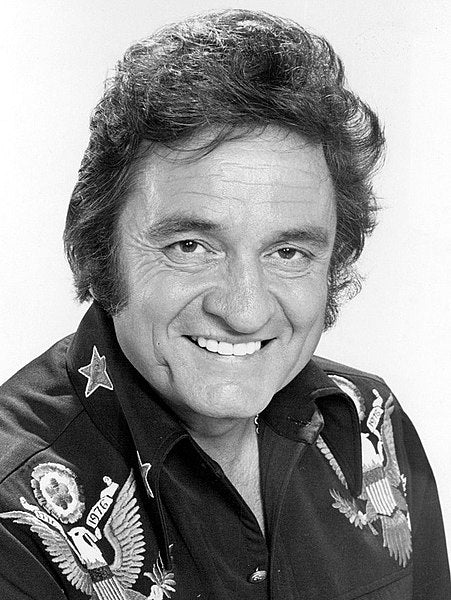

In this issue: Anne E. Johnson riffs on bass great Marcus Miller and one of music’s most legendary figures: Johnny Cash. Tom Gibbs looks at new and reissued music from Rush, Jason Isbell, Dire Straits and Shostakovich. Professor Larry Schenbeck smiles over four Figaros. Roy Hall thinks about smuggling. Dan Schwartz notes the beautiful ordinariness of the band Elbow. John Seetoo continues his series, Songs of Praise from Unlikely Artists.

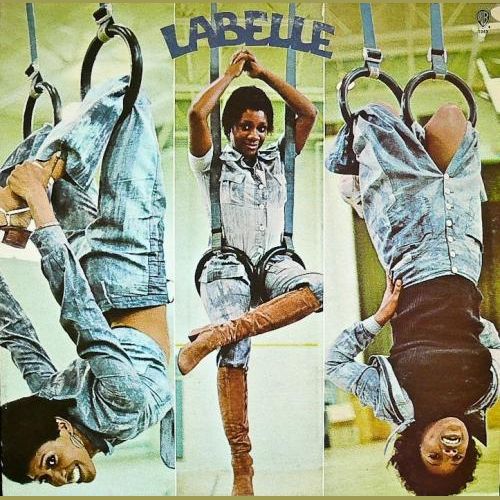

PS Audio has launched a new record label! Octave Records is here. John Seetoo does an interview with mastering maestro Steve Hoffman. Rich Isaacs’ third installment on Italian progressive rock features Sensations’ Fix and Arti & Mestieri. Wayne Robins basks in a Pacific Breeze of Japanese pop. J.I. Agnew concludes his Q & A on vinyl polarity. Jay Jay French realizes it’s never too late to start over. Ken Sander hangs with Labelle. The issue wraps up with cartoonist James Whitworth taking a stand, a tangerine dream and Bonnie bringin’ it.

In this issue: Anne E. Johnson riffs on bass great Marcus Miller and one of music’s most legendary figures: Johnny Cash. Tom Gibbs looks at new and reissued music from Rush, Jason Isbell, Dire Straits and Shostakovich. Professor Larry Schenbeck smiles over four Figaros. Roy Hall thinks about smuggling. Dan Schwartz notes the beautiful ordinariness of the band Elbow. John Seetoo continues his series, Songs of Praise from Unlikely Artists.

PS Audio has launched a new record label! Octave Records is here. John Seetoo does an interview with mastering maestro Steve Hoffman. Rich Isaacs’ third installment on Italian progressive rock features Sensations’ Fix and Arti & Mestieri. Wayne Robins basks in a Pacific Breeze of Japanese pop. J.I. Agnew concludes his Q & A on vinyl polarity. Jay Jay French realizes it’s never too late to start over. Ken Sander hangs with Labelle. The issue wraps up with cartoonist James Whitworth taking a stand, a tangerine dream and Bonnie bringin’ it.

Loading...

Issue 113

Peonies en Regalia

In this issue: Anne E. Johnson riffs on bass great Marcus Miller and one of music’s most legendary figures: Johnny Cash. Tom Gibbs looks at new and reissued music from Rush, Jason Isbell, Dire Straits and Shostakovich. Professor Larry Schenbeck smiles over four Figaros. Roy Hall thinks about smuggling. Dan Schwartz notes the beautiful ordinariness of the band Elbow. John Seetoo continues his series, Songs of Praise from Unlikely Artists.

PS Audio has launched a new record label! Octave Records is here. John Seetoo does an interview with mastering maestro Steve Hoffman. Rich Isaacs’ third installment on Italian progressive rock features Sensations’ Fix and Arti & Mestieri. Wayne Robins basks in a Pacific Breeze of Japanese pop. J.I. Agnew concludes his Q & A on vinyl polarity. Jay Jay French realizes it’s never too late to start over. Ken Sander hangs with Labelle. The issue wraps up with cartoonist James Whitworth taking a stand, a tangerine dream and Bonnie bringin’ it.

In this issue: Anne E. Johnson riffs on bass great Marcus Miller and one of music’s most legendary figures: Johnny Cash. Tom Gibbs looks at new and reissued music from Rush, Jason Isbell, Dire Straits and Shostakovich. Professor Larry Schenbeck smiles over four Figaros. Roy Hall thinks about smuggling. Dan Schwartz notes the beautiful ordinariness of the band Elbow. John Seetoo continues his series, Songs of Praise from Unlikely Artists.

PS Audio has launched a new record label! Octave Records is here. John Seetoo does an interview with mastering maestro Steve Hoffman. Rich Isaacs’ third installment on Italian progressive rock features Sensations’ Fix and Arti & Mestieri. Wayne Robins basks in a Pacific Breeze of Japanese pop. J.I. Agnew concludes his Q & A on vinyl polarity. Jay Jay French realizes it’s never too late to start over. Ken Sander hangs with Labelle. The issue wraps up with cartoonist James Whitworth taking a stand, a tangerine dream and Bonnie bringin’ it.

Introducing Octave Records: Audiophile Sound, Benefiting Musicians

Hope you don’t mind if I put on my proud-family-member hat here, to announce that PS Audio has just launched a new record label, Octave Records. As you might expect, Octave is dedicated to audiophile-quality sound – but the label is also doing something unique in terms of artist compensation.

Octave is covering 100% of all studio, mixing, mastering, production, distribution and marketing expenses – so that artists may directly share in retain sales revenues. The artists will also retain ownership of their music. The label’s intent is to give artists a creative as well as financially supportive environment.

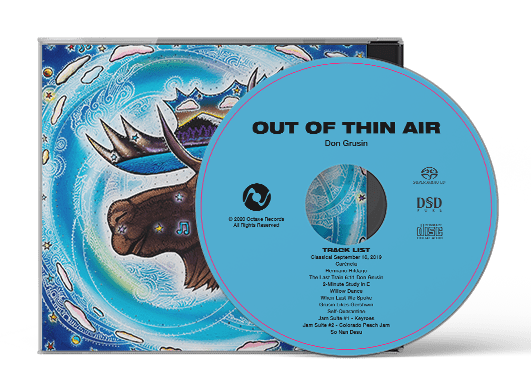

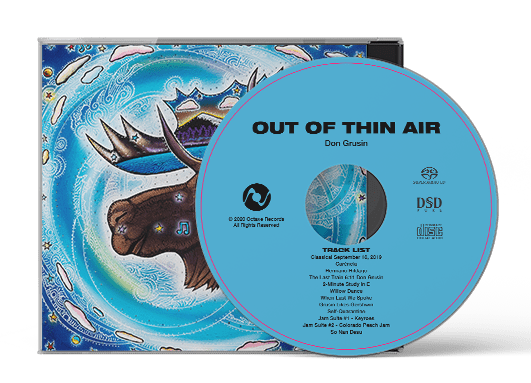

Octave Records’ first release is Out of Thin Air by musician/composer Don Grusin. It’s a jazz-tinged solo piano recording, now available as a limited-edition two-disc set with a DSD pure stereo and multichannel hybrid SACD, plus a DVD data disc containing hi-res stereo 192kHz/24-bit PCM and DSD files.

Gus Skinas is the recording and mastering engineer behind Octave Records and its studio, located in PS Audio’s Boulder, Colorado facility. He’s worked on hundreds of recordings from the Rolling Stones to Nat King Cole. We took the opportunity to talk about the technology and philosophy behind Octave and Gus’ approach to recording, and ask Don Grusin for his thoughts.

Frank Doris: What kind of recording and mastering equipment are you using?

Gus Skinas: We’re using the Sonoma DSD system. One part of it is a recorder, and the other part is a DSD processor. The recorder can be used for up to 32-track recording. We have that hooked to a Studer analog mixing console. If we’re recording here in Boulder we’ll generally go direct into the recorder using Forsell mic preamps, and use the Studer to mix. [If recording on location, Gus takes the Sonoma units with him – Ed.]

The other part of the Sonoma system is a DSD signal processor where you can mix and do dynamic processing, all at the DSD sample rate. I think the important thing is that you stay at that high sample rate and if you do that, the system lets you do all your processing at that [native] rate and it doesn’t sound “digital.” It sounds very authentic and there’s an emotional connection.

The Sonoma recorder sounds, and more importantly it feels like it’s going to analog tape. If we’re going to keep this analog feeling, we have to do pretty much everything in the analog domain (other than the initial DSD recording).

FD: Don, What was the inspiration for Out of Thin Air? How did you go about composing it?

Don Grusin: I wanted to make a statement with our first recording in my new Moose Sound studio. Also, I wanted to explore the acoustics of the studios and work with [Five/Four Productions recording engineer] Robert Friedrich and Gus, super-pro guys.

