Previous installments covered the earlier history of Neumann lathes.

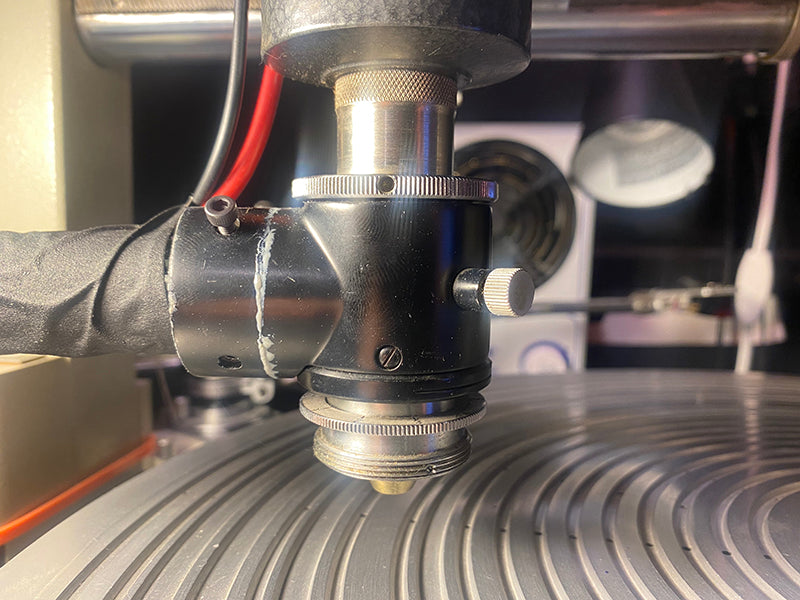

Neumann record-cutting lathes came with a groove inspection microscope, which slid across the platter on a monorail guide with a rack and pinion arrangement, controlled by means of a large knurled knob on top of the microscope. The microscope itself was manufactured by Leitz, which was also known for manufacturing Leica photographic cameras, the Focomat series of photographic enlargers for darkroom printing, a wide range of exceptional-quality lenses (for cameras, enlargers, projectors and various other applications), and of course, all types of microscopes. Their groove inspection microscopes featured through-the-lens internal illumination, to do away with the awkward placement of heat-emitting light sources in uncomfortable proximity to the heat-sensitive lacquer master disks. Interestingly, some years ago, I managed to acquire a very rare and old Lorch precision lathe, which had been used for many decades at the Leitz factory in Wetzlar, Germany, and had probably played a major role in manufacturing parts for the groove inspection microscopes used on Neumann disk recording lathes, judging from the setup of the Lorch and the specialized tooling that came with it!

The illumination system to the side of the objective lens on the Leitz groove inspection microscope.

The platter itself, a true example of German overcomplicated engineering, was a combination of several machined castings, weighing a total of over 100 pounds! The top part, containing the vacuum ports to clamp the lacquer disks down via suction, rested on three leveling adjusters, which were intended to eliminate vertical runout. Through careful adjustment, it was possible to achieve a TIR (total indicator runout) of 0.000078″ (0,002 mm), measured on the outer diameter of the 16-inch platter!

The microscope arm, bolted to the platter end of the Neumann lathe bed, carries the slide rail on which the groove inspection microscope can travel.

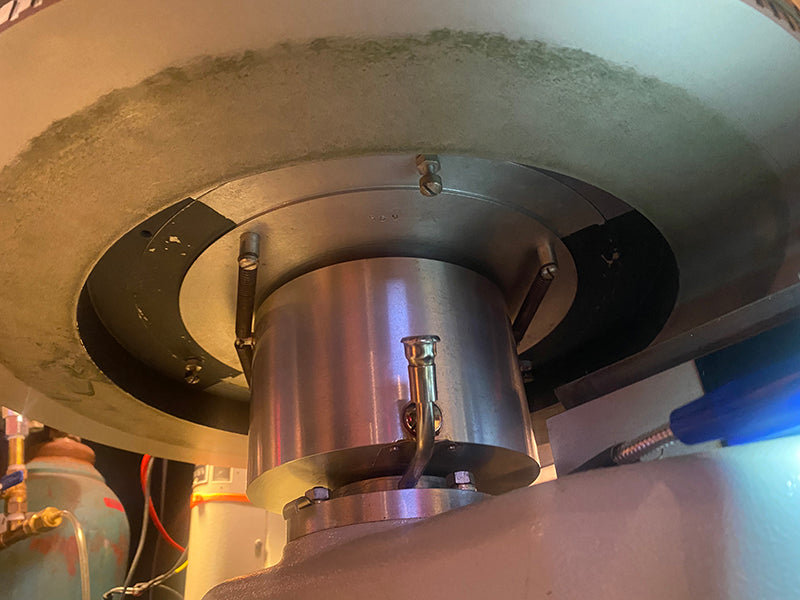

The oil coupler under the platter isolated the relatively noisy Lyrec motor from the platter, ensuring a very low amount of rumble.

