Loading...

Issue 22

DPT: Three Critical Steps To Maximize Musical Engagement

It was about 7 years ago. I was voicing a system to his room for a Get Better Sound owner. Not sure if I had started calling these sessions RoomPlay yet.

Anyway, he had seen & heard me voice his system and liked the results very much. Later that evening, he asked me to identify the steps that he had just witnessed. Amazingly, though I knew exactly the desired outcomes for which I was voicing, I had never thought of discussing a description of them with anyone. Nor had I even assigned a name for them for myself!

Sheesh!!! This was after something like 700 systems I had successfully voiced to rooms!

But as I thought about it, I realized that it was actually fairly simple to come up with a descriptor/name (though not so simple to achieve the results in practice). I finally explained to him that I have always voiced for Dynamics, Presence, & Tone (these days, I often say DPT).

Dynamics

Composers & musicians employ dynamic contrasts in music. Why? To get your attention musically. To make an emotional point.

For our topic concerning Dynamics, we will consider the most obvious offender – the boundary dependent bass region (say from 25-250 Hz).

We will consider Dynamics in the room to be built on achieving the best bass performance. Of course room reflections and other concepts can affect dynamics, but getting the bass as best as it can be will always produce the biggest impact, not so much because bass note irregularities are annoying, but because these colorations have a major impact on musical dynamics…

Therefore, For our purposes regarding Dynamics, “best bass” is not the deepest, but the smoothest. We want to minimize peaks (which mask the true difference in recorded dynamics) and bass suck-outs (which minimize the true difference in recorded dynamics).

(Edited excerpt from Copper Issue 15) “Dynamics are essential in order to have the music “pluck your heartstrings”. That’s why the current overuse of compression (of dynamics) in recordings is so damaging – but hey, that’s another topic…

Here, we are discussing the effects of bass peaks and dips in your playback system. The peaks destroy dynamic range as they were never intended to be there. They mask musical dynamic subtleties in the recording that are meant by the musician to be heard, but you can’t fully experience them, as they are overshadowed by the excessive bass (often referred to as boomy bass).

The same lack of dynamics is true (but for a different reason) whenever there are dips in the bass frequency response. These dips detract from the music’s intended impact and definitely diminish its intended dynamics, and sadly, sometimes in a major fashion.

I have heard too many systems that – depending on the frequency – were almost missing some bass notes, while other notes were booming away. Both bass anomalies detract from the music’s dynamic contrasts, with a potentially far greater effect than those that may occur elsewhere in the midrange and treble.

Please understand that we are not considering uneven speaker response. We are concentrating on the room resonances that all rooms have, based on the room’s dimensions. Peaks in bass frequency response are additive resonances and dips are subtractive.

Of course, various components have varying dynamic capabilities. But this is not about evaluating components – it’s about transforming the musical effects of the components that you have now.

Since all rooms suffer from these issues, how can we overcome them? While some may wish to immediately employ electronic EQ and Room Correction (another upcoming topic in this series), I have found that it’s always best to first smooth out the bass response in an organic fashion (meaning working with the room rather than against it), rather than immediately resorting to using electronic EQ and/or Room Correction.

In a recent issue of Copper (#17), I discussed Dynamics & listening position to achieve the smoothest bass.

Presence

Presence is the next critical issue after Dynamics have been addressed (IMO).

I will say that many audiophiles set up their systems for pinpoint imaging. Honestly speaking I don’t follow that thinking or that path. In my experience, when it is followed as the ultimate goal, it negatively affects Presence & Tone. However, if an audiophile especially values the “audiophile sound effects” capability of his/her system, pinpoint imaging is the better way to go.

When I am voicing for Presence & Tone, and it is finally as good as I can get it, the result is always dramatically more musical satisfaction. In fact, I only stop when I finally realize that I am falling into the music while listening to songs from my voicing playlist that I have heard thousands of times!

Why would we devote valuable resources to improving our audio systems, only to get a result that diminishes the effort? I have witnessed this event occur in thousands of systems over the years, almost without fail, unless an “intervention” occurs. What are the culprits, and how can they be replaced with a musically engaging outcome?

Our reference needs resetting.

Whichever component or system that can produce a ‘bigger soundstage’, or more ‘precise imaging’, or ‘darker backgrounds’, or more ‘bass slam’, or more ‘crystalline treble’, or more ‘air’, greater ‘inner detail’ (such as cash registers ringing in live clubs, chairs creaking, performers breathing, or a combination of several of these sorts of sonic artifacts), etc., it becomes the new reference. But once the audiophile has experienced these sound effects for a while, then it’s off to see if another component or system can do it better.

By the way, I am not criticizing those who follow this path. Indeed, there are similar paths in other avocations. For example, I have known photography hobbyists who owned lots of expensive camera bodies and lenses, but they had no real collection of interesting photos.

For our audio-related purposes, I want to suggest a path that might ultimately be more musically rewarding…

We will identify three main types of Presence. Of course, the actual types of Presence could be infinite in number, but when we get these three effectually operating, the effect of listening to music being performed in your room is powerful, intellectually and emotionally.

Although I teach/demonstrate this critical factor in RoomPlay Reference sessions here in Atlanta, as well as voice for Presence on RoomPlay voicing sessions, I admit to incorrectly assuming that everyone knows about it. I should know better, since no system that I have ever voiced reproduced this aspect correctly on initial evaluation.

Really, properly reproduced Presence is continuous and there are no definite types. But in an attempt to simplify it, I break them down into three types – Concert Hall, Recital, and Intimate. When I believe that these three are working, the final listening test I perform to check my results requires that I have nailed the set-up, as a famous performer will move through several Presence types during the recording, and at all times it should seem uncanningly real, as if the performer is literally slowly stepping back some distance and finally turning his head as he sings, looking at the famous female singer as she is about to sing. In other words, the room has transformed into the concert hall – and in an utterly believable manner.

Concert Hall Presence can briefly be described as the eery feeling that vocals or instruments are arrayed at the front end of the room, well behind the speakers. No sound of any kind should appear to emanate from the speakers. It should sound very much alive. Very Present in the room, though distant, as if we have been transported to the hall.

Recital Presence presents the performers on a stage or in an area behind the speakers, but always much closer. It also delineates between the relative positions of the performers, again sounding very much alive and Present. I use the term Recital because it feels as if I’m sitting in a Recital Hall, enjoying a wonderful musical performance.

Intimate Presence is when a vocalist/ performer appears between – and sometimes even slightly ahead – of the speaker plane. It’s as if they have packed up their gear to come over and perform in your room. They are IN your room. The effect is almost unnerving as it definitely sounds as if they are alive and performing between your speakers. This effect is primarily due to the mic placement that the recording engineer has employed.

As I mentioned above, when I evaluate a system, the ultimate test of properly reproduced Presence in a room is the recording I mentioned above, where the vocalist moves around as he sings, and walks through several layers of Presence as he does so.