I’ve always been impressed by my heroes, and wrote a theme for them, “Keyroes,” on the record. My favorite players are Herbie Hancock, Keith Jarrett, Oscar Peterson, Bill Evans, Marian McPartland, Art Tatum, Thelonious Monk, my brother Dave Grusin and maybe most importantly Joe Zawinul if I had to choose one. And then the new guys like Russell Ferrante, Alan Pasqua, Mitch Forman, Eliane Elias, Otmaro Ruiz, Brad Mehldau – there are so many I admire! I’m listening now to Arthur Rubenstein doing all the Chopin catalogue and am newly-amazed at his sense of touch and physical grasp of the piano, a not very forgiving instrument played at that level. FD: What would you call your music – inspired by jazz, life experiences, or something else? DG: After Paul McGowan and Gus Skinas suggested I do this project up here in the mountains, I started thinking and writing, influenced by the beauty of the place. In a couple of cases I drew on music that I had already written or recorded on previous albums; for example, “Carência” and “The Last Train.” For a time I didn’t want to be called a jazz musician but when I was [a young kid] in school, when learning classical, the girls in the class kicked my butt! So I went in a different direction. I’m not a trained musician – I play all street stuff. Inspiration for me comes from so many years traveling to other countries, living in LA and in Mexico, the ocean, and the amazing lineup of music friends I’ve made through music. Also, their friends who run restaurants or gas stations, or radio people, the attorneys, the movie guys – it all adds to a hefty collection of experiences which almost unconsciously guide my playing and composing. It’s like having a world of consultants from every corner and every part of life. FD: Gus, how did you record the Out of Thin Air album? GS: We recorded it at Don’s Moose Sound facility, live to stereo. We also recorded it live to surround for SACD. Robert did the recording and mixing and I did the editing and mastering. Don has a seven and a half-foot Yamaha C7FII grand piano. We used three Sanken CO-100K mics near the piano – very high bandwidth; they go up to 100 kHz. We used a stereo ribbon AEA R88 mic to get the room sound, both for the surround-sound version and we also added some of that into the stereo mix. We ran the Forsell mic preamps into a tiny little SSL SiX console. Live to stereo. It’s the way records should be made. FD: Did you use any compression or plug-ins? GS: We had a compressor inserted in case of overloads, but it never triggered. Our philosophy [at Octave] is that we’re going to be recording pretty much everything using DSD recorders and DSD and analog signal processing. Fairly simple projects in terms of the complexity of the production. We have a small main recording space but we can put the drums out into the warehouse [adjoining the main studio] and get this giant big warehouse sound for the drums. It sounds really great with the natural reverb in the warehouse. We’ll do that on the weekends or evenings when the factory’s not in operation. Mostly when we record here we’ll go through the Forsell or Grace mic preamps straight to the [Sonoma] machine. We try to stay away from compression but if we need it the compressors in the Studer console are very good. I’m monitoring using three PS Audio BHK Mono 300 amplifiers, power conditioners and a DirectStream DAC to monitor the Red Book CD when mastering. In the control room, we are monitoring on ATC-SCM50 loudspeakers, and in the mastering room, we are monitoring on the Sony ES SS-M9ED speakers that go up to 100 kHz. FD: What do you think of the “loudness wars” and all that? GS: I’m not a part of it. We don’t participate in that at all. Pop music…it’s what all the pop mastering engineers are doing. But it’s not as bad as it used to be. If it’s not loud enough, just turn up the volume! I just want it to sound natural. I want it to sound real. And the whole thing with DSD is, it sounds, and more importantly feels authentic. With PCM [digital] you can have something that sounds great, but it doesn’t necessarily feel authentic. There’s something wrong with it, your brain knows that there’s something wrong with it, and it kind of pushes you away a little bit. I believe that the authenticity is directly related to the sample rate. DSD is in the millions. PCM is in the thousands. The common belief is that we can only hear sound between 20Hz and 20kHz. I’m not sure this is correct. I believe we perceive sound much further up even if we can’t hear a tone above 20 kHz. And we definitely perceive [problems] in the timing of things. These might be very small and pretty much unmeasurable but we do perceive them. And it affects the believability of what we hear. I believe these timing problems are greater as the sample rate goes lower. The higher the sample rate, the closer we get to analog. I want to mention something John Hiatt said after we finished recording Master of Disaster. An interviewer asked him, “why do you go through the trouble to record to this new technology when you could just run Pro Tools and be done with it?” [Pro Tools is an industry-standard computer recording program – Ed.] Hiatt replied, “what the ear hears, the heart must believe.” To me, that’s it in a nutshell! FD: Don, what was it like to record the music? DG: Such great fun. The ears of both Gus and Robert are astounding. They would point out something and describe what they heard, and only then in some cases could I “hear” it. I’ve recorded with many giant engineers including Roger Nichols and Don Murray, but this one was a new experience for me. And to [be able to] play freely, enabled me to get “out of body and mind” at times and just let the essential “artist” part of me come through. It’s a feeling I really like and it doesn’t always happen that way. FD: Gus, for future releases are you going to stick to this kind of live-in-the-studio, minimalist kind of recording concept or are you open to, say a Steely Dan kind of big production thing? GS: We’re not doing heavily processed and produced projects. It’ll be pretty much simple recordings of small bands, duos, trios, maybe some jazz quartets, stuff like that. Good musicians and very simple micing and recording to DSD. We want to keep that believability thing in everything we do.

A view from the Yamaha C7FII piano.

A view from the Yamaha C7FII piano. A view from the Moose Studios control room.

A view from the Moose Studios control room.

Vinyl and Absolute Polarity: Q&A, Part Two

In Part One of this dialog between J.I. Agnew and reader/engineer Bob Lehman (Issue 112), they delved into the technical aspects of vinyl record manufacturing and absolute polarity. The dialog continues here. It’s longer than our usual article length, but the complexity of the subject requires going into detail – including addressing Einstein’s theory of relativity!

Bob Lehman: So, are these transducers [microphones, tape recorder heads, phono cartridges and disk cutter heads] in some way responding to the derivative of the air pressure, magnetic field, or physical displacement phenomena?

J. I. Agnew: For tape heads, e = N(dφ/dt). For phono cartridges, e = ds/dt, but internally this just translates to e = N(dφ/dt), since any displacement of the stylus causes the magnet or coil to move relative to each other, thereby changing the flux linking the coil turns, which generates an EMF (electromotive force or signal voltage) whose magnitude depends on the number of turns (N) of the coil and the flux swing (this applies the same way to moving magnet and moving coil cartridges, with slight variations for moving iron cartridges but it can be considered equivalent).

BL: If true, would it really matter in any practical way, since, with the possible exception of the case of [a DC signal], under the principle of the Fourier theorem/series, any complex waveform can be expressed as the sum of the integral pure sine wave multiples of its fundamental frequency?

JIA: Both in mathematical terms (a Fourier transform) and in practical measurable/audible terms, although the frequency range of interest may be adequately covered (down to 10 Hz or so for vinyl records), the fact that the system response does not extend down to DC will cause issues with the phase response. In a mathematical Fourier transform, a complex wave is “transformed” into multiple sine waves, one for each frequency component of the original complex wave, each at a certain amplitude and with strictly defined phase relationships between them. If we attempt to reconstruct the original complex wave from these sine waves, at the correct amplitudes, but with altered phase relationships, the result would be a different waveform!

Errors at subsonic frequencies, such as 10 Hz, can cause phase anomalies well into the audible range, greatly reducing the system resolution and the realism in the low frequency range. It is worth remembering that the lowest C note produced by a 32-foot organ pipe has a fundamental frequency of 16.351 Hz and the low A on a piano has a fundamental frequency of 27.5 Hz.

BL: If the [above] assumptions are true, is that taken into account in any way in the design of the related mechanical, electrical and magnetic equipment? [Conversely], a DC signal applied to a DC-coupled electromagnetic loudspeaker can and will push the diaphragm in one direction and it will stay there, and if the listening room is 100% air-tight, a constant air pressure increase or decrease will be produced in it. Ah, yes, finally, we get to the connection of these questions to absolute polarity! I assume that a totally DC-coupled electrostatic loudspeaker would do the same thing, but I don’t believe that any exist, as most are transformer-coupled to the driving amplifier. Electrostatic headphones do of course exist, and are often directly driven by solid-state or tube drivers without coupling transformers, so I’m guessing that they could produce a constant diaphragm displacement if driven by a DC signal, if they are still otherwise fully direct-coupled.

JIA.: Most transducers and electronics used in sound recording and reproduction are designed to have cut-off frequencies low enough as to be effectively insignificant. A 0.5 Hz cut-off frequency on a microphone preamplifier is low enough to not affect frequency or phase in the audible range. The 10 Hz mass/compliance resonance of the tonearm and cartridge is not as low as would be ideal for perfect phase response, but is essential to filter out unwanted sounds and is well manageable with good design, to the extent of being almost insignificant on its own. It does become significant, however, as soon as someone carelessly designs a second 10 Hz cut-off into an amplifier or preamp. Anything intended for use with a turntable must have its cut-off at a much lower frequency.

The worst offenders are usually the loudspeakers, which very rarely do much below 30 Hz, with most low-cost bookshelf speakers having cut-off frequencies as high as 80 – 100 Hz! Needless to say, with such loudspeakers, any effects from the 10 Hz cut-off of the turntable would be entirely masked.

Loudspeakers with responses extending below 20 Hz and very respectable phase responses do exist, and they tend to be large and expensive. They are, however, absolutely essential in professional mastering facilities, where low-frequency phase error effects must be clearly audible to be adequately dealt with. In the current state of the industry, with minimal recording budgets and only a small percentage of the audience in possession of big loudspeakers that can actually reproduce low frequencies, very few recording and mastering facilities are actually equipped with proper monitoring facilities. This is not just limited to equipment design, but also studio design and the mentalities prevalent in the recording industry. The gap between good sound and horrible sound is widening!

