legacy. He made a commercial recording of only one Beethoven Symphony – the Eroica, with the Met forces (although there is a live performance of the Seventh symphony on Oehms from his years at the Munich Philharmonic). As I mentioned earlier, he never made a commercial recording of the Mahler Second or Eighth symphonies and he recorded only a single Tchaikovsky symphony – the Pathétique, even though I know he performed the Fourth. He recorded many of Verdi’s operas but strangely, not Falstaff, even though he performed it frequently.

And finally, this: for all his brilliance when he was “on,” some of his recordings – to this listener, anyway – sound rather anonymous. I mentioned Mozart earlier. To my ears, his recordings of Le Nozze di Figaro and Cosi fan Tutte, are beautifully played and sung and, I suppose, if I heard those performances in the opera house, I would have been quite impressed. But upon repeated listening, I find them somewhat flat and uninteresting. Compare, for example, Rene Jacobs’ performances on period instruments, which have a sparkle that seems to be missing from the DG recordings with the Met.

That same criticism could also be leveled at a number of Levine’s other recordings. I will observe, for example, that his recordings of Wagner could be uneven. I listened to his DG Ring Cycle only once. While it had some lovely moments, there was nothing that caused me to return to it since that first experience. Funny enough, I recently came across his live performances of the Ring from his time at Bayreuth in the mid-1990s (on YouTube). Those performances, to my ears, were far more alive and dramatic.

The reality is that no conductor is ideally suited to every musical work (with the possible exception of the late, great Carlos Kleiber, who conducted an extremely limited repertoire). Even Furtwängler and Toscanini had their off days. And the art of music is, of course, a matter of taste. You may prefer von Karajan where I prefer Bernstein. That’s understandable. But in the case of James Levine, my conclusion is that while he was a flawed human being, he was also a musician with enormous gifts that were, nevertheless, not always on evidence. At his best, his performances and recordings were transcendent, and at his worst, merely competent. Ultimately, you – the listener – will have to decide where he stands in your listening canon.

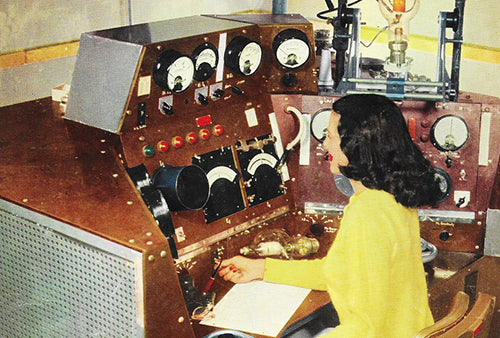

Dig that crazy test fixture on her right. And does that switch on her left turn the whole rig on and off? Radio and Television News, October 1950.

Dig that crazy test fixture on her right. And does that switch on her left turn the whole rig on and off? Radio and Television News, October 1950.