When Presence is reproduced correctly, the resulting sound is musically engaging in a powerful manner. If that is what you want to achieve, read on…

Presence has different meanings for people, musicians especially. So we need to understand what I mean when I use the term here. For me, there are three primary aspects of Presence.

First, Presence in a music playback system is the uncanny feeling that either the musicians have packed up their gear to come play at my house, or else I have somehow transported into their performing venue.

When you encounter this sensation, it transforms your attention to the performance. The loudspeakers are gone, and you are in the midst of this palpable performance.

Second, the music has an ease, an effortlessness, a live quality. In other words, the music itself escapes the confines of a sound system or a room and it is simply suspended in time and space in front of you. This is not the same as soundstaging, but the two concepts are related, in that when you get the presence nailed, the soundstaging comes along as a bonus.

Third, there’s a palpability to the music, and this effect is related to what some audiophiles call focus. In this case, it’s the illusion of being able to reach out and touch the musicians and their instruments.

Increased Presence is most commonly achieved by bringing the speakers further into the room. If there are room aesthetics to be considered, locate & record the optimum speaker location, and use that when you want to experience what you paid for. And by all means, put them back in place when you are done! 🙂

Tone

This effect is perhaps more subjective than Presence. But it is nonetheless vital to get right – for your musical enjoyment.

Some people refer to Tone as the general atmosphere of the recording venue, or even the mood of the musical performance. In our case, Tone is mainly about the timbre of instruments and voices.

I have long thought that Tone can just about carry the entire aspect of musical engagement. When Dynamics and Presence have been addressed, adding great Tone to the mix is a fantastic recipe for breaking through those sound barriers that we have all erected from time to time.

Tone usually describes a certain sound or frequency, pitch, or timbre; venue atmosphere; or even the mood and attitude of a person who is speaking, singing, or playing music. All of these aspects—and more—are combined in the tone we want to achieve with our music systems.

For me, great Tone is exemplified by instruments and voices that have that natural weight and richness that we hear live.

Why do we care about it?

Tone seems to be one of the biggest instigators of emotional response. Unfortunately, most systems I hear are notably deficient in this area. It’s always possible to raise a system’s tone quotient—something well worth doing—but not until you have addressed dynamics and presence.

How do we get it without changing components??

Tone is primarily related to loudspeaker placement, separation, toe-in, and often, some form of elevation or time alignment.

Assuming that you have achieved improved Presence, and without going into way too much detail, Tone can be negatively affected by loudspeaker separation. Too much (often to achieve pinpoint imaging), and the sound thins out, losing tonal richness.

A general rule for separation – depending on the speaker and the room – has shown a good starting point for “Y” to be about 80% of “X”, plus or minus about 5%. For our purposes, “Y” is the distance from the center of the left tweeter to the center of the right tweeter. “X” is the distance from the seated listener’s ear to the tweeter.

If you want a little more Presence & Tone, try bringing the speakers slightly closer together. Listen and make further adjustments to your taste.

Toe-in can make a big impact on Tone – adjust to your taste.

Loudspeaker elevation, listener height, and loudspeaker tilt (where needed – forward or backward) can make a significant effect on Tone. For that matter, certain room treatments are very effective in this area, though I never install them until I pretty much know where the speakers and listening seat will be located.

That’s my intro to DPT. Hope you can use it for greater musical satisfaction!

Next up – The ACK Attack and You– we will begin addressing some of those Audiophile Common Knowledge (ACK) issues that were listed in Issue #12…

You can read Jim’s work at his website. www.getbettersound.com

It's a Lonely World

I didn’t set out to be a hired gun, but it occurred to me pretty quickly that this was the likely path to earning a living — either that or find a great band. We can often lose our way on the road to surviving. I saw the light when, in 1985, I had just recorded 8 tracks of different basses on tracks 73-80 of a song that didn’t need more than 16. But such were the excesses of the 80s. A week or so later I was called to a session with Bob Dylan that was stripped down, free and open-ended. And it suddenly hit me that THIS was what I came to LA for, not the too-many-tracks kind of record. Even so, we don’t always love all the people we work with — and, like everybody else in their fields, musicians can be the worst kind of snobs. I’ve had my moments.

All of which is to say that the meeting of Rosanne Cash and my group of players was a very happy meeting — and for me, the happiest of that period of my life. She comes from a lineage that values song-writing, and by the time we met she had developed a sometimes-conversational way of sharing the seeming intimate details of her inner life with her listener. On the cusp of 50, she made an album of songs of the highest quality, primarily about the loss of her father, but also her step-mother, and, on her actual 50th, her mother.

I’ve written before about Bill Bottrell calling me and sending over Rosanne’s demos the night before we started recording, with a particular admonition to listen to the song “Black Cadillac” and to remember the song she had in mind by a band we really didn’t like, and also to keep in mind a song by a guy who we really liked.

Rosanne flew in from New York about 5 PM on day one — and by the end of the evening, “Black Cadillac” was 90% of the way there. She, Benmont Tench and I hung out upstairs in the kitchen chatting about books and the Fabs while Bill and engineer Mimi Parker finished the set up, and then we gathered around Rose on the floor of the studio as she played the song down. Benmont wrote up a chart, it was copied, and we set to work.

To someone who doesn’t know the process, it can seem very mysterious – even telepathic; some would argue that it is telepathic, but years of work suffice just as well. Someone begins playing and the rest of us just fall in, playing what our instincts have taught us over the years to hear. In my case, at least with the song “Black Cadillac”, I knew that whatever line I came up with, it needed to approximate a shape. I hadn’t rehearsed the song in my own, but knew that it would have a certain kind of vibe, and found that shape while the rest of the guys found what they were going to play. We played the song down a few times and “rolled tape” (I can’t actually remember if tape was used or not, though my instinct says yes — we hadn’t gone tapeless yet). And by take 5 we were all there.

By 90% of the way there, what I mean is that the essential framework of the song, everybody’s parts, the dynamic shape of it, was finished. What I heard in my headphones as we got the take was largely what you hear. A couple of overdubs the next afternoon and that was it for this first round.

I can’t remember just why, but a little while later I punched-in the bridge section (“Now it’s a lonely world; I guess it always was…”) — maybe I had a better idea. Whatever it was, there was a reason for me to do it, but what I remember about it now is only that it was better than the final version. It had a swing to it, a kind of roll, that’s been lost. This version of that part worked.

(By the way, I used a Rick Turner Model 2 bass, and the Versatone/V-72 set-up I described last issue. Why? Who knows? — it just felt right. The bass overdrove all the electronics just perfectly.)

The song got major surgery down the line — it was perceived as a possible hit — but then largely got put back to the way it was. Fortunately, the changes that were tried really didn’t work. When Julian Raymond and Andy Slater first heard a rough mix, they went nuts. What that meant in late 2004 was “gridding”. Gridding is the process of moving everything slightly so that, rather than the free-floating time that the song was played with, it all lines up on a (fairly fine) grid. It’s a way of making the song extremely regular. I had to re-do the bridge section yet again, and this time I played a simple pulse on the tonic of each chord. Although the gridding was undone, the bass part stayed as it was.

