They may have shortened their name, but the Chicks are still as long on talent as they were when they started their country band in Dallas more than 20 years ago. While they have never shied away from controversy, they also have the musical chops to stand up to any contemporary country musicians.

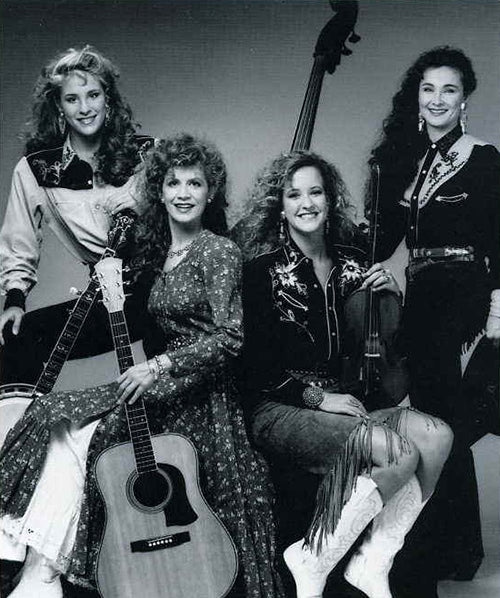

In 1989, Dallas natives Martie Erwin (now Maguire) and Emily Erwin (now Strayer) joined bassist Laura Lynch and singer-guitarist Robin Lynn Macy to start a country and bluegrass group. They called themselves the Dixie Chicks, a tip of the hat to the Little Feat song “Dixie Chicken” by singer/songwriter Lowell George. Eventually that name would start to haunt them, but at the time it seemed like a perfect sobriquet for a quartet of Southern women.

They were gifted instrumentalists. Maguire, an award-winning fiddler, also played guitar and mandolin, and Strayer played guitar, banjo, and Dobro. Lynch and Macy took the lead vocals. Despite their talents and determination, they got off to a slow start commercially. Their first album, Thank Heavens for Dale Evans (1990), was independently produced and funded through the generous donation of a friend. This was long before indie and DIY records were viable on the marketplace.

Only a few of the songs were original, including the title track. The rest of the album consisted of traditional tunes and covers. Probably because the budget was so small, most of those are by lesser-known artists, like Lynnda Goza’s “The Cowboy Lives Forever,” but there is one Patsy Cline song, “I Want to Be a Cowboy’s Sweetheart,” plus Sam Cooke’s “Bring It on Home to Me.”

The debut leans heavily toward bluegrass, featuring mountain harmony in the vocals and some fine picking and fiddling, as on “Green River.” The mandolin solo is by local champion player Dave Peters.

It’s not unusual for world-famous bands to start out small, but most have found their footing by their second album. Despite a couple of high-profile TV appearances, the Dixie Chicks were still self-funding and decidedly not famous when they made Little Ol’ Cowgirl in 1992. A notable difference from the first album, however, was the number of session musicians and the complexity of the arrangements. One of those musicians was Lloyd Maines on steel guitar; his daughter Natalie Maines would eventually become the Dixie Chicks’ lead singer.

Little Ol’ Cowgirl is already pushing the boundaries of the band’s sound, putting Ray Charles’ gospel-influenced “Hallelujah, I Love Him So” next to a trad-jazz original, “Pink Toenails” and the neo-bluegrass “Aunt Mattie’s Quilt.” On Bob Millard’s “She’ll Find Better Things to Do,” they show how well they’ve absorbed the classic country sound.

Macy was not happy about the expansion of the band’s musical vision. She wanted to be a bluegrass singer, pure and simple, so she left. Rather than replace her for Shouldn’t a Told You That (1993), the others altered their name to The Dixie Chicks Cowgirl Band and proceeded as a trio. Again self-funded, this album has a somewhat scaled-back personnel list – most obviously, there’s no brass.

The track list is eclectic, but with an emphasis on newer works by young colleagues in country, such as “There Goes My Dream” by Jamie O’Hara of The O’Kanes and the title song by Walter Hyatt, leader of the trendy Uncle Walt’s Band. The slickly produced “Desire” was written by Steve Kolander, who had yet to release his first album.

The five-year gap between the third and fourth albums was full of changes. Lynch left to get married. With only two musicians and no lead singers remaining, it was time to regroup. They took on Natalie Maines. Just as important was the interest in them by Sony’s Nashville branch. Soon they had their first major record deal. Not surprisingly, their next album, Wide Open Spaces, opened up the market for them. With professional guidance, even their clothing changed: they set aside the cowgirl outfits they’d always worn as a gimmick and went with modern clothes.

Maines did not play bass, so they used session musician Michael Rhodes. On the other hand, Maguire and Strayer were both expanding their instrumental expertise. Strayer now added sitar and accordion to her skills, and Maguire branched out to viola and mandolin. One of the highlights of this top-selling album was the Chicks’ cover of Bonnie Raitt’s “Give It Up or Let Me Go.”

Wide Open Spaces won the Grammy Award for Best Country Album, and its single “There’s Your Trouble” gave the group the first of its five Grammys for Best Song by a Duo or Group. Their commercial success increased with Fly in 1999. That record’s distinctive sound comes from the string orchestra arrangements by Dennis Burnside. More than half the songs on Fly charted, including one that hadn’t even been released as a single.

Having signed with Columbia Records, the Dixie Chicks meant it when they called their 2002 album Home. Back home to their roots, that is, to frolic in the sounds of bluegrass again. At the same time they went back to tradition, the band also stepped out into a new political light when Maines publicly criticized George W. Bush for invading Iraq. This happened just as their single “Travelin’ Soldier” reached the No. 1 spot; radio stations across the country boycotted it in protest, which quickly killed it on the charts.

Among the typically eclectic mix of songs chosen for Home is the original, “Tortured, Tangled Hearts,” which Steyer and Maguire cowrote with country legend Marty Stuart. Although Stuart does not play on the track, the band is joined by two top-flight mandolinists, Chris Thile and Adam Steffey; Maguire’s fiddling has no trouble keeping up.

The Chicks’ best-debuting album so far is 2006’s Taking the Long Way, which started at the top of the charts. Its opening song and biggest single, “Not Ready to Make Nice,” deals with the anti-war controversy of the previous album, thus concretizing this band as proudly political.

At this point, they took a long hiatus from the studio, although they toured some and put out a couple live albums. Streyer and Maguire also performed during this period as a duo called Court Yard Hounds. And they remained politically active.

Their most talked-about recent political act was to change their band’s name in 2020; they have claimed that this change had been in the offing for years. Having seen a Confederate flag described as a “Dixie Swastika,” they finally had enough of that Southern term, believing it too closely associated with slavery in America. They dropped the word and are now simply the Chicks.

The Chicks’ most recent album (and the first to use their new name) is Gaslighter, released in 2020. It was their first studio release in 14 years. The songs are more about Maines’ divorce than the unrest of the wider world. But they’re still powerful, and they still display the musical skill expected of these enterprising women.

Header image: the Dixie Chicks, early promotional photo.