Regarding DC pressurization, following on from the discussion in a previous question, while it could be theoretically possible, it would not necessarily be unconditionally beneficial to the listening experience. From an absolute performance standpoint, the electronics would probably all benefit from a response down to DC. Most transducers would not, as the microphones then would be acting more as barometers, given that the static atmospheric pressure due to gravity is much greater than the small modulations of air pressure that we perceive as sound. The cartridges would then act as displacement sensors, tape heads would act as compasses, and so on. It would be difficult to exclude the “environment” information, but otherwise keep the response to DC, to ensure a perfect phase response. There are much more practical ways of preserving a good phase response without needing everything to work down to DC, such as by careful design of cut-off points in transducers and by considering the entire recording and reproducing chain as one system, in which each individual component must work in harmony with all other components.

BL: What about a tape head and recording tape if everything is direct coupled (theoretically, even if not usually implemented that way). If presented with a DC signal, would the tape head create, and would the tape record, a constant magnetic field?

JIA: Tape itself is just ferromagnetic particles (on a substrate). In the presence of a permanent magnetic field, tape will become permanently magnetized (DC magnetization). This could even be done without a tape machine, just by bringing a permanent magnet close to the tape. It can also be done with an electromagnet, with or without a tape machine. The recording head is essentially an elaborate electromagnet, mounted to a tape machine. Recording DC magnetization onto tape is as simple as hooking up a battery to the recording head with the tape running (or even stationery, which would just magnetize the part of the tape in front of the head). DC-coupled recording electronics will achieve the same. It is simple to record DC to tape, but it cannot be played back with Faraday-principle repro heads. Such a tape recording could be played back with Hall-effect devices, but to no sonic benefit. In fact, most probably to great sonic detriment.

BL: And the same question [about presenting DC signals to] a disc cutter lathe – again, if 100-percent direct-coupled (even if in practice things aren’t usually implemented that way), would the cutter produce a “constant” displacement cut in the lacquer disc? (Aha, yes, your comments about viewing the cut disc with a microscope were what triggered these questions, at least at this time – I’ve wondered about them for a long time, since learning in college that the output of a coil in the presence of a magnetic field (e.g., a phono cartridge) is a function of the first derivative of the magnetic field, as opposed to all of the electronic components in the signal chain.

JIA: There are in fact examples of fully DC-coupled disk recording lathes, where even the cutter head was mechanically DC-coupled to the disk. A direct current to the drive coils would increase the depth of cut. Therefore, such a system could produce a constant amplitude (constant displacement) cut from DC up until you fry the coils at some high frequency as a result of gross thermal overload while trying to accelerate the cutting stylus to the velocity of light!

This is a pretty hard boundary, since even if we could create a cutter head which would not suffer from thermal overload at extreme velocities, as the cutting stylus would approach the velocity of light, it would suffer a relativistic mass increase (as per Albert Einstein’s paper, titled “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies” published in 1905) which would most probably result in somewhat reduced output from the head, assuming that force and acceleration are not limited. (Note: Disregarding the fact that such velocities could never be accurately represented on 33-1/3 or 45rpm 12-inch records, electromagnetic induction effects only remain dominant while the velocity is much less than that of light. If the moving system of a phono cartridge would be made to approach the velocity of light, displacement current effects would need to be considered and very strange things would probably happen. Do not try this at home!)

Either that or the cutting stylus would travel in time, which might cause minor glitches in the time response of the system (or a gap in the time-space continuum).

BL: Again, if any of this matters, is it taken into consideration in the design of the related recording and/or playback equipment?

JIA: Playback turntables are never DC-coupled to the disk due to the existence of a tonearm (this applies the same to pivoted and tangential arms). But a lot of research went into where to place the mass/compliance resonance of the system, for the least amount of audible side effects.

Compared to turntables, there were very few manufacturers of disk recording lathes and only three or four types of cutter head suspension designs. The early ones were actually DC-coupled to the disk and had an excellent phase response, but were not easy to control for groove depth using the disk-cutting automation systems of the time. As market forces came to value longer playing duration per side much more than phase integrity, and at a time when very few loudspeakers offering decent low-frequency phase response existed, most of the industry moved to floating cutter head suspensions, where groove depth could be automatically controlled, along with the pitch, to assist with fitting more music onto a record side.

Not only would the buying public get more minutes per side for their money, but they could also have it cheaper! The most popular disk mastering lathes became the ones that were offering automation that allowed a far less experienced operator (read: someone who could be paid much less and be easily replaceable) to cut records, without accidentally destroying the incredibly expensive equipment involved and with a low disk-rejection ratio as well. The machines themselves were no longer designed for best sound, but to best benefit business. Everyone was happy – apart from those who cared about sound quality.

Today, 35 years after the commercial mass-manufacturing of disk mastering lathes ceased, the surviving systems in active use are all heavily modified with custom parts, a bit like hot rods! Some rebuilders went for maximum automation, others aimed for lowest cost, and a few went for ultimate sound quality. In this last category, all of the aforementioned issues are taken into consideration and improved parts are custom-made as one-off items, at considerable expense. This is a micro-world of its own; no major manufacturers want anything to do with this, as by now this kind of specialization relies entirely on a very few remaining, highly skilled and entirely irreplaceable individuals, complicated and time-consuming precision machining operations (which often cannot be automated) and a very small but rabidly dedicated niche market.

BL: Does the RIAA curve take any of this into account, or is that purely to manage the practicality of which frequencies can be cut at which amplitudes without overheating the cutting head, eating up too much groove spacing or causing too much pre- or post-echo, [along with] introducing too much noise, causing the playback stylus to jump out of the groove, [and so on]? Or might the recording and playback processes normally be complementary in some way [from a mathematical standpoint] such that, if derivatives are involved, an integration somewhere complements a derivative elsewhere?

The RIAA curve. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The RIAA curve. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

JIA: The RIAA curve only serves to reduce the space requirements the record groove would take up at low frequencies and to improve signal-to-noise ratios at high frequencies. (In other words, the ratio of the intentional amplitude of playback stylus excursion due to groove modulation, versus the unintentional playback stylus excursions while tracing the molecular structure of the disk record material).

The RIAA pre-emphasis causes phase shift at the time of recording and the RIAA de-emphasis causes the exact opposite phase shift. The phase shifts cancel each other out and restore the original relative phase relationship. That said, the mathematical differentiation and integration (pre-emphasis and de-emphasis) are indeed complementary, but are entirely due to electronic circuitry, implementing the RIAA time constants, and are unrelated to the derivatives discussed as pertaining to transducers.

BL: When looking at a stereo disc from the front of the playback equipment (i.e., at the front of the phono cartridge), which of the two groove walls correspond to the left and right channels? You alluded to this in discussing that the cutting lathe microscope can be looking in one or the other direction, thereby possibly reversing the groove sides from what one might assume, but you didn’t define which channels are on which side from either orientation.

JIA: Looking at the front of the playback cartridge (not the wiring side), the left channel is towards the spindle, on the left groove wall, and the right channel is towards the edge, on the right groove wall.

BL: Despite the various existing standards that you cited [in Part One of this article], and the many variances [in these standards], are you in effect saying that, yes, absolute phase differences can be heard, at least under some conditions, but given the typical multiple microphones of different types and the plethora of other equipment used to make almost every recording, and [when you factor] in the disc (or tape) manufacturing chain and the playback equipment chain, there’s “practically” no hope of ever achieving any absolute phase consistency?

JIA: On the contrary, it is not actually that difficult to maintain phase consistency and absolute polarity, when working sensibly and with properly engineered equipment. But it is necessary to verify the operation of all equipment to be used in a professional audio facility and to keep it all properly calibrated and interconnected. Home systems are much simpler and the availability of products by manufacturers known for their high standard of engineering certainly helps.

BL: And even if there was a completely and rigidly controlled environment for the aforementioned variables, wouldn’t the different microphone distances from different instruments alter absolute polarity anyway, with either the popular “multi-track mono and mixer panning” approach used for most recording or perhaps even the minimalist two- or three-mic “natural” approach that is used for some elite audiophile recordings? (The highly-desired natural stereo imaging for the latter “natural” approach with real-time acoustic music depends mostly on the relative phase differences between the mics as they “hear” the different instruments, vocalists, room/hall ambience, etc., whereas the other approach depends largely on amplitude differences between the stereo channels via the multi-channel mixer pan pots.)

JIA: First and foremost, for a recording engineer to be able to assess the effects of microphone selection and positioning, to decide which technique would best convey the sound to the recording medium, a completely and rigidly controlled environment is an absolute requirement. If the room acoustics and the monitoring system in the studio do not provide adequate resolution of detail, everything else is totally up to good luck. There is no way for an engineer to measure or guess what the monitoring environment does not reveal. Especially when the target audience would be audiophiles with exceptional systems, the studio environment would need to be much more detailed and more revealing than any of the audiophile systems that the record would subsequently be enjoyed on. The engineer, in this case, would also need to have some experience listening to exceptional audiophile systems, to be able to fully appreciate how high the expectations can be.

As for microphone distances, they do affect what is captured, in terms of frequency/phase response, dynamics, reverberation, and stereophonic imaging, so their positioning and careful selection is critical.

Microphones do not only capture the sound from an instrument or ensemble, but also the sound of the room. Changing the position of the microphones or performers by even a few centimeters can make a huge difference.