Later on somebody — I think it was Julian — complimented me on the bass, saying something like, “You couldn’t have played it any better.” But Bill looked at me and said, quietly, “Oh, yes, you could; you did already.”

Finally, the song got a horn overdub — mariachi-style trumpets doing the “Ring of Fire” line at the climax of the song, swimming in the chaos of the ending.

A few weeks after the album was released, I got a call from Dublin from a friend, a well-known session guitarist. He called to say, “No one could have played that but you.” I doubt it’s true, but it was nice to hear.

All I Want For....

If you could ask for one piece of vintage gear that you once owned and regret getting rid of—get it back again, crisply new and fully functional, neatly wrapped with a bow for Christmas or Hanukkah, what would it be?

Or, to broaden the field, if you could ask for one piece of vintage gear of any kind as a gift to yourself…what would that be?

I’ve owned a lot of vintage gear, most of it bought for almost nothing. It’s not that I’m a particularly good gear-hunter, it’s that I was and am cheap, and I kept my eyes open. Most of the gear was picked up in order to turn it for a profit. Sometimes, a major profit.

Yes, I regret that, and wish I could’ve kept some of the gear. Most of the transactions occurred early in my married years, and we always always always needed more money. Rent, or another piece of gear piled up? The choice was pretty simple.

It’s probably just as well: if I’d been able to keep everything that passed through my hands, you’d probably see me in sweatpants and a dirty Batman t-shirt on an episode of Hoarders. Sheesh.

So: of all the stuff that passed through my hands, what would I want back?

—Thorens TD-124 with Grado tonearm and Ortofon SL-15E cartridge (built-in transformers). The table and arm were a trade-in to a dealer, and I paid $60. The cartridge was a factory rebuild, gathering dust at another dealer. $30, I think. Total investment: $90. Replacement cost now? What, $1500? More? And yes, it would need a better plinth.

–Marantz/JBL console. A lifetime of glancing behind farmhouses as I drive past —ostensibly looking for the lost Dymaxion—has left me with pretty spectacular peripheral vision and a hyper-vigilant set of internal alarms: WAIT! What the hell was that?? As I drove home down Central Avenue in Memphis one day, thirty years or so ago, I noticed a ’50’s-style custom mono console on the front porch of an antique dealer. A champagne gold faceplate caught my eye. Could it be…?

Yep. Console had a Marantz 1 preamp inset in the face, above a crappy Garrard RC-80 changer, and next to a Sherwood (S2000?) tuner, complete with magic eye. Looking in the back, I saw a Marantz 2 power amp bolted down, and a JBL D123 full-range driver. The dealer told me they’d cleared out a houseful of effects, and “had to take it with everything else. I was gonna trash it.” I said, “I’ll give you $15,” brandishing all the cash I had in my wallet. He snagged it out of my hand almost faster than I could see, and said, “get that junk out of here.”

I lugged it home and had in my garage for several years, next to the broken Apogee Stage and nonfunctioning Kloss Novabeam. Unlike those trash-heap refugees, everything in the console worked, and worked well. Fed from the tuner, a cassette deck (the ’80’s!!), or the Thorens, the console produced a sweet and coherent sound that beat almost anything I’d heard up ’til then. Unfortunately, I eventually broke it up and sold the Marantz pieces, the tuner and the D123— I think for over $1000. It’d be worth more today, but not as much as you’d think. Marantz stereo units go for a lot more, and the D123 lives in the shadow of its bigger brother D130—which is a shame, as the ‘123 has a sweeter mid and high end.

-JBL Paragon. Having grown up with House Beautiful and Sunset magazines in the early ’60’s, I was and am a fan of what is now called “mid-century modern” design, as exemplified by Charles Eames, Dieter Rams—and Arnold Wolf, who designed the Paragon, several other spare and elegant JBL models, and the famous ’50’s JBL logo. The Paragon is a landmark design, a massive nine-foot console containing two complete speaker systems, a stereo speaker system in one sculptural sweep of wood (that curved center panel drops into a groove in the two separate speaker cabinets, allowing transport in three pieces; the panel acts as a diffusor for the mid-horns, which bounce their signal off the panel and create a panoramic soundstage).

When I entered audio around 1970, the Paragon was acknowledged as the ultimate speaker system. Unbelievably, it was in production from 1957 to 1983. Mine was a rather worn unit, a trade-in to the same dealer from whom I bought the Thorens. He viewed the Paragon as a white elephant, and I managed to get the price down to $600. I sold it soon afterwards for $1400, never even getting it out of my parents’ carport—so I can’t really say I’m familiar with the sound. Most say the design impresses more than the sound, and that wouldn’t surprise me. Good ones these days start at around $10,000, and rapidly go up to as much as $50k. It would be interesting to be able to play with one and really optimize it.

–Western Electric stuff, lots of it. For a number of years in the ’80’s I pulled Western Electric and Altec gear out of old theaters (I was too stupid to recognize the worth of the old RCA systems, but that’s another story). The most memorable experience was pulling a WE system out of the attic of an old moviehouse converted to a porno theater; I was guided around by the manager, an elderly, chainsmoking woman, while “action” movies ran on the big screen. Like I said: memorable.

That theater yielded a complete speaker system including 4181 woofers and full cabinet, a 555 mid/tweeter with horn (which model, escapes me). I don’t recall if there were amps, but I only paid $200 for everything. I was paid ten times that when I sold, and felt I’d made out like a bandit. These days, even broken 555s sell for $5k and up, and 4181 reproductions sell for $15k. Real ones? I can’t recall the last time I saw one. Through the years the quantity of WE gear I handled would buy a decent house today, and would probably have paid for my son’s college on top of that.

Oh, well.

Oh, there was a lot more cool gear through the years. I’d love to have my Nakamichi Dragons back—both tapedeck and turntable. Other things, not so much: a triamplified Audio Research/Tympani system was unreliable and a constant source of headaches. Its modern equivalent would be fun, though.

Of all the gear I haven’t owned, what would I like to have?

Somehow I’ve never owned the original Quad ESLs (often referred to as ESL 57s, reflecting the year of their initial release). There was a near-miss of a minister’s complete Quad system in the mid- ’70s ($300!!). In recent years, Robin Wyatt of Robyatt Audio has performed very impressive demos with rebuilt Quad ESLs. Despite their reputation, they can provide decent bass, if not of the Master and Commander variety. The clarity and palpability of the sound is as impressive as it always was. Yes, the sweet-spot is narrow. Yes, there are some dynamic limitations. I would likely grow weary of the limitations of the Quads, but it’d be fun to try them.

Next time we’ll look at what vintage audio gear folks would like to have back/have. We’ll hear from a number of folks in the audio biz about their lost loves and dream dates. What would you want? Let me know!

