Ideally, the recording would be an identical representation of the acoustic reality, the transfer to the master disk would be an identical transfer of the recording and the plating and pressing process would yield vinyl records containing grooves identical to those on the master disk, with nothing added and nothing removed. The reproducing system would then translate these grooves back into the original acoustic reality, right there in your living room. Reality, however, always interrupts us before we reach this ultimate nirvana.

Microphones, loudspeakers, cutter heads, cartridges, magnetic tape heads, electronics, and all other components of recording and reproducing systems are still far from perfect. They do, however, allow a subjective element, which may compensate to some extent for the inability of the technology to really capture and subsequently reproduce the exact original acoustic reality in a different space at a later time, through the selection of the most appropriate microphones, their placement, pairing with certain electronics, adjusting controls, and so on. Likewise, the selection of loudspeakers, their placement in the room, and choice of electronics, cables and other accessories, introduce a subjective element, which will best serve to create the illusion that even if this is not the original acoustic reality, it is getting impressively close to it.

In plating and pressing, however, we are dealing with industrial mass-manufacturing processes and manufacturing tolerances. It is no longer possible to adjust parameters of the sound in the sense of adding more bass or having any other form of creative control.

The ideal of vinyl records identical to the master disk can never be achieved due to the inevitable manufacturing errors. Each plating and pressing facility needs to be set up with a certain target for manufacturing tolerances and keep their process parameters under control to repeatably and reliably turn out products that fall within these tolerances.

Working to extremely tight tolerances means that the product is more consistent, accurate, and truer to the master disk. In such cases, the errors can be kept so small as to be practically below the threshold of perception, resulting in a product that is, both subjectively and even objectively (via measurements), extremely satisfactory.

However, tight tolerances require tight process parameter control, more elaborate equipment and facilities, a more skilled workforce, better raw materials, and inevitably, a higher rejection ratio. This last point is often not properly appreciated. Even the finest facilities will produce records that are out of spec. When they do, they will usually quickly realize and make the necessary adjustments to bring things back to normal. However, there will still be some out-of-spec records, and a choice to be made: “are these to be sold to the customer along with the good ones, hoping nobody will realize, or are they to be destroyed?” This question can be rephrased as follows: “who pays for these out-of-spec records, the customer directly, or the customer indirectly?”

In the end, the pressing plant is there to serve the demand for a certain product. It is the customer who needs the product and pays for whatever it takes to manufacture it to their standards. If their standards are high and to have 1,500 records of acceptable quality, a total of 1,000 records must be manufactured, 500 of which must be rejected for failing to meet these high standards, then the customer should be prepared to pay for 1,500 records, the high-quality raw materials, the more elaborate parameter control, and the skilled individuals who can make this happen. They will either pay this upfront, by choosing a better (and more expensive) pressing plant who will be honest about what is needed, or they can choose to pay less for a plant that will deliver inferior records, reject, then pay more to have more pressed, reject some more, pay some more, and so on. At this point in their learning curve, many record labels decide to just sell the inferior records and not care about it, if they believe their customer base will accept this.

Some people prefer to waste their money in small increments. Others invest it more wisely in larger chunks. The exact same applies to the consumer. If you really do want excellent records, you will have to be willing to pay for what it takes to make them. Neither the record label (or artist who self-releases), nor the pressing plant, mastering facility, or recording studio will absorb the increased cost of higher quality. If consumers are not willing to pay for higher quality, nobody will.

But let us leave the economics aside and see what happens after the master disks have been cut.

Master disks are soft, fragile, and contain microscopic grooves of nano-scale detail. We need a way to replicate this groove structure accurately on multiple vinyl records. The general concept is that we need to first make a durable “negative” of the master disk, containing ridges instead of grooves, and then use it to “stamp” this structure as grooves on plastic records. Unlike the rubber stamps we use with ink on paper, record grooves are 3-dimensional and the geometry is critical.

To further augment this piece with the latest trendy keywords, the “negative” is made using an additive manufacturing process frequently associated with nanotechnology: electroplating! (And has been done this way for over a century!)

But first, the master lacquer disks must be visually inspected for defects and then be thoroughly cleaned and chemically treated.

Then they are sprayed with silver nitrate to give them a thin conductive coating. This step is called “silvering.”

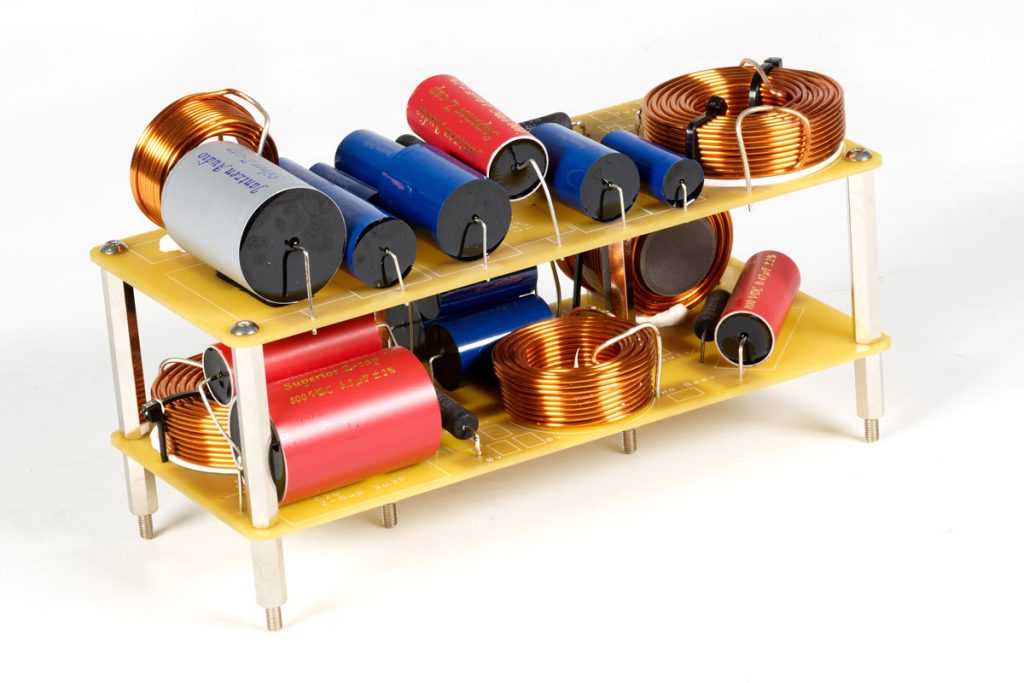

The silvered master disks are then immersed in a galvanic bath where they are plated with nickel. This is a very tricky process. The nickel negative is slowly “grown” through electrodeposition. The bath temperature and rate of deposition are critical parameters for accurate plating. Getting these wrong can ruin the master disk and/or the negative. Doing it too fast introduces stresses and defects. Doing it too slow increases the cost and lowers productivity.

When the negative has been grown, it needs to be carefully separated from the master disk. The master disk, at this point, has fulfilled its goal in life, and with surface damage from the separation of the nickel negative, can no longer be used. The negative could now be used directly to press records, but it would only be able to press around 1,000 to 1,500 records at best, before it gets worn out. No longer having the master disk available, this would be too risky and uneconomical. Instead, we usually call this negative a “father,” clean it, chemically treat it and dunk it in a galvanic bath to plate it. A nickel positive is grown on it, this time having grooves on it. This is separated from the “father” and we call it a “mother!” The mother can be inspected under a microscope and it can also be played on a turntable with certain precautions to prevent damage. Anyone who has ever heard a metal mother is left wishing we could just make 1,000 metal mothers instead of vinyl records! In fact, we can, but be prepared for a four-figure retail price. But, less friction between groove and stylus and no deformation distortions translate to improved transients, high-frequency response, and lower distortion. However, nickel is ferromagnetic, so we would be limited to using moving magnet and moving iron cartridges. I do have ideas about this, but they would be dismissed as rabidly uneconomical by any MBA with even the slightest desire to fit in with the mainstream…!

So, the mothers get cleaned, chemically treated and sometimes even de-horned, de-ticked, and polished, before being placed back into a galvanic bath to grow another negative, which we call a “son” or “stamper.” A mother can grow several “sons,” since she is tough and resistant to separation damage (as long as the person doing the separation actually knows how to do it). Happy family moments!

Stampers then need to be accurately centered. This is what defines the centering of a record. The centering is done by observing the runout on the locked groove under a measurement microscope and adjusting a turntable stage until it is deemed acceptably centered. At that point, a center hole is punched, but not a small one for a turntable spindle! The stamper is held on the molds of a press, through a larger center hole and around the perimeter.

The stamper is sanded on the back and label area and formed on a pre-former, giving it the necessary contour around the edge and center for the mounting hardware on the press.

Two stampers are fitted on a press, one for each side of the record. Raw PVC is formed into soft pucks, often called “biscuits”, through an extruder. A puck is sandwiched between two round paper labels (already printed and dried in an oven) and inserted into the press, between the two stampers. Steam heats up the molds and a hydraulic system presses the puck into a flat record with the grooves stamped on it. Then the steam is shut off and water runs through the molds to cool them and solidify the record.

PVC is a thermoplastic, so it softens with heat and hardens again when cooled. At the end of the cooling cycle, the press opens, the record is removed and is moved to the trimmer table, a turntable which clamps and rotates the record while the edge is trimmed. After the edge trimming, the records are stacked on cooling plates and left there to fully cool down and stabilize, sometimes for over 24 hours.

The timing of the steam and water cycle, the pressing force, the hydraulic system and steam pressure, the extruder settings and the puck temperature are all critical. Improper compression-molding parameters result in noisy records with high distortion, warps, and many other defects. In particularly bad cases, the result can even be damaged stampers and molds, or toxic fumes from overheated PVC. Rough edges can result from bad trimming, dents can appear on the record surface as a result of worn molds or stamper mishandling, while inadequate time on the cooling plates results in warped records.

The first few records are considered test pressings and are sent to those involved in the production of the record for evaluation and approval, before the proper manufacturing run commences. Usually, this evaluation is done on accurately-calibrated reproducing systems, by the producer, record label executives, mastering engineer (for a technical perspective), and occasionally also the artists themselves. This is the first opportunity these people have of actually listening to what has collectively been achieved in disk mastering, plating, and pressing. If any problems are found, they have to be traced back to their source and rectified. In case the fault occurred prior to the mothers, the entire process has to start all over again, with the cutting of new master disks. When planning a high-quality release, an adequate budget must be set aside to cover the event of unforeseen problems. It could be that masters will need to be cut more than once, if need be, to maintain the desired level of quality, along with additional plating runs and more test pressings.

Once the test pressings are approved, the manufacturing of the final product can start. It can range from a few hundred to a few thousand copies. For international hit albums selling millions of copies, stampers are sent out to pressing plants in many different countries. Then comes the real challenge: quality control of thousands of records, within a reasonable time frame and budget! We shall discuss this topic in the next episode.

All images courtesy of Magnetic Fidelity except where indicated.

This article first appeared in Issue 93.