Using the example of sitting in a concert hall, the sound of the instruments nearest to our ears arrives earlier than the sound of the instruments further away. This adds a sense of depth to the “soundstage” and enhances the sense of width, both in real life and in a reproduced recording. However, in all performance spaces, there are always seats that offer a better overall auditory experience than others. In positioning the microphones for a recording, the intention is usually to find the “best seat” and capture this experience.

When a coincident or spaced pair of microphones (or three as in the technique employed by Decca) are used, the intended absolute polarity is the one that the engineer or producer decided upon as offering the best representation of the performance, through the position of the microphones. It does not necessarily mean that all instruments will always produce an outwards loudspeaker cone motion for a positive pressure increase in front of the instrument! This is irrelevant, since the performance is not enjoyed by placing your head in front of a trombone and a violin at the same time! What matters in this case is the pressure decrease/increase in the hall, where the microphones are positioned.

This should then reproduce, on your system, something resembling what the engineer and producer heard when making the recording, which was presumably intended to sound as close as possible to what they heard in the performance space, prior to setting up any microphones. In multiple-microphone recordings, inaccurate positioning of the microphones relative to each other causes extreme phase cancellations, a confused, unstable stereophonic image and unnatural-sounding instruments. Microphones also need to be very carefully positioned with multi-miked recordings, but the approach is a bit different, since the multiple-microphone approach usually aims to create an experience that was not necessarily there to begin with, instead of just capturing what was there. This can be beneficial in cases where the original performance space’s acoustics are problematic, but when everything is as it should be in the hall, I personally prefer just a pair of microphones.

In rock and pop music, however, additional microphones are sometimes used for effect, to present a larger-than-life soundstage and enhance rhythmic impact. In such cases, the polarity of an individual microphone could be intentionally inverted to create the desired effect. Since this is done to create an artificial reality that was never really there, the “correct” absolute polarity is again whatever the producer intended, provided that it was possible to properly hear the result while the recording was being monitored in the studio.

If we all had exactly the same living room (and drove identical cars) with exactly the same loudspeakers in them, in exactly the same position, then we could probably skip the studio environment and just work on recordings in any living room, since we would hear exactly the same result that everyone else would also hear in their own living room.

If, in such a world, we wouldn’t have gotten arrested by the secret police and if music wouldn’t have been forbidden, along with reading, thinking, or defecting to the other side, where the sheer diversity in living rooms and loudspeakers would necessitate completely and rigidly controlled environments in which recordings were to be monitored. No need to prohibit reading, thinking or defecting. Market trends would have pretty much rendered the first two obsolete. As for the third, where would you go to? Perhaps this is why space colony concepts were popular with multi-millionaires, although recent global events may make them unpopular again, and hopefully steer things in a different direction, before we all end up having the exact same living room in space!

Header image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Evan-Amos.

The Beautiful Ordinariness of Elbow, Part One

Throw those windows wide

One day like this a year would set me right.

…from “One Day Like This”

In ye olden days of 30 years ago, as a writer I would struggle to try to describe music. This was always a thankless task; imagine trying to describe the sheets and clouds of pure sound that comprised György Ligeti’s best work.

But a virtue, as well as a massive liability, of the modern age is YouTube. And YouTube makes this job much easier. I’m talking about attempting to describe the music of Elbow, an approximately 20-year-old band from Manchester, England. Vaguely like Radiohead or Coldplay (as if they’re similar), but not quite – although they manifest a similar melodicism.

Let me begin by sharing the track in which I “discovered” them:

I heard this track on a pretty lousy station while driving in Los Angeles, while channel hopping, and I was fairly riveted. I pulled over to listen and waited to find out who they were – I was that enthralled. It had been years since I had found a band that I liked that much.

Although we have a few friends in common, as they’re from Manchester, what I know about them I’ve mostly found out online, like from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elbow_(band).

There’s this, a playlist of an in-studio gig with an orchestra at Abbey Road that blows my proverbial socks off:

httpv://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLE8D1D0EBE3C89387

And there’s this live show:

As to whether they’re good musicians or not, they’re certainly good enough to play their music – there’s nothing dazzling here, except the band itself. And who writes it? I’m not going to find out – I’m deliberately keeping it mysterious.

It occurred to me while listening to a few concerts of theirs that are on the YouTubes that in weird ways they remind me of late 1970s Genesis, and Talking Heads at the beginning of the 1980s (and those bands were nothing alike). They’re like Genesis in that, once Peter Gabriel left the band and they turned in a decidedly pop direction, one could sense that they could really play, but quite often they simply didn’t, and left it to the music or to the song to speak for itself (E.G. “Entangled*”, from A Trick of the Tail) – which is a hallmark of maturity, not having to always show “your stuff.” And Elbow demonstrates this maturity even on their early albums, though much more so on the ones from 2008’s The Seldom Seen Kid onwards. But: they also remind me of Talking Heads, circa their (and Brian Eno’s) shockingly brilliant Remain in Light, in that the music is made up of broken-down modules of repeating figures – which sounds real pointy-headed when I write about it, but it’s what I mean.

(*Okay, this is weird. I just found an online radio show and interview, in which singer Guy Garvey says that the one Genesis song that everybody in the band agrees that they like is “Entangled.”)

If you have Roon, you’ll find more contemporary comparisons in their descriptions of the band – to Coldplay, and Talk Talk, and Supertramp, and Superchunk. But this is on their early albums, which were…more conventional? I don’t hear Elbow as a radical band – in fact they’re comfortably un-radical. Their early albums were a bit more conventional (and yes, they have gotten more Elbow-ish in their self-defined sense). The rhythms and arrangements are more spacious and fragmented, and their anthemic-quality has gotten bigger and more ambitious. They’ve evolved from a great worn jacket to a massive comfortable sweater. (As I struggle to describe the music, I take some comfort in the writers that Roon takes their stuff from having just as difficult a time.) Comfortable, familiar music and vocals – that nonetheless are unique and new. And vocalist Guy Garvey has a rough/smooth delivery that’s very comforting and familiar.

If I find any fault with their early albums (which I sometimes do), it’s that the tunes sort of shout “art-rock” without transcending the form, as their later work does – the band has definitely grown as writers/arrangers. (Of course, that’s my taste; you might feel differently.)

In any event, in Part Two, witness me struggle to again describe the indescribable.

Header image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Evita wiki.

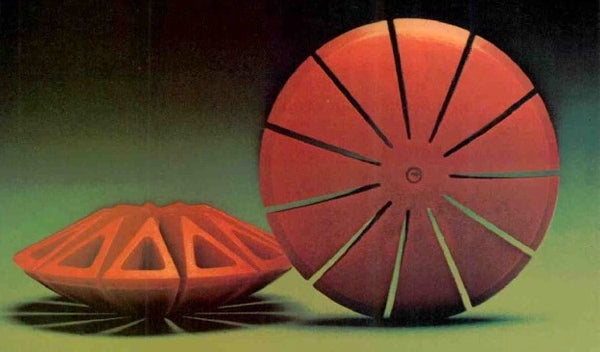

Tangerine Dream

We don't know if this produced uncolored sound or not. From the Museum of the Hard to Believe...er, Audio, October 1977.

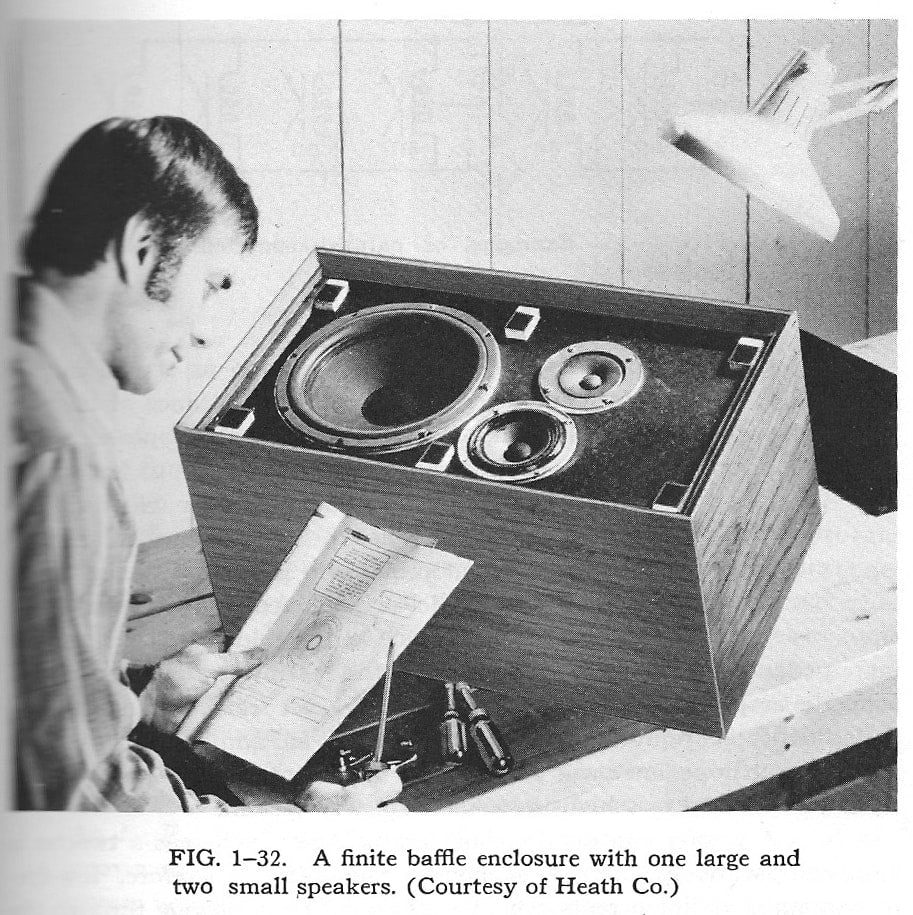

That's one small and two large speakers. Got it? From the MIT Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science...er, Audio Systems, 1974.