Purer, More Perfect Sound

I have spent a lot of time focusing on the Red Book standard of CD Audio, which calls for 16-bit data at a 44.1kHz sample rate. In doing so, I imagine I have given implicit support to the commonly-held notion that this standard is perfectly adequate for use in high-end audio applications. After all, this is what Sony and Phillips promised us back in 1982: “Pure, Perfect Sound – Forever”. While the ‘forever’ part referred to the actual CD disk itself, the ‘pure, perfect sound’ part was clearly attributed to their new digital audio standard.

But if this really is ‘pure and perfect’ as the promise grandly claims, why, then, do we have all these Hi-Rez audio formats floating around? Why do we need 24-bit formats if 16-bit is pure and perfect? Why all these high sample rates if what’s-his-name’s theory says 44.1kHz is plenty high enough? Why bother with DSD and its phenomenally complicated underpinnings? These are good questions, and need to be addressed.

The argument for the superiority of 24-bit over 16-bit is perhaps the least contentious and best understood aspect. Simply put, every extra bit of bit depth allows us to push the noise floor down by an additional 6dB. So the 8 extra bits offered by a 24-bit format translates to a whopping 48dB reduction in the noise floor. Very roughly speaking, the very best analog electronics, microphones, and magnetic tape, all have a noise floor which is of the order of 20dB above that of 24-bit audio, and 20dB below that of 16-bit audio. In simple terms, this means that 16-bit audio cannot come close to capturing the full dynamic range of the best analog signals you might ask it to encode, but 24-bit audio has it handily covered with plenty of margin in hand.

So, in areas of noise floor and dynamic range, going from 16-bit to 24-bit buys us a great deal of potential benefit at a cost of only 50% in additional file size. I say ‘potential’ benefit, because you do require seriously high quality source material in order to take advantage of those benefits. But if you’re reading this, the chances are you have more than just a passing interest in ‘seriously high quality source material’!

Moving on to the sample rate. There are two immediately obvious benefits to increasing the sample rate. First of all, there is actually a further reduction in the noise floor to be had. Without going into all the ifs and buts, this amounts to an additional 3dB of noise floor reduction for every doubling of the sample rate. However, since moving to 24-bit sampling has bought us all the noise floor reduction we can handle, this aspect of increased sample rate is not really very exciting. The second obvious benefit is more nuanced – the fact that by increasing the sampling rate we can also increase the frequency range that we can capture. This bears examination in more detail.

Suppose we double the sample rate from 44.1kHz to 88.2kHz, and thereby double the Nyquist frequency from 22.05kHz to 44.1kHz. This means we can now capture a range of audio frequencies that extend quite a way above the nominal upper limit of audibility. This is where things start to get contentious. The main issue is that the vast majority of scientific study tends to support the general notion that as human beings we don’t hear any frequencies above 20kHz. Furthermore, that only applies to what Vinny Gambini memorably referred to as “yoots”. Once you get to my age, you’ll be lucky if you can still make it to 15kHz. However, the topic of frequency audibility does throw up some occasional odd results.

For example, in a scientific paper from 2000, Tsutomu Oohashi et al reported that by measuring a number of subjects’ EEG and PET scan responses, they showed that when played Gamelan music (known to be rich in ultrasonic harmonics) their brains did in fact respond to frequencies above 22kHz. The problem is that this paper’s results – referred to as the ‘Hypersonic Effect’ – have not been satisfactorily replicated, and in addition some valid technical criticisms have been made of its methodology. Even the authors themselves showed no apparent interest in following up on their work.

Overall, this, like other arguments of its ilk, doesn’t appear to provide any plausible basis upon which to build a case in favor of high sample rate PCM formats.

Various other studies have looked at ways of assessing whether or not the human ear/brain is capable of resolving sonic effects due to relative timing factors – such as the discernability of time misalignment between signals from spatially displaced speakers (Milind Kunchur, 2007) – and a reasonably consistent picture emerges that we are sensitive to time alignments in the range 1-10μs. This has been argued to imply that our brains are able to process audio signals with a bandwidth approaching 100kHz. This is interesting because it suggests (in a roundabout kind of way) that we may be able to perceive certain effects of hypersonic harmonics of audible frequencies, without necessarily being able to detect those harmonics in isolation (i.e. Oohashi’s idea redux).

Any treatment of timing-related issues opens the door to the discussion of phase, since phase and timing are one and the same thing. A phase error applied to a particular frequency simply means that that frequency is delayed (or advanced) in time. For example, a time delay of 10μs is exactly the same as a phase retard of 0.628 radians for a 10kHz frequency. Interesting things happen when you start to apply different time delays (i.e. different phase errors) to the different individual frequencies within a waveform. What happens is that the frequency response doesn’t change per se, but the shape of the waveform does. So the question arises – are phase errors which change the shape of a waveform, but not its frequency content, audible? It has taken a while, but a consensus seems to be emerging that yes, they are.

The connection between the audibility of phase and the improved fidelity of high sample-rate PCM recording is a slightly tortuous one, but I believe it is very important. Recall that Nyquist/Shannon sampling theory requires the very simple assumption that the signal is band-limited to the Nyquist Frequency. Therefore, in any practical implementation, a signal has to be passed through a low-pass filter before it can be digitally sampled. I’m running short of room in this column, but basically, the lower the sampling rate, the more aggressive this low-pass ‘anti-aliasing’ filter needs to be, because the Nyquist Frequency gets closer and closer to the upper limit of the audio band. With 44.1kHz sampling, the two are very close indeed.

As a pretty good rule of thumb, the more aggressive the filter, the greater the phase (and other) errors it introduces. These errors are at their worst at the frequencies above the top of the audio band where the filter is doing most of its work, but the residual phase errors do leak down into the audio band itself. My contention is that the ‘sound’ of PCM audio – to the extent that it adds a distinct sound signature of its own – is the ‘sound’ of the band-limiting filters that the signal must go through before being digitally encoded. And I attribute a significant element of that ‘sound signature’ – if not the whole ball of wax – to phase errors. By progressively increasing the sample rate, it allows you to use progressively more gentle anti-aliasing filters, whose phase errors may be less and less sonically intrusive.

Interestingly, with DSD, because the sample rate is so high, we can consider it to have effectively a linear phase response across the entire audio band and into the hypersonic range. Indeed, this may well be a significant reason why its adherents prefer its sound over high sample-rate PCM.

I believe that end-to-end (i.e. Mic-to-Speaker) phase linearity is going to be the next major advance in digital audio technology, one which we will see flower during the next decade. In fact, it may be that this is at least one of the precepts behind the nascent MQA technology.

The Sounds of Christmas: Batteries Not Included

I grew up on Ash Drive in suburban Connecticut. When you hit Thanksgiving you started thinking about Christmas. Today they’re running Christmas ads starting just after the 4th of July. In the 60’s nothing to do with Christmas started until after Thanksgiving. And that was okay; each season needs its own time. The first Christmas tingle came when you saw Santa on TV riding down a snowy slope on a Norelco shaver. As silly as it sounds that first one made me tight in the throat every year. Christmas was just the most anticipated, the most magical, and the granddaddy of them all.

