Different time periods in history are associated with particular architectural trends, building techniques and construction materials, different stages of technological development, as well as different styles and forms of musical composition.

Architectural trends had a significant influence on the spaces intended for the performance of music during different time periods and together with the techniques and materials employed, shaped the acoustics of these spaces. As such, each time period and geographic location had a particular acoustic signature, whether intentionally shaped or accidentally occurring as a result of the materials, methods, or ideas of the time.

When a musical composition is performed, the result is ultimately affected by the interpretation of the work by the performers, the sound produced by their instruments, and the interaction of that sound with the acoustics of the performance space. Performers adjust the nuances of their playing during a performance, based on what they hear, as a form of closed-loop auditory feedback control process. This is a near-instantaneous process which happens almost instinctively. Composers, on the other hand, adjust and refine their compositions over a long period of time, usually based on their auditory experience of performances. The logical extension of these relationships is that the different composition styles and forms of different time periods were influenced by the performance space acoustics of the time.

Up until the late 19th century, music could only be heard in the form of a live performance. The invention of sound recording changed everything. It introduced an entirely new possibility for experiencing music, by reproducing a recording of a performance, which happened in a different place, at a different time.

In sound recording, the medium and process can be thought of as an equally influential factor, as the performance space is to a live performance. Each recording medium, with its strengths, weaknesses, and limitations, affects the way in which the listener will perceive a certain composition and performance. It will therefore also affect the nuances of the performer, who will try to adjust their performance to the medium and its particularities. Over time, sound recording technology has influenced composition styles, arrangements, and performances.

The recording process actually starts with the composition. In a moment of inspiration (and/or years of refining), someone needs to compose the music. An outstanding composition can still be ruined in subsequent stages, but a mediocre composition cannot be made less mediocre by the rest of the process. It can only go downhill from there.

Once we have an outstanding composition, we need an outstanding arrangement, done by an arranger with experience of the record production process, to ensure the original intentions of the composer are properly represented in recorded form.

Then, of course, we need some excellent musicians who can perform the arranged composition with skill and virtuosity. In turn, they will need outstanding musical instruments to perform on, built by highly skilled craftsmen to sound stunningly good, based on centuries of tradition and pride in one’s craft, using the finest materials and tools available.

The actual performance must then take place in a space with acoustics suitable for the composition, but also for the recording process, adequately protected from external disturbances through soundproofing, while still maintaining the required acoustic signature within.

It is all of the aforementioned factors that will ultimately define the sound of the recording, if everything is done right. The aim of the engineers involved in the rest of the process is (or should be) to ensure that all of the collective excellence achieved thus far is properly represented and preserved up until the final product. If any of this excellence is missing, no amount of “engineering” or technical gadgetry could ever truly make up for it. Recording technology allows us to capture what is there, if we are skilled enough at using it to its full potential, but will not make the source sound better than it is, nor will it improve the composition, arrangement, or performance. Under certain circumstances, it can be used to mask some flaws or edit out mistakes, but there will always be serious side-effects. In other words, sound recording technology is not a substitute for skill, effort, quality, and intelligence. But it is a tool, that, when used in combination with skill, effort, quality, and intelligence, may allow us to preserve all this in recorded form.

This is done by means of microphones, strategically placed in the performance space of the recording facility. These convert the sound into electrical signals. The accuracy of this conversion depends on the quality of the microphones and their careful positioning in the space. The electrical signal produced by a microphone is rather weak, so a microphone preamplifier is used to amplify it, as accurately as the overall design and build quality of the preamplifier will allow.

Technically, all we need for an outstanding stereophonic recording is two microphones, one for the left and one for the right channel, two microphone preamplifiers, and the stereophonic recording device. A recording setup can range from being as simple as that to as complicated as hundreds of microphones, microphone preamplifiers, signal processing units, huge multi-channel mixing consoles, multitrack recording devices, effect units, artificial reverberation, multiple stages of re-recording, editing, adjusting, and so on. But less is usually more in this field. Even the finest audio equipment will introduce some signal deterioration, which may be insignificant on a high quality specimen. However, these “insignificant” deteriorations are accumulative and quickly become significant when a large number of devices are being used.

In practice, we also need a source of power for our equipment. This point is frequently overlooked, but electronic amplification actually works by modulating the power supply DC in proportion to the audio signal. The power supply is therefore of major importance to the overall accuracy of all audio electronics, but it also needs a clean and stable source of electricity, usually in the form of AC, which it would then convert to DC. Especially in these murky times of distributed generation and tons of cheap digital gadgets, electricity supplied through the grid contains all kinds of muck you certainly wouldn’t want anywhere near your audio equipment. The more serious professional audio facilities go to great lengths to ensure their equipment is powered from a clean supply. At Magnetic Fidelity, an analog recording and mastering studio I designed in 2014, I installed an elaborate microgeneration system, isolated from the grid, to power all the audio equipment. It runs on a massive battery bank, offering several hours of autonomy in case of electrical faults upstream, to ensure critical sessions will not be interrupted.