The Neumann oil-coupler on a VMS-70 lathe, decoupling the vacuum platter from the Lyrec SM-8 motor.

This was a development that built upon the early Western Electric Kingsbury bearing oil coupler, seen on their early lathes and known as the Western Electric Type RA1388 drive. The idea is kind of similar to how an automatic transmission works in a car. There is no direct mechanical connection between the input shaft (connected to the engine in a car or to the electric motor on a lathe) and the output shaft (in a gross oversimplification, connected to the driveshaft that transmits motion to the wheels in a car, or to the platter on a lathe). The rotary motion, and most importantly, torque, is transmitted through a fluid coupling. It is only the fluid that connects the two shafts, acting upon an impeller. This fluid is automatic transmission fluid (ATF) in motor vehicles and industrial mineral oil on the Neumann lathe oil coupler.

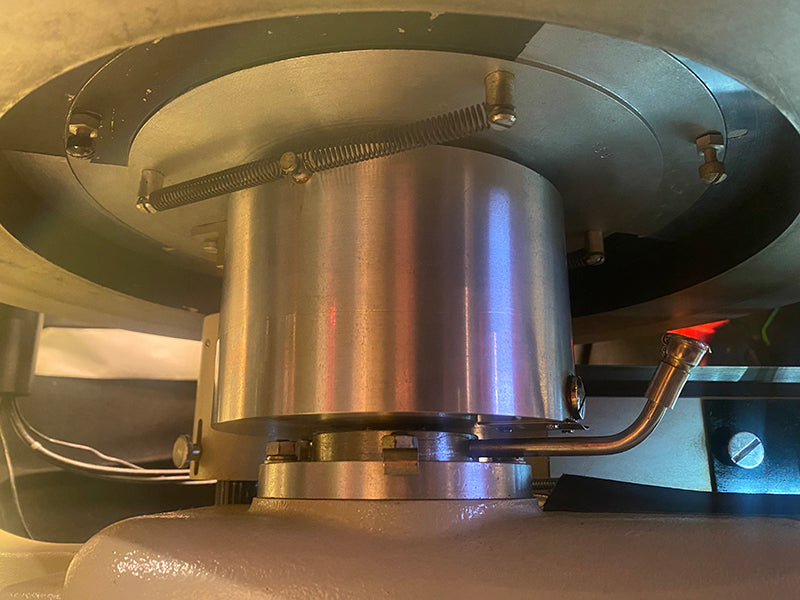

Neumann VMS-70 oil coupler.

But, this is where the similarity ends, as the oil couplers found on lathes and automotive transmissions are very differently designed, since they need to deal with vastly different operating conditions, speed ranges and accuracy specifications. Modern automatic transmissions also feature a torque converter with a lock-up function, which mechanically locks the input and output shafts together at cruising speeds, no longer relying on the fluid to transmit torque and thereby eliminating slip and increasing efficiency. Neumann, unlike Western Electric, also used a spring-loaded mechanical lock-up system, to improve upon the amount of time it would have otherwise taken for the fluid to spin the massively heavy platter up to speed and to reduce any possibility for transient speed errors in the system.

Neumann VMS-70 oil coupler.

The platter motor was the Lyrec SM-8, manufactured by the company in Denmark. This was a floorstanding beast, intended for direct-drive applications. However, unlike the Technics SP-10 and the EMT 950 direct-drive turntables popular in audiophile circles, the Lyrec motor did not use any motor control electronics! It was a synchronous AC motor, which locked its speed onto the frequency of the AC power used to drive it. For those of you familiar with the operation of synchronous AC motors, yes, it did have the massive number of poles needed to spin at 33-1/3, 45 and 78 rpm, and of course there were different versions made for 50 Hz (Europe) and 60 Hz operation (North America and Japan).

The Lyrec SM-8 direct-drive synchronous AC motor, driving the platter on a Neumann VMS-70 lathe.