We grew up lower middle class, which meant as far as presents there were good years and bad years. Some Christmases we each got one good toy-type present and the balance were clothes we needed anyway. And we knew we were lucky because twice a day all year our parents would compare us to kids in China who got a kernel of rice for Christmas and were glad to have it. Other Christmases Mom and Dad felt in the money and there would be cool stuff. But it never mattered. It never mattered. I don’t remember ever dwelling on a had-to-have present. Except of course, the Johnny Seven O.M.A.

From the time you are 5 yrs old until about 10 you spend a lot of time in the woods planning army campaigns and pulling the legs off frogs. We knew two kids who kept it up until they were 15, but they were different. We all had the usual run of cap pistols, fake tommy guns and even the occasional rifle that shot plastic bullets. But the Johnny Seven was a game changer. If you could score that weapon system you would be invincible.

One of the problems with playing army in the woods went something like this.

“BANG! Bang bang bang, I got you!”

“Did not!” “Did too!” “Did not, I was down behind this tree and your bullets hit the branch there!” “Did not!” “Did too!”

This argument could go on until somebody snuck up and shot you both. We had a rule you could shoot people having an argument. A boys’ rule that I wish in my heart survived to adulthood. However with the introduction of the Johnny Seven into the Denslow Woods theater of war, you couldn’t argue Jack. You were dead.

“BANG! Bang bang bang, I got you!”

“Did not!”

“Did too! I hit you with the Johnny Seven Tommy gun and grenade launcher!”

“Ok, I’ll come quietly. Just don’t hit me with the anti-tank rocket; I have to be home on time for dinner.”

The Johnny Seven was above my dad’s pay grade, same with all the other kids. Thank Heavens. We’d have had to go back to pulling legs off frogs.

In Connecticut you can get snow as early as mid-November, possibly even late October. I have a confession. It could snow in August and I’d break out Bing Crosby’s White Christmas, the one Christmas record we owned, and play it on my portable RCA. The first snow is always the best. The last memory you have in the yard is sweating your ass off pushing that jackal-hearted lawn mower, and now…it’s snowing. There is a blanket of white softly covering everything perfectly. Even the cords on Mom’s clothesline have an even patina of crystals balancing like a billion refugees all trying to cross a rope bridge at once. Christmas is coming. It was time to start playing Der Bingle. I had to keep the volume down though because Mom lost her mind if you were playing that shit before Thanksgiving.

This album was beautifully produced. The first side had all ballads, incense infused renditions of heart-sung requirements like “Silent Night”,” and O Come All Ye Faithful”, beautiful moving religious and secular songs, ending with a hit from WWII, still one of my favorites, “I’ll Be Home For Christmas”. Oh yeah, and Irving Berlin’s ‘White Christmas’. Still the all-time best selling single.

The ‘B’ side featured more earthy traditionals, more upbeat, and done with the wonderful rhythms of the period. The swing-a-licious Andrew Sisters did several cuts including the first of that side, an old cornball. Crosby’s ability to screw around with beats 2 through 4 and still hit the 1 or skip the 1 entirely and phrase the next bar was like watching a lightning bug wondering where he was going to light up again. And yer both surprised.

By the way, you always hear small solos in pop that make you wonder who is that guy. Like the signature lick and guitar solo in Bowie’s “China Girl”. I’d love to know the guy’s name that did that three bar clarinet solo in this Bing Jingle. It’s perfect.

There are so many sounds of this season. The carols and carolers outside Woolworth’s. The bell of the Salvation Army volunteer with the red pot, wishing you a ‘Merry Christmas’ whether you threw anything in the pot or not. Mom yelling at us to all calm down, smiling as she did.

We always put the tree up on Christmas Eve, an old tradition from their generation, which back in the day included live candles on a pine tree that had been dead for a month. Gotta bring that one back. Must’ve been exciting. Like most families we always underestimated the size of our living room, doors and stairs. Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without the sound of my Dad puffing that tree up from the cellar, using strange words disguised as grunts.

The hush of the night outside before Santa came. I guess the hush of winter is the same every night. But the week before Christmas. With the cold you couldn’t feel because something else was happening. A celebration. Even if you grew up in Florida next to a freeway the ambient sound would bow to the sound of the world holding its breath.

I could say I’ve no idea where the magic comes from, but I know darn well where it comes from and it has nothing to do with presents. We all, all of us, celebrate Christmas. The holiday is full of fun, decorations, traditions, egg nog, mince pie, Muppets and angels. You don’t have to have had a happy childhood or even adulthood to get this. If you’re poor, your joy comes in seeing your kids get a great meal and a warm bed on Christmas Eve. And if you’re not poor you share your blessings to give a poor family that meal and a warm bed and you in turn are blessed. That’s just how it works folks.

Ok, that also gets me in the throat. That man could Sing. Truly the King.

I never needed that first snow to love the annual blessed breath of the birth of the Christ. I also don’t need to exercise the words of better men. We feel differently at this time because we are more aware at this time. God Bless those who feel it all year, or at least starting at the 4th of July. Merry Christmas all my dear brothers and sisters.

Shinola Audio

The name Shinola is most familiar as part of a common expression—which I’m sure you know. As often happens over time, the inherent sense of that expression has become lost (as in the case of “you can run, but you can’t hide”—which I’ll rant about another day). Shinola was a shoe and boot polish, launched in 1907. Known for its high shine, it became popular with GIs in the World Wars, and that expression became common usage. Shoe polish versus… see, in that context, the expression makes sense….

Tom Kartsotis founded Fossil watches in 1984, and eventually sold his interest in the company, which had grown to include a number of other brands such as Relic, Skagen Denmark, and Zodiac. In 2011, Kartsotis and his partners in a new company, Bedrock Brands—yes, Kartsotis is a fan of the Flintstones— were scrambling for a name for their proposed new watch company. After that familiar expression appeared during the discussion, the group went on to license the name Shinola. Since then, the company established a Detroit headquarters in an old GM facility, the Alfred A. Taubman Building. In addition to the company’s creative and administrative departments, the headquarters contains a watch-assembly facility with the capacity to produce half a million watches per year, as well as a facility which produces watchbands and an increasing variety of bags and other leather goods.

The company’s flagship retail store nearby in the Cass Corridor contains bicycle-assembly facilities, behind glass, in full view of store customers. Recently, another assembly area appeared behind glass for the Runwell Turntable, the first product of the new Shinola Audio division.