Even her bridge club wants to listen! From the Male Chauvinist Hall of Fame...er, Audio, July 1964.

Created by an engineer named Louis W. Erath, a geophysical engineer (seriously), it seems the bass from these was pretty impressive. From Audio, July 1969.

Songs of Praise from Unlikely Artists, Part Two

In Part One of this series (Issue 112), I noted that throughout the history of American music, the influence of the Christian church has been well documented and apparent. While some bands have been working in the Christian music genre from the beginning of their careers, others haven’t been as overt, yet have written and recorded Christian-faith songs – and you might be surprised at who some of them are. Yet, as mentioned in last issue, truth can often be stranger than fiction, and the following stories prove it:

The Byrds

The Byrds repeatedly released songs of Christian faith throughout the band’s 1964 – 1973 lifespan. Ironically, none of the band members at the time was a Christian until the band’s final years, although that would change after the band’s demise. Unlike other musicians in this series, the Byrds, and Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman in particular, have chosen to be interpreters of praise songs, rather than composers.

The Byrds’ electrified version of folk music, mixing electric 12-string guitar, three-part vocal harmonies and Beatles-type arrangements, became the foundation for folk rock.

In 1965, hot on the heels of their breakout hit single “Mr. Tambourine Man,” the Byrds released their follow up, an electrified version of the Pete Seeger folk song, “Turn! Turn! Turn!.” Based on the Old Testament Book of Ecclesiastes, the song contained an anti-war message that resonated during those early days of the Vietnam War. Ironically, McGuinn at the time was becoming an adherent of Subud, an obscure Indonesian religious sect.

The Byrds then borrowed The Louvin Brothers’ “I Like the Christian Life” for their 1968 album Sweethearts of the Rodeo. The first country-rock record, Sweethearts introduced the trailblazing Gram Parsons to the rock music world and became a template for Poco, The Eagles and many others to follow.

The following year, The Byrds recorded a rocking cover version of the Arthur Reid Reynolds gospel song, “Jesus Is Just Alright,” which became a concert favorite, featuring fierce four-part vocals arranged by drummer Gene Parsons and searing electric leads by virtuoso guitarist Clarence White.

McGuinn became a converted Evangelical Christian in 1978 and has continued as a solo artist since then, apart from a 1979 Byrds semi-reunion with McGuinn, Clark, Hillman which yielded a hit song, “Don’t You Write Her Off.”

Bassist Chris Hillman, a co-founder of the Byrds, became more and more integral to the band as time went on, contributing vocals after Gene Clark departed and eventually contributing songs such as “Time Between” and co-writing “So You Want to Be a Rock and Roll Star” with McGuinn. Hillman and Gram Parsons bonded over their shared love of country music and left the Byrds after the Sweetheart album to form The Flying Burrito Brothers.

Hillman cites Nashville pedal steel guitar whiz Al Perkins as the one who led him to becoming a Christian while the two played together with Stephen Stills’ Manassas band during the 1970s. Hillman’s wife of 41 years, former record executive Connie Pappas, influenced his decision to convert to Orthodox Christianity in 1997.

For the most part, Hillman has also chosen to be an interpreter of faith songs more than a composer. One exception is “I’m Still Alive” from Like A Hurricane (1998), where he sings the lines, “I will go on forever, and forever I’ll be in God’s grace through all eternity.”

Hot Tuna/Jefferson Airplane

As a fingerpicking acoustic blues guitarist par excellence and psychedelic rock electric guitar maverick innovator, Jorma Kaukonen has created an impressive body of work over the past 55 years, from “Somebody to Love,” “Volunteers” and “White Rabbit” with the Airplane to a range of acoustic and electric works with Hot Tuna and as a solo artist who encompasses everything from blues, ragtime, folk and country to acid rock and heavy metal. The marathon six-hour Hot Tuna shows of the 1970s cemented a rabidly loyal international fan base that never tires of listening to Kaukonen’s guitar stylings, counterpointed by the awesome Jack Casady on bass.

One of the accomplishments of which Kaukonen is most proud is his exposing the music of the late Rev. Gary Davis to a wider audience. A blind Baptist minister who held church services in a Harlem storefront, Davis played guitar to accompany his congregation, and he perfected a complex ragtime Piedmont blues fingerpicking style that combined contrapuntal elements of Jelly Roll Morton’s piano style with gospel and folk blues.

As a result, over a half dozen popular Davis gospel hymns have become beloved Hot Tuna concert staples, among them: “I Am the Light of This World,” “I’ll Be All Right,” “Oh Lord, Search My Heart” and “Death Don’t Have No Mercy.”

Kaukonen has also drawn upon other songs from the gospel blues and old time bluegrass music canon, including the following:

- “True Religion,” which was written by the Rev. Robert Wilkins, who also wrote “Prodigal Son,” which was recorded by The Rolling Stones

- “Suffer Little Children to Come unto Me” by Woody Guthrie

- “Will There Be Any Stars in My Crown?” by Ferlin Husky

- “What Are They Doing in Heaven Today?” by Washington Phillips

Although he is Jewish, Kaukonen nonetheless felt sufficiently inspired to come up with his own song of Christian spiritual awakening: “I See the Light.” Originally recorded on Hot Tuna’s The Phosphorescent Rat (1974), “I See the Light” contains the quintessential Hot Tuna musical elements: fingerpicked verses and interludes, interspersed with power chords and distorted and highly melodic bass.

“Good Shepherd,” from the Jefferson Airplane’s Volunteers (1969) has an interesting history. Kaukonen adapted the gospel blues song “Blood Stained Banders” by Jimmie Strothers, which was itself a drastically altered version of the early 1800’s Methodist hymn, “Let Thy Kingdom, Blessed Savior.”

According to an interview published in The Poughkeepsie Journal, “Kaukonen was offering the view that the ‘blood-stained banders’ of the lyric was an allusion to the Ku Klux Klan. He continued to find meaning in performing “Good Shepherd” and other songs like it that celebrated religion in one context or another without preaching, saying such material gave him a doorway into scripture: “I guess you could say I loved the Bible without even knowing it. The spiritual message is always uplifting – it’s a good thing.”

Eric Clapton

One of the most famous rock star virtuosos on the planet, Eric Clapton has publicly shared the saint/sinner struggle throughout his life. He has scored numerous artistic and humanitarian triumphs. He has also suffered deep personal tragedies and fought personal demons as well, all the while creating music for millions of fans that connects emotionally, and oftentimes, spiritually.

A long devotee of the blues, Clapton’s obsession with the tormented Robert Johnson, a Paganini-like Delta blues slide guitar master rumored to have “sold his soul to the Devil,” formed the foundation of much of his approach to music. The themes of personal longing and combating one’s inner turmoil have always been a part of Clapton’s expressive guitar playing, songwriting, and singing.

As early as 1969 Clapton first became a Christian and wrote the song, “Presence of the Lord,” which was featured on Blind Faith (the album from the band of the same name). Although he chose to have Steve Winwood sing the studio version, Clapton would later sing it himself with Derek and the Dominos and as a solo artist in concert. It is reputedly the first song which Clapton wrote completely on his own.

As he went through bouts of heroin addiction and alcoholism through the next decade, Eric Clapton’s love triangle angst with his best friend George Harrison and Harrison’s then-wife Pattie Boyd fueled the creation of his masterpiece, Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs (1970).

During that time, Clapton would repeatedly return to songs of praise and faith, composing gospel blues songs like “Give Me Strength” from 461 Ocean Boulevard (1974), featuring Clapton playing dobro and singing the refrain, “Dear Lord, give me strength to carry on.”

Always mindful of his musical roots, Clapton included the blues gospel hymn covers, Blind Willie Johnson’s “We’ve Been Told (Jesus Coming Soon)” as well as “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” on There’s One in Every Crowd (1975).

Clint Eastwood-esque western movie imagery juxtaposed with an itinerant musician lifestyle is the setting for “Hold Me Lord,” which he wrote for Another Ticket (1981).

Finding sobriety and emotional stability in the 1980s, Clapton participated in the 1985 Live Aid concert and began exploring different musical terrains outside of his blues and R&B post-Dominos bands of the 1970s. Branching out to work with Phil Collins, Nathan East, Russ Titelman, Stephen Bishop, Jerry Williams, Greg Phillinganes, and covering songs from artists as diverse as Japanese synth pop stars Yellow Magic Orchestra, Eric Clapton still would include songs like “Holy Mother” from August (1986). This plea for spiritual and emotional comfort even led to a duet with famed opera tenor Luciano Pavarotti.

The tragic death of his four year old son, Conor, prompted Clapton’s mournful ballad, “Tears in Heaven,” which became his biggest selling single and won multiple Grammy awards in 1993, including Song of the Year and Record of the Year. He would stop performing the song in 2004.

In 1998, Eric Clapton established his Crossroads Centre in Antigua for substance abuse treatment and would gather famous guitarists from across the spectrum to participate in annual concert fundraisers.

Blake Shelton

Unlike many of the other musicians in this list who have had to deal with substance abuse or alcohol, Blake Shelton has pretty much lived up to his clean-cut image, which has helped to propel him to country music superstardom, a national TV gig on The Voice, and a loving relationship with rock songstress Gwen Stefani, about which tabloids struggle in vain to find dirt to write about.

However, Shelton despaired over his crumbling marriage to country spitfire Miranda Lambert in 2015 and has said in interviews that God spoke words of comfort and hope to him in a dream. As he awoke, the first four lines of a song that would become his 2017 hit single, “Savior’s Shadow” were already an ingrained earworm that Shelton hummed repeatedly, replete with a message of inspiration that “God is with us” in the refrain:

Though the devil try to break me

My sweet Jesus won’t forsake me

When I’m in my Savior’s shadow

Where I’m supposed to be

“Savior’s Shadow” was the second single release from If I’m Honest (2016). Shelton purposely released the song to spread the message of hope through Christ, not necessarily to become a hit, and his black and white music video was soberly understated compared to the happy-go-lucky playfulness of his other videos and mega hits like, “Honey Bee” or “Doin’ What She Likes.” Nevertheless, “Savior’s Shadow” managed to reach #14 on Billboard’s Christian Music charts and broke the Top 50 on the Country charts.

Prince

When the world lost the musical genius that was Prince in 2016, practically every single article and news clip referenced his hit songs, like “Purple Rain,” “Kiss,” “When Doves Cry,” “Little Red Corvette” and “others.” His lyrics and performances were chock full of double entendres and risqué allusions, harkening back to blues artists like Tampa Red. He projected an image of sexual obsession throughout his songs and public persona.

However, the hits comprise only a small part of Prince’s musical output, which is allegedly filled with up to 10 more years’ worth of unreleased material still in his vaults. Of the prodigious number of recordings currently available, there are musical clues to a much deeper person than the public persona may have suggested, and which became publicized after his death: Prince was, in fact, a zealous Jehovah’s Witness.

Prince’s own sinner/saint walk showed clues in some of his earlier songs, such as “The Cross” from Sign O’ The Times (1987):

Black day, stormy night

No love, no hope in sight

Don’t cry for he is coming

Don’t die without knowing the cross

Prince later would change “the cross” to “the Christ” in performance following his conversion to Jehovah’s Witnesses in the late 1990s.

While Prince was an extraordinary guitarist, keyboardist, and drummer, he also played excellent bass, inspired by R&B from Motown, Parliament/Funkadelic, Stax/Volt, and Sly and the Family Stone. When he befriended bass icon Larry Graham, who created the funk bass style of slapping, Prince not only approached him for musical collaboration but also for Bible study religious instruction in the Jehovah’s Witnesses faith. The mentor-student relationship deepened throughout the 1990s, with Graham relocating his family from Jamaica to Minneapolis, and with Prince attending Kingdom Hall services.

“The Holy River” from 1995’s Emancipation reflects on the spiritual awakening that Prince was undergoing during this period.

Prince’s The Rainbow Children (2001) album delved deeply into Jehovah’s WItnesses teachings and his “Lion of Judah” from Planet Earth (2007) referenced end times as recorded in the Book of Revelations:

Like the Lion of Judah (Judah)

I strike my enemies down

As my God is living

Surely the trumpet will sound

As the Prince estate releases more recordings from its archive vaults, there will likely be much more to follow.

Part Three, the conclusion of this series will appear in Issue 114.

Header image of Eric Clapton courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Majvdl, cropped to fit format.

Steve Hoffman – Mastering Legend and Audio Restoration Magician

If you have listened to any popular music from the last 75 years or so that was remastered for CD, DSD, SACD or limited-edition vinyl, there are very good odds that you have heard the work of mastering engineer and audio restoration expert Steve Hoffman.

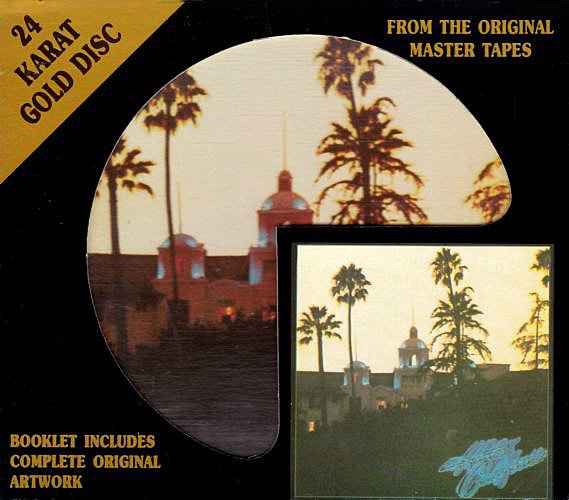

Steve has remastered and restored thousands of classic records from artists as diverse as Ray Charles, Frank Sinatra, The Eagles, Chicago, Sonny Rollins, Muddy Waters, Buddy Holly, Bob Marley, The Beach Boys, Bob Dylan, Rage Against the Machine, Steely Dan, Johnny Cash, Nat King Cole, Earth, Wind and Fire and countless others…the list is staggering in both volume and breadth of musical genres.

Steve Hoffman’s philosophy on remastering is predicated upon a quest to capture what he refers to as the “breath of life”, i.e., to make the artist sound as true to life as possible. Steve’s touch has wowed millions of listeners and has garnered a huge fan base – an anomaly when one considers that the average music listener has no idea what an audio mastering engineer even does. Yet Steve is well-known enough to host an extremely popular forum, (www.stevehoffman.tv), with about 127,000 subscribers.

Such is the magical connection of music. Steve Hoffman’s decisions in the studio have preserved and improved much of the beloved recorded music we own today in our personal libraries, and I think I can speak for every music lover to say that we are all grateful to him for his work.

Copper last spoke with Steve a few years ago (Issues 36 and 37). He discussed some of his past work, his love of vintage tube equipment, his preference for analog tape editing, some of his theories on remastering, and some of the obstacles he had to overcome on the technical, psychological and political fronts.

During this period of COVID-19 lockdown, Copper was fortunate that Steve had some downtime between projects, which allowed him to do this follow-up interview.

John Seetoo: You have lamented that a lot of the recorded sound of contemporary bands is the result of over-compressing the dynamic range, what’s become known as the “loudness wars,” and that the sound is sometimes unduly harsh-sounding due to digital signal processing and a focus on mixing for streaming and headphone listening. As a result, your preference leans much more towards audio restorations of music recorded on classic analog tube equipment. Would you consider new mastering projects but from artists and producers who appreciate and continue to use old-school tube gear and analog tape, such as the Foo Fighters or Tony Visconti?

Steve Hoffman: Of course, but no one wants this type of “old school” mastering any more. It’s not “loud enough.”

JS: As the source material in such a project would be fresh, instead of choosing from multiple versions as you would do with your re-mastering projects of classic material, would your approach in working with the producers and artists differ, if they wanted to make changes after the fact, vs. your standard “do no harm approach?” For example, you dissuaded Ray Charles from wanting to redo his vocal on “Hit the Road Jack.”

SH: I would encourage producers not to squash the dynamics in the original mix, but rather leave that option for mastering so that there would be some dynamic range to work with in going back to the original master tapes. Some producers don’t understand that at all.

JS: The Steve Hoffman “breath of life” philosophy of focusing on making sure that a singer sounds like the actual person or a soloist’s instrument sounds like the real thing and letting the rest of the pieces fall into place is likely a huge part of why you have such a devoted fan base.

Without divulging any trade secrets, how do you approach separation and maintaining realism in duets with vocalists with similar voices, such as when you re-mastered The Righteous Brothers – if you are working off of a mono mix?

SH: Mono, stereo, doesn’t matter, a human person sounds like a human person. You know it when you hear it, right? Well, so do we all. I just make sure that this is something that will work for everything. In mastering I strive to make human voices sound real. It doesn’t matter how many are singing at one time. Unless they are on two different microphones, and then it’s more of a struggle to get them to sound human.

JS: How would you approach that same question regarding the sound of instruments? For example, with a group like The Allman Brothers Band, where Duane Allman and Dickey Betts had similar Gibson Les Paul guitars and Marshall amps?

SH: Nice question. First time I’ve ever been asked this one! I would concentrate on the drums first if I could. Make sure there was something there that sounded “real.” How much of that goosing of course depends on what it’s doing to the rest of the instruments. Strike a fair balance between everything, that’s the ticket. Hard to know when to stop, but it takes practice.

I’ve done just about everything to goose something into sounding better: EQ changes, slight tube compression, adding layers of tube [electronics] in playback to add body to dead-sounding stuff, using different tape machines, feeding the signal back into a big room and adding a bit of the “room” to make it sound more pleasurable, etc. Whatever it takes.

JS: While a mono mix can often be the best source material for a restoration job, have you ever been required to create a stereo master from a mono mix for the sake of a client’s marketing agenda? If so, did you keep it analog or have you deployed digital to achieve acceptable results?

SH:I never have, not once since 1982.

JS: You’ve cited the Beatles’ “She Loves You” as an example of a song with multiple tape edits that used echo to hide the splices. In your re-mastering work, have you ever had to add echo or some other processing to conceal a physical analog edit that wasn’t on the original master?

SH: A few times, usually at the end of a song when it’s cut too close. Listen to Ray Charles’ “What’d I Say” on the two-disk Ray set I did. The last note cuts (chopped off by engineer Tom Dowd). I added reverb to match at the end only, sounds better. Normally I just leave obvious splices, console pops, etc. I like to hear that stuff, it makes me appreciate how much a song is worked on by all concerned. No one else agrees with me on this though!

JS: You have mentioned your close working relationships with people like Ray Charles, Sammy Davis Jr., Ian Anderson and others whose records you have restored. How do you approach re-mastering records where the artists and/or producers have passed away or are unavailable for input feedback? Do you choose a personal favorite recording from that artist’s catalog as a reference?

SH: I never ask artists for feedback. That way lies disaster, trust me. If they like what I do, great, but I never ask for their blessing. Would be pointless.

JS: As a tube gear aficionado, have you been following the explosion of new, boutique manufacturer-designed headphone tube amps? Have you heard anything that could change what has been your negative opinion towards headphones?

SH: I don’t hate headphones; I just wore them for years [when I was] in radio broadcasting and I’m done. Back when I was living at home, I needed good cans so as to not wake my parents. Now, it doesn’t matter, I’m sleeping too! I have a nice Woo Audio (made in New York City) headphone amp and a few pairs of headphones. I enjoy them once in a while, but not for any critical listening. The mix balance on cans throws me way off.

JS: You had a revelatory experience with the small McIntosh tube amps back in the 1990s, but now your website lists Audio Note as your exclusive brand for preamp and power amp use. What is it about Audio Note gear that appeals to you, and what features, if any, are missing that could cause you to switch if you found them in another brand?

SH: I got involved by accident with Audio Note UK. My friend was looking for a turntable and the Audio Note rep brought one over for him to try. We started chatting and I told him I always wanted to hear an Ongaku, ever since the days I saw the circuit in [the now discontinued] Sound Practices magazine. He said he had one and brought it over. That was the start of it. I love single-ended triode [amplifiers], and finding speakers that can move me musically on 10 watts was always the goal. The Audio Note AN-E speakers do that nicely.

That being said, I use the PS Audio PerfectWave transport and DirectStream DAC as my main digital playback system. Works quite well with the Audio Note UK gear.

JS: You are known for trying to keep the signal chain as minimal as possible and will sometimes bypass a console or swap tubes to get a different sound instead of deploying any outboard processing. In your mastering work. Are you using vintage gear like Pultec equalizers and Teletronix LA-2A compressors, or any comparable newer gear when needed? What kind of processing equipment are you currently using?

SH: I use and trust the GML 9500 Mastering EQ unit, my vintage Universal Audio EQ’s and the Teletronix LA-2A when needed (which is seldom). I’ve also used the Sontec MES-432C parametric equalizer. Anything else is just for a needed “trick” or so during mixing, which I do a bit of when I get something old that needs a remix.

JS: Do you use your personal analog Ampex and Otari analog tape machines exclusively, or would you rent a Studer or other unit for playback as needed?

SH: I use my home stuff rarely, mainly to fix splices. When I’m ready to actually master I’ll use a studio that has what I want. Marsh Mastering in Hollywood has the Studer and Ampex machines I like.

JS: For monitoring you use Audio Note and Rogers LS3/5a speakers combined with a Tannoy 15-inch subwoofer. What do you like about this combination, and what steps led to your arriving at it? (According to the website as of Feb. 2020.)

SH: No, I don’t use that combo. The Audio Note stuff is all AN speakers. Another system has vintage McIntosh [and] Marantz [electronics] and my 1968 Tannoy Lancaster speakers. The Rogers LS3/5as I have are used when I need a “dinky” perspective.

JS: You have several different turntable (VPI, Technics) and cartridge (Grado, Shure) systems. Do you often find that vinyl or old acetates are a better audio source for a restoration project rather than tape, or do you only use them when they are the sole existing source?

SH: I haven’t used acetates in years but it is seldom all there is (from the recording tape era). There is always a country that has a dub tape of something. Pre-1949 I’ve used transcription lacquers, etc. for sources but [I haven’t had to do that] for a long time. I use my turntables for listening fun.

JS: If you were re-mastering a recording of an unfamiliar world music genre, like Indonesian gamelan music or Tuvan throat singing, would you approach the project on the fly with your subjective first gut instincts or would you research some other recordings first to get a range perspective on how the instruments and singers can sound?

SH: I would do the research first, yes. Crucial not to go in blind. On the other hand, sometimes ignorance is true bliss because the music is usually transferred with a light hand and that’s always better than some compressed lute with too much air and extra echo to make it sound like you’re listening in the cheap seats…

JS: Have you ever had to compile a single master from several disparate versions with drastically different EQ requirements, due to age and damage rendering each version unusable on its own? In such a case, would you rely on an intact earlier digital transfer, or would you maintain it in the analog realm like the way you re-mastered Jethro Tull’s Aqualung?

SH: It would depend. I’ve had to use many, many “pieced” songs in my years of doing this. Even I can’t remember where the changes are, so I must have done a good job. I would do it digitally if it was really tricky but in the 90’s only analog would do. Now, if it’s going on a 16-bit CD, I’d do it digitally. [If it was being remastered for] SACD, in DSD, and so on. However, if it’s an LP [re-master[, it will remain analog and I’d rather have a slightly damaged section than dump to digital. I mean, what’s the point of that to make an analog record?

JS: Popular music often has a drum beat or other areas where a tape edit can seem relatively seamless. How do you approach edits in classical or jazz music, where the edit points may stand out more glaringly? Would you use echo or other processing when doing a restoration in that instance, or do some kind of cross fade to hide the edit point?

SH.: Well, the trick is to echo the beginning of the edit piece as well. Usually edits can be heard because the original engineer spliced a section without echo but without the echo from the earlier section coming through. Common mistake. I’ll do a backward (tape reversed) echo splotch to get some reverb at the beginning of the splice to match the passage before. Then no one can tell. But editing classical is hard (but not impossible, as 70 years of finely-edited LPs have shown us.) And believe me, there are more edits in our beloved RCA-Victor Living Stereos and Decca/Londons than you could possibly imagine. I once counted over 40 splices in one short Living Stereo passage and I swear I couldn’t hear one of them. Only (by) watching the tape is there a clue. That’s a true pro job!

JS: Have you ever been approached to restore the audio for a film? If so, what challenges and protocol changes did you have to overcome? If not, is there any film in particular that you think could benefit from a Steve Hoffman audio restoration?

SH: Film audio? No, but film music, yes. I worked (moonlighted, actually) at Warner Bros. and helped with score restorations on some of their classic flicks (The Music Man, Gypsy, etc.) Grim work with decomposing stock. Bad for the lungs. Had to quit after a while, couldn’t take the smell any more.

But you’re asking if certain films could use a sonic remix? Sure, but that’s not my area. Would be fun to try though…

JS: In another interview, you cited The Eagles’ Hotel California as a particularly challenging project, due to excessive boominess on the original mix. Do you find that these kinds of issues increased due to the exponential rise of variable-location multi-track recording, and that completed projects in a single studio with a limited track count often led to a better-sounding finished mix? Or do you think it has more to do with the engineer and choice of room for the session in question? Please cite examples, pro or con.

SH: It all comes down to the final mix stage. Sometimes the monitors used cannot show what is actually happening – a good thing in some cases, not so good in others. If there are changes in sound from track to track, I usually leave them for the most part. I think it’s charming. But wild changes of course are disturbing to most and those have to be “fixed” in mastering. Engineers that mix on dinky speakers usually only ever listen on similar speakers. I never mix or master on dinky speakers; they can really throw you off. I could write a book on this subject but I’ll stop here.

JS: The late Dennis Ferrante (John Lennon, Lou Reed, Wynton Marsalis) told me that when he did the remixes for the Elvis Presley CD box set Walk A Mile in My Shoes, he had to go back to the original multi-track tapes because the 4-track mix-downs from RCA were done haphazardly – the stereo balance had a -5dB volume discrepancy, and percussionist Ralph MacDonald’s parts were erroneously muted in the mix-downs.

Would you ever take a project that might require restoring or re-recording an instrument or other parts to a mix before re-mastering, or do you only work with finished mixes?

SH: I guess I could but why would multi-tracks be mixed down to 4? You mean for Quad [quadraphonic sound] or something?? I only know of Columbia [Records] and their weird habit of mixing down 8 channels to 3 and then from that to stereo or mono. The Byrds [recordings] are like that. It’s a pain in the butt because goofs and bad mixing choices are there for all time. Yet, going back to the multi and starting over is also bad; you lose all the charm of the original versions and everything sounds “modern.” I hate those remixes, never listen to them (talking about YOU, Pet Sounds!) I’ve flown in instruments before. Sheet, I’ve even added a snare drum to a damaged section of a song that lost the snare. Used my own. Was fun, and a little naughty.

JS: As a guitarist who appreciates vintage instruments, what is Steve Hoffman’s favorite guitar sound and what records have you mastered that have achieved your “breath of life” standard of that sound, when the original-release guitar sound may have been less than optimal due to a label rush job, pressing from a backup master, etc.?

SH: Wow, these questions are amazing. Really giving me a workout. My favorite guitar sound? Hmmm, Stratocaster into a tweed Fender Bassman (Buddy Holly, The Fireballs’ sound*), Gibson humbucker with treble rolled off (“Dark Eyed Woman” by Spirit), a bunch. I like songs where the guitar is so unprocessed that I can tell what the heck it is, James Burton’s Tele in Ricky Nelson’s stuff, Steve Cropper’s Tele and Bassman duo on the Stax/Volt stuff, etc. Too much processing and it doesn’t matter what guitar is even used.

Albums that I have brought out a better guitar sound than the originals? Hmm, hard to say. Buddy Holly, some Beach Boys; in jazz, Barney Kessel in The Poll Winners stuff, Kenny Burrell, Grant Green.

(*note: The Fireballs were a band contracted by Producer Norman Petty during the 1960s to add backing track overdubs to Buddy Holly’s unreleased demos posthumously.)

JS: Are you excited about any current or upcoming projects that you are at liberty to share with Copper readers?

SH: Can’t share, everything is on hold, no one has a clue as to what will be released. It’s sad but that’s life.

JS: What would be the top 10 achievements of your career that you would like to be best remembered for after you decide to retire? The list can include recordings, techniques, or philosophies.

SH: I can’t. It’s too Sophie’s Choice for me…I like to think I’ve spread the word to let recordings sound as natural as possible, even Death Metal, etc. And the importance of [using] a good original source when doing reissues.

And it Feels Just Like...Starting Over

So, as I have written about and stated in numerous articles and interviews, my portal to music was laid down through a 4-inch speaker through a Blaupunkt tabletop radio around February 1963.

I was at home, sick for nearly a month, and it was at that time that I first heard “Hit Radio 77 WABC.”

The DJ’s were Scott Muni, Bruce Morrow, Dan Ingram, Bob “Babaloo” Lewis (doing the overnights) HOA (Herb Oscar Anderson) in morning drive (if there was even such a description back in 1962) and Bob Dayton.

The Top 40 seemed really like a Top 10 played over and over again.

To an 11 year old this seemed like the world’s template for music.

Forget all the other music like jazz, classical, folk…they didn’t register one bit. All that mattered was what I was being fed hour by hour, day by day a relentless succession of the same songs that changed bit by bit as new songs were introduced into the Top 40 playlist and then made it to the Top 10 which then became cemented into my brain. This was one year before the Beatles and all the British Invasion artists and the wall-to-wall hits of Motown took over my world (and millions of others).

I contend that the music that you fall in love with between the ages of 12 and 20 create your taste forever.

I’m not a sociologist nor an anthropologist. It’s just one of those feelings, backed up by others who I have asked about personal musical taste.

This doesn’t mean, by any stretch, that one can’t learn to love new music later in life. What it does, however, speak to is the fact that when you are young, you have the time to invest in the music you love, pretty much unencumbered by all the issues that come into play when you get older. And when you get past 50…well, I mean really who the fu*k really has the time?

Harsh?

Maybe, but with COVID-19 literally stopping the world, I have a lot of time on my hands and that has led me to look at my record collection and ask myself why I haven’t listened to 75 percent of the albums I’ve owned. Sure, I might have listened to many of them a long time ago but because I’m in the business, I get albums given to me that just sit on shelves taking up space and looking cool…I guess.

Anyway, I don’t need to listen to a lot of the rock albums that I have because, frankly, I know enough about the artist to either have given some of it a passing listen, or I just disregard the music completely because I know where the artist is coming from and if they didn’t resonate enough in the world to make me care then I just don’t.

There is, however, another issue and that is: maybe there is a musical genre that I really don’t know about and now may be the time to try to get into it.

And that leads me to this latest musing.

I have lots of jazz albums that were given to me when I was an active artist at Atlantic Records. Atlantic Records was founded in 1947 by Ahmet Ertegun, the son of Turkish diplomats who came to the US, and by Herb Abramson.

Atlantic became one of jazz music’s most important labels before moving into R&B, soul and then rock.

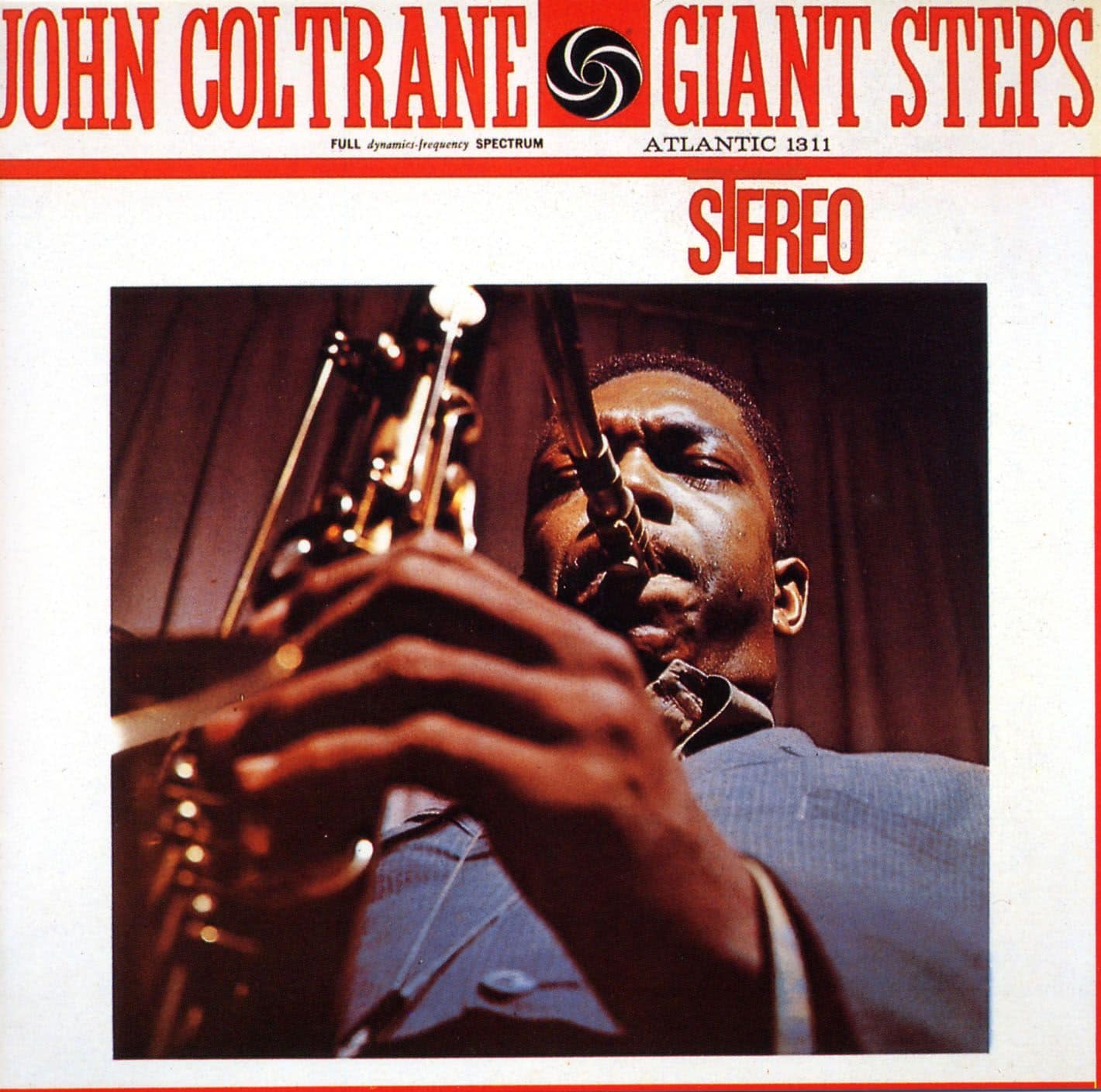

Their jazz roster contains luminaries such as Ray Charles (whose brilliant style also covered not only jazz but pop, R&B and country), John Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, Milt Jackson, Ornette Coleman, Bill Evans and many, many more.

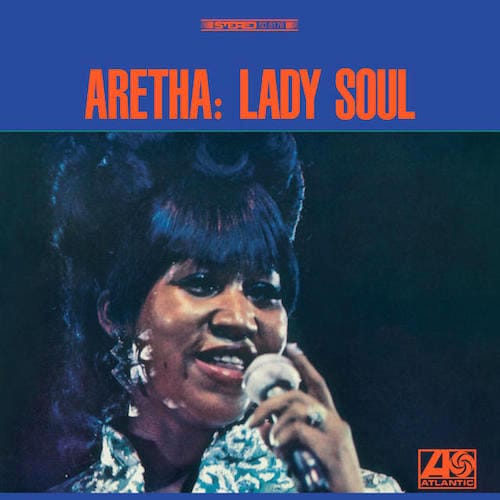

Aretha Franklin created her most famous songs under the Atlantic label.

The point is, that I was on this label beginning in 1983 [with Twisted Sister – Ed.] and I can tell you that I never listened to any of these jazz artists. Ever. Not once. It never registered as something that I would even care about.

One day, in 1990, Ahmet Ertegun gave me copies of most of the albums he and his brother produced during their amazing jazz years from the late 1940s through the early 1960s. In other words, I have a great collection of some of the most revered jazz ever recorded and, over the last 30 years, it has all just been sitting, unopened and unplayed, on a shelf.

Maybe now is the time to find out what I have been missing.

Now, here is where it gets a little more interesting. When I was 17, most of my peers who were musicians were starting to get into people like Miles Davis and Sun Ra. One of my closest friends took me to see Elvin Jones one night at the Half Note in NYC. I began to wonder why I wasn’t (as a musician) following this path. At the time, I was a Deadhead. Putting aside any Dead jokes, the Grateful Dead were as close to a jazz improv band as rock would get and I “got it” totally. I completely understood their musical language.

I used to tell this to my friends but strangely, I was a Deadhead all by myself. None of my musician friends, some of whom were really incredible musicians, liked the Dead. In fact, they hated them and thought that their playing just plain sucked. I just came to this realization because of a conversation I recently had with Mark Pinkus, the US president of Rhino/WMG, which is my current record label as well as the label that oversees the Grateful Dead catalog. I’m older than Mark and when I told him about all the Dead shows I saw between 1969 and 1972, he was blown away. Especially because I walked away from the Dead completely in 1972, and went out of my way to never listen to another Dead song again (if I could help it, but that is another story for another time). Mark couldn’t believe that none of my serious music friends in the 1960s, in New York City no less, were Dead fans…trust me, the only person I ever convinced to go see the Dead with me was my mom. I took her to one of the Felt Forum shows in 1971 and even smoked a joint with her!

The point is that he was shocked that I had no friends who liked them back then. The Grateful Dead may have been the closest to “jazz improv” as I ever got and the point is…I got it…but I didn’t “get” jazz. Not Miles. Not Coltrane, not Bird.

None of it but…I have all these albums and now, I’m living during COVID-19 and I am listening.

All the time.

I put on an album and I just let it play. I’m trying to “normalize” it so I can understand it. It’s like a foreign language. The younger you are when you learn it, the easier it is to understand it. But maybe you can still teach an old dog new tricks.

I’m giving it my best shot and I will let you know how this experiment in new music appreciation develops.

Stay tuned.