The different speeds were achieved by essentially stacking three different motors on top of each other! Each motor had the correct number of poles machined for each platter speed, so an SM-8 essentially contained three synchronous rotors and three synchronous stators, one on top of the other. These synchronous motors were, however, not self-starting! To initiate the starting, a separate induction motor was used, on top of the three synchronous motors! Each SM-8 therefore consisted of no less than four different motors, sharing a common shaft. Just when you thought the German engineering community was intense!

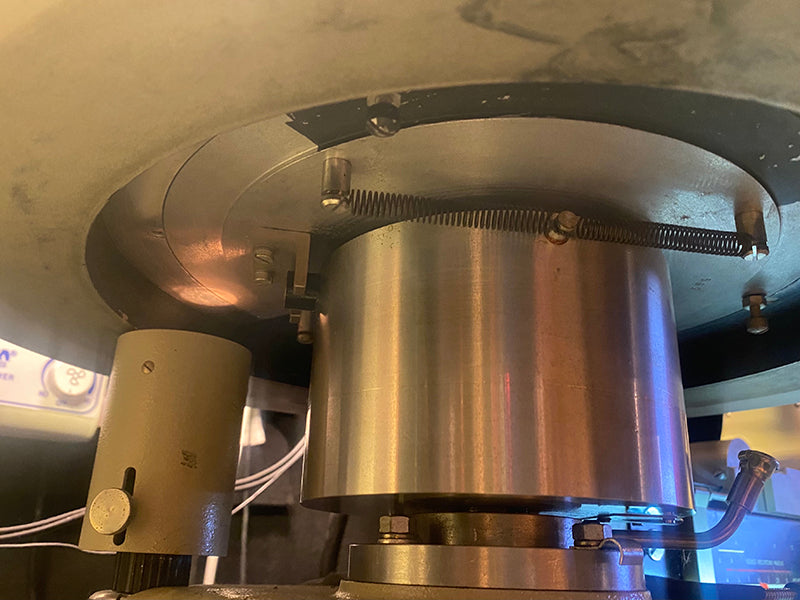

The coupler connecting the Lyrec SM-8 motor to the driveshaft that goes up to the oil coupler, on a Neumann VMS-70 disk mastering lathe.

The cost of these Lyrec motors was also about as intense as you would expect it to be for such a level of complexity. For each frequency version, there were single-phase and three-phase variants. The single-phase types relied on capacitors to accomplish the (electrical) phase shift needed to run the motor. The three-phase types did not need capacitors, and are very rarely seen nowadays. As would be expected, the torque pulses of the three-phase versions were of lower amplitude but at a higher frequency.

The driveshaft coupler at the underside of the Neumann VMS-70 lathe bed.

The speed stability and rumble performance of the entire system was excellent, but soon after the introduction of the Neumann VMS-70 lathe, aftermarket drive systems began to emerge to replace the Lyrec motor, which had already been used on earlier Neumann models and considered by some to be somewhat out of fashion.

One of these systems was the Technics SP-02, similar in many ways to the Technics SP-10 drive system (an electronically-controlled phase-locked-loop system), but bigger and designed to directly bolt on to the Neumann lathe bed, where the oil-coupler would normally go, with a flange on top, which would directly accept the original Neumann 16-inch vacuum platter. The electronics were housed in a separate 19-inch rack enclosure. Very few of these were ever made.

A similar aftermarket system was marketed by Denon. The cost was astronomical, so these were not exactly popular. Nowadays, if you can find one, even the combined GDP of a few small countries wouldn’t be enough to pay for it. The Lyrec SM-8, which was built like a tank and was simple enough to not have electronics that would expire long before the mechanical parts (as was the case with many electronic speed control systems), still remains the most common drive system for a Neumann lathe.

The Neumann SX-74 was introduced in 1974 as the cutter head of choice for the VMS-70 system. It was an upgrade of the very similar SX-68, a stereophonic feedback cutter head employing the 45/45 system, as used by Westrex for their stereophonic cutter heads. The origins of the design date back to Alan Dower Blumlein, who had invented this configuration a few decades too early. The world wasn’t ready for it at the time, so it did not find any commercial application until Westrex revived it in 1958. The SX-74 featured square-cross-section aluminum coil wire for improved coil packing efficiency and low mass, as well as high-temperature materials that could withstand temperatures in excess of 200°C.

The cutter head and the associated electronics will be examined in greater detail in the next episode.

Previous installments appeared in Issues 158, 157, 156, 155, 154, 153, 152, and 151.

Header image: the Leitz groove inspection microscope on a Neumann VMS-70 disk mastering lathe.

All photos courtesy of Greg Reierson, Rare Form Mastering, Minneapolis, Minnesota.