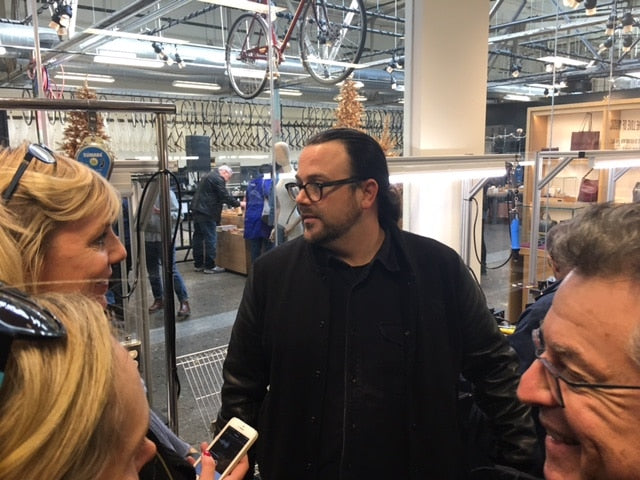

Director of Shinola Audio is Alex Rosson, familiar to audiophiles as founder and former CEO of Audeze (and for the record, it’s AW-deh-zee, like “Odyssey”, not aw-DEEZ). After leaving Audeze, Rosson was approached by Tom Kartsotis, and they discussed the idea of assembling audiophile-quality turntables in Detroit. Two years of cooperation with VPI Industries’ Mat and Harry Weisfeld and metalworking company MDI Manufacturing followed, and the Runwell Turntable was launched in November.

The Runwell has full audiophile cred: massive main bearing and aluminum platter, coupled with belt-drive and a US-made motor; the tonearm is derived from a VPI gimbaled arm. Shinola’s expertise is evident in the sleek industrial design and ease of use: the Runwell’s solid oak plinth and radiused contours evoke vintage turntables from Thorens and Braun, and the modular phono preamplifier and factory-installed Ortofon Blue cartridge make the unit plug-and-play. Future iterations will include a Shinola-made moving-coil cartridge and a variety of preamp options, including a bypass.At $2,500, the Runwell isn’t inexpensive, but nothing about the unit is cheap; construction is massive, performance promises to be excellent, and it’s a thing of beauty.

On November 21st I accompanied a group of journalists from the mainstream media and audio pundits Michael Fremer and Scot Hull on a tour of the Shinola headquarters, including the watch and leather facilities. At the store, Alex Rosson walked us through the turntable assembly area. That evening there was a block party to celebrate the launch of Runwell, including a performance by J Mascis at Jack White’s Third Man Records store nearby. In the back of the Third Man store, we were fortunate to see an amazing recording and mastering studio,as well as a new record-pressing plant, all presently under construction. We couldn’t photograph that area, but believe me, Mikey Fremer nearly plotzed.

News of the Runwell has provoked the usual skepticism and kvetching from audiophile armchair quarterbacks. But: Shinola has the talent and resources to produce attractive, high-performance audio products, and the marketing muscle to sell them to regular people. What’s not to like?

Michael Fremer checking out the Runwell on display in the flagship Detroit store.

Michael Fremer checking out the Runwell on display in the flagship Detroit store.

SET in Carolina

The speakers are Tidal Contriva Diacera-SE speakers, sitting on Symposium platforms. The amps are Chalice Audio “Grail” SET (Single-Ended Triode) mono-blocks.

The amps are 1 of only 2 pair in the world. I am very lucky. Adam Goldfine’s review on Positive Feedback was of the initial prototype and even at that early developmental stage thought they were spectacular. The gentleman behind the amps, Tom Willman, is a genius when it comes to designing amps.

If you are ever in the southern Virginia or northern NC area, stop by!

On the left side of the center is a Lumin A1 Network Music Player with a PSU made for the player by Kenneth Lau. Cables are High Fidelity CT-1UR speaker cables, CT-1UR interconnects, and CT-1 power cords. Currently the amp power cords are Cerious Technologies CT GE ‘blue’ to the amps, and a CPT -300 balanced power cord on the Lumin. The subwoofer is an REL S5.

Would you like Copper to publish your system? Write us by email and tell us what makes it special. We’d love to help you share with the rest of the world.

Berlioz for Christmas

And Liszt for the New Year! Here we go.

Hector Berlioz (1803–69) was no novice by the time he created L’enfance du Christ. Well past the sensational premiere of the Symphonie fantastique and his triumph with the Prix de Rome—something he won only on his fourth try—he began work on L’enfance in 1850, by accident. Arriving at a party at which card-playing was the primary amusement, he gladly accepted his friend Pierre Duc’s suggestion that he spend the evening creating a musical autograph. On the spot, Berlioz began to sketch the now-famous “Shepherds’ Farewell.”

Later that year, casting around for material to fill out a concert program, he decided to present this music as a newly discovered manuscript from an obscure 17th-century French composer, “Pierre Ducré.” The trick worked: everyone praised it. One critic called the music far superior to anything Berlioz himself had written. Eventually he completed an entire segment, “The Holy Family’s Flight into Egypt,” and performed it in Germany as his own work. Enthusiastic supporters encouraged him to create something still more substantial, and so he did. In 1854 the whole triptych (Herod’s Dream, The Flight, and The Arrival at Saïs) was performed in Paris—and acclaimed. Feeling vindicated and creatively reborn, Berlioz decided to try larger projects again, including a monumental setting of Virgil’s Aeneid that would become Les Troyens.

The central narrative of L’enfance seems sadly contemporary: a young Middle Eastern couple flee their homeland when threatened by a murderous tyrant. Arriving in Egypt, Mary, Joseph, and the infant Jesus are denied shelter by natives but finally taken in by a compassionate émigré family “born in Lebanon, in Syria.” Thus, as Berlioz put it in his libretto, “it came to pass that by an unbeliever our Savior was saved.”

I’ve long admired classic recordings of this charming post-Nativity story as led by Charles Munch (RCA, 1956) and by Colin Davis a bit later. Among more recent recorded efforts, that of Robin Ticciati and the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus (Linn CKD 440; 2 SACDs) is a strong contender. Recorded in crystalline high-res sound from live performances, we are placed in front-stall seats that provide every nuance, from the buzzy warmth of the cellos to a delicate flutes-and-harp trio that enlivens part 3. (As a child, Berlioz had mastered both flute and guitar.) Producer-engineer Philip Hobbs strikes a nice balance: you’ll hear the choir rise and sit, but you’ll never feel uncomfortably close to soprano Véronique Gens (Mary) or bass Alastair Miles (Herod/Ishmaelite Father). Here is some of the “Shepherds’ Farewell”:

Ticciati’s performance, while warmly expressive, wisely preserves Berlioz’s calculated naïveté and chamber-music scale. Kudos to Linn also, for a gorgeous 60-page text booklet with musicological notes and a perceptive essay on “Theological Perspective” that ranges much further than “theology.” Let’s hear some of the Ishmaelite flute dance, a moment that Berlioz surely associated with his own childhood:

Or perhaps you would prefer authentic 17th-century French music for the season. Just in time comes a brand-new offering from Sébastien Daucé and Ensemble Correspondances of Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s Pastorale sur la naissance de notre Seigneur Jésus Christ (Harmonia Mundi HMC 902247). I’ve praised Daucé’s work before in this column. He continues to advocate for Charpentier (1643–1704) as the greatest composer of his generation, and when you hear his Ensemble play and sing this, you will see why. Huge chunks of the album are available here; you can also stream the whole thing on Spotify if you have a (free) basic account. Here’s HM’s official trailer:

What else? Well, maybe it’s time for a new (or your first) Symphonie fantastique. The industry keeps turning out new recordings of this old favorite. But there’s a need for the good ones, because this music must be continually refreshed, resuscitated, resurrected at the hands of great interpreters. It depicts the wild emotional flights of a young composer in love. Spontaneity is essential.