The analog audio electronics get a dedicated supply. The tape machine, turntable, and disk recording lathe motors, with their control electronics, get their own supply, isolated from the audio electronics. The lights, air conditioning, ventilation, fridge, and office equipment are powered by electrically isolated lines, going so far as to make sure that “dirty” power lines are not even physically located near the mastering room. Multiple stages of EMI/RFI filtering are in place and the grounding was given special attention to prevent ground loops. The “audio power” is distributed in a balanced fashion, where instead of “line” and “neutral”, there are “positive” and “negative” conductors, carrying identical voltage but in opposite polarity, running as twisted pairs.

In domestic listening rooms, the situation is much easier to cope with, as the power requirements are usually more modest, there are fewer pieces of audio equipment, shorter distances (all equipment is usually located in one room) and plenty of suitably sized power conditioners/filters/resynthesizers available to choose from.

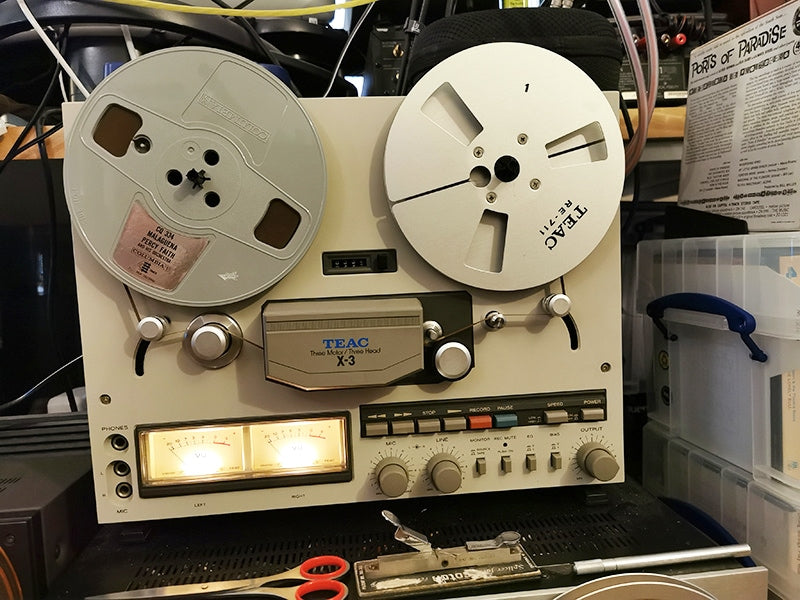

Last but not least, the recording device itself also introduces side-effects, be it mechanical (disk recording lathe), magnetic (tape machine), or digital (Analog to Digital Converter). There are a lot of claims and outright lies regarding the “accuracy” of different sound recording technologies, but this is a topic for an entire book.

Having extensively used a large number of the world’s finest professional recording devices and doing A/B comparisons between the source signal and the recorded/reproduced signal, on exceptionally accurate full-range monitors, I can confidently state that there is no such thing as a truly transparent recording technology or device.

They all affect the signal, audibly and measurably. The better sounding ones affect it in ways which are less perceptible to our auditory system.

As such, I prefer to only use one recording device and avoid re-recording or mixdowns. But, this can only be achieved if the (excellent) musicians can (excellently) perform the (excellently arranged) composition, all together, like they used to do in the good old days. This makes any deficiencies in the recording equipment more blatantly obvious, so excellent equipment must be used, controlled by an engineer who absolutely must “play along” with the musicians and get everything right, on the spot, to succeed in really capturing the magic of the moment.

The development of sound recording technology past the 1930s was not always in the interest of more accurately preserving the magic of a performance.

For instance, it was customary to use two copies (on disk) of a recorded political speech on two turntables, with a mixer (pretty much what the DJ culture rediscovered much later) in between. One record was playing while the other was “cued” (stopped with the needle still on it at a particular spot), so the operator could skip a few words or sentences by switching in the cued record at the right moment and switching out the first one, thereby changing the message conveyed, to serve political propaganda requirements.

During the second world war, Germany invented plastic tape with a magnetic coating and combined it with AC bias recording, creating a high fidelity sound recording system which allowed far more elaborate editing. The tape could be cut with a razor blade and another piece of tape could be spliced in, anywhere needed, perfecting the art of political propaganda by making it possible to piece together a speech, word by word, using the recorded voice of any politician.

Obviously, elaborate editing possibilities were not exactly needed to fix an outstanding performance. Likewise, multitrack recording was not invented to enable a well coordinated group of musicians to perform each instrument individually, artificial reverberation was not invented to “spice up” the sound of a hall with great natural reverberant acoustics, and autotune was not invented to electronically tune the voice of Montserrat Caballé! It is well-tuned enough as it is, thank you!

As the dividing lines between composer, arranger, performer and engineer are becoming increasingly blurred, as traditional instruments are being replaced by synthesizers, software, and even recording/reproducing devices (not a new development, have a listen to Joe Meek and the Blue Men– I Hear a New World) and as our modern technology allows anyone to edit, tune, reverberate, loop, overdub, and layer sounds for a nominal investment, it is easy to forget that the basic principles and rules outlined earlier, still apply, regardless of style of music, choice of instruments, and type of recording technology used.

The sound of a recording is still defined by the composition, arrangement, performance, instruments, and acoustics of the space, which the recording equipment and engineer can either succeed in adequately capturing, or not.

This applies equally to all styles of music and anything one may decide to use as an instrument.

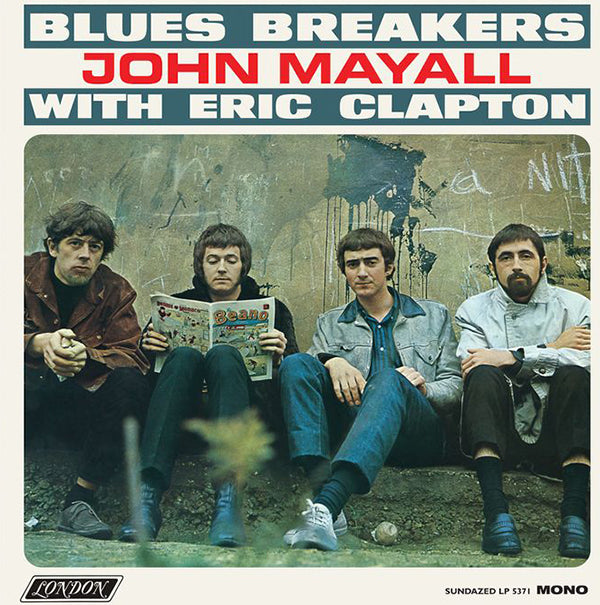

Here are two beautiful examples of two rock bands, performing all together, recorded on a stereophonic 1/4″ tape recorder, using a very minimal setup:

Lunar MGC – “Planemo”

Naxatras – “Machine”

Amidst promises of making space colonization viable within the next five years, I personally feel there is a lot of untapped potential right here on our modest planet; musical treasures yet to be discovered and preserved, if only we could remain a bit more “down-to-earth” about the whole thing.

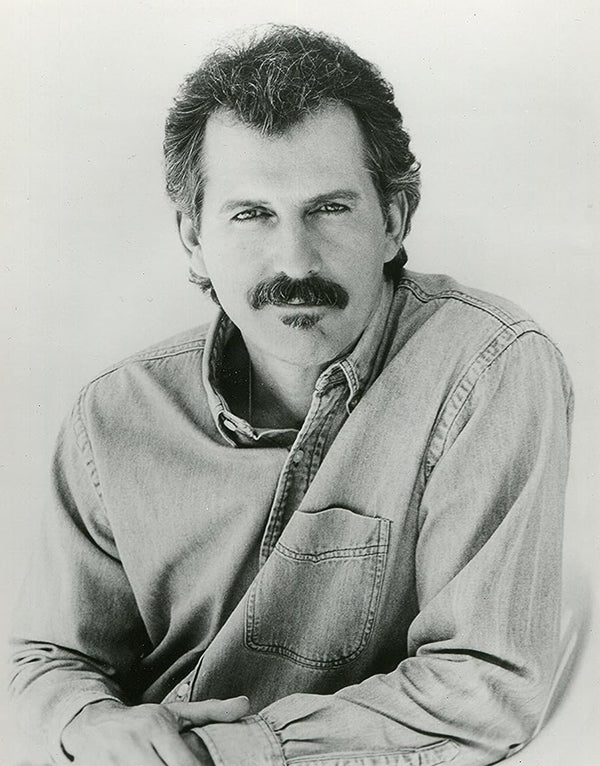

Header image: Naxatras recording session at Agnew Analog Reference Instruments, courtesy of Elina Verykiou.

This article first appeared in Issue 91.

Courtesy of

Courtesy of