Ticciati and his home team, the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, did a nice job for Linn recently. But I am much more taken by Daniel Harding’s new reading with the Swedish Radio SO (those Swedes again! Harmonia Mundi HMC 902244). They pull off this fiery, volatile work with superior dynamic nuance, tempo flexibility and transparency of detail. I heard lines I’d never properly appreciated before. The release is filled out with a dance suite by Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764), and believe it or not, this helps. You’ll find yourself making comparisons that otherwise wouldn’t have surfaced. Check out the fire and finesse in the 2nd-movement waltz (“Un bal”):

And so to Franz Liszt (1811–86). I’ve been reading Ben Ratliff’s book Every Song Ever. He organizes his topic, “twenty ways to listen,” into 20 succinct chapters, each devoted to a single aspect of music, like repetition, slowness, speed. Also, virtuosity.

Music lovers routinely call Liszt a “virtuoso.” He certainly did develop technical skills way beyond those of his peers. But merely elevating one’s technique is not enough. Ratliff, a jazz critic, gets closer to the full-on definition when he writes

Jazz is often entered into by musicians who might feel that their gift is too large to be contained by pop or the church or classical music. . . .

Are the truest virtuosos complete? They seem to want to be, don’t they? They want to surround you and spread their shadow of certainty over the entire history of their form.

It wasn’t enough that Liszt played rings around other pianists; he felt compelled to compose as well, and to invent new genres (e.g., the symphonic poem) as he did so. Furthermore, he supported other composers, commissioning their work, sponsoring performances, preparing piano transcriptions of their symphonies and greatest-hits medleys of their operas (he called them concert paraphrases). By doing all that, Liszt often managed to become the Man of the Hour even on occasions when he was ostensibly not. Whatever he turned his hand to, he turned it grandly.

How to listen to Liszt? Many paths lead to salvation. A while ago I got ahold of Kirill Gerstein’s hi-res recording of the Transcendental Études (Myrios MYR019). His performance was pretty darn good. And the recording quality was superb. I got his Sonata in B Minor, also pretty darn good.

And then I heard Daniil Trifonov play this repertoire. My jaw hit the floor. A veil was lifted. Et cetera. Trifonov’s new DG album, Transcendental, features the Paganini Études, two sets of Concert Études, and of course the Transcendentals.

Let’s compare the first two minutes of each performer’s reading of Transcendental No. 4, “Mazeppa.” Gerstein:

Trifonov:

Trifonov takes slow movements slower and fast movements faster. But that’s the “easy” part, i.e., Romantic Interpretation 101. He also has the horsepower and control needed to whip around corners, dodge, feint, accelerate, and stop on a dime. Which he harnesses in the service of the deep, wild content that Liszt brings to these stories. Barbara Jepson, writing in WSJ, notes Trifonov’s “keen sense of structure.” Exactly. They’re not just technical “studies.” They’re stories.

Here is a little of “Gnomenreigen” (“Gnomes’ Dance”):

And “Un sospiro” (“A Sigh”):

Why do we even call them “études”? Because they pose technical problems for the pianist. The treble melody in “Un sospiro” has to be picked out by alternating left and right hands to play single notes. (Looks flashy in performance, but you can’t see it on a recording.) Live or Memorex, it should sound absolutely seamless. If the pianist is a virtuoso, it will.

Want more? Pianist Leslie Howard has recorded every note of Liszt’s piano music. Howard is no Trifonov, but he’s pretty darn good. Once you’re hooked on Liszt, this could be the way to roll.

It’s guaranteed to keep you busy well into 2017.

Why Do We Do What We Do?

Aside from the fact that it sounds like the chorus of an unreleased Sinatra flop,

I think the title presents an interesting question. Why bother? What is it that drives people to design audio products?

The pat answer is, “we love music”. Well…plenty of people love music without feeling the need to build devices that will recreate it. Are there certain characteristics that drive one to being an audio designer?

I think there are, and I’m going to fumble my way through the ones that are evident to me. Undoubtedly there are others, and I’d be interested in hearing what you think.

1. Love of music, perhaps to the point of obsession. I think that second clause is important: I know plenty of people who “love” music, constantly surround themselves with it, but treat it largely as background noise or a mood elevator. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s not the attitude that really drives one to do something to make the music played sound better, or more lifelike.

For example: my girlfriend Pat always listens to music while she works, and avidly seeks out new music as well as old favorites. But when we listen together, even while driving in a car, our attitudes diverge. I tend to analyze different instrumental or vocal lines, oddities in the recording or performance, the bits and pieces of not just the music, but the recording of it. And, audiophile geek that I am, I tend to talk about those elements.

Pat listens to the music, occasionally bopping along to it. Her frequent response to my commentary is a slightly-testy, “do you ever just LISTEN to the music??” Meaning: not analyze it, not pick it apart, just listen and feel.

Well…no. Or not very often. When I do “just listen”, it’s for emotional recovery, or when I use music the way most people do, as backdrop while working. I nearly always have music playing as I write, but it has to be a very particular type of music: medium- or up-tempo, preferably instrumental. If I play music with vocals, the vocals have to be part of the greater sonic wash, or they distract me.

I can play Radiohead or the XX, for example, and not get sucked into actually listening to the words: the vocals are mostly just sounds. I have no idea of the words to any Radiohead song other than “Creep”. A singer like Sharon van Etten, on the other hand, will eventually distract me, and cause me to listen to what she’s saying in the song. And thanks to Michael Lavorgna for introducing me to that massive time-sink….

But I digress.

2.Be an active listener. I think I’ve just described the difference between a casual listener and an active listener. It’s hard to imagine most casual listeners being driven to do something about the way they hear music reproduced. Many beginning designers are driven to possess better equipment than they have, and build their own simply because they can’t afford ready-made gear. There may also be an attitude of, “huh, I can do better than that”—an attitude shared by many musicians, as well.

3. Not have a life.—I’m kidding here. But the problem with obsessions is that they’re, well, obsessive. Once one begins traveling the path of designing and building gear, there are always new tweaks and techniques to explore, and the more one learns, the more there is the realization of things you don’t know. As Einstein supposedly wrote, “as a sphere of light expands, so, too, expands the sphere of darkness surrounding it.” It’s how veteran designers like Harry Weisfeld, Nelson Pass, and Paul McGowan keep coming up with new techniques to play around with.

4. Be analytical. Learning about the elements of music is both an emotional and intellectual process, and requires an understanding of the variety of building blocks available. That same process is at the basis of all engineering.

Objective? Subjective? Who Cares? Part 2

Part 2: Testing 1, 2, 3.

Forget the stories and debates about “objective testing,” or its failings, that you read about in consumer magazines or hear about on audio internet sites. 99% of those discussions are meaningless, based on equally meaningless tests done too casually by people who are neither unbiased nor true experts; people trying to prove a point, one way or the other. Good objective testing takes time and care, and is used to understand, not advocate. Similarly, real audio science is conducted at research laboratories and universities, not magazines and trade shows. It is done by researchers trained in experimental design and dedicated to the fields of hearing and perception, people who have no stake in any particular outcome, publishing in journals that would be totally obscure to the vast majority of audiophiles.

It is important to recognize that objective testing is not the same as, “meter reading.” Meters may, of course, be involved in specific types of objective audio testing, but their use in modern audio research work is rather limited. Aside from routine, test-bench engineering tasks, the majority of objective tests and experiments include listening panels working with excellent equipment. Good experiments, the ones that other professionals put any stock in, are sincere, carefully designed, low stress and make every effort to be unbiased. They take into consideration the range of individual human hearing capabilities, from limited and naive, to Golden Eared and expert, and they don’t assume the outcome. Generally, these experiments fall into two different categories: experiments which attempt to understand the limits and abilities of hearing (in other words, can we hear some sound or detect some slight sonic difference or not?), and experiments which attempt to understand what people prefer. These are very different matters, each presenting its own unique challenges, and so the kind of experimental protocols used to conduct them also are different.

The first kind of experiment might ask, “What is the highest frequency that is audible to any listener, or which affects the sound in any way.” In contrast, the second kind of experiment might instead ask, “Do listeners prefer amplifiers with response over 20KHz, or not?” These are obviously very different questions, yet such questions are constantly being confused in the popular debate over objective testing. “Can anyone tell the sound of these amps apart?” Type 1. “Which of these amps do most listeners, prefer?” Type 2. “Can people taste any difference between Coke and Pepsi?” Type 1. “Do most people prefer Coke or Pepsi?” Type 2. And, while it is true that preference itself is complex and can not be measured or explained unambiguously, the testing and documenting of preferences can be done objectively.

OK, so what does this objective testing say about the current state of high end audio, once you toss out the dross? Frankly, it says that some of the things that audiophiles have long believed are no longer true, if they ever were. At least a few of the assertions audiophiles often make about the differences in sound between different pieces of gear seem to disappear in even the most careful and sympathetic experiments. Likewise, some people who insist they prefer Coke, actually choose Pepsi. Hey, don’t shoot the messenger, and don’t assume the all the experiments are junk. As I said in Part 1, some of us work very hard to figure out what is really going on, not what one “side” or the other wants to think is really going on.

These days, when it comes to purely electronic components like preamps and amps, the differences between competently designed and properly functioning models are vanishingly small, or even nonexistent. Even the differences between transports and converters are getting to be less than the variations you find between any two speakers with sequential serial numbers. Turntables and cartridges, well, we are still back in the 60’s when it comes to sonic neutrality, for better or worse. I’m intentionally leaving loudspeakers out of this assessment, since we are just beginning to understand how to even think about how they should ideally perform and, therefore, how to test them in a truly meaningful way.

Don’t bother telling me that I am a fool for saying, “All amps sound alike.” Yawn. I am no fool, and that is not what I am saying. No audio engineer has ever seriously claimed that amps in clipping or with excessive output impedances sounded even similar. None that I know of believe that a 8W tube amp exhibiting output transformer distortions sounds like a 100W solid state amp, or that two solid state amps with different damping factors will sound the same into all different speakers. Everyone knows that weird loads affect different circuits in different ways. Everyone knows that it is possible to create artificial, low-level test signals that reveal converter differences—and so on, and so on. There are plenty of good reasons to choose one product over another.

Nevertheless, I repeat what I said: thousands of carefully conducted tests indicate that competently designed electronic components are most often close to indistinguishable when used within their proper operating range, even to the most critical ears. —unless, of course, they are intentionally designed to sound otherwise, as many expensive cables and interconnects are. But that is a coil of worms I will save for another day.

It is very clear to audio scientists that audiophiles and their opinion shapers in the press and in company marketing departments vastly overstate the audible differences between models and brands. And, what you believe is often what you hear. It’s a positive feedback loop that can reinforce the prevailing high end belief system and obscure the facts. So, who in the industry accepts this position?

Having been in this business for approaching forty years, I’ve known a lot of people at a lot of different companies. There are few important reviewers whose home systems I haven’t listened to at length and with whom I have not shared a few too many drinks. I am convinced that most high end reviewers are quite sincere, if not always technically rigorous or correct in all their assertions. It is likewise clear to me that some of the more experienced reviewers have at least an inkling that the emperor is missing some clothes, even as they may dissemble about this and that listening impression.

Manufacturers, however, I don’t consider as quite as kindly. I think many of the design engineers working at high end brands know full well that some of the stuff their marketing department spits out is simply not justified or correct. Indeed, some of those very marketing people themselves probably realize that they are saying things that they could never back up, either in the lab or the listening room. But, such is the game, and it is unlikely to end any time soon. Why should it? What high end brand would gain anything from such an admission? No, it is much easier to convince oneself that there is some esoteric detail about power supply noise or negative feedback or how capacitor dielectrics really work that invalidates all the objective testing results, as if we design engineers and audio scientists have somehow overlooked such things. (We haven’t.)

Of course, this is not a black and white issue. I am well aware that there are many high end beliefs that are absolutely correct. There are even several that science initially disbelieved, but which proved to be true over time. I know this; it is my job to know this. I’ve even taken on the technical establishment from time to time over matters once considered settled and done. Further, as a business person, I totally get it that customer satisfaction is what matters in the end, whatever the reason for that satisfaction. Still, truth matters, too. Customer satisfaction doesn’t change the fact some widely accepted high end beliefs simply contradict what objective testing shows. It is what it is.

Please, try to remember that behind the high end gurus and brand evangelists waxing rhapsodic in magazine interviews and marketing white papers, behind the star designers and the legendary inventors, there are hundreds of skilled engineers working to crank out quality designs month after month, year after year, with little room for error, cost/schedule inefficiency, or under-performance. There are a lot easier and more lucrative ways for an engineer to earn a living than spending the best years of one’s life chasing sonic nuances at the borderlines of human perception in order to sell a few thousand preamps or subwoofers.

By and large, audio design engineers, and audio research scientists, do this because we love music… we love listening to it, we love being around people who create and enjoy it, we love the quest for sonic perfection and we take our sound seriously. Seriously. We want the truth because we sincerely believe that seeking it is the best path to audio perfection. Don’t assume we are always wrong or that the prevailing wisdom is always right. And, when it comes down to just plain listening with your own ears, remember to grudgingly invoke the spirit of Ronald Reagan: “Trust, but verify!”

. We want the truth because we sincerely believe that seeking it is the best path to audio perfection. Don’t assume we are always wrong or that the prevailing wisdom is always right. And, when it comes down to just plain listening with your own ears, remember to grudgingly invoke the spirit of Ronald Reagan: “Trust, but verify!”

Japanese Garden

